Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To describe serum levels of the cytokines IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, as well as polymorphisms in the genes involved in their transcription, and their association with markers of the acute inflammatory response in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.

METHODS:

This was a descriptive, longitudinal study involving 81 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis treated at two referral hospitals. We collected data on sociodemographic variables and evaluated bacteriological conversion at the eighth week of antituberculosis treatment, gene polymorphisms related to the cytokines studied, and serum levels of those cytokines, as well as those of C-reactive protein (CRP). We also determined the ESR and CD4+ counts.

RESULTS:

The median age of the patients was 43 years; 67 patients (82.7%) were male; and 8 patients (9.9%) were infected with HIV. The ESR was highest in the patients with high IFN-γ levels and low IL-10 levels. IFN-γ and TNF-α gene polymorphisms at positions +874 and −238, respectively, showed no correlations with the corresponding cytokine serum levels. Low IL-10 levels were associated with IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592 and −819 (but not −1082). There was a negative association between bacteriological conversion at the eighth week of treatment and CRP levels.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our results suggest that genetic markers and markers of acute inflammatory response are useful in predicting the response to antituberculosis treatment.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Cytokines; Immune system; Polymorphism, single nucleotide

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the most common clinical manifestation of which is pulmonary involvement; however, tuberculosis can affect other anatomical sites (extrapulmonary tuberculosis) or present as disseminated disease.(1)

Despite being a curable disease, tuberculosis remains a major public health problem worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, Brazil ranks 19th among the 22 countries that collectively account for 80% of all cases of tuberculosis worldwide and 108th among those in which the incidence of tuberculosis is highest. According to the Brazilian National Ministry of Health, 71,000 new cases of tuberculosis were added to the Brazilian Case Registry Database in 2010, corresponding to an incidence rate of 37.2/100,000 population.(2)

The systemic inflammation observed in patients with tuberculosis is mediated by the activation of the immune system, with excessive production of cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF- α.(3) After the inflammatory process, there is an increase in the hepatic synthesis and serum levels of acute phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as in the ESR, which have been used in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients, given that their plasma levels directly reflect the intensity of the pathological process.(4)

Genetic factors have been associated with susceptibility to or protection against infection with M. tuberculosis.(5) In the immune response to M. tuberculosis, allele frequencies in cytokine gene polymorphisms vary considerably across populations, as reported in meta-analyses evaluating IFN-γ, IL-10, and TNF-α gene polymorphisms.(6,7) It has been proposed that serum cytokine levels and their role as markers of response to antituberculosis treatment be evaluated.(8) The maintenance of initially low serum levels of IFN-γ or high serum levels of TNF-α and of increased serum levels of IL-17 is associated with a worse prognosis, including a higher mortality rate and lower bacteriological conversion at the end of the 8th week of antituberculosis treatment. Recently, Lago et al.(9) described a possible association between recurrent tuberculosis and maintenance of high serum levels of IL-10 during antituberculosis treatment. The study of the genes involved in these processes and their interactions with the immune and inflammatory responses can aid in identifying better markers of protection against tuberculosis.

There have been few studies simultaneously evaluating the genotypic and phenotypic aspects of the human host immune response to infection with M. tuberculosis.(10,11) Given the paucity of data on the simultaneous evaluation of genetic, immunological, and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, we conducted the present study in order to determine the prevalence of IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592, −819, and −1082; the prevalence of TNF-α gene polymorphisms at position −238; and the prevalence of IFN-γ gene polymorphisms at position +874. The study involved a sample of active pulmonary tuberculosis patients admitted to and treated at either of two referral hospitals in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In addition, we measured the serum levels of the corresponding cytokines and analyzed the acute inflammatory response by determining CRP levels and CD4+ counts, as well as the ESR.

Methods

This was a longitudinal descriptive study involving 81 patients diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and admitted to either of two referral hospitals for the treatment of tuberculosis in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (the Hospital Estadual Santa Maria and the Instituto Estadual de Doenças do Tórax Ary Parreiras), between March 23, 2007 and August 7, 2009. We included patients with positive smear microscopy and culture for mycobacteria, the presence of M. tuberculosis being subsequently confirmed by biochemical tests. We analyzed the following variables: CRP, ESR, CD4+, and bacteriological conversion at the 8th week of antituberculosis treatment.

For DNA extraction, a commercial kit (DNAzol; Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used in accordance with the manufacturer instructions. After DNA extraction, a DNA sample was analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel in order to determine integrity and concentration, the sample being subsequently stored at −20°C.

For the analysis of TNF-α gene polymorphisms at position −238, 100 ng of DNA, 1× buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM dNTP, and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were added to 15 pmol of each primer for polymerase chain reaction, which was performed as follows: one cycle at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 5 cycles at 94°C, 67°C, and 72°C (60 s each), and 25 cycles at 94°C, 62°C, and 72°C (60 s each). For the genotyping of IFN-γ gene polymorphism at position +874, we used 200 mL of dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 8.5% sucrose, 0.25 U of ThermoPrime Plus DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 5 mL of each specific primer, 0.5 mL of internal control primer, and 100 ng of DNA. The mixture was incubated at 95°C for 1 min; subsequently, 10 cycles were performed at 95°C for 15 s, followed by 10 cycles at 62°C for 50 s, 10 cycles at 72°C for 40 s, 20 cycles at 95°C for 20 s, 20 cycles at 56°C for 50 s, and 20 cycles at 72°C for 50 s. For the detection of IL-10 promoter gene polymorphisms at positions −819, −1082, and −592, the following steps were taken: for the −592 position, a 480-bp fragment was amplified and subsequently digested with the enzyme RsaI. For the −1082 and −819 positions, a 360-bp fragment was amplified and subsequently digested with the enzymes BseRI and MslI, respectively. In brief, 100 ng of DNA were added to each polymerase chain reaction, resulting in a final volume of 40 µL (−819 and −1082) or 30 µL (−592), consisting of 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM dNTP, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT, USA) and specific primers for each mutation (10 pmol for the −592 position and 12.5 pmol for the −819/−1082 positions). All mixtures were incubated at 95°C for 10 min and submitted to amplification at 94°C for 30 s, at 60°C for 30 s, at 72°C for 40 s, and at 72°C for 7 min (IL-10 at position −592), followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, at 58°C for 30 s, and at 72°C for 45 s, plus a final cycle at 72°C for 5 min (positions −819 and −1082). The amplified products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 mL/mL).

In the determination of cytokine levels, bead populations were visualized on the basis of their fluorescence intensities. In the cytometric bead array system, cytokine capture beads are mixed with detection antibody conjugated to the fluorochrome phycoerythrin and then incubated with the samples for the "conjugate" assay. The acquisition tubes were prepared with 50 µL of sample, 50 µL of the bead mixture, and 50 µL of detection reagent human Th1/Th2 phycoerythrin. The same procedure was performed in order to obtain the standard curve. The tubes were homogenized and incubated for three hours at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, the reading was performed with a BDTM Cytometric Bead Array system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).(12)

Serum levels of CRP were used as a marker of the acute phase response (APR), i.e., as a marker of the systemic response to severe inflammation. A positive APR was defined as CRP levels > 0.3 mg/dL, whereas a negative APR was defined as CRP levels < 0.3 mg/dL. Serum CRP levels were measured by nephelometry.

The ESR was also used as a marker of the APR, a positive APR being defined as an ESR > 2 mm/h for females and as an ESR > 7 mm/h for males. The ESR was measured by the Westergren method.

We used descriptive statistics, including range (minimum and maximum values), mean, standard deviation, and 95% CI. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in order to test the normality of the variables and the Levene test in order to determine the equality of variances. Variables with non-normal distribution were log-transformed. For means with normal distribution, we used the Student's t-test. We used ANOVA in order to analyze the differences among quantitative variables. We used the chi-square test in order to identify associations among categorical variables. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In the analyses, we used the bacteriological conversion coefficient, which was calculated as the number of cases of patients who converted from a negative test result to a positive test result divided by the total number of patients at the beginning of treatment, and the mutation coefficient for polymorphisms, which was calculated as the number of cases of a given mutation divided by the total number of cases.

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital on April 28, 2005 (Protocol no. 004/05).

Results

The median age of the patients was 43 years (range, 20-60 years). Of the 81 patients studied, 67 (82.7%) were male, 54 (66.7%) were non-White, 8 (9.9%) were co-infected with HIV, 52 (64.2%) reported regular alcohol use, 55 (67.9%) were smokers or former smokers, 20 (24.7%) reported illicit drug use, and 64 (79.0%) had normal CD4+ counts. All patients had smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis.

In the analysis of the prevalence of IFN-γ gene polymorphisms at position +874, of TNF-α gene polymorphisms at position −238, and of IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592, −819, and −1082, the mutant allele frequency was found to be 0.56, 0.56, 0.29, 0.43, and 0.68, respectively.

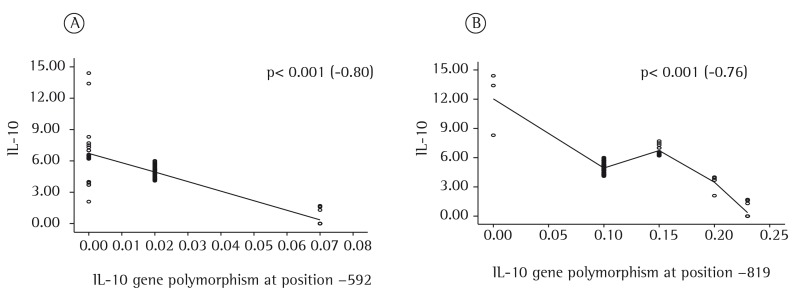

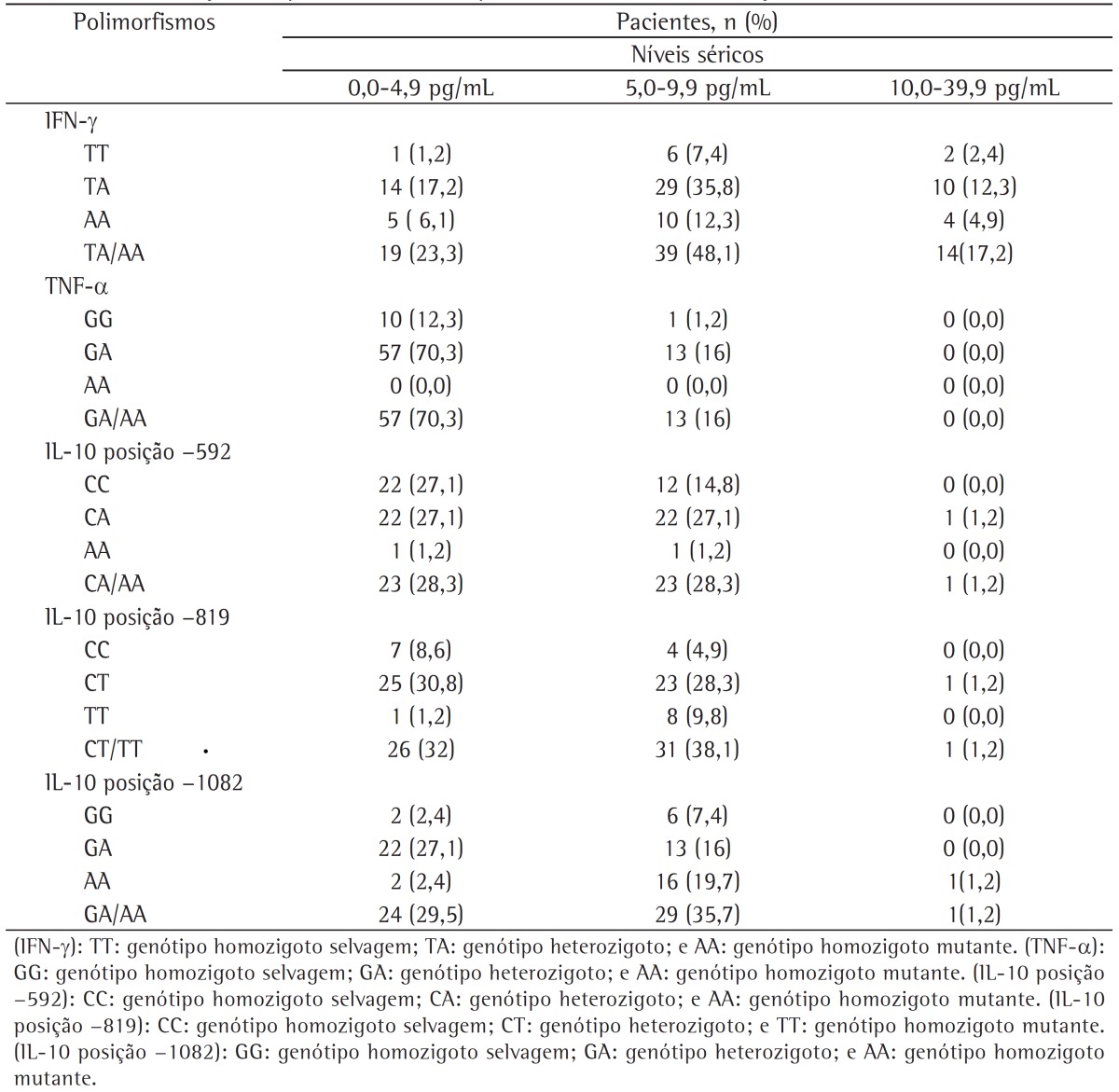

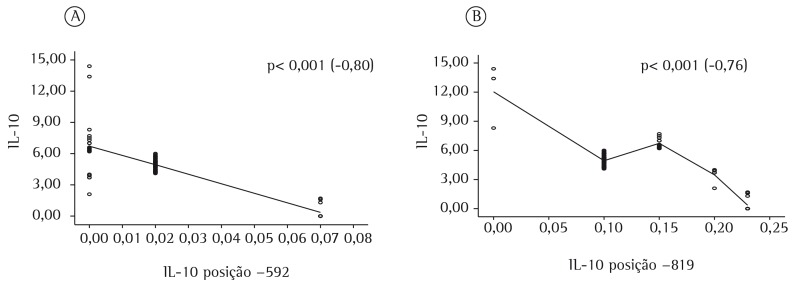

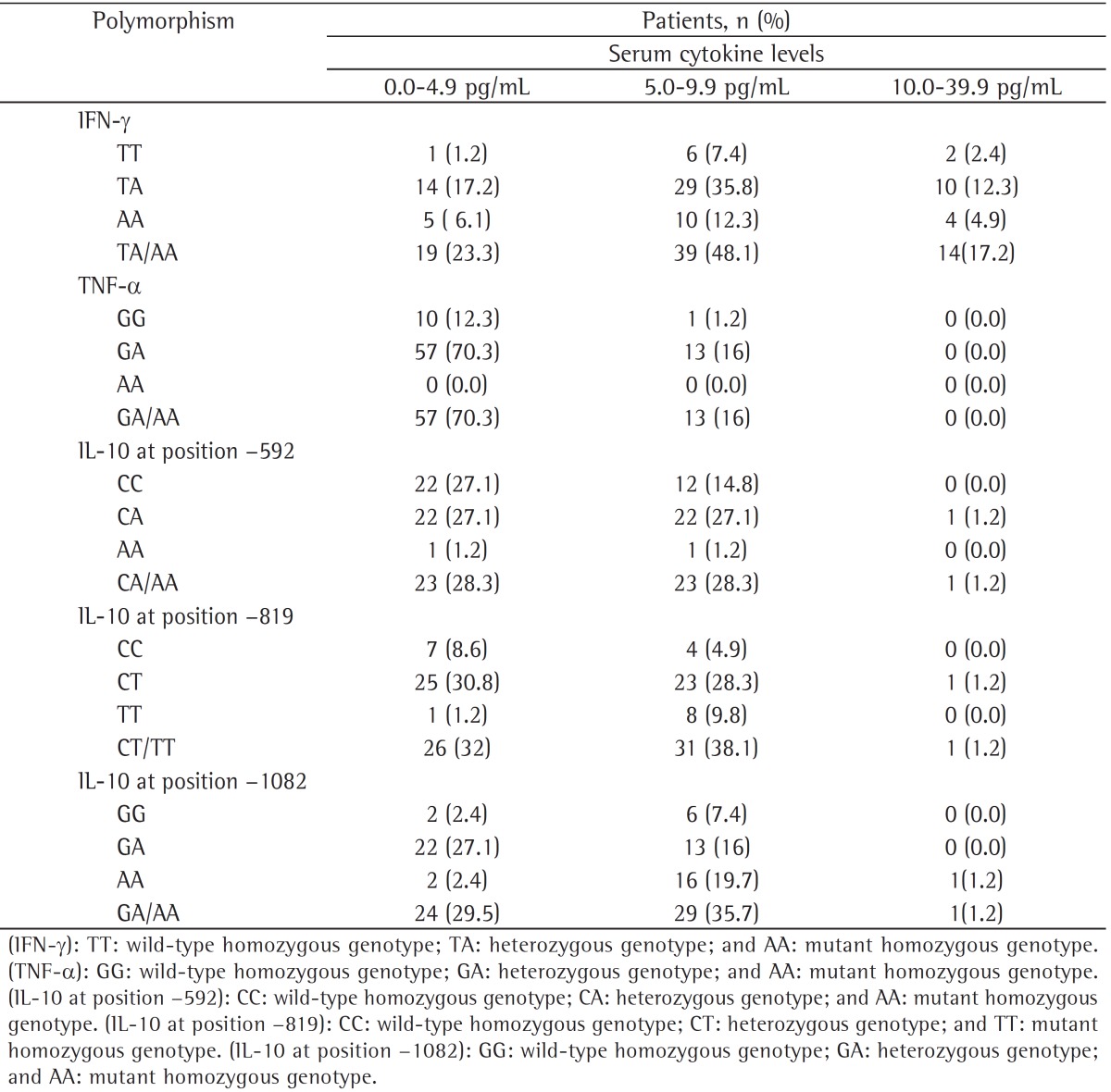

Table 1 shows the distribution of polymorphisms in the patients under study, by serum cytokine levels. Serum IFN-γ levels were found to range from 0 (zero) pg/mL to 20.5 pg/ml, and there was no relationship between low serum levels of IFN-γ and the presence of mutations. Regarding TNF-α, although we found no homozygous mutations, we found a trend toward low serum levels of TNF-α among heterozygotes. We found a negative relationship between serum IL-10 levels and IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592 and −819 (p < 0.001; Figure 1).

Table 1. Distribution of the polymorphisms found in the patients under study, by serum cytokine levels.

Figure 1. Regression coefficient for IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592 (in A) and −819 (in B).

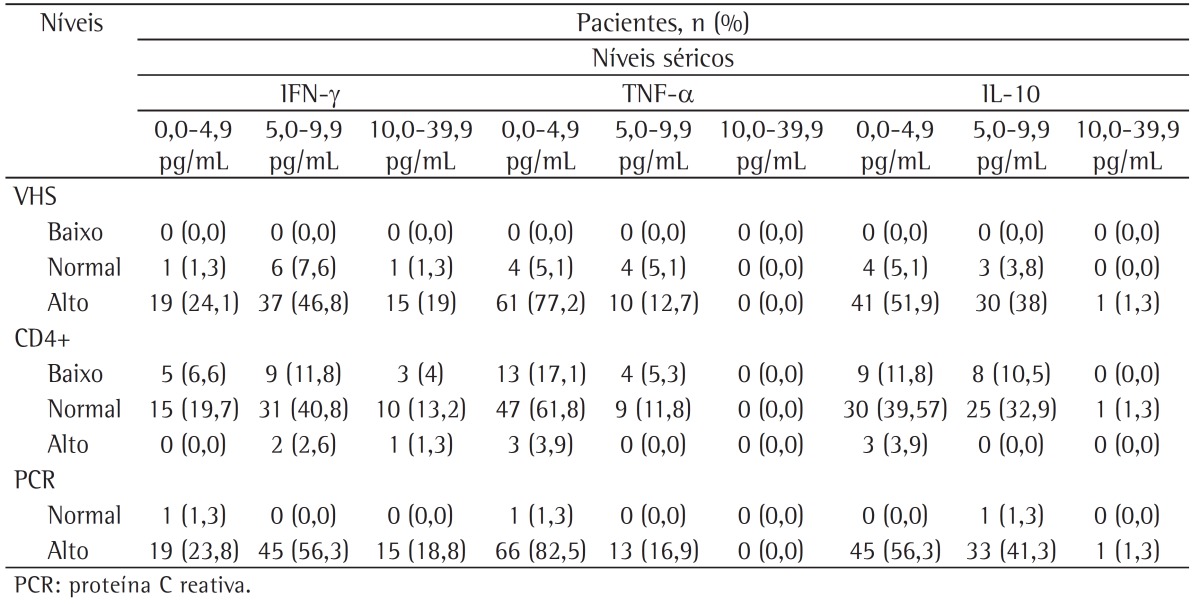

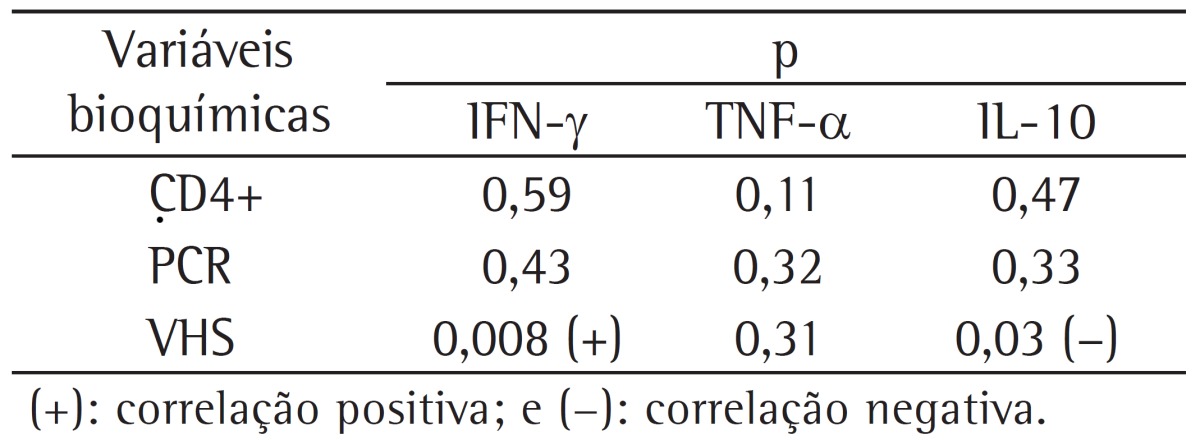

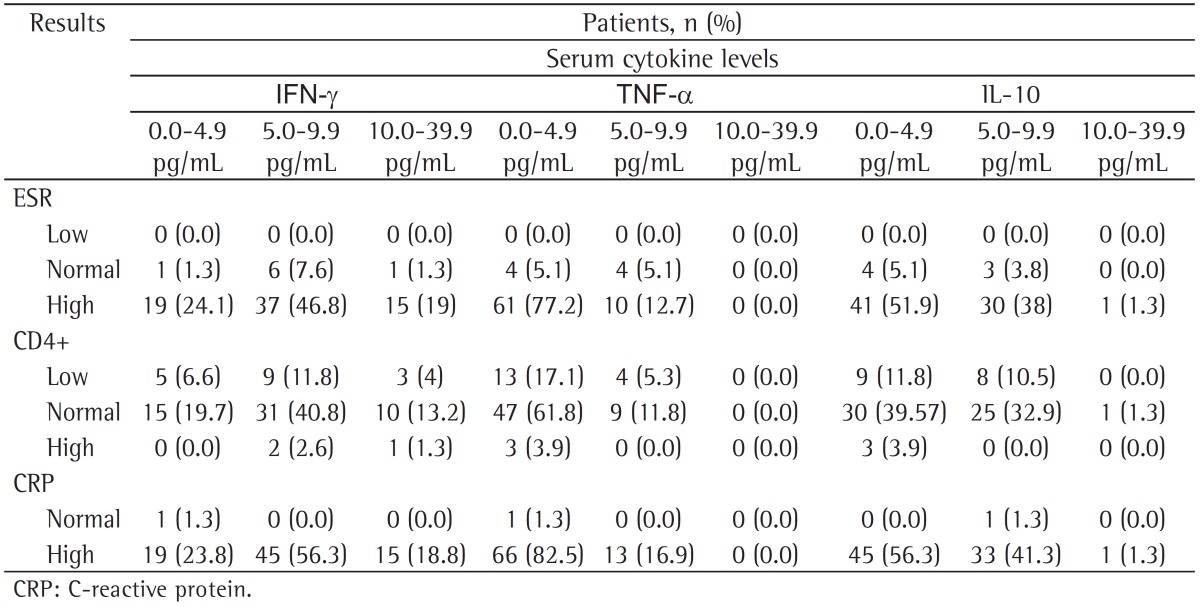

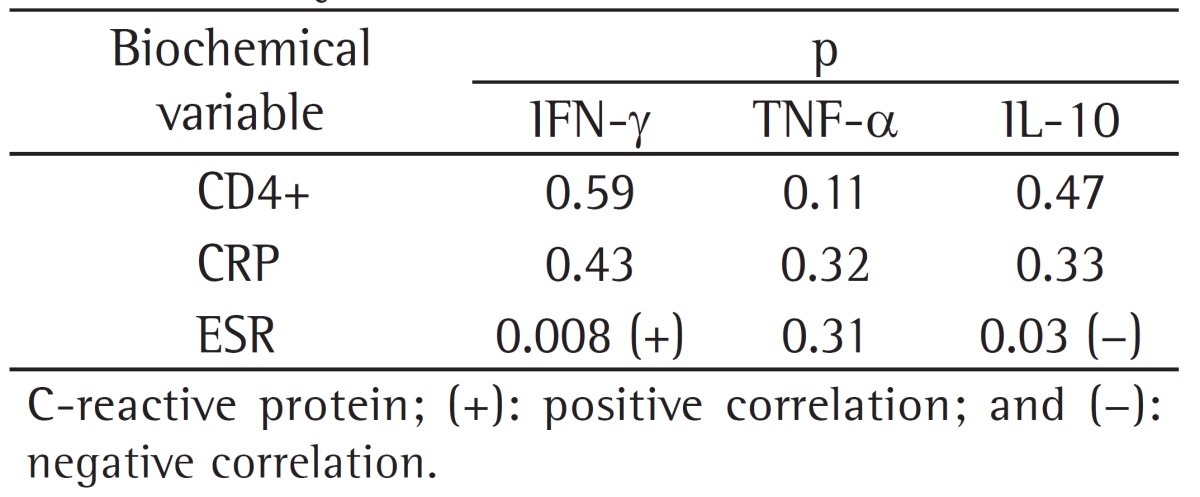

As can be seen in Table 2, there was a trend (p = 0.08) toward lower CRP production in the patients in whom serum IFN-γ levels were low (0.0-4.9 pg/mL) when compared with those in whom serum IFN-γ levels were higher (> 5.0 pg/mL). In the patients in whom serum TNF-α levels were low (0.0-4.9 pg/mL), there was a trend toward a higher ESR (p = 0.04). Low serum levels of IL-10 (i.e., serum IL-10 levels of 0.0-4.9 pg/mL) were not associated with a higher ESR or with higher CRP levels. However, the ESR was negatively correlated with serum IL-10 levels (p = 0.03) and was positively correlated with serum IFN-γ levels (p = 0.008; Table 3).

Table 2. Distribution of serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10 in the patients under study, by laboratory test results.

Table 3. Correlation between serum cytokine levels and laboratory test results.

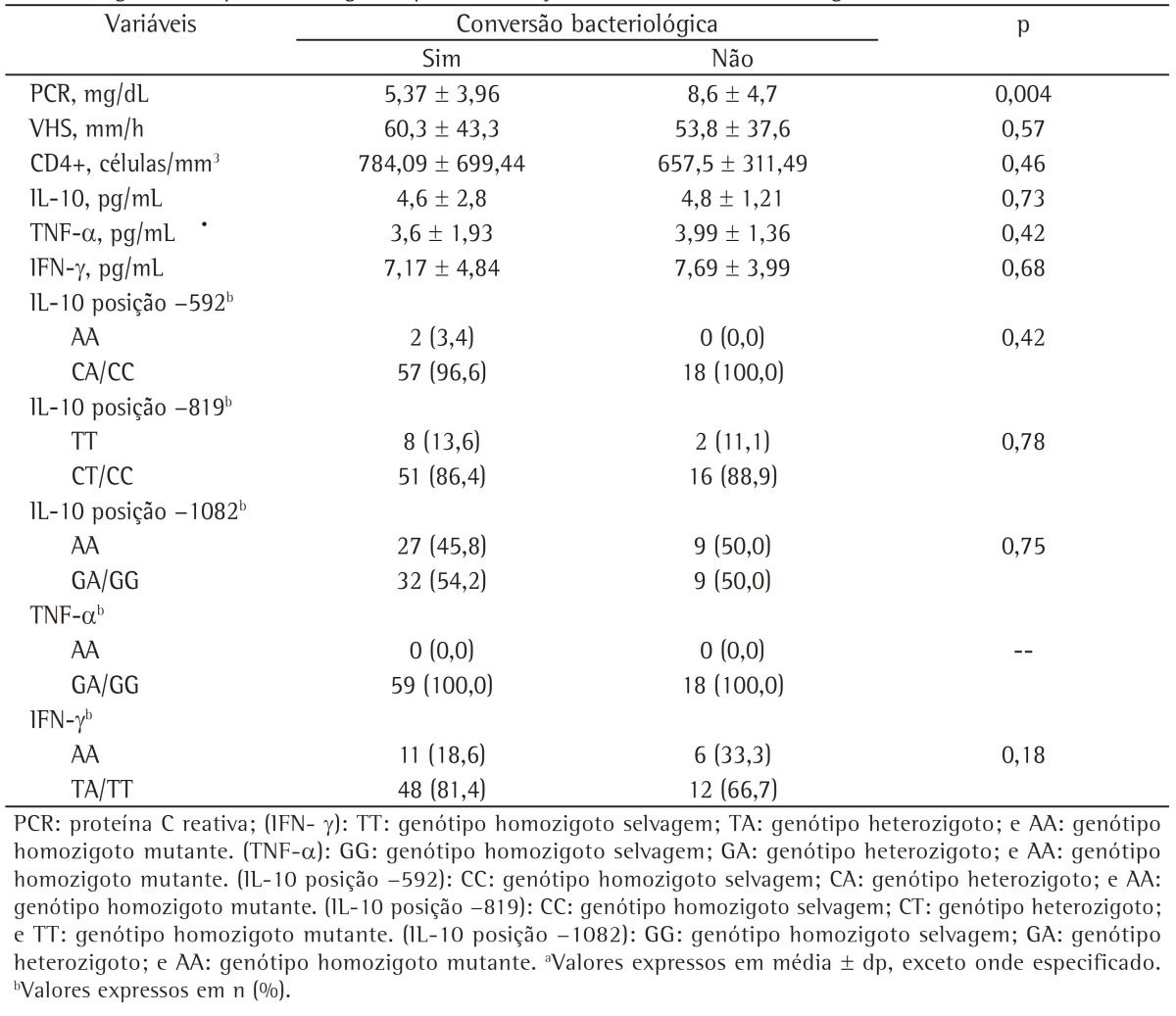

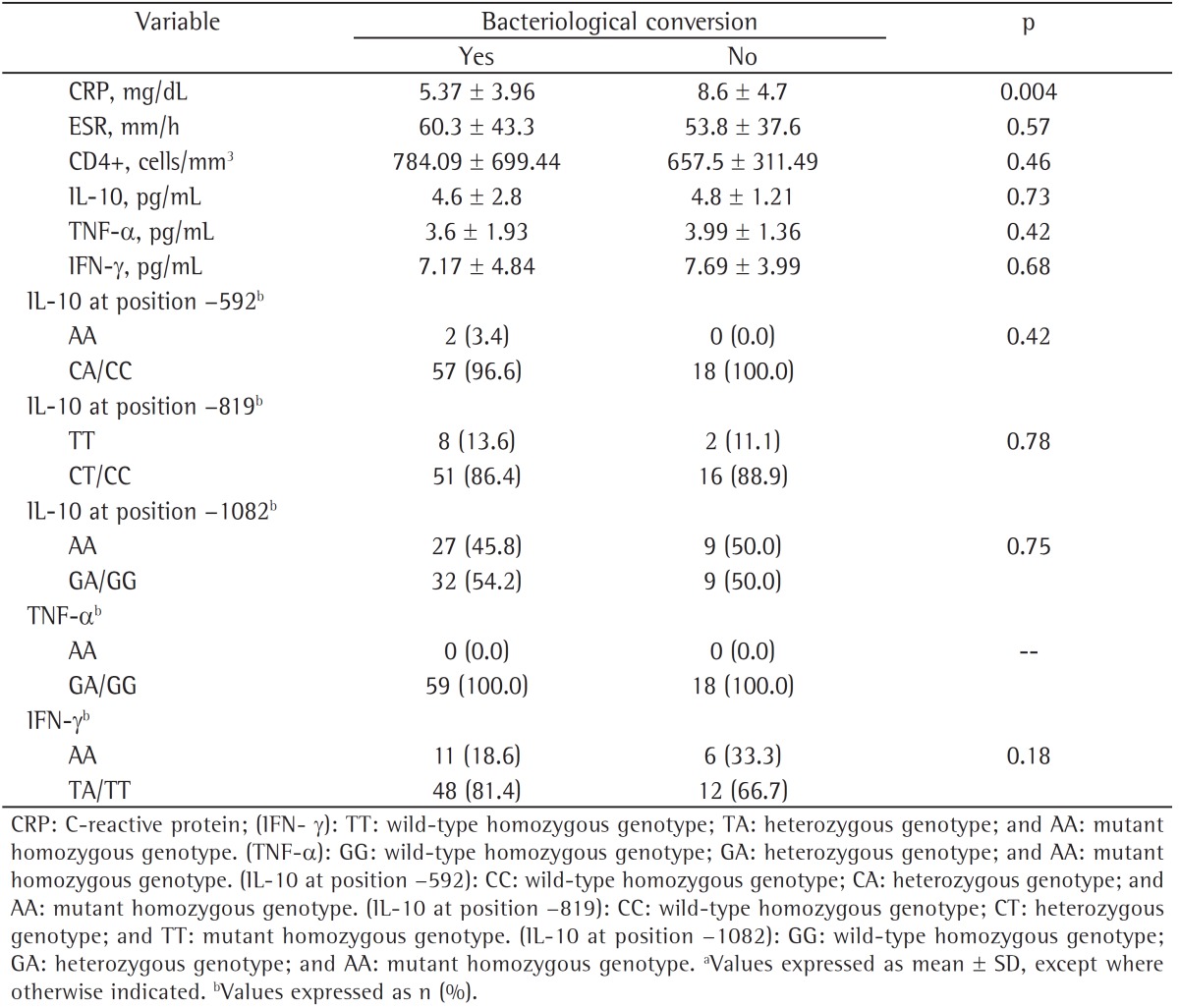

Table 4 shows that lower bacteriological conversion was associated only with high serum levels of CRP. However, by applying the bacteriological conversion coefficient, we found a negative correlation between serum TNF-α levels and bacteriological conversion (r = −0.43; p < 0.001).

Table 4. Serum levels of C-reactive protein, ESR, CD4+, and cytokines, as well as frequency of genotypes, by bacteriological conversion.a.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationships among biochemical markers, inflammatory markers, and immunogenetic markers in pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Brazil. The clinical features of the patients in our sample were similar to those of patients admitted to tuberculosis hospitals in developing countries.(13)

The genetic component of the host response to infection with M. tuberculosis in restricted ethnic groups is evident in the literature.(5) In the present study, the frequency of the mutant allele for IFN-γ gene polymorphisms at position +874 was 0.56, which is similar to that reported by other authors in various countries(14-16) but different from that reported by Fitness et al. in Africa.(17) In addition, the frequency of the mutant allele for TNF-α gene polymorphisms at position +238 was 0.56, which is similar to that reported in other studies.(18-20) In our sample, the allele frequencies for IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592, −819, and −1082 were, respectively, 0.29, 0.43, and 0.68, being similar to those reported in most of the studies included in a meta-analysis.(6) Although our results are consistent with those of various studies, any differences regarding the frequency of these polymorphisms can be explained by ethnic differences among the study populations.

The functional role of allele −238A (TNF-α) in the regulation of TNF-α gene expression was described by Kaluza et al.,(21) whose in vitro studies showed an association between allele −238A and a downregulation of the TNF-α gene (and, consequently, a reduction in TNF-α protein production). Although we found no homozygous mutations, we observed a trend toward low serum levels of TNF-α in patients with a heterozygous genotype, as did Abhimanyu et al.(10) in a population of individuals from India whose ethnic characteristics were quite different from those of our study population. However, Haroon et al.(22) found no association between mutation and cytokine expression in a population of White individuals.

The presence of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the first intron of the IFN-γ gene (at position +874) has been associated with tuberculosis(8,14) and severe tuberculosis.(23) The gene encoding IFN-γ is highly conserved, and few polymorphisms are found in the intragenic region. In our sample, we found no association between IFN-γ gene polymorphisms at position +874 and serum IFN-γ levels, a finding that is similar to those of Abhimanyu et al.(10) and Vidyarani et al.(24) but different from those of Vallinoto et al.,(11) who found low serum levels of IFN-γ in patients with a homozygous mutant genotype at position +874A/A.

We found a significant relationship between high IFN-γ levels and a high ESR, a finding that is consistent with those of Peresi et al.(4) This is possibly due to the fact that the presence of this mutation has been associated with decreased production of IFN-γ (a cytokine that plays an important role in controlling the defense against the pathogen) and, therefore, a diminished acute inflammatory response.

In our study, low serum levels of IL-10 were found to be associated with IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592 and −819 (but not −1082). This finding is similar to those of Abhimanyu et al.(10) and Edwards-Smith et al.,(25) who investigated IL-10 gene polymorphisms at position −1082 and showed that individuals carrying the AA genotype are low IL-10 producers, those carrying the GA genotype are intermediate IL-10 producers, and those carrying the GG genotype are high IL-10 producers; however, the ATA haplotype is associated with low IL-10 production. These discrepant results can be partly explained by the distinct and heterogeneous ethnic characteristics of the study populations.

We observed a trend toward a higher ESR among carriers of IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592 (CA/AA) and −819 (CT/TT). The authors of a recent meta-analysis including 18 studies (none of which included patients from Latin America) were unable to confirm a higher risk of tuberculosis among patients with IL-10 gene polymorphisms at positions −592, −819, or −1082 but found a higher risk of tuberculosis among Europeans with IL-10 gene polymorphisms at position −1082.(6) In that meta- analysis, one of the studies assessing serum IL-10 levels also assessed serum levels of IFN-γ and IL-10. The authors demonstrated that a stronger relationship translated to less severe tuberculosis.

Jamil et al.(26) and Lago et al.(9) suggested that the maintenance of high serum levels of IL-10 during antituberculosis treatment is associated with an increased risk of recurrence, whereas low serum levels of IL-10 usually occur in mild forms of tuberculosis. The results obtained in the present study do not allow us make inferences regarding this issue, given that serum IL-10 levels were assessed only at time point zero and not during clinical follow-up (after completion of antituberculosis treatment).

In the present study, acute inflammatory response markers (CRP levels) were found to be higher in the patients in whom serum TNF-α levels were low (0.0-4.9 pg/mL) than in those in whom serum TNF-α levels were above 5.0 pg/mL. These data suggest that the presence of low concentrations of TNF-α at the time of the initial response against the disease is associated with a worse prognosis and clinical course; however, studies involving larger samples, as well as correlation studies, should be conducted in order to test these hypotheses in the Brazilian population, as mentioned in a review article by Wallis et al.(8) The role of TNF-α in the pathophysiology of tuberculosis has been associated with defense via macrophage activation and the subsequent inflammatory reaction.(3) Our findings reinforce the importance of this cytokine in the host response to M. tuberculosis.

In the present study, an association was found between elevated CRP levels and lower bacteriological conversion at the 8th week of antituberculosis treatment, showing the potential role of this mediator as a marker for monitoring the clinical course of the disease. Some authors have reported that ESR normalization is a marker of good response to treatment in subacute and chronic diseases, such as tuberculosis.(27,28) Various studies have shown increased levels of immune response markers, CRP, and ESR in the initial phase, all of which decrease during treatment.(29,30) Similar results were reported in a study by Peresi et al.,(4) in which CRP levels were significantly decreased only in the 3rd and 6th months of treatment. These findings suggest that CRP can be used in order to evaluate the APR in tuberculosis patients and as a marker of response to antituberculosis treatment, together with the clinical and epidemiological history of such patients.

In our study, there was no association between serum IFN-γ levels and bacteriological conversion, a finding that is similar to those of another study.(8) However, there was an association between initially low serum levels of TNF-α and higher bacteriological conversion. These data are similar to those reported by Su et al.(30) Regarding bacteriological conversion (or lack thereof) and immunological and biochemical variables, we found a positive correlation between the inflammatory marker CRP and the absence of conversion. However, no such correlation was found for the remaining inflammatory markers (ESR and CD4+).

The limitations of the present study include the fact that we did not analyze IL-10 haplotypes, the fact that we did not include other cytokines that play a relevant role in the immune response to active tuberculosis, and the fact that we did not monitor the clinical and bacteriological response of the patients throughout the antituberculosis treatment period.

It is of note that, to our knowledge, this is the first study in Brazil to investigate the presence of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, acute inflammatory response mediators (by measuring serum CRP levels and the ESR), and the genetic background of patients in an attempt to elucidate certain mechanisms of the immunopathogenesis of tuberculosis. Given that this was a descriptive study, there was no control group, which is why we were careful to present the statistical associations without referring to the variables as "risk factors" for any given event.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Tuberculosis Research Center, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Financial support: This study received financial support from the Brazilian Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação (CNPq/MCTI, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development/ National Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation; Grant nos. CNPq/INCT 573548/2008-0 and 478033/2009-5) and the Foundation for the Support of Research in the State of Rio de Ja neiro (Grant no. E:26/110.974/2011).

Contributor Information

Beatriz Lima Alezio Muller, Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Daniela Maria de Paula Ramalho, Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Paula Fernanda Gonçalves dos Santos, Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Eliene Denites Duarte Mesquita, Instituto Estadual de Doenças do Tórax Ary Parreiras, Rio de Janeiro State Department of Health; and Master's Student. Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Afranio Lineu Kritski, Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Martha Maria Oliveira, Graduate Program in Clinical Medicine, Academic Program in Tuberculosis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control - epidemiology, strategy, financing - WHO Report 2009. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministério da Saúde . PNCT - Tuberculose - Situação no Brasil. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottenhoff TH. New pathways of protective and pathological host defense to mycobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20(9):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.06.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peresi E, Silva SM, Calvi SA, Marcondes-Machado J. Cytokines and acute phase serum proteins as markers of inflammatory regression during the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(11):942–949. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008001100009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132008001100009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takiff HE. Host Genetics and Susceptibility. In: Palomino JC, Leao SC, Ritacco V, editors. Tuberculosis 2007 - From Basic Science to Patient Care. Amedeo Challenge. 2007. pp. 207–262. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Chen Y, Nie XB, Wu WH, Zhang H, Zhang M, et al. Interleukin-10 polymorphisms and tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(5):594–601. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.09.0703. http://dx.doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.09.0703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q, Zhan P, Qiu LX, Qian Q, Yu LK. TNF-308 gene polymorphism and tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis involving 18 studies. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(4):3393–3400. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1110-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11033-011-1110-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallis RS, Kim P, Cole S, Hanna D, Andrade BB, Maeurer M, et al. Tuberculosis biomarkers discovery: developments, needs, and challenges. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):362–372. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70034-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lago PM, Boéchat N, Migueis DP, Almeida AS, Lazzarini LC, Saldanha MM, et al. Interleukin-10 and interferon-gamma patterns during tuberculosis treatment: possible association with recurrence. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(5):656–659. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abhimanyu, Mangangcha IR, Jha P, Arora K, Mukerji M, Banavaliker JN, et al. Differential serum cytokine levels are associated with cytokine gene polymorphisms in north Indians with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(5):1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.03.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallinoto AC, Graça ES, Araújo MS, Azevedo VN, Cayres-Vallinoto I, Machado LF, et al. IFNG +874T/A polymorphism and cytokine plasma levels are associated with susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and clinical manifestation of tuberculosis. Hum Immunol. 2010;71(7):692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.03.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BDTMCytometric Bead Array (CBA) Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit II - Instruction Manual. San Jose: Becton, Dickinson and Company BD Biosciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira HM, Brito RC, Kritski AL, Ruffino-Netto A. Epidemiological profile of hospitalized patients with TB at a referral hospital in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(8):780–787. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000800010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132009000800010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amim LH, Pacheco AG, Fonseca-Costa J, Loredo CS, Rabahi MF, Melo MH, et al. Role of IFN-gamma +874 T/A single nucleotide polymorphism in the tuberculosis outcome among Brazilians subjects. Mol Biol Rep. 2008;35(4):563–566. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9123-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11033-007-9123-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sallakci N, Coskun M, Berber Z, Gürkan F, Kocamaz H, Uysal G, et al. Interferon-gamma gene+874T-A polymorphism is associated with tuberculosis and gamma interferon response. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87(3):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.10.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lio D, Marino V, Serauto A, Gioia V, Scola L, Crivello A, et al. Genotype frequencies of the +874T-->A single nucleotide polymorphism in the first intron of the interferon-gamma gene in a sample of Sicilian patients affected by tuberculosis. Eur J Immunogenet. 2002;29(5):371–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.2002.00327.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2370.2002.00327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitness J, Floyd S, Warndorff DK, Sichali L, Malema S, Crampin AC, et al. Large-scale candidate gene study of tuberculosis susceptibility in the Karonga district of northern Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(3):341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh JH, Yang CS, Noh YK, Kweon YM, Jung SS, Son JW, et al. Polymorphisms of interleukin-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha genes are associated with newly diagnosed and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology. 2007;12(4):594–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01108.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira MM, Da Silva JC, Costa JF, Amim LH, Loredo CC, et al. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) of the TNF-α(-238/-308) gene among TB and nom TB patients: Susceptibility markers of TB occurrence? J Bras Pneumol. 2004;30(4):461–467. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ates O, Musellim B, Ongen G, Topal-Sarikaya A. Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28(3):232–236. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9155-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10875-007-9155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaluza W, Reuss E, Grossmann S, Hug R, Schopf RE, Galle PR, et al. Different transcriptional activity and in vitro TNF-alpha production in psoriasis patients carrying the TNF-alpha 238A promoter polymorphism. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114(6):1180–1183. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00001.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haroon N, Tsui FW, Chiu B, Tsui HW, Inman RD. Serum cytokine receptors in ankylosing spondylitis: relationship to inflammatory markers and endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase polymorphisms. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(9):1907–1910. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100019. http://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paletta RM. Fatores de risco associados a ocorrência de tuberculose. [dissertation] Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidyarani M, Selvaraj P, Anand S Prabhu, Jawahar MS, Adhilakshmi AR, Narayanan PR. Interferon gamma (IFNgamma) & interleukin-4 (IL-4) gene variants & cytokine levels in pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124(4):403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards-Smith CJ, Jonsson JR, Purdie DM, Bansal A, Shorthouse C, Powell EE. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism predicts initial response of chronic hepatitis C to interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1999;30(2):526–530. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hep.510300207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamil B, Shahid F, Hasan Z, Nasir N, Razzaki T, Dawood G, et al. Interferon gamma/IL10 ratio defines the disease severity in pulmonary and extra pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2007.03.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubost JJ, Soubrier M, Meunier MN, Sauvezie B. From sedimentation rate to inflammation profile [Article in French] Rev Med Interne. 1994;15(11):727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(05)81398-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0248-8663(05)81398-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahiratmadja E, Alisjahbana B, Boer T de, Adnan I, Maya A, Danusantoso H, et al. Dynamic changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles and gamma interferon receptor signaling integrity correlate with tuberculosis disease activity and response to curative treatment. Infect Immun. 2007;75(2):820–829. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00602-06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00602-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki K, Takashima Y, Yamada T, Akiyama J, Yagi K, Kawashima M, et al. The sequential changes of serum acute phase reactants in response to antituberculous chemotherapy [Article in Japanese] Kekkaku. 1992;67(4):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su WL, Perng WC, Huang CH, Yang CY, Wu CP, Chen JH. Association of reduced tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, and interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) but increased IL-10 expression with improved chest radiography in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(2):223–231. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00381-09. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00381-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]