Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Because pulmonary embolism (PE) and COPD exacerbation have similar presentations and symptoms, PE can be overlooked in COPD patients. Our objective was to determine the prevalence of PE during COPD exacerbation and to describe the clinical aspects in COPD patients diagnosed with PE.

METHODS:

This was a prospective study conducted at a university hospital in the city of Ankara, Turkey. We included all COPD patients who were hospitalized due to acute exacerbation of COPD between May of 2011 and May of 2013. All patients underwent clinical risk assessment, arterial blood gas analysis, chest CT angiography, and Doppler ultrasonography of the lower extremities. In addition, we measured D-dimer levels and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) levels.

RESULTS:

We included 172 patients with COPD. The prevalence of PE was 29.1%. The patients with pleuritic chest pain, lower limb asymmetry, and high NT-pro-BNP levels were more likely to develop PE, as were those who were obese or immobile. Obesity and lower limb asymmetry were independent predictors of PE during COPD exacerbation (OR = 4.97; 95% CI, 1.775-13.931 and OR = 2.329; 95% CI, 1.127-7.105, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS:

The prevalence of PE in patients with COPD exacerbation was higher than expected. The association between PE and COPD exacerbation should be considered, especially in patients who are immobile or obese.

Keywords: Pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive; Pulmonary embolism; Risk factors

Introduction

Not only is COPD a significant cause of morbidity worldwide, but it is also the fourth-leading cause of mortality today and is estimated to be the third-leading cause of death by 2020. Exacerbations of COPD are the episodic periods of the disease, characterized by deterioration of respiratory function. Most deaths caused by COPD appear to occur during exacerbations. Respiratory infections are responsible for 50-70% of COPD exacerbations, and environmental pollution causes another 10%. Nearly 30% of all COPD exacerbations have unknown etiology. (1,2) Although a meta-analysis found that the prevalence of pulmonary embolism (PE) was 20% among patients who were in a period of exacerbation of COPD,(3) that prevalence was found to be 13.7% in a recent study.(4) The prevalence of PE in post-mortem studies ranges from 28% to 51%.(5,6)

The presentation of common symptoms of COPD exacerbations, such as dyspnea and cough, might cause the diagnosis of acute PE to be overlooked. Patients with COPD are at risk of developing PE due to various reasons, such as immobility, systemic inflammation, and polycythemia. In addition, COPD has been recently defined as an independent risk factor for PE.(7) Mortality and delay in diagnosis of PE are higher in patients with COPD.(8) The prevalence of PE in a highly specific group of patients who were hospitalized for severe exacerbation with unknown origin was reported to be 25%.(9) Gunen et al. reported that venous thromboembolism (VTE) was three times more prevalent in patients with an exacerbation of unknown origin than in patients with an exacerbation of known origin.(4) The exact prevalence of PE in patients who are in a period of an acute exacerbation of COPD and the clinical features of those patients are as yet unclear. The objective of the present study was to determine the prevalence of PE in patients during COPD exacerbation and to describe the clinical aspects in those patients diagnosed with PE.

Methods

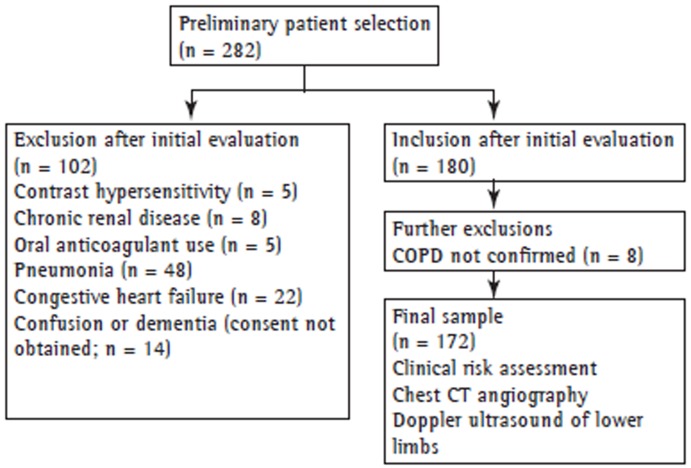

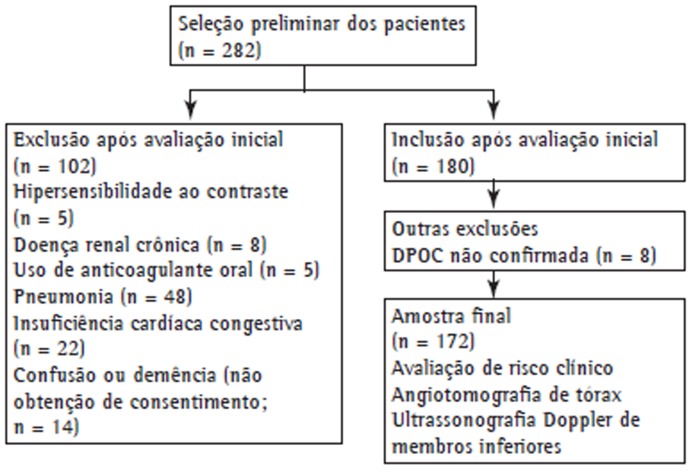

This was a prospective study conducted in a university hospital in the city of Ankara, Turkey. All COPD patients who were hospitalized due to acute exacerbation of COPD between May of 2011 and May of 2013 were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ufuk University, located in Ankara, Turkey. All participating patients gave written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were having a history of hypersensitivity after the injection of contrast material; having chronic renal disease, pneumonia, or congestive heart failure; having been under anticoagulant treatment; and being unable to give written informed consent because of confusion or dementia. Patients with an inconclusive diagnosis of COPD were also excluded. As a result, a total of 172 patients were included in the study. Figure 1 shows the design of the study.

Figure 1. Study design.

The diagnosis of COPD was confirmed by medical history and previous medical records (chest X-rays and pulmonary function testing). The severity of COPD was determined by using the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria. Acute exacerbation was diagnosed when the patient with COPD had a worsening in respiratory symptoms beyond the normal day-to-day variations that led to a change in medication.(10)

Detailed clinical evaluations were performed for all participants by medical history, physical examination, and chest X-rays. Blood samples were taken immediately for the evaluation of D-dimer, blood workup, arterial blood gas analysis, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) levels. D-dimer levels were measured with the Tina-quant(r) D-dimer assay system (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), which is a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay. We used Roche Elecsys ProBNP assay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in order to determine NT-pro-BNP levels.

Risk factors for developing VTE, such as surgery, malignancy, immobility (bed rest > 48 h), and previous VTE, were noted while recording the history of the patient. We used the simplified version of the revised Geneva score,(11) Well's score,(12) and the clinical classification proposed by Miniati et al.(13) in all patients who were included in the study.

Chest CT angiography (CTA) was performed with a 16-section multidetector CT scanner (GE Light Speed 16; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) within 24 h of admission. The patients were injected 100 mL of non-ionic contrast media (Iohexol Omnipaque 300/100; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) via an 18G needle into the antecubital vein at a rate of 4 mL/s using a power injector (Medrad Stellant Dual; Medrad, Indianola, PA, USA). Chest CTA was carried out using a dedicated workstation (Advanced Workstation 4.0; GE Healthcare). The diagnosis of PE was reached when an intraluminal filling defect surrounded by intravascular contrast or total occlusion of the pulmonary arterial lumen was detected at any level of the pulmonary arteries. The localization of the thrombi was noted.

Doppler ultrasonography of the deep veins of the lower extremities was performed by an experienced radiologist who was blinded about the angiographic results. A standard method was used with a dedicated ultrasound unit (Logiq 7(r); GE Healthcare) and a 10L linear array transducer (bandwidth, 6-10 MHz) in order to investigate the presence/absence of intravenous thrombi.

Arterial blood gas analyses were performed with a GEM PremierTM 3000 blood gas/electrolyte analyzer (model 570; Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA, USA). Interpretation of the results was as follows: acidosis, pH < 7.35; alkalosis, pH > 7.45; hypercapnia, PaCO2 > 45 mmHg; hypocapnia, PaCO2 < 35 mmHg; and hypoxemia, PaO2 < 80 mmHg. Hypoxemia was further graded as mild (60-80 mmHg); moderate (40-59 mmHg); or severe (< 40 mmHg).(14)

Patients were considered obese with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m²,(15) whereas a diagnosis of cachexia was given to male patients with a BMI < 16 kg/m2 and to female patients with a BMI < 15 kg/m2.(16)

A diagnosis of hypertension was confirmed when blood pressure was > 140/90 mmHg on three separate occasions after hospital admission. (17) A diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was based on the American Diabetes Association criteria.(18) The participants on antihypertensive or antidiabetic treatment were considered to have hypertension or diabetes mellitus. A diagnosis of coronary artery disease was based on previous medical records (echocardiogram and CTA) of the patients. Anemia was diagnosed based on hemoglobin levels (< 13.5 g/dL in males > 18 years of age and < 12.0 g/dL in females > 18 years of age).(19)

The data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 11.5 pocket program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies, whereas continuous variables were expressed as means, standard deviations, medians, minimum values, and maximum values. The chi-square test was used in order to compare two independent groups of categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used in order to compare two independent groups of continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at a value of p < 0.05. Variables with p < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were evaluated by multiple logistic regression analysis in order to define independent risk factors of outcome variables.

Results

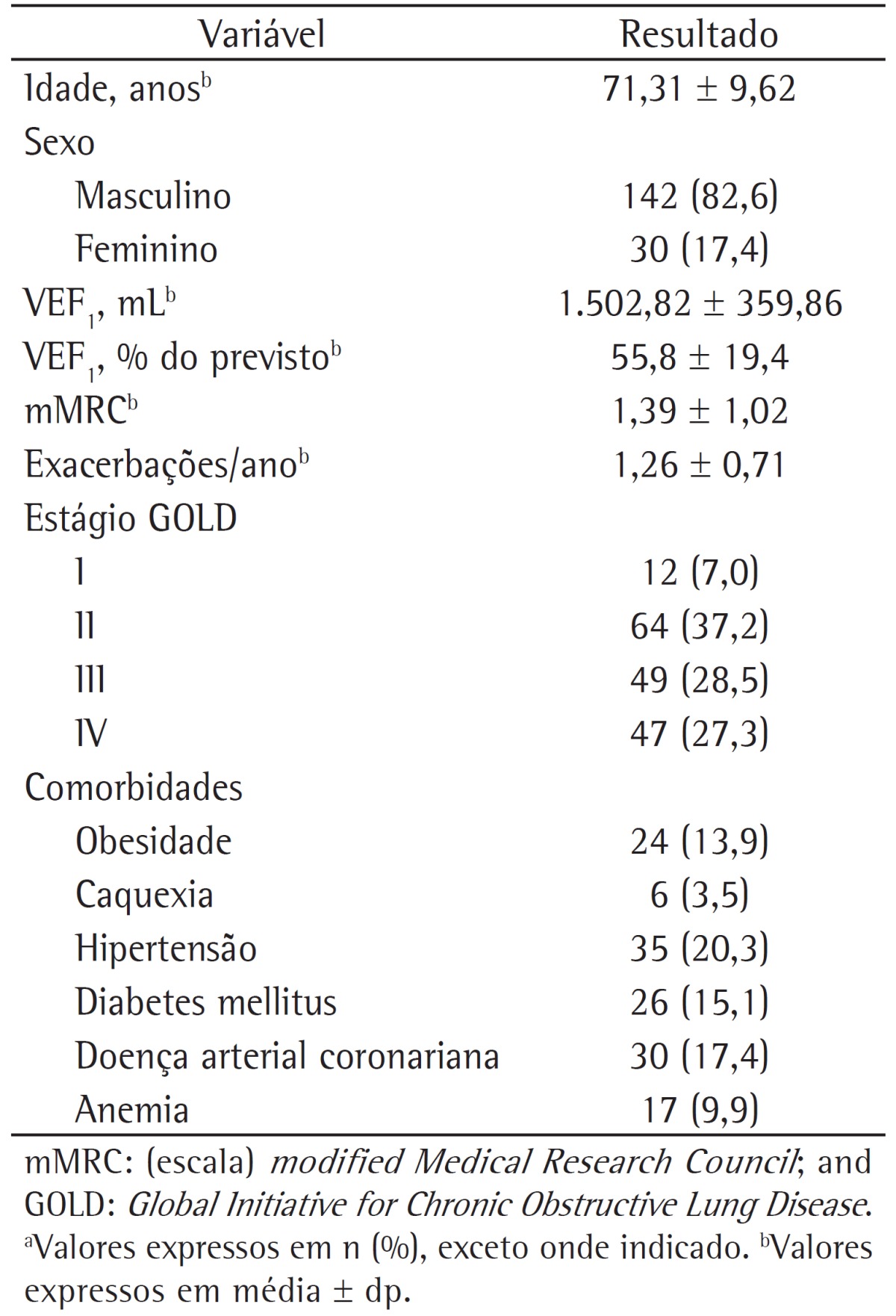

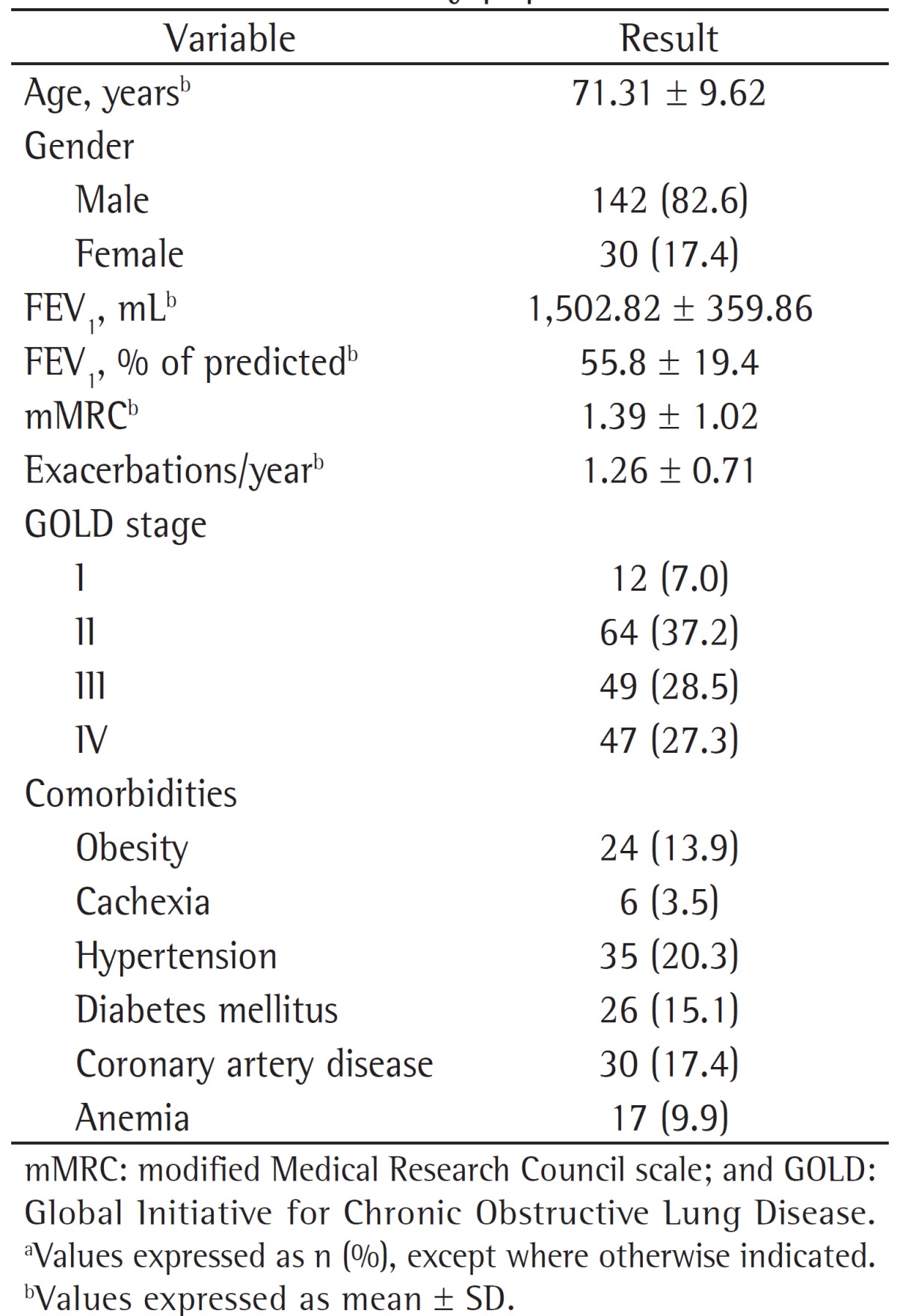

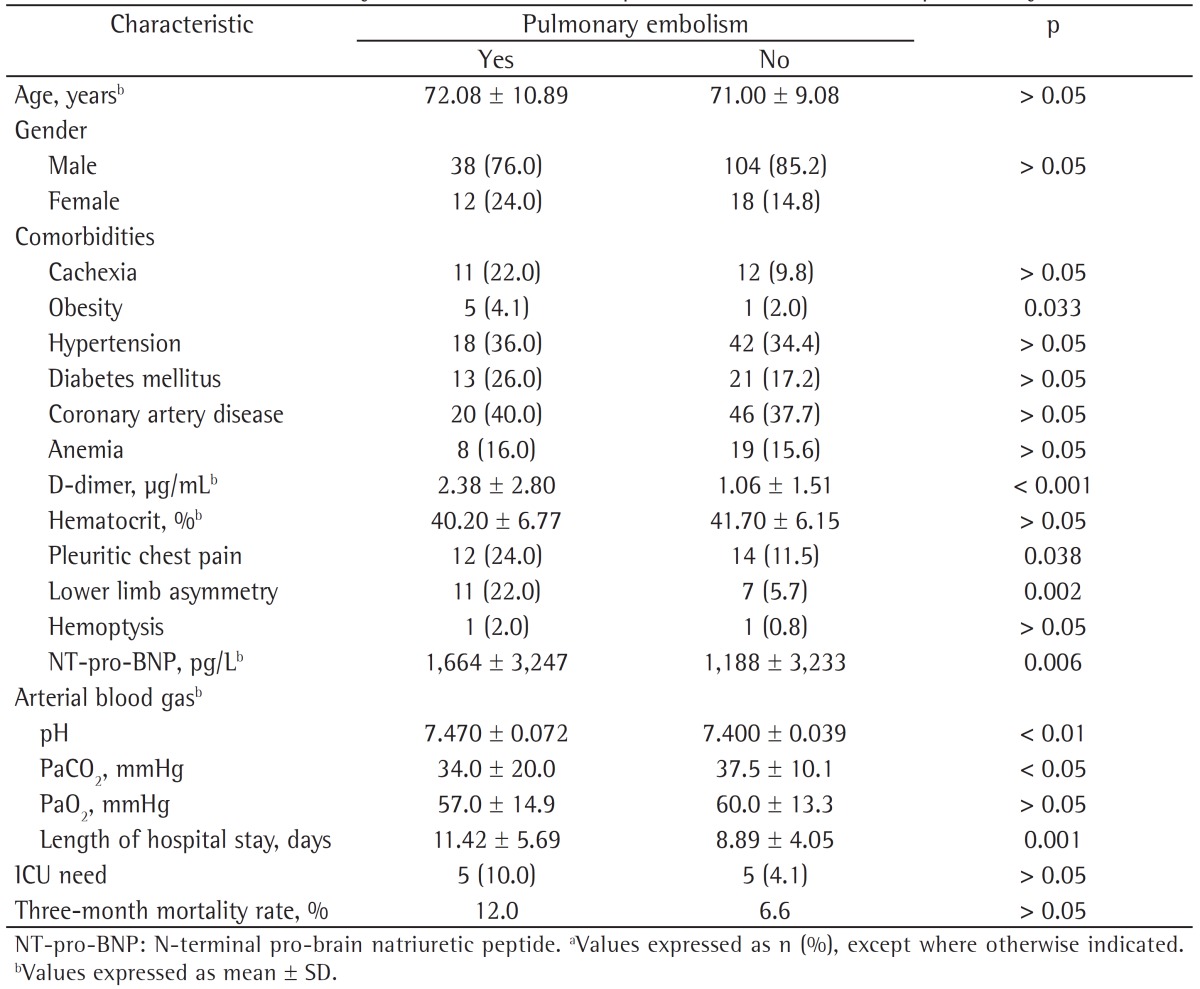

A total of 172 patients were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 71.31 ± 9.62 years; 142 patients (82.6%) were male, and 30 patients (17.4%) were female. The distribution of patients according to GOLD stages (GOLD I-IV) were as follows: 7.0%, 37.2%, 28.5%, and 27.3%, respectively. Most of the patients (73.8%) had comorbidities accompanying COPD. Demographic properties and basic clinical characteristics of the COPD patients who were included in the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic properties and general clinical characteristics of the study population.a.

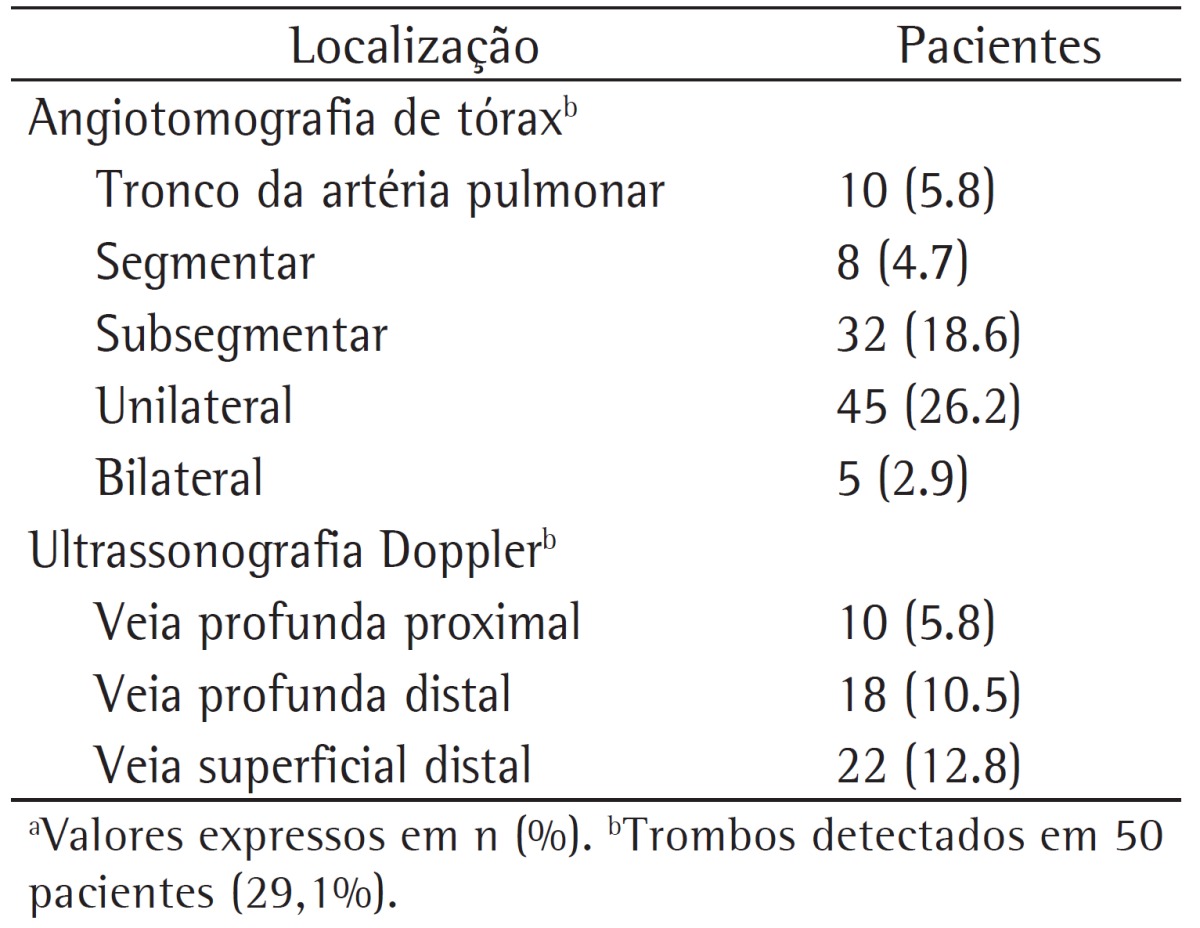

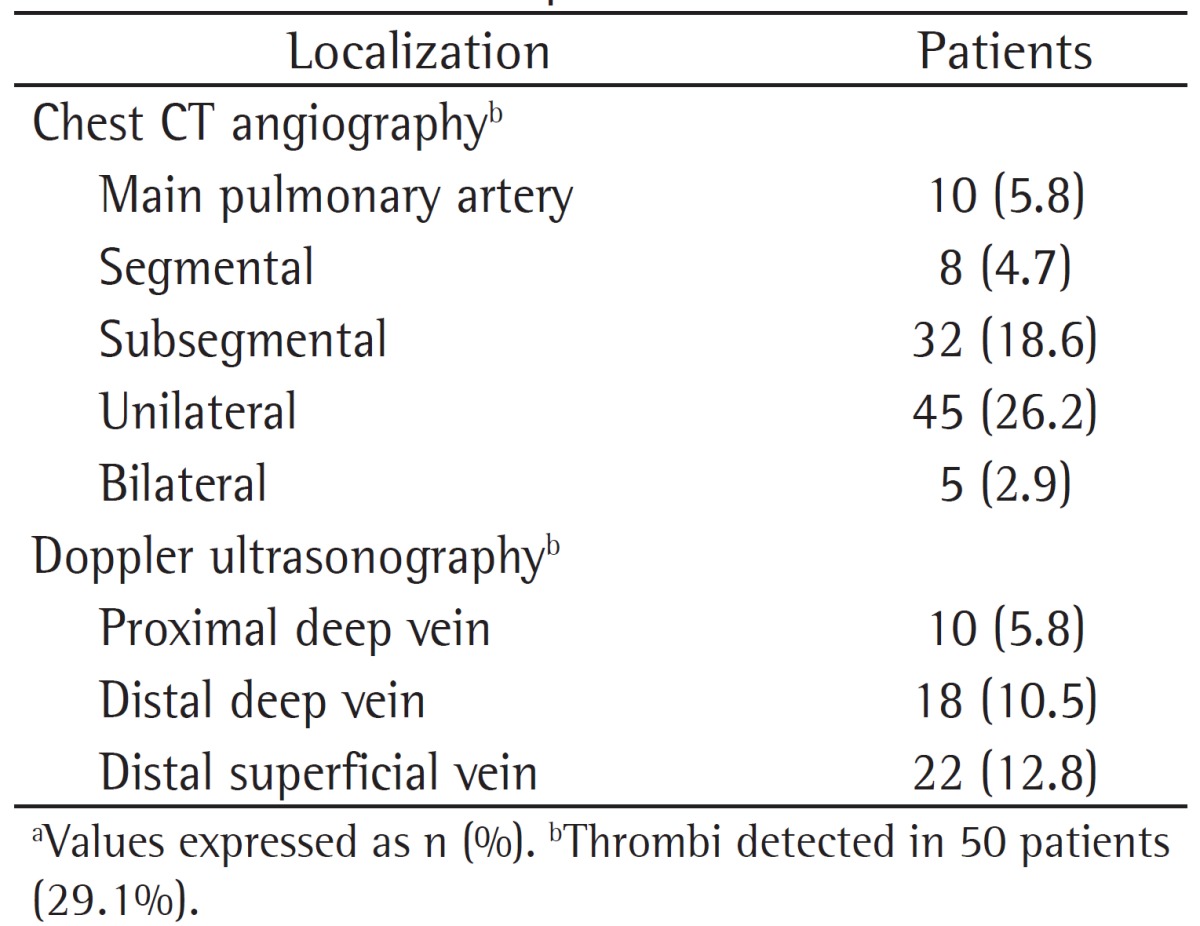

The prevalence of PE was 29.1%, and all of the patients who had PE based on CTA results also had deep vein thrombosis. The prevalence of PE did not differ between GOLD stages (p > 0.05). The localization of thrombi in patients who had PE and the results of the Doppler ultrasonography are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Localization of the thrombi on chest CT angiography and Doppler ultrasonography of the lower limbs in the 172 patients studied.a.

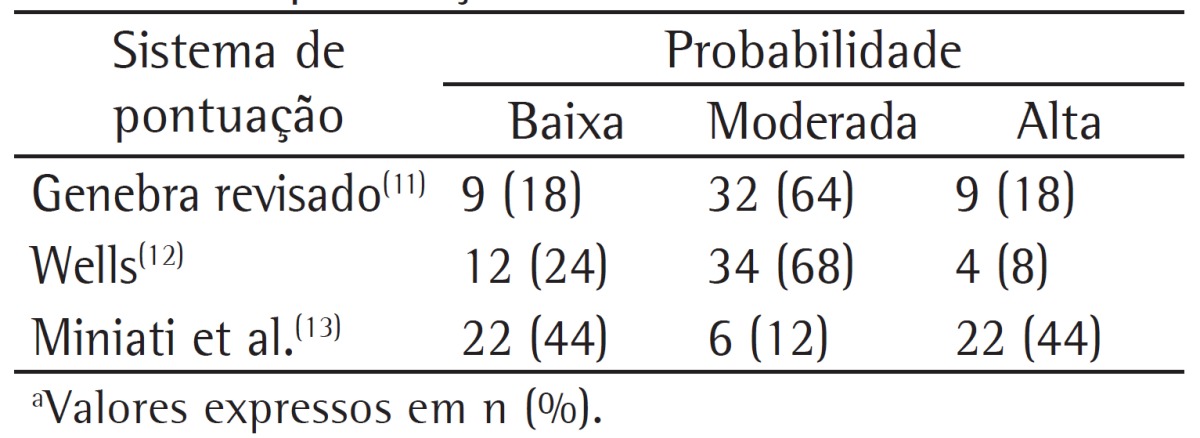

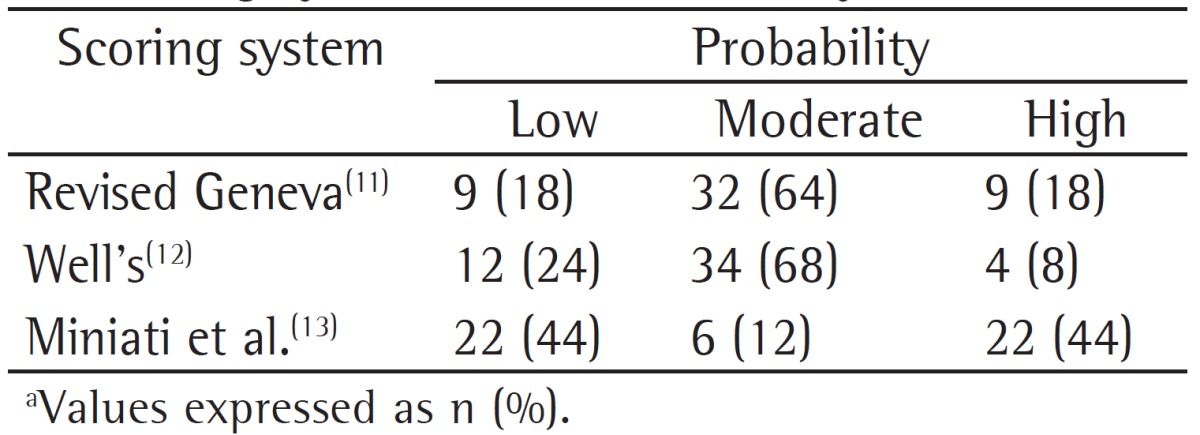

The ratios of low probability according to the revised Geneva score,(11) Well's score,(12) and the clinical classification by Miniati et al.(13) in patients who had a confirmed diagnosis of PE was 18%, 24%, and 44%, respectively. The clinical probabilities of the patients who were diagnosed with PE (positive results on CTA) according to the three abovementioned scores are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Clinical probabilities of the 50 patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism according to the scoring systems used in the study.a.

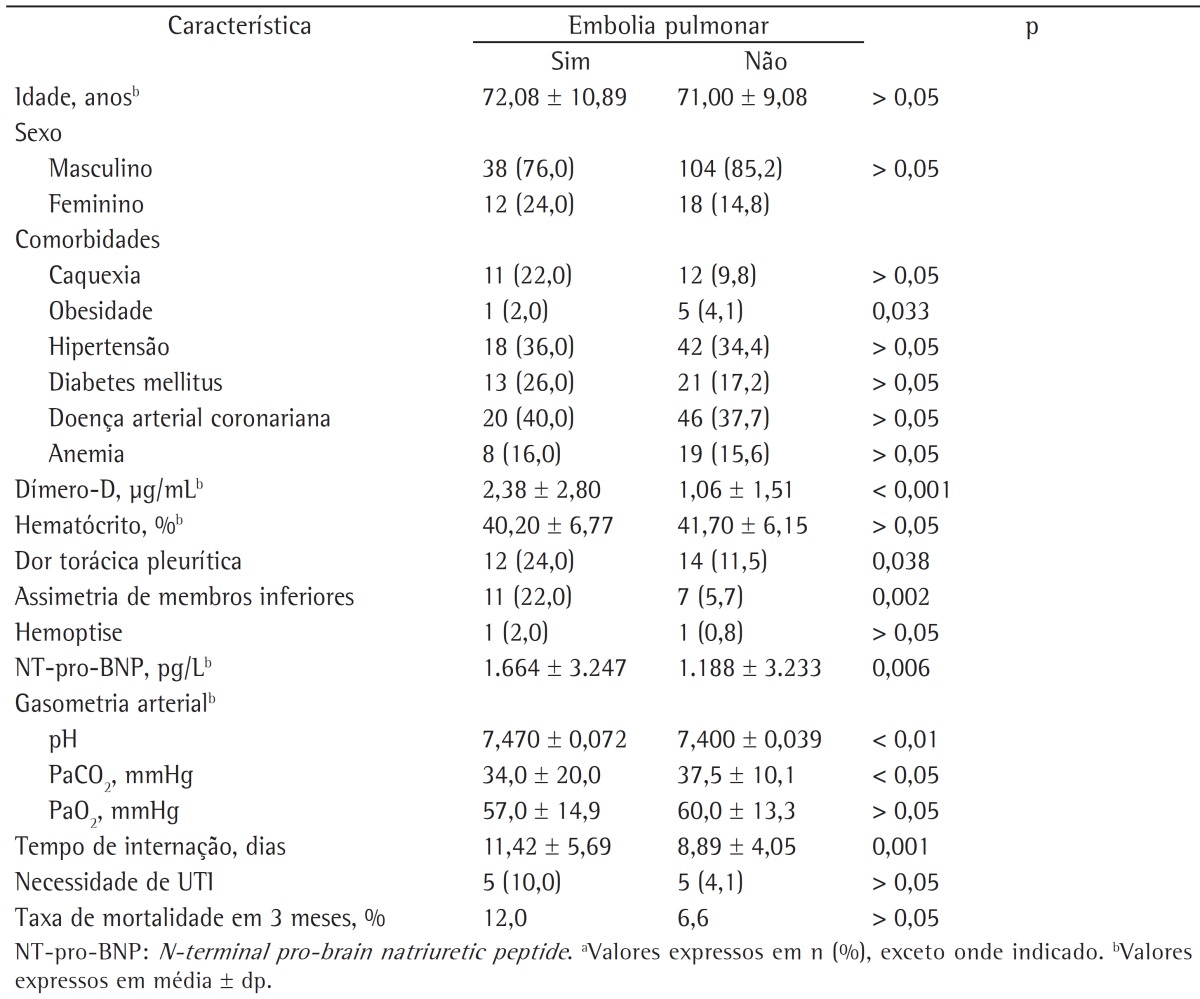

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups of patients with PE and without PE in terms of age, gender distribution, and presence/number of accompanying comorbidities (p > 0.05 for all). The prevalence of obesity was significantly higher among the patients with PE (p = 0.033). The prevalence of other comorbidities (cachexia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and anemia) was not different between the groups with or without PE (p > 0.05). However, the prevalence of immobility was significantly higher among those with PE (p = 0.024). Risk factors for VTE (trauma, malignancy, surgery, congestive heart failure, or previous history of VTE) did not significantly differ between the two groups (p > 0.05). In addition, the presence of symptoms, such as cough, sputum, hemoptysis, dyspnea, tachycardia, fever, etc., did not significantly differ between the two groups (p > 0.05). Pleuritic chest pain and lower limb asymmetry were significantly more prevalent among those diagnosed with PE (p = 0.038, and p = 0.002, respectively).

Levels of D-dimers and NT-pro-BNP were significantly higher among the patients with PE than among those without (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.006). Arterial blood gas analyses revealed that the patients with PE had higher pH values and lower PaCO2 levels than did those without (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). The length of hospitalization was longer in the patients with PE than in those without (p = 0.001). However, the three-month mortality rate and the need for intensive care did not differ between the groups (p > 0.05). The clinical and laboratory findings in the patients with and without PE are compared in Table 4.

Table 4. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients with and without pulmonary embolism.a.

Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that obesity and lower limb asymmetry were the independent variables that predicted the presence of PE in the patients with COPD (OR = 4.97; 95% CI, 1.775-13.931 and OR = 2.329; 95% CI, 1.127-7.105, respectively).

Discussion

The present study showed that PE was present in 29.1% of the patients who were hospitalized due to an exacerbation of COPD. Patients with pleuritic chest pain, lower limb asymmetry, and high NT-pro-BNP levels were more likely to develop PE, as were those who were obese or immobile. Obesity and lower limb asymmetry were independent predictors of PE in the patients with COPD exacerbation.

Most deaths caused by COPD occur during the periods of exacerbation. The course of the disease can be worsened by PE. Because clinical features of PE are nonspecific (e.g., dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain), it might be underdiagnosed in patients with COPD during periods of exacerbation. Visual confirmation of the clot with an imaging technique is required in order to warrant anticoagulation therapy in appropriate dose and duration. The prevalence of PE in COPD exacerbations is not precisely known, but a recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of PE in COPD exacerbation with an unknown cause was 20%. The prevalence was higher (24.7%) in four studies that included hospitalized COPD patients.(3) However, Tillie-Leblond et al. found the prevalence of PE to be 25% in COPD patients with severe exacerbation of unknown origin.(9) In our study, we also evaluated the prevalence of PE among hospitalized patients with COPD exacerbation, and it was even higher (29.1%).

Gunen et al. found the prevalence of PE among patients who were hospitalized due to COPD exacerbation to be 13.7%,(4) which was lower than that in our study. They found that being female, having chest pain, having hypotension, and having syncope to be predictors of PE in patients with COPD exacerbation. Our study did not reveal a significant relationship between the genders. Similarly, we found positive relationships of pleuritic chest pain and lower limb asymmetry with the occurrence of PE. Gunen et al. found that none of the patients with low-risk determination and 20.7% of those with moderate-risk determination had PE. In contrast, our study showed that, among the patients with PE, 24% had a low clinical probability, and 68% had a moderate clinical probability according to the Well's score. Fernández et al. reported that patients with PE and COPD had a lower pre-test probability for PE than the patients with PE but without COPD.(8) In the present study, a low probability according to all three scoring systems (revised Geneva, Well's and Miniati et al.)(11-13) could not rule out PE in the patients with COPD exacerbation. These results showed that the clinical risk assessment of patients with COPD exacerbation for PE can mislead clinicians. The presence of common symptoms in COPD exacerbation and PE might be the reason that causes a high incidence of low-risk probability in these patients. COPD has been recently defined as an independent risk factor for PE.(7) Further studies are necessary to evaluate the inclusion of COPD to the criteria for the clinical risk assessment for PE in order to overcome this problem.

The variation in the prevalence of PE is thought to be the result of differences in study populations and study design. The prevalence of PE in COPD patients who were admitted to the emergency department was reported to be 3.3% in a study.(20) The low prevalence in that study might result from the evaluation of patients admitted to the emergency department. Additionally, the authors did not further evaluate the COPD patients who did not have a clinical suspicion of PE and had low D-dimer levels (< 0.5 µg/mL). We evaluated all hospitalized patients with COPD exacerbation using imaging methods without considering their clinical probabilities for PE and D-dimer levels. In a recent study by Choi et al., the prevalence of PE among hospitalized patients with COPD exacerbation was distinctly lower than that in our study (5% vs. 29.1%), despite the similarities in the selected population and the design of the two studies.(21) In contrast to their study, however, the location of PE in most of our patients was peripheral. In both studies, NT-pro-BNP levels were significantly higher in COPD patients with PE. Although the length of hospital stay was longer in the COPD patients with PE in our study, that study did not reveal a difference between the two groups in terms of length of hospital stay.

In contrast to the study by Gunen et al., which reported no difference in PaCO2 levels in COPD patients with or without PE,(4) the present study showed that respiratory alkalosis and hypocapnia were more common in patients with COPD exacerbation accompanying PE. Tillie-Leblond et al. found lower PaCO2 levels in patients with COPD exacerbation and PE.(9) Similarly, previous reports showed that a decrease in PaCO2 during COPD exacerbation might indicate PE.(22,23)

It is known that BNP is released from the heart into the circulation. Levels of BNP increase in patients with congestive heart failure and acute myocardial infarction; BNP is also a marker of right ventricular dysfunction in acute PE(24) and correlates with pulmonary arterial pressure.(25) Gunen et al. showed that indicators of acute right heart failure on echocardiogram were more prevalent in COPD patients with PE.(4) In our study, we excluded the patients with congestive heart failure on their initial evaluation. NT-pro-BNP levels were significantly higher in COPD patients with PE than in those without PE. Echocardiograms require expertise and cannot be performed at all medical centers. However, NT-pro-BNP measurements might be more accessible for the evaluation of right heart failure and pulmonary arterial pressure in COPD patients without congestive heart failure who are being investigated for PE.

A few symptoms are closely related to the localization of the thrombus in patients with PE. Hypotension and syncope were more common symptoms in the study by Gunen et al., which can be explained based on the location of the thrombi (half of the patients with PE had a centrally located thrombus).(4) In the present study, the thrombi in patients with COPD exacerbation and PE were most commonly peripheral (segmental and subsegmental) in 80% of the patients, and pleuritic chest pain was the most common symptom. In our study population, the peripheral location of most of the thrombi might be the reason of the similar mortality rates in the COPD patients with and without PE. However, it is important to detect and properly treat a peripherally located thrombus in order to prevent recurrence, which might cause death.

Our study had some limitations. Although this was the largest study to evaluate the prevalence and the characteristics of patients with COPD exacerbation associated with PE, it was a single center study. In addition, the present study only investigated the prevalence of PE and the clinical conditions in which PE was suspected in the patients with COPD exacerbation.

In conclusion, the prevalence of PE in the patients with COPD exacerbation was higher than expected in our study. Exacerbation of COPD and PE can be associated. Because of that, PE should be considered in patients with COPD exacerbation, especially in those who are immobile, have pleuritic chest pain, and present high D-dimer, NT-pro-BNP, and pH levels, as well as presenting low PaCO2 levels. Obesity and lower limb asymmetry were independent predictors of the presence of PE in our patients. Larger studies are necessary in order to evaluate the prevalence of PE in patients with COPD exacerbation in a more precise fashion and to provide understanding about the factors and mechanisms that influence the development of PE in this population.

Footnotes

Study carried out in the Department of Chest Diseases, Ufuk University, Ankara, Turkey.

A versão completa em português deste artigo está disponível em www.jornaldepneumologia.com.br

Contributor Information

Evrim Eylem Akpinar, Department of Chest Diseases, Ufuk University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Derya Hoşgün, Department of Chest Diseases, Ufuk University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Serdar Akpýnar, Atatürk Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training Hospital, Ankara, Turkey.

Gökçe Kaan Ataç, Department of Radiology, Ufuk University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Beyza Doğanay, Department of Biostatistics, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Meral Gülhan, Department of Chest Diseases School of Medicine, Ufuk University, Ankara, Turkey.

References

- 1.Sapey E, Stockley RA. COPD exacerbations . 2: Aetiology . Thorax. 2006;61(3):250–258. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2005.041822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seneff MG, Wagner DP, Wagner RP, Zimmerman JE, Knaus WA. Hospital and 1-year survival of patients admitted to intensive care units with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 1995;274(23):1852–1857. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530230038027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizkallah J, Man SF, Sin DD. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and metanalysis. Chest. 2009;135(3):786–793. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunen H, Gulbas G, In E, Yetkin O, Hacievliyagil SS. Venous thromboemboli and exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(6):1243–1248. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00120909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum GL, Fisher FD. The relationship of fatal pulmonary insufficiency with cor pulmonale, rightsided mural thrombi and pulmonary emboli: a preliminary report. Am J Med Sci. 1960;240:609–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell RS, Silvers GW, Dart GA, Petty TL, Vincent TN, Ryan SF, et al. Clinical and morphologic correlations in chronic airway obstruction. Aspen Emphysema Conf. 1968;9:109–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poulsen SH, Noer I, Møller JE, Knudsen TE, Frandsen JL. Clinical outcome of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. A follow-up study of 588 consecutive patients. J Intern Med. 2001;250(2):137–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00866.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández C, Jiménez D, De Miguel J, Martí D, Díaz G, Sueiro A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism [Article in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2009;45(6):286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2008.10.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tillie-Leblond I, Marquette CH, Perez T, Scherpereel A, Zanetti C, Tonnel AB, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with unexplained exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(6):390–396. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00005. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD . [homepage on the Internet] Bethesda: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease ; Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD - Revised 2011. [Adobe Acrobat document, 90p.]; [cited 2013 Aug 26]. 2011. a Available from: Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klok FA, Mos IC, Nijkeuter M, Righini M, Perrier A, Le Gal G, et al. Simplification of the revised Geneva score for assessing clinical probability of pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2131–2136. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.19.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells PS, Owen C, Doucette S, Ferguson D, Tran H. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA. 2006;295(2):199–207. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.2.199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miniati M, Prediletto R, Formichi B, Marini C, Di Ricco G, Tonelli L, et al. Accuracy of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):864–871. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9806130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9806130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose BD, TW Post. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. New York: McGraw Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Obesity in Adults. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):53–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carretero OA, Oparil S. Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology . Circulation. 2000; 101(3):329–335. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33 Suppl 1:S62–S69. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc10-S062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White CT, Barrett BJ, Madore F, Moist LM, Klarenbach SW, Foley RN, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for evaluation of anemia. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;(110):S4–S6. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ki.2008.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutschmann OT, Cornuz J, Poletti PA, Bridevaux PO, Hugli OW, Qanadli SD, et al. Should pulmonary embolism be suspected in exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Thorax. 2007;62(2):121–125. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.065557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi KJ, Cha SI, Shin KM, Lee J, Hwangbo Y, Yoo SS, et al. Prevalence and predictors of pulmonary embolism in Korean patients with exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2013;85(3):203–209. doi: 10.1159/000335904. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000335904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lippmann M, Fein A. Pulmonary embolism in the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease A diagnostic dilemma. Chest. 1981;79(1):39–42. doi: 10.1378/chest.79.1.39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.79.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodger MA, Jones G, Rasuli P, Raymond F, Djunaedi H, Bredeson CN, et al. Steady-state end-tidal alveolar dead space fraction and D-dimer: bedside tests to exclude pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2001;120(1):115–119. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klok FA, Mos IC, Huisman MV. Brain-type natriuretic peptide levels in the prediction of adverse outcome in patients with pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(4):425–430. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-459OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200803-459OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yetkin Ö, In E, Aksoy Y, Hacıevliyagil SS, Günen H. Brain natriuretic peptide in acute pulmonary embolism: its association with pulmonary artery pressure and oxygen saturations. Turkish Resp J. 2006;7(3):105–108. [Google Scholar]