Abstract

Although substance abuse treatment has been considerably scaled up in China, impediments to accessing these services remain among drug users. The authors examine the primary psychosocial barriers to drug treatment in this population and evaluate factors associated with these barriers. Barriers to accessing drug treatment were measured using the Barriers to Treatment Inventory (BTI). A Structural Equation Model was used to examine whether the internal barriers were associated with treatment history and frequent methamphetamine use as well as how demographic characteristics influence such barriers. We found four primary factors of internal barriers to drug treatment – absence of problem, negative social support, fear of treatment, and privacy concerns – to fit well. Demographic factors, notably age and employment status, indirectly influence barriers to treatment via other factors. Frequency of methamphetamine use and drug treatment history are directly associated with the absence of problem and negative social support dimensions of the BTI, and it is through these pathways that demographic factors such as age and employment status shape barriers to treatment. The findings indicate that perceived absence of a problem and negative social support are the barriers most influenced by the personal domains of Chinese drug users’ lives. Efforts to engage drug users in China about drug treatment options may consider how these barriers are differentially perceived in order to effectively reach this population.

Keywords: drug treatment, barriers, China

1. Introduction

China has experienced a considerable scale up of drug treatment in response to increasing numbers of drug users following social and economic reforms over the past two decades. This scale up has included both increasing availability of treatment and expanding options for treatment. Options available to drug users in China include treatment modalities commonly found in medicalized settings in Western nations, such as opiate substitution therapies and the use of opiate antagonists and non-opiate agents (Tang and Hao, 2007). Beyond these treatment options, traditional Chinese medicinal therapies, including acupuncture and herbal remedies, are available through China’s formal health sector (Shi et al, 2006). Such options provide alternatives for those averse to biomedical treatments, and further enable points of contact with health care. Additionally, psychosocial interventions have become more widely available and integrated within comprehensive drug treatment programs. Yet, the drug treatment system in China is still evolving, especially as the infrastructure expands to meet the needs of users of nonopiate substances. This aspect is of significant recent concern since, although heroin remains a primary drug of dependence in China, other drugs – most notably methamphetamine and ketamine – have grown increasingly common (Huang et al, 2011). Among registered drug users in 2004 only 1.7% used amphetamines, but prevalence grew to 11.1% by 2007 (Zhao, 2008). While complete epidemiological data on prevalence remains underdeveloped, methamphetamine seizures in China have continued to increase in recent years and other sentinel systems suggest that the methamphetamine problem in China is entrenched (UNODC, 2013).

Despite advances in treatment programs, many Chinese drug users remain wary about entering treatment. Such concerns are common among drug users around the world, as they express reservations about entering treatment in many contexts (Rapp et al., 2006). Various barriers to treatment serve as obstacles in the difficult pathway to recovery. Studies indicate that many factors -including perceived lack of problem, apprehension about social support, stigma, concern about privacy loss, fears of the treatment process, discomfort disclosing problems, and fears of life disruption - impede linkages to treatment (Cunningham et al., 1993; Appel et al., 2004; Rapp et al., 2006). Certainly, there is evidence that structural barriers to drug treatment in China remain (Qi et al., 2013). Yet, research has demonstrated that drug users’ motivations for entering drug treatment are highly unstable because of psychosocial barriers in their lives (Hser et al., 1998). Such psychosocial factors are critical components of how individuals get connected to drug treatment (DiClemente et al., 2004), and they may further impede pathways to treatment if such concerns are reinforced through discussions within drug using social networks.

These psychosocial concerns may be augmented by aspects unique to the drug treatment system in China. Beyond medicalized drug treatment modalities, treatment programs tied to the criminal justice system in China function punitively. In this regard, substantial differences exist between the voluntary substance abuse treatment programs managed by health departments and physicians, and the compulsory treatment programs administered by the criminal justice system (Tang and Hao, 2007), although considerable movement away from the punitive system has occurred over the past decade (Luo et al., 2014). A lack of clarity on differences between these systems may create confusion about treatment options for drug users who consider seeking help. It may also lead to negative perceptions of treatment that serve as barriers. The potential impact of such negative perceptions is significant. Substance abuse treatment in China has become more hospitable to drug users over the past two decades. For example, emphasis on relapse prevention and behavioral change has advanced, including the establishment of residential therapeutic communities (Tang & Hao, 2007), and these may shift the perceptions of drug users to enables more positive assessments of drug treatment. Regardless, poor perceptions of drug treatment programs remain considerable barriers to treatment within this population (see Luo et al., 2014 & Sun et al., 2014 for current discussions of the Chinese drug treatment system).

The literature also indicates that not all drug users perceive drug treatment in the same way. It remains important to assess how they are differentially affected by their social position. Factors such as gender, age, education, ethnicity, employment and marital status differentially affect both drug use and pathways out of drug use in myriad ways. Yet, the literature has not fully clarified how demographic factors influence barriers to drug treatment. For example, Hser et al. (1998) found no differences in treatment entry by gender, ethnicity, employment status, or marital status, although others have found such differences (Greenfield et al., 2007; Lundgren et al., 2001; Siegal et al., 2002). Beyond demographics, we must also consider how individual factors such as personal drug use and history of prior drug treatment shape barriers perceived by drug users. Research has shown that the extent of drug use was positively associated with treatment entry (Chitwood & Morningstar, 1985; Gyarmathy & Latkin, 2008). Studies have also demonstrated that prior history of drug treatment was positively associated with future entry into treatment (Davey et al., 2007; Schutz et al., 1994; Siegal et al., 2002). Thus, these personal factors influence how drug users perceive barriers to drug treatment.

To move this research domain forward, we evaluate psychosocial barriers to drug treatment among Chinese methamphetamine users. Rapp et al. (2006) introduced the Barriers to Treatment Inventory (BTI) for the assessment of barriers to treatment among drug users. Following this, Xu et al. (2007) used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the factorial structure of internal barriers of the BTI among a sample of American drug users. Their results extended the four domains of barriers identified by Rapp et al. (2006) – absence of a problem, negative social support, fear of treatment, privacy concerns – to include a fifth domain, the committed lifestyle as a barrier to drug treatment (Xu et al., 2007). We extend this work through the application of the BTI to assess internal barriers to treatment in among drug users in China, which assesses its utility for non-Western populations.

2. Methods

All participants completed a structured survey, which contained approximately 250 questions and was completed by participants in approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour. Participant enrollment occurred from June 2010 to January 2012. The survey captured a range of information from substance use to social and psychological factors to physical and mental health, including topics not under consideration in this paper. IRB approval was received from both universities.

2.1 Sampling

To recruit our sample, we employed Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS; Heckathorn, 1997; Wang et al, 2005; 2007; Abdul-Quader et al., 2006). To initiate the RDS process, we recruited 20 “seeds.” Upon enrollment, each seed was given 3 “coupons” coded with numeric digits linkable to them in addition to the incentive received for participation (150 Chinese Yuan/$23 USD). They were asked to encourage network members to be screened for participation. Each time a network member enrolled in the study and presented a coupon, the “seed” received an additional incentive (50 Chinese Yuan/$8 USD) for facilitating the network participation. A limitation of 3 coupons was used to reduce the likelihood of bias towards those with large networks (Heckathorn, 1997; Wang et al, 2005). Each recruit received the standard incentive for participation. The enrolled recruit also received three recruitment coupons and was offered the same incentives to encourage enrollment among network members. The process continued through successive waves to build momentum within the networks to foster participation. Analyses of the RDS cohort indicated the sample reached convergence.

2.2 Measures

Demographic information

The survey first gathered demographic information. Participants self-reported gender: female or male. They were asked their birth year, used to assess age. They self-reported whether they were Han Chinese or an ethnic minority. Employment was assessed: fulltime, part-time, student, or unemployed. Education was assessed: elementary school or less, middle school/some high school, high school diploma, some college, or college degree or greater. Marital status was reported as married, domestic partner, steady boyfriend/girlfriend, single, divorced, or widowed.

Substance use

Substance use measures generated information on drugs used, duration of use (in months), frequency of use, dose per use, and mode of administration. We assessed 9 major substances of abuse in China and also asked participants to self-report other substances they used. We assessed whether they had any history of drug treatment. The Short Inventory of Problems with Alcohol & Drugs (SIP-AD) was used to assess methamphetamine related problems (Blanchard et al., 2003) and the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory (CIDI) substance abuse module was tailored to assess symptoms of dependence on methamphetamine (Cottler et al., 1989).

Measures of internal barriers to drug treatment

We used the Barriers to Treatment Inventory (BTI; Rapp et al., 2006) to assess internal barriers to drug treatment. It is one of the most comprehensive and psychometrically sound measures currently available. The BTI scale was translated into Chinese using the back translation method and then pilot-tested with individuals in drug treatment prior to use in this study. Five domains of internal barriers [absence of problem (AP), negative social support (NSS), fear of treatment (FT), privacy concerns (PC), and committed life style (CLS)] to drug treatment were measured with 20 items. The participants were asked to indicate how much each type of barrier influenced their access to treatment services, with each item measured on a 5-point scale. The original Likert scales were treated as either numeric or categorical measures in our exploratory modeling, but the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model did not fit the data in either way because the measures were highly skewed. As such, the items were recoded as dichotomous measures (1-agree/strongly agree; 0- otherwise) in this study. The dichotomous measures are meaningful because the barrier items represent specific problems of accessing drug treatment programs.

2.3 Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study were: 1) methamphetamine use within the previous three months; 2) residence in Changsha; and 3) the capacity to volunteer for research participation. Subjects were excluded if they: 1) were enrolled in drug treatment; 2) were in prison/jail; 3) planned to move from Changsha within 6 months; 4) had a significant psychotic disorder (severe enough to prevent capacity to consent), or 5) displayed impairment by drug use at time of the assessment.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

The Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20), which is a non-parametric equivalent to Cronbach’s alpha, was used to evaluate the internal consistency of each subscale with dichotomous items (Fleming, Sanderson, Stokes & Walton, 1976; Ghiselli, Campbell & Zedeck, 1981; Cortina, 1993). A KR-20 coefficient ≥ 0.60 is considered to indicate that the measure is internally consistent (Allen et al. 2000). The measurement model of the internal barrier scale was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with dichotomous indicators. One subscale (i.e., committed lifestyle) that has only two items was removed from the model because of poor reliability, which led to poor model fit. One item Y12 (Treatment will add another stress to my life) was specified to be cross-loaded on both Fear of Treatment and Negative Social Support. No error covariance was specified in the measurement model for the purpose of model fit improvement.

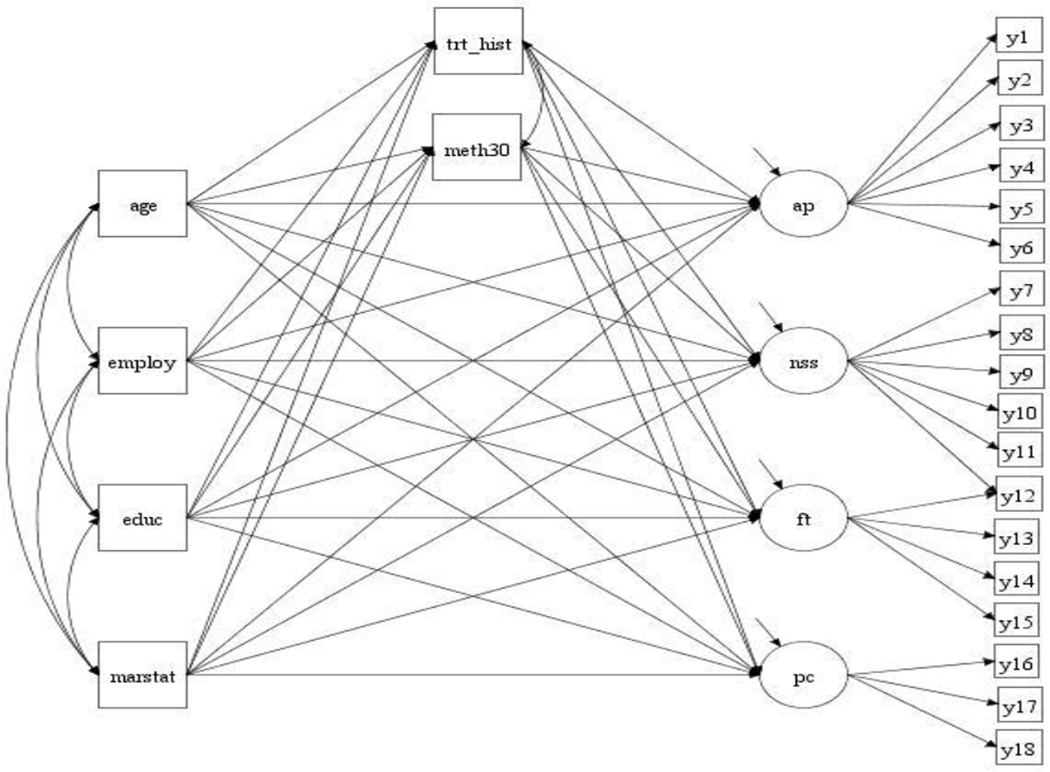

A Structural Equation Model (SEM; see Figure 1) was used to examine a) whether the internal barrier measures were associated with treatment history and frequent methamphetamine use (using more than 30 days in the past 3 months); and b) whether and how demographic characteristics, such as age, employment, education, and marital status, would influence the internal barriers. The direct effect, specific and total indirect effects, as well as total effect of each demographic factor on each subscale were examined. Gender was excluded from the SEM model because of too few females (n=39) in the sample, which is common in China as considerable gender disparities in drug use remain. With gender included in the model, model estimation was not normally ended because the weight matrix of some variables became noninvertible. Ethnicity was excluded with so few non-Han individuals (n=6).

Figure 1. Structural equation model.

Note: ap: Absence of problem; nss: Negative social support ; ft: Fear of treatment ; pc: Privacy concerns ; trt_hist: treatment history (1-ever being in drug treatment; 0-otherwise); meth30: frequency of meth use in the past 30 days; employ: employ status (1-employed; 0-otherwise); educ: education measured on a 6-point scale; marstat: marital status (1-married; 0-otherwise).

The model was estimated using the mean and variance-adjusted weighted least-squares (WLSMV) estimator, available in Mplus (Muthèn & Muthèn, 1998–2012). With WLSMV, Mplus uses the Probit function to link the observed binary indicators to their underlying latent variables/factors. Correlations between the latent continuous response variables y*s (i.e., tetrachoric correlations), rather than the variance/covariance of the observed indicators, were analyzed. The factor loading of each item is the Probit slope coefficients of regressing the items on their underlying factor. The model is specified in Figure 1.

3. Results

Demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The sample was primarily male (87.1%) and Han Chinese (98%). Over one-third worked full-time (38.6%) with an additional quarter (27.7%) employed part-time. The remaining subjects were primarily unemployed (31.4%) with few full-time students (2.3%). A majority of the sample had less than a high school diploma (59.7%), 24.8% earned a high school diploma, 10.9% experienced some college, and 4.6% earned a college degree. A majority (55.1%) reported an income of over 50,000 Yuan. Over two-fifths of the sample reported being married (42.6%). The sample reported problems related to methamphetamine use as well as indications of dependency. Almost 9 out of 10 (88.4%) reported at least one problem associated with their methamphetamine use, and the sample as a whole reported an average of 6.74 problems (median = 7) based upon the SIP-AD. Additionally, 68% of the sample met cutoff criteria for indications of dependence on the CIDI, and the average score was 6.34. Collectively, these measures indicate that this is a population experiencing considerable problem use or dependence and may benefit from treatment intervention.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, n = 303

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 29.9 (7.62) |

| % (n) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 87.1% (264) |

| Female | 12.9% (39) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Han Chinese | 98.0% (297) |

| Non-Han Ethnic Minority | 2.0% (6) |

| Education | |

| Elementary or less | 12.2% (37) |

| Middle School/some High School | 47.5% (144) |

| High School Diploma | 24.8% (75) |

| Some College | 10.9% (33) |

| College Degree or greater | 4.6% (14) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 38.6% (117) |

| Part-time | 27.7% (84) |

| Student | 2.3% (7) |

| Unemployed | 31.4% (95) |

| Income | |

| < 10,000 Yuan | 13.5% (41) |

| 10,000–29,999 | 12.2% (37) |

| 30,000–49,999 | 15.9% (48) |

| 50,000 Yuan or greater | 55.1% (167) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Legally married | 42.6% (129) |

| Domestic partner | 4.3% (13) |

| Boy/girlfriend | 24.8% (75) |

| Single | 24.4% (74) |

| Divorced | 3.6% (11) |

| Widowed | 0.3% (1) |

| Methamphetamine Problems | |

| At least one problem on SIP_AD | 88.4% (368) |

| Mean # of problems reported | 6.74 (median = 7) |

| Meet dependence cutoff on CIDI | 68.0% (206) |

| Mean CIDI score | 6.34 (median = 6) |

The results of testing internal consistency/reliability of the barrier scales are shown in Table 2. The KR-20 coefficients are high for three scales: 0.81 for AP, and 0.77 for NSS, and 0.83 for FT, while they are only 0.38 for PC, and 0.12 for CLS, respectively. While excluding the scale of CLS from further analysis, the PC scale was included in the structural equation model because once the item Y12 (Treatment will add another stress to my life) was cross loaded on Negative Social Support, and the model fit the data very well.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of drug treatment barriers (N=303)

| Item | N* (%) |

|---|---|

| Absence of Problem | (KR-20=0.81) |

| Y1 | 121 (39.93) |

| Y2 | 148 (48.84) |

| Y3 | 44 (14.52) |

| Y4 | 136 (44.88) |

| Y5 | 187 (61.72) |

| Y6 | 170 (56.11) |

| Negative Social Support | (KR-20=0.77) |

| Y7 | 73 (24.09) |

| Y8 | 32 (10.561) |

| Y9 | 40 (13.20) |

| Y10 | 94 (31.02) |

| Y11 | 129 (42.57) |

| Fear of Treatment | (KR-20=0.38)& |

| Y12 | 94 (31.02) |

| Y13 | 18 (5.94) |

| Y14 | 11 (3.63) |

| Y15 | 17 (5.61) |

| Privacy Concerns | (KR-20=0.83) |

| Y16 | 41 (13.53) |

| Y17 | 46 (15.18) |

| Y18 | 60 (19.80) |

| Committed Life Style | (KR-20=0.12) |

| Y19 | 1 (0.33) |

| Y20 | 31 (10.23) |

Note.

: Number of “1”s (item was coded 1 if the response was “agree” or “strongly agree;” otherwise coded 0).

KR-20: The Kuder Richardson Coefficient of reliability, which is non-parametric equivalent to Cronbach’s α.

: KR-20 increased to 0.58 whenY12was excluded from the indicators of Fear of Treatment.

Our CFA results show that this item is cross-loaded on Negative Social Support as well.

Y1: I do not think I have a problem with drugs

Y2: No one has told me I have a problem with drugs

Y3: My drug use is not causing any problems

Y4: I do not think treatment will make my life better

Y5: I can handle my drug use on my own

Y6: I do not think I need treatment

Y7: I will lose my friends if I go to treatment

Y8: Friends tell me not to go to treatment

Y9: People will think badly of me if I go to treatment

Y10: Someone in family doesn't want me to go to treatment

Y11: My family will be embarrassed or ashamed if I go to treatment

Y12: Treatment will add another stress to my life

Y13: I am afraid of what might happen in treatment

Y14: I am afraid of the people I might see in treatment

Y15: I am too embarrassed or ashamed to go to treatment

Y16: I don't like to talk in groups

Y17: I hate being asked personal questions

Y18: I don't like to talk about my personal life with other people

Y19: I cannot live without drugs

Y20. Using drugs is a way of life for me

Selected results of the SEM model are shown in Tables 3 and 4. A range of model fit indices show that the model fits the data well: CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.04 (90% C.I.: 0.03, 0.05), Close-Fit Test P-value=0.955, and WRMR=0.98 (see the bottom of Table 3). The factor loadings are reported in Table 3. One item (Y12) is cross-loaded on both FT and NSS scales with acceptable factor loadings (0.35, p=0.001 and 0.63, p<0.0001, respectively). The remaining items are all appropriately loaded on their theoretical underlying factors with factor loadings from 0.48 to 0.97.

Table 3.

Selected results of the SEM model

| Item | Absence of Problem | Negative Social Support |

Fear of Treatment | Privacy Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | ||||

| Y1 | 0.88 | |||

| Y2 | 0.83 | |||

| Y3 | 0.48 | |||

| Y4 | 0.81 | |||

| Y5 | 0.90 | |||

| Y6 | 0.96 | |||

| Y7 | 0.89 | |||

| Y8 | 0.56 | |||

| Y9 | 0.90 | |||

| Y10 | 0.94 | |||

| Y11 | 0.93 | |||

| Y12 | 0.63 | 0.35 | ||

| Y13 | 0.91 | |||

| Y14 | 0.97 | |||

| Y15 | 0.77 | |||

| Y16 | 0.88 | |||

| Y17 | 0.96 | |||

| Y18 | 0.97 | |||

Model Fit CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.04 (90% C.I.: 0.03, 0.05), Close-Fit Test P-value=0.955 WRMR=0.98

Table 4.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of demographics on internal barriers to drug treatment

| Variable | Effect | Meth Use | Trt History | Absence of Problem |

Negative Social Support |

Fear of Treatment |

Privacy Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meth Use1 | Direct Effect | −0.25* | −0.30* | −0.10 | 0.09 | ||

| Trt History2 | Direct Effect | −0.68* | −0.65* | 0.08 | −0.01 | ||

| Direct Effect | 0.05 | 0.28* | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.26 | −0.14 | |

| Indirect Effect via Meth Use | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Age | Indirect Effect via Trt History | −0.19* | −0.18* | 0.02 | −0.00 | ||

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.20* | −0.20* | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Total Effect | −0.07 | −0.14 | −0.25 | −0.13 | |||

| Direct Effect | −0.18* | −0.194* | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.00 | −0.02 | |

| Indirect Effect via Meth Use | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.02 | |||

| Employment | Indirect Effect via Trt History | 0.13* | 0.12* | −0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.17* | 0.17* | 0.00 | −0.02 | |||

| Total Effect | 0.19* | 0.22* | 0.00 | −0.40 | |||

| Direct Effect | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.02 | |

| Indirect Effect via Meth Use | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Marital Status | Indirect Effect via Trt History | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.00 | ||

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |||

| Total Effect | −0.13 | 0.04 | −0.8 | 0.02 | |||

| R2 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

Note.

: Statistically significant at 0.05 level

: Used methamphetamine more than 30 times in the past 30 days.

: Ever being in drug treatment program.

Path coefficients are reported in Table 4. Both frequency of methamphetamine use and history of being in drug treatment have inverse effects on the subscales of AP and NSS, but no effects on FT and PC scales. Thus, people who more frequently used methamphetamine were less likely to report both absence of drug problem (β =−0.25, p= 0.006) and negative social support (β =−0.30, p= 0.003). The corresponding coefficients for history of being in drug treatment are β =−0.68 (p<0.001) and β =−0.65 (p<0.001), respectively.

Age has no direct effect on the barrier scales, but has a significant positive effect on drug treatment history. As could be expected, older people were more likely to have experienced drug treatment (β =0.28, p= 0.002). As a result, age has a significant indirect effect via drug treatment history on AP (β =−0.19, p= 0.007) and NSS (β =−0.18, p= 0.012), respectively. However, the total age effect on the two barrier scales are not statistically significant because the positive direct effects (β =0.14, p= 0.064 for AP; β =0.06, p= 0.456 for NSS) and negative indirect effects canceled each other out.

Employment status has no direct effect on any of the barrier scales, but it significantly affects drug treatment history (β =−0.19, p= 0.017) and frequent methamphetamine use (β =- 0.18, p= 0.022). Via drug treatment history, employment has significant indirect effects on AP (β =0.13, p= 0.034) and NSS (β =0.12, p= 0.035). Its total effects on these two barrier scales are also statistically significant (β =0.19, p= 0.009 for AP; β =0.22, p= 0.011 for NSS). Education’s direct and indirect effects on the barrier scales are not statistically significant. However, its total effect on NSS is significant (β =0.16, p= 0.024). Marital status has no effect on the barrier scales. The explained variation (R2) in the Probit indices are 0.59 for AP, 0.63 for NSS, and 0.12 for FT. However, not much variation in PC is explained (R2=0.05).

4. Discussion

The results provide an assessment of the psychosocial barriers to treatment among Chinese methamphetamine users. Overall, we found four primary factors of internal barriers to drug treatment – absence of problem (AP), negative social support (NSS), fear of treatment (FT), and privacy concerns (PC) – to fit the data well. In this regard, we provide further evidence on the dimensionality of the BTI. We find that the factors comprising the dimensions of internal barriers to drug treatment map to dimensions proposed by Rapp et al (2006) in their original assessment. Unlike the assessment by Xu et al. (2007), we do not find that the factor of committed lifestyle (CLS) fits well within the model. Overall, the findings provide support for the primary four-factor design of the measure as described by the original developers, which lends support for the use of this measure in non-Western populations of drug users.

With respect to factors associated with the dimensions of internal barriers to treatment, demographic factors did not have direct effects on psychosocial barriers to drug treatment. Rather, we mostly find that demographic factors, notably age and employment status, indirectly influence barriers to treatment. Frequency of methamphetamine use and drug treatment history are directly associated with the AP and NSS dimensions of the BTI, and it is through these pathways that factors such as age and employment status shape barriers to treatment. Factors such as drug use frequency and drug treatment history have been previously shown to impact entry into drug treatment (Davey et al., 2007; Gyarmathy & Latkin, 2008; Schutz et al., 1994; Siegal et al., 2002). In this regard, Chinese drug users report factors that influence perceived accessibility of drug treatment in a way that coheres with some findings on drug users in Western settings. These remain points of concern for clinicians and public health professionals.

This paper has several implications for policy and practice. First, the paper identifies that methamphetamine users in China are experiencing perceived barriers to drug treatment access. As such, they represent a population in need of further attention from health care professionals, and health departments should make efforts to engage these users. In particular, perceived absence of a problem and negative social support are most influenced by the personal domains of drug users’ lives. Given methamphetamine’s relatively new position in China’s drug scenes, users may not recognize the problems associated with dependence relative to substances with long histories of use, such as heroin and opium. They may also fear that others may not understand an addiction to methamphetamine. Recent studies suggest that methamphetamine users do not regularly identify addiction as a risk from use (Kelly et al., 2014). Chinese officials may consider expanding the scope of resources made available for clinicians and treatment professionals to engage this emerging population of methamphetamine users.

4.1 Limitations

Although our findings provide important information about psychosocial barriers to drug treatment in China, we must consider some limitations. First, the self-report survey may lead to certain biases, particularly those related to social desirability. This remains a concern for many studies. The cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to draw causal inferences, although the independent variables studied are temporal precedents to the perceptions captured by the BTI. Additionally, the sample of methamphetamine users may not generalize to all drug users. Finally, the study was conducted in a provincial capital city in central China, and may not represent the barriers to treatment in other regions within China. Despite these limitations, the results reported provide important information on the perception of psychosocial barriers to treatment among methamphetamine users in China.

4.2 Conclusions

Our analyses present interesting findings on perceived psychosocial barriers among drug users in China. First, we provide further evidence for the utility of the BTI scale as well as the ability to utilize it with non-Western drug using populations. Second, we confirm work by Rapp and colleagues (2006) that the BTI provides a four dimensional assessment of internal barriers to drug treatment. Finally, we find that demographic features are indirectly associated with certain internal barrier factors via the frequency of drug use and past history of drug treatment. Collectively, our findings indicate that perceived absence of a problem and negative social support are barriers most influenced by the personal domains of drug users’ lives. Efforts to engage drug users in China about drug treatment options may consider how barriers are differentially perceived by those with differing use patterns and experiences with treatment in order to effectively reach this population.

Highlights.

-

-

Four primary internal barriers to drug treatment exist in China

-

-

Age and employment status indirectly influence internal barriers to treatment

-

-

Frequency of use and drug treatment history are directly associated with barriers

-

-

Chinese drug users differentially experience barriers to treatment

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of other members of the project team, especially the staff who conducted the surveys.

Role of Funding Source : This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA026772, Brian C Kelly, P.I.). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of this study and the views expressed in this paper do not expressly reflect the views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or any other governmental agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

-

-Brian Kelly is the P.I. of the study and is responsible for the conceptualization of the study design and writing the paper.

-

-Tieqiao Liu is a Co-Investigator of the study and study site director. He contributed to the study design and implementation and also contributed to the writing of the paper.

-

-Guanbai Zhang contributed to the sampling of human subjects and survey staff direction and oversight.

-

-Wei Hao is a Co-Investigator of the study and contributed to its design and implementation

-

-Jichuan Wang is a Co-Investigator of the study, contributed to its design and implementation, and conducted the statistical analyses for the paper.

Conflict of Interest : The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, Bramson H, Nemeth C, Sabin K, Gallagher K, DesJarlais DC. Effectiveness of Respondent Driven Sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: Findings from a pilot study. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:459–476. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RM, Abdulwadud OA, Jones MP, Abramson M, Walters H. A reliable and valid asthma general knowledge questionnaire useful in the training of asthma educators. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;39:237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel PK, Ellison AA, Jansky HK, Oldak R. Barriers to enrollment in drug abuse treatment and suggestions for reducing them : Opinions of drug injecting street outreach clients and other system stakeholders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:129–153. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DD, Morningstar PC. Factors which differentiate cocaine users in treatment from nontreatment users. International Journal of the Addictions. 1985;20:49–459. doi: 10.3109/10826088509044925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina JM. What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of a test. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S, Toneatte T. Barriers to treatment: Why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18:347–353. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey MA, Latkin CA, Hua W, Tobin K, Strathdee S. Individual and social network factors that predict entry into drug treatment. American Journal of Addictions. 2007;16:38–45. doi: 10.1080/10601330601080057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. American Journal of Addiction. 2004;13:103–119. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PR, Sanderson PH, Stokes JF, Walton HJ. Examinations in Medicine. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselli EE, Campbell JP, Zedeck S. Measurement Theory for the Behavioral Sciences. San Francisco, CA: W H Freeman; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmathy VA, Latkin CA. Individual and social factors associated with participation in treatment programs for drug users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:1865–1881. doi: 10.1080/10826080802293038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Maglione M, Polinsky ML, Anglin MD. Predicting drug treatment entry among treatment seeking individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:213–230. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Zhang L, Liu J. Drug problems in contemporary China: A profile of Chinese drug users in a metropolitan area. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2011;22:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Liu T, Yang XY, Zhang G, Hao W, Wang J. Perceived risk of methamphetamine among Chinese methamphetamine users. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.007. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren LM, Amodeo M, Ferguson F, Davis K. Racial and ethnic differences in drug treatment entry of injection drug users in Massachusetts. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Wang J, Li Y, Wang X, Tan L, Deng Q, Thakoor JP, Hao W. Stigmatization of people with drug dependence in China: A community-based study in Hunan province. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2014;134:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthèn L, Muthèn B. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthèn & Muthèn; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nummally J. Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Qi C, Kelly BC, Liu T, Liao Y, Hao W, Wang J. A latent class analysis of external barriers to drug treatment in China. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp RC, Xu J, Carr CA, Lane DT, Wang J, Carlson RG. Treatment barriers identified by substance abusers assessed at a centralized intake unit. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz CG, Rapiti E, Vlahov D, Anthony JC. Suspected determinants of enrollment into detoxification and methadone maintenance treatment among injecting drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;36:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal HA, Falck RS, Wang J, Carlson RG. Predictors of Drug Abuse Treatment Entry among Crack-Cocaine Smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 68:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Liu Y, Fang Y, Xu G, Zhai H, Lu L. Traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of opiate addiction. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2006;27:1303–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HQ, Chen HM, Yang FD, Lu L, Kosten TR. Epidemiological trends and the advances of treatments of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) in China. American Journal on Addictions, Early View. 2014 doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YL, Hao W. Improving drug addiction treatment in China. Addiction. 2007;102:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drug Report. Vienna, Austria: UNODC; 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Carlson RG, Falck RS, Siegal HA, Rahman A, Li L. Respondent Driven Sampling to recruit MDMA users: A methodological assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Falck RS, Li L, Rahman A, Carlson RG. Respondent-Driven Sampling in the recruitment of illicit stimulant drug users in a rural setting: Findings and technical issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:924–937. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang J, Rapp RC, Carlson RG. The multidimensional structure of internal barriers to substance abuse treatment and its invariance across gender, ethnicity, and age. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37:321–340. doi: 10.1177/002204260703700205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. Tokyo Japan: 2008. Feb, Drug data collection in China. Presentation at the 4th International Forum on the Control of Precursors for ATS. 2008. [Google Scholar]