Abstract

A simple method for the study of sugar-nucleotide-dependent multienzyme cascades is highlighted where the use of selectively 13C-labeled sugar nucleotides and inverse 13C detection NMR offers fast, direct detection and quantification of reactants and products and circumvents the need for chromatographic separation. The utility of the method has been demonstrated by characterizing four previously uncharacterized sugar nucleotide biosynthetic enzymes involved in calicheamicin biosynthesis.

Sugars are critical in cells where they play important roles in energy metabolism, maintenance of cell integrity, molecular recognition, and signaling.1 For many small molecule-based glycoconjugates, the nature of the sugar dramatically influences the properties of the metabolite to which it is attached,2 prompting the development of chemoenzymatic strategies to manipulate small molecule pharmacology via differential glycosylation.3 In nature, many carbohydrate maturation and attachment processes are mediated via sugar-nucleotide-dependent multienzyme cascades (Scheme S1 in Supporting Information).3b,3c These sugar-nucleotide-dependent pathways diverge from a relatively small set of common progenitors and share a number of conceptual and strategic similarities. Yet, the biochemical study of the catalysts involved often remains a challenging endeavor (Scheme S1 in Supporting Information). The development and implementation of simple, broadly applicable assay strategies for divergent sugar-nucleotide-dependent multienzyme transformations is expected to facilitate such studies.

Over the past two decades several sugar-nucleotide-dependent biosynthetic enzymes have been characterized.3,4 In most cases, these studies have relied upon discontinuous HPLC-based assays that often (i) require strong ion-pairing agents/salts incompatible with mass spectrometry; (ii) lack sufficient resolution to resolve many reactants/products/cofactors typically found within multienzyme cascades; and (iii) operate on a time scale unsuitable for short-lived or unstable intermediates. While NMR offers the advantage of real-time detection of reactants/products without tedious chromatography, the studies to date (which have relied upon direct detection of 1H or 13C and/or indirect detection of 13C and 31P mostly from the natural abundance)5 still often suffer from a lack of resolution in the context of complex cofactor/reagent/product-containing multienzyme reactions. To extend upon the potential advantages of NMR within this context, herein we describe an efficient NMR-based method that combines the sensitivity of inverse detection two-dimensional (2D)-NMR with the convenient preparation and direct use of NDP-α-d-[U-13C]hexose-based substrates. Distinct from prior multienzyme preparations of NDP-α-d-[U-13C]glucose,4 an enabling feature of this work is the single-step synthesis of this key reagent from 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl-α-d-[U-13C]glucose (4 in Scheme 1) catalyzed by engineered macrolide glycosyltransferase OleD variant TDP16.6 Cumulatively, this study presents a user-friendly rapid and general method for sugar nucleotide characterization in complex mixtures and also provides new biochemical annotation for a set of four previously uncharacterized sugar-nucleotide-dependent enzymes involved in calicheamicin biosynthesis: a 4,6-dehydratase (CalS3), a 4-aminotransferase (CalS13),7 a 3,5-epimerase (CalS1), and a 4-ketoreductase (CalS2).8 Furthermore, the application of the method for rate determination (OleD TDP16 and CalS3)6 and potential strategies to address stereospecificity (CalS13 versus WecE9) are briefly highlighted.

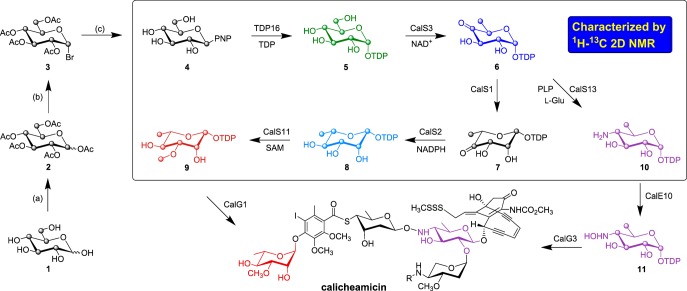

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl-β-d-[U-13C]glucose and Proposed Biosynthetic Pathway of TDP-4-Hydroxyamino-6-deoxy-glucose and TDP-3-Methoxy-rhamnose en Route to Calicheamicin.

(a) Ac2O pyridine; (b) HBr, AcOH/DCM, 0 °C, 2 h; (c) 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol, TBABr, DCM/NaOH (1:1), rt, 18 h; NaOMe, MeOH, rt, 12 h; d-[U-13C]glucose, 1; penta-O-acetyl-d-[U-13C]glucose, 2; 1-bromo-tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-[U-13C]glucose, 3; 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl-β-d-[U-13C]glucose, 4; TDP-α-d-[U-13C]glucose, 5; TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-d-[U-13C]glucose, 6; TDP-4-keto-β-l-[U-13C]rhamnose, 7; TDP-β-l-[U-13C]rhamnose, 8; TDP-3-methoxy-β-l-[U-13C]rhamnose, 9; TDP-4-amino-6-deoxy-α-d-[U-13C]glucose, 10; TDP-4-hydroxyamino-6-deoxy-α-d-[U-13C]glucose, 11.

For this study, genes encoding a representative set of previously uncharacterized calicheamicin aryltetrasaccharide biosynthetic enzymes (annotated based on BLAST results as TDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratase CalS3, TDP-glucose-3,5-epimerase CalS1, TDP-glucose-4-ketoreductase, CalS2, and TDP-glucose-4-aminotransferase CalS13; Scheme 1)8 were amplified from Micromonospora echinospora genomic template DNA using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subsequently cloned into a pET28a vector. The resulting constructs were used to transform the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells to provide overproduction strains of the corresponding target enzymes as N-terminal His6-fusion proteins to afford rapid purification via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (see Supporting Information).

An enabling feature of this work is the single-step OleD TDP16-catalyzed formation of 5 from 4 (Scheme 1), generated in three simple steps (30% overall yield) from 1.6 The in situ NMR reactions were conducted in a 5 mm NMR tube at 25 °C using standard assay conditions (see Supporting Information) in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 10–20% D2O, pH 7.5. For all reactions, the NMR probe was tuned and shimmed with an NMR tube containing the entire reaction mixture in the absence of enzyme and reactions were subsequently initiated via the addition of enzyme, before the acquisition of a series of 2D-1H–13C HSQC (referred just as HSQC henceforth) spectra. Reaction progress was monitored by the appearance of new product-based resonances and consequent decrease in the intensity of substrate signals in the HSQC spectra over time. For rate measurements, a total of 40–80 HSQC spectra were collected, depending on the speed of the reaction. At the completion or near completion of each enzyme reaction, 2D 1H–13C planes of HCCH-TOCSY and/or HCCH-COSY (see Supporting Information) were collected to assist with the resonance assignment. The product formation of all the reactions was also subsequently confirmed via HRMS analysis (see Supporting Information).

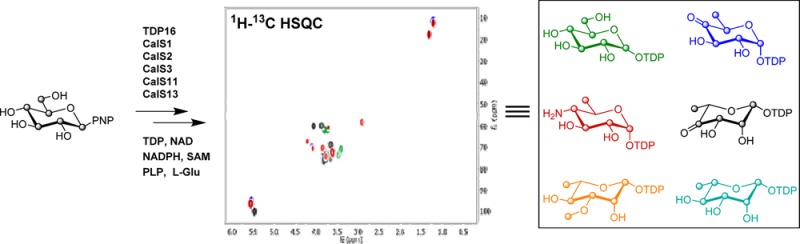

While the culminating CalE10-catalyzed N-oxidation of aminosugar nucleotide 10 en route to calicheamicin (Scheme 1) has been characterized,11 the putative steps/enzymes responsible for the formation of 10 remained uncharacterized. We used 4 as the initiating substrate, bypassing the native thymidylyltransferase-catalyzed (CalS7)8 formation of 4. To confirm the putative steps/enzymes responsible for the formation of 10 in the calicheamicin pathway, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.5 μM of TDP16 to a reaction mixture containing 4 and 0.1 equiv excess of TDP with respect to 4 (HSQC black resonances, Figure 1A) to drive the equilibrium toward the desired 13C-labeled sugar nucleotide 5 (HSQC green resonances, Figure 1A). Upon reaction completion based upon NMR, 0.2 mM NAD+ and 11.5 μM of CalS3 were added to the reaction mixture and the formation of 6 (HSQC blue resonances, Figure 1A) was subsequently monitored. Following the completion of the CalS3 reaction, 200 μM PLP, 10 mM l-glutamic acid, and 14 μM of CalS13 were added to the reaction and monitored for the appearance of signals consistent with the formation of 10 (HSQC purple resonances reflecting a mixture of 6 and 10, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Overlay of 2D-1H–13C-HSQC spectra of TDP16, CalS3 and CalS13 reactions. (B) Overlay of 2D-1H–13C-HSQC spectra of 6 (HSQC with blue signals), CalS1, CalS2, and CalS11 reactions. Colors correlate to the products in Scheme 1.

In the TDP-methoxy-rhamnose (9, Scheme 1) pathway of calicheamicin, CalS11 has been established as the TDP-rhamnose (8) C3-O-methyltransferase (O-MT) and is the only natural product sugar O-MT studied thus far that acts on the sugar nucleotide substrate prior to a subsequent glycosyltransfer reaction.10 While the biosynthesis of 8 has been extensively studied in a range of systems,12 the formation of 8 in the context of calicheamicin has not been characterized. To characterize the enzymes corresponding to the calicheamicin TDP-methoxy-rhamnose pathway, 6 (HSQC blue resonances, Figure 1B) was generated as described in the previous paragraph and 9.5 μM of CalS1 (the putative 3,5-epimerase) was added to the reaction mixture. Interestingly, no change in the HSQC spectra was observed in the presence of CalS1, suggesting the reaction equilibrium to favor reactants or, as proposed by Melo and Glaser,13 the 3,5-epimerase and 4-keto reductase to require the formation of a functional complex. Consistent with this, the addition of 6.2 μM of CalS2 and 5 mM NADPH after ∼3 h led to the appearance of new signals indicative of formation of 8 (HSQC light blue resonances reflecting a mixture of 6 and 8, Figure 1B). Importantly, the corresponding control lacking CalS1 failed to provide 8. Subsequent addition of 2 mM [U-13C]CH3-S-adenosyl-l-methionine10 and 9 μM CalS11 to the CalS2 reaction resulted in the formation of 9 (HSQC red resonances, Figure 1B).

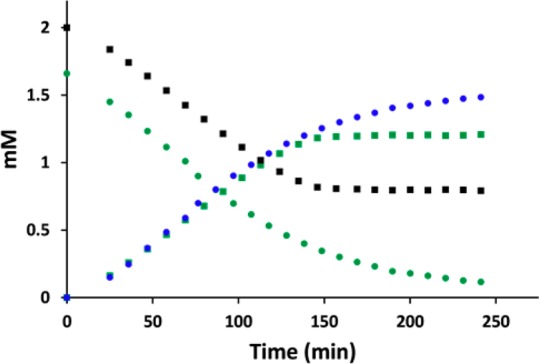

To assess the utility of this method for rate determination, a series of HSQC spectra for two model reactions (TDP16 and CalS3) were recorded in triplicate over several hours. Based upon a calibration curve obtained from integrating the anomeric signals in the HSQC spectra (using NMRPipe software14) of standards 4 and 5 (Figure S2 in Supporting Information), the concentration of the corresponding reaction product/substrate in the spectra was plotted against reaction time and the corresponding rate, as reflected by the slope, determined by linear regression. Interestingly, the rate of TDP16 measured by this method (15.2 ± 1.2 min–1, Figure 2) was consistent with previously reported values (25.6 ± 0.5 min–1)6 while the rate determined for CalS3 (0.84 ± 0.03 min–1, Figure 2) is similar to that of other TDP-Glc 4,6-dehydratases from secondary metabolite producing strains (ranging from 1.5 to 16.4 min–1).15

Figure 2.

Progress of TDP16 (square) and CalS3 (circle) reactions. Colors correlate to the reactants/products in Scheme 1.

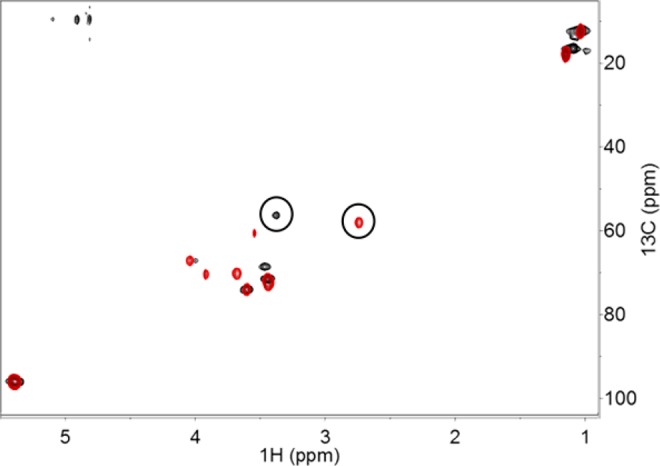

To explore the stereospecificity of CalS13, two model transaminase reactions were examined which differ solely by their stereospecificity of amino transfer. Specifically, starting from 6, the calicheamicin CalS13 is anticipated to provide a C4 (S) configuration while the E-coli WecE is known to provide C4 (R).9 Comparison of the H4′ chemical shift values of CalS13 (2.76 ppm) and WecE (3.44 ppm) products (circled in Figure 3) with previously reported data are consistent with the expected stereospecificities of amino transfer,9 suggesting this method to offer access to stereochemical information if the chemical shift information on at least one stereoisomer is available. While the method presented suggests broad utility, delineation of reaction stereospecificity for unknown molecules remains dependent upon the ability to obtain 1H–1H coupling constants.

Figure 3.

Overlay of 2D-1H–13C-HSQC spectra of CalS13 (red) and WecE (black) reactions. The C4′–H4′ correlations corresponding to CalS13 and WecE products are circled.

In summary, we have established a simple in situ NMR-based method to follow sugar-nucleotide-dependent multienzyme cascades in real time. The method is highly sensitive, affording simultaneous detection of all suitably labeled reactants, intermediates, and products available in quantities of ≥25 μg of compound and can be applied to measure kinetic parameters. As such, the method circumvents a major liability of prior methods, namely the difficulty of detecting short-lived intermediates/products. In addition, the commercial availability of additional [U-13C]sugar precursors along with the recent engineering of OleD variants to accommodate ADP, CDP, GDP, TDP, or UDP and a range of novel sugars suggests the potential for broad applicability.6,16

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH RO1 CA84374 (JST), NIH R37 AI52218 (JST), NCATS (UL1TR000117) and made use of the UW NMR FAM [supported in part by the NIH (P41RR02301, P41GM10399, RR02781, RR08438), University of Wisconsin, NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), DOE, and USDA].

Supporting Information Available

This includes general methods, overproduction and purification of enzymes, enzyme reactions, NMR and HRMS data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

∥ Glycom A/S, Denmark.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The authors report competing interests. J.S.T. is a co-founder of Centrose (Madison, WI).

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Kilcoyne M.; Joshi L. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2007, 5, 186–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kren V.; Rezanka T. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 858–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wrodnigg T. M.; Sprenger F. K. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2004, 4, 437–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kolarich D.; Lepenies B.; Seeberger P. H. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tiwari V. K.; Mishra R. C.; Sharma A.; Tripathi R. P. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1497–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Cipolla L.; Peri F. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Butler M. S. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 2141–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Weymouth-Wilson A. C. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997, 14, 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c La Ferla B.; Airoldi C.; Zona C.; Orsato A.; Cardona F.; Merlo S.; Sironi E.; D’Orazio G.; Nicotra F. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 630–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Thorson J. S. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1811–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Thibodeaux C. J.; Melancon C. E.; Liu H. W. Nature 2007, 446, 1008–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Thibodeaux C. J.; Melancon C. E. III; Liu H. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9814–9859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Cipolla L.; Araújo A. C.; Bini D.; Gabrielli L.; Russo L.; Shaikh N. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2010, 5, 721–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Oh T. J.; Mo S. J.; Yoon Y. J.; Sohng J. K. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 1909–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Blanchard S.; Thorson J. S. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006, 10, 263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yu B.; Sun J.; Yang X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1227–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a White-Phillip J.; Thibodeaux C. J.; Liu H. W. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 459, 521–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b He X. M.; Liu H. W. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 701–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Singh S.; Phillips G. N. Jr.; Thorson J. S. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1201–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lin C. I.; McCarty R. M.; Liu H. W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4377–4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Eixelsberger T.; Brecker L.; Nidetzky B. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 356, 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gasmi-Seabrook G. M.; Marshall C. B.; Cheung M.; Kim B.; Wang F.; Jang Y. J.; Mak T. W.; Stambolic V.; Ikura M. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 5137–5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jiang Y.; McKinnon T.; Varatharajan J.; Glushka J.; Prestegard J. H.; Sornborger A. T.; Schüttler H. B.; Bar-Peled M. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 2318–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Keshari K. R.; Wilson D. M.; Chen A. P.; Bok R.; Larson P. E.; Hu S.; Van Criekinge M.; Macdonald J. M.; Vigneron D. B.; Kurhanewicz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 17591–17596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Guyett P.; Glushka J.; Gu X.; Bar-Peled M. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1072–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Furtig B.; Richter C.; Schell P.; Wenter P.; Pitsch S.; Schwalbe H. RNA Biol. 2008, 5, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Mesnard F.; Ratcliffe R. G. Photosynth. Res. 2005, 83, 163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Weber H.; Brecker L. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000, 11, 572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Wang Z. Y.; Luo S.; Sato K.; Kobayashi M.; Nozawa T. Anal. Biochem. 1998, 257, 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Nakajima N.; Nakamura K.; Esaki N.; Tanaka H.; Soda K. J. Biochem. 1989, 106, 515–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Esaki N.; Shimoi H.; Nakajima N.; Ohshima T.; Tanaka H.; Soda K. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 9750–9752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Vandenberg J. I.; Kuchel P. W.; King G. F. Anal. Biochem. 1986, 155, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Cournoyer W. J.; Thorson J. S. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.; Ahlert J.; Xue Y.; Thorson J. S.; Sherman D. H.; Liu H. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9881–9882. [Google Scholar]

- a Ahlert J.; Shepard E.; Lomovskaya N.; Zazopoulos E.; Staffa A.; Bachmann B. O.; Huang K.; Fonstein L.; Czisny A.; Whitwam R. E.; Farnet C. M.; Thorson J. S. Science 2002, 297, 1173–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang C.; Griffith B. R.; Fu Q.; Albermann C.; Fu X.; Lee I. K.; Li L.; Thorson J. S. Science 2006, 313, 1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang C.; Bitto E.; Goff R. D.; Singh S.; Bingman C. A.; Griffith B. R.; Albermann C.; Phillips G. N. Jr.; Thorson J. S. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 842–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhao L.; Yeung B. S.; Liu H. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 7909–7910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hwang B. Y.; Lee H. J.; Yang Y. H.; Joo H. S.; Kim B. G. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Chang A.; Helmich K. E.; Bingman C. A.; Wrobel R. L.; Beebe E. T.; Makino S.; Aceti D. J.; Dyer K.; Hura G. L.; Sunkara M.; Morris A. J.; Phillips G. N. Jr.; Thorson J. S. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1632–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Johnson H. D.; Thorson J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17662–17663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Timmons S. C.; Thorson J. S. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Naismith J. H. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004, 32, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Naismith J. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Melo A.; Glaser L. J. Biol. Chem. 1968, 243, 1475–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Graninger M.; Nidetzky B.; Heinrichs D. E.; Whitfield C.; Messner P. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 25069–25077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F.; Grzesiek S.; Vuister G. W.; Zhu G.; Pfeifer J.; Bax A. J. Biomol. NMR 1995, 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Matern H.; Brillinger G. U.; Pape H. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1973, 88, 37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vara J. A.; Hutchinson C. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 14992–14995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Thompson M. W.; Strohl W. R.; Floss H. G. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1992, 138, 779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Singh S.; Zhou M.; Thorson J. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 7648–7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang J.; Singh S.; Hughes R. R.; Zhou M.; Sunkara M.; Morris A. J.; Thorson J. S. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.