Abstract

A new annulation strategy for the synthesis of trans-bicyclic sulfamides is described. The Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions of 2-allyl and cis-2,5-diallyl pyrrolidinyl sulfamides with aryl and alkenyl triflates afford the fused bicyclic compounds in good yields and with good diastereoselectivity (up to 13:1 dr). Importantly, by employing reaction conditions that favor an anti-aminopalladation mechanism, the relative stereochemistry between the C3 and C4a stereocenters of the products is reversed relative to related Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions that proceed via syn-aminopalladation.

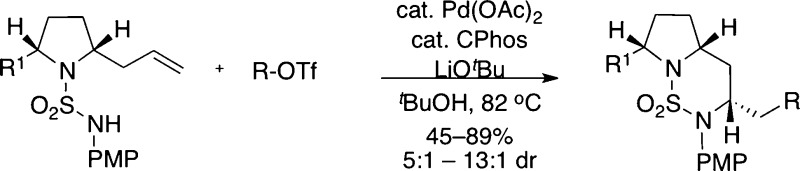

Over the past decade our group has developed a series of Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions between aryl or alkenyl halides and alkenes bearing pendant nitrogen nucleophiles.1 These reactions have proven useful for the stereoselective construction of a broad array of nitrogen heterocycles2−4 and have been demonstrated to proceed through a mechanism involving syn-aminopalladation of an intermediate palladium amido complex that leads to net syn-addition of the heteroatom and the aryl/alkenyl group to the double bond (Scheme 1).5 Although these transformations are synthetically useful, the relative stereochemistry of the heterocyclic products formed from substrates that contain stereogenic centers is invariably substrate-controlled. For example, we have demonstrated that Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions between aryl or alkenyl bromides and 2-allylpyrrolidinyl urea substrates such as 1 provide products 2 that contain a cis-relationship between the C-3 alkyl chain and the C-4a hydrogen atom when a mixture of Pd2(dba)3 and PCy3 is employed as the catalyst along with NaOtBu as a base (Scheme 1).6 This relative stereochemistry arises through syn-aminopalladation of the alkene via boat-like transition state 3.6

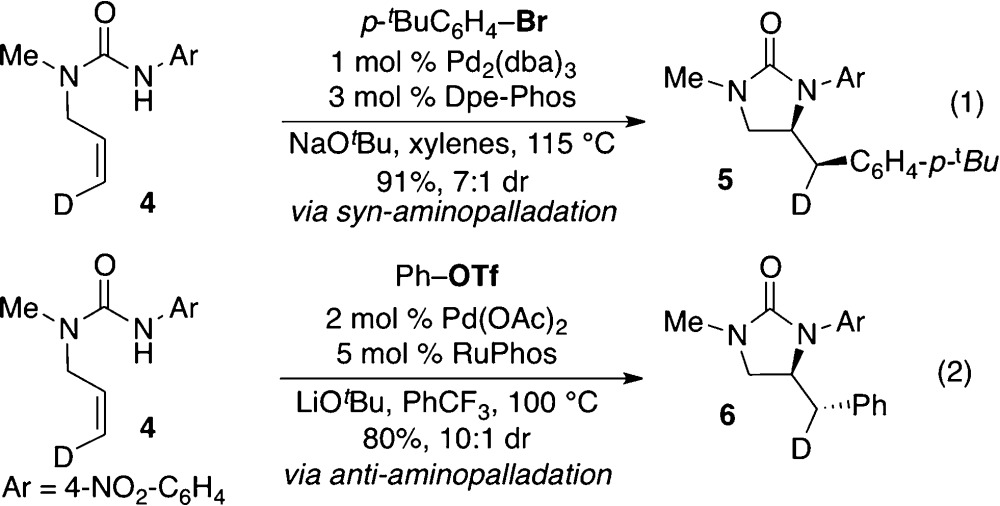

Scheme 1. Pd-Catalyzed Alkene Carboamination Reactions.

Recently, our group developed a method for the synthesis of cyclic sulfamides via Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions between N-allylsulfamides or N-allylureas and aryl triflates or bromides.7 During the course of these studies we demonstrated that either syn- or anti-addition products could be obtained under appropriate conditions.8 For example, coupling of 4 with an aryl bromide using a Pd/Dpe-Phos catalyst with NaOtBu as base and toluene as solvent afforded syn-addition product 5 (eq 1). In contrast, coupling of 4 with an aryl triflate using Pd/RuPhos and LiOtBu in PhCF3 solvent provided anti-addition product 6 (eq 2).

|

1 |

The influence of syn- vs anti-addition pathways on 1,2-asymmetric induction is quite obvious: 1,2-disubsituted alkenes such as 4 will be transformed to different stereoisomeric products depending on reaction mechanism, as the 1,2-addition to the alkene generates two stereocenters. However, we reasoned that syn- vs anti-addition pathways may also influence relative stereochemistry in systems involving monosubstituted alkene substrates that also contain stereocenters in relatively close proximity to the alkene. Herein we report the first examples of reactions in which syn- vs anti-aminopalladation pathways can be manipulated to control 1,3-asymmetric induction. These transformations generate synthetically useful bicyclic sulfamide products that are potentially valuable intermediates in the synthesis of polycyclic alkaloids.9−11

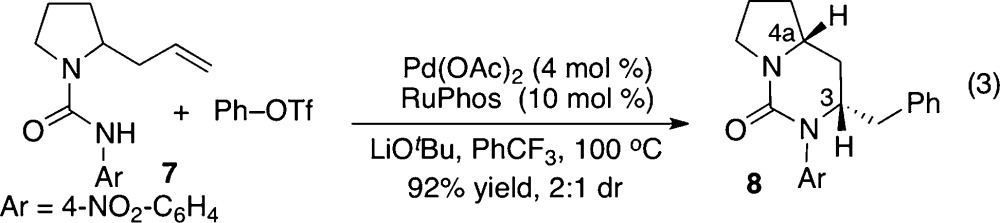

To probe the influence of aminopalladation mechanism on 1,3-asymmetric induction, we initially elected to examine the Pd-catalyzed carboamination between 2-allylpyrrolidinyl urea 7 and phenyl triflate (eq 3) using the optimized anti-aminopalladation conditions described for the synthesis of cyclic ureas and sulfamides.7 Gratifyingly, the desired product 8 was generated in excellent yield (92%), and the product stereochemistry was reversed (2:1 dr trans:cis) from that obtained using syn-aminopalladation conditions (Scheme 1). However, efforts to improve the selectivity of the transformation through the use of other protecting groups, ligands, solvents, and reaction temperatures were largely ineffective.12

|

3 |

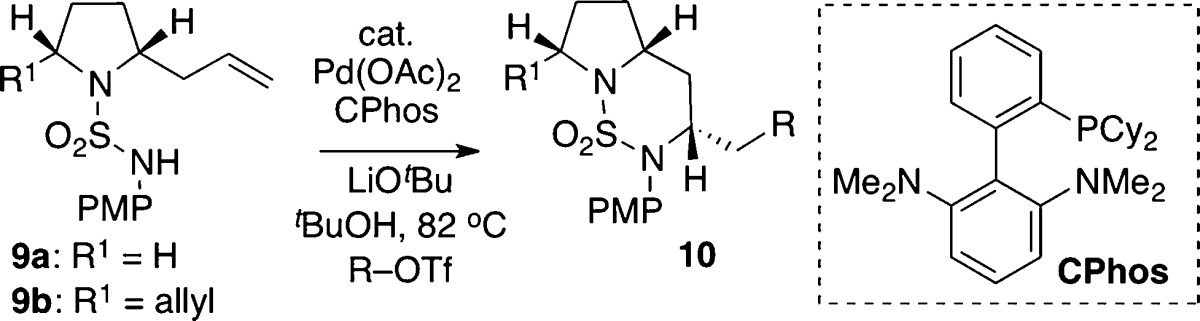

Although our preliminary studies with urea substrate 7 did not provide fully satisfactory results, the observed reversal in stereoselectivity was encouraging. We felt that selectivities might be higher in transformations of analogous sulfamide derivatives due to the differences in atomic geometry (pyramidal vs trigonal N-atom geometry, tetrahedral sulfur bearing two O atoms vs trigonal carbon bearing one) and nitrogen nucleophilicity. To probe this hypothesis, 2-allylpyrrolidinyl sulfamide substrate 9a was synthesized and treated with PhOTf using several different catalysts (Table 1).13,14 The coupling of 9a and phenyl triflate under the previously optimized conditions led to an improvement in selectivity, affording 10a in 6:1 dr favoring the trans-stereoisomer (entry 1).15 Unfortunately, several of the ligands screened led to low yields of desired product 9a and generated significant amounts of side products resulting from Heck arylation of the alkene (11) and/or β-hydride elimination from intermediate palladium complexes (12 and 13). CPhos provided the best results, but side products 11–13 were still formed in substantial quantities (entry 5). Moreover, the coupling of 9a with phenyl triflate proved to be highly variable, making it difficult to obtain consistently high and reproducible yields. After some experimentation, it was discovered that changing the solvent from benzotrifluoride to tert-butanol led to significantly improved and reproducible yields, and just as importantly, side products 11–13 were generated in only trace amounts (entry 6).16,17

Table 1. Ligand and Solvent Optimizationa.

| entry | solvent | ligand | NMR yieldb (isolated yield)c | dr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PhCF3 | RuPhos | 50 | 6:1 |

| 2 | PhCF3 | DavePhos | 30 | 6:1 |

| 3 | PhCF3 | BrettPhos | 40 | 6:1 |

| 4 | PhCF3 | tBuXphos | 30 | 6:1 |

| 5 | PhCF3 | CPhos | 80 | 6:1 |

| 6 | tBuOH | Cphos | 90 (89)d | 7:1 |

Reaction conditions: 1.0 equiv 9a, 2.0 equiv Ph-OTf, 2.0 equiv LiOtBu, 4 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 10 mol % ligand, solvent (0.1 M), 100 °C, 16 h.

NMR yields were determined using phenanthrene as an internal standard.

Isolated yield (average of two or more runs).

The reaction was conducted at 82 °C.

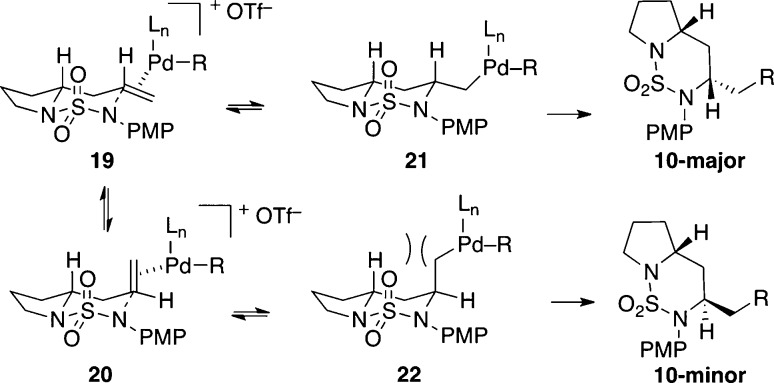

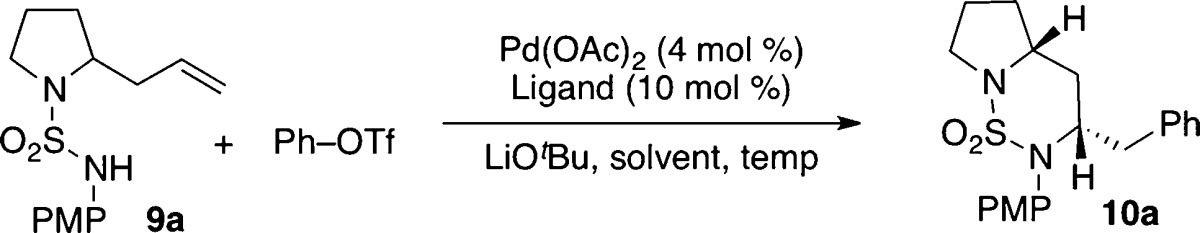

With optimized conditions in hand, the scope of the Pd-catalyzed carboamination methodology was examined by coupling N-PMP-protected pyrrolidinyl sulfamide substrates 9a and 9b with a variety of different aryl triflates (Table 2). Aryl triflates bearing either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups afforded bicyclic sulfamide products 10 in good yields and selectivities (entries 2–4 and 9). Additionally, the reaction of an ortho-substituted aryl triflate proceeded in good yield and with similar diastereoselectivity (entry 5). Alkenyl triflates also proved to be viable substrates, providing the desired bicyclic products with good selectivity but decreased yields (entries 6 and 7). Improved selectivities were observed for the cross-coupling reactions involving meso-2,5-diallyl-pyrrolidinyl sulfamide substrate 9b (entries 8 and 9), although shorter reaction times were required to minimize undesired isomerization of the remaining terminal olefin. In most cases the Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions did not lead to significant amounts of undesired side products; however, the competing formation of small amounts of 11–13 was occasionally observed.18

Table 2. Scope of Pd-Catalyzed Carboaminationa.

| entry | R1 | R | product | yield (%)b | drc (crude) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Ph | 10a | 89 | 7:1 |

| 2 | H | p-tBu-C6H4 | 10b | 78 | 6:1 |

| 3 | H | p-MeO-C6H4 | 10c | 70 | 7:1 |

| 4 | H | p-benzophenone | 10d | 61d | 8:1 (5:1) |

| 5 | H | o-Me-C6H4 | 10e | 87 | 5:1 |

| 6 | H | 1-cyclohexenyl | 10f | 63d | 6:1 |

| 7 | H | 1-decenyl | 10g | 45d | 10:1f,g |

| 8 | allyl | Ph | 10h | 65e | 20:1 (12:1) |

| 9 | allyl | p-MeO-C6H4 | 10i | 63e | >20:1 (13:1) |

Reaction conditions: 1.0 equiv 9a or 9b, 2.0 equiv R-OTf, 2.0 equiv LiOtBu, 4 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 10 mol % C-Phos, tBuOH (0.1 M), 82 °C, 16 h.

Isolated yield (average of two or more runs).

Diastereomeric ratio of the pure isolated material. Diastereomeric ratios of isolated materials were identical to those of the crude products unless otherwise noted.

The reaction was conducted with 3.0 equiv LiOtBu and 3.0 equiv R-OTf.

The reaction time was 2 h.

1-Decenyl triflate was employed as 5:1 mixture of E:Z isomers.

The dr was determined following hydrogenation of 10g. The crude dr of 10g could not be determined directly due to the mixture of diastereomers and E:Z isomer products. However, we estimate the crude dr to be ca. 5–10:1.

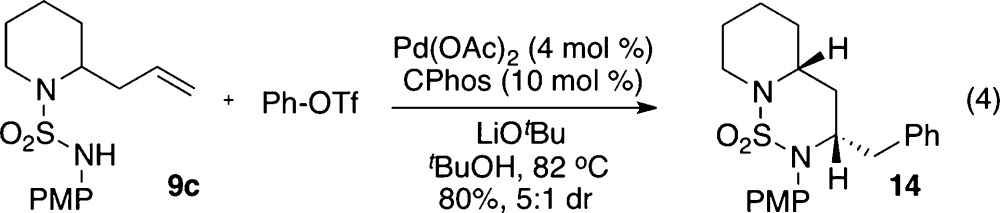

To further demonstrate the utility of this methodology, 2-allylpiperidinyl sulfamide substrate 9c was prepared and subjected to the optimized reaction conditions (eq 4). Gratifyingly, the coupling of 9c and phenyl triflate afforded the desired 6,6-fused bicyclic ring system in good chemical yield (80%) and with good stereocontrol (5:1 dr).

|

4 |

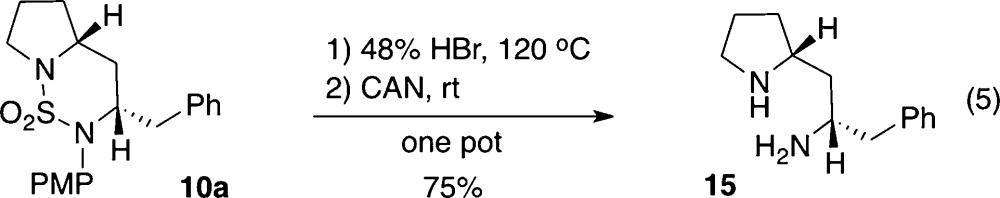

In order to illustrate the potential of these compounds as possible intermediates in the total synthesis of polycyclic alkaloid natural products, we sought to effect cleavage of the sulfamide bridge and removal of the N-PMP group. After some experimentation we found that treatment of 10a with HBr to effect desulfonylation19 followed by addition of CAN to oxidatively cleave the N-aryl group led to the formation of 15 in 75% yield (eq 5).

|

5 |

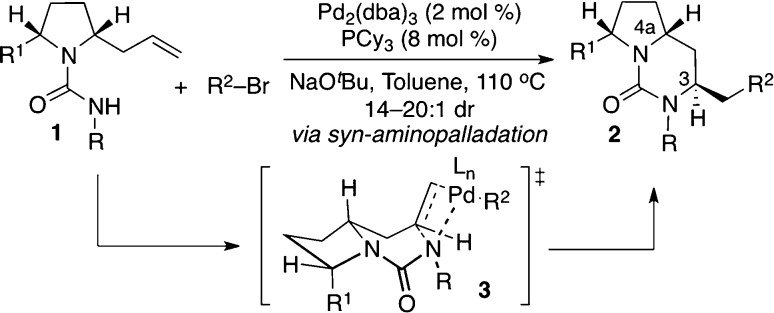

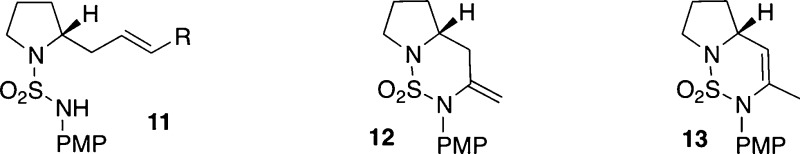

The mechanism of the Pd-catalyzed reactions for the formation of bicyclic sulfamides likely proceeds as depicted in Scheme 2.7 The catalytic cycle is initiated by oxidative addition of the aryl triflate to palladium(0) to generate cationic palladium complex 16.20 Activation of the olefin through coordination of the Pd-complex produces 17 and leads to outer-sphere nucleophilic attack of the sulfamide group onto the alkene (anti-aminopalladation). Reductive elimination from Pd-alkyl intermediate 18 affords the desired sulfamide product (10) and regenerates the palladium catalyst.

Scheme 2. Catalytic Cycle.

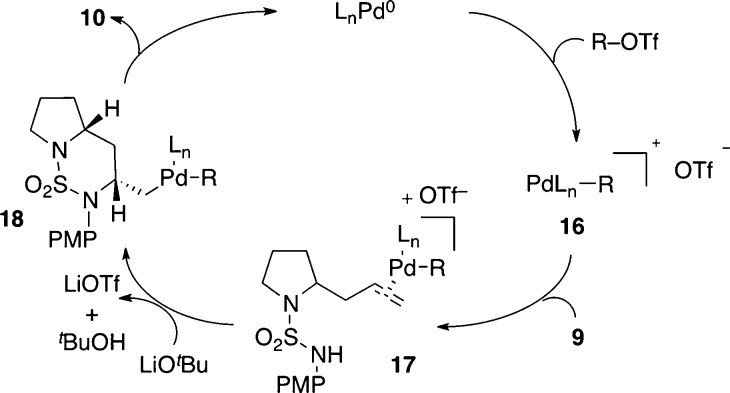

The stereochemical outcome of the Pd-catalyzed reactions for the synthesis of trans-bicyclic sulfamides is particularly interesting given the stereoselectivity of related carboamination reactions and the low selectivity generally observed for transformations involving anti-aminopalladation.21 Despite seemingly minor changes to the substrate, catalyst, and reaction conditions, the stereoselectivity of the carboamination reactions are dramatically altered, reversing a preference for the cis-stereoisomer (up to 20:1 dr) to form the trans-bicycle as the major product with good levels of stereocontrol (up to 13:1 crude dr). One possible explanation for the observed selectivity is that the stereochemical outcome is thermodynamically controlled and arises due to differences in the stability of chair-like intermediates 19 and 20, and/or 21 and 22 (Scheme 3).22,23 It appears that there are unfavorable 1,3-diaxial interactions in intermediates 20 and 22, where the olefin or alkylpalladium moiety occupies a pseudoaxial position. These steric interactions drive the equilibria toward 19 and 21. This model is consistent with the observed stereochemical outcome as aminopalladation from 19 and reductive elimination from 21 both lead to the major stereoisomer, whereas reductive elimination from 22 generates the minor diastereomer. The aminopalladation step is likely reversible in this system given the electron-deficient nature of the cyclizing nitrogen atom.5e,24 Since there are not obvious reasons why the relative rates of reductive elimination from 21 vs 22 should be significantly different, we favor a model where selectivity is thermodynamically controlled rather than dictated by kinetic factors.

Scheme 3. Stereochemical Model.

In conclusion, we have developed a new method for the synthesis of bicyclic sulfamides via the Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination of 2-allylpyrrolidinyl sulfamides. The reactions proceed in good yields and with good control of stereoselectivity (up to 13:1 dr). Importantly, this work illustrates that control of 1,3-asymmetric induction in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of closely related substrates can be achieved by varying catalyst structure, reaction conditions, and substrate structure (e.g., sulfamides vs ureas). These transformations provide access to synthetically useful bicyclic sulfamides and substituted pyrrolidin-2-yl-ethylamine derivatives. Studies on applications of this chemistry toward the total synthesis of polycyclic alkaloid natural products are currently underway.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the NIH-NIGMS (GM-071650) for financial support of this work.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures, characterization data, descriptions of stereochemical assignments, and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds reported in the text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Recent reviews:; a Wolfe J. P. Synlett 2008, 2913. [Google Scholar]; b Schultz D. M.; Wolfe J. P. Synthesis 2012, 44, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wolfe J. P. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2013, 32, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrrolidines:; a Ney J. E.; Wolfe J. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bertrand M. B.; Neukom J. D.; Wolfe J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Isoxazolidines:; c Lemen G. S.; Giampietro N. C.; Hay M. B.; Wolfe J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pyrazolidines:; d Giampietro N. C.; Wolfe J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Piperazines:; e Nakhla J. S.; Wolfe J. P. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morpholines:; f Leathen M. L.; Rosen B. R.; Wolfe J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Imidazolidin-2-ones:; g Fritz J. A.; Nakhla J. S.; Wolfe J. P. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Fritz J. A.; Wolfe J. P. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 6838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; I Hopkins B. A.; Wolfe J. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For Cu-catalyzed reactions, see:; a Chemler S. R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chemler S. R. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For Au-catalyzed reactions, see:; c Zhang G.; Cui L.; Wang Y.; Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Brenzovich W. E. Jr.; Benitez D.; Lackner A. D.; Shunatona H. P.; Tkatchouk E.; Goddard W. A. III; Toste F. D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Mankad N. P.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Tkatchouk E.; Mankad N. P.; Benitez D.; Goddard W. A. III; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For Pd-catalyzed arene C–H functionalization/alkene carboamination reactions of N-pentenyl amides that proceed via anti-aminopalladation through a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic cycle, see:; a Rosewall C. F.; Sibbald P. A.; Liskin D. V.; Michael F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sibbald P. A.; Rosewall C. F.; Swartz R. D.; Michael F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For studies on the mechanism of syn-migratory insertion of alkenes into Pd–N bonds, see:; a Neukom J. D.; Perch N. S.; Wolfe J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hanley P. S.; Marković D.; Hartwig J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Neukom J. D.; Perch N. S.; Wolfe J. P. Organometallics 2011, 30, 1269. [Google Scholar]; d Hanley P. S.; Hartwig J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e White P. B.; Stahl S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For reviews, see:; f Zeni G.; Larock R. C. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g McDonald R. I.; Liu G.; Stahl S. S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babij N. R.; Wolfe J. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornwald R. M.; Fritz J. A.; Wolfe J. P. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 10.1002/chem.201402258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We have previously shown that ligands can influence syn- vs. anti-heteropalladation pathways in intramolecular Pd-catalyzed carboalkoxylation and carboamination reactions. See:Nakhla J. S.; Kampf J. W.; Wolfe J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Takishima S.; Ishiyama A.; Iwatsuki M.; Otoguro K.; Yamada H.; Omura S.; Kobayashi H.; van Soest R. W. M.; Matsunaga S. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Takishima S.; Ishiyama A.; Iwatsuki M.; Otoguro K.; Yamada H.; Omura S.; Kobayashi H.; van Soest R. W. M.; Matsunaga S. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua H.-M.; Peng J.; Dunbar D. C.; Schinazi R. F.; de Castro Andrews A. G.; Cuevas C.; Garcia-Fernandez L. F.; Kelly M.; Hamann M. T. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 11179. [Google Scholar]

- For examples of polycyclic alkaloid synthesis that utilize related bicyclic intermediates, see:; a Snider B. B.; Chen J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5697. [Google Scholar]; b Overman L. E.; Rabinowitz M. H.; Renhowe P. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 2657. [Google Scholar]; c Aron Z. D.; Overman L. E. Chem. Commun. 2004, 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shimokawa J.; Ishiwata T.; Shirai K.; Koshino H.; Tanatani A.; Nakata T.; Hashimoto Y.; Nagasawa K. Chem.—Eur. J. 2005, 11, 6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Arnold M. A.; Day K. A.; Durón S. G.; Gin D. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Evans P. A.; Qin J.; Robinson J. E.; Bazin B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Rama Rao A. V.; Gurjar M. K.; Vasudevan J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995, 1369. [Google Scholar]; h Babij N. R.; Wolfe J. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Employing the ligand Trixiephos did lead to some improvement in diastereoselectivity (2.6:1 dr) without compromising the chemical yield of the reaction (91% NMR yield).

- The sulfamide substrates 9a, 9b, and 9c were prepared in 3 or 4 steps from commercially available materials.

- Structures of the ligands named in Table 1 are provided in the Supporting Information.

- Other protecting groups provided inferior results; see the Supporting Information for further details.

- The use of tBuOH in the carboamination of 7 with phenyl triflate led to the formation of 8 in diminished yield and selectivity (1.2:1 dr).

- For selected examples of other Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions where tBuOH solvent leads to improved rates, yields, or selectivities, see:; a Huang X.; Anderson K. W.; Zim D.; Jiang L.; Klapars A.; Buchwald S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bagdanoff J. T.; Ferreira E. M.; Stoltz B. M. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shekhar S.; Dunn T. B.; Kotecki B. J.; Montavon D. K.; Cullen S. C. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lucciola D.; Keay B. A. Synlett 2011, 1618. [Google Scholar]; e Garcia-Fortanet J.; Buchwald S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- When benzotrifluoride was employed as the solvent, substantial quantities of 11–13 were generated in a number of reactions. For example, when the coupling of 9b and phenyl triflate was conducted in benzotrifluoride, the yield of the desired product (10h) was modest (57%) and was not separable from β-hydride elimination side products 12 and 13 (∼25%) via flash chromatography.

- The O-methyl group present on the N-PMP substituent was also cleaved under these conditions. However, oxidative cleavage of the N-p-hydroxyphenyl group proceeded smoothly.

- Jutand A.; Mosleh A. Organometallics 1995, 14, 1810. [Google Scholar]

- The selectivities for Pd- or Au-catalyzed carboamination reactions proceeding via an anti-aminometalation mechanism are generally low for substrates bearing nonallylic substituents. See refs (3c), (3d), and (4a).

- For other six-membered ring-forming reactions involving anti-aminopalladation pathways that are proposed to involve chair-like transition states, see:; a Hirai Y.; Watanabe J.; Nozaki T.; Yokoyama H.; Yamaguchi S. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 776. [Google Scholar]; b Yokoyama H.; Otaya K.; Kobayashi H.; Miyazawa M.; Yamaguchi S.; Hirai Y. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The possibility that these transformations are actually under kinetic control and/or that the selectivity arises from boat-like transition states/intermediates similar to those described in ref (6) cannot be ruled out. However, this type of model does not seem consistent with the selective formation of trans-bicyclic sulfamides, as the boat-like transition state leading to the observed major isomer appears to suffer from unfavorable steric interactions and overall appears to be much higher in energy than the analogous chair-like intermediates 19 and 20.

- Timokhin V. I.; Stahl S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.