Abstract

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, structural diversities of complex sphingolipids [inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC), mannosylinositol phosphorylceramide, and mannosyldiinositol phosphorylceramide] are often observed in the presence or absence of hydroxyl groups on the C-4 position of long-chain base (C4-OH) and the C-2 position of very long-chain fatty acids (C2-OH), but the biological significance of these groups remains unclear. Here, we evaluated cellular membrane fluidity in hydroxyl group-defective yeast mutants by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. The lateral diffusion of enhanced green fluorescent protein-tagged hexose transporter 1 (Hxt1-EGFP) was influenced by the absence of C4-OH and/or C2-OH. Notably, the fluorescence recovery of Hxt1-EGFP was dramatically decreased in the sur2Δ mutant (absence of C4-OH) under the csg1Δcsh1Δ background, in which mannosylation of IPC is blocked leading to IPC accumulation, while the recovery in the scs7Δ mutant (absence of C2-OH) under the same background was modestly decreased. In addition, the amount of low affinity tryptophan transporter 1 (Tat1)-EGFP was markedly decreased in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant and accumulated in intracellular membranes in the scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant without altering its protein expression. These results suggest that C4-OH and C2-OH are most probably critical factors for maintaining membrane fluidity and proper turnover of membrane molecules in yeast containing complex sphingolipids with only one hydrophilic head group.

Keywords: sphingolipids, glycolipids, membranes/fluidity, lipid rafts, yeast, hydroxyl group, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The plasma membrane, which typically contains glycerophospholipids (∼40–60%), sphingolipids (∼10–20%), and sterols (∼30–40%) (1), is now recognized as a complex organelle organized into lateral domains. In mammals, these domains, known as lipid microdomains (or rafts), comprise sphingolipids and cholesterol and function as platforms for effective signal transduction (2–4). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, three similar domains are assumed: the membrane compartment containing Pma1 (MCP), the eisosome/membrane compartment containing Can1 (MCC), and the membrane compartment containing target of rapamycin kinase complex 2 (MCT) (5–7). Microscopically, these domains appear as either mutually exclusive punctate (MCC and MCT) or as a network winding between the other domains (MCP). To date, there is no evidence whether these domains function similarly to lipid microdomains in mammals. Pma1 is the most abundant yeast plasma membrane protein, and it associates with sphingolipids during its transport to the plasma membrane (8–11). The MCC is enriched in transporters such as Can1, and is coated by eisosomes, which are large peripheral membrane protein complexes (12). The MCT is distinct from and nonoverlapping with the MCC, although the mechanism of its formation remains unclear (7).

Whereas MCC is likely a sterol-rich domain, MCP mainly contains three complex sphingolipids, inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC), mannosylinositol phosphorylceramide (MIPC), and mannosyldiinositol phosphorylceramide [M(IP)2C] (8–10, 13). However, the difference in sphingolipid compositions among MCC, MCP, and MCT are still not clearly understood. These complex sphingolipids correspond to mammalian glycosphingolipids. Glycosphingolipids have hundreds of molecular species differing in number and/or type of sugar chain (14), yet the composition of complex sphingolipids in yeast is quite simple. IPC comprises a common ceramide backbone carrying a phosphoinositol and is synthesized by Aur1 (Fig. 1) (15). MIPC is formed by the addition of mannose to IPC, which is catalyzed by either of two homologous IPC mannosyltransferases, Csg1 or Csh1 (16), and M(IP)2C is formed by the addition of phosphoinositol to MIPC (17). IPC synthesis, but not MIPC and M(IP)2C synthesis, is essential for cell growth (15). Nevertheless, MIPC synthesis is important for Ca2+ signaling, and M(IP)2C is involved in oxidative stress (16, 18, 19).

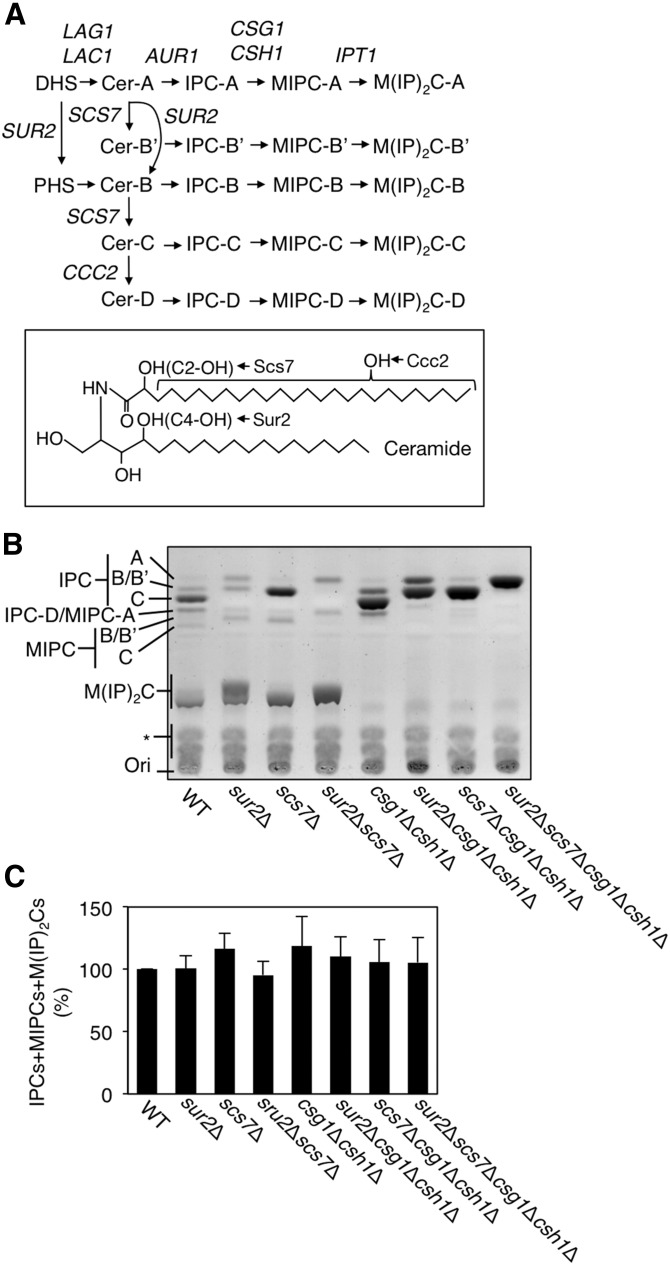

Fig. 1.

A: Comparisons of sphingolipid composition in a series of yeast mutants. Shown are the pathways for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis and the genes involved at each step. Because of the different hydroxylation states of ceramide (Cer-A, B′, B, C, and D), there are five species each for IPC, MIPC, and M(IP)2C. B: Total lipids were extracted from 3.5 OD600 units of KA31-1A (WT), SUY12 (sur2Δ), SUY16 (scs7Δ), SUY359 (sur2 Δscs7Δ), SUY65 (csg1Δcsh1Δ), SUY401 (sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ), SUY54 (scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ), and SUY434 (sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ) cells and treated with mild alkaline solution to hydrolyze glycerophospholipids. The lipids were separated on a TLC plate and complex sphingolipids were visualized using 10% copper sulfate-8% orthophosphoric acid reagent. C: The expression levels of total complex sphingolipids (IPCs + MIPCs + M(IP)2Cs) were quantified with ImageJ software. The quantitative data are expressed as mean values with SDs from more than three independent experiments.

Yeast complex sphingolipids are classified into five species (A, B′, B, C, and D), which differ in the position and/or number of hydroxyl groups within the ceramide moiety (Fig. 1) (20). The hydroxylation on the C-4 position of the long-chain base (LCB) and the C-2 position of the very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) is catalyzed by Sur2 and Scs7, respectively (20). D species are generated by further hydroxylation at an unknown position of the fatty acid moiety of ceramide-C (18). Mammalian homologs of Sur2 and Scs7 have been identified as DES2 (expressed in skin, intestine, and kidney) and FA2H (expressed in brain and skin), respectively (21–27). The specific functions of hydroxylated complex sphingolipids and glycosphingolipids are not fully understood. However, it appears that the hydroxyl group on the C-2 position of VLCFAs (C2-OH) is necessary for the normal function of the mammalian nervous system, as mutations in the FA2H gene have been discovered in patients with hereditary leukodystrophy with spastic paraparesis (28, 29).

In the present study, we sought to clarify the biological significance of the hydroxyl groups in complex sphingolipids. We examined the mobility of the membrane protein’s low affinity tryptophan transporter 1 (Tat1) and low affinity hexose transporter 1 (Hxt1) in a series of mutants defective in the hydroxyl group on the C-4 position (C4-OH) of LCB and/or C2-OH in WT and csg1Δcsh1Δ backgrounds using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis. The term “membrane fluidity” denotes two distinct physicochemical properties of the membrane that are indicative of: i) the lateral diffusion of lipids and protein molecules within the bilayer membrane, and ii) local viscosity of the membrane characterized by rotational motion of lipid acyl chains. FRAP analysis measures the lateral diffusion of labeled proteins/lipids, while fluorescence anisotropy measurement determines the local viscosity of membrane lipids by examining the rotational Brownian motion of acyl chains. Here, we use membrane fluidity to describe the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins/lipids. In the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants, the lateral diffusion of Hxt1-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was remarkably reduced, but its oligomer formation in the plasma membrane was hardly affected. In addition, the protein expression of Tat1-EGFP was decreased in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants, while the subcellular localization in the scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was abnormal without altered protein expression. We speculate that the reduced lateral diffusion of Hxt1-EGFP and the aberrant turnover of Tat1-EGFP were caused by an enhanced interaction between complex sphingolipids that resulted from C4-OH and/or C2-OH defects present in the csg1Δcsh1Δ background; such defects result in only one hydrophilic head group.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast strains and media

The S. cerevisiae strains used are listed in Table 1. The construction of csg1Δ::HIS3 and csh1Δ::LEU2 was described previously (16). The sur2Δ::URA3 and scs7Δ::URA3 cells were constructed by replacing each of their entire open reading frames with the URA3 marker. Cells were grown either in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose) or in synthetic complete (SC) medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base and 2% glucose) containing nutritional supplements.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

| KA31-1A | MATa ura3 leu2 his3 trp1 | (63) |

| SUY12 | KA31-1A, sur2Δ::KanMX4 | (16) |

| SUY16 | KA31-1A, scs7Δ::KanMX4 | (16) |

| SUY359 | KA31-1A, sur2Δ::URA3 scs7Δ::KanMX4 | This study |

| SUY65 | KA31-1A, csg1Δ::HIS3 csh1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| SUY401 | KA31-1A, sur2Δ::KanMX4 csg1Δ::HIS3 csh1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| SUY54 | KA31-1A, scs7Δ::KanMX4 csg1Δ::HIS3 csh1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| SUY434 | KA31-1A, sur2Δ::KanMX4 scs7Δ::URA3 csg1Δ::HIS3 csh1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

Plasmids

The pSU234 (TRP1 marker, 2 μ) plasmid is a yeast vector constructed to produce fusion proteins containing a C-terminal EGFP. For construction of pFS326 (HXT1-EGFP, TRP1, 2 μ), the HXT1 region containing its own promoter was amplified using genomic DNA prepared from KA31-1A cells and the primers 5′-TTGATATCGAATTCCTGCAGGAGACAGCGCAAAGGATTATGACAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTCACCATGGATCCTTTCCTGCTAAACAAACTCTTGTAAAATGGTTGG-3′. The resulting fragments were cloned into the PstI-BamHI site of pSU234 using an In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) to generate the pFS326 plasmid. The pSU235 (TAT1-EGFP, TRP1, 2 μ) and pSU259 (PMA1-EGFP, TRP1, 2 μ) plasmids were constructed by similar procedures.

Lipid analysis

Cells were cultured overnight in YPD medium, diluted [0.4 optical density measured at 600 nm (OD600) units/ml] in 8 ml of fresh YPD medium, and incubated for 4 h. The cells (3.5 OD600 units) were chilled on ice, collected by centrifugation, washed two times with distilled water, and then suspended in 350 μl of ethanol/water/diethyl ether/pyridine/15 N ammonia (15:15:5:1:0.018, v/v). After 15 min incubation at 65°C, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 1 min and the supernatants were withdrawn. Lipids were extracted from the residues once more in the same manner. The resulting supernatants were dried. For mild alkaline treatment, the lipid extracts were dissolved in 130 μl monomethylamine (40% methanol solution)/water (10:3, v/v), incubated for 1 h at 53°C, and then dried. The lipids were suspended in 30 μl of chloroform/methanol/water (5:4:1, v/v) and then separated on Silica Gel 60 TLC plates (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ) with chloroform/methanol/4.2 N ammonia (9:7:2, v/v) as the solvent system. The TLC plates were sprayed with 10% copper sulfate in 8% orthophosphoric acid and then heated at 180°C to visualize complex sphingolipids.

To determine the amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids present in the plasma membrane, we prepared P13 fractions from WT and mutant cells. The cells (40 OD600 units) were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with 10 mM NaN3-10 mM NaF, and washed once in lysis buffer A [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaN3]. The cells were suspended with lysis buffer A containing 1× Complete™ protease inhibitor mixture, then mixed vigorously with glass beads. After removal of cell debris by a 5 min centrifugation at 900 g at 4°C, the supernatant was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The final precipitates (P13 fraction) were suspended in ultrapure water, mixed with Triton X-100 (final concentration, 9%) and isopropyl alcohol (final concentration, 45%), and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids were determined by a Wako cholesterol E test (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and Wako phospholipid C test (Wako), respectively. Protein concentrations were determined with a Pierce® BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) using P13 fraction.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells grown to exponential phase were prepared and diluted with YPD or SC medium to an OD600 value of 0.1. The diluted cells were poured into sterilized tubes and incubated for 20 h at 30°C. After 4, 8, 12, 16, or 20 h, cell proliferation was evaluated by measuring each OD600 value.

FRAP analysis

For microscopy, cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C until early log phase. Cells were adhered to a concanavalin-A-coated glass base dish (35 mm diameter) (Asahi Glass Co., Tokyo, Japan) and imaged in SC medium. Imaging was performed at 30°C on a heat-controlled stage of an Olympus FV1000 microscope with a UPlanSApo 60× oil-immersion objective (NA 1.35; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Bleaching of outlined regions of interest (circle, radius of 4 pixels) was performed at 30°C with an open pinhole, with a 488 nm laser at full power. The fluorescence curves of individual experiments (n = 41–125) were averaged and the averaged curve was fitted to calculate the recovery half times (t1/2 = ln2/k) with the formulas: y = y0 + A[1 − exp(−kt)] (one component model) or y = y0 + A1[1 − exp(−k1t)] + A2[1 − exp(−k2t)] (two component model), where y0 is the first postbleach intensity, A is the component ratio, and k is a rate constant.

The fluorescence recovery of Pma1-EGFP, Tat1-EGFP, or Hxt1-EGFP in each yeast strain was measured 15–20 times per day (n = 15–20). From the data on day 1, a fluorescence recovery curve was obtained, and the t1/2 and mobile fraction (Mf) were calculated by fitting the curve to a theoretical curve. This experiment was independently performed more than three times for each strain, and the mean values with SD of t1/2 and Mf were calculated. The fluorescence recovery curves in Figs. 3, 6, and 7 illustrate the average and standard deviation of all recovery data (n = 41–125) in one strain.

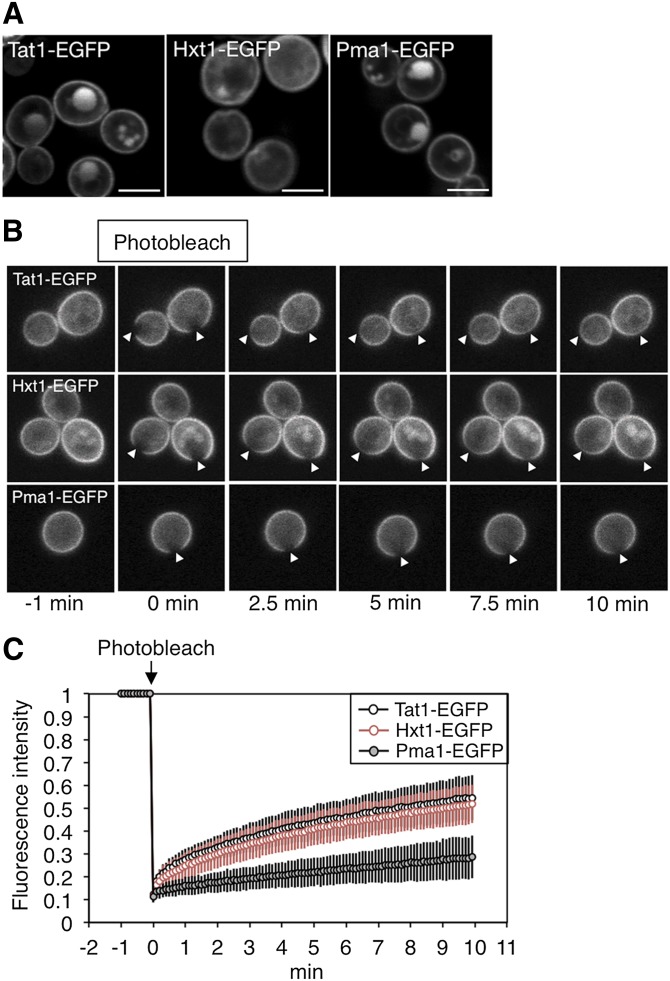

Fig. 3.

FRAP analyses of Tat1-EGFP, Hxt1-EGFP, and Pma1-EGFP in WT yeast cells. A: The subcellular localizations of Tat1-EGFP, Hxt1-EGFP, and Pma1-EGFP in KA31-1A (WT) cells cultured in YPD medium were observed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope. The white lines indicate 5 μm. B, C: Fluorescent areas in WT cells expressing Tat1-EGFP (n = 64), Hxt1-EGFP (n = 59), or Pma1-EGFP (n = 83) were bleached at 0 min. Fluorescence recovery was measured over 10 min. Selected frames were examined at −1, 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 min. The white arrowheads indicate the bleached regions (B). Each fluorescence recovery curve is represented by the mean fluorescence intensity with SD from the indicated number of experiments (C).

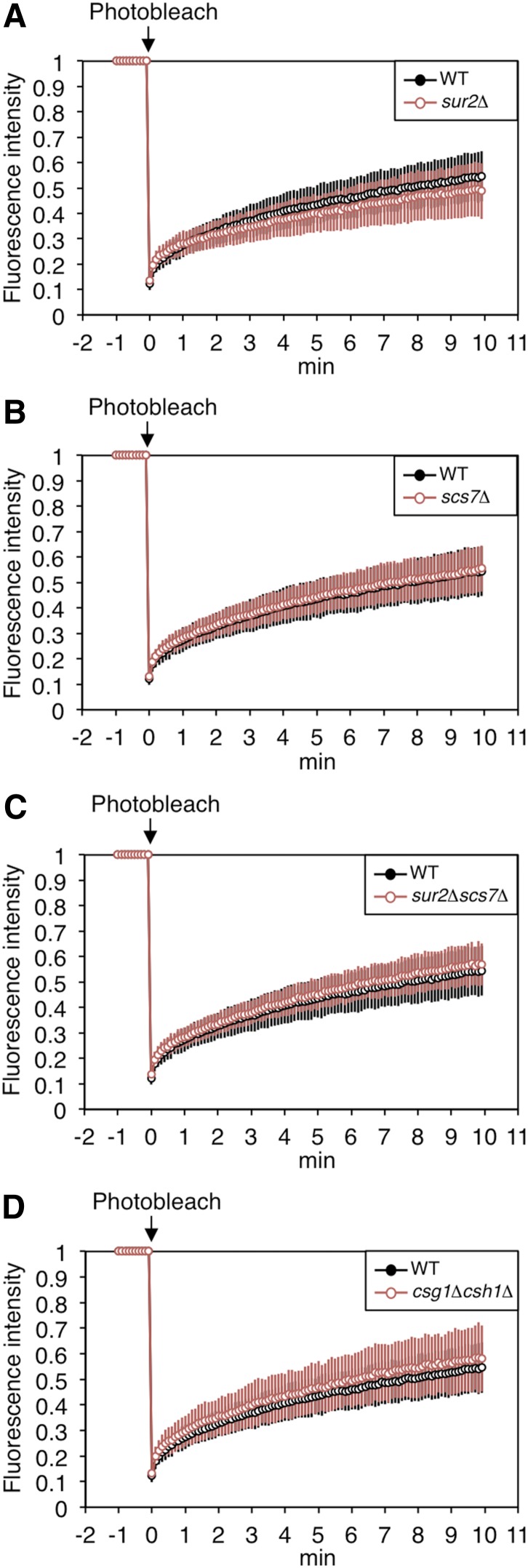

Fig. 6.

Lateral diffusion of Tat1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants. The fluorescent areas in WT or mutant cells expressing Tat1-EGFP [sur2Δ, n = 77 (A); scs7Δ, n = 74 (B); sur2Δscs7Δ, n = 76 (C); and csg1Δcsh1Δ, n = 49(D)] were bleached at 0 min. The fluorescence recovery was measured over 10 min. Each fluorescence recovery curve is represented by the mean fluorescence intensity with SD from the indicated number of experiments.

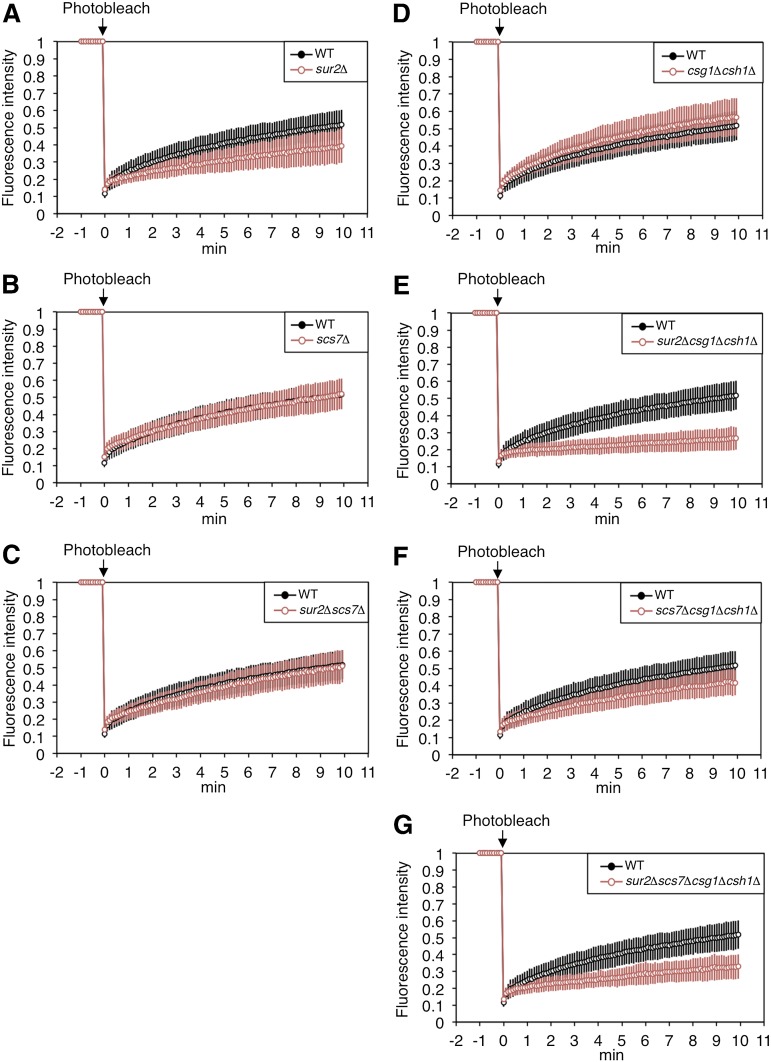

Fig. 7.

Lateral diffusion of Hxt1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants. The fluorescent areas in WT or mutant cells expressing Hxt1-EGFP [sur2Δ, n = 41 (A); scs7Δ, n = 68 (B); sur2Δscs7Δ, n = 47 (C); csg1Δcsh1Δ, n = 125 (D); sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, n = 110 (Ε); scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, n = 77 (F); and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, n = 78 (G)] were bleached at 0 min. The fluorescence recovery was measured over 10 min. Each fluorescence recovery curve is represented by the mean fluorescence intensity with SD from the indicated number of experiments.

Preparation of cell lysates

Cells (1.65 × 108) were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with 10 mM NaN3-10 mM NaF, and washed once in lysis buffer A [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaN3]. The cells were suspended with lysis buffer A containing 1× Complete™ protease inhibitor mixture and mixed vigorously with glass beads. After removal of cell debris by a 5 min centrifugation at 900 g at 4°C, the supernatant (total cell lysates) was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The precipitates (P13 fraction) were suspended in 2× sample buffer [125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and a trace amount of bromophenol blue] containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, then incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Protein concentrations were determined with a Pierce® BCA protein assay kit using total cell lysates.

Blue native PAGE

P13 fractions were solubilized with 2% SDS at room temperature or with 1% digitonin (DG) at 4°C, mixed for 15 min in 1× NativePAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), then centrifuged for 30 min at 20,000 g at room temperature (SDS) or 4°C (DG). NativePAGE 5% G-250 sample additive (Invitrogen) was added to the supernatant, and the proteins were separated on a 3–12% polyacrylamide gradient gel (Invitrogen) with NativePAGE™ unstained protein standard (Invitrogen).

Immunoblotting

Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE or blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and transferred to an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Anti-GFP antibodies (IgY fraction) (1:4,000 dilution, Aves Labs, Inc., Tigard, OR) were used as primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-chicken IgY (1:10,000, Aves Labs, Inc.) was used as the secondary antibody. Labeling was detected using an ECL™ select kit (GE Healthcare Bioscience, Little Chalfont, UK).

RESULTS

Decreased cell growth resulting from defects in C4-OH of LCB in a csg1Δcsh1Δ background

In S. cerevisiae, complex sphingolipids in the plasma membrane exist in five hydroxylation states (A, B′, B, C, and D species). To clarify the physiological significance of the hydroxylation on the C-4 of LCB by Sur2, and on the C-2 of the VLCFA of ceramides by Scs7, we constructed a series of mutants: sur2Δ, scs7Δ, sur2Δscs7Δ, csg1Δcsh1Δ, sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ. To confirm the composition of complex sphingolipids in WT and the mutant cells, the total lipids were extracted, treated with mild alkaline solution, and separated by TLC (Fig. 1B, C). In WT cells, IPC, MIPC, and M(IP)2C were detected, each with several hydroxylation states. In the sur2Δ and scs7Δ mutants, A and B′ species and A and B species of complex sphingolipids were detected, respectively. As expected, the sur2Δscs7Δ mutant exhibited only A species. In the csg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, which is defective in the conversion of IPC to MIPC, both MIPC and M(IP)2C were completely absent. Thus, the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ, and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants exhibited only IPC-A and IPC-B′, IPC-A and IPC-B, and IPC-A, respectively, as complex sphingolipids. Moreover, the amounts of total complex sphingolipids [IPC + MIPC + M(IP)2C] in all mutant cells were similar to those in WT cells (Fig. 1C).

To investigate whether the changes of sphingolipid biosynthesis affect the compositions of other plasma membrane lipids, we quantified the amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids in P13 fractions isolated from plasma membranes. The P13 fractions were prepared from 40 OD600 units of WT and mutant cells, and the amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids were determined by commercial tests for free cholesterol E and phospholipid C, respectively (Table 2). The amounts of phospholipids in all mutants were similar to those in WT cells. In contrast, the amount of ergosterol in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant alone was slightly decreased compared with that from WT cells. Thus, defects in the hydroxyl groups and/or glycan moieties of complex sphingolipids do not greatly affect the amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids in the plasma membrane except in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the amounts of ergosterol and phospholipids containing P13 fraction

| Ergosterol (ng/μg protein) | Phospholipids (ng/μg protein) | |

| WT | 8.38 ± 1.36 | 11.6 ± 1.6 |

| sur2Δ | 7.80 ± 1.08 | 10.8 ± 1.2 |

| scs7Δ | 7.83 ± 1.23 | 10.8 ± 1.4 |

| sur2Δscs7Δ | 7.32 ± 0.33 | 9.45 ± 0.58 |

| csg1Δcsh1Δ | 7.73 ± 1.50 | 10.9 ± 1.7 |

| sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 5.59 ± 0.40a | 9.39 ± 0.27 |

| scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 7.79 ± 2.12 | 10.9 ± 2.9 |

| sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 6.91 ± 1.13 | 10.6 ± 1.3 |

P < 0.05 as compared with WT.

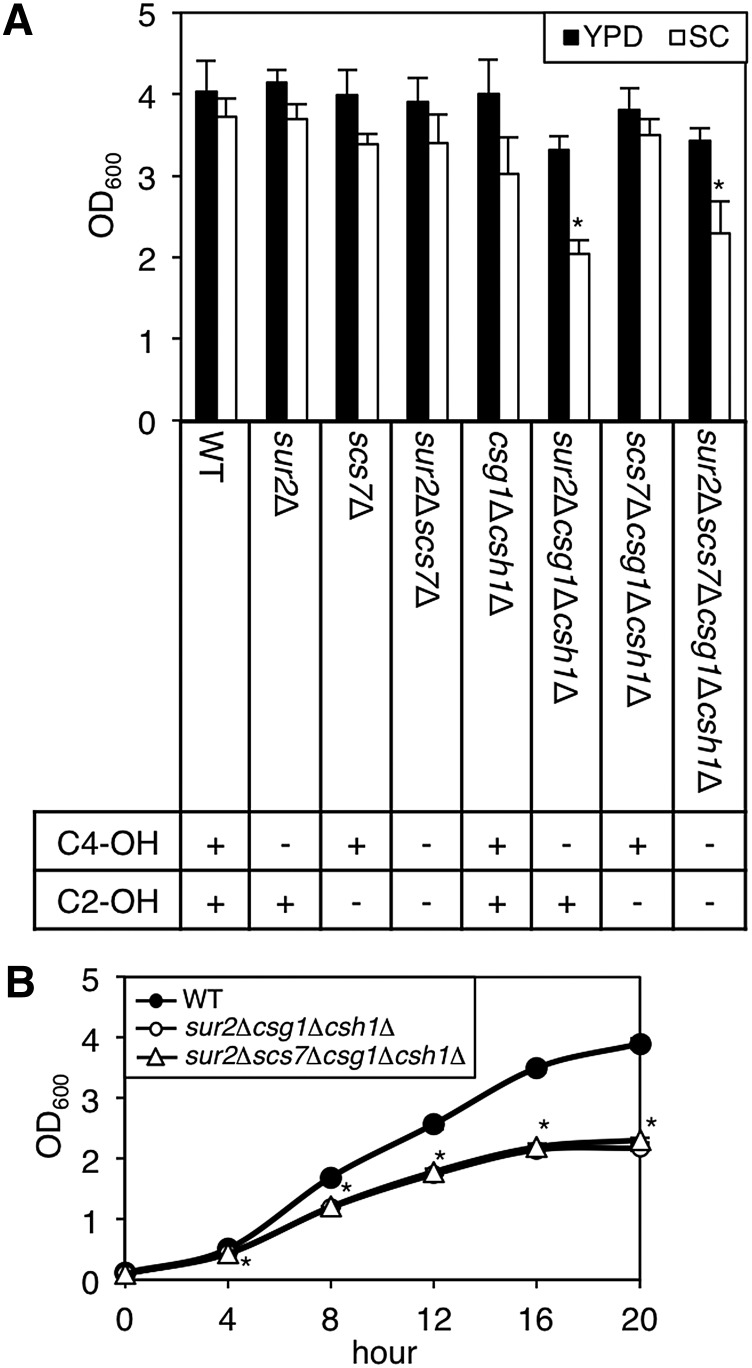

Next, we examined whether these changes in sphingolipid composition affected cell growth. The cells (1.65 × 106 cells/ml, OD600 = 0.1) were cultured in YPD or SC medium at 30°C for 20 h, and apparent OD600 (Fig. 2A). YPD medium is a nutritionally enriched medium and SC medium is a chemically defined medium containing essential nutrients required for yeast growth. Cell growth of the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants in SC medium was significantly decreased. In the same manner, we monitored the cell growth of WT, sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ cells in SC medium every 4 h (Fig. 2B). At all points, the cell growth of these mutants was lower than that of WT cells. These results suggest that the defect in SUR2 gene in the csg1Δcsh1Δ background causes decreased cell growth under limited nutrient conditions.

Fig. 2.

Cell growth in a series of yeast mutants. A, B: WT and mutant cells [1.65 × 106 cells/ml (OD600 = 0.1)] were cultured in YPD or SD medium at 30°C for 20 h (A) or in SD medium at 30°C for 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 h (B), and the apparent OD600 using a spectrophotometer. Data are expressed as mean values with SDs from more than three independent experiments. *P < 0.001 versus WT cells.

Membrane dynamics of yeast plasma membrane proteins as determined by FRAP analysis

Because sphingolipids form platforms for various proteins to function in the plasma membrane in mammals, we considered that the loss of the hydroxyl groups of the ceramide moiety might affect many cellular events and lead to the decrease of cell growth in certain culture conditions. Thus, to elucidate the fundamental roles of the hydroxyl groups, we focused on the physiological changes of the plasma membrane in the absence of C2-OH and/or C4-OH. The membrane dynamics of living cells or liposomes reconstituted from lipid extracts have been analyzed by others using C-laurdan spectroscopy or fluorescence membrane probes such as 1-[4-(trimetylamino)phenyl]6-phenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (TMA-DPH) and trans-parinaric acid (t-PnA) (30–33). However, no reports have addressed whether changes in sphingolipid composition affect the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins in yeast. Accordingly, we attempted to investigate the lateral diffusion of plasma membrane proteins in a series of mutants by FRAP analysis, which is a technique that examines protein mobility in living cells by measuring the percentage of fluorescence recovery at a bleached region. By fitting the fluorescence recovery curve to a theoretical curve designed for one or two membrane components, we can calculate the number of components diffusing through the membrane, the percentage of the Mf and immobile fraction (100-Mf), and the speed of lateral diffusion (t1/2). The percentages of mobile and immobile fractions indicate the amount of EGFP-fused membrane proteins existing in mobile and immobile regions, respectively. Therefore, we can estimate the plasma membrane fluidity by examining the mobility of membrane proteins.

Tat1, Hxt1, and Pma1 (plasma membrane H+-ATPase) were selected for use in FRAP analysis. These proteins (fused with EGFP) were mainly localized at the plasma membrane when cultured on YPD medium, which can maintain cell growth in all mutants (Fig. 3A). Reportedly, Hxt1 localizes in both the MCP and MCC (5), whereas the distribution of Tat1 has not been characterized. We bleached a region in the fluorescent area of these proteins and measured the fluorescence recovery over 10 min in each strain 15–20 times per day (Fig. 3B). A fluorescence recovery curve was obtained from the mean value of the data in 1 day. By fitting the curve to a theoretical curve, the t1/2 and Mf were calculated (Table 3). These experiments were independently performed at least three times for each strain. Each fluorescence recovery curve in Fig. 3C illustrates the mean value and standard deviation of all data (n = 59–83). The fluorescence of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP had partly recovered at 10 min, while the fluorescence recovery of Pma1-EGFP was very low. The results of an exponential approximation using these fluorescence recovery curves indicated that Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP present as two diffusing components, whereas Pma1-EGFP presents as only one diffusing component (Table 3). The slow-t1/2 and fast-t1/2 of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP were 4.7–5.1 min and 0.13–0.17 min, respectively. The variation observed in fluorescence recovery may be partly attributed to slight differences in cell conditions. However, we assume that the variation falls within the range of experimental error resulting from the technical limitations of FRAP analysis when used on small yeast cells. Moreover, newly synthesized and delivered proteins may also be partly involved in the fluorescence recovery. However, in the time scale of FRAP analysis, such effects should be minimized because the turnover of Tat1-EGFP, Hxt1-EGFP, and Pma1-EGFP was relatively slow (data not shown). About one-half of the Tat1-EGFP or Hxt1-EGFP existed in mobile regions, and the percentages of the slow-Mf for Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP were about 5-fold higher than the percentage of fast-Mf for these proteins. These results mean that most of the mobile molecules move slowly in the plasma membrane. On the other hand, Pma1-EGFP presents as only one component, and its percentage of Mf was 35.5 ± 7.7, which was lower than the total Mf (slow-Mf + fast-Mf) for Tat1-EGFP or Hxt1-EGFP. Moreover, the t1/2 for Pma1 was much higher than the slow-t1/2 for Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP, indicating that the speed of the lateral diffusion of Pma1 was remarkably slower than that of the other proteins. Presumably, the rotational acyl chain motion of the MCP and MCC would be low, because sphingolipids containing saturated fatty acid and ergosterol accumulate in these domains, and so the MCP and MCC could be packed. Thus, the slow-t1/2 for Tat1-EGFP or Hxt1-EGFP might reflect the speed of molecules existing in the MCP and/or MCC, while a fast-t1/2 would indicate the mobility of molecules existing in other domains such as a glycerolipid-enriched compartment. The percentages of immobile fractions likely also reflect the properties of membrane proteins localized in the MCP and/or MCC. Because the fluorescence recovery of Hxt1-EGFP included the lateral diffusion not only in the MCC but also in the MCP, the dramatic decrease in the lateral diffusion of Pma1 cannot be explained by selective MCP localization alone.

TABLE 3.

Exponential approximation of EGFP-tagged plasma membrane proteins in WT yeast cells

| t1/2 (min) | Mf (%) | |||

| Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | |

| Tat1-EGFP | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 42.7 ± 4.8 | 9.3 ± 1.4 |

| Hxt1-EGFP | 4.74 ± 0.69 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 42.2 ± 5.8 | 7.1 ± 1.7 |

| Pma1-EGFP | 11.1 ± 4.1 | 35.5 ± 7.7 | ||

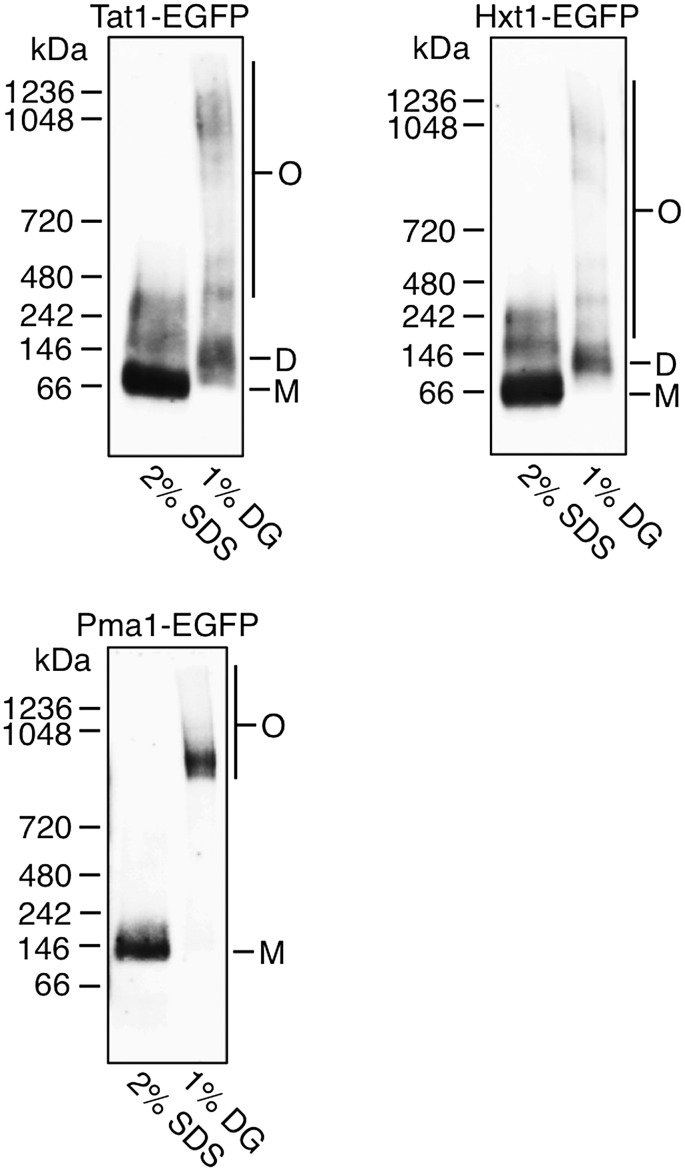

Pmal reportedly forms a large oligomeric complex in the endoplasmic reticulum and is transported to the plasma membrane (9). To investigate the relationship between such oligomeric formation and the decrease in lateral diffusion, we examined whether Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP each form oligomeric complexes in the plasma membrane (Fig. 4). P13 fractions prepared from KA31-1A WT cells expressing Tat1-EGFP, Hxt1-EGFP, or Pma1-EGFP were solubilized with 2% SDS or 1% DG. SDS disrupts protein complex formations by denaturation, while DG can solubilize membrane proteins without affecting the complexes. The proteins were separated by BN-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies. As expected from a previous study (9), all Pma1-EGFP migrated as a distinct high-molecular mass complex in extracts solubilized with DG. However, Pma1-EGFP solubilized with SDS migrated with an apparent molecular mass of ∼135 kDa, most likely corresponding to its monomeric protein, which has a predicted molecular mass of 126.6 kDa. Both Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP were mainly detected as dimeric bands of ∼135 kDa when solubilized with DG, but when solubilized with SDS both proteins were detected as monomeric bands of ∼70 kDa. Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP solubilized with SDS were also detected as broad bands, which might reflect posttranslational modification of the proteins. These results indicate that the homo (hetero)-interaction of Pma1-EGFP was stronger than the interactions of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP. Although all Pma1 proteins formed oligomers, 35% of the Pma1 oligomers diffused in the plasma membrane very slowly (Table 3), indicating that the amount of oligomeric Pma1 is not correlated with that of immobile molecules. Therefore, the oligomer formation may cause the decrease in the lateral diffusion of Pma1 without increasing the amounts of the immobile molecules.

Fig. 4.

Oligomer formations of Tat1, Hxt1, and Pma1 in WT yeast cells. Whole-cell extracts from KA31-1A cells expressing Tat1-EGFP, Hxt1-EGFP, or Pma1-EGFP were prepared and subjected to differential centrifugation to yield P13 fractions. The P13 fractions were solubilized with 2% SDS or 1% DG. Protein extracts were separated by BN-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GFP antibodies. O, oligomer; D, dimer; M, monomer.

The lateral diffusion of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP is affected by C4-OH of LCB and/or C2-OH of VLCFA

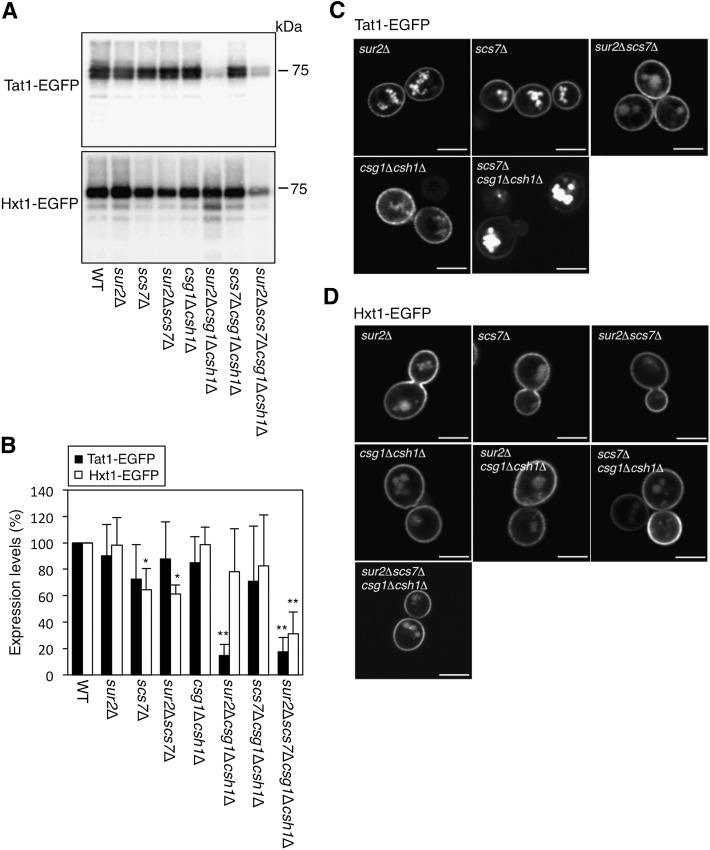

Because the lateral diffusion of Pma1-EGFP was very slow and its measurement and analysis by FRAP were difficult, Pma1-EGFP was excluded from further FRAP analysis. Instead, we expressed Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP in a series of mutants, compared the protein expression by immunoblotting, and observed their subcellular localization using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5). Unexpectedly, in our experiments, the amount of endogenous Pma1 (loading control) varied somewhat with the sample preparation, particularly in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant (data not shown) for unknown reasons, although that of Hxt1-EGFP did not. Thus, we normalized the amounts of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP using only the total protein concentrations. These experiments were performed more than three times independently. The protein expression and localization of Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δ, scs7Δ, sur2Δscs7Δ, and csg1Δcsh1Δ mutants were similar to those observed for WT cells (Fig. 5A–C). However, the amounts of Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants were markedly decreased compared with those in the WT cells (Fig. 5A, B), and Tat1-EGFP was barely detectable by fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). In the scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, Tat1-EGFP accumulated in intracellular membranes, such as endosomes, without altering its protein expression (Fig. 5C). On the other hand, Hxt1-EGFP mainly localized in the plasma membrane in all mutants, even though the protein expression of Hxt1-EGFP in the scs7Δ, sur2Δscs7Δ, and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants was decreased (Fig. 5A, B, D).

Fig. 5.

The localization and expression patterns of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants. The protein expression (A, B) and subcellular localizations (C, D) of Tat1-EGFP or Hxt1-EGFP in KA31-1A (WT), SUY12 (sur2Δ), SUY16 (scs7Δ), SUY359 (sur2Δscs7Δ), SUY65 (csg1Δcsh1Δ), SUY54 (scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ), or SUY434 (sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ) cells are presented. The P13 fractions of WT and mutant cells were prepared and the equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP were detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies and quantified with ImageJ software (A, B). The quantitative data are expressed as mean values with SD from more than three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 versus WT cells. The localizations were observed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (C, D). The white lines indicate 5 μm.

We examined the lateral diffusion of Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δ, scs7Δ, sur2Δscs7Δ, and csg1Δcsh1Δ mutants using FRAP analyses (Fig. 6). The fluorescence recovery of Tat1-EGFP decreased only in the sur2Δ mutant as compared with that in WT cells. Exponential approximation of the fluorescence recovery curves indicated that Tat1-EGFP presented as two diffusing components in this mutant (Table 4). The slow-t1/2 for Tat1-EGFP significantly increased in the sur2Δ mutant, but the percentage of Mf did not change. Because the t1/2 and Mf for Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δscs7Δ mutant were similar to those in WT cells, it is suggested that the decrease in the lateral diffusion of Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δ mutant causes an accumulation of B′ species of complex sphingolipids.

TABLE 4.

Exponential approximation of Tat1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants

| t1/2 (min) | Mf (%) | |||

| Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | |

| WTa | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 42.7 ± 4.8 | 9.3 ± 1.4 |

| sur2Δ | 7.3 ± 1.3b | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 41.3 ± 5.3 | 10.5 ± 0.8 |

| scs7Δ | 4.7 ± 0.69 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 42.0 ± 4.1 | 9.0 ± 0.8 |

| sur2Δscs7Δ | 5.2 ± 0.43 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 46.7 ± 5.8 | 8.5 ± 0.8 |

| csg1Δcsh1Δ | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 45.9 ± 9.0 | 9.9 ± 1.5 |

This data is the same as Table 2.

P < 0.05 as compared with WT.

Next, we performed FRAP analyses of Hxt1-EGFP using all mutants (Fig. 7). The fluorescence recovery of Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δ mutant decreased, while recovery in the scs7Δ and sur2Δscs7Δ mutants was similar to that in the WT cells. However, the results of exponential approximation using these data were different from those using recovery curves for Tat1-EGFP. The slow-t1/2 of Hxt1-EGFP in the scs7Δ and sur2Δscs7Δ mutants also increased slightly (Table 5). These results indicate that the defect in the C-species decreased the speed of the lateral diffusion of Hxt1-EGFP. Moreover, the SUR2 and/or SCS7 mutations in the csg1Δcsh1Δ background caused a decrease in the fluorescence recovery of Hxt1-EGFP. Notably, the fluorescence recovery of Hxt1-EGFP dramatically decreased in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant (Fig. 7E). Exponential approximation revealed that Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was present as one diffusing component, like Pma1-EGFP, and the percentage of Mf was decreased to 17.4 ± 3.7% (Table 5). The t1/2 for Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant increased about 1.5-fold compared with the slow-t1/2 for Hxt1-EGFP in the WT cells (Table 5). Therefore, most Hxt1-EGFP proteins in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant are immobile molecules, and the speed of lateral diffusion for the mobile molecules is very slow. On the other hand, Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant presented as two diffusing components, retaining 36.9 ± 10.6% of slow mobile molecules, but its slow-t1/2 prominently increased (Table 5). As shown Table 2, the amount of ergosterol in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, but not the sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, was also decreased compared with that in WT cells. Taken together, these results suggest that the defect of C4-OH and the reduction of ergosterol content cause the loss of a fast component and a decrease in the percentage of mobile molecules. The speed of the lateral diffusion of Hxt1-EGFP was probably decreased by the defects in C4-OH and C2-OH.

TABLE 5.

Exponential approximation of Hxt1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants

| t1/2 (min) | Mf (%) | |||

| Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | |

| WTa | 4.74 ± 0.69 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 42.2 ± 5.8 | 7.1 ± 1.7 |

| sur2Δ | 8.67 ± 0.85b | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 36.4 ± 4.5 | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| scs7Δ | 6.04 ± 0.79b | 0.06 ± 0.02b | 45.3 ± 5.1d | 5.4 ± 0.8 |

| sur2Δscs7Δ | 7.15 ± 0.72b | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 51.1 ± 4.1e | 5.6 ± 0.5 |

| csg1Δcsh1Δ | 5.21 ± 1.63 | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 47.7 ± 3.1 | 6.3 ± 0.7 |

| sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 7.54 ± 1.45c | 17.4 ± 3.7c | ||

| scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 6.55 ± 1.19b | 0.06 ± 0.02b | 37.3 ± 3.6 | 4.6 ± 0.3 |

| sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ | 14.2 ± 2.7b | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 36.9 ± 10.6 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

This data is the same as Table 2.

P < 0.05 as compared with WT.

P < 0.05 as compared with slow-t1/2 or slow-Mf of WT.

P < 0.06 as compared with slow-Mf of sur2Δ.

P < 0.05 as compared with slow-Mf of sur2Δ.

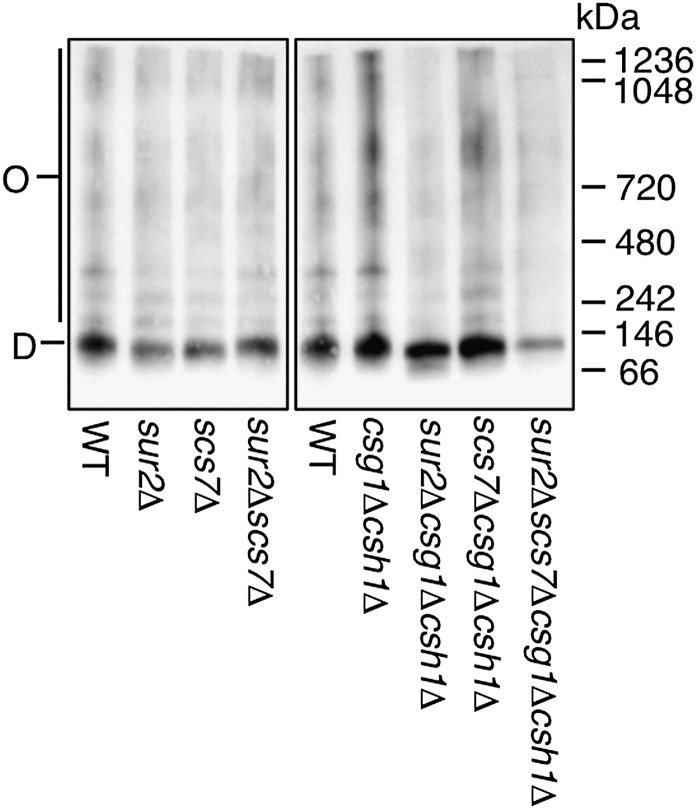

Because the number of diffusing components of Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant decreased and the speed was extremely slow, we examined whether Hxt1-EGFP in this mutant also forms oligomeric complexes (similar to those for Pma1) in the plasma membrane. P13 fractions prepared from each mutant expressing Hxt1-EGFP were solubilized with 1% DG. The proteins were separated by BN-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 8). The intensity of oligomer bands of Hxt1-EGFP was not increased in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants, but the total protein amount in the sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was also downregulated. The formation of Hxt1-EGFP oligomers in the other mutants was similar to that observed in the WT cells. These results suggest that the SUR2 mutation in csg1Δcsh1Δ background does not greatly affect the oligomeric states of Hxt1-EGFP. Thus, it raises the possibility that reductions in the lateral diffusion of Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ or sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant reflect a decrease in membrane fluidity.

Fig. 8.

Oligomer formation of Hxt1-EGFP in a series of yeast mutants. P13 fractions were prepared from WT and mutant cells expressing Hxt1-EGFP and solubilized with 1% DG. Proteins were then separated by BN-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GFP antibodies. O, oligomer; D, dimer.

DISCUSSION

In mammals, glycosphingolipids are hydroxylated on the C-2 and/or C-4 position of the ceramide moiety in specific tissues (brain, small intestine, and skin). However, the biological significance of the hydroxylation remains unclear. In S. cerevisiae, complex sphingolipids corresponding to mammalian glycosphingolipids are mainly hydroxylated on the C-2 and C-4 positions of the ceramide. To understand the roles of these hydroxyl groups, we examined the cell growth and membrane fluidity of yeast mutants lacking the hydroxyl groups. In the present study, we established sur2Δ (absence of C4-OH) and/or scs7Δ (absence of C2-OH) mutants in WT and csg1Δcsh1Δ backgrounds. The total amounts of complex sphingolipids, phospholipids, and ergosterol in these mutants were similar to those found in WT cells, although the amount of ergosterol in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was slightly decreased compared with that of the WT cells (Fig. 1; Table 2). Integration of experimental information and computational approaches opens up a new opportunity for understanding of the dynamic regulation of the entire sphingolipid metabolism (34, 35). As a heat-stress response in yeast, Chen et al. (36) reported that the activities of all enzymes involved in sphingolipid metabolism rapidly increased in the first few minutes of heat stress. The whole biosynthetic pathway of sphingolipids was shut down after 6 min of heat stress, and after 30 min the metabolite levels returned to the optimal levels. It is worthwhile to elucidate whether the sur2Δ, scs7Δ, csg1Δ, and csh1Δ mutations have an influence on the entire sphingolipid metabolism using the dynamic mathematic model. The growth of sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants, which possess IPC-B′/IPC-A and IPC-A, respectively, was significantly decreased when cultured in SC medium (chemically defined medium) relative to YPD cultures (nutritionally enriched medium) (Fig. 2A, B). This suggests that the extension of both the hydrophilic head group and the C4-OH are necessary for effective growth in limited nutrient conditions.

Studies of model membranes show that liquid-disordered (Ld) and liquid-ordered (Lo) phases coexist in ternary mixtures of sterol (e.g., ergosterol), sphingolipids, and glycerolipids (e.g., dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine) (37–41). While the Ld phase is a fluid state, the Lo phase is an intermediate state between gel and liquid crystal phases, characterized by tight packing and rapid lateral diffusion. FRAP analyses of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP indicate that these proteins reside in the plasma membrane as ∼50% of immobile molecules, ∼40% of mobile molecules (slow), and ∼10% of mobile molecules (fast) (Fig. 3; Table 3). We assume that mobile molecules (slow) and mobile molecules (fast) exist in the Lo and Ld domains, respectively. Then, what do immobile molecules arise from? One possibility is that the immobile molecules arise from the restricted mobility caused by their oligomer formation or by the interaction with other proteins. However, this might be inconstant with the findings that the large oligomeric Pma1 complex diffuses in the plasma membrane (Fig. 3; Table 3). In addition, the dimer/oligomer ratio of the Hxt1 remains constant in a series of the mutants (Fig. 8), although the immobile molecules are increased by the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutation. Another possibility is that the solid-like gel (Lβ) phase, where the membrane fluidity is extremely low, exists in the yeast plasma membrane. It is known that the high melting temperature lipids form a tightly packed Lβ phase in the absence of sterol. It remains unclear to what extent the Lβ domain exists in plasma membrane because the numerous membrane proteins in living cells could prevent the membrane from packing (32, 42). The amount of immobile molecules markedly increased in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant with the decrease in ergosterol content containing the P13 fraction (Fig. 7; Tables 2, 3). Considering the phase diagrams of ternary mixture (39, 41, 43–45), a sufficient degree of ergosterol depletion would cause the transition from the Lo phase to the Lβ phase. The ergosterol content in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was decreased by ∼20–30% relative to WT cells. Although it is unclear whether such a decrease in ergosterol content alone renders an increase of the Lβ domain in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, the loss of C4-OH might have a promotive effect on the formation of the Lβ domain caused by the decrease in ergosterol content.

Moreover, we speculate that the presence of C4-OH and C2-OH prevents the aggregation of complex sphingolipids in the Lo phase and is important for maintaining plasma membrane fluidity. Decreased membrane fluidity in cells lacking C4-OH or C2-OH is unexpected because several biophysical studies have demonstrated that C4-OH and C2-OH enhance the interaction between sphingolipids by hydrogen bonding (46–48). However, these studies were performed in the absence of proteins, using only synthetic sphingolipids. As described above, lipid-lipid interaction is prevented by membrane proteins in the presence of sterol. Therefore, it raises the possibility that membrane proteins enter into the complex sphingolipid platforms to maintain proper membrane fluidity in living cells. We speculate that C4-OHs and C2-OHs are needed to interact with the plasma membrane proteins via hydrogen bonds. While C4-OH acts as a donor and acceptor of hydrogen bonding in lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions, C2-OH only acts as a donor. Hence, the loss of C4-OH has a more significant effect on membrane fluidity. Because the loss of both C4-OH and C2-OH had a more critical effect on membrane fluidity in the csg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, which expresses only IPCs, than in the WT strain, M(IP)2C and/or MIPC could potentially act to prevent aggregation of the complex sphingolipids due to steric repulsion between hydrophilic head groups (Fig. 7C, G). We also assume that decreases in cell growth of the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants in SC medium are caused by dysfunction in membrane proteins followed by reduced membrane fluidity.

FRAP analysis of Pil1-GFP-labeled MCC demonstrated no detectable fluorescence recovery over 20 min, indicating that MCCs are stable ultrastructural assemblies (12). Can1-GFP fluorescence in MCC patches and non-MCC areas recovered, on average, with a t1/2 of 5.72 ± 0.28 min and 1.22 ± 0.08 min, respectively (49). Can1 mainly localizes in the MCC, but continuously crosses between MCC patches and non-MCC areas. Brach, Specht, and Kaksonen (49) assumed that the mobility of Can1-GFP in non-MCC areas corresponded to the molecules existing in the MCP. We found that in FRAP analysis both Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP present as two diffusing components (Table 3). The t1/2 of the slow components is similar to that of Can1-GFP in the MCC. However, the t1/2 of the fast components is dramatically faster than that of Can1-GFP in non-MCC areas. Because complex sphingolipids possessing saturated fatty acids are abundant in the MCP, its membrane fluidity ought to be more slow, like that of the MCC. Thus, we concluded that the fast components correspond to molecules existing in glycerolipid-enriched domains (Ld domain), although it remains unclear what the t1/2 of Can1-GFP in non-MCC areas actually means. The slow-t1/2 of Hxt1-EGFP and Tat1-EGFP might reflect the mobility of molecules localized in both the MCC and MCP.

The protein expression of Tat1-EGFP was remarkably reduced in the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ and sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutants. Considering the FRAP analyses using Hxt1-EGFP, the membrane fluidity in these mutants would be decreased compared with that in WT cells. Hydrostatic pressure at nonlethal levels (250 kg·cm−2) reportedly stimulates ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Tat1 (50). Increasing hydrostatic pressure increases the membrane order and reduces lateral diffusion in both artificial and biological membranes, causing decreased membrane fluidity (51). Therefore, our data also support the hypothesis that the degradation of Tat1 was induced by decreased membrane fluidity. However, Tat1-EGFP in the scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant accumulated in intracellular compartments without altering its protein expression. Because Tat1-EGFP in the sur2Δscs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant was probably degraded in vacuole and was not detectable in intracellular compartments, accumulated IPC-B in the scs7Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant may inhibit transport from endosomes to vacuoles. The localization and stability of Pma1 are abnormal in the lcb1-100 (which is defective in de novo sphingolipid synthesis), tsc3Δ, elo2Δ, elo3Δ, and tsc13Δ mutants (52, 53). In addition, the lcb1-100 mutant shows defects in localization of Can1 (H+/arginine antiporter) and Nha1 (Na+/H+ antiporter), and the elo3Δ mutant shows a defect in localization of Gas1 (GPI-anchored protein) (5, 54, 55). These results suggest that the VLCFA portion is necessary for protein sorting to the cell surface, but the specificity of membrane proteins is not clear. As this molecular mechanism, it has been proposed that VLCFAs have a role in stabilizing the membrane curvature in vesicular trafficking (56). Thus, the formation of membrane curvature in endosomes may be affected by the accumulation of IPC-B.

During differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes, the FA2H gene level markedly increases (57). In mature adipocytes, the depletion of FA2H (3T3-L1/FA2H) causes the increase of lateral diffusion of lipids labeled with Alex488-conjugated cholera toxin subunit B (probably GM1), suggesting that C2-OH enhances the lipid packing (57). Because glycosphingolipids containing C4-OH are produced only in skin, small intestine, and kidney (22), mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes probably possess only glycosphingolipids containing C2-OH. In addition, 3T3-L1 adipocytes have glycosphingolipids with several glycans, such as GM3, GM1, and GD1a (58). Accordingly, the membrane compositions of the mature 3T3-L1 and 3T3-L1/FA2H adipocytes correspond to those of sur2Δ and sur2Δscs7Δ mutants, respectively. Our data also indicate that the fluorescence recovery of Tat1-EGFP and Hxt1-EGFP in the sur2Δscs7Δ mutant is slightly higher than that in the sur2Δ mutant (Figs. 6, 7). Therefore, in the absence of C4-OH background, the accumulation of C2-OH may lead to the enhancement of lipid packing.

In the mammalian nervous system, nerve conduction is greatly facilitated by myelin, a lipid-rich membrane that covers the axon (59). Myelin contributes half of brain white matter dry weight. It has a low water content and a dry chemical composition of 70% lipids and 30% proteins (59). Myelin is particularly rich in galactosylceramide (GalCer) and its sulfated form, sulfatide. In GalCer and sulfatide, hydrophilic head groups are simple structures similar to the complex sphingolipids in the csg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, and more than half of GalCer and sulfatide contain C2-OH (60). No other mammalian tissues contain such high concentrations of hydroxylated sphingolipids. Moreover, because GalCer and sulfatide containing C4-OH are not detected in myelin (61), we speculate that the composition of myelin membrane corresponds to that of the sur2Δcsg1Δcsh1Δ mutant, and the membrane fluidity is very low. Mutations in the human FA2H gene are associated with leukodystrophy, which presents with myelin degeneration (28, 29). In FA2H-deficient mice, structurally and functionally normal myelin can be formed, but its long-term maintenance is strikingly impaired (61). In contrast, transgenic mice overexpressing UDP-galactose:ceramide galactosyltransferase have reduced levels of hydroxylated GalCer, and nonhydroxylated GalCer is increased (62). Myelin is unstable in these mice, which develop progressive demyelination. These results suggest that the balance of hydroxylated and nonhydroxylated GalCer is important for long-term maintenance of myelin. Considering our data, we speculate that the disruption of such balance leads to a change in membrane fluidity and to myelin degeneration. Future studies should clarify whether our findings apply to glycosphingolipids in mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. H. Matsuki for valuable discussions and Dr. A. Sweeney for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- BN-PAGE

- blue native PAGE

- DG

- digitonin

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- GalCer

- galactosylceramide

- Hxt1

- hexose transporter 1

- Hxt1-EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein-tagged hexose transporter 1

- IPC

- inositol phosphorylceramide

- LCB

- long-chain base

- Ld

- liquid-disordered

- Lo

- liquid-ordered

- Lβ

- solid-like gel

- MCC

- membrane compartment containing Can1

- MCP

- membrane compartment containing Pma1

- MCT

- membrane compartment containing target of rapamycin kinase complex 2

- Mf

- mobile fraction

- MIPC

- mannnosylinositol phosphorylceramide

- M(IP)2C

- mannosyldiinositol phosphorylceramide

- OD600

- optical density measured at 600 nm

- SC

- synthetic complete

- Tat1

- tryptophan transporter 1

- VLCFA

- very long-chain fatty acid

- YPD

- medium containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose

This work was supported by KAKENHI (21770148 and 24780077) and a grant from the Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (2013-2017).

REFERENCES

- 1.van Meer G., Voelker D. R., Feigenson G. W. 2008. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9: 112–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons K., Toomre D. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1: 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levental I., Grzybek M., Simons K. 2010. Greasing their way: lipid modifications determine protein association with membrane rafts. Biochemistry. 49: 6305–6316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lingwood D., Simons K. 2010. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 327: 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malínská K., Malinský J., Opekarová M., Tanner W. 2003. Visualization of protein compartmentation within the plasma membrane of living yeast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14: 4427–4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malinska K., Malinsky J., Opekarova M., Tanner W. 2004. Distribution of Can1p into stable domains reflects lateral protein segregation within the plasma membrane of living S. cerevisiae cells. J. Cell Sci. 117: 6031–6041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berchtold D., Walther T. C. 2009. TORC2 plasma membrane localization is essential for cell viability and restricted to a distinct domain. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20: 1565–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaigg B., Toulmay A., Schneiter R. 2006. Very long-chain fatty acid-containing lipids rather than sphingolipids per se are required for raft association and stable surface transport of newly synthesized plasma membrane ATPase in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 34135–34145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M. C., Hamamoto S., Schekman R. 2002. Ceramide biosynthesis is required for the formation of the oligomeric H+-ATPase Pma1p in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 22395–22401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagnat M., Keranen S., Shevchenko A., Simons K. 2000. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97: 3254–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagnat M., Chang A., Simons K. 2001. Plasma membrane proton ATPase Pma1p requires raft association for surface delivery in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12: 4129–4138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walther T. C., Brickner J. H., Aguilar P. S., Bernales S., Pantoja C., Walter P. 2006. Eisosomes mark static sites of endocytosis. Nature. 439: 998–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossmann G., Opekarova M., Malinsky J., Weig-Meckl I., Tanner W. 2007. Membrane potential governs lateral segregation of plasma membrane proteins and lipids in yeast. EMBO J. 26: 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakomori S. I. 2008. Structure and function of glycosphingolipids and sphingolipids: recollections and future trends. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1780: 325–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagiec M. M., Nagiec E. E., Baltisberger J. A., Wells G. B., Lester R. L., Dickson R. C. 1997. Sphingolipid synthesis as a target for antifungal drugs. Complementation of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase defect in a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the AUR1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 9809–9817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uemura S., Kihara A., Inokuchi J., Igarashi Y. 2003. Csg1p and newly identified Csh1p function in mannosylinositol phosphorylceramide synthesis by interacting with Csg2p. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 45049–45055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson R. C., Nagiec E. E., Wells G. B., Nagiec M. M., Lester R. L. 1997. Synthesis of mannose-(inositol-P)2-ceramide, the major sphingolipid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, requires the IPT1 (YDR072c) gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 29620–29625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beeler T. J., Fu D., Rivera J., Monaghan E., Gable K., Dunn T. M. 1997. SUR1 (CSG1/BCL21), a gene necessary for growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the presence of high Ca2+ concentrations at 37 degrees C, is required for mannosylation of inositol-phosphorylceramide. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255: 570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aerts A. M., Francois I. E., Bammens L., Cammue B. P., Smets B., Winderickx J., Accardo S., De Vos D. E., Thevissen K. 2006. Level of M(IP)2C sphingolipid affects plant defensin sensitivity, oxidative stress resistance and chronological life-span in yeast. FEBS Lett. 580: 1903–1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haak D., Gable K., Beeler T., Dunn T. 1997. Hydroxylation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ceramides requires Sur2p and Scs7p. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 29704–29710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alderson N. L., Rembiesa B. M., Walla M. D., Bielawska A., Bielawski J., Hama H. 2004. The human FA2H gene encodes a fatty acid 2-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 48562–48568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizutani Y., Kihara A., Igarashi Y. 2004. Identification of the human sphingolipid C4-hydroxylase, hDES2, and its up-regulation during keratinocyte differentiation. FEBS Lett. 563: 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omae F., Miyazaki M., Enomoto A., Suzuki A. 2004. Identification of an essential sequence for dihydroceramide C-4 hydroxylase activity of mouse DES2. FEBS Lett. 576: 63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omae F., Miyazaki M., Enomoto A., Suzuki M., Suzuki Y., Suzuki A. 2004. DES2 protein is responsible for phytoceramide biosynthesis in the mouse small intestine. Biochem. J. 379: 687–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alderson N. L., Maldonado E. N., Kern M. J., Bhat N. R., Hama H. 2006. FA2H-dependent fatty acid 2-hydroxylation in postnatal mouse brain. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2772–2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enomoto A., Omae F., Miyazaki M., Kozutsumi Y., Yubisui T., Suzuki A. 2006. Dihydroceramide:sphinganine C-4-hydroxylation requires Des2 hydroxylase and the membrane form of cytochrome b5. Biochem. J. 397: 289–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uchida Y., Hama H., Alderson N. L., Douangpanya S., Wang Y., Crumrine D. A., Elias P. M., Holleran W. M. 2007. Fatty acid 2-hydroxylase, encoded by FA2H, accounts for differentiation-associated increase in 2-OH ceramides during keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 13211–13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edvardson S., Hama H., Shaag A., Gomori J. M., Berger I., Soffer D., Korman S. H., Taustein I., Saada A., Elpeleg O. 2008. Mutations in the fatty acid 2-hydroxylase gene are associated with leukodystrophy with spastic paraparesis and dystonia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83: 643–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dick K. J., Eckhardt M., Paisan-Ruiz C., Alshehhi A. A., Proukakis C., Sibtain N. A., Maier H., Sharifi R., Patton M. A., Bashir W., et al. 2010. Mutation of FA2H underlies a complicated form of hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG35). Hum. Mutat. 31: E1251–E1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klose C., Ejsing C. S., Garcia-Saez A. J., Kaiser H. J., Sampaio J. L., Surma M. A., Shevchenko A., Schwille P., Simons K. 2010. Yeast lipids can phase-separate into micrometer-scale membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 30224–30232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abe F., Hiraki T. 2009. Mechanistic role of ergosterol in membrane rigidity and cycloheximide resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1788: 743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aresta-Branco F., Cordeiro A. M., Marinho H. S., Cyrne L., Antunes F., de Almeida R. F. 2011. Gel domains in the plasma membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: highly ordered, ergosterol-free, and sphingolipid-enriched lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 5043–5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan X. L., Souza C. M., Pichler H., Dewhurst G., Schaad O., Kajiwara K., Wakabayashi H., Ivanova T., Castillon G. A., Piccolis M., et al. 2009. Functional interactions between sphingolipids and sterols in biological membranes regulating cell physiology. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20: 2083–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez-Vasquez F., Sims K. J., Hannun Y. A., Voit E. O. 2004. Integration of kinetic information on yeast sphingolipid metabolism in dynamical pathway models. J. Theor. Biol. 226: 265–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez-Vasquez F., Sims K. J., Cowart L. A., Okamoto Y., Voit E. O., Hannun Y. A. 2005. Simulation and validation of modelled sphingolipid metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 433: 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen P. W., Fonseca L. L., Hannun Y. A., Voit E. O. 2013. Coordination of rapid sphingolipid responses to heat stress in yeast. PLOS Comput. Biol. 9: e1003078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dietrich C., Bagatolli L. A., Volovyk Z. N., Thompson N. L., Levi M., Jacobson K., Gratton E. 2001. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys. J. 80: 1417–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahya N., Scherfeld D., Bacia K., Poolman B., Schwille P. 2003. Probing lipid mobility of raft-exhibiting model membranes by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 28109–28115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veatch S. L., Keller S. L. 2003. Separation of liquid phases in giant vesicles of ternary mixtures of phospholipids and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85: 3074–3083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samsonov A. V., Mihalyov I., Cohen F. S. 2001. Characterization of cholesterol-sphingomyelin domains and their dynamics in bilayer membranes. Biophys. J. 81: 1486–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao J., Wu J., Heberle F. A., Mills T. T., Klawitter P., Huang G., Costanza G., Feigenson G. W. 2007. Phase studies of model biomembranes: complex behavior of DSPC/DOPC/cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1768: 2764–2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaiser H. J., Surma M. A., Mayer F., Levental I., Grzybek M., Klemm R. W., Da Cruz S., Meisinger C., Muller V., Simons K., et al. 2011. Molecular convergence of bacterial and eukaryotic surface order. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 40631–40637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyholm T. K., Lindroos D., Westerlund B., Slotte J. P. 2011. Construction of a DOPC/PSM/cholesterol phase diagram based on the fluorescence properties of trans-parinaric acid. Langmuir. 27: 8339–8350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.London E. 2005. How principles of domain formation in model membranes may explain ambiguities concerning lipid raft formation in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1746: 203–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veatch S. L., Keller S. L. 2005. Miscibility phase diagrams of giant vesicles containing sphingomyelin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94: 148101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boggs J. M. 1987. Lipid intermolecular hydrogen bonding: influence on structural organization and membrane function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 906: 353–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boggs J. M., Koshy K. M., Rangaraj G. 1988. Influence of structural modifications on the phase behavior of semi-synthetic cerebroside sulfate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 938: 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Löfgren H., Pascher I. 1977. Molecular arrangements of sphingolipids. The monolayer behaviour of ceramides. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 20: 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brach T., Specht T., Kaksonen M. 2011. Reassessment of the role of plasma membrane domains in the regulation of vesicular traffic in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 124: 328–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abe F., Iida H. 2003. Pressure-induced differential regulation of the two tryptophan permeases Tat1 and Tat2 by ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 and its binding proteins, Bul1 and Bul2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 7566–7584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hazel J. R., Williams E. E. 1990. The role of alterations in membrane lipid composition in enabling physiological adaptation of organisms to their physical environment. Prog. Lipid Res. 29: 167–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaigg B., Timischl B., Corbino L., Schneiter R. 2005. Synthesis of sphingolipids with very long chain fatty acids but not ergosterol is required for routing of newly synthesized plasma membrane ATPase to the cell surface of yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 22515–22522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montefusco D. J., Matmati N., Hannun Y. A. 2014. The yeast sphingolipid signaling landscape. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 177: 26–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitsui K., Hatakeyama K., Matsushita M., Kanazawa H. 2009. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Na+/H+ antiporter Nha1p associates with lipid rafts and requires sphingolipid for stable localization to the plasma membrane. J. Biochem. 145: 709–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eisenkolb M., Zenzmaier C., Leitner E., Schneiter R. 2002. A specific structural requirement for ergosterol in long-chain fatty acid synthesis mutants important for maintaining raft domains in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13: 4414–4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Obara K., Kojima R., Kihara A. 2013. Effects on vesicular transport pathways at the late endosome in cells with limited very long-chain fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 54: 831–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo L., Zhou D., Pryse K. M., Okunade A. L., Su X. 2010. Fatty acid 2-hydroxylase mediates diffusional mobility of raft-associated lipids, GLUT4 level, and lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 25438–25447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tagami S., Inokuchi Ji J., Kabayama K., Yoshimura H., Kitamura F., Uemura S., Ogawa C., Ishii A., Saito M., Ohtsuka Y., et al. 2002. Ganglioside GM3 participates in the pathological conditions of insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 3085–3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morell P., Quarles R. H. 1999. Myelin formation, structure and biochemistry. In Basic Neurochemistry. G. J. Siegel, B. W. Agranoff, S. K. Fisher, et al., editors. Lippincott-Raven, New York. 69–94.

- 60.Norton W. T., Cammer W. 1984. Isolation and characterization of myelin. In Myelin. P. Morell, editor. Plenum Press, New York. 147–195.

- 61.Zöller I., Meixner M., Hartmann D., Büssow H., Meyer R., Gieselmann V., Eckhardt M. 2008. Absence of 2-hydroxylated sphingolipids is compatible with normal neural development but causes late-onset axon and myelin sheath degeneration. J. Neurosci. 28: 9741–9754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fewou S. N., Bussow H., Schaeren-Wiemers N., Vanier M. T., Macklin W. B., Gieselmann V., Eckhardt M. 2005. Reversal of non-hydroxy:alpha-hydroxy galactosylceramide ratio and unstable myelin in transgenic mice overexpressing UDP-galactose:ceramide galactosyltransferase. J. Neurochem. 94: 469–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Irie K., Takase M., Lee K. S., Levin D. E., Araki H., Matsumoto K., Oshima Y. 1993. MKK1 and MKK2, which encode Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase homologs, function in the pathway mediated by protein kinase C. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 3076–3083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]