Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major life-threatening complication of diabetes. Renal lesions affect glomeruli and tubules, but the pathogenesis is not completely understood. Phospholipids and glycolipids are molecules that carry out multiple cell functions in health and disease, and their role in DN pathogenesis is unknown. We employed high spatial resolution MALDI imaging MS to determine lipid changes in kidneys of eNOS−/− db/db mice, a robust model of DN. Phospholipid and glycolipid structures, localization patterns, and relative tissue levels were determined in individual renal glomeruli and tubules without disturbing tissue morphology. A significant increase in the levels of specific glomerular and tubular lipid species from four different classes, i.e., gangliosides, sulfoglycosphingolipids, lysophospholipids, and phosphatidylethanolamines, was detected in diabetic kidneys compared with nondiabetic controls. Inhibition of nonenzymatic oxidative and glycoxidative pathways attenuated the increase in lipid levels and ameliorated renal pathology, even though blood glucose levels remained unchanged. Our data demonstrate that the levels of specific phospho- and glycolipids in glomeruli and/or tubules are associated with diabetic renal pathology. We suggest that hyperglycemia-induced DN pathogenic mechanisms require intermediate oxidative steps that involve specific phospholipid and glycolipid species.

Keywords: kidney, glomerulus, mass spectrometry, imaging, oxidative stress, diabetes, glucose

The global epidemic of diabetes is a major health problem. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) can develop in about 1/3 of diabetic individuals and is characterized by specific glomerular and tubular lesions in the kidney. These lesions are associated with progression to end stage renal disease with subsequent requirement for renal dialysis and transplantation (1). Despite the significance of DN, there is still incomplete understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms, particularly those underlying the differential susceptibility to DN.

Lipids may play a role in DN, but to date, the research focus has been on neutral lipids such as triacylglycerols and cholesterol (2). Phospho- and glycolipids are two major classes of lipid molecules that carry out many biological functions ranging from regulation of physical properties of cellular membranes to cell signaling (3, 4). In diabetes, changes in the levels of these lipids in blood and tissues cause dysregulation of different cellular processes associated with pathogenesis (3, 5–9). Thus, phospho- and glycolipids may have a role in DN.

Uncovering molecular events that define mechanisms of susceptibility and progression in DN requires knowledge of the identity and spatial localization of biomolecules within glomerular and tubular areas of the kidney. Such knowledge can be obtained using MALDI imaging MS (IMS), a rapidly advancing technology that acquires molecular information from thin tissue sections in a spatially-defined manner (10, 11). The levels and spatial localization of biomolecules can be detected from a single tissue section without the need for specific antibodies or a priori knowledge of what molecules are present. For an imaging experiment, a chemical matrix to aid in the absorption of laser energy and ionization is applied uniformly over the sample. The laser is moved in a raster pattern and a spectrum is collected at every pixel in an ordered array across the tissue. Data can then be displayed as molecular maps of the spatial localization of given m/z values throughout the tissue. Molecular identification can be performed directly on the tissue section by MS/MS analysis.

The present study is the first report of the application of MALDI IMS to investigate molecular changes in renal glomerular and tubular phospho- and glycolipids in DN. We utilized a set of experimental tools: a robust DN mouse model, which develops renal lesions comparable to those found in human disease (12); a high spatial resolution MALDI IMS technology; and pyridoxamine (PM), which was employed to elucidate whether hyperglycemia-induced oxidative pathways play a role in phospho- and glycolipid changes relevant to DN. PM is an inhibitor of oxidative and glycoxidative reactions and has been shown to act via sequestration of redox active metal ions, scavenging of reactive carbonyl compounds, and scavenging of hydroxyl radical both in vitro and in vivo (13–18). We determined molecular changes at the level of a single glomerulus or tubule, which has not been achieved in the previous studies of renal tissues using MALDI IMS (19–21). Our data demonstrated that the levels of specific phospho- and glycolipids in glomeruli and/or tubules of the kidney are associated with diabetic renal pathology. Inhibition of glycoxidative pathways, without lowering hyperglycemia, ameliorated lipid levels and renal lesions. We suggest that hyperglycemia-induced DN pathogenic mechanisms require intermediate oxidative steps that involve phospho- and glycolipids.

METHODS

Animal studies

Animal experiments were performed at Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited animal facilities at Vanderbilt University Medical Center according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved experimental protocol. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility and given standard chow (Lab Diet 5015; PMI Nutrition International, Richmond, IN) and water ad libitum. Upon development of hyperglycemia (about 6 weeks of age), eNOS−/− C57BLKS db/db mice were randomized according to body weight and assigned to either diabetic or diabetic/PM treatment groups. Mice in the diabetic/PM treatment group received PM in drinking water at a daily dose of 400 mg/kg body weight, based on previously published reports of PM protection from kidney injury in diabetic mice (22). To minimize possible chemical degradation of PM, a light-sensitive compound, fresh solutions were prepared twice a week and administered in water bottles wrapped in aluminum foil as previously described (23). PM treatment continued until the mice were euthanized at 22 weeks of age. The control group included wild-type C57BLKS mice. Kidneys were removed and either fixed for histological analyses by light and electron microscopy or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for IMS analyses.

Determination of blood glucose and urinary albumin excretion

Glucose levels were measured in blood collected from the tail vein using OneTouch glucometer and Ultra test strips (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA) as previously described (12, 24). Albumin and creatinine excretion was determined in spot urine collected from individually caged mice using Albuwell-M kits (Exocell Inc., Philadelphia, PA) as previously described (12, 24). The assay variability was <5% in duplicate measurements.

Histological analyses

Renal histology was assessed in mice at 22 weeks of age. The kidneys were removed and fixed overnight in 10% formalin at 4°C, and 3 μm-thick sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Jones’ silver staining. Histological evaluation by light microscopy was performed without knowledge of the identity of the various groups. A semi-quantitative index was used to evaluate the degree of glomerular mesangial expansion and sclerosis. Each glomerulus on a single section was graded from 0 to 3, where 0 represents no lesion, and 1, 2, and 3 represent mesangial matrix expansion or sclerosis involving <25, 25 to 50, and >50% of the glomerular tuft area, respectively (see supplementary Fig. II).

For electron microscopy, kidneys were cut into small tissue blocks (1 mm3) and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative with 0.1 mol/l cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. After postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide, tissues were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol preparations and embedded in epoxy resin (Poly/Bed 812 embedding media; Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were observed by transmission electron microscopy (H-7000; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 75 kV to determine tubular basement membrane and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickness.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical detection of fibronectin was performed using an anti-fibronectin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The kidney sections then were incubated using the avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase technique (Elite Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and staining was visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine.

MALDI MS

MALDI TOF lipid imaging.

Frozen kidneys were sectioned on a cryostat at 8 μm thickness, thaw mounted on conductive indium tin oxide-coated glass slides, and dried in a desiccator. The tissue sections were washed by dipping the slide in 50 mM ammonium formate at 4°C three times for five seconds each to remove salts and increase the sensitivity for lipid analysis (25). MALDI matrix was applied using a custom-built sublimation apparatus which uses reduced pressure and heat for vapor deposition of the MALDI matrix on to the sample slide (26) resulting in a uniform MALDI matrix coating over the tissue. 1,5-Diaminonaphthalene was sublimed at 110°C and 50 mTorr for 7 min. The resulting matrix coating contained 0.13 ± 0.02 mg 1,5-diaminonaphthalene/cm2. MALDI imaging experiments were performed in negative ion mode using a Bruker Ultraflextreme TOF mass spectrometer in reflectron geometry. Spectra were collected in the range of m/z 400–1,500 with 10 shots/spectra. Raster steps were taken in 10 μm stage increments and the laser spot size was also 10 μm in diameter as measured on a thin matrix coating. Each imaging experiment was run as a set containing a kidney section from each experimental group. Areas of the cortex were selected for imaging of approximately 20,000 pixels per kidney. Reproducibility of the IMS measurements within a single mouse was assessed by analyzing three separate sections from the same kidney. Lipid measurements by IMS were highly reproducible as shown in supplementary Fig. III. FlexImaging was used for image visualization.

MALDI FTICR lipid imaging.

Frozen kidneys were sectioned as above. 9-Aminoacridine MALDI matrix was applied by sublimation at 140°C and 50 mTorr for 12 min. The resulting matrix coating contained 1.1 ± 0.2 mg 9-aminoacridine/cm2. MALDI imaging experiments were performed in negative ion mode using a 9.4 T SolariX MALDI Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). Spectra were collected in the range of m/z of 400–1,500 with 500 shots/spectra. Image resolution was set at 40 μm or 10 μm. FlexImaging and DataAnalysis were used for image visualization and data analysis.

After all imaging experiments, the MALDI matrix was removed from the slides by immersion in 70% ethanol followed by 95% ethanol for 30 s each. Kidney sections were then stained with PAS and renal tissue structures were matched to MALDI IMS data via image overlay.

Lipid identification.

All lipids reported were identified using MS/MS fragmentation along with accurate mass data. Accurate masses were determined after imaging experiments by profiling an adjacent tissue section using MALDI FTICR MS. Phospholipid species were isolated and fragmented with the FTICR mass spectrometer using sustained off-resonance irradiation collision-induced dissociation (SORI-CID) for identification. Glycolipid species MS/MS fragmentation experiments were performed on a MALDI-LTQ-XL hybrid linear ion trap instrument (Thermo Scientific) using pulsed q-dissociation. The LIPID MAPS database (lipidmaps.org) was used to search the accurate mass data. Fragmentation patterns were interpreted manually along with tools from lipidmaps.org.

Relative quantitation of lipid levels.

For the MALDI imaging datasets, ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure the relative abundance of the lipid species of interest between experimental groups. Monochromatic TIFF images were exported from FlexImaging to ImageJ. Areas of interest were selected in each image as individual glomeruli, tubules, or the entire kidney section. Signal intensity was measured as the mean intensity per area of interest (i.e., glomeruli, tubules, or entire kidney cross-section). Glomerular and tubular signals were evaluated as single ions and the Amadori-phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) were evaluated as the ratio of the Amadori-PE signal to the unmodified PE signal.

Histology-directed IMS.

Frozen kidneys were sectioned as above and processed using a washing procedure described by Yang and Caprioli (27). Histology-directed IMS was performed as described previously (28), with some modifications. Kidney sections were stained with 0.5% cresyl violet for 30 s followed by an ethanol rinse. Coordinates of the individual glomeruli and tubules within the kidney sections were recorded using a Mirax slide scanner (Zeiss). Trypsin and the MALDI matrix were deposited using an automated acoustic robotic spotter (Portrait 630, Labcyte). Trypsin solution (76 ng/μl trypsin in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate/10% acetonitrile) was spotted on the tissue in single droplets (∼120 pL) for a total of 40 iterations. Proteolytic digestion was allowed to take place for 2 h. Subsequently, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid MALDI matrix (10 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 1:1 v/v mixture of acetonitrile and 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid) was robotically spotted on the trypsin-digested glomeruli. MALDI MS analyses of tryptic peptides were acquired on a Bruker UltrafleXtreme mass spectrometer in positive ion reflectron mode. Analysis was performed with 250 shots/spectra. Digestion peptide profiles from the glomeruli were acquired in the range of m/z 600–3,900. Peaks with significant intensity changes between the groups were manually selected for MS/MS analysis. MS/MS spectra were submitted to the MASCOT (Matrix Science) database search engine to match tryptic peptide sequences to their respective intact proteins (see supplementary Fig. IV). The intensity of the fibronectin peptide at m/z 1,906 was used to determine the relative deposition of fibronectin in glomeruli from different experimental groups (Fig. 2F). This increase in fibronectin deposition by IMS was consistent with that determined using the classical immunohistochemistry approach (supplementary Fig. V).

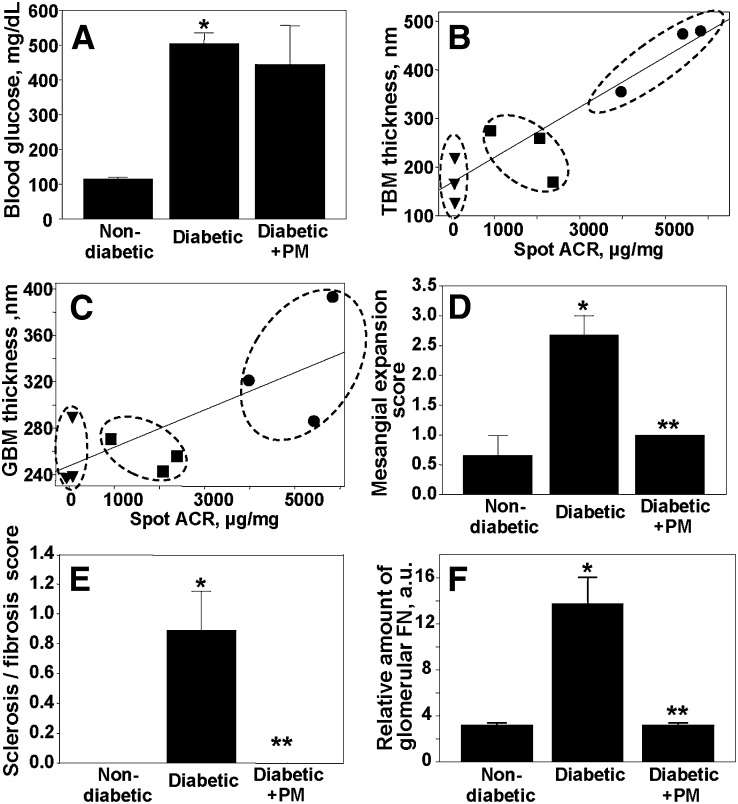

Fig. 2.

Renal injury and effect of PM treatment. Pathologic renal lesions were determined only in animals subjected to IMS analysis of renal lipid profiles. Treatments were the same as in Fig. 1. A: Blood glucose levels. Correlation between tubular basement membrane (TBM) (B) or GBM (C) thickness and albuminuria: nondiabetic control (filled triangles), diabetic (filled circles), and diabetic treated with PM (filled squares). Linear regression lines were calculated using Sigma Plot software. Expansion of renal mesangial matrix (D) and renal sclerosis/fibrosis (E) were scored on a scale of 0 to 3 as described under Methods (see supplementary Figs. I, II for supporting data). Sclerosis/fibrosis score is an average of the scores for global sclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and vascular fibrosis. F: Glomerular deposition of fibronectin determined by MALDI MS (see supplementary Figs. IV, V for supporting data). Each bar graph represents the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, diabetic versus nondiabetic groups; **P < 0.05, diabetic versus diabetic + PM groups; n = 3.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for unpaired samples or ANOVA followed by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls comparisons. For the MALDI imaging datasets, the mean and standard error were calculated for each MS peak of interest. Differences were evaluated by the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test followed by post hoc Tukey test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Renal pathology in the eNOS−/− C57BLKS db/db mouse model of type 2 DN

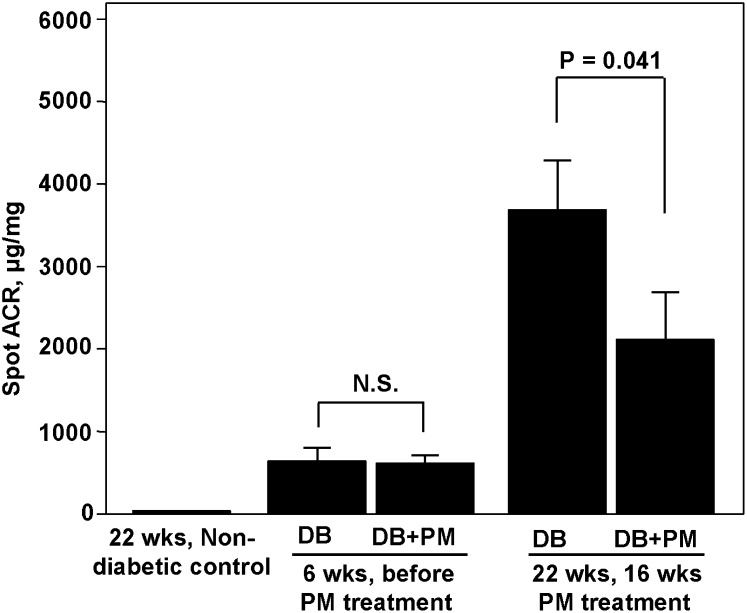

We employed eNOS−/− C57BLKS db/db mice, the most robust mouse model of type 2 DN to date. At >20 weeks of age, these mice exhibit albuminuria, arteriolar hyalinosis, increased GBM thickness, mesangial expansion, mesangiolysis, focal segmental and early nodular glomerulosclerosis, and markedly decreased glomerular filtration rate (12). In our study, eNOS−/− C57BLKS db/db mice developed significant albuminuria at 6 weeks of age, which increased dramatically by 22 weeks of age (Fig. 1). Treatment of diabetic mice with PM significantly ameliorated albuminuria at 22 weeks of age (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in diabetic mice and effect of PM treatment. Nondiabetic control C57BLKS and diabetic eNOS−/− C57BLKS db/db mice were housed as described under Methods. PM treatment of diabetic mice (400 mg/kg/day) started at 6 weeks of age and continued until 22 weeks of age. Urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) in diabetic (DB) and diabetic + PM (DB+PM) groups was determined before and at the end of PM treatment; urinary ACR in the nondiabetic control group was determined at 22 weeks of age. Each bar graph represents the mean ± SEM (n = 8). N.S., not significant.

Kidneys of three animals from each treatment group were taken for MALDI IMS analyses of lipids. The second set of kidneys from the same three animals in each treatment group was subjected to renal pathology analyses to allow for direct comparison of renal injury and lipid profiles. Diabetic mice exhibited a dramatic increase in glomerular and tubular pathologic lesions (Fig. 2B–F). PM treatment significantly ameliorated these lesions (Fig. 2B–F). Interestingly, PM treatment did not inhibit hyperglycemia itself (Fig. 2A). Therefore, use of PM treatment allowed us to compare renal lipid profiles in hyperglycemic animals with significantly different degrees of renal pathology.

Composition of mouse renal glomerular and tubular phospho- and glycolipids

MALDI IMS was performed on renal sections from three biological replicates in each experimental group (nondiabetic, diabetic, and diabetic + PM). Because DN lesions affect primarily glomeruli and tubules, we focused on the lipid molecular patterns localized specifically within glomerular and tubular areas of the renal cortex. We examined 60–70 glomeruli and/or tubules per mouse in each experimental group. Multiple species that belong to different lipid classes were identified within glomerular and tubular structures (supplementary Table I).

We then focused only on those specific phospho- and glycolipid species that exhibited significant changes in glomerular and/or tubular levels in diabetes compared with control. These species belonged to four lipid classes: gangliosides, sulfoglycosphingolipids, lysophospholipids, and PEs, and are highlighted in supplementary Table I.

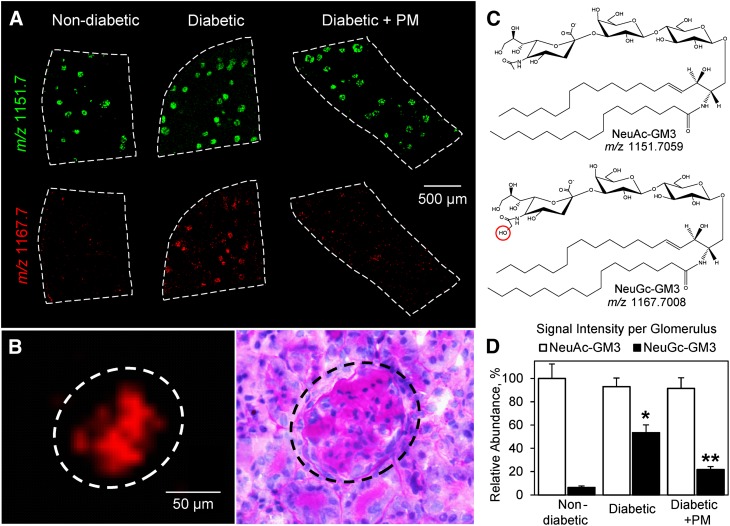

Glomerular levels of major ganglioside NeuGc-GM3 are increased in DN

Gangliosides are anionic glycosphingolipids located to the outer leaflet of plasma membranes and characterized by the presence of sialic acid in their structure (29). Gangliosides are known to play major roles in cell-cell and cell-matrix recognition via interactions with integrins, matrix proteins, and other glycosphingolipids, as well as in innate immunity, apoptosis, and carcinogenesis (30–32). We determined renal localization and levels of two abundant mammalian gangliosides, N-acetylneuraminic acid (NeuAc)-monosialodihexosylganglioside (GM3) (m/z 1,151.7) and its hydroxylated derivative N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NeuGc)-GM3 (m/z 1,167.7) (Fig. 3). Both ganglioside species were localized exclusively to renal glomeruli (Fig. 3A, B). However, there was a distinct difference in the response of these species to our experimental treatments. NeuAc-GM3 was detected at relatively high levels that were not significantly different in all treatment groups (Fig. 3A, top row; Fig. 3D). In contrast, NeuGc-GM3 was present at relatively low levels in the glomeruli of nondiabetic animals but increased ∼8-fold in the glomeruli of diabetic mice (Fig. 3A, bottom row; Fig. 3D). Diabetic mice treated with PM had significantly lower levels of NeuGc-GM3 compared with untreated diabetic mice (Fig. 3A, bottom row; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Gangliosides NeuAc-GM3 and NeuGc-GM3 show distinct changes in diabetic glomeruli. A: MALDI TOF IMS ion images of m/z 1,151.7 (NeuAc-GM3) and m/z 1,167.7 (NeuGc-GM3) in kidneys from nondiabetic control mice, diabetic mice, and diabetic mice treated with PM. MALDI IMS was performed at 10 μm spatial resolution and compared with PAS staining of the same section to confirm localization to glomeruli. B: IMS of the signal at m/z 1,167.7 and corresponding PAS staining showing the specific localization of NeuGc-GM3 to glomerulus. C: Structures of gangliosides corresponding to the signals at m/z 1,151.7 and m/z 1,167.7 as identified using FTICR MS. The bar graph (D) represents mean ± SEM for three biological replicates per group analyzing 200 glomeruli total. The average signal per glomerulus was determined in ImageJ and data were normalized to nondiabetic NeuAc-GM3. *P < 0.05, diabetic versus nondiabetic groups; **P < 0.05, diabetic versus diabetic + PM groups.

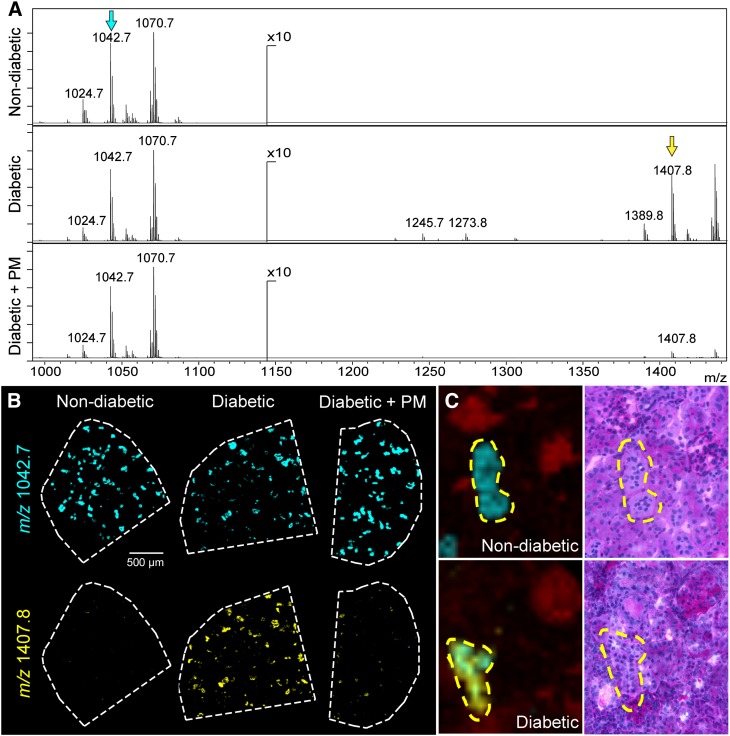

Levels of long-chain series sulfoglycolipids are increased within renal tubules in DN

Sulfoglycolipids are produced from glycosphingolipids via addition of one or several sulfate esters catalyzed by the enzyme cerebroside sulfotransferase. Sulfoglycolipids are essential in such key biological processes as nerve fiber myelination and spermatogenesis (33). They are also enriched in mammalian kidneys, where they have been shown to be involved in osmoregulation and acid-base homeostasis (34, 35). We have identified several species of sulfoglycolipids localized specifically to mouse renal tubules: sulfogalactoceramide (SM4s), sulfolactoceramide (SM3), gangliotriosylceramide sulfate (SM2a), and gangliotetraosylceramide-bis-sulfate (SB1a) and their different acyl chain derivatives (supplementary Table I; supplementary Fig. VI). There was a significant increase in the levels of sulfoglycolipid species SB1a in diabetic kidneys from 22 week old eNOS−/− db/db mice compared with controls (Fig. 4A, B). This increase was ameliorated in diabetic mice treated with PM (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast to SB1a, levels of SM3, a less polar species that possesses a relatively short sugar chain, remained unchanged in the DN model (22 week old eNOS−/− db/db mice) compared with control (Fig. 4A, B). Tubular localization of both sulfoglycolipids was confirmed by comparing the 10 μm spatial resolution IMS data to a PAS stained image of the same section (Fig. 4C). Similarly, the level of SM4s, another sulfoglycolipid with a short sugar chain, was also unchanged in diabetic tubules compared with controls (data not shown). Interestingly, SM3 and SM4s had very distinct nonoverlapping tubular localization patterns (supplementary Fig. VII).

Fig. 4.

Levels of long-chain series sulfoglycolipids are increased within diabetic renal tubules. A: Spectral region containing sulfoglycosphingolipids from tubular regions of nondiabetic, diabetic, and diabetic + PM kidneys. B: Sulfoglycolipid SM3 (t18:0/22:0), m/z 1,042.7 (cyan), was common to the renal tubules and has similar levels in all the treatment groups. Sulfoglycolipid SB1a (t18:0/22:0), m/z 1,407.8 (yellow), was increased in the tubules of the diabetic kidney and reduced upon PM treatment. These ion signals are marked with an arrow of corresponding color in (A). C: IMS overlay of the m/z 1,042.7 (cyan) and m/z 1,407.8 (yellow) ion signals displayed in (B). An ion in red specifically localized to the glomeruli is shown for reference (left panels) and the corresponding PAS stained sections are shown in the right panels. Imaging performed using MALDI TOF MS at 10 μm spatial resolution.

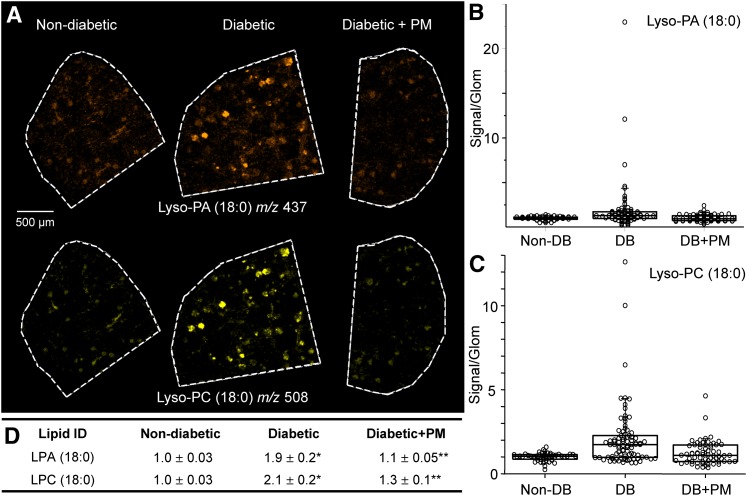

Major bioactive lysophospholipids are elevated in renal glomeruli in DN

Bioactive lysophospholipids are important signaling and regulatory molecules involved in multiple pathogenic pathways including inflammation and fibrosis, key features of kidney disease (36, 37). However, renal lysophospholipid levels in DN have not been reported. We have detected lysophospholipid species comprising two major classes, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), in the mouse renal glomeruli (supplementary Table I). The levels of both lysophospholipid classes were significantly increased in glomeruli of diabetic mice (Fig. 5). Moreover, LPC levels were most prominently increased within those individual glomeruli exhibiting higher levels of fibrosis as determined by PAS staining (supplementary Fig. VIII). Levels were significantly diminished in diabetic mice treated with PM (Fig. 5B–D). Other lysophospholipid classes, such as lysophosphatidylserine, lysophosphatidylglycerol, and lysophosphatidylethanolamine, were not detected in our study, possibly due to the sensitivity limits, as their reported physiological levels in mouse plasma are two to three orders of magnitude lower compared with major lysophospholipids (37).

Fig. 5.

Levels of LPA and LPC increase in the glomeruli of diabetic kidneys. A: MALDI TOF IMS images showing glomerular localization and levels for representative LPA and LPC species (LPA 18:0) and (LPC 18:0). Distribution of LPA (B) and LPC (C) levels within individual glomeruli and summary statistical analyses (D). Data are normalized to nondiabetic lysophospholipid signal intensity. Each circle in the box plots represents the averaged intensity measurement from a single glomerulus as determined in ImageJ. *P < 0.05, diabetic versus nondiabetic groups; **P < 0.05, diabetic versus diabetic + PM groups.

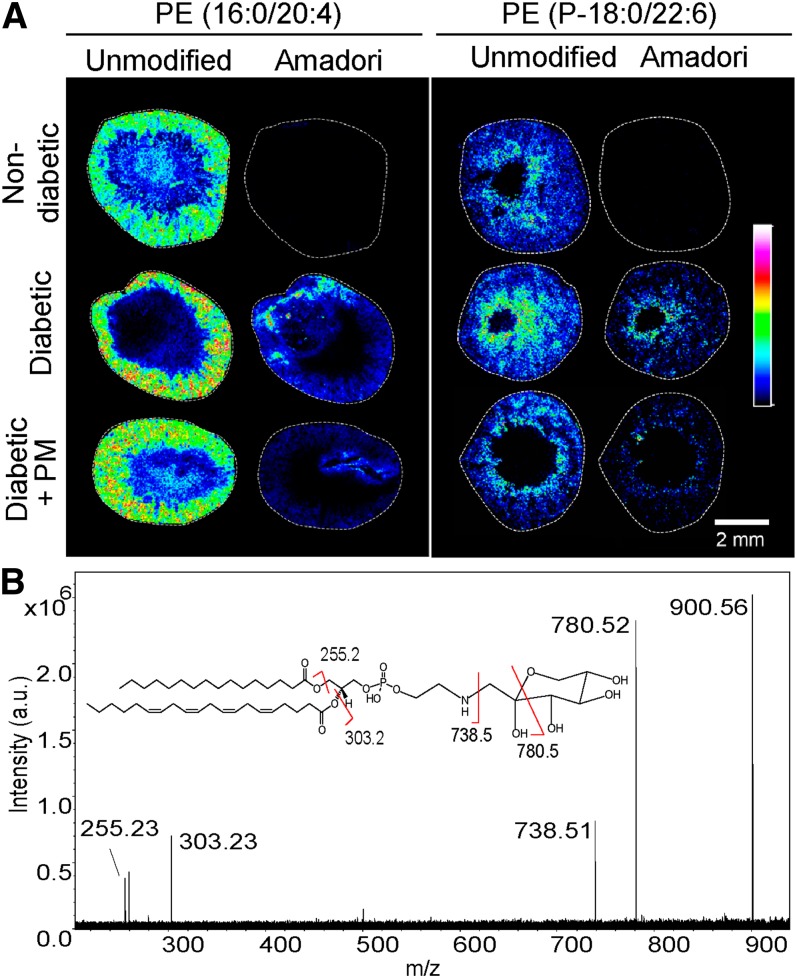

Nonenzymatic modification of PE by glucose is increased in the cortex of the DN kidney

Nonenzymatic adduction of glucose to aminophospholipids has been shown to increase in diabetic human plasma and animal tissues including kidney (38, 39). However, with the exception of diabetic atherosclerotic lesions (40), the role of glycated lipids in diabetic complications has not been investigated.

We utilized MALDI IMS to analyze glycation of different PE species in the kidney of a mouse model of DN. The identities of PE species and their glucose modification (Amadori adduct) were determined in renal tissue sections using characteristic fragmentation patterns generated by MS/MS (Fig. 6). Unmodified PE species as well as unmodified plasmalogen PE species, characterized by the presence of a vinyl ether bond at the sn-1 position (41), did not significantly change in diabetes compared with controls (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of glucose-modified (Amadori) PE species in nondiabetic, diabetic, and diabetic + PM mouse kidneys. A: FTICR IMS at 40 μm of transverse kidney sections showing localization and relative abundance of two different PE lipids along with their corresponding Amadori species. These glucose-modified species were detected in the cortex of the diabetic kidneys but not in nondiabetic kidneys. The colors represent relative signal intensity according to the scale bar on the right. B: Identification of lipid species using Amadori-PE (16:0/20:4) as an example. The FTICR MS/MS spectrum with Amadori-PE (16:0/20:4) molecular ion (m/z 900.56), product ions, and product ion assignments (inset) are shown.

Several Amadori-PE species, containing glucose adducted to the lipid amino group, were identified in the diabetic kidneys, but were not detected in the nondiabetic kidneys (supplementary Tables I, II; Fig. 6A). MALDI IMS of transverse sections through the kidney showed that these signals were present in the cortex of the kidney. Treatment of diabetic mice with PM, did not significantly affect Amadori-PE levels (Fig. 6; supplementary Table II), however, a tendency toward lower levels was observed in renal specimens from PM-treated mice (supplementary Table II).

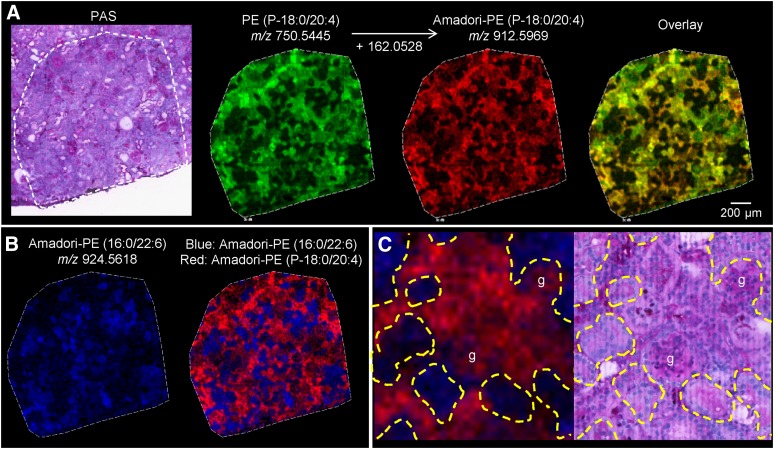

To determine more precise localization patterns of Amadori-PE species within the renal cortex, a region of the cortex in the diabetic kidney was imaged at high spatial resolution with a 10 μm step size (Fig. 7). First, we found that PE lipids were not uniformly distributed throughout the cortex, but had uniquely localized patterns. Next, we established that the unmodified and the Amadori forms of the same lipid species colocalize to the same areas of the cortex. This can be seen in Fig. 7A where PE (P-18:0/20:4) and Amadori-PE (P-18:0/20:4) show the same localization pattern. Additionally, we determined that the majority of Amadori-PE species follow two major localization patterns in the renal cortex exemplified by the complementary patterns of Amadori-PE (16:0/22:6) and plasmalogen Amadori-PE (P-18:0/20:4) (Fig. 7B). The former is localized exclusively to a distinct set of tubules, while the latter has a mixed glomerular and tubular localization (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

High spatial resolution (10 μm) MALDI FTICR IMS of glycated PEs. A: Unmodified PEs and corresponding Amadori-PEs are colocalized to the same areas of the cortex. As an example, an overlay of PE (P-18:0/20:4) (green) and Amadori-PE (P-18:0/20:4) (red) shows colocalization in yellow. B: Two distinct spatial localization patterns of glycated PE species in the renal cortex. Amadori-PE (16:0/22:6) (blue) displays the opposite localization pattern to Amadori-PE (P-18:0/20:4) [red, shown as a single ion image in (A)]. C: Zoom in on the IMS overlay from (B) (left) and corresponding region of the same section after staining with PAS (right). Amadori-PE (P-18:0/20:4) (red) is localized to glomeruli and some tubules while Amadori-PE (16:0/22:6) (blue) is localized to a distinct set of tubules. g, glomerulus.

DISCUSSION

Progress in science and medicine is closely associated with development of new experimental technologies that allow investigations to answer previously intractable questions concerning biological differences in normal and diseased tissue. The recent development of MALDI IMS technology enables molecular profiling of specific areas of the tissues while preserving tissue morphology. This technology has been instrumental in understanding molecular changes on the border between normal and cancer tissues (42), classifying tumor types (28, 43), determining tissue drug distributions (44, 45), and identifying candidate markers of disease (20, 46). As demonstrated in this study, it is now possible to analyze the molecular composition and molecular modifications in distinct renal tissue regions, and even within smaller structures such as glomeruli and tubules. With the expected further improvement of spatial resolution (<1 μm), specific structural features within the glomerulus such as mesangium, GBM, and even individual glomerular cells could be targeted for analysis.

As with any methodology, IMS also has limitations. With MALDI IMS there are no upstream separation steps which could help increase the depth of coverage and sensitivity. MALDI IMS involves the addition of a chemical matrix to the tissue section. Molecules must be extracted from the tissue and matrix layer and be ionized to be detected. Because certain matrices favor certain classes of molecules, careful matrix choice or use of different matrices in parallel analyses is critical to enhance detection of analytes of interest. These current limitations of MALDI IMS are tradeoffs for minimal tissue processing and the molecular localization information.

Here, we utilized MALDI IMS technology to determine DN-related changes of molecular species from four major lipid classes in the renal cortex, including individual glomeruli and tubules, determined directly from thin kidney sections. We employed a mouse model of DN known to exhibit severe renal damage (47), which was also observed in our study (Figs. 1, 2). Additionally, PM treatment was utilized in one experimental group which showed a reduction in albuminuria (Fig. 1). This is consistent with the observed protective effects of PM on renal function demonstrated in several diabetic animal models (14, 22, 48, 49) and in clinical trials, particularly at the early stages of the disease (50, 51).

Previous studies reported changes in ganglioside levels and metabolism in diabetic animal models (52–54). However, this is the first report on specific glomerular localization and levels of major gangliosides in DN. Of particular interest is the observed dramatic increase in the levels of NeuGc-GM3 in diabetic glomeruli (Fig. 3). As sialic acids are synthesized via a branch of the glycolytic pathway, the increased flux through this pathway in diabetes may contribute to such increase. However, because sialic acid NeuAc is a precursor of NeuGc and ganglioside NeuAc-GM3 did not increase in diabetes (Fig. 3A, top row), this mechanism is unlikely. Alternatively, NeuGc-GM3 may derive via nonenzymatic hydroxylation of the acetyl moiety of NeuAc-GM3 by hydroxyl radicals produced in diabetic oxidative stress (55, 56). This mechanism is consistent with decreased NeuGc-GM3 levels in the glomeruli of diabetic mice treated with PM, which has been shown to scavenge hydroxyl radical under high glucose conditions (16, 57). Interestingly, unlike in all other mammals, ganglioside NeuGc-GM3 is not metabolically produced in humans and is present only at trace levels in normal human tissues, most likely due to dietary sources (58). However, NeuGc-GM3 is significantly increased in many human tumors where it may act as xeno-autoantigen causing chronic inflammation (58). Therefore, it is possible that diabetic oxidative stress facilitates oxidation of NeuAc-GM3 and accumulation of NeuGc-GM3 in glomeruli, thus contributing to chronic inflammation in DN.

Our results suggest that sulfoglycolipids may play a role in DN pathogenesis. The exact mechanism remains to be elucidated. However, it is interesting that isolated rat renal tubules exposed to exogenous glucose in vitro showed increases in the levels of SM2a and SB1a but not SM3 sulfoglycolipids (59), similar to our results in DN mouse model (Fig. 4). Experiments using cerebroside sulfotransferase knockout mice, which do not synthesize sulfoglycolipids, have demonstrated significant reduction in monocyte infiltration of renal interstitium after ureteral obstruction in the knockout compared with the wild-type mice. These studies suggested that sulfoglycolipids may promote renal inflammation and tubulointerstitial injury, possibly via ligation of L-selectin (60).

It is well-established that lysophospholipids are important signaling and regulatory molecules involved in multiple pathogenic pathways (36, 37). Lysophospholipid species may regulate cell signaling through altering the structure and fluidity of a lipid bilayer, particularly above their critical micelle concentration (37). In this regard, the significant increase in glomerular lysophospholipid demonstrated in our study may facilitate critical micelle concentration transition, thus affecting activities of membrane proteins (61, 62). However, most of the biological effects of lysophospholipids are mediated via G-protein-coupled receptors. Particularly interesting is pro-fibrotic activity of LPA mediated via LPA1 receptor as has been demonstrated in UUO mouse model of renal fibrosis (63). More recently, the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) has been shown to mediate pro-inflammatory action of LPA (64). Because expression of RAGE is upregulated in diabetic kidney (65), LPA-RAGE interaction may contribute to inflammatory damage in DN. Involvement of LPC in renal pathology is indirectly suggested by the elevated LPC levels in plasma of patients with renal disease (66, 67). In the in vitro studies, LPC induced proliferation of cultured mesangial cells via a mechanism involving activation of EGF receptor signaling (68). It is yet unknown whether engagement of this receptor with LPC is involved in pathogenesis of renal disease.

While prior studies have shown the elevated levels of Amadori-PEs in plasma of diabetic patients and in different organs of diabetic animal models (38, 39), ours is the first report establishing a relationship between glycated PEs and DN. Glycated PEs have been shown to alter the structure and stability of cell membrane proteins and promote lipid peroxidation (40, 69), thus exhibiting pathogenic potential. Our results suggest that Amadori-PEs play a minor role in DN pathogenesis. The levels of different Amadori-PE species in renal cortex were significantly elevated in diabetes but were not significantly inhibited upon PM treatment, even though a tendency toward lower levels was observed (supplementary Table II). The notion that nonoxidative glucose adduction to PE has low pathogenicity is consistent with the previous findings using mice deficient in fructosamine-3-kinase, the enzyme that facilitates dissociation of Amadori adducts to amino groups. These mice did not exhibit a pathogenic phenotype in any organs, including kidney, despite having significantly elevated levels of Amadori-modified tissue proteins (70).

In summary, our data demonstrate that the levels of specific phospho- and glycolipids in glomeruli and/or tubules of the kidney are associated with diabetic renal pathology. These lipid changes were detected in tubules and glomeruli, major sites of DN lesions. Through the use of PM, we also demonstrated that the inhibition of nonenzymatic oxidative pathways ameliorated lipid levels and renal pathology, suggesting that hyperglycemia-induced oxidative pathways are required for the observed changes of lipid profiles in DN. The propensity to these oxidative pathways may contribute to individual susceptibility to DN in diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- DN

- diabetic nephropathy

- FTICR

- Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- GBM

- glomerular basement membrane

- GM3

- monosialodihexosylganglioside

- IMS

- imaging MS

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- NeuAc

- N-acetylneuraminic acid

- NeuGc

- N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- PAS

- periodic acid-Schiff

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PM

- pyridoxamine

- RAGE

- receptor for advanced glycation end products

- SB1a

- gangliotetraosylceramide-bis-sulfate

- SM2a

- gangliotriosylceramide sulfate

- SM3

- sulfolactoceramide

- SM4s

- sulfogalactoceramide

This work was supported, in part, by the research grants from the National Institutes of Health 5P41 GM103391-03 (R.M.C.) [formerly 5P41RR031461-02 (R.M.C.)], DK065138 (B.G.H.), and from the Vanderbilt O’Brien Center DK79341 (R.C.H.). B.G.H. owns stock of NephroGenex, a company that develops pyridoxamine for treatment of diabetic nephropathy.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of eight figures and two tables.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins A. J., Foley R. N., Chavers B., Gilbertson D., Herzog C., Johansen K., Kasiske B., Kutner N., Liu J., St. Peter W., et al. 2012. United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease & end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 59(1 Suppl 1): e1–e420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutledge J. C., Ng K. F., Aung H. H., Wilson D. W. 2010. Role of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6: 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balla T. 2013. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93: 1019–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinnunen P. K., Kaarniranta K., Mahalka A. K. 2012. Protein-oxidized phospholipid interactions in cellular signaling for cell death: from biophysics to clinical correlations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1818: 2446–2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weijers R. N. 2012. Lipid composition of cell membranes and its relevance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 8: 390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galadari S., Rahman A., Pallichankandy S., Galadari A., Thayyullathil F. 2013. Role of ceramide in diabetes mellitus: evidence and mechanisms. Lipids Health Dis. 12: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo S. B., Ross J. S., Cowart L. A. 2013. Sphingolipids in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic disease. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2013: 373–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramanadham S., Hsu F-F., Zhang S., Bohrer A., Ma Z., Turk J. 2000. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analysis of INS-1 insulinoma cell phospholipids. Comparison to pancreatic islets and effects of fatty acid supplementation on phospholipid composition and insulin secretion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1484: 251–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu F. F., Bohrer A., Wohltmann M., Ramanadham S., Ma Z. M., Yarasheski K., Turk J. 2000. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analyses of changes in tissue phospholipid molecular species during the evolution of hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Lipids. 35: 839–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprioli R. M., Farmer T. B., Gile J. 1997. Molecular imaging of biological samples: localization of peptides and proteins using MALDI-TOF MS. Anal. Chem. 69: 4751–4760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaurand P., Norris J. L., Cornett D. S., Mobley J. A., Caprioli R. M. 2006. New developments in profiling and imaging of proteins from tissue sections by MALDI mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 5: 2889–2900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao H. J., Wang S., Cheng H., Zhang M. Z., Takahashi T., Fogo A. B., Breyer M. D., Harris R. C. 2006. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17: 2664–2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voziyan P. A., Hudson B. G. 2005. Pyridoxamine as a multifunctional pharmaceutical: targeting pathogenic glycation and oxidative damage. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62: 1671–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degenhardt T. P., Alderson N. L., Arrington D. D., Beattie R. J., Basgen J. M., Steffes M. W., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. 2002. Pyridoxamine inhibits early renal disease and dyslipidemia in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Kidney Int. 61: 939–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voziyan P., Brown K. L., Chetyrkin S., Hudson B. 2014. Site-specific AGE modifications in the extracellular matrix: a role for glyoxal in protein damage in diabetes. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 52: 39–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chetyrkin S. V., Mathis M. E., Ham A. J., Hachey D. L., Hudson B. G., Voziyan P. A. 2008. Propagation of protein glycation damage involves modification of tryptophan residues via reactive oxygen species: inhibition by pyridoxamine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44: 1276–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voziyan P. A., Khalifah R. G., Thibaudeau C., Yildiz A., Jacob J., Serianni A. S., Hudson B. G. 2003. Modification of proteins in vitro by physiological levels of glucose: pyridoxamine inhibits conversion of Amadori intermediate to advanced glycation end-products through binding of redox metal ions. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 46616–46624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voziyan P. A., Metz T. O., Baynes J. W., Hudson B. G. 2002. A post-Amadori inhibitor pyridoxamine also inhibits chemical modification of proteins by scavenging carbonyl intermediates of carbohydrate and lipid degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 3397–3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsching C., Eckhardt M., Gröne H-J., Sandhoff R., Hopf C. 2011. Imaging of complex sulfatides SM3 and SB1a in mouse kidney using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 401: 53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruh H., Salonikios T., Fuchser J., Schwartz M., Sticht C., Hochheim C., Wirnitzer B., Gretz N., Hopf C. 2013. MALDI imaging MS reveals candidate lipid markers of polycystic kidney disease. J. Lipid Res. 54: 2785–2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko Y., Obata Y., Nishino T., Kakeya H., Miyazaki Y., Hayasaka T., Setou M., Furusu A., Kohno S. 2011. Imaging mass spectrometry analysis reveals an altered lipid distribution pattern in the tubular areas of hyper-IgA murine kidneys. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 91: 614–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng F., Zeng Y. J., Plati A. R., Elliot S. J., Berho M., Potier M., Striker L. J., Striker G. E. 2006. Combined AGE inhibition and ACEi decreases the progression of established diabetic nephropathy in B6 db/db mice. Kidney Int. 70: 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chetyrkin S. V., Kim D., Belmont J. M., Scheinman J. I., Hudson B. G., Voziyan P. A. 2005. Pyridoxamine lowers kidney crystals in experimental hyperoxaluria: A potential therapy for primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int. 67: 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanetsuna Y., Takahashi K., Nagata M., Gannon M. A., Breyer M. D., Harris R. C., Takahashi T. 2007. Deficiency of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase confers susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in nephropathy-resistant inbred mice. Am. J. Pathol. 170: 1473–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angel P. M., Spraggins J. M., Baldwin H. S., Caprioli R. 2012. Enhanced sensitivity for high spatial resolution lipid analysis by negative ion mode matrix assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84: 1557–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hankin J. A., Barkley R. M., Murphy R. C. 2007. Sublimation as a method of matrix application for mass spectrometric imaging. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 18: 1646–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J., Caprioli R. M. 2011. Matrix sublimation/recrystallization for imaging proteins by mass spectrometry at high spatial resolution. Anal. Chem. 83: 5728–5734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornett D. S., Mobley J. A., Dias E. C., Andersson M., Arteaga C. L., Sanders M. E., Caprioli R. M. 2006. A novel histology-directed strategy for MALDI-MS tissue profiling that improves throughput and cellular specificity in human breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 5: 1975–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Echten G., Sandhoff K. 1993. Ganglioside metabolism. Enzymology, topology, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 5341–5344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varki N. M., Varki A. 2007. Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease. Lab. Invest. 87: 851–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schauer R. 2009. Sialic acids as regulators of molecular and cellular interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19: 507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malykh Y. N., Schauer R., Shaw L. 2001. N-Glycolylneuraminic acid in human tumours. Biochimie. 83: 623–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honke K., Zhang Y., Cheng X., Kotani N., Taniguchi N. 2004. Biological roles of sulfoglycolipids and pathophysiology of their deficiency. Glycoconj. J. 21: 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niimura Y., Moue T., Takahashi N., Nagai K. 2010. Medium osmolarity-dependent biosynthesis of renal cellular sulfoglycolipids is mediated by the MAPK signaling pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1801: 1155–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stettner P., Bourgeois S., Marsching C., Traykova-Brauch M., Porubsky S., Nordstrom V., Hopf C., Kosters R., Sandhoff R., Wiegandt H., et al. 2013. Sulfatides are required for renal adaptation to chronic metabolic acidosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110: 9998–10003 [Erratum. 2013. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110: 14813.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rancoule C., Pradere J. P., Gonzalez J., Klein J., Valet P., Bascands J. L., Schanstra J. P., Saulnier-Blache J. S. 2011. Lysophosphatidic acid-1-receptor targeting agents for fibrosis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 20: 657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grzelczyk A., Gendaszewska-Darmach E. 2013. Novel bioactive glycerol-based lysophospholipids: new data–new insight into their function. Biochimie. 95: 667–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoji N., Nakagawa K., Asai A., Fujita I., Hashiura A., Nakajima Y., Oikawa S., Miyazawa T. 2010. LC-MS/MS analysis of carboxymethylated and carboxyethylated phosphatidylethanolamines in human erythrocytes and blood plasma. J. Lipid Res. 51: 2445–2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sookwong P., Nakagawa K., Fujita I., Shoji N., Miyazawa T. 2011. Amadori-glycated phosphatidylethanolamine, a potential marker for hyperglycemia, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Lipids. 46: 943–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravandi A., Kuksis A., Shaikh N. A. 2000. Glucosylated glycerophosphoethanolamines are the major LDL glycation products and increase LDL susceptibility to oxidation: evidence of their presence in atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20: 467–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorgas K., Teigler A., Komljenovic D., Just W. W. 2006. The ether lipid-deficient mouse: tracking down plasmalogen functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1763: 1511–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oppenheimer S. R., Mi D., Sanders M. E., Caprioli R. M. 2010. Molecular analysis of tumor margins by MALDI mass spectrometry in renal carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 9: 2182–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazova R., Seeley E. H., Keenan M., Gueorguieva R., Caprioli R. M. 2012. Imaging mass spectrometry—a new and promising method to differentiate Spitz nevi from Spitzoid malignant melanomas. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 34: 82–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khatib-Shahidi S., Andersson M., Herman J. L., Gillespie T. A., Caprioli R. M. 2006. Direct molecular analysis of whole-body animal tissue sections by imaging MALDI mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 78: 6448–6456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Römpp A., Guenther S., Takats Z., Spengler B. 2011. Mass spectrometry imaging with high resolution in mass and space (HR2 MSI) for reliable investigation of drug compound distributions on the cellular level. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 401: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meistermann H., Norris J. L., Aerni H-R., Cornett D. S., Friedlein A., Erskine A. R., Augustin A. l., De Vera Mudry M. C., Ruepp S., Suter L., et al. 2006. Biomarker discovery by imaging mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 5: 1876–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M-Z., Wang S., Yang S., Yang H., Fan X., Takahashi T., Harris R. C. 2012. Role of blood pressure and the renin-angiotensin system in development of diabetic nephropathy (DN) in eNOS-/- db/db mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 302: F433–F438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanimoto M., Gohda T., Kaneko S., Hagiwara S., Murakoshi M., Aoki T., Yamada K., Ito T., Matsumoto M., Horikoshi S., et al. 2007. Effect of pyridoxamine (K-163), an inhibitor of advanced glycation end products, on type 2 diabetic nephropathy in KK-A(y)/Ta mice. Metabolism. 56: 160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugimoto H., Grahovac G., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. 2007. Renal fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis in a new mouse model of diabetic nephropathy and its regression by bone morphogenic protein-7 and advanced glycation end product inhibitors. Diabetes. 56: 1825–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams M. E., Bolton W. K., Khalifah R. G., Degenhardt T. P., Schotzinger R. J., McGill J. B. 2007. Effects of pyridoxamine in combined phase 2 studies of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy. Am. J. Nephrol. 27: 605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis E. J., Greene T., Spitalewiz S., Blumenthal S., Berl T., Hunsicker L. G., Pohl M. A., Rohde R. D., Raz I., Yerushalmy Y., et al. 2012. Pyridorin in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23: 131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masson E., Troncy L., Ruggiero D., Wiernsperger N., Lagarde M., El Bawab S. 2005. a-Series gangliosides mediate the effects of advanced glycation end products on pericyte and mesangial cell proliferation: a common mediator for retinal and renal microangiopathy? Diabetes. 54: 220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zador I. Z., Deshmukh G. D., Kunkel R., Johnson K., Radin N. S., Shayman J. A. 1993. A role for glycosphingolipid accumulation in the renal hypertrophy of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 91: 797–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu G., Han F., Yang Y., Xie Y., Jiang H., Mao Y., Wang H., Wang M., Chen R., Yang J., et al. 2011. Evaluation of sphingolipid metabolism in renal cortex of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes and the effects of rapamycin. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 26: 1493–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mwangi D. W., Bansal D. D. 2004. Evidence of free radical participation in N-glycolylneuraminic acid generation in liver of chicken treated with gallotannic acid. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 41: 20–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan Y., Lim Y. B., Altieri K. E., Seitzinger S. P., Turpin B. J. 2012. Mechanisms leading to oligomers and SOA through aqueous photooxidation: insights from OH radical oxidation of acetic acid and methylglyoxal. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12: 801–813 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chetyrkin S., Mathis M., Hayes McDonald W., Shackelford X., Hudson B., Voziyan P. 2011. Pyridoxamine protects protein backbone from oxidative fragmentation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411: 574–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Padler-Karavani V., Yu H., Cao H., Chokhawala H., Karp F., Varki N., Chen X., Varki A. 2008. Diversity in specificity, abundance, and composition of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in normal humans: potential implications for disease. Glycobiology. 18: 818–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagai K., Tadano-Aritomi K., Niimura Y., Ishizuka I. 2008. Effect of nutritional substrate on sulfolipids metabolic turnover in isolated renal tubules from rat. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. 84: 24–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogawa D., Shikata K., Honke K., Sato S., Matsuda M., Nagase R., Tone A., Okada S., Usui H., Wada J., et al. 2004. Cerebroside sulfotransferase deficiency ameliorates L-selectin-dependent monocyte infiltration in the kidney after ureteral obstruction. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 2085–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lundbaek J. A., Andersen O. S. 1994. Lysophospholipids modulate channel function by altering the mechanical properties of lipid bilayers. J. Gen. Physiol. 104: 645–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ben-Zeev G., Telias M., Nussinovitch I. 2010. Lysophospholipids modulate voltage-gated calcium channel currents in pituitary cells; effects of lipid stress. Cell Calcium. 47: 514–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pradère J. P., Gonzalez J., Klein J., Valet P., Grès S., Salant D., Bascands J. L., Saulnier-Blache J. S., Schanstra J. P. 2008. Lysophosphatidic acid and renal fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1781: 582–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rai V., Toure F., Chitayat S., Pei R., Song F., Li Q., Zhang J., Rosario R., Ramasamy R., Chazin W. J., et al. 2012. Lysophosphatidic acid targets vascular and oncogenic pathways via RAGE signaling. J. Exp. Med. 209: 2339–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanji N., Markowitz G. S., Fu C., Kislinger T., Taguchi A., Pischetsrieder M., Stern D., Schmidt A. M., D’Agati V. D. 2000. Expression of advanced glycation end products and their cellular receptor RAGE in diabetic nephropathy and nondiabetic renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11: 1656–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sasagawa T., Suzuki K., Shiota T., Kondo T., Okita M. 1998. The significance of plasma lysophospholipids in patients with renal failure on hemodialysis. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo). 44: 809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pang L. Q., Liang Q. L., Wang Y. M., Ping L., Luo G. A. 2008. Simultaneous determination and quantification of seven major phospholipid classes in human blood using normal-phase liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray mass spectrometry and the application in diabetes nephropathy. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 869: 118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bassa B. V., Noh J. W., Ganji S. H., Shin M. K., Roh D. D., Kamanna V. S. 2007. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates EGF receptor activation and mesangial cell proliferation: regulatory role of Src and PKC. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1771: 1364–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levi V., Villamil Giraldo A. M., Castello P. R., Rossi J. P., Gonzalez Flecha F. L. 2008. Effects of phosphatidylethanolamine glycation on lipid-protein interactions and membrane protein thermal stability. Biochem. J. 416: 145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Veiga da-Cunha M., Jacquemin P., Delpierre G., Godfraind C., Theate I., Vertommen D., Clotman F., Lemaigre F., Devuyst O., Van Schaftingen E. 2006. Increased protein glycation in fructosamine 3-kinase-deficient mice. Biochem. J. 399: 257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.