Our population-based study established epidemiological baseline data for symptomatic degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis in adults in Beijing, China, especially for people younger than 40 years. Our findings indicate that lumbar osteoarthritis is an epidemic in Beijing and will become a more severe problem as society ages.

Keywords: prevalence, feature, lumbar osteoarthritis, degenerative disease, population-based, cross-sectional study

Abstract

Study Design.

A population-based study.

Objective.

To study the prevalence and features of symptomatic degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis in adults.

Summary of Background Data.

Lumbar osteoarthritis adversely affects individuals and is a heavy burden. There are limited data on the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis.

Methods.

A representative, multistage sample of adults was collected. Symptomatic degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis was diagnosed by clinical symptoms, physical examinations, and imaging examinations. Personal information was obtained by face-to-face interview. Information included the place of residence, age, sex, income, type of medical insurance, education level, body mass index, habits of smoking and drinking, type of work, working posture, duration of the same working posture during the day, mode of transportation, exposure to vibration, and daily amount of sleep. Crude and adjusted prevalence was calculated. The features of populations were analyzed by multivariable logistic regression in total and subgroup populations.

Results.

The study included 3859 adults. The crude and adjusted prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis was 9.02% and 8.90%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis between urban, suburban, and rural populations (7.66%, 9.97%, and 9.44%) (P = 0.100). The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis was higher in females (10.05%) than in males (9.1%, P = 0.021). The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis increased with increasing age. Obese people (body mass index >28 kg/m2), those engaged in physical work, those who maintained the same work posture for 1 to 1.9 hours per day, those who were exposed to vibration during daily work, and those who got less than 7 hours of sleep per day had a higher prevalence. These features differed by subgroup.

Conclusion.

This study established epidemiological baseline data for degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis in adults, especially for people younger than 45 years. Lumbar osteoarthritis is epidemic in Beijing and will become a more severe problem in aging society. Different populations have different features that require targeted interventions.

Level of Evidence: 2

Lumbar osteoarthritis encompasses a series of diseases caused by lumbar degeneration. Although lumbar osteoarthritis is not a major cause of death in China, the back pain associated with lumbar osteoarthritis often causes disability and loss of work days. Therefore, this condition represents a heavy disease burden.1–6 Conventional lumbar osteoarthritis treatment is conservative or surgical. Surgical treatment includes a high recurrence rate of lumbar disc herniation (range, 9% to 10.2%).7,8 The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis differs by country. For example, the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis in Britain is higher than that in Japan.9 In China, lumbar osteoarthritis is a common disease, with the highest prevalence in western regions.10 Moreover, lumbar degeneration becomes more severe with age.11 According to data from the Sixth National Population Census in China, Beijing has become an aging society.12 Beijing is one of the most developed cities in China, and it has undergone tremendous change during the past decade, including aging, rapid socioeconomic development, and urbanization. However, knowledge on the prevalence and distribution of lumbar osteoarthritis based on a large representative sample of Beijing residents is limited.

Lumbar osteoarthritis is caused by environmental and genetic factors.13 Previous studies have shown that, among environmental risk factors, the most commonly suspected factors for accelerating degeneration are age, occupational physical loading, back injury, and smoking status.14 In addition, some populations are at higher risk for lumbar osteoarthritis, including athletes and less active females.15,16 In China, the prevalence of lumbar disc herniation is high in civil servants (44.8%).17 To date, the factors that eventually cause pathological progression have not been determined. However, along with recent economic development, living, environmental, and working conditions have substantially changed in China. These changes may underlie the emergence of risk factors for lumbar osteoarthritis.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the current prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of lumbar osteoarthritis, and to characterize the populations at risk in a large sample of Chinese adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants

This community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in December 2010. A multistage, stratified sampling method was used to select a representative sample of persons aged 18 years or older who had lived in Beijing for at least 6 months. First, the sampling process was stratified by place of residence (urban, suburban, or rural). Two administrative districts in the 3 geographic regions were randomly sampled. Second, a community or village was randomly selected from each administrative district. Third, 2 to 3 residential buildings from each urban and suburban area, and 2 to 5 streets from each rural area, based on the number of residents, were sampled randomly. All living family members in the sampled buildings and streets were included in the study. A total of 3900 subjects were invited to participate in this study, of whom, 3888 completed the study. The overall response rate was 99.7% (99.6% for males and 99.8% for females). Among the 3888 persons interviewed, 29 did not provide adequate disease information. The final analysis included the remaining 3859 individuals.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and the ethics committee of Beijing Jishuitan Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before data were collected.

Diagnostic Criteria

Lumbar osteoarthritis was diagnosed according to routine diagnosis practice, including clinical symptoms, such as back pain and numbness, physical examinations, and imaging examinations. Imaging examinations included radiography or/and computed tomography or/and magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging examinations were mandatory for diagnosing lumbar osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis caused by injury was excluded.

Data Collection

The relevant information was obtained by face-to-face interview. The information included place of residence, age, sex, per capita monthly income, education level, type of medical insurance, education level, body mass index (BMI, measured as weight in kg2 divided by height in cm), smoking, drinking, type of work (sedentary, completely physical, or mixed), exposure to vibration, working posture, duration of the same working posture during the day, modes of transportation used (car, public transportation, bicycle, and walking), and number of hours of sleep per day. Cigarette smoking was defined as the current use of at least 1 cigarette per day for at least 1 month or having used at least 100 cigarettes during a lifetime. Alcohol use was defined as the consumption of 1000 mL of beer or 100 mL of liquor per week for 1 year or more. Exposure to vibration was defined as operating a motor or a similar working environment in which movement was felt in the body as vibration. Body weight and height were measured by the investigator with a tape measure.

A pilot study was conducted prior to the actual study to refine study parameters and test for feasibility of data collection. Investigators were trained in data collection techniques before being sent to interview participants. Data were double-entered in parallel using EpiData 3.1 (The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark).

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence was calculated as crude and adjusted rates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and categorized by place of residence (urban, suburban, rural), sex, age, income level, education, type of insurance, BMI, smoking, drinking, mode of transportation, type of work, working posture, duration of working posture, exposure to vibration, and sleep time per day. The differences were examined by χ2 tests. The characteristics of populations were analyzed by multivariable logistic regression in total and subgroup populations. Only significant variables were included in the final model. All P values were 2 tailed, were not adjusted for multiple tests, and considered significant at P < 0.05. All statistical tests were carried out using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

The study included 1820 females (47.27%) and 2029 males (52.73%). The mean age ± SD was 45.85 ± 16.19 years.

Prevalence of Lumbar Osteoarthritis

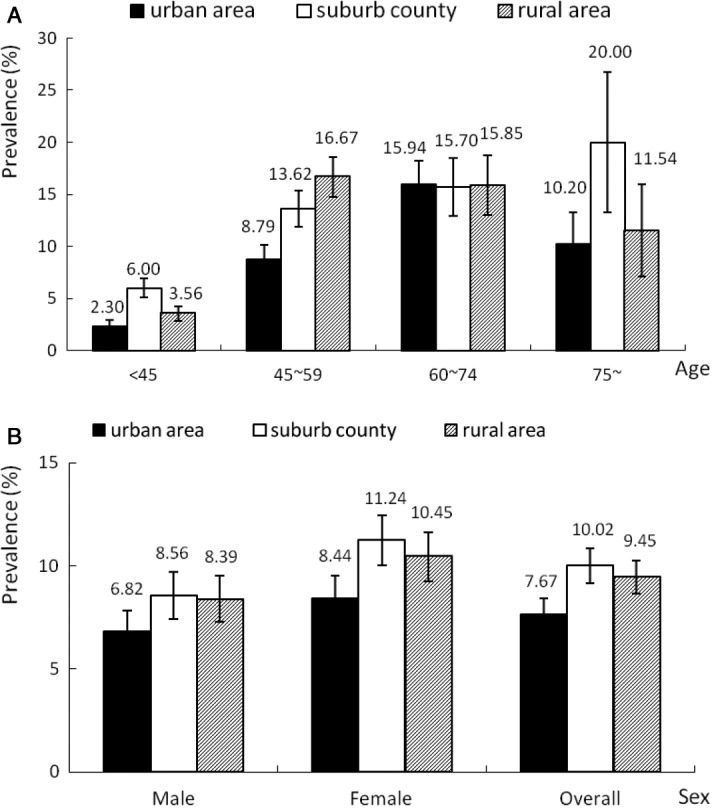

There were 348 cases of symptomatic lumbar osteoarthritis in total. And a total of 293 cases (84.20%) had back pain among them. Overall, the crude prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis was 9.02% (95% CI: 8.11%–9.92%) and the adjusted prevalence was 7.44% (95% CI: 6.21%–8.68%). The prevalence by place of residence and sex is shown in Figure 1. The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis in urban, suburban, and rural areas was 7.66%, 9.97%, and 9.44%, respectively. Differences among the regions were not significant (P = 0.100). The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis increased with increasing age in each region (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis among people living in urban, suburban, and rural areas according to sex (panel A) and age (panel B). The bars indicate prevalence ± standard error. Data on sex and age were missing for 10 subjects.

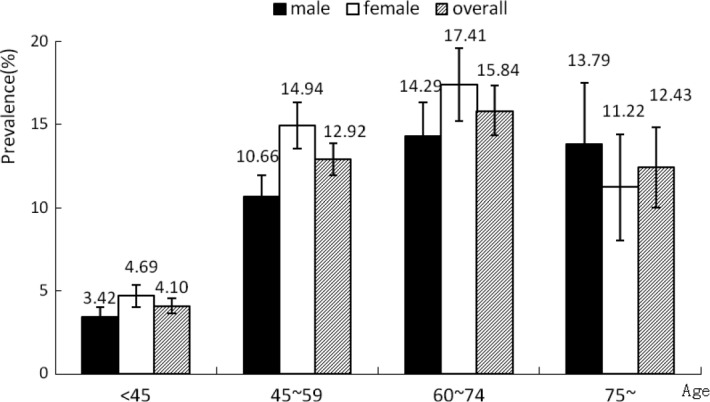

Females had a significantly higher prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis than males (10.05% vs. 7.91%, P = 0.021). This sex difference was the same in all the 3 regions (P > 0.05, Figure 1B). The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis increased with increasing age in males and females, but this prevalence was slightly decreased for those 75 years or older compared with those who were 60 to 74 years old (P < 0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sex-specific prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis by age (<45, 45–59, 60–74, and 75+ yr). The bars indicate prevalence ± standard error.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis categorized by socioeconomic status, work environment, and lifestyle variables. Persons with more education had a lower prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis (P < 0.001). Among the 4 types of insurance, persons in the new rural cooperative medical services group had the highest prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis (12.82%, P < 0.001). Persons who were engaged in physical work had the highest prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis among labor class (P < 0.001). The population with the lowest monthly income (<2000 ¥) had the highest prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis (P = 0.036).

TABLE 1. Regional and Population-Based Distribution and Characteristics of Lumbar Osteoarthritis.

| Characteristics | N | n* | P (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||

| Undergraduate or higher | 598 | 21 | 3.51 (2.04– 4.99) | <0.001 |

| Junior college | 689 | 32 | 4.64 (3.07–6.22) | |

| Senior high school | 1121 | 108 | 9.63 (7.91–11.36) | |

| Junior high school or lower | 1414 | 186 | 13.15 (11.39–14.92) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Social insurance | 2220 | 175 | 7.88 (6.76–9.00) | <0.001 |

| Medical services (state expense) | 444 | 41 | 9.23 (6.54–11.93) | |

| New rural cooperative medical services | 858 | 110 | 12.82 (10.58–15.06) | |

| Self-expense | 295 | 20 | 6.78 (3.91–9.65) | |

| Nature of work | ||||

| Physical-based | 1466 | 174 | 11.87 (10.21–13.52) | <0.001 |

| Mental-based | 919 | 63 | 6.86 (5.22–8.49) | |

| Mixed | 894 | 60 | 6.71 (5.07–8.35) | |

| Per capita monthly income level (¥) | ||||

| <2000 | 2194 | 220 | 10.03 (8.77–11.28) | 0.036 |

| 2000–4999 | 1400 | 106 | 7.57 (6.19–8.96) | |

| ≥5000 | 217 | 17 | 7.83 (4.26–11.41) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 | 235 | 7 | 2.98 (0.81–5.15) | <0.001 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1911 | 146 | 7.64 (6.45–8.83) | |

| 24.0–27.9 | 1324 | 143 | 10.80 (9.13–12.47) | |

| ≥28.0 | 366 | 50 | 13.66 (10.14–17.18) | |

| Working posture | ||||

| Sitting | 1241 | 81 | 6.53 (5.15–7.90) | <0.001 |

| Standing | 796 | 78 | 9.80 (7.73–11.86) | |

| Frequently stooping | 215 | 30 | 13.95 (9.32–18.59) | |

| Moving | 929 | 103 | 11.09 (9.07–13.11) | |

| Other | 229 | 21 | 9.17 (5.43–12.91) | |

| Duration of the same work posture (hr/d) | ||||

| <1 | 684 | 58 | 8.48 (6.39–10.57) | 0.018 |

| 1–1.9 | 819 | 98 | 11.97 (9.74–14.19) | |

| 2–2.9 | 464 | 39 | 8.41 (5.88–10.93) | |

| ≥3 | 1396 | 114 | 8.17 (6.73–9.60) | |

| Vibration | ||||

| Yes | 342 | 49 | 14.33 (10.61–18.04) | <0.001 |

| No | 3099 | 264 | 8.52 (7.54–9.50) | |

| Modes of daily transportation | ||||

| Car | 425 | 26 | 6.12 (3.84–8.40) | <0.001 |

| Public transportation | 1537 | 112 | 7.29 (5.99–8.59) | |

| Bicycle | 743 | 97 | 13.06 (10.63–15.48) | |

| On foot | 953 | 90 | 9.44 (7.59–11.30) | |

| Other | 193 | 22 | 11.40 (6.92–15.88) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 929 | 91 | 9.80 (7.88–11.71) | 0.342 |

| No | 2930 | 257 | 8.77 (7.75–9.80) | |

| Drinking | ||||

| Yes | 768 | 82 | 10.68 (8.49–12.86) | 0.073 |

| No | 3091 | 266 | 8.61 (7.62–9.59) | |

| Time spent sleeping (hr/d) | ||||

| ≥7 | 3002 | 235 | 7.83 (6.87–8.79) | <0.001 |

| <7 | 762 | 112 | 14.70 (12.18–17.21) | |

| Total | 3859 | 348 | 9.02 (8.11–9.92) | |

*Number of participants diagnosed with lumbar osteoarthritis.

P indicates prevalence; CI, confidence interval.

An increasing trend in the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis was evident with increasing BMI (P < 0.001). Persons more likely to experience lumbar osteoarthritis frequently stooped, held the same working postures for 1 to 1.9 hours per day, and were exposed to vibration during daily work (Table 1). Furthermore, people who engaged in more physical activity during daily transportation were more likely to develop lumbar osteoarthritis, except for those who used walking as their transportation. In addition, people who obtained 7 hours of sleep per day showed a remarkably lower prevalence than those who obtained less than 7 hours of sleep per day (P < 0.001).

Epidemiological Features of Lumbar Osteoarthritis

Multivariable logistic regression showed that, in the total population, females 45 years or older, obese people (BMI ≥28 kg/m2), those engaged in physical work, those holding the same work posture 1 to 1.9 hours per day, those exposed to vibration during their daily work, and those who sleep for less than 7 hours per day had a significantly increased prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Association of Various Factors With Lumbar Osteoarthritis by Multivariable Logistic Regression.

| B | SE | Wald | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||||

| Female | 0.439 | 0.141 | 9.627 | 0.002 | 1.55 | 1.18– 2.05 |

| Age (yr) | 50.830 | <0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 1.068 | 0.177 | 36.425 | <0.001 | 2.91 | 2.06–4.11 |

| 60–74 | 1.391 | 0.203 | 46.951 | <0.001 | 4.02 | 2.70–5.98 |

| ≥75 | 1.059 | 0.345 | 9.420 | 0.002 | 2.88 | 1.47–5.67 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 10.995 | 0.012 | ||||

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.00 | |||||

| <18.5 | −0.924 | 0.523 | 3.122 | 0.077 | 0.40 | 0.14–1.11 |

| 24.0–27.9 | 0.211 | 0.150 | 1.996 | 0.158 | 1.24 | 0.92–1.66 |

| ≥28.0 | 0.533 | 0.212 | 6.318 | 0.012 | 1.70 | 1.13–2.58 |

| Nature of work | 9.823 | 0.007 | ||||

| Physical | 0.374 | 0.172 | 4.720 | 0.030 | 1.45 | 1.04–2.04 |

| Mixed | −0.104 | 0.203 | 0.260 | 0.610 | 0.90 | 0.61–1.34 |

| Mental | 1.00 | |||||

| Duration of the same work posture (hr/d) | 10.934 | 0.012 | ||||

| <1 | 1.00 | |||||

| 1–1.9 | 0.550 | 0.205 | 7.210 | 0.007 | 1.73 | 1.16–2.59 |

| 2–2.9 | 0.126 | 0.246 | 0.261 | 0.609 | 1.13 | 0.70–1.84 |

| ≥3 | 0.082 | 0.204 | 0.162 | 0.687 | 1.09 | 0.73–1.62 |

| Vibration (yes) | 0.793 | 0.193 | 16.853 | <0.001 | 2.21 | 1.51–3.23 |

| Time spent sleeping <7 hr | 0.401 | 0.151 | 7.020 | 0.008 | 1.49 | 1.11–2.01 |

SE indicates standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

The characteristics of lumbar osteoarthritis differed by place of residence. Age was a common factor for all the 3 areas and the only relevant factor for urban dwellers. Exposure to vibration was important for persons living in suburban and rural areas. Sex and sleeping for less than 7 hours per day were significantly associated with lumbar osteoarthritis in suburban populations. BMI ≥28 kg/m2 and holding the same work posture for 1 to 2.9 hours per day increased the risk of lumbar osteoarthritis (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Epidemiological Characteristics of Lumbar Osteoarthritis Among 3 Regional Populations.

| Characteristics | B | SE | Wald | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban area (1) | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 36.623 | <0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 1.329 | 0.395 | 11.351 | 0.001 | 3.78 | 1.74–8.19 |

| 60–74 | 2.278 | 0.389 | 34.354 | <0.001 | 9.76 | 4.556–20.91 |

| ≥75 | 1.329 | 0.395 | 11.351 | 0.001 | 3.78 | 1.74–8.19 |

| Suburb county (4) | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||||

| Female | 0.611 | 0.253 | 5.841 | 0.016 | 1.84 | 1.12–3.02 |

| Age (yr) | 16.323 | 0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 1.058 | 0.268 | 15.605 | <0.001 | 2.88 | 1.70–4.87 |

| 60–74 | 0.874 | 0.359 | 5.936 | 0.015 | 2.40 | 1.19–4.84 |

| ≥75 | 0.898 | 0.800 | 1.259 | 0.262 | 2.46 | 0.51–11.78 |

| Vibration | 1.032 | 0.298 | 11.967 | 0.001 | 2.81 | 1.56–5.04 |

| Time spent sleeping <7 hr/d | 0.574 | 0.255 | 5.071 | 0.024 | 1.78 | 1.08–2.93 |

| Rural areas | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 37.871 | <0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 1.511 | 0.267 | 32.051 | <0.001 | 4.53 | 2.69–7.64 |

| 60–74 | 1.686 | 0.334 | 25.508 | <0.001 | 5.40 | 2.81–10.38 |

| ≥75 | 1.518 | 0.553 | 7.523 | 0.006 | 4.56 | 1.54–13.50 |

| BMI | 12.579 | 0.006 | ||||

| <18.5 | −0.876 | 0.747 | 1.375 | 0.241 | 0.42 | 0.10–1.80 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.00 | |||||

| 24.0–27.9 | 0.286 | 0.243 | 1.391 | 0.238 | 1.33 | 0.83–2.14 |

| ≥28.0 | 1.009 | 0.317 | 10.138 | 0.001 | 2.74 | 1.47–5.11 |

| Vibration | 0.802 | 0.295 | 7.406 | 0.006 | 2.23 | 1.25–3.98 |

| Duration of the same work posture (hr/d) | 13.266 | 0.004 | ||||

| <1 | 1.00 | |||||

| 1–1.9 | 1.126 | 0.367 | 9.418 | 0.002 | 3.08 | 1.50–6.33 |

| 2–2.9 | 0.975 | 0.383 | 6.496 | 0.011 | 2.65 | 1.25–5.61 |

| ≥3 | 0.446 | 0.361 | 1.520 | 0.218 | 1.56 | 0.77–3.17 |

SE indicates standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Epidemiological features of lumbar osteoarthritis were different between males and females. For both sexes, age and exposure to vibration were common features. Epidemiological features of lumbar osteoarthritis were the nature of work and getting less than 7 hours of sleep per day for males and only a BMI ≥28 kg/m2 for females (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Epidemiological Characteristics of Lumbar Osteoarthritis in Male and Female Populations.

| B | SE | Wald | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 34.272 | <0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 1.114 | 0.258 | 18.676 | <0.001 | 3.05 | 1.84–5.05 |

| 60–74 | 1.611 | 0.283 | 32.418 | <0.001 | 5.01 | 2.88–8.72 |

| ≥75 | 1.303 | 0.460 | 8.034 | 0.005 | 3.68 | 1.50–9.06 |

| Nature of work | 6.858 | 0.032 | ||||

| Physical | 1.00 | |||||

| Mixed | −0.641 | 0.254 | 6.373 | 0.012 | 0.53 | 0.32–0.87 |

| Mental | −0.393 | 0.275 | 2.044 | 0.153 | 0.68 | 0.39–1.16 |

| Vibration | 0.974 | 0.240 | 16.445 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 0.24–0.60 |

| Time spent sleeping <7 hr/d | 0.472 | 0.220 | 4.592 | 0.032 | 1.60 | 1.04–2.47 |

| Females | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 20.034 | <0.001 | ||||

| <45 | 1.00 | |||||

| 45–59 | 0.967 | 0.240 | 16.244 | <0.001 | 2.63 | 1.641–4.21 |

| 60–74 | 1.095 | 0.286 | 14.708 | <0.001 | 2.99 | 1.71–5.24 |

| ≥75 | 0.398 | 0.521 | 0.585 | 0.444 | 1.49 | 0.54–4.14 |

| BMI | 7.409 | 0.060 | ||||

| <18.5 | −0.867 | 0.610 | 2.020 | 0.155 | 0.42 | 0.13–1.39 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.00 | |||||

| 24.0–27.9 | 0.297 | 0.209 | 2.026 | 0.155 | 1.35 | 0.89–2.03 |

| ≥28.0 | 0.544 | 0.275 | 3.910 | 0.048 | 1.72 | 1.01–2.95 |

| Vibration | −0.679 | 0.339 | 4.024 | 0.045 | 0.51 | 0.26–0.99 |

BMI indicates body mass index; SE indicates standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The current prevalence data were collected from 3859 Chinese adults aged 18 years or older who had lived in Beijing for at least 6 months. We found that the overall prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis was 9.02% in a population of approximately 1.62 million patients, based on a 2010 census.12 The prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis is similar to that of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8.2%) and diabetes (9.7%),18,19 which are other severe chronic noncommunicable diseases in China. This indicates that lumbar osteoarthritis is an epidemic in the general adult population of Beijing.

The regional distribution of lumbar osteoarthritis is different among middle-aged and elderly people.20 The distribution of lumbar osteoarthritis is higher in the South and East than in the North and West (Table 5). Beijing has the lowest prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis compared with 6 other cities. Besides regional differences, the main reason for this discrepancy may be differences in disease definitions. In our study, only lumbar osteoarthritis due to lumbar degeneration was included. In general, for degeneration diseases, middle-aged and elderly people are the focus of studies. In our study, people younger than 40 years were included and had a considerable prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis. More attention to this disease needs to be paid in the young population.

TABLE 5. Prevalence of Lumbar Osteoarthritis in Different Cities in China in People Aged 40 Years or Older.

| Location in China | City in China | Males | Females | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | P | N | N | P | n | N | P | ||

| Northeast | Haerbin | 256 | 552 | 46.38 | 233 | 622 | 37.46 | 489 | 1174 | 41.65 |

| North | Shijiazhuang | 98 | 418 | 23.44 | 111 | 466 | 23.82 | 209 | 884 | 23.64 |

| East | Shanghai | 313 | 416 | 75.24 | 404 | 579 | 69.78 | 717 | 995 | 72.06 |

| South | Guangzhou | 67 | 108 | 62.04 | 123 | 194 | 63.40 | 190 | 302 | 62.91 |

| Southwest | Chengdu | 153 | 269 | 56.88 | 184 | 377 | 48.81 | 337 | 646 | 52.17 |

| West | Xi'an | 146 | 407 | 35.87 | 129 | 416 | 31.01 | 275 | 823 | 33.41 |

| North | Beijing | 121 | 1110 | 10.90 | 182 | 1212 | 15.02 | 303 | 2322 | 13.05 |

P indicates prevalence.

Consistent with the results of Li et al,20 we found that the prevalence of osteoarthritis increased with age in males and females, peaking in those aged 60 to 70 years. These characteristics indicate that lumbar osteoarthritis will become a more severe problem as the population continues to age.

Studies involving twins suggest that genetic factors are the most important risk factors for lumbar degeneration.13,21 However, as a complex and degenerative disease, the pathogenesis of lumbar osteoarthritis stems from environmental and genetic factors. In addition, according to Kanayama et al,22 degenerative lumbar discs occur in apparently healthy individuals. Using image analysis, it was found that people diagnosed as having lumbar degeneration do not always have clinical symptoms. At present, interventions that modify environmental risk factors may be the most efficient and practical means to prevent the development of lumbar osteoarthritis.

In our study, females presented as a high-risk population for lumbar osteoarthritis, which is consistent with a study by Evans et al,16 who found less active females to be at greater risk for lumbar disc degeneration. Conversely, Ong et al15 showed that Olympic athletes are more likely to experience lumbar osteoarthritis than those who were not athletes. In addition, our results suggest that getting more sleep (≥7 hr/d) is protective against lumbar osteoarthritis. According to the evidence stated in the earlier text, the degree of activity may be closely related to the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis.

In our study, obesity (BMI ≥28 kg/m2) was significantly associated with lumbar osteoarthritis. This result is consistent with Like et al,23 who showed that persistent overweight status (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) is strongly associated with an increased number of injured lumbar discs (adjusted odds ratio, 4.3; 95% CI: 1.3–14.3). Obesity has been shown to increase the risk of spinal disease.24,25 The mechanism by which obesity contributes to lumbar disc degeneration is poorly understood; it may increase the mechanical load on the spine and thereby increase the risk of degeneration and back disorders.23 In addition, obesity is thought to be an inflammatory disorder, which could be the mechanism by which it leads to intervertebral disc degeneration.26

Furthermore, this study indicates that occupational factors are important in the development of lumbar osteoarthritis. In a study by Zhang et al,27 “hardworking” was a risk factor for lumbar disc herniation, and this result was somewhat confirmed by our finding that those who were engaged in physical work had a higher risk of lumbar osteoarthritis than workers who performed a combination of physical activity and mental work In addition, we found that exposure to vibration during daily work was strongly associated with lumbar osteoarthritis. The relationship between disc degeneration and vibration is controversial. A meta-analysis showed that whole-body vibration may cause low back pain.28 Several epidemiological studies support the hypothesis that driving adversely affects intervertebral discs, and occupational drivers have a higher rate of herniation than those in other jobs.29–31 The postulated mechanism for pathogenesis in this situation is that vibration can adversely affect nutrition and metabolism of the disc, particularly if the vibration matches the resonant frequency of the lumbar spine as shown in in vivo and in vitro studies.32 However, the twin studies mentioned in the earlier text did not show an association between long-term exposure to vibration and disc degeneration.13 Our results of a large sample of Chinese adults suggest a remarkable association between lumbar osteoarthritis and whole-body vibration.

Getting less than 7 hours of sleep per day was related to lumbar osteoarthritis in this study. Too much and abnormal loading are both risk factors for lumbar muscle strain and lumbar disc degeneration.33 A shorter sleep time may mean that lumbar muscle and disc are under tension for a longer time. Therefore, this status may lead to further lumbar degeneration and be related to lumbar osteoarthritis.

In addition to the risk factors for lumbar osteoarthritis found in our cohort as a whole, risk factors differed by place of residence and sex. This result suggests that different populations have differential relevant factors that require targeted intervention.

This study has 2 limitations. First, only patients with lumbar osteoarthritis with clinical symptoms were included. Therefore, people with lumbar degeneration but without clinical symptoms were not included. This may have caused an underestimation of the prevalence of lumbar osteoarthritis. Nevertheless, it is not necessary to take measures of treatment on the underestimated people according to the current guideline. Therefore, an underestimate has little influence on policy decisions. Second, rural participants were oversampled, which may have skewed the results. However, we accounted for these issues by calculating statistical weights and reporting the adjusted prevalence.

CONCLUSION

This study established epidemiological baseline data of lumbar osteoarthritis in adults 18 years and older in Beijing for the first time, especially for people younger than 45 years. This study shows that lumbar osteoarthritis is highly endemic in Beijing adults and is set to become one of the more severe problems in the aging society. In addition, populations differ in the relevant risk factors and will therefore require targeted interventions to minimize the impact of this condition.

Key Points

The overall crude prevalence and adjusted prevalence of symptomatic degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis is 9.02% and 8.90%, respectively.

Lumbar osteoarthritis is an epidemic in Beijing and will become a more severe problem as society ages.

This study established epidemiological baseline data for degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis in adults, especially for people younger than 40 years.

Different populations have different features that require targeted interventions.

Acknowledgments

Beijing Research Institute of Traumatology and Orthopaedics provided our team with administrative support and the Second Hospital of Yanqing provided the arrangement of the sampled community. The authors thank Tang Xun, PhD, of Peking University for the advice on the design. The authors also thank Xu Xiaochuan, PhD, Zhao Danhui, MS, Wu Cheng-ai, PhD, Dr. Wang Yan, Dr. Zhang Guoying, Wang Fei, MS, and Dr. Zhang Lifeng equally, for their support on survey. Furthermore, the authors thank Wu Ting, PhD, for helping in writing. Yanwei Lv, MS, and Wei Tian, PhD, are both first authors and corresponding authors.

Footnotes

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

Beijing Jishuitan Hospital funds were received to support this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: employment.

References

- 1.He J, Gu D, Wu X, et al. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1124–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999. JAMA 2001;285:1571–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA 2003;290:2443–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci JA, Stewart WF, Chee E, et al. Back pain exacerbations and lost productive time costs in United States workers. Spine 2006;31:3052–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo HR, Tanaka S, Halperin WE, et al. Back pain prevalence in US industry and estimates of lost workdays. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1029–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:21–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carragee EJ, Spinnickie AO, Alamin TF, et al. A prospective controlled study of limited versus subtotal posterior discectomy: short-term outcomes in patients with herniated lumbar intervertebral discs and large posterior annular defect. Spine 2006;31:653–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGirt MJ, Eustacchio S, Varga P, et al. A prospective cohort study of closed interval computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging after primary lumbar discectomy: factors associated with recurrent disc herniation and disc height loss. Spine 2009;34:2044–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimura N, Dennison E, Willman C, et al. Epidemiology of chronic disc degeneration and osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine in Britain and Japan: a comparative study. J Rheumatol 2000;27:429–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Yang X, Li Y, et al. A status survey on disease constitution and cost of inpatients in Xintian Central Township Health Center in Lintao County of Gansu province, 2008–2010 (in Chinese). Chin J Evid-Based Med 2011;11:131–7 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suri P, Miyakoshi A, Hunter PJ, et al. Does lumbar spinal degeneration begin with the anterior structures? a study of the observed epidemiology in a community-based population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Leading Group Office of Beijing of the Sixth National Census, Bureau of Statistics of Beijing, Survey Organization of Beijing of National Bureau of Statistics of China. The report of sixth national census of Beijing city. 2011. Available at: http://www.bjstats.gov.cn/rkpc_6/pcdt/tztg/201105/t20110504_201368.htm Accessed June 10, 2014

- 13.Battié MC, Videman T, Laura E, et al. Occupational driving and lumbar disc degeneration: a case control study. Lancet 2002;360:1369–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riihimäki H, Viikari-Juntura E. Back and limb disorders. In:McDonald C, Wheatley M, eds. Epidemiology of Work Related Diseases. London, United Kingdom: BMJ Books; 2000:233–43 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong A, Anderson J, Roche J. A pilot study of the prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in elite athletes with low back pain at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:263–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans W, Jobe W, Seibert C. A cross-sectional prevalence study of lumbar disc degeneration in a working population. Spine 1989;14:60–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Meng Y, Sun G. The epidemiological investigation of computer use status and cervical lumbar spondylosis in civil servants (in Chinese). Chin J Clin Health 2010;13:596–9 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large population-based survey. Am J of Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study Group. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1090–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li N, Xue Q, Zhang Y, et al. Risk factors for lumbar osteoarthritis in the middle-aged and elderly populations in six cities of China: data analysis of 6128 persons. JCRTER (in Chinese) 2007;11:9508–12 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battié MC, Videman T, Parent Lumbar disc degeneration: epidemiology and genetic influences. Spine 2004;29:2679–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanayama M, Daisuke T, Takahashi T, et al. Cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study of lumbar disc degeneration in 200 healthy individuals. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;11:501–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Like M, Solovieva S, Lamminen A, et al. Disc degeneration of the lumbar spine in relation to overweight. Int J Obes 2005;29:903–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostova V, Koleva M. Back disorders (low back pain, cervicobrachial and lumbosacral radicular syndromes) and some related risk factors. J Neurol Sci 2001;192:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanuele JC, Abdu WA, Hanscom B, et al. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine 2002;27:306–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rannou F, Corvol MT, Hudry C, et al. Sensitivity of annulus fibrosus cells to interleukin 1 beta. Comparison with articular chondrocytes. Spine 2000;25:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Sun Z, Zhang Z, et al. Risk factors for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation in Chinese population: a case-control study. Spine 2009;34:e918–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lings S, Leboeuf-Yde C. Whole-body vibration and low back pain: a systematic, critical review of the epidemiological literature 1992–1999. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2000;73:290–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelsey JL, Hardy RJ. Driving of motor vehicles as a risk factor for acute herniated lumbar intervertebral disc. Am J Epidemiol 1975;102:63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heliövaara M. Occupation and risk of herniated lumbar intervertebral disk and sciatica leading to hospitalization. J Chron Dis 1987;40:259–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen MV, Tüchsen F, Ørhedem E. Prolapsed cervical intervertebral disc in male professional drivers in Denmark, 1981–90: a longitudinal study of hospitalizations. Spine 1996;21:2352–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadjipavlou AG, Tzermiadianos MN, Bogduk N, et al. The pathophysiology of disc degeneration: a critical review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:1261–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams MA, Bogduk N, Burton K, et al. The Biomechanics of Back Pain. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2012 [Google Scholar]