Abstract

The precise spatial control of cell adhesion to surfaces is an endeavor that has enabled discoveries in cell biology and new possibilities in tissue engineering. The generation of cell-repellent surfaces currently requires advanced chemistry techniques and could be simplified. Here we show that mucins, glycoproteins of high structural and chemical complexity, spontaneously adsorb on hydrophobic substrates to form coatings that prevent the surface adhesion of mammalian epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and myoblasts. These mucin coatings can be patterned with micrometer precision using a microfluidic device, and are stable enough to support myoblast differentiation over seven days. Moreover, our data indicate that the cell-repellent effect is dependent on mucin-associated glycans because their removal results in a loss of effective cell-repulsion. Last, we show that a critical surface density of mucins, which is required to achieve cell-repulsion, is efficiently obtained on hydrophobic surfaces, but not on hydrophilic glass surfaces. However, this limitation can be overcome by coating glass with hydrophobic fluorosilane. We conclude that mucin biopolymers are attractive candidates to control cell adhesion on surfaces.

Keywords: mucin coatings, cell patterning, cell repellent surface, mucus, cell adhesion

Introduction

Adhesion of mammalian cells to synthetic materials is the first, necessary step in many cellular processes including migration, differentiation and activation of the foreign body reaction, a process that leads to the rejection of implanted materials1. Controlling the adhesion of mammalian cells to solid surfaces is thus of relevance for biomaterials science, as it can improve overall biocompatibility of implants and facilitate tissue formation in tissue engineering applications. For example, spatial control of pre-muscle myoblast adhesion can accelerate the formation of contractile muscle tissue and facilitate the study of cell alignment2 and differentiation3. Tuning cell adhesion to surfaces is also becoming increasingly important for cell biologists. Controlling cell shape and positioning on substrates has facilitated the study of tissue formation and organization, cell-cell interactions4 and has enabled well-controlled co-culture experiments5.

One important aspect of cell patterning is the coating of substrates with cell-repellent molecules in spatially confined ways. Effective cell repulsion can be achieved with a number of different synthetic molecules including polyethylene glycol (PEG) and zwitterionic molecules6. Additionally, surface-immobilized biopolymers such as hyaluronic acid7, alginic acid8 or carboxymethyl-dextran9, can also be repulsive towards cells. However, these molecules typically do not spontaneously adsorb on surfaces with sufficient density to exert effective cell-repulsion. Common strategies to overcome this limitation are the addition of surface-anchoring groups to the cytophobic molecules10–12 or the chemical activation of the surface to retain the cytophobic molecules to the surface for extended periods of time. These efforts can be time-consuming and costly. Surface grafting in particular is limited to few substrates such as gold or silicon and often requires the use of organic solvents, acids and other hazardous chemicals13. Hence, it is desirable to develop more efficient and biocompatible strategies to control the adhesion of mammalian cells to surfaces.

Mucin biopolymers constitute the main gel-forming components of the mucus barrier14 and are interesting candidates for regulating mammalian cell adhesion. Secreted mucins are densely glycosylated, thread-like molecules with random coil configurations15,16, which can reach molecular weights of up to tens of MDa. The diversity of chemical groups provided by the protein backbone and glycan side chains enable mucins to adsorb to a number of different substrates, including polystyrene, gold, and silica. On polystyrene, which is used for flasks, multi-well plates and tubes, mucins adsorb through their exposed hydrophobic protein core portions while protruding their hydrophilic and glycosylated domains into the aqueous solvent17. This configuration results in highly hydrophilic18–20 and hydrated monolayers, with around 95% of the adsorbed mass being water21. Of note is that mucin coatings are able to decrease the adhesion of certain bacteria19,20, neutrophils and fibroblast22–24, but their use in mammalian cells patterning has not been explored. Here, we investigate the potential of mucin-based coatings to pattern the attachment of mammalian cells.

UV and photolithography based patterning techniques such as micro stamping25,26 and local etching27,28 or activation29 of cell-repellent polymer coatings are routinely used by cell biologist and tissue engineers. An even more accessible and low cost alternative to UV and photolithography is Micro Molding in Capillaries30, which is based on placing a mold (often poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS)) with geometrically defined open channels on a surface. Cell-repellent molecules are distributed through the channels, adsorb to the surface and leave behind patterned cell-repellent coating once the mold is removed. Here we seek to combine this relatively simple patterning technique with the use of mucin biopolymers to explore novel protocols for cell patterning.

Our work shows that mucins can readily adsorb to hydrophobic substrates and prevent cells from adhering to, and spreading, on these substrates. Using a simple microfluidic device to pattern mucin coatings, precise control of cell positioning and attachment can be achieved. Moreover, the mucin pattern can be maintained over 14 days in serum-containing media and is stable enough to spatially confine myoblasts during their differentiation into myoblast over a 7-day culture. Last, the repulsive effect toward cells is likely mediated by mucin-associated glycans because their removal eliminates the cell-repellent effect. Although cell-repellent mucin coatings could not be generated on hydrophilic glass surfaces, modifying the glass surface with a hydrophobic fluorosilane layer before generating the mucin coating recovered the effect. This makes the technology interesting for a wide variety of materials and applications.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

Commercial bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM, Sigma-Aldrich; lot 039K7003) and pig gastric mucin (PGM, Sigma-Aldrich, lot 116K7040) were dialyzed against water (Spectra/Por dialysis membrane; 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff; Spectrum Labs) to remove impurities31,32, before lyophilization for storage. Skim milk (Becton Dickinson), fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich), bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) and lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as received. Pig gastric mucins were purified in lab as reported 33, omitting the cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation.

BSM, fibronectin, BSA and lysozyme were labeled with Alexa488 or Rhodamine Red fluorophore using the carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester amine-reactive derivatives (Invitrogen). Briefly, the proteins were dissolved in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (0.2 M, pH 8.5) and incubated with the dye at a protein-to-dye mass ratio of 1:10 for 1 hour at room temperature. The excess dye was removed either by centrifuge filtration (Pall, 10kDa MWCO) for fibronectin and BSM, or in desalting columns (PD-10, GE Healthcare Lifesciences) for BSA and lysozyme.

PDMS mold fabrication for surface patterning

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow corning, USA) molds were fabricated by curing the prepolymer on silicon masters patterned with SU-8 photoresist (SU-8 2050, MicroChem, MA, USA) using conventional photolithography. The masters used for patterning had recessing features, which resulted in PDMS replicas with the opposite sense. To assist in removal of cured PDMS from the masters, the SU-8 masters are silanized by exposure to the vapor of 1,1,2,2,-tetrahydrooctyl-1-trichlorosilane, CF3(CF2)6(CH2)2SiCl3 for overnight. To cure the PDMS prepolymer, a mixture of 10:1 silicon elastomer and the curing agent was poured on the master and placed at 65°C for 2 hours. The PDMS replica was then peeled from the silicon masters.

Generating micropatterned mucin coatings

The PDMS molds used for patterning were composed of a single microchannel (4 mm wide, 6 cm long, 50 μm high), posts of selected design and size, an outlet, and an inlet. The device was placed on an untreated polystyrene surface (Thermo Scientific, 267061) and gentle pressure was applied to form a reversible seal to the surface. The channel was filled with a 20 mM HEPES buffer solution (pH 7.4) through suction at the outlet, filling in the solution from a reservoir placed at the inlet. Once the channel was filled, the buffer was exchanged for a 1mg/mL solution of mucin (BSM in 20 mM HEPES; pH 7.4), which was left in the channel for 30 minutes to enable mucin adsorption. Unbound mucin was flushed from the device with washing buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) before the microfluidic device was peeled off the substrate and the coating immersed in washing buffer until used. For the quantification of protein adsorption and cell adhesion, the mucin coatings were generated in untreated polystyrene 96 well plates (Becton Dickinson, 351172). Prior to seeding cells on the coatings, the surfaces were treated with 10μg/mL fibronectin in PBS for 30 minutes to promote cell adhesion and differentiation.

Cell culture

HeLa cells, C2C12 myoblasts and NIH-3T3 fibroblasts (ATTC CCL92) were maintained at sub-confluency in T25 flasks with DMEM media supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Invitrogen) and 1 % antibiotics (25 U/mL penicillin, 25μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were detached using trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen). The detached cells were plated at a density of 45,000 cells/cm2 on mucin coatings or plastic controls. After 24 hours, the cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to the Live/Dead Cell Viability Asssay (Invitrogen) to determine viability.

To monitor C2C12 differentiation, the cells were grown for 2 days in growth medium (DMEM + 10% FBS), followed by 5 days in differentiation medium (DMEM + 1 % Horse Serum), which was exchanged every two days. Thereafter, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed for 10 minutes in 3% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). First, actin was labelled with phalloidin-rhodamine (Invitrogen). Then troponin T was labelled by immune fluorescence using a primary anti-Troponin T antibody (Goat Anti Mouse antibody, Santa-Cruz sc-365575) and a fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody (Donkey anti Mouse, Santa-Cruz, sc-2099). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (Santa-Cruz), which was present in the mounting solution.

Cell adhesion was measured using the CyQuant DNA quantification kit (Invitrogen). In brief, cells were seeded in 96 well plates. After 24 hours, non-adherent cells were removed by washing the wells twice with 200μL of PBS. The wells were air dried and frozen at −80 °C overnight. Then the plates were thawed and 100 μL of CyQuant reagent was added to the wells before the fluorescence intensity (Exc480/Em520 nm) was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (Spectramax M3, Molecular Device).

Deglycosylation of mucins

BSM was deglycosylated by treatment with trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFMS), followed by oxidation and beta-elimination of the residual sugars as previously described34. Briefly, 5mg of BSM was mixed with 375μL of ice-cold TFMS (Acros Organics) containing 10% (v/v) anisole (Sigma-Aldrich) and stirred on ice. After 2 hours the solution was neutralized by the addition of a solution containing 3 parts pyridine (Alfa Aesar), 1 part methanol and 1 part water. The solution was dialyzed against water for 2 days using a 20kDa MWCO membrane (Thermo Scientific). NaCl and acetic acid were added to the solution to a final concentration of 0.33M and 0.1M, respectively and pH adjusted to 4.5 with NaOH. The oxidation step was initiated by adding NaIO4 to a final concentration of 100mM, and incubated at 4°C for 5 hours in the dark. The unreacted periodate was then destroyed by adding a ½ volume of “neutralizing solution” (400mM Na2S2O3, 100mM NaI, 100mM NaHCO3). The beta elimination of the remaining glycans was started by adjusting the pH to 10.5 using 1 M NaOH. After a 1-hour incubation at 4 °C, the solution was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against a 5mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 10.5) and further dialyzed against ultrapure water for 2 days. The resulting apo-mucin solution was then concentrated and dissolved in the appropriate buffer. The deglycosylation was verified by performing a Periodate-Schiff assay35.

Characterization of apo-mucin coatings by QCM-D

Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation monitoring was used (QCM-D, E4 system, Q-Sense, Sweden) to characterize the apo-mucin coatings. The crystals were purchased coated with polystyrene (QSX305, Q-sense, Sweden). All QCM-D experiments were carried out in no-flow conditions. The crystal vibration was followed at its fundamental frequency (about 5Mhz) and the 6 overtones (15, 25, 35, 45, 55 and 65Mhz). Changes in the resonance frequencies, and in dissipation of the vibration once the excitation was stopped, were followed at the 7 frequencies. Shifts in frequency are related to changes in adsorbed mass (due to adsorbed polymers, water and ions), whereas changes in dissipation are influenced by the mechanical properties of the adsorbed layer. The mucin coatings are highly hydrated, hence, the dissipation values are significant and the Sauerbrey relation, which relates frequency to the adsorbed mass through a linear relationship does not apply. The Voigt based model was used to estimate the hydrated thickness36. The density of the adsorbed layer was fixed at 1050 kg m−3, which lies between that of pure water (1000 kg m−3) and pure protein (1350 kg m−3). This approximation was validated for a related system37 and was reported to have minimal impact on the final modeled thickness38,39.

Fluorosilane coating

Glass microscope slides were coated with fluorosilane as reported40. Microscope slides (VWR Scientific) were sonicated in a 4vol% Micro-90 cleaning solution (International Products) for 15 min, followed by two subsequent steps of sonication in Milli-Q water. After drying with compressed air, glass slides were placed and sealed in a Teflon canister with one drop of 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluoro-decyl-trichloro-silane (Sigma-Aldrich). The Teflon canisters were in a sealed glove box under dry nitrogen atmosphere during the fluoroalkyl silane treatment, and then placed in a heater overnight at 110°C.

Microscopy

For imaging, the coatings were submerged in PBS (pH 7.4), using an Observer Z1 inverted fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a 10× 0.3 NA objective (Zeiss, Germany). Image analysis was performed with built-in plugins of the ImageJ software.

Quantification of mucin adsorption

To measure the quantity of adsorbed BSM on polystyrene, glass and fluorosilane coated glass surfaces, a 50μL drop of fluorescently labeled mucins (1mg/mL in PBS) was placed onto each surface and the mucin and was allowed to adsorb for 30 minutes. The slides were rinsed and kept in PBS for observation. Each surface was prepared in duplicate, and 10 images were taken per condition. The fluorescence intensity was average over all images taken per condition.

Results and discussion

Mucins coatings Prevent adhesion of Several Cell types

To test if mucins are suitable substrates to regulate cell adhesion in vitro, we generated mucin coatings by placing a 0.1% mucin solution in contact with a polystyrene surface. We used commercial bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM) and pig gastric mucin (PGM), as well as in-lab extracted PGM, which form thick coatings on polystyrene when hydrated (see supplementary information 1).

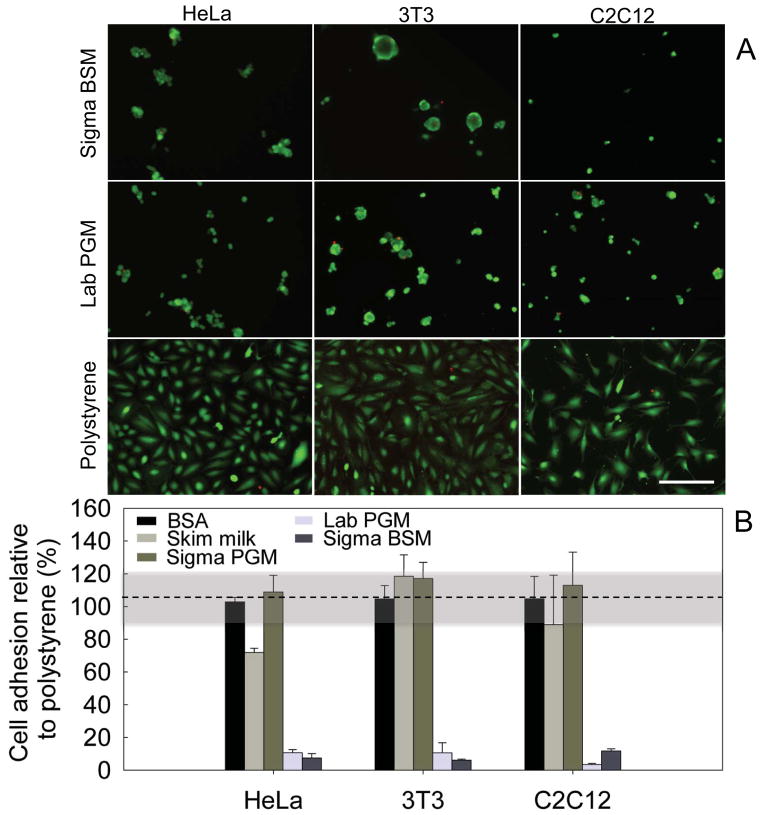

We analysed the effects of these mucin coatings toward three cell lines: HeLa epithelial cells, 3T3 fibroblasts, and C2C12 myoblasts. After 24 hours, all three cell-types only sparsely colonized the mucin coatings compared to the uncoated polystyrene surface. In addition, those cells that attached to the mucin coatings were typically rounder in shape than the cells on the uncoated surface. A simultaneous calcein and EthD-1 staining suggests that the cells on the mucin coatings were still alive (Figure 1A), and that the mucin coatings were not toxic toward the cells.

Figure 1. Mucin coatings are cytophobic.

(A) HeLa epithelial cells, 3T3 fibroblast cells and C2C12 myoblasts were seeded on a polystyrene surface, or on coatings generated from BSM (Sigma) or PGM (in-lab purified) and labeled with a live (green)/dead (red) stain. Scale bars: 200μm.” (B) Quantification of cell adhesion on mucin coatings generated with commercial BSM and PGM (Sigma BSM/PGM), in-lab purified PGM (Lab PGM), Skim milk, and BSA. The highlighted region between 90–120% is the standard deviation of the reference adhesion to polystyrene.

A quantification of adherent cells showed that both BSM and native in-lab purified PGM coatings reduced adhesion of all three cell types by nearly 90%, compared to polystyrene (Figure 1B). In contrast, the common blocking agents bovine serum albumin (BSA) and skim milk (Figure 1B) did not significantly reduce cell adhesion. These data show that BSM and in-lab purified PGM biopolymers are both excellent candidate molecules to create cell-repelling coatings. Of note is that commercial PGM (from Sigma-Aldrich) did not exert the cell-repulsive effect that was observed with the two other mucin types. We speculate that the industrial purification procedure may result in an altered biochemistry of the PGM, which compromises their function. Indeed, as opposed to in-lab purified PGM, Sigma PGM have lost their ability to efficiently gelate at low pH41.

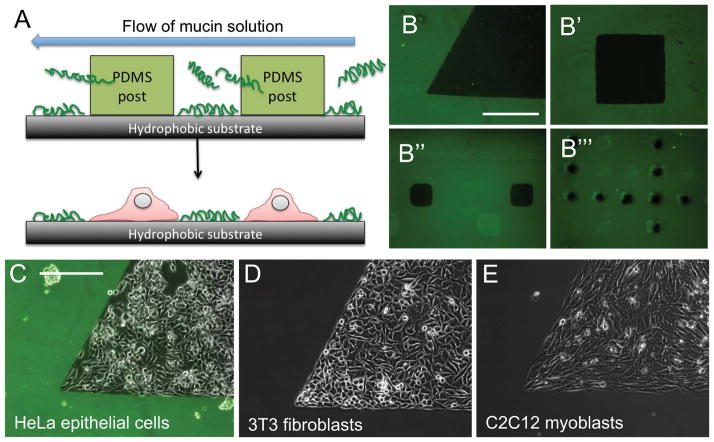

Spatially defined micropatterned mucin coatings with durable cell-repulsion

Based on these robust anti-adhesive properties, we probed the potential of mucin coatings for cell patterning applications. For this purpose, we adapted micromolding in capillaries30 technology to generate BSM coatings. In brief, we used a microfluidic channel that contained vertical removable posts which blocked mucin adsorption to the polystyrene surface at designated regions (Figure 2A). The mucins were flown into the channel where they adsorbed to the unmasked regions of the polystyrene bottom. Then the posts were removed to uncover the uncoated surface. With this technique, patterns of various shapes and dimensions (between tens and hundreds of micrometers) could be generated in less than 30 minutes. Figure 2B shows different geometries of mucin coatings in which fluorescently labeled mucins were used for visualization by epifluorescent microscopy (Figure 2B). When cultured with cells, the mucin-coated areas remained distinctly cell-free, while the mucin-free areas were densely populated by all three cell types tested (Figure 2C, D and E). The sharp transition between cell-covered and uncovered zones suggests that the cell-repulsive effect of the patterned mucin coatings has high spatial accuracy. From a practical perspective it is interesting to note that the coatings can be dried and rehydrated without losing their cytophobic effect (see supplementary information 2). This is particularly important if these surfaces are to be sterilized and stored before use.

Figure 2. Mucin coatings for cell patterning.

(A) Mucin coatings were patterned using a microfluidic device with posts masking defined areas of the surface. (B) Patterns of mucin-free areas (in black) can be generated in different sizes and shapes. When seeded on the patterned surfaces, the epithelial cells (C), fibroblasts (D) and myoblasts (E) accumulated in the uncoated regions, avoiding the mucin coatings. Scale bars: 250μm.”

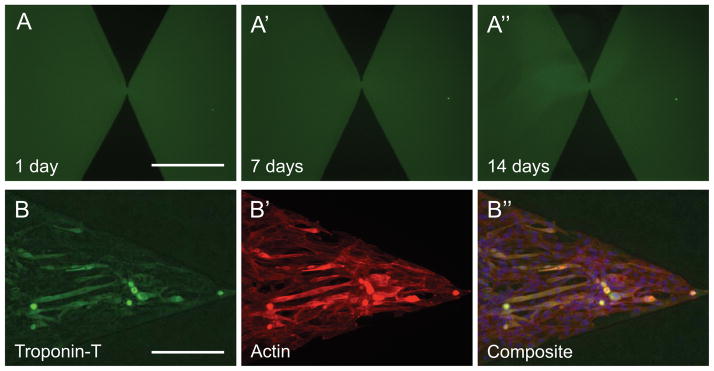

To test the stability and functionality of mucin coatings over time, we monitored patterned fluorescent mucin coatings over 14 days in cell-free culture media. The patterns showed no obvious signs of deterioration: both the fluorescence intensity and the sharp edges of the patterns remained stable (Figure 3A, A′ and A″). To test for loss of cytophobicity over time, C2C12 myoblast cells were seeded on the patterned coatings and monitored over 7 days. Over this period, the cells remained confined within the mucin-free regions (Figure 3B″) which suggests that the cell-repulsion effect was maintained despite the tendency of C2C12 cells to migrate and secrete extracellular matrix and proteases. Immunofluorescence for Troponin T, an early marker for myotube differentiation42 (Figure 7B), and actin (Figure 7B′) showed that troponin T-positive myotubes emerged after 7 days. These data suggest that in standard cell culture conditions, mucin coatings preserve their cytophobic effect toward C2C12 cells, while allowing for basic cellular differentiation.

Figure 3. Mucin coatings and their cytophobic effect are robust.

(A) Mucin patterns immersed in cell culture media for 14 days showed no alteration in their shape or fluorescence intensity. C2C12 myoblasts that were cultured on the coatings for 7-days expressed troponin-T, which is a marker for early myogenic differentiation. (B′) Actin staining reveals that cells are confined within the pattern. A Troponin-T/Actin overlay is shown in (B″). Scale bars: 250μm.”

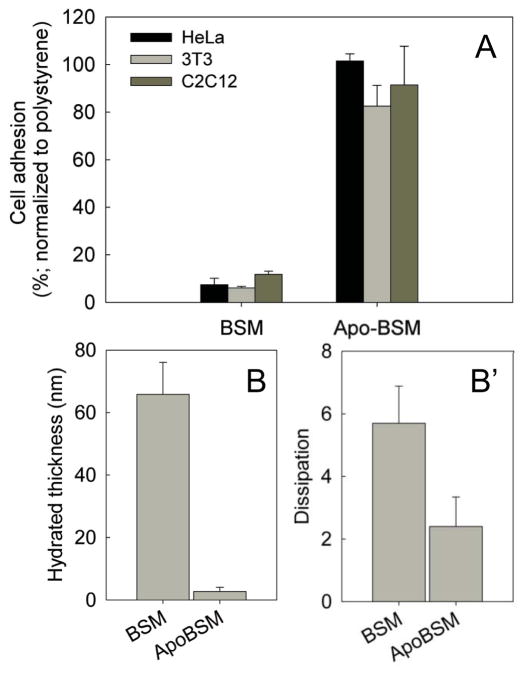

Mucin-linked glycans contribute to cell-repulsion

To better understand the molecular origin of mucin-mediated cell-repulsion, we focused our attention on the features that distinguish mucins from other proteins such as albumin that do not generate cell-repellent coatings. Mucins are largely linear molecules that are densely coated with O-linked glycans. These glycans contribute to mucin’s for molecules’ extended structure and ability to form hydrogels43. We hypothesized that mucin-associated glycans also play a major role in producing the cell-repellent effect. We tested this by chemically removing the glycans from the mucin protein core, then testing cell adhesion on glycan-free mucin (apo-mucins) coatings. As depicted in Figure 4A, coatings consisting of apo-mucins lost the capability to reduce cell adhesion, confirming that mucin-linked glycans are necessary for mucin-mediated cell repulsion.

Figure 4. Mucin glycans are essential for the cytophobic effect.

(A) Coatings generated from de-glycosylated mucins (Apo-BSM) failed to repel all three cell types tested. Glycan removal from mucins resulted in altered properties of the coatings as probed by QCM-D measurements. (B) Glycosylated mucins yielded thicker coatings and more (B′) dissipation, which is diagnostic for soft materials.

To analyse basic biophysical parameters of mucin and apo-mucin coatings we used quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D), a technique that provides information about the thickness and softness of an absorbed monolayer. QCM-D analysis (Figure 4B) revealed that coatings from apo-mucins are considerably thinner compared to coatings from fully glycosylated mucins, with thicknesses of 3 (± 1.5nm) and 66nm (± 10nm) respectively. Moreover, apo-mucin coatings showed a reduced dissipation of the acoustic wave that QCM-D uses to probe the coating properties (Figure 4B′) and an increase in shear and viscosity parameters obtained by QCM-D data fitting (SI3) compared to native mucin coatings, indicating that the removal of glycans results in stiffer and more compacted monolayers. This is in line with the transition of mucin molecules from an extended to a more globular and thus compact structure upon deglycosylation 15,16. Together, these data show that mucin-associated glycans contribute to the cell repellent effect. The mechanism underlying the role of mucin-associated glycans remains unclear, but some commonalities with synthetic cell-repellent systems such as polyethylene glycol grafted surfaces 44–46 emerge. In particular, we speculate that the cell repellent effect of mucin coatings could originate from a high level of hydration and steric effects mediated by the glycans.

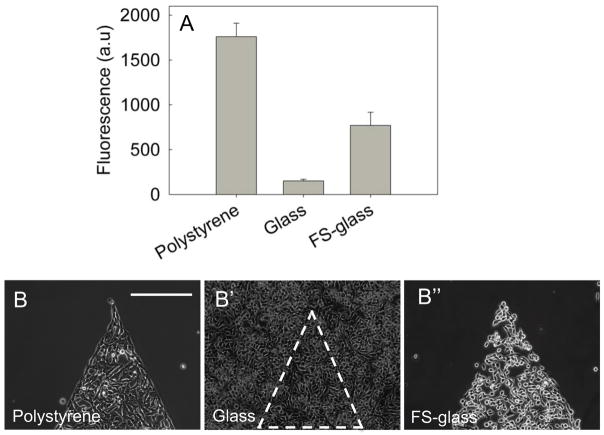

Hydrophobic Surfaces Promote the Formation of Mucin-coatings

So far, we have discussed mucins in the context of polystyrene surfaces, but for cell biology studies and biomedical applications, this technique must be applicable to a wider array of materials. Hence, we tested if mucin coatings can also be created on glass, which is a material commonly used for cell culture and microscopy. Using fluorescently labeled BSM, we first investigated the ability of mucins to adsorb to a glass surface. Fluorescence measurements indicated that mucins adsorbed with a lower surface density on glass compared to polystyrene (Figure 5A). Reduced mucin adsorption on glass was correlated with a lack of cell repulsion compared to the coatings on polystyrene (Figure 5B and 5B′). This finding is in accordance with previous studies, which show that mucin adsorbs in thick and strongly bound layers on hydrophobic surfaces, while layers can be sparser on hydrophilic substrates 47,48. Since glass is more hydrophilic than polystyrene, surface chemistry could be the main reason for the inefficient mucin adsorption. If this is the case, it should then be possible to restore efficient mucin adsorption by rendering the glass surface hydrophobic. We coated the glass with fluoroalkyl silane by vapor deposition and found that mucin adsorption increased (Figure 5A). Moreover, the presence of the fluorosilane coating restored the cytophobic effect, with cells excluded from mucin coated areas (Figure 5B″).

Figure 5. Mucin coatings form preferentially on hydrophobic surfaces.

(A) The relative amount of mucins adsorbed to various surfaces was estimated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of coatings generated with fluorescently labeled mucins. Mucins failed to adsorb on glass efficiently, however, treating glass with fluorosilane (FS-glass) reversed this effect and promoted the formation of mucin coatings. Accordingly, mucin-mediated cell-repulsion was observed on polystyrene (B) and on fluorosilane-treated glass (B″), but not on untreated microscope glass slides (B′).

Conclusions

We have shown that mucins, the basic constituents of the mucus barrier, are excellent biological substrates for the generation of spatially precise and patterned coatings to control cell adhesion and differentiation. Expanding on earlier reports on mucins’ ability to repel mammalian cells, we have presented an analysis of the cytophobic effect of mucins against a range of different cell lines, their use in microfluidic-based cell patterning, and the molecular mechanism responsible for the cytophobic effect. The mucin coatings present a fast, accessible, cheap and effective way of controlling cell adhesion, and provide great flexibility when coupled to patterning techniques. From cell biology to biomaterial and tissue engineering studies, these coatings could be used to control cell adhesion with high spatial resolution. Importantly, robustness against drying will allow these coatings to be stored and sterilized. Beyond these technological applications, these results are intriguing from a basic science perspective as they lead to interesting questions regarding cell-mucus interaction in vivo. For example, our results suggest that interaction between mammalian cells and the natural mucus matrix could be independent of adhesion, and thus very different from connective tissue extracellular matrices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Rubner and Robert Cohen for their valuable comments. This work made use of the MRSEC Shared Experiment Facilities supported by the National Science Foundation under award number DMR – 819762. This work was made possible by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship “BIOMUC” (to TC), NIH grant 1R01GM100473 (to RS), NSF grant OCE-0744641-CAREER (to RS), NSF grant IOS-1120200 (to RS), the MRSEC program of the National Science Foundation under Award DMR-0819762. H. L. (to JA), the Samsung Scholarship program (to JA), the MIT startup funds (to KR), and a Junior Faculty award for the use of the CMSE MRSEC facilities (to KR).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting information to this manuscript includes mucin (both PGM and BSM) adsorption kinetics on polystyrene surface as measured by QCM-D (SI 1), measurement of cell repulsion effect of the BSM coating after a dehydration/rehydration cycle (SI 2) and a table containing the modeled viscoelastic parameters of the QCM-D data fitting (SI 3). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan LQ, Ronaldson K, Park M, Taylor G, Zhang Y, Gimble JM, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:12295–12300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103834108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popescu DC, Lems R, Rossi NAA, Yeoh CT, Loos J, Holder SJ, Bouten CVC, Sommerdijk NAJM. Adv Mater. 2005;17:2324–2329. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng Q, Duchemin-Pelletier E, Deshiere A, Balland M, Guillou H, Filhol O, Théry M. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:1506–1511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106377109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda J, Khademhosseini A, Yeh J, Eng G, Cheng J, Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1479–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan S, Weinman CJ, Ober CK. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:3405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morra M, Cassineli C. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1999;10:1107–1124. doi: 10.1163/156856299x00711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao X, Pettit ME, Conlan SL, Wagner W, Ho AD, Clare AS, Callow JA, Callow ME, Grunze M, Rosenhahn A. Colloids Surf, B. 2009;10:907–915. doi: 10.1021/bm8014208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean KM, Johnson G, Chatelier RC, Beumer GJ, Steele JG, Griesser HJ. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2000;18:221–234. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenausis GL, Vörös J, Elbert DL, Huang N, Hofer R, Ruiz-Taylor L, Textor M, Hubbell JA, Spencer ND. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:3298–3309. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenan DJ, Walsh EB, Meyers SR, O’Toole GA, Carruthers EG, Lee WK, Zauscher S, Prata CAH, Grinstaff MW. Chem Biol. 2006;13:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Science. 2007;318:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown AA, Khan NS, Steinbock L, Huck WTS. Eur Polym J. 2005;41:1757–1765. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansil R, Turner BS. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;11:164–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shogren R, Gerken TA, Jentoft N. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1989;28:5525–5536. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerken TA, Butenhof KJ, Shogren R. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1989;28:5536–5543. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kesimer M, Sheehan JK. Glycobiology. 2008;18:463. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi L, Caldwell KD. Mrs Proc. 2011:599. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bushnak I, Labeed F, Sear R, Keddie J. Biofouling. 2010;26:387–397. doi: 10.1080/08927011003646809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L, Ardehali R, Caldwell KD, Valint P. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2000;17:229–239. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halthur TJ, Arnebrant T, Macakova L, Feiler A. Langmuir. 2010;26:4901–4908. doi: 10.1021/la902267c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bavington CD, Lever R, Mulloy B, Grundy MM, Page CP, Richardson NV, McKenzie JD. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;139:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandberg T, Carlsson J, Ott MK. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70:864–868. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol. 2000;12:229–239. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:356–363. doi: 10.1021/bp980031m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink J, Théry M, Azioune A, Dupont R, Chatelain F, Bornens M, Piel M. Lab Chip. 2007;7:672. doi: 10.1039/b618545b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillmore WS, Yousaf MN, Mrksich M. Langmuir. 2004;20:7223–7231. doi: 10.1021/la049826v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kikuchi Y, Nakanishi J, Nakayama H, Shimizu T, Yoshino Y, Yamaguchi K, Yoshida Y, Horiike Y. Chem Lett. 2008;37:1062–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bélisle JM, Kunik D, Costantino S. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3580. doi: 10.1039/b911967a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim E, Xia Y, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5722–5731. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandberg T, Blom H, Caldwell KD. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91A:762–772. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundin M, Sandberg T, Caldwell KD, Blomberg E. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;336:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Celli J, Gregor B, Turner B, Afdhal NH, Bansil R, Erramilli S. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1329–1333. doi: 10.1021/bm0493990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerken TA, Gupta R, Jentoft N. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1992;31:639–648. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilcoyne M, Gerlach JQ, Farrell MP, Bhavanandan VP, Joshi L. Anal Biochem. 416:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voinova MV, Rodahl M, Jonson M, Kasemo B. Phys Scr. 1999;59:391. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolatshahi-Pirouz A, Skeldal S, Hovgaard MB, Jensen T, Foss M, Chevallier J, Besenbacher F. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:4406–4412. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber N, Pesnell A, Bolikal D, Zeltinger J, Kohn J. Langmuir. 2007;23:3298–3304. doi: 10.1021/la060500r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrantes A, Santos O, Sotres J, Arnebrant T. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;388:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meuler AJ, Chhatre SS, Nieves AR, Mabry JM, Cohen RE, McKinley GH. Soft Matter. 2011;7:10122. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koevar-Nared J, Kristl J, Šmid-Korbar J. Biomaterials. 1997;18:677–681. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katagiri T, Yamaguchi A, Komaki M, Abe E, Takahashi N, Ikeda T, Rosen V, Wozney JM, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Suda T. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1755–1766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Vilar J. In: Oral Delivery of Macromolecular Drugs. Bernkop-Schnürch A, editor. Springer US; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen S, Li L, Zhao C, Zheng J. Polymer. 2010;51:5283–5293. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunkel G, Weinhart M, Becherer T, Haag R, Huck WTS. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:4169–4172. doi: 10.1021/bm200943m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szleifer I. Biophys J. 1997;72:595–612. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78698-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feldötö Z, Pettersson T, Ddinait A. Langmuir. 2008;24:3348–3357. doi: 10.1021/la703366k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi L, Caldwell KD. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;224:372–381. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.6724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.