Abstract

Dietary exposure to aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is detrimental to avian health and leads to major economic losses for the poultry industry. AFB1 is especially hepatotoxic in domestic turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), since these birds are unable to detoxify AFB1 by glutathione-conjugation. The impacts of AFB1 on the turkey hepatic transcriptome and the potential protection from pretreatment with a Lactobacillus-based probiotic mixture were investigated through RNA-sequencing. Animals were divided into four treatment groups and RNA was subsequently recovered from liver samples. Four pooled RNA-seq libraries were sequenced to produce over 322 M reads totaling 13.8 Gb of sequence. Approximately 170,000 predicted transcripts were de novo assembled, of which 803 had significant differential expression in at least one pair-wise comparison between treatment groups. Functional analysis linked many of the transcripts significantly affected by AFB1 exposure to cancer, apoptosis, the cell cycle or lipid regulation. Most notable were transcripts from the genes encoding E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm2, osteopontin, S-adenosylmethionine synthase isoform type-2, and lipoprotein lipase. Expression was modulated by the probiotics, but treatment did not completely mitigate the effects of AFB1. Genes identified through transcriptome analysis provide candidates for further study of AFB1 toxicity and targets for efforts to improve the health of domestic turkeys exposed to AFB1.

Introduction

Consumption of feed contaminated with mycotoxins can adversely affect poultry performance and health. Mycotoxins are estimated to contaminate up to 25% of world food supplies each year [1]. Due to potent hepatotoxicity and worldwide impacts, aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is one of the most important mycotoxins [2], [3]. The extreme toxicity of AFB1 in domestic turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) was demonstrated in 1960, when Turkey “X” Disease caused the deaths of over 100,000 turkeys and other poultry in England as a result of feeding AFB1-contaminated peanut-meal [4]. High doses of AFB1 can cause acute mortality; exposure at lower concentrations causes loss of appetite, liver damage, and immunosuppression [3]. Chronic dietary exposure to AFB1 and other aflatoxins also negatively affects poultry production traits, including weight gain, feed conversion, egg production and hatchability [5], [6], [7]. Consequently, aflatoxicosis is estimated to cost the poultry industry over $143 million in losses each year [1].

The toxicity of AFB1 is initiated by its bioactivation into the electrophilic exo-AFB1-8,9-epoxide (AFBO) [8]. Bioactivation is mediated by cytochrome P450s (P450s) located predominantly in hepatocytes, making the liver the primary target for toxicity [8]. The high sensitivity of domestic turkeys to AFB1 is likely due to a combination of efficient hepatic P450s and dysfunctional alpha-class glutathione S-transferases (GSTAs) that cannot conjugate and detoxify AFBO [9], [10], [11]. Although the cytochrome (CYP) and GSTA genes involved in the bioprocessing of AFB1 have been examined in the turkey, the impact of AFB1 on expression of other genes is not well understood. AFBO forms adducts with DNA and RNA, which can block transcription and translation and can induce DNA mutations [2], [8], [12]. Genes directly involved in these processes are likely candidates for expression changes in response to AFB1, along with genes that initiate or prevent apoptosis and carcinogenesis. In liver tissue from chickens (Gallus gallus), AFB1 is known to affect genes associated with fatty acid metabolism, development, detoxification, immunity and cell proliferation [13].

Once the impact of AFB1 on gene expression is understood, these changes can be used to evaluate methods directed at reducing and/or preventing aflatoxicosis. Probiotic gram-positive strains of Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium and Bifidobacterium can bind to AFB1 in vitro [14], [15], [16]. In chickens, injection of L. rhamnosus strain GG (LGG), L. rhamnosus strain LC-705 (LC-705), and P. freudenrieichii strain shermanii JS (PJS) into the intestinal lumen has also been shown to decrease AFB1 absorption into duodenal tissue [15], [17]. A probiotic mixture of LGG, LC-705, and PJS has therefore been proposed as a feed additive to inhibit AFB1 uptake from the small intestine and attenuate AFB1-induced toxicity in poultry. Given their susceptibly to AFB1, domestic turkeys provide an ideal model to test the ability of these probiotics to reduce aflatoxicosis.

This study was designed to examine the response of the turkey hepatic transcriptome to AFB1 and evaluate the chemopreventive potential of Lactobacillus-based probiotics using high throughput RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Corresponding phenotypic data from this challenge trial has been characterized in another report [18]. To our knowledge, only one study on swine has used RNA-seq to investigate the impacts of AFB1 exposure on gene expression [19]. Therefore, this analysis provides the first detailed examination of genes involved in turkey responses to AFB1 and modulation of its toxicity by probiotics.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All in-vivo work, including AFB1 challenge trial and sample collection, was performed at Utah State University (USU) in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facility according to a protocol (Number: 1001R) approved by the USU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All efforts were made to minimize suffering, such as dosage that would not cause mortality and euthanasia of poults by CO2 asphyxiation upon completion of the study.

Animals and Probiotic Preparation

One day-old male Nicholas domestic turkey poults (generously supplied by Moroni Feed Co., Ephraim, UT) were acclimated for 10 days at USU on a corn-based commercial diet (Moroni Feed Co.). The challenge trial was performed on young poults, rather than adults, since the activity of P450s and AFBO production is inversely related to age [20]. A probiotic mixture of lyophilized bacteria from Valio Ltd. (Helsinki, Finland) was used in the challenge trial. This mixture contained 2.3×1010 CFU/g of L. rhamnosus GG, 3.0×1010 CFU/g of L. rhamnosus LC-705, 3.5×1010 CFU/g of Propionibacterium freunchdenreichii sp. shermani JS, and 2.9×1010 CFU/g of Bifidobacterium sp., along with 58% microcrystalline cellulose, 27% gelatin and magnesium salt. Probiotic (PB) solution was prepared by directly suspending bacteria in phosphate buffered saline at a final concentration of 1×1011 CFU/mL as previously described [21].

AFB1 Challenge Trial

Poults (N = 40) were randomly assigned to one of 4 treatment groups (n = 10/group) (phosphate buffered saline control (CNTL), probiotic mixture (PB), aflatoxin B1 (AFB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB). After the 10 day acclimation period, turkeys in the PB and PBAFB groups were given 0.5 mL of PB (5×1010 CFU) daily by oral gavage from day 11 to day 31. Birds in the CNTL and AFB groups were administered 0.5 mL of phosphate buffered saline by oral gavage on day 11–31. The corn-based starter diet was fed to all poults in all treatments from day 11 to day 20. On day 21–31, turkeys in the CNTL and PB groups continued to receive the unaltered feed, while 1 ppm AFB1 was introduced into the diet fed to birds in the AFB and PBAFB groups. Poults were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation on day 31. Liver samples were collected directly into RNAlater (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX), perfused overnight at 4°C, and then stored at −20°C to preserve RNA. Phenotypic effects of aflatoxicosis, including weight gain, liver weight, histopathology, and serum analysis for this challenge trial are presented elsewhere [18]. Aflatoxicosis was verified by these measures for individuals in the AFB1-treated groups.

RNA Isolation and Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated by TRIzol extraction (Ambion, Inc.) from 3 tissue samples/treatment group (n = 12) and stored at −80°C to prevent degradation. gDNA contamination was removed from each RNA sample with the Turbo DNA-free™ Kit (Ambion, Inc.). RNA concentration and quality were assessed by denaturing gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). For each treatment group, individual DNase-treated RNA samples were pooled (n = 3) in equimolar amounts and RNA concentration in each pool was verified by spectrophotometry. Samples were pooled to maximize the depth of sequence collected from each treatment group, including rare sequences. Total RNA samples from the CNTL and AFB groups (8.5 µg) and the PB and PBAFB groups (6 µg) were submitted for sequencing on the Illumina Genome Analyzer II at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Four libraries (1 library/treatment group) were constructed according to the Illumina mRNA Sequencing Protocol. RNA integrity for each library was confirmed with the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were run on 4 flow cell lanes to produce 51 bp single-end reads. Sequencing at this depth required 2 flow cells (CNTL and AFB groups on flow cell 1 and PB and PBAFB on flow cell 2).

Read Filtering, Trimming, and Dataset QC Analysis

RNA-seq datasets for each library were filtered by BLAST aligning reads against common contaminating sequences, including bacteria gDNA and Illumina sequencing adaptors/primers. Using CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC bio, Cambridge, MA), reads were then trimmed for low quality (limit 0.05 for error probability, maximum of 2 ambiguities) and end trimmed (4 terminal bases on both 5′ and 3′ ends) to reduce library base composition biases and end quality dips. FastQC [22] was utilized to examine dataset quality before and after the trimming and filtering protocols.

De novo Assembly

The Velvet [23] and Oases [24] pipelines were used for de novo assembly of the corrected reads from all four datasets into predicted transcripts. Multiple sub-assemblies were generated in Velvet and Oases using a range of k-mer (hash) lengths (21, 23, 25, 27, 29, and 31) to construct contigs. A final merged assembly was created using the contigs from all six sub-assemblies as input sequence for Velvet and Oases with a k-mer value of 27. Default parameters were utilized for all assemblies, with the cutoffs for contig coverage and connection support set at 3. Corrected reads were mapped back to the final assembled predicted transcripts using BWA [25]. Counts of reads uniquely mapping to each transcript were determined using HTSeq in intersect-nonempty mode [26]. Reads that mapped to multiple transcripts were not included in coverage counts.

Transcript Annotation

Predicted transcripts were annotated by three BLAST alignments. Transcripts were first compared to cDNAs from the turkey genome build UMD 2.01 (www.ensembl.org) and assigned their coordinating NCBI Transcript Reference Sequence (RefSeq) IDs. A similar search of the chicken genome (Galgal 4.0) identified matches to chicken RefSeq mRNAs and a final BLAST comparison was performed to the UniProtKB Swiss-Prot protein database. For all three searches, BLAST hits were considered valid for bit scores ≥100 and the top hits were recorded. Transcripts that showed significant differential expression (DE) but lacked hits from the transcriptome-wide BLAST search were then aligned to the NCBI non-redundant nucleotide (NR) database. This allowed identification of un-annotated but previously characterized cDNAs, non-protein coding RNAs and other sequences only accessioned in the NR database.

Transcript Coverage Filtering

A coverage threshold of 0.1 read/million mapped was applied to filter predicted transcripts for sufficient read depth. To account for differences in the total number of mapped reads per treatment group, the minimum number of reads that must map to each transcript was determined separately in each treatment (Table S1). Transcripts were included in the transcriptome content and numbers for any treatment group in which they met this coverage threshold; lowly expressed transcripts were excluded only from the transcript list in the treatment(s) in which they fell below this threshold.

Differential Expression Analysis

Expression of each transcript in each treatment group was determined from read counts normalized with size scaling using the R package DESeq [27]. Since datasets were derived from RNA pools, DESeq estimated the within-treatment variation in expression of each transcript using its mean and the dispersion of its expression across all treatment groups (method = “blind” and sharingMode = “fit-only” settings). To prevent skewing of the means and variance estimates, all predicted transcripts were analyzed by DESeq rather than just the filtered set. Pair-wise comparisons for statistical significance based on a negative binomial distribution were made in DESeq using the mean and dispersion estimates and p-values were assigned. Expression in each treatment was compared to the CNTL group to determine the impact of AFB1 and/or PB. Two additional contrasts of the PBAFB group with the AFB and PB groups were also performed to investigate the ability of PB to mitigate AFB1 effects. Transcripts were considered to have significant DE if q-values (FDR adjusted p-values based on the Benjamin-Hochberg procedure) were ≤0.05. Scatter plots and heat maps generated in R were used to visualize the datasets and results of the expression analyses. Venn diagrams were created using a combination of BioVenn [28], Venny [29] and the R package VennDiagram 1.6.4 [30].

Genome and Functional Analysis

Filtered transcripts were aligned to the domestic turkey genome build UMD 2.01 using GMAP [31]. Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with significant DE transcripts were determined using Blast2GO V.2.6.6 [32], [33]. Further functional characterization of these DE transcripts was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA).

Results

RNA-seq Datasets

Sequencing of the four pooled libraries produced over 356 M 51 bp reads with an average quality score of 32.4 (Table 1) (as part of SRA project ID: SRP042724). Libraries run on the same flow cell generated similar read numbers, with 75 M reads collected for the CNTL library (SRX566381), 65 M for AFB (SRX569978), 111 M for PB (SRX570327) and 105 M for PBAFB (SRX570328). The number of sequence reads varied between flow cells, with more than 76 M additional reads produced on the second flow cell. Given this variation, normalization for library size was critical for accurate expression analyses. After read trimming and filtering (33.9 M reads removed), the corrected datasets were reduced by an average of 8.5 M reads. Average read length decreased to 42.9 bp, while average quality score per read increased to 33.3. Quality scores remained lower for reads collected on the first flow cell (CNTL and AFB datasets) than the second (PB and PBAFB) even after filtering and trimming (Figure S1). Box-plots demonstrate that the quality scores across base position in each corrected dataset were sufficiently high for reliable base calling (Figure S2). Cumulatively, all corrected reads comprise 13.8 Gb of usable sequence for transcriptome assembly (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for liver RNA-seq datasets.

| Number of Reads1 | ||||||||

| Filtering and Trimming | Average Read Length | Average Quality Score | CNTL | AFB | PB | PBAFB | Total | Total Sequence |

| Before | 51 bp | 32.4 | 75,218,798 | 64,798,923 | 111,295,859 | 105,158,981 | 356,472,561 | 18.2 Gb |

| After | 42.9 bp | 33.3 | 66,213,757 | 55,553,255 | 103,367,767 | 97,459,919 | 322,594,698 | 13.8 Gb |

| Discarded | 51 bp | ND2 | 9,005,041 | 9,245,668 | 7,928,092 | 7,699,062 | 33,877,863 | 4.4 Gb |

Treatment groups are control (CNTL), aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB).

Not determined (ND).

De novo Transcriptome Assembly

Final assembly of the transcriptome via the Velvet and Oases pipelines utilized 95.2% of the groomed RNA reads and generated 211 Mb of potential expressed sequence (Table 2). The assembly contains 174,010 predicted transcripts ranging in size from 200 to 39,213 bp. This number decreased to 169,387 transcripts after filtering out transcripts with insufficient coverage (Table 2; Table S1). Interestingly, the coverage threshold of 0.1 read/million mapped coincided with the most frequent read depth in each treatment (Figure S3). Although this filtering kept 99.9% of mapped reads, between 6.8% and 13% of expressed predicted transcripts fell below the threshold in each treatment group (Table S1).

Table 2. Summary of the de novo liver transcriptome assembly.

| Total Assembled | Above Coverage Threshold1 | ||

| Number of Reads | Mapped | 307,105,226 (95.2%) | 306,815,840 (95.1%) |

| Unmapped | 15,489,472 (4.8%) | 15,778,858 (4.9%) | |

| Total Number of Predicted Transcripts | 174,010 | 169,387 | |

| Transcript Length (bp) | Min | 200 | 200 |

| Mean | 1,213 | 1,238 | |

| Max | 39,213 | 39,213 | |

| N50 | 2,038 | 2,052 | |

| Total Residues (bp) | 211,012,448 | 209,738,998 | |

| Average GC Content/Transcript | 46.9% | 46.9% | |

| Transcripts Identified | Turkey | 85,435 (49.1%) | 85,052 (50.2%) |

| Chicken | 102,421 (58.9%) | 101,831 (60.1%) | |

| Swiss-Prot | 78,167 (44.9%) | 78,009 (46.1%) | |

| Total Known | 108,161 (62.2%) | 107,503 (63.5%) | |

| Unknown | 65,849 (37.8%) | 61,884 (36.5%) | |

Predicted transcripts were filtered according to a coverage threshold of 0.1 read/million mapped.

Fitting expectations for the turkey transcriptome, transcripts that met the coverage threshold had an N50 of 2.1 Kb and a GC content of 46.9% (Table 2). Mean filtered transcript length was 1.2 Kb, which is shorter but consistent with the average size of cDNAs in the turkey (1.7 Kb), chicken (2.5 Kb), duck (1.7 Kb) and zebra finch (1.4 Kb) Ensemble gene sets (genome assemblies UMD 2.01, Galgal 4.0, BGI duck 1.0 and taeGut 3.2.4). The majority (87.0%) of filtered liver transcripts ranged from 250 bp to 4 Kb (Figure S4). The few overly large transcripts have BLAST hits to known genes, but also contain repetitive sequences and expressed retrotransposons like CR1 repeats and LTR-elements. These large constructs were generated because the repeat-containing reads from across the genome cannot be uniquely distinguished during assembly even if discarded in mapping.

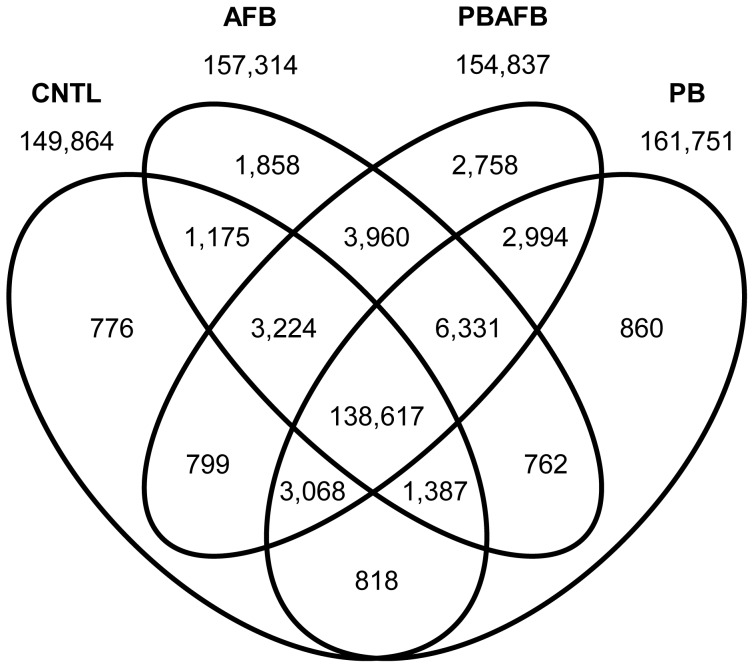

Most filtered transcripts (81.8%) were represented in all datasets; however, 24,518 (14.5%) were shared between only two or three treatments and 6,252 (3.7%) were unique to a single treatment (Figure 1). Of these unique transcripts, 76.9% did not match to previously annotated genes. BLAST screening identified only 63.5% of all filtered transcripts (Table 2). Although only 50.2% of filtered transcripts matched to known turkey mRNAs, 89.4% of transcripts mapped to the turkey genome (Table S2). This difference suggests that the majority of unknown transcripts represent splice variants, unannotated genes, and non-protein coding RNAs. Therefore, mapped transcripts provide a resource for genome annotation and improvement of gene models. The number of mapped transcripts per Mb of chromosome can be used to predict gene density. Microchromosomes, although small, were especially gene-rich. MGA18 and MGA27 had inflated relative gene content due to their poor representation in the genome assembly.

Figure 1. Comparative transcriptome content in domestic turkey liver.

The number of transcripts shared or unique to each combination of treatments after filtering is indicated in each section of the diagram. Totals for the control (CNTL), aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups are shown above each ellipse.

Differential Expression and Functional Analysis

Pair-wise comparisons of expression for predicted transcripts were performed using DESeq to normalize read counts, estimate dispersions, and perform significance tests. Since individuals were pooled prior to library construction, DESeq estimated within-group expression variance for each transcript using the relationship between the mean and the dispersion across all conditions. This decreases power and may limit to some extent the ability to identify significant differences in transcript abundance; estimation also increases type 1 errors. Therefore, the 803 transcripts with significant DE in at least one between-group comparison likely represent a subset of the total influenced by each treatment. Read counts from HTSeq, results from DESeq, BLAST annotations, and associated GO terms are provided for significant DE transcripts in each pair-wise comparison in Table S3. Data from DE analysis and BLAST screening for the complete list of predicted transcripts is available upon request.

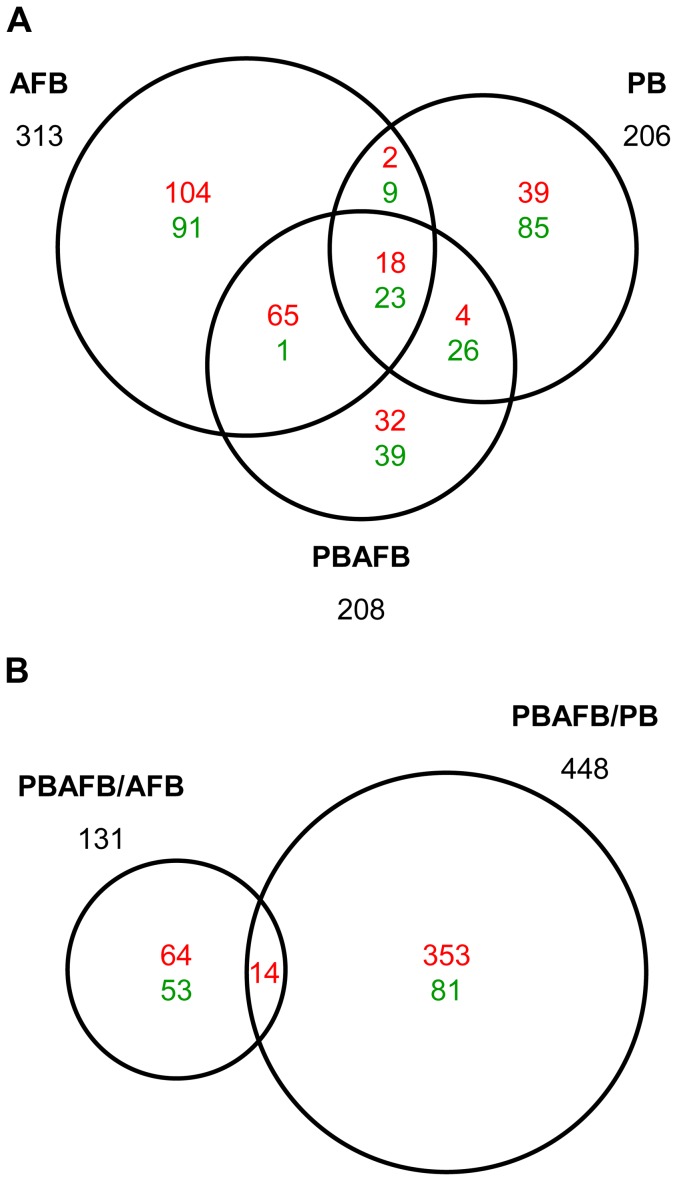

In pair-wise comparisons to the CNTL group, 538 transcripts were identified with significant DE in at least one other treatment (Figure 2A). Only 41 transcripts had significant DE in all three treatments (AFB, PB and PBAFB), including transcripts from apolipoprotein A-IV (APOA4) and alpha-2-macroglobulin (A2M). BLAST annotated 77.9% of these significant DE transcripts, including matches to sequences in the NR database (Table S3). Despite relatively high BLAST identification, Biological Process GO-terms could only be associated with 37.7% of these significant DE transcripts.

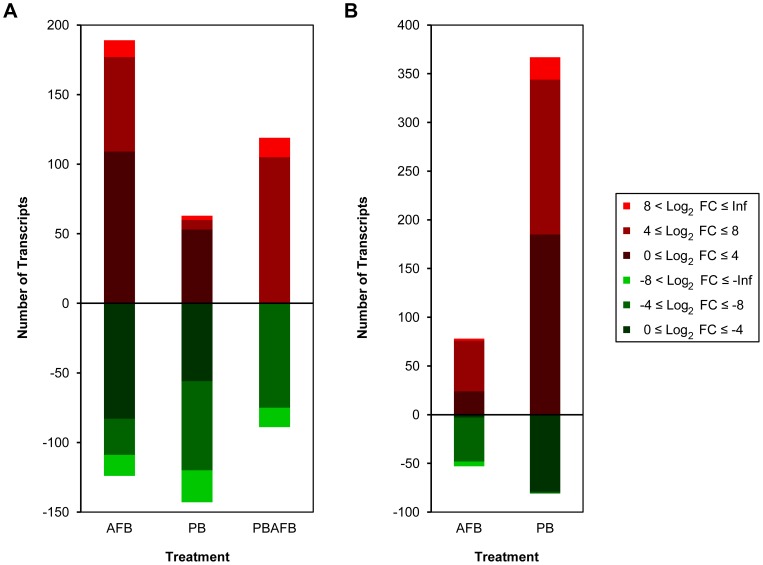

Figure 2. Liver transcripts with significant DE in each comparison between treatment groups.

Numbers in each section indicate predicted transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-value ≤0.05) that are shared between or unique to each comparison. Up-regulated transcripts are shown in red and down-regulated are shown in green. The total number of significant transcripts for each comparison is shown beside the corresponding circle. (A) Transcripts with significant DE when compared to the control (CNTL) group. (B) Transcripts with significant DE in inter-treatment comparisons (i.e. the probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) group compared to the aflatoxin B1 (AFB) or probiotic mixture (PB) group).

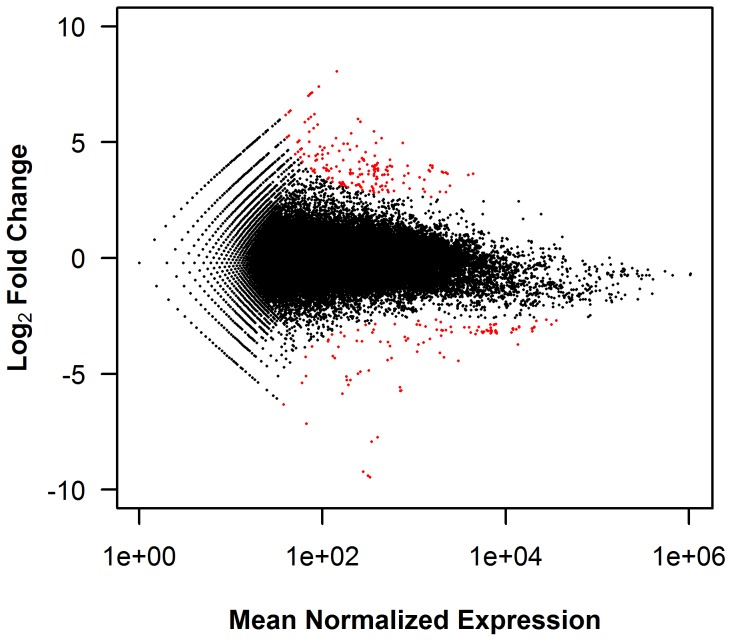

To visualize the significant transcripts, log2 fold change was plotted against mean normalized expression for each predicted transcript (Figure 3; Figure S5). In the AFB to CNTL comparison, transcripts with significant DE are located nearer the asymptotic curves for fold change in both the positive and negative directions (Figure 3). As mean normalized expression values decrease, expression changes must increase for transcripts to be significant. The same relationship for significance is demonstrated in all comparisons between treatment groups (Figure S5).

Figure 3. Relationship between mean expression and log2 FC in the AFB to CNTL comparison.

Log2 fold change (FC) was plotted against the mean normalized read counts for each predicted transcript with non-zero expression values in both the control (CNTL) and aflatoxin B1 (AFB) treatments. As determined in DESeq [27], transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-values ≤0.05) are highlighted in red.

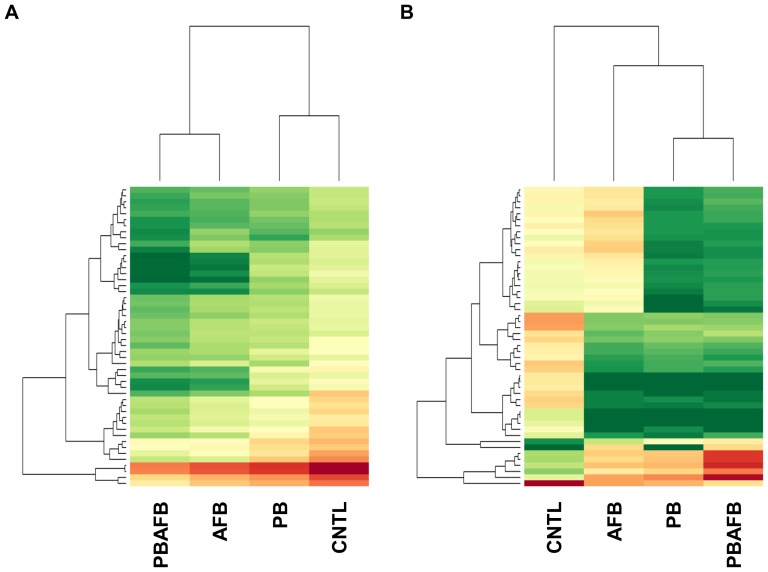

Relative similarity between the four treatments depends on the transcripts selected for comparison. When the 50 transcripts with highest expression levels are compared, the treatments divide into two clusters (CNTL and PB, and AFB and PBAFB) with highest expression values in the CNTL (Figure 4A). When comparing expression of the 50 transcripts with the greatest significant DE, the PB and PBAFB groups cluster (Figure 4B). Expression in the AFB group shares similarities with both this cluster and the CNTL group. Beyond these overall trends, each pair-wise comparison also illustrates specific effects of AFB1 and probiotic treatments on expression.

Figure 4. Comparative expression of select transcripts across four treatment groups.

Heat maps were generated from variance stabilized and normalized read counts using DESeq [27] across the control (CNTL), aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups. Expression level for each transcript is represented by a color range from green (low expression) to red (high expression). (A) 50 transcripts with the highest expression across all treatments. (B) 50 transcripts with the most highly significant differential expression (DE) in pair-wise comparisons to the CNTL.

AFB versus CNTL

Comparison of expression in the AFB and CNTL groups identified 144,403 shared transcripts after threshold filtering (Figure 1). Expression of 313 predicted transcripts was significantly affected by AFB1 treatment (Figure 2A); this is a greater number of significant DE transcripts than observed in any other treatment group (PB or PBAFB, see below). In the AFB group, 60.4% of significant DE transcripts were up-regulated (Figure 2A; Figure 5A), with large log2 fold changes seen in transcripts from keratin 20 (KRT20), cell-death activator CIDE-3 (CIDEC), and E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm2 (MDM2). DE was most significant for transcripts from S-adenosylmethionine synthase isoform type-2 (MAT2A) and A2M (q-value = 3.22E-11). BLAST identified genes corresponding to 50.5% of transcripts with significant DE in the AFB group (Table S3). When expanded to include all sequences in the NR database, annotation increased to 88.8%, primarily due to hits to uncharacterized cDNAs.

Figure 5. Magnitude of expression changes in transcripts with significant DE in each comparison between treatments.

The number of significantly up- or down-regulated transcripts in each range of log2 fold change (FC) is illustrated for each pair-wise comparison. (A) Transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) in the aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB) and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups compared to the control (CNTL) group. (B) Transcripts with significant DE in PBAFB compared to AFB and PB.

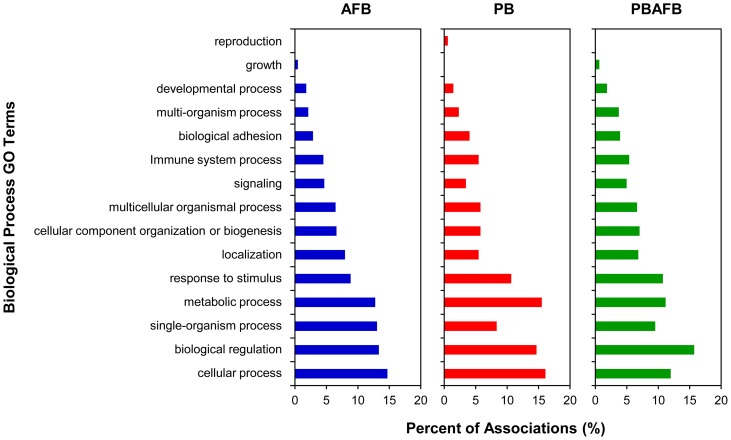

Associations to level 2 Biological Process GO terms were made for 132 significant DE transcripts (42.2%) (Table S3). Cellular process, single-organism process and biological regulation were the most often associated GO terms (Figure 6). As a parent term for apoptotic GO terms, “single-organism process” occurred more frequently in the AFB group (13.0%) than in any other treatment. Many (21.4%) significant DE transcripts have homology to genes with known function in carcinogenesis or apoptosis. The most significant of these transcripts are shown in Table 3. Other transcripts with significant DE in the AFB group had homology with genes involved in lipid metabolism or accumulation. For example, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and MID1 interacting protein 1 (MID1IP1) were significantly down-regulated only in the AFB group (Table 4).

Figure 6. Biological process GO terms associated with significant DE transcripts in treatments compared to CNTL.

For each pair-wise comparison to the control (CNTL) group, level 2 biological process Gene Ontology (GO) terms were matched to transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) using BLAST2GO [32]. The distribution of associated GO terms for significant transcripts in the aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups was plotted as the percent of total associations.

Table 3. Transcripts involved in carcinogenesis and/or apoptosis with significant DE in treatment comparisons to CNTL.

| AFB | PB | PBAFB | ||||||

| Transcript ID | BLAST Hit Name1 | Symbol | Log2 FC | q-value | Log2 FC | q-value | Log2 FC | q-value |

| Locus_921_Transcript_5 | alpha-2-macroglobulin2 | A2M | −9.40 | 3.22E–11 | −10.10 | 1.05E–21 | −8.34 | 2.45E–06 |

| Locus_921_Transcript_6 | alpha-2-macroglobulin2 | A2M | −9.47 | 3.22E–11 | −8.17 | 5.07E–20 | −10.41 | 2.56E–07 |

| Locus_5_Transcript_11597 | aldolase B, fructose-bisphosphate2 | ALDOB | −2.66 | 0.0418 | −3.04 | 1.28E–05 | −5.10 | 0.00266 |

| Locus_1135_Transcript_8 | aldolase B, fructose-bisphosphate2 | ALDOB | −3.15 | 0.00365 | −0.14 | 1.00 | −2.18 | 1.00 |

| Locus_66538_Transcript_2 | BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 4 | BAG4 | 3.11 | 1.00 | 3.54 | 0.322 | 6.99 | 9.02E–05 |

| Locus_66856_Transcript_6 | cell-death activator CIDE-32 | CIDEC | 3.81 | 0.0027 | 2.91 | 0.0233 | 5.21 | 0.00327 |

| Locus_212_Transcript_13 | CDK inhibitor CIP12 | CIP1 | 5.47 | 7.85E–07 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 6.23 | 1.78E–04 |

| Locus_158_Transcript_290 | ceruloplasmin2 | CP | 3.12 | 0.0418 | −0.30 | 1.00 | 1.99 | 1.00 |

| Locus_7438_Transcript_1 | cathepsin E | CTSE | −3.11 | 0.0238 | −0.91 | 1.00 | −4.90 | 0.0133 |

| Locus_11901_Transcript_17 | deiodinase, iodothyronine, type II2 | DIO2 | −1.62 | 1.00 | −1.43 | 1.00 | −4.84 | 0.0106 |

| Locus_55440_Transcript_3 | deleted in malignant brain tumors 12 | DMBT1 | INF | 0.417 | INF | 1.00 | INF | 0.00773 |

| Locus_53943_Transcript_1 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase isoform type-2 | MAT2A | INF | 3.22E–11 | NE | N/A | INF | 1.69E–06 |

| Locus_196_Transcript_166 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm22 | MDM2 | 4.24 | 7.68E–05 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 4.49 | 0.0161 |

| Locus_3434_Transcript_9 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm22 | MDM2 | 6.30 | 0.0114 | 1.41 | 1.00 | 7.67 | 0.00188 |

| Locus_3773_Transcript_3 | osteopontin2 | OPN | 3.61 | 0.00353 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 3.30 | 0.516 |

| Locus_121_Transcript_17 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha2 | PIK3CA | −3.81 | 4.49E–04 | 1.70 | 0.233 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| Locus_12205_Transcript_1 | TAK1-like protein | TAK1L | 4.81 | 0.00187 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 3.75 | 1.00 |

Putative functions were identified for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-value ≤0.05) using IPA, BLAST2GO or through primary literature. Log2 fold change (FC) and q-values were determined for transcripts in the aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups compared to the control (CNTL) group using DESeq [27]. Non-significant transcripts (q-value >0.05) are shown in grey.

See Table S3 for complete BLAST annotation for these transcripts.

Multiple transcripts had significant DE for these genes; only most significant for each pair-wise comparison is shown.

Table 4. Transcripts involved in steatosis or lipid metabolism with significant DE in treatment comparisons to CNTL.

| AFB | PB | PBAFB | ||||||

| Transcript ID | BLAST Hit Name1 | Symbol | Log2 FC | q-value | Log2 FC | q-value | Log2 FC | q-value |

| Locus_108_Transcript_6 | apolipoprotein A-IV2 | APOA4 | 3.98 | 9.93E–05 | 2.80 | 2.44E–04 | 5.40 | 7.63E–04 |

| Locus_108_Transcript_13 | apolipoprotein A-IV2 | APOA4 | 3.63 | 0.0023 | 4.20 | 6.39E–09 | 6.72 | 1.40E–05 |

| Locus_5_Transcript_12840 | glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic subunit2 | G6PC* | 3.74 | 2.99E–04 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Locus_5083_Transcript_14 | lipoprotein lipase2 | LPL | −2.85 | 0.0409 | 0.21 | 1.00 | −2.00 | 1.00 |

| Locus_17578_Transcript_1 | MID1 interacting protein 1 | MID1IP1 | −4.04 | 8.95E–05 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 2.56 | 1.00 |

| Locus_54740_Transcript_1 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | PCK1 | 3.64 | 0.00478 | 4.39 | 7.86E–09 | 6.12 | 1.31E–04 |

Putative functions were identified for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-value ≤0.05) using IPA, BLAST2GO or primary literature. Log2 fold change (FC) and q-values were determined for transcripts in the aflatoxin B1 (AFB), probiotic mixture (PB), and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) groups compared to the control (CNTL) group using DESeq [27]. Non-significant transcripts (q-value >0.05) are shown in grey.

See Table S3 for complete BLAST annotation for these transcripts.

Multiple transcripts had significant DE for these genes; only most significant for each pair-wise comparison is shown.

Although the liver is the site of AFB1 bioprocessing, none of the transcripts associated with CYP and GSTA genes had significant DE in the AFB group. Almost no change in expression was observed for transcripts from CYP1A5 and CYP3A37, which encode the two liver P450s that activate AFB1 [11] (average log2 fold changes of −0.01 and −0.16). Expression changes were also minimal for five of the six GSTA genes (averages of 0.16, 0.25, 0.24, 1.38, and 0.39 for GSTA1.1, GSTA1.2, GSTA2, GSTA3, and GSTA4). No transcripts matched to the GSTA1.3 gene in any treatment group.

PB versus CNTL

The PB and CNTL groups share the fewest number of filtered transcripts (143,890) (Figure 1), yet only 206 significant DE transcripts were identified in the PB treatment group (Figure 2A). BLAST annotated 46.6% (58.3% with NR sequences) of these transcripts (Table S3). Unlike the AFB group, significant DE transcripts in the PB group are predominantly down-regulated (Figure 2A; Figure 5A), leading to a significantly lower mean log2 fold change than in the AFB1-treated groups (AFB or PBAFB, Figure S6A). Some down-regulated transcripts, including many from A2M, had higher significance (smaller q-values) than any transcripts in the AFB1-treated groups (Figure S7A, B, C).

Associations were made between 41.3% of these significant DE transcripts and Biological Process GO terms (Table S3). The most frequently associated level 2 terms were cellular process, metabolic process, and biological regulation (Figure 6). Transcripts from CYP2H1 and poly(U)-specific endoribonuclease-A-like (ENDOU) were significantly down-regulated in the PB group (Table S3), illustrating the impact of probiotics on metabolic and enzymatic functions. Unlike the AFB1-treated groups (AFB and PBAFB), only 9.7% of significant transcripts in PB had links to cancer and these were almost exclusively transcripts from A2M. Since these transcripts were significantly down-regulated in all three treatment groups (Table 3), A2M is unlikely to be involved in AFB1 toxicity.

PBAFB versus CNTL

A total of 145,708 filtered transcripts were shared between the PBAFB and CNTL groups (Figure 1), exceeding those found for both the AFB and PB groups. Only 208 predicted transcripts had significant DE in the PBAFB group (Figure 2A) and BLAST successfully identified 66.8% (80.3% with NR sequences) of these transcripts (Table S3). More than half (51.4%) were shared with the AFB group, but only 34.1% were significantly DE in both PBAFB and PB (Figure 2A). Similar to the AFB group, the majority (57.2%) of transcripts with significant DE were up-regulated (Figure 2A; Figure 5A). Larger changes in expression were required for significant DE in the PBAFB group, than in either AFB or PB (Figure 5A). Transcripts with significant DE in the PBAFB group more closely resembled those of the AFB group, indicating an AFB1 treatment effect.

Functional analysis found GO term associations for 42.3% of significant DE transcripts (Table S3) and identified further similarities between PBAFB and the other treatment groups. As in the PB group, biological regulation, metabolic process, and cellular process were the most commonly associated level 2 GO terms in the PBAFB group (Figure 6). Localization, single-organism process, and to a lesser extent signaling and cellular component organization or biogenesis GO terms occurred at higher proportions in the AFB and PBAFB groups. Increased GO associations with the “multi-organism process” term were observed in only the PBAFB group. Including transcripts from MAT2A and MDM2, 27.8% of significant DE transcripts in PBAFB were annotated to genes with known roles in cancer or apoptosis. Greater up-regulation was observed in the PBAFB group than in the AFB group for many significant transcripts involved in carcinogenesis or lipid regulation (CIDEC, CDK inhibitor CIP1 (CIP1), MDM2, Table 3; APOA4, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1), Table 4).

Inter-treatment Comparisons

Additional inter-treatment comparisons (PBAFB vs. AFB and PBAFB vs. PB) identified 565 transcripts with significant DE (Table S3). Most (353) of the 448 transcripts with significant DE in PBAFB vs. PB were up-regulated (Figure 2B; Figure 5B). Highly up-regulated transcripts from MAT2A, CIP1, and MDM2 also had some of the highest significance values. Nearly 60% of significant DE transcripts in the PBAFB group compared to the AFB group were also up-regulated, but the transcripts with the highest significance were down-regulated and could not be BLAST annotated (Figure S7D). Comparison of the AFB1-treated groups (PBAFB vs. AFB) also found larger decreases in expression than observed in PBAFB vs. PB (Figure 5B, Figure S6B). Gene expression in the PBAFB group more closely resembled the AFB group, with 152,132 shared transcripts. A smaller number of transcripts (151,010) were shared between the PBAFB and PB groups. Together these suggest that the combined treatment (PBAFB) is more similar to treatment with AFB1 than probiotics.

Exposure to AFB1 (AFB and PBAFB groups) initiated expression of cancer-associated transcripts (such as MAT2A) not observed in the CNTL or PB groups. Fourteen transcripts, including expressed sequences from collagen, type II, alpha 1 (COL2A1) and BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 4 (BAG4), were significantly up-regulated in PBAFB in comparisons to both AFB and to PB indicating a synergistic effect. “Metabolic process” was most commonly associated GO term for significant DE transcripts in the PBAFB verses AFB comparison (Figure S8). For example, a transcript from CYP51A1 was significantly up-regulated in the PBAFB group compared to the AFB group (Table S3). A higher proportion of associations to the GO terms developmental process, multicellular organismal process, and response to stimulus was identified when comparing AFB1-treated groups (PBAFB vs. AFB) than probiotic-treated (PBAFB vs. PB). When comparing the probiotic treated groups, the GO terms biological regulation, cellular component organization or biogenesis, localization, and signaling occurred more frequently, illustrating the impact of AFB1 exposure on apoptotic, cell cycle and other regulatory genes. Further investigation of the hepatic functions and pathways of these significant transcripts in the domestic turkey will be necessary to determine molecular mechanism by which AFB1 initiates carcinogenesis and lipid misregulation in poultry.

Discussion

Along with providing a first characterization of the turkey liver transcriptome, this study identified several genes potentially affected by exposure to AFB1 and probiotics. Despite their known role in AFBO production [11], expression of CYP1A5 and CYP3A37 did not change in the AFB1-treated groups. However, probiotics influenced expression of transcripts from other CYP gene family members. AFB1 exposure also had no significant impact on expression of GSTA genes. Domestic turkey hepatic GSTAs are unable to conjugate AFBO in vivo, yet these enzymes have activity when heterologously expressed in E. coli [9], [10]. Hence, gene silencing mechanisms or post-transcriptional modifications are likely responsible for this dysfunction [9], either of which is consistent with the absence of significant DE in GSTA transcripts. Invariable expression in these CYP and GSTA genes means that the transcriptional response to AFB1 is mediated through genes not previously linked to aflatoxicosis in the domestic turkey.

Changes in transcript abundance were quantified through RNA-seq and novel genes in the liver transcriptome were associated with exposure to AFB1 and/or probiotics. Functional analysis of the significantly affected transcripts identified three major impacts: effects of AFB1 on genes linked to cancer, effects of AFB1 on genes involved in lipid metabolism, and opposing effects of PB and the combined PBAFB treatment.

AFB1 and Cancer

The carcinogenic nature of AFB1 in mammals is well established and chronic exposure is an established risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in humans [2], [8]. In poultry, both acute and chronic AFB1 consumption cause lesions in the liver, including necrotic hepatocellular loci, focal hemorrhages, and fatty vacuolation of hepatocytes [5], [6], [34], [35]. Dietary AFB1 is also mutagenic in chickens, turkeys and other poultry, first generating biliary hyperplasia, followed by fibrosis and nodular tissue regeneration during long-term exposure [5], [6], [34], [35]. Histological analysis on liver sections from the AFB group identified, on average, 5–30% necrotic hepatocytes and moderate biliary hyperplasia [18]. Adverse effects on the liver from AFB1 exposure are likely driven by genes associated with the cycle cell and apoptosis.

Differential expression analysis of the turkey liver transcriptome identified a large number of transcripts derived from genes with known links to liver cancer in mammals. The strongest down-regulation was observed in transcripts from A2M, which encodes a proteinase inhibitor. A2M has been associated with human and rat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but reports conflict on whether its expression is up- or down-regulated [36], [37], [38]. AFB1 has also been shown to decrease A2M secretion from rat hepatocytes [39]. However, it is unlikely that A2M is a driver of AFB1 toxicity in the turkey, since A2M transcripts were down-regulated in all three treatments, including the PB group.

Most transcripts with significant DE in the AFB group were up-regulated. Large increases in expression were observed for MDM2, which encodes an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that acts on p53, causing its degradation by the proteosome. In human lung cells expressing P450s, AFB1 has been shown to cause a concentration-dependent increase in MDM2 expression [40]. Overexpression and polymorphisms in MDM2 have been linked to human HCC [41], [42], [43]. Up-regulation of MDM2 was also observed in response to AFB1 exposure in swine [19] and this may be a conserved response to AFB1 exposure across diverse species, including poultry. Misregulation of MDM2 could play a role in hyperplasia and other liver remodeling processes by over-inhibiting tumor suppressors and apoptotic pathways and decreasing control of the cell cycle.

Another gene up-regulated in hepatic responses to AFB1 was osteopontin (OPN), which encodes an extracellular matrix glycoprotein produced by both immune cells and tumor cells. In mammalian liver, OPN acts as a signaling molecule and has been linked to inflammation, leukocyte infiltration, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis [44], [45]. Unlike the turkey, OPN expression was down-regulated in the chicken liver after AFB1 exposure [13]. This difference may be a result of the increased sensitivity of turkeys to AFB1 toxicity [3], [5]. AFB1 can also turn on expression of genes not found in untreated birds (i.e. the CNTL group). MAT2A was expressed only in the AFB and PBAFB treatment groups. In humans, two genes, MAT1A and MAT2A, encode interchangeable synthase subunits that produce S-adenosylmethionine, which is involved in hepatocyte growth and apoptosis [46]. In normal mammalian hepatocytes, only MAT1A is expressed, while development of HCC turns on MAT2A expression in place of MAT1A. MAT1A has been shown to be down-regulated after AFB1 consumption in pigs [19]. Up-regulation of MDM2, OPN and MAT2A in the turkey appears to participate in the proliferative phenotype in the liver after AFB1 exposure.

AFB1 and Lipids

AFB1 exposure also changes lipid metabolism and causes steatosis in the liver. In turkeys and chickens, increased lipid content often causes liver pigmentation to become pale or yellowed [5], [35], [47]. This change arises from an increase in lipid-containing vacuoles in hepatocytes [5], [6], [35]. Pale livers were observed in turkeys from the AFB group [18] and significant DE was identified for multiple genes involved in lipid regulation. LPL and MID1IP1 were significantly down-regulated only in the AFB group. A similar decrease in LPL expression was observed in the liver of chickens exposed to AFB1 [13]. As a lipase, LPL is involved in the breakdown of triglycerides in lipoproteins and essential to lipid metabolism and storage. High hepatic LPL activity and mRNA expression have been linked to liver steatosis in humans and mice [48], [49]. Lower plasma LPL activity and increased hepatic expression have also been correlated with higher lipid storage in livers from certain breeds of geese [50], [51]. AFB1 has an opposite effect on LPL expression, but still induces fatty change in hepatocytes. AFB1 impacts on LPL activity in the liver and periphery and the mechanism of lipid accumulation in the liver need to be elucidated. In mammals, MID1IP1 is a regulator of lipogenesis that turns on fatty acid synthesis through activation of acetyl-coA carboxylase [52], [53]. Down-regulation of this lipogenic protein in the turkey could be a hepatic response to the increased retention of lipids in the liver.

Impact of Probiotics

Previous research has identified many beneficial probiotics useful as feed additives in poultry, including strains of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria and Propionibacteria [54], [55], [56]. In this challenge study, probiotic treatment significantly decreased expression of many transcripts. Reduced expression of genes involved in metabolic processes, such as A2M, ENDOU, and serine racemase (SRR), could limit the biosynthetic capabilities of the liver. Examining the liver transcriptome of the PBAFB group allows for evaluation of the efficacy of the PB treatment in reducing aflatoxicosis. PBAFB treatment decreased the number of transcripts with significant DE compared to AFB1 treatment alone and led to normal liver weights and weight gains [18]. However, the levels of hepatocyte necrosis and biliary hyperplasia were not reduced [18]. Most transcripts with significant DE in both the AFB and PBAFB groups had a higher log2 fold change in the PBAFB group, suggesting a synergistic effect. Additionally, approximately 70 transcripts had significant DE only in the PBAFB group, further suggesting an interaction between these treatments. Therefore, the addition of PB does modulate the effects of AFB1, but expression levels for many transcripts do not resemble the CNTL group. Although full mitigation of AFB1 toxicity was not expected, treatment with probiotics was not as protective as might be predicted. Further experiments would be needed to determine if higher concentrations or different compositions of dietary probiotics can reduce hepatic lesions and gene expression changes caused by AFB1.

Conclusions

General characterization of liver transcriptome dynamics in response to toxicological challenge with AFB1 was achieved by RNA-seq in the turkey. Transcriptome analysis identified genes involved in responses to AFB1, genes that were misregulated as a result of toxicity, and genes modulated by the probiotics. These genes provide a list of targets for further investigation of AFB1 toxicity in the turkey liver. MDM2, OPN and other genes linked to cancer provide evidence for the apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory pathways that are likely the molecular mechanisms of inflammation, proliferation and liver damage in aflatoxicosis. Further investigation of these pathways at the cellular level would be beneficial to both basic understanding of aflatoxicosis and applications to reduce toxic processes. Regulatory and signaling genes like OPN could be useful for direct modulation of responses to toxicity. Genes such as LPL, MAT2A, and MDM2 could be utilized as biomarkers for AFB1 exposure and aflatoxicosis in flocks and in efficacy testing for potential toxicity reduction strategies.

Investigating aflatoxicosis through transcriptome sequencing provides a powerful approach for research aiming to reduce poultry susceptibility to AFB1. In this context, RNA-seq would be an effective tool for future toxicity studies. By examining the transcriptomes of the spleen, kidney, muscle and other tissues, the systemic effects of AFB1 exposure could be further elucidated. Comparative analysis of other galliform species could also distinguish differences in AFB1 response, beyond the known variation in liver bioprocessing [57], [58]. Characterizing variation in transcriptome responses to AFB1 and to other mycotoxins and dietary contaminants could allow for the identification of protective alleles with the potential to mitigate the effects of aflatoxicosis.

Supporting Information

Average quality scores per read for RNA-seq datasets after filtering and trimming. Quality scores were averaged and the number of reads totaled by score with FastQC [22]. Quality scores were plotted against read counts for the cumulative liver data (black), as well as each treatment dataset. The control (CNTL) (green) and aflatoxin B1 (AFB) (blue) samples were run on flow cell 1, while the probiotic mixture (PB) (red) and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) (purple) were run on flow cell 2.

(TIF)

Quality scores at each base position for RNA-seq datasets after filtering and trimming. Box-plots were generated using FastQC [22]. The red line represents the median and the blue line the mean at each base. (A) Control (CNTL). (B) Aflatoxin B1 (AFB). (C) Probiotic mixture (PB). (D) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB).

(TIF)

Depth of coverage on predicted transcripts for each treatment group. The number of transcripts was plotted for each level of read coverage for the control (CNTL) (green), aflatoxin B1 (AFB) (blue), probiotic (PB) (red) and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) (purple) groups. A threshold of 0.1 read/million mapped was used to filter transcripts for coverage. The minimum read depth to meet this threshold varied most between treatments on flow cell 1 (long dash) and flow cell 2 (short dash) due to different library sizes.

(TIF)

Histogram of de novo assembled transcript lengths after coverage threshold filtering. Each bin represents the number of filtered transcripts with a length less than or equal to the bin value, but greater than the previous bin.

(TIF)

Pair-wise comparisons of mean expression and log2 FC between treatments. Each plot shows log2 fold change (FC) against mean normalized expression for predicted transcripts with non-zero expression values in both treatments generated in DESeq [27]. Transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-values ≤0.05) are highlighted in red. (A). Probiotic mixture (PB) to control (CNTL). (B) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) to CNTL. (C) PBAFB to aflatoxin B1 (AFB). (D) PBAFB to PB.

(TIF)

Box-plots of log2 FC for transcripts with significant DE in each pair-wise comparison. Each plot shows the distribution of log2 fold change (FC) for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q- value ≤0.05) between treatments and with non-zero normalized expression values in both treatments. Treatments with significantly different mean log2 FC (p-value ≤0.05) are indicated by an *. Outliers are illustrated by open circles. (A) Log2 FC for significant transcripts in each treatment compared to the control (CNTL). (B) Log2 FC for significant transcripts in the probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) group compared to the aflatoxin B1 (AFB) or probiotic mixture (PB) group.

(TIF)

Relationship between log2 FC and significance level for each pair-wise comparison. Each volcano plot shows –log10 p-value against log2 fold change (FC) for predicted transcripts expressed in both treatments. Transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-value ≤0.05) are highlighted in red. (A) Aflatoxin B1 (AFB) to control (CNTL). (B) Probiotic mixture (PB) to CNTL. (C) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) to CNTL. (D) PBAFB to AFB. (E) PBAFB to PB.

(TIF)

Biological process GO terms associated with significant DE transcripts in PBAFB inter-treatment comparisons. Using BLAST2GO [32], level 2 biological process Gene Ontology (GO) terms were identified for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) in the probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) group when compared to the aflatoxin B1 (AFB) or probiotic mixture (PB) group. The distribution of associated GO terms for these significant transcripts was plotted as the percent of total associations.

(TIF)

Results of filtering predicted liver transcripts by a coverage threshold (0.1 read/million).

(DOCX)

Distribution of filtered transcripts across the turkey genome (build UMD 2.01).

(DOCX)

Characterization of predicted transcripts with significant DE identified using DESeq. Results of differential expression (DE) analysis in DESeq [27] were compiled with read counts from HTSeq [26], BLAST annotations, and Gene Ontology (GO) terms from BLAST2GO [32]. Each tab represents a pair-wise comparison between treatment groups. Raw and normalized expression values, fold change (FC), log2 FC, p-values, q-values (FDR-adjusted p-values), top BLAST hits for the turkey, chicken, Swiss-Prot and non-redundant (NR) databases, and GO terms are shown for each significant transcript.

(XLSX)

ARRIVE Checklist.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Moroni Feed Co (Ephraim, UT) for supplying the turkeys and feed and Bruce Eckloff (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for preparation and sequencing of the RNA libraries. The authors also thank our collaborator Rami A. Dalloul (Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA) for facilitating the relationship between the UMN and VBI.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by USDA-AFRI Grants #2007-35205-17880, 2009-35205-05302 and 2013-01043 from the USDA NIFA Animal Genome Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.CAST (1989) Mycotoxins: Economic and health risks. Ames: Council for Agricultural Science and Technology. 99 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coulombe RA Jr (1993) Biological action of mycotoxins. J Dairy Sci 76: 880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rawal S, Kim JE, Coulombe Jr R (2010) Aflatoxin B1 in poultry: Toxicology, metabolism and prevention. Res Vet Sci 89: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blount WP (1961) Turkey “X” disease.Turkeys 9 : 52, 55–58, 61–71, 77. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giambrone JJ, Diener UL, Davis ND, Panangala VS, Hoerr FJ (1985) Effects of aflatoxin on young turkeys and broiler chickens. Poult Sci 64: 1678–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pandey I, Chauhan SS (2007) Studies on production performance and toxin residues in tissues and eggs of layer chickens fed on diets with various concentrations of aflatoxin AFB1. Br Poult Sci 48: 713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qureshi MA, Brake J, Hamilton PB, Hagler Jr WM, Nesheim S (1998) Dietary exposure of broiler breeders to aflatoxin results in immune dysfunction in progeny chicks. Poult Sci 77: 812–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eaton DL, Gallagher EP (1994) Mechanism of aflatoxin carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 34: 135–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim JE, Bunderson BR, Croasdell A, Coulombe Jr RA (2011) Functional characterization of alpha-class glutathione S-transferases from the turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Toxicol Sci 124: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klein PJ, Buckner R, Kelly J, Coulombe Jr RA (2000) Biochemical basis for the extreme sensitivity of turkeys to aflatoxin B(1). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 165: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rawal S, Coulombe Jr RA (2011) Metabolism of aflatoxin B1 in turkey liver microsomes: the relative roles of cytochromes P450 1A5 and 3A37. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 254: 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corrier DE (1991) Mycotoxicosis: Mechanisms of immunosuppression. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 30: 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yarru LP, Settivari RS, Antoniou E, Ledoux DR, Rottinghaus GE (2009) Toxicological and gene expression analysis of the impact of aflatoxin B1 on hepatic function of male broiler chicks. Poult Sci 88: 360–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El-Nezami H, Kankaanpää P, Salminen S, Ahokas J (1998) Ability of dairy strains of lactic acid bacteria to bind a common food carcinogen, aflatoxin B1 . Food Chem Toxicol 36: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gratz S, Mykkanen H, El-Nezami H (2005) Aflatoxin B1 binding by a mixture of Lactobacillus and Propionibacterium: In vitro versus ex vivo . J Food Prot 68: 2470–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oatley JT, Rarick MD, Ji GE, Linz JE (2000) Binding of aflatoxin B1 to Bifidobacteria in vitro. J Food Prot 63: 1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Nezami H, Mykkanen H, Kankaanpaa P, Salminen S, Ahokas J (2000) Ability of Lactobacillus and Propionibacterium strains to remove aflatoxin B1 from the chicken duodenum. J Food Prot 63: 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawal S, Bauer MM, Mendoza KM, El-Nezami H, Hall JR, et al. (2014) Aflatoxicosis chemoprevention by probiotic Lactobacillius and its impact on BG genes of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Res Vet Sci in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Rustemeyer SM, Lamberson WR, Ledoux DR, Wells K, Austin KJ, et al. (2005) Effects of dietary aflatoxin on the hepatic expression of apoptosis genes in growing barrows. J Anim Sci 89: 916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klein PJ, Van Vleet TR, Hall JO, Coulombe Jr RA (2002) Biochemical factors underlying the age-related sensitivity of turkeys to aflatoxin B(1). Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 132: 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gratz S, Täubel M, Juvonen RO, Viluksela M, Turner PC, et al. (2006) Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG modulates intestinal absorption, fecal excretion and toxicity of aflatoxin B1 in rats. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 7398–7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrews S (2010) FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed 2011 October 6.

- 23. Zerbino DR, Birney E (2008) Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 18: 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E (2012) Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics 28: 1086–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anders S (2010) HTSeq: Analysing high-throughput sequencing data with Python. Available: http://www-huber.embl.de/users/anders/HTSeq/. Accessed 2011 September.

- 27. Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hulsen T, de Vlieg J, Alkema W (2008) BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics 9: 488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveros JC (2007) VENNY: An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn Diagrams. Available: http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/. Accessed 2013 August 14.

- 30. Chen H, Boutros PC (2011) VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics. 12: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu TD, Watanabe CK (2005) GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics 21: 1859–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Conesa A, Götz S, Garcia-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talon M, et al. (2005) Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21: 3674–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Götz S, Garcia-Gómez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, et al. (2008) High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 3420–3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klein PJ, Van Vleet TR, Hall JO, Coulombe Jr RA (2002) Dietary butylated hydroxytoluene protects against aflatoxicosis in turkeys. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 182: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Newberne PM, Butler WH (1969) Acute and chronic effects of aflatoxin on the liver of domestic and laboratory animals: a review. Cancer Res 29: 236–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lau WY, Lai PB, Leung MF, Leung BC, Wong N, et al. (2000) Differential gene expression of hepatocellular carcinoma using cDNA microarray analysis. Oncol Res 12: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ho AS, Cheng CC, Lee SC, Liu ML, Lee JY, et al. (2010) Novel biomarkers predict liver fibrosis in hepatitis C patients: alpha 2 macroglobulin, vitamin D binding protein and apolipoprotein AI. J Biomedical Sci 17: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smorenburg SM, Griffini P, Tiggelman AB, Moorman AF, Boers W, et al. (1996) α2-macroglobulin is mainly produced by cancer cells and not by hepatocytes in rats with colon carcinoma metastases in liver. Hepatology 23: 560–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farkas D, Bhat VB, Mandapati S, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR (2005) Characterization of the secreted proteome of rat hepatocytes cultured in collagen sandwiches. Chem Res Toxicol 18: 1132–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Vleet TR, Watterson TL, Klein PJ, Coulombe Jr RA (2006) Aflatoxin B1 alters the expression of p53 in cytochrome P450-expressing human lung cells. Toxicol Sci 89: 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Endo K, Ueda T, Ohta T, Terada T (2000) Protein expression of MDM2 and its clinicopathological relationships in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver 20: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schlott T, Ahrens K, Ruschenburg I, Reimer S, Hartmann H, et al. (1999) Different gene expression of MDM2, GAGE-1, -2, and FHIT in hepatocellular carcinoma and focal nodular hyperplasia. Br J Cancer 80: 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoon YJ, Chang HY, Ahn SH, Kim JK, Park YK, et al. (2008) MDM2 and p53 polymorphisms are associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Carcinogenesis 29: 1192–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nagoshi S (2014) Osteopontin: Versatile modulator of liver diseases. Hepatol Res 44: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramajah SK, Rittling S (2008) Pathophysiological role of osteopontin in hepatic inflammation, toxicity and cancer. Toxicol Sci 103: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu SC, Mato JM (2008) S-Adenosylmethionine in cell growth, apoptosis and liver cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23: S73–S77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sims Jr WM, Kelley DC, Sanford PE (1970) A study of aflatoxicosis in laying hens. Poult Sci 49: 1082–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ahn J, Lee H, Chung CH, Ha T (2011) High fat diet induced downregulation of microRNA-467b increased lipoprotein lipase in hepatic steatosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414: 664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pardina E, Baena-Fustegueras JA, Llamas R, Catalán R, Galard R, et al. (2009) Lipoprotein lipase expression in livers of morbidly obese patients could be responsible for liver steatosis. Obes Surg 19: 608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chunchun H, Jiwen W, Hengyong X, Liang L, Jianqiang Y, et al. (2008) Effect of overfeeding on plasma parameters and mRNA expression of genes associated with hepatic lipogenesis in geese. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci 21: 590–595. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davail S, Guy G, André J, Hermier D, Hoo-Paris R (2000) Metabolism in two breeds of geese with moderate or large overfeeding induced liver-steatosis. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 126: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Inoue J, Yamasaki K, Ikeuchi E, Satoh S, Fujiwara Y, et al. (2011) Identification of MIG12 as a mediator for simulation of lipogenesis by LXR activation. Mol Endocrinol 25: 995–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim CW, Moon YA, Park SW, Cheng D, Kwon HJ, et al. (2010) Induced polymerization of mammalian acetyl-CoA carboxylase by MIG12 provides a tertiary level of regulation of fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 9626–9631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luo J, King S, Adams MC (2010) Effect of probiotic Propionibacterium jensenii 702 supplementation on layer chicken performance. Benef Microbes 1: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mountzouris KC, Tsirtsikos P, Kalamara E, Nitsch S, Schatzmayr G, et al. (2007) Evaluation of the efficacy of a probiotic containing Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Pediococcus strains in promoting broiler performance and modulating cecal microflora composition and metabolic activities. Poult Sci 86: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salim HM, Kang HK, Akter N, Kim DW, Kim JH, et al. (2013) Supplementation of direct-fed microbials as an alternative to antibiotic on growth performance, immune responses, cecal microbial population, and ileal morphology of broiler chickens. Poult Sci 92: 2084–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lozano MC, Diaz GJ (2006) Microsomal and cytosolic biotransformation of aflatoxin B1 in four poultry species. Br Poult Sci 47: 734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Murcia HW, Díaz GJ, Cepeda SM (2011) Enzymatic activity in turkey, duck, quail and chicken liver microsomes against four human cytochrome P450 prototype substrates and aflatoxin B1. J Xenobiotics 1: e4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Average quality scores per read for RNA-seq datasets after filtering and trimming. Quality scores were averaged and the number of reads totaled by score with FastQC [22]. Quality scores were plotted against read counts for the cumulative liver data (black), as well as each treatment dataset. The control (CNTL) (green) and aflatoxin B1 (AFB) (blue) samples were run on flow cell 1, while the probiotic mixture (PB) (red) and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) (purple) were run on flow cell 2.

(TIF)

Quality scores at each base position for RNA-seq datasets after filtering and trimming. Box-plots were generated using FastQC [22]. The red line represents the median and the blue line the mean at each base. (A) Control (CNTL). (B) Aflatoxin B1 (AFB). (C) Probiotic mixture (PB). (D) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB).

(TIF)

Depth of coverage on predicted transcripts for each treatment group. The number of transcripts was plotted for each level of read coverage for the control (CNTL) (green), aflatoxin B1 (AFB) (blue), probiotic (PB) (red) and probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) (purple) groups. A threshold of 0.1 read/million mapped was used to filter transcripts for coverage. The minimum read depth to meet this threshold varied most between treatments on flow cell 1 (long dash) and flow cell 2 (short dash) due to different library sizes.

(TIF)

Histogram of de novo assembled transcript lengths after coverage threshold filtering. Each bin represents the number of filtered transcripts with a length less than or equal to the bin value, but greater than the previous bin.

(TIF)

Pair-wise comparisons of mean expression and log2 FC between treatments. Each plot shows log2 fold change (FC) against mean normalized expression for predicted transcripts with non-zero expression values in both treatments generated in DESeq [27]. Transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-values ≤0.05) are highlighted in red. (A). Probiotic mixture (PB) to control (CNTL). (B) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) to CNTL. (C) PBAFB to aflatoxin B1 (AFB). (D) PBAFB to PB.

(TIF)

Box-plots of log2 FC for transcripts with significant DE in each pair-wise comparison. Each plot shows the distribution of log2 fold change (FC) for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q- value ≤0.05) between treatments and with non-zero normalized expression values in both treatments. Treatments with significantly different mean log2 FC (p-value ≤0.05) are indicated by an *. Outliers are illustrated by open circles. (A) Log2 FC for significant transcripts in each treatment compared to the control (CNTL). (B) Log2 FC for significant transcripts in the probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) group compared to the aflatoxin B1 (AFB) or probiotic mixture (PB) group.

(TIF)

Relationship between log2 FC and significance level for each pair-wise comparison. Each volcano plot shows –log10 p-value against log2 fold change (FC) for predicted transcripts expressed in both treatments. Transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) (q-value ≤0.05) are highlighted in red. (A) Aflatoxin B1 (AFB) to control (CNTL). (B) Probiotic mixture (PB) to CNTL. (C) Probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) to CNTL. (D) PBAFB to AFB. (E) PBAFB to PB.

(TIF)

Biological process GO terms associated with significant DE transcripts in PBAFB inter-treatment comparisons. Using BLAST2GO [32], level 2 biological process Gene Ontology (GO) terms were identified for transcripts with significant differential expression (DE) in the probiotic + aflatoxin B1 (PBAFB) group when compared to the aflatoxin B1 (AFB) or probiotic mixture (PB) group. The distribution of associated GO terms for these significant transcripts was plotted as the percent of total associations.

(TIF)

Results of filtering predicted liver transcripts by a coverage threshold (0.1 read/million).

(DOCX)

Distribution of filtered transcripts across the turkey genome (build UMD 2.01).

(DOCX)

Characterization of predicted transcripts with significant DE identified using DESeq. Results of differential expression (DE) analysis in DESeq [27] were compiled with read counts from HTSeq [26], BLAST annotations, and Gene Ontology (GO) terms from BLAST2GO [32]. Each tab represents a pair-wise comparison between treatment groups. Raw and normalized expression values, fold change (FC), log2 FC, p-values, q-values (FDR-adjusted p-values), top BLAST hits for the turkey, chicken, Swiss-Prot and non-redundant (NR) databases, and GO terms are shown for each significant transcript.

(XLSX)

ARRIVE Checklist.

(DOC)