Abstract

Gene introgression and hybrid barriers have long been a major focus of studies of geographically overlapping species. Two pine species, Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis, are frequently observed growing adjacent to each other, where they overlap in a narrow hybrid zone. As a consequence, these species constitute an ideal system for studying genetic introgression and reproductive barriers between naturally hybridizing, adjacently distributed species. In this study, we sampled 270 pine trees along an elevation gradient in Anhui Province, China and analyzed these samples using EST-SSR markers. The molecular data revealed that direct gene flow between the two species was fairly low, and that the majority of gene introgression was intermediated by backcrossing. On the basis of empirical observation, the on-site distribution of pines was divided into a P. massoniana zone, a hybrid zone, and a P. hwangshanensis zone. STRUCTURE analysis revealed the existence of a distinct species boundary between the two pine species. The genetic boundary of the hybrid zone, on the other hand, was indistinct owing to intensive backcrossing with parental species. Compared with P. massoniana, P. hwangshanensis was found to backcross with the hybrids more intensively, consistent with the observation that morphological and anatomical characteristics of trees in the contact zone were biased towards P. hwangshanensis. The introgression ability of amplified alleles varied across species, with some being completely blocked from interspecific introgression. Our study has provided a living example to help explain the persistence of adjacently distributed species coexisting with their interfertile hybrids.

Introduction

Hybridization, or the crossing of different species, subspecies or ‘races’, profoundly influences species evolution. On the one hand, introgressive hybridization can promote gene flow between species, leading to the generation of new genotype combinations and thereby increasing species diversity and ecological adaptability [1]–[3]. Excessive interspecific hybridization, however, will eventually result in genetic assimilation between species [4], [5]. On the other hand, various intrinsic or extrinsic reproductive barriers that reduce hybrid fitness can be formed through introgressive hybridization, thus contributing to the maintenance of species integrity [6]. A balance between gene flow and hybrid barriers is believed to maintain the hybrid zones [7], [8] that develop when hybridization occurs between species with different environmental adaptations [9]. Environmental heterogeneity can lead to a ‘mosaic’ structure in the hybrid zone [10]–[12], as genotype selection often depends on habitat attributes.

Pinus massoniana Lamb and P. hwangshanensis Hsia are two closely related species [13]. They differ in morphology, cytology and timber anatomical characteristics [14], and also display distinct spatial separation. Pinus hwangshanensis is usually distributed above 1,000 m, whereas P. massoniana is commonly found at elevations below 700 m. An elevation range of 700 to 1,000 m is thus empirically considered to be the contact zone between these two species [15]. Trees in the contact zone possess intermediate morphological characteristics, and were at first erroneously identified as a new species [16]. Later, studies involving anatomical characterization [14], molecular markers [17] and organellar DNA [18] led to their reclassification as introgressive hybrids.

Natural hybridization is commonly observed between different pine species [19]–[21]. Similar to other pine species, pollen of P. hwangshanensis and P. massoniana is wind-dispersed, while their seeds are disseminated by animals [13]. Pinus hwangshanensis and P. massoniana have adjacent distributions, and the two species frequently overlap along a narrow contact zone. Seed plumpness, germination rates and weight per thousand seeds have been found to be significantly lower in trees within the contact zone than elsewhere [22]. A previous study revealed that morphological and anatomical characteristics of trees in the contact zone were biased towards P. hwangshanensis [23]. Contrary to this observation, a RAPD marker study demonstrated that gene flow was more intense from P. massoniana to P. hwangshanensis [17]. To resolve this controversy, we studied genetic introgression in these two species along an elevation gradient in their natural distributional range. In addition, we investigated whether a distinguishable boundary exists between the two species at the molecular level.

Materials and Methods

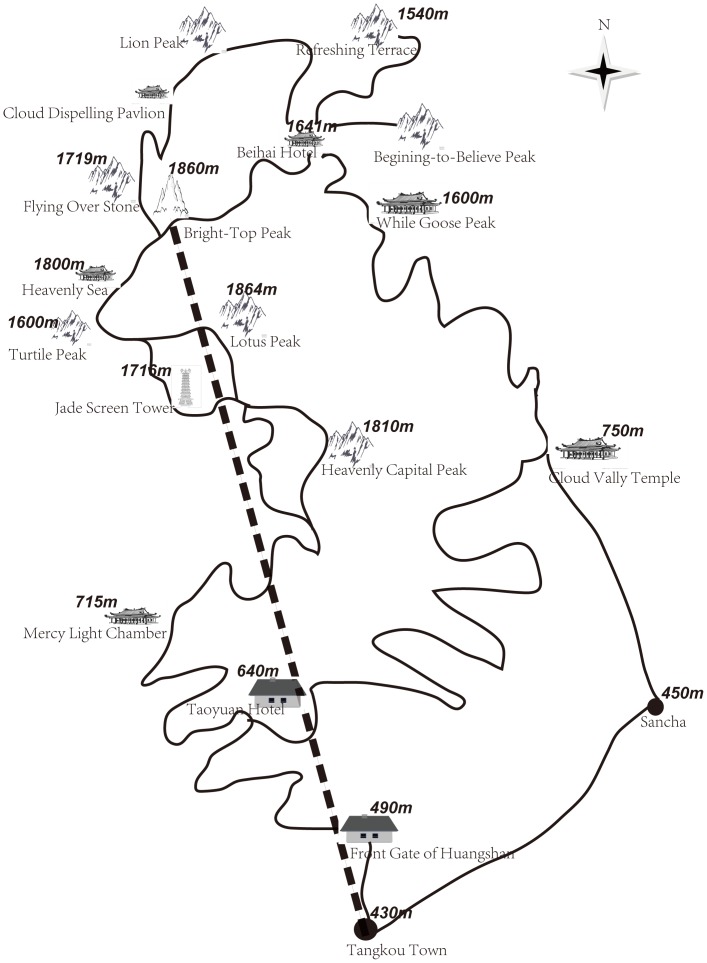

Samples used in this study were collected from Huangshan Mountain in Huangshan, Anhui Province, China. A transect line was set up beginning in the town of Tangkou and ending at Bright Top Peak. Elevations ranged from 450 to 1,820 m (Fig 1). Needles were collected from trees located within 50 m of the transect line. In total, young needles from 270 trees were sampled from the foot to the top of the mountain in 2010. The elevation of each tree was recorded using a ZhengCheng-300 receiver (UniStrong, Beijing, China). We also recorded the breast diameter of each tree (Supporting Information S1). The field studies did not involve any endangered or protected species, and sample collection was authorized by the local administration agency. Total DNA was isolated from the sampled needles using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol [24].

Figure 1. Overview of the Huangshan Mountain sampling strategy.

Note: The transect line (dotted line) started at the town of Tangkou (430 m) and ended at Bright Top Peak (1,820 m).

Microsatellites in pine ESTs were selected from the database established by Yan et al. [25]. A total of 300 primer pairs were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA) and synthesized by Jerry Bio-Technology, Shanghai, China. Using eight DNA templates, we screened the primer pairs to identify those pairs generating distinct and highly polymorphic bands. PCR amplification, genotyping electrophoresis and data collection were performed following the protocols described in Yin et al. [26]. To ascertain the function of the microsatellite-containing ESTs, the corresponding sequences were searched against the NCBI non-redundant (Nr) protein database using BLASTX [27] with an E-value cut-off of 10−5.

Data analyses

Drawing on a previous study of cone morphology and seed characteristics of pine trees from the same Huangshan Mountain sampling area [22], we classified the distribution of our sampled trees into three zones: a P. massoniana zone at elevations below 800 m, a P. hwangshanensis zone at elevations above 1,050 m, and a contact zone corresponding to intermediate elevations. Using POPGEN32 [28], we calculated the number of polymorphic loci (NPL), the percentage of polymorphic loci (PPL), the observed number of alleles (Na), the effective number of alleles (Ne) and Shannon's information index (I) for samples in each species zone. Using the genotyping data, observed heterozygosity (Ho) and mean expected heterozygosity (He) were calculated separately for each SSR marker and for samples in each species zone. Coefficients of inbreeding (FIS) and genetic differentiation (FST) were calculated for samples in each species zone using FSTAT2.9.3 [29]. Gene flow (Nm) was estimated based on Wright's equation [30], Nm = (1−FST)/4FST; selfing rate (S) was estimated according to the formula S = 2FIS/(1+FIS) [31].

To analyze elevation variation in genetic structure and allele frequencies, we divided the transect into nine intervals. Each interval contained approximately 30 samples, and ranged in size from 100 to 200 m depending on tree distribution. Sample genetic structure in each elevation interval was analyzed using STRUCTURE v2.3.3 [32], [33], which estimated the natural logarithm of the probability (Pr) of the observed genotypic array (X) and calculated a pre-defined number of clusters (K) in the data set (ln Pr[X/K]) under the assumption of Hardy-Weinberg and linkage equilibrium [33]. For the STRUCTURE analysis, a Markov chain was run for 2,000,000 iterations after a burn-in of 1,000,000 iterations for values of K from 1 to 10, with five replicates for each K value. The values of the posterior probability of K and membership probabilities (Q) were recorded for each sample. Variation in allele frequencies among the nine elevation intervals was calculated using FSTAT 2.9.3 [29], followed by graphing in EXCEL.

Data Archiving Statement

The raw data underlying the main results of this study, including primer information, sample information and the genotyping data matrix, are archived on our lab website at http://115.29.234.170/Database/Pine.

Results

Genetic parameters associated with each primer pair

In this study, we synthesized and screened 300 SSR primer pairs. Of the tested pairs, 14 generated distinct, highly polymorphic bands (Table 1) and were consequently used to monitor allelic variation between the two studied pine species. A total of 56 alleles were generated, with a mean number of alleles (MNA) per locus of 4 (Table 2). Ho varied dramatically among loci, ranging from 0.0149 to 0.9419, and He accordingly varied from 0.2177 to 0.7538 (Table 2). FST and Nm also differed greatly among loci. The highest level of gene flow, Nm = 251.4594, was observed at loci genotyped by Primer30, and the lowest level was that of Primer149, with Nm = 0.6237 (Table 2). This broad range of values suggests that genetic introgression varied dramatically among different loci.

Table 1. Information on the 14 EST-SSR primers used in this study.

| Locus | Primer sequence 5'-3' | Repeat type | The expected size | EST ID |

| Primer30 | F: CTTCACATTCAACGCTGGCTAC | [TAC]10 | 165 | DT625446 |

| R: CACTATACTGACCCTTACAATTCTTCA | ||||

| Primer33 | F: CGCTATGACCTTTCGTGTT | [TCTTT]4 | 193 | FE522689 |

| R: AATCTATGCCCCAAATTCTT | ||||

| Primer75 | F: TGAGAATGCGTTTCAAAGGTGTAAGC | [CTT]8 | 144 | AM982824 |

| R: GGTTGGCGGAAGCAGCAGAGT | ||||

| Primer89 | F: GAGTCGTGGGATTTACATTCT | [AT]7 | 248 | FE518792 |

| R: ATAGCGATTACAGGGTTGC | ||||

| Primer149 | F: AGCGATGGCGGTTCTGGT | [GGC]7 | 285 | FE523232 |

| R: AGGGAAGGCGTGAGTAGCG | ||||

| Primer150 | F: AAGGAAGAGGAGGTGGAGAC | [GAT]7 | 170 | FG616224 |

| R: TGCTTCTTCGCAAACCTG | ||||

| Primer166 | F: AGAAGGGGTTAATGGAGAA | [GAG]7 | 126 | DT638934 |

| R: TTCAGCAACCAACTTCTAAAT | ||||

| Primer184 | F: ACTTGAATCAGTATCAAGGAGAGGA | [GGAGA]5 | 174 | DT629297 |

| R: AGACTGGACGGCGACATAAAA | ||||

| Primer194 | F: AGCATCAACAGGCACAGCAA | [CAG]13 | 260 | DT625916 |

| R: AGCAGACCCACGCCCAAA | ||||

| Primer221 | F: AGTTCGATTATCAAAATTCTGTATTGGC | [AAG]6 | 223 | DT627258 |

| R: TTGGTTGGGGTGGTTCTGC | ||||

| Primer222 | F: CGCCCTTAATTTCGCCCACT | [AAG]6 | 177 | DT627469 |

| R: CATGAAGCCATCGTTCCCATAA | ||||

| Primer226 | F: AAAGCCACCATTCACAGCA | [CAG]6 | 101 | DT633646 |

| R: GTTTCTTGATAAAGATAAATCCCTC | ||||

| Primer243 | F: CAAGGAGGAGATGTTGACAGGTT | [GAA]6 | 211 | DT625793 |

| R: ATCTGAATCACGACCAACAACG | ||||

| Primer285 | F: TCTGACCGATTTGTGCGA | [ACC]9 | 185 | FE521917 |

| R: GGAAGAAGATACAGCGATATGA |

Table 2. Genetic parameters associated with each of the 14 EST-SSR primers.

| Locus | Number of Alleles | Ho | He | Fst | Nm |

| Primer30 | 2 | 0.9419 | 0.4991 | 0.0010 | 251.4594 |

| Primer33 | 6 | 0.5857 | 0.7176 | 0.0486 | 4.8943 |

| Primer75 | 6 | 0.4093 | 0.7211 | 0.1324 | 1.6385 |

| Primer89 | 5 | 0.0502 | 0.7301 | 0.0445 | 5.3729 |

| Primer149 | 3 | 0.0149 | 0.2177 | 0.2861 | 0.6237 |

| Primer150 | 5 | 0.0950 | 0.6472 | 0.1010 | 2.2260 |

| Primer166 | 4 | 0.4038 | 0.5664 | 0.0832 | 2.7557 |

| Primer184 | 5 | 0.2201 | 0.5071 | 0.2602 | 0.7108 |

| Primer194 | 3 | 0.2313 | 0.2348 | 0.0529 | 4.4758 |

| Primer221 | 3 | 0.2462 | 0.5750 | 0.0566 | 4.1652 |

| Primer222 | 4 | 0.1680 | 0.6180 | 0.0701 | 3.3140 |

| Primer226 | 3 | 0.4407 | 0.5016 | 0.0870 | 2.6234 |

| Primer243 | 5 | 0.5226 | 0.7538 | 0.0230 | 10.6138 |

| Primer285 | 2 | 0.3704 | 0.4938 | 0.2515 | 0.7442 |

| Mean | 4 | 0.3357 | 0.5570 | 0.0955 | 2.3672 |

Note: Ho, He, FST and Nm are defined in Materials and Methods.

Genetic parameters associated with samples from different species zones

Genetic parameters associated with samples from P. massoniana, P. hwangshanensis and contact zones are listed in Table 3. Among these parameters, Na, Ne, I, Ho, He, NPL and PPL indicate the degree of polymorphism, whereas FIS and S reflect the extent of hybridization among trees within each species zone. Values of the polymorphism-related parameters were highest for samples in the P. massoniana zone, and decreased as the transect approached the P. hwangshanensis zone. A similar variation trend was observed for FIS and S among the three zones, with values of these parameters clearly higher in the P. massoniana zone than in P. hwangshanensis and contact zones. The higher values indicate that hybridization is more frequent among trees within a given species zone than across zones. The high selfing rate consequently suggests that P. massoniana receives less pollen from outside zones than do hybrids and P. hwangshanensis. Comparisons of pairwise FST values (Table 4) revealed that the lowest genetic differentiation was between P. hwangshanensis and contact zones (FST = 0.0138). FST was 0.1334 between P. massoniana and contact zones and 0.1516 between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis zones. An analysis of Nm, the parameter estimating gene flow across species zones, indicated that gene flow between P. massoniana and contact zones (Nm = 1.6241) was slightly higher than that between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis zones (Nm = 1.3991). Gene flow between the contact zone and the P. hwangshanensis zone (Nm = 17.8659), however, was significantly higher than for any other pairwise comparisons.

Table 3. Genetic parameters associated with samples collected from each species zone.

| Collected No. | Elevation interval (m) | No. of samples | Na | Ne | I | Ho | HE | NPL | PPL (%) | FIS | Selfing rate |

| P. massoniana zone | 450–800 | 68 | 3.7857 | 2.6644 | 1.0325 | 0.3373 | 0.5717 | 53 | 94.64 | 0.417 | 0.5886 |

| Contact zone | 800–1050 | 57 | 3.6429 | 2.4114 | 0.9296 | 0.3329 | 0.5220 | 51 | 91.07 | 0.369 | 0.5391 |

| P. hwangshanensis zone | 1050–1820 | 145 | 3.5000 | 2.2977 | 0.8687 | 0.3363 | 0.4887 | 49 | 87.50 | 0.315 | 0.4791 |

| Total | 450–1820 | 270 | 56 |

Note: Na, Ne, I, Ho, He and FIS are defined in Materials and Methods.

Table 4. Pairwise comparison of FST and Nm across species zones.

| FSTNm | P. massoniana zone | Contact zone | P. hwangshanensis zone |

| The P. massoniana zone | - | 0.1334 | 0.1516 |

| The Contact zone | 1.6241 | - | 0.0138 |

| The P. hwangshanensis zone | 1.3991 | 17.8659 | - |

Bayesian admixture analysis and species boundary identification

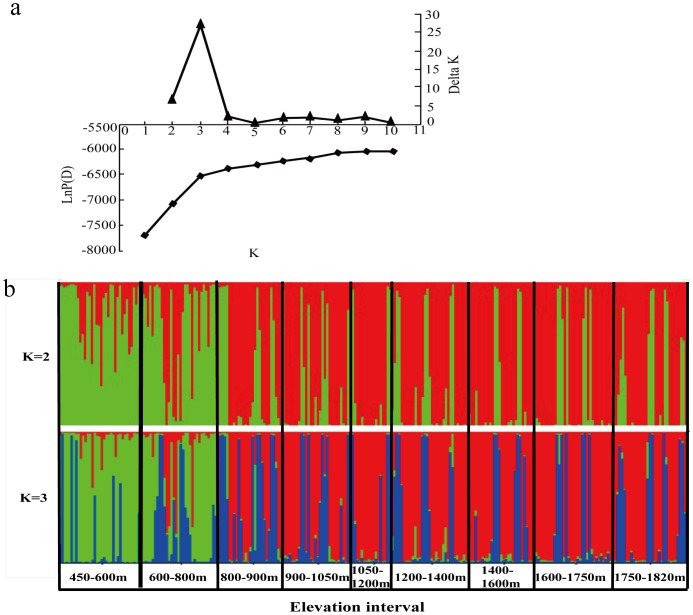

The likelihood of the partition of the data, ln Pr[X/K] increased sharply from K = 1 to K = 3, and then increased slightly from K = 3 to K = 10. Statistically, the optimal number of clusters (K) is determined based on the change in values of ln Pr[X/K] [32]. The partition of the data reached a plateau (Fig. 2a) at K = 3, which was indicated as the optimal number of clusters based on ΔK values. As demonstrated by Fig. 2b, cluster 1 was dominant at low elevation intervals (below 800 m) corresponding to the P. massoniana zone. Cluster 3 was mainly evident within elevation intervals associated with P. hwangshanensis and contact zones. Cluster 2 was widespread in both directions, and represented a population comprising backcrosses between hybrids and their parental species. This analysis indicated that direct gene introgression between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis is fairly low, but that backcrossing occurs intensively in both directions. Because there were only two parental populations in this study, we also performed the STRUCTURE analysis with K = 2. In both cases, the Bayesian admixture analysis clearly indicated that a distinguishable species boundary exists between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis. The uncovered boundary showed that the distribution of P. massoniana is constrained below 800 m, whereas the hybrids and P. hwangshanensis are distributed at higher elevations. The analysis at K = 2, however, only revealed the direct gene introgression between the two species. Previous studies have indicated that the distributions of P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis overlap along a narrow hybrid zone, with trees in the hybrid zone possessing intermediate morphological and anatomical characteristics [14]–[16]. In our earlier studies, seed germination rates of trees in the hybrid zone were found to be significantly lower than those of trees in the parental species zones [22], [34]. Statistically, the optimal number of clusters was calculated as K = 3 rather than K = 2. We propose that the optimal K value of 3 implies the virtual existence of a hybrid zone. Natural hybrid zones have been observed in the distribution of many plant species [8], [9], [35] and play important roles in intermediating gene introgression between parental populations [7]. At K = 3, intensive backcrossing was inferred to occur in both directions, with an indistinct genetic boundary associated with the hybrid zone due to intensive introgression with both parental species. Compare with P. massoniana, P. hwangshanensis was found to backcross with the hybrids more intensively, in agreement with the empirical observation that morphological and anatomical characteristics of trees in the contact zone are biased towards P. hwangshanensis [23]. On the basis of a RAPD marker analysis, Luo and Zou [17] have proposed that gene flow is more intense from P. massoniana to P. hwangshanensis, contrary to the evidence of our study and previous reports [14], [16], [36]. Detailed examination revealed that gene flow into P. hwangshanensis is actually occurring mainly from the hybrids, not from P. massoniana. From a technical standpoint, SSR markers are more reliable and powerful than RAPD markers for population structure analysis [37].

Figure 2. Bayesian admixture analysis of pines sampled within different elevation intervals.

(a) Box-and-whisker diagram of ln Pr[X/K] for 10 runs at each K and ΔK, based on the rate of change of ln Pr[X/K] between successive K values. (b) Bayesian inference of population structure for K = 2 and K = 3. The elevation range was divided into nine intervals. Each interval contained approximately 30 samples and varied in size from 100 to 200 m depending on tree dispersal. Red, green and blue regions correspond to clusters 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

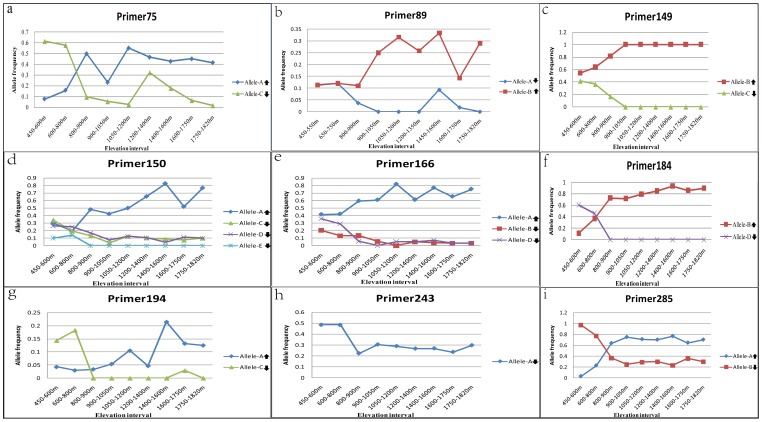

Variation in allele frequencies with elevation

We analyzed the frequencies of alleles generated by the different primer pairs along the divided elevation gradient. After excluding 11 rare alleles (frequency <0.1), the remaining 45 alleles were classified into three types according to their changes in frequency with increasing elevation. Frequencies of 25 alleles (55.56% of 45 alleles) were uncorrelated with elevation (type I; results not shown). We propose that the fitness of these alleles is hardly affected by elevation changes, allowing them to easily introgress into populations at different elevations. Frequencies of 12 alleles (26.67%; type II) were negatively correlated with increasing elevation. We hypothesize that these alleles are well-adapted to the P. massoniana zone; they are selected against at higher elevations, with their introgression hampered to differing extents when migrating towards the P. hwangshanensis zone. Among these type-II alleles, the frequencies of four (alleles C, E, D and C in Fig 3c, d, f and g, respectively) declined to zero in the elevation intervals above either 800 or 1,050 m, indicating that these alleles can not introgress into populations in the high-elevation species zones. Frequencies of the remaining eight alleles (17.78%) were positively correlated with increasing elevation (type III; Fig. 3). Type-III alleles correspond to alleles having good fitness in the P. hwangshanensis zone, but with their introgression blocked to some extent when dispersed towards the P. massoniana zone. As genetic introgression was mainly intermediated by backcrossing, our findings support the hypothesis proposed by Martinsen et al [7], that hybrid zones can act as genomic filters for selective gene introgression, thus maintaining the species boundary associated with type II and type III alleles. In this study, four alleles were found to be constrained only at low elevations, suggesting their potential application in the development of species-specific biomarkers.

Figure 3. Variation in allele frequencies among different elevation intervals.

(a–i) Genetic loci of different primer pairs. Alleles labeled with a down-arrow are type-II alleles, whose frequencies were negatively correlated with increasing elevation; alleles labeled with an up-arrow represent type-III alleles, whose frequencies were positively correlated with increasing elevation. The elevation range was divided as described in Fig. 2. Only type-II and type-III alleles generated by different primers are displayed; type-I alleles, whose frequencies were uncorrelated with elevation, are not shown.

Discussion

Compared with genomic SSR markers EST-SSRs are more informative, as they represent portions of functional genes. Genetic introgression associated with EST-SSRs can be used to monitor the migration of transcribed genes across species. Nevertheless, SSR primers amplify multi-allelic loci, complicating efforts to record genotype data when analyzing samples from natural populations. We screened a large quantity of SSR primers in this study, selecting for use only those primers generating unambiguously scorable genotype profiles. When analyzed with these primers, parameters associated with polymorphism levels were generally found to decrease with increasing elevation. In this study, samples were collected within a defined distance to a transect line that was run from the foot to the top of the mountain. In the sampling area, P. massoniana mixes with broad-leaved trees and has a sparse on-site distribution. With increasing elevation, pure pine stands gradually dominate the forest landscape, with their on-site distribution fairly dense at high elevations. In our collections, the high-elevation samples thus tended to have closer kinship than the low-elevation ones, thereby leading to an underestimation of polymorphism at high elevations.

In this study, we monitored gene flow between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis along an elevation gradient on Huangshan Mountain. Because of its beautiful natural scenery, Huangshan Mountain was established as a natural conservation area in 1934. According to “The History of Huangshan Mountain” [38], pine in this area is a native forest component and the vegetation in this area is naturally regenerated. Pines are anemophilous plants. Gene flow in pine under natural conditions mainly occurs via pollen and seed dispersal. In general, pollen flow impacts genetic diversity within and among plant populations, whereas seed dispersal plays important roles in the colonization of new sites, the reestablishment of extinct populations, and local migration [39]. As a food resource, the cones of P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis might be transferred by rodents across species zones. In pines, however, pollen flow overwhelms seed flow [40]–[42]. Thus, gene introgression between pine species is mainly attributed to pollen flow. The flowering phenology of P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis overlaps from April to May [13]. Because P. hwangshanensis is distributed at high elevations, its pollen should theoretically be easily dispersed to the lower elevation species zone. A RAPD marker-based analysis by Luo and Zou, however, revealed that gene flow is more intense from P. massoniana to P. hwangshanensis [17]. Our study also demonstrated that P. hwangshanensis receives more outside pollen from the other species' zones than does P. massoniana, in agreement at least superficially with Luo and Zou's findings. Nevertheless, population structure analysis revealed that direct gene introgression between the two species is fairly low, with gene flow between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis mainly intermediated via backcrossing. As also indicated by an analysis of gene flow across species zones, genes introgressed into P. hwangshanensis were found to be mainly from the hybrid zone rather than directly from P. massoniana. Consequently, the conclusion that gene flow is more intense from P. massoniana to P. hwangshanensis is not supported by the results of our study.

Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis are naturally distributed in different ecological niches. With increasing elevation, the environmental factors directly affecting plant growth and fitness, such as oxygen partial pressure, air temperature and moisture regime, soil temperature and water regime, and sunlight and ultraviolet light intensity, will also change. These ecological factors will exert selective pressure on internal factors to maintain species integrity. A study by Qu et al. [22] determined that seed plumpness, germination rates and weight per thousand seeds were significantly lower in trees in the contact zone than elsewhere, suggesting reduced hybrid fitness. Reduced hybrid fitness is sometimes the first indication of genetic incompatibilities that may ultimately lead to reproductive isolation and speciation [43]. In the study of some other pine species, findings also supported that some ecological factors (such as geography and environment) could help maintain and reinforce species differentiation and reproductive isolation [44], [45]. Such as Pinus yunnanenis, the geographical and environmental factors together created stronger and more discrete genetic differentiation, the discrete differentiation between two genetic groups is consistent with niche divergence and geographical isolation of these groups [44]. Pinus densata and its parental species have diverged in ecological preferences, some candidate ecological factors associated with habitat-specific adaptation were identified [45]. Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis are distinguishable on the basis of morphological, cytological and timber anatomical characteristics. In this study, we identified a distinct species boundary between their natural distributional ranges. On the other hand, no distinct boundary was detected at the molecular level between hybrid and P. hwangshanensis zones (Fig. 2b). Empirical observation revealed that the contact zone spanned an approximate vertical range of 700–1,000 m that varied between different geographic locations [14], [15], [36]. Species zones revealed by molecular markers were inconsistent with the divisions deduced from empirical observations. Our study results provide strong evidence for intensive mutual gene introgression between the contact zone and the P. hwangshanensis zone, which has resulted in the merging of the two species zones. This finding is consistent with the observation that morphological and anatomical characteristics of trees in the contact zone are biased towards P. hwangshanensis [16], [23].

In this study, 44.44% of amplified alleles were either positively or negatively correlated with increasing elevation. Among these alleles, four were found to be blocked completely from the P. hwangshanensis zone, with introgression ability varying among the other alleles. In general, inner selective pressure is derived from genes that conserve the integrity of the species gene pool, contributing to reproductive barriers [46]. The different introgression abilities of the various alleles may be due to their functional alteration. However, differing numbers of repeats do not normally cause important phenotypic differences among expressed alleles. The impeded alleles are therefore less likely associated directly with the persistence of species integrity, and may simply be linked to selected genes. The genetic recombination distance of alleles and their linkage with genes under different selection pressures would affect allele efficiencies [47]. We developed SSR markers from transcribed genes, but none of the corresponding EST sequences were homologous to genes of known function. Thus, we cannot currently associate introgression abilities of amplified alleles with gene functions.

On the basis of morphological, anatomical, and molecular evidence, natural hybrids have been confirmed in the contact zone between P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis [14], [17], [18]. Excessive introgressive hybridization can lead to genetic swamping and bring about extinction [4], [48], [49]. Barriers to hybridization and interspecific gene flow may thus be vital for the persistence of permanently adjacently distributed species that occur with interfertile hybrids. Hybrid zones can act as genomic sieves. The semi-permeability of species boundaries allows some alleles to pass freely between species while restricting those contributing to reproductive barriers [46]. The above hypothesis is supported by the example of Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii), narrowleaf cottonwood (P. angustifolia) and their hybrids [7]. Fremont cottonwood grows at elevations of approximately 1,300 to 1,500 m throughout the Weber River drainage in the U.S.A., while narrowleaf cottonwood grows at elevations of approximately 1,400 to 2,300 m. The two species overlap in a narrow contact zone marked by the occurrence of extensive hybridization. An RFLP analysis clearly indicated that that hybrid zone acts as a genomic filter for selective gene introgression. Our study has provided additional evidence to aid in the understanding of how adjacently distributed plants maintain species integrity in the face of naturally occurring hybridization.

Conclusions

In this study, we resolved several major controversies arising from previous studies of speciation of two geographically overlapping pine species in the presence of natural hybrids. First, our results demonstrate that direct introgression between these two species is fairly low, with the majority of gene introgression intermediated through backcrossing. Although our findings were superficially in agreement with a previous conclusion that gene flow is more intense from P. massoniana to P. hwangshanensis, a more detailed examination revealed that gene introgression into P. hwangshanensis zone populations was mainly from the hybrid zone, with direct colonization from P. massoniana fairly rare. Second, our study uncovered a distinct boundary between the on-site distributions of P. massoniana and P. hwangshanensis. On the other hand, no distinct boundary was detected between the hybrid zone and the P. hwangshanensis zone. We found that intensive mutual gene introgression between the two species zones led them to merge with each other, consistent with the observation that morphological and anatomical characteristics of trees in the contact zone are biased towards P. hwangshanensis. Third, we determined that introgression ability varied among amplified alleles, with some completely blocked from the opposite species. Our study has provided additional evidence that hybrid zones can act as genomic sieves, thereby allowing neutral alleles to pass freely between species while restricting those contributing to reproductive barriers.

Supporting Information

The elevation and breast diameter of samples collected from Huangshan Mountain in this study.

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhibing Wan for help with sample collection.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All data are available from: http://115.29.234.170/Database/Pine/.

Funding Statement

Natural Science Foundation (31125008, 31270661) Program for Innovative Research Team in Universities of Jiangsu Province and the Educational Department of China. Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) program at Nanjing Forestry University Program of Scientific Innovation Research of College Graduate in Jiangsu Province (CXZZ13-0528). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Abbott R, Albach D, Ansell S, Arntzen JW, Baird SJE, et al. (2013) Hybridization and speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26: 229–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ellstrand NC, Prentice HC, Hancock JF (1999) Gene flow and introgression from domesticated plants into their wild relatives. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30: 539–563. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jensen AB, Palmer KA, Boomsma JJ, Pedersen BV (2005) Varying degrees of Apis mellifera ligustica introgression in protected populations of the black honeybee, Apis mellifera mellifera, in northwest Europe. Molecular Ecology 14: 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levin DA, Francisco-Ortega J, Jansen RK (1996) Hybridization and the extinction of rare plant species. Conservation Biology 10: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Runyeon-Lager H, Prentice HC (2000) Morphometric variation in a hybrid zone between the weed, Silene vulgaris, and the endemic, Silene uniflora ssp. petraea (Caryophyllaceae), on the Baltic island of Öland. Canadian Journal of Botany 78: 1384–1397. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rogers SM, Bernatchez L (2006) The genetic basis of intrinsic and extrinsic post-zygotic reproductive isolation jointly promoting speciation in the lake whitefish species complex (Coregonus clupeaformis). Journal of evolutionary biology 19: 1979–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martinsen GD, Whitham TG, Turek RJ, Keim P (2001) Hybrid populations selectively filter gene introgression between species. Evolution 55: 1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schilthuizen M, Lammers Y (2013) Hybrid zones, barrier loci and the ‘rare allele phenomenon’. Journal of evolutionary biology 26: 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cullingham CI, James P, Cooke JE, Coltman DW (2012) Characterizing the physical and genetic structure of the lodgepole pine × jack pine hybrid zone: mosaic structure and differential introgression. Evolutionary applications 5: 879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold ML (1997) Natural Hybridization and Evolution. In Nature hybridization and species concepts, pp: 20–21. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- 11. Bridle JR, Garn AK, Monk KA, Butlin RK (2001) Speciation in Chitaura grasshoppers (Acrididae: Oxyinae) on the island of Sulawesi: color patterns, morphology and contact zones. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 72: 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vines TH, Kohler SC, Thiel M, Ghira I, Sands TR (2003) The maintenance of reproductive isolation in a mosaic hybrid zone between the fire-bellied toads Bombina bombina and B. variegata . Evolution 57: 1876–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu L, Li N, Elias TS (1999) Flora of China (ed. Wu ZY & Raven PH), pp: v4: : 15–90. Beijing: Science Press; St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xing YH, Fang YX, Wu YG (1992) The preliminary study on natural hybridization between Pinus hwangshanensis and P. massoniana in Dabie Mountian of Anhui province. Journal of Anhui Forestry Science Technology 4: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song YC (1980) Warm-Temperate Coniferous Forest. Chinese vegetation (ed. Wu ZY), pp: 234–241. Science Press. Beijing: China. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qi CJ, Lin QZ (1988) A new variant of Pinus massoniana . Botanical Research 3: 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luo SJ, Zou HY (2001) Study on the introgressive hybridization between pinus hwangshanensis and P. massoniana . Scientia Silvae Sinicae 37: 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou YF, Abbott RJ, Jiang ZY, Du FK, Milne RI (2010) Gene flow and species delimitation: a case study of two pine species with overlapping distributions in southeast China. Evolution 64: 2342–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Du FK, Peng XL, Liu JQ, Lascoux M, Hu FS, et al. (2011) Direction and extent of organelle DNA introgression between two spruce species in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. New Phytologist 192: 1024–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang B, Mao JF, Gao J, Zhao WE, Wang XR (2011) Colonization of the Tibetan Plateau by the homoploid hybrid pine Pinus densata . Molecular ecology 20: 3796–3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watano Y, Kanai A, Tani N (2004) Genetic structure of hybrid zones between Pinus pumila and P. parviflora var. pentaphylla (Pinaceae) revealed by molecular hybrid index analysis. American Journal of Botany 91: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qu JT, Yan MM, Dai XG, Li SX (2012) Variation in cone morphology and seed characteristics for Pinus massonian Lamb., P. taiwanensis Hayata, and their hybrid zone. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (natural science edition) 36: 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen ZY (1986) The natural hybridization of Pinus massoniana and P. huangshanesis in Anhui. The collected paper of South China Institute of botany 1: 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan MM, Dai XG, Li SX, Yin TM (2012) A Meta-Analysis of EST-SSR Sequences in the Genomes of Pine, Poplar and Eucalyptus. Tree Genetics and Molecular Breeding 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yin TM, DiFazio SP, Gunter LE, Riemenschneider D, Tuskan GA (2004) Large-scale heterospecific segregation distortion in Populus revealed by a dense genetic map. Theoretical and applied genetics 109: 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeh FC, Yang R, Boyle T (1999) POPGENE, version 1.31. Microsoft Window-based freeware for population genetic analysis, University of Alberta. Edmonton, Canada.

- 29.Goudet J (2001) FSTAT, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices (version 2.9.3).

- 30.Wright S (1978) Evolution and the Genetics of Populations. Variability Within and Among Natural Populations (ed. Wright S), Vol. 4 . University of Chicago Press; Chicago: IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crow JF, Kimura M (1970). An introduction to population genetics theory. An introduction to population genetics theory. Harper and Row, New York.

- 32. Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2003) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164: 1567–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li SX, Chen Y, Gao HD, Yin TM (2010) Potential chromosomal introgression barriers revealed by linkage analysis in a hybrid of Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis . BMC Plant Biology 10: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang BS, Mao JF, Gao J, Zhao W, Wang XR (2011) Colonization of the Tibetan Plateau by the homoploid hybrid pine Pinus densata . Molecular Ecology 20: 3796–3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ke BF, Li SC, Wei GY (1983) The secondary discussion on the nomenclature for Pinus hwangshanensis . Journal of Anhui Agricultural University 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Panwar P, Saini RK, Sharma N, Yadav D, Kumar A (2010) Efficiency of RAPD, SSR and cytochrome P450 gene based markers in accessing genetic variability amongst finger millet (Eleusine coracana) accessions. Molecular biology reports 37: 4075–4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang WB (2008) The history of Huangshan Mmountain. pp: 320–322. Huangshan Press. Huangshan City, China.

- 39. Barluenga M, Austerlitz F, Elzinga JA, Teixeira S, Goudet J, et al. (2011) Fine-scale spatial genetic structure and gene dispersal in Silene latifolia . Heredity 106: 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dong J, Wagner DB (1993) Taxonomic and population differentiation of mitochondrial diversity in Pinus banksiana and Pinus conforta . Theoretical and Applied Genetics 86: 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ennos R (1994) Estimating the relative rates of pollen and seed migration among plant populations. Heredity 72: 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strauss SH, Hong YP, Hipkins VD (1993) High levels of population differentiation for mitochondrial DNA haplotypes in Pinus radiata, muricata, and attenuata . Theoretical and Applied Genetics 86: 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ronald SB, Ricardo JP, Felipe SB (2013) Cytonuclear genomic interactions and hybrid breakdown. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 44: 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang BS, Mao JF, Zhao W, Wang XR (2011) Impact of Geography and Climate on the Genetic Differentiation of the Subtropical Pine Pinus yunnanensis . PLoS ONE 8: e67345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mao JF, Wang XR (2011) Distinct Niche Divergence Characterizes the Homoploid Hybrid Speciation of Pinus densata on the Tibetan Plateau. American Naturalist 177: 424–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kawakami T, Butlin RK (2012) Hybrid Zones. Evolution & Diversity of Life 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barton NH, Gale KS (1993) Genetic analysis of hybrid zones. In: Harrison RG, ed. Hybrid zones and the evolutionary process, pp: 13–45. Oxford University Press, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rhymer JM, Simberloff D (1996) Extinction by hybridization and introgression, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 27: 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wolf DE, Takebayashi N, Rieseberg LH (2001) Predicting the risk of extinction through hybridization. Conservation Biology 15: 1039–1053. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The elevation and breast diameter of samples collected from Huangshan Mountain in this study.

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All data are available from: http://115.29.234.170/Database/Pine/.