Summary

Background

Cardiac dual-source computed tomography (DSCT) is primarily used for coronary arteries. There are limited studies about the application of DSCT for congenital heart diseases. The aim of this study was to determine the diagnostic value of DSCT in the cardiac anomalies.

Material/Methods

The images of DSCTs and conventional angiographies of 36 patients (21 male; mean age: 8.5 month) with congenital heart diseases were reviewed and the parameters of diagnostic value of these methods were compared. Cardiac surgery was the gold standard.

Results

A total of 105 cardiac anomalies were diagnosed at surgery. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of DSCT were 98.25%, 97.9%, 98.1%, 99.07%, and 98.2%, respectively. The corresponding values of angiography were 95.04%, 98.7%, 97.8%, 98.1%, and 98%, respectively. Only one atrial septal defect (ASD) and two patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) were missed by DSCT. Angiography missed two ASD and two PDA. DSCT also provided important additional findings (n=35) about the intrathoracic or intraabdominal organs.

Conclusions

DSCT is a highly accurate diagnostic modality for congenital heart diseases, obviating the need for invasive modalities. Beside its noninvasive nature, the advantage of DSCT over the angiography is its ability to provide detailed anatomical information about the heart, vessels, lungs and intraabdominal organs.

MeSH Keywords: Angiography, Heart Defects, Congenital, Multidetector Computed Tomography

Background

Dual-source computed tomography (DSCT) is an advanced imaging method which provides more detailed images than single-source multi-slice CT and also entails radiation exposure lower than conventional angiography [1,2]. Although cardiac DSCT (DSCT angiography) is mainly used for coronary evaluation and when applied for that purpose, it shows high diagnostic accuracy [1,3,4], it also visualizes nonvascular structures of the heart such as cardiac walls, septa, and valves [1,5,6]. Using DSCT, Cheng et al. detected 146 separate cardiovascular deformities in 35 patients; DSCT missed only three atrial septal defects and one patent ductus arteriosus [5].

There is limited experience with application of DSCT for cardiac diseases. The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic value of DSCT in congenital heart diseases (CHD) and to compare it with angiography.

Material and Methods

This study included 36 patients (21 male; mean age: 8.5 month) with CHD who underwent surgery (30 open and 6 closed cardiac surgeries; 9 cases of two or more surgeries in different ages). Non-ECG-gated DSCT (256-slice, SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Medical Solutions, Germany) and conventional angiography (HICOR System, Siemens, Germany) were carried out for all patients. DSCTs and angiographies were clinically indicated and the authors did not play any role in requesting images; all patients were referred to our imaging center by pediatric cardiologists or cardiosurgeons. Written consent was obtained from the parents of all subjects.

In the 256-slice dual-source scanner the tube effective current was 45 to 95 mAs, depending on patients’ weight and the tube voltage was set at 90–120 kV, depending on patients’ body mass index. Tube rotation time and table feed were 350 ms and 30 mm/rotation, respectively. Two mL/kg of non-ionic contrast medium (Iopromide, 370 mg iodine per mL, Ultravist 370, Schering, Berlin, Germany), followed by the same amount of saline flush, was injected at a mean flow rate of 3 mL/s. Images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.75 mm and an interval of 0.4 mm.

Conventional cardiac angiography was performed based on the standard Seldinger’s technique by femoral approach.

All DSCT images were interpreted by two experienced radiologists with substantial interobserver agreement; kappa=0.79. Angiographies were interpreted by two experienced cardiologists with substantial interobserver agreement; kappa=0.75. Parameters of diagnostic value (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value [PPV], negative predictive value [NPV] and diagnostic accuracy) of DSCT were determined and compared with those of conventional angiography. Surgery was considered as a gold standard.

Statistical analysis was performed by means of SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 105 separate cardiac anomalies were diagnosed with surgery in 36 patients. Most patients had complex cardiac anomalies. However, we described all detected anomalies individually, irrespective of the name of special complex anomalies. A comparison of detection rates of DSCT and angiography for all cardiac anomalies were summarized in Table 1 and some examples of anomalies detected by DSCT were shown in Figures 1–4.

Table 1.

Comparison of detection rate of DSCT and conventional angiography in congenital heart diseases.

| Cardiac anomalies | Total number | Detected by DSCT | Detected by angiography | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSD | 19 (18.1%) | 19 (100.0%) | 19 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| ASD | 16 (15.2%) | 15 (93.75%) | 14 (87.5%) | >0.05 |

| PDA | 11 (10.5%) | 9 (74.3%) | 9 (74.3%) | >0.05 |

| Pulmonary atresia | 11 (10.5%) | 11 (100.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| TGA | 7 (6.7%) | 7 (100.0%) | 7 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 6 (5.7%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| PAH | 6 (5.7%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Pulmonary stenosis | 5 (4.8%) | 5 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Rt. aortic arc | 4 (3.8%) | 4 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| TAPVC | 4 (3.8%) | 4 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Dextrocardia | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (100.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| DORV | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (100.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Aortic stenosis | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (100.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| CAVSD | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (100.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Mitral stenosis | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Double SVC | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Interrupted aortic arc | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Mitral atresia | 1 (0.95%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Rt. ventricle hypoplasia | 1 (0.95%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Lt. ventricle hypoplasia | 1 (0.95%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | >0.05 |

| Total | 105 (100.00%) | 102 (97.14%) | 101 (96.19) | >0.05 |

VSD – ventricular septal defect; ASD – atrial septal defect; PDA – patent ductus arteriosus; TGA – transposition of great vessels, PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension; DORV – double outlet of right ventricle; TAPVC – total anomalous pulmonary vein connections; CAVSD – complete A-V septal defects.

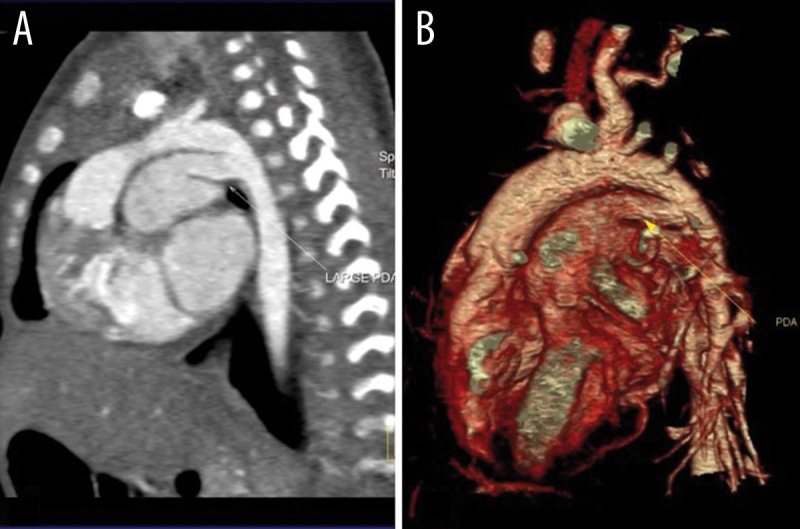

Figure 1.

Sagittal reconstructed (A) and volume rendering (B) dual source CT images of a 15-day girl with a large PDA and PAH. (PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension).

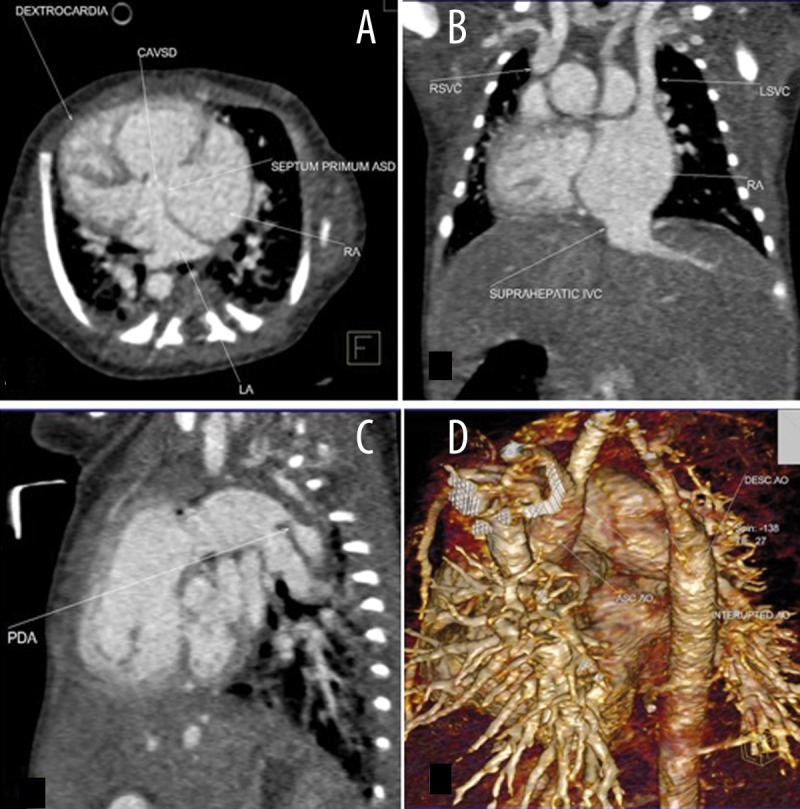

Figure 4.

Multiplanar axial (A), coronal (B), sagittal (C), and volume rendered (D) images of a 4-day-old boy with CAVSD, dextrocardia, interrupted aortic arc type a, double SVC (CAVSD: complete A-V septal defects; RSVC & LSVC: right and left SVC).

Diagnostic accuracy of DSCT (98.2%) was similar to that of angiography (98%). DSCT missed only one atrial septal defect (ASD) and two PDAs (patent ductus arteriosus); all of them were also missed in angiography due to a very small size. Angiography missed another PDA as well.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value [PPV], negative predictive value [NPV] of DSCT were 98.25%, 97.9%, 98.1%, and 99.07%, respectively. The corresponding values for angiography were 95.04%, 98.7%, 97.8%, and 98.1%, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the two methods.

Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference between DSCT and angiography in the detection of extracardiac vascular anomalies (including right aortic arch, trancus arteriosus, TAPVC, left or double SVC and coarctation of the aorta).

DSCT detected 8 cases of coronary anomalies and all of them were confirmed by surgery and angiography. There was no correlation between the coronary anomalies and congenital heart disease.

Coronary anomalies were as follows:

Origin of the right coronary artery (RCA) from the left main coronary artery (LCA).

Origin of the RCA from the LCA and origin of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) from the distal LCA.

LCA arising from the posterior noncoronary sinus; origin of the left circumflex artery (LCX) from the RCA; dilatation of the proximal RCA and abnormal course of the RCA.

Single coronary artery.

LCA arising from the noncoronary sinus.

RCA arising from the LAD; prepulmonary course of the LAD and retroaortic course of the LCX.

Origin of the RCA from noncoronary sinus.

Origin of the LAD from the RCA.

Another important finding in this study was detection of 35 separate noncardiac abnormalities in the thoracic or abdominal organs including pulmonary opacity or consolidation (n=8), situs inversus/ambiguus (n=4), asplenia (n=3), vertebral anomalies (n=3), collateral vessels from the aorta or bronchial arteries (n=3), hepatomegaly (n=3), pleural effusion (n=2), pericardial effusion (n=2), pulmonary collapse/atelectasis (n=2), aberrant right subclavian artery (n=2), abdominal mass suggestive of neuroblastoma (n=1), pneumothorax (n=1), and aortic wall hematoma (n=1).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that DSCT has high diagnostic accuracy similar to angiography. Moreover, there were no statistically significant differences between these methods in sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. These findings are similar to those of Cheng et al. study; they detected 146 separate cardiovascular deformities in 35 patients by low-dose prospective ECG-triggering DSCT [5]. In our study, the gold standard was surgery and we showed that the accuracy of DSCT is similar to that of angiography, while Cheng et al. considered either surgery or angiography as the gold standard.

DSCT missed only one ASD and two PDA. None of those anomalies were isolated and all 3 patients had a complex cardiac disease with other anomalies being diagnosed with DSCT. Similarly, Cheng et al. demonstrated that DSCT missed three ASD and one PDA [5].

Studying 50 patients with CHD, Jie et al. compared DSCT with TTE considering angiography or surgery as the gold standard. A total of 107 anomalies were detected. Diagnostic accuracy of DSCT was 95.33%. Diagnostic rate of DSCT did not differ from TTE for intracardiac anomalies (96.67% vs. 93.33%); while the diagnostic rate of DSCT for extracardiac anomalies (96.1%) was significantly higher than that of TTE (87.01%)[6]. In our study, there were no statistically significant differences between DSCT and angiography in detecting cardiovascular anomalies. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of DSCT for coronary anomalies were all 100%. Yang et al. in a study of 46 patients with coronary disease demonstrated that sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of DSCT were 100%, 98%, 99%, and 100%, respectively [7]. The value of cardiac CT in diagnosing coronary and great vessel anomalies was confirmed by other studies [8–10]. Because of higher temporal and spatial resolution of cardiac DSCT, it is clearly logical that application of DSCT can yield better outcomes.

Clinical experience on DSCT in the diagnostics of cardiac anomalies is limited. However, several studies on multidetector CT revealed that this method has high diagnostic accuracy, i.e. of up to 98% [11–13]. With regard to better quality of DSCT images, it is easily expectable that DSCT will have at least similar accuracy for cardiac abnormalities [14].

An important advantage of DSCT over angiography is the fact that DSCT can visualize detailed structures of noncardiac organs within the thorax or abdomen and is able to detect underlying diseases which sometimes can affect the surgical plan or patient’s outcome [15]. In this study, DSCT detected 35 separate intrathoracic or intraabdominal conditions that were mostly undetected by angiography.

Conclusions

DSCT is a noninvasive and highly accurate diagnostic modality for congenital heart diseases. Application of dual-source CT may obviate the need for invasive intracardiac diagnostic modalities. Apart from its noninvasiveness, other advantages of DSCT over angiography include easy and fast performance, and ability to provide detailed anatomical information about the heart, vessels, lungs and intraabdominal organs.

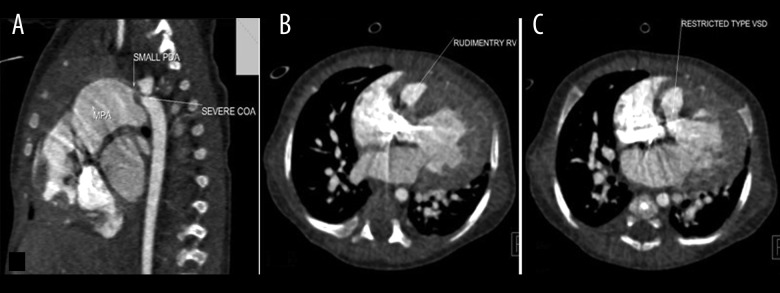

Figure 2.

Multiplanar sagittal (A) and axial (B, C) images of dual source CT in a 2-month-old boy with cyanosis show restrictive VSD, rudimentary RV, functionally single ventricle, severe CoA, small PDA and PAH. (VSD – ventricular septal defect; RV – right ventricle; CoA – coarctation of the aorta; PDA – patent ductus arteriosus; PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension).

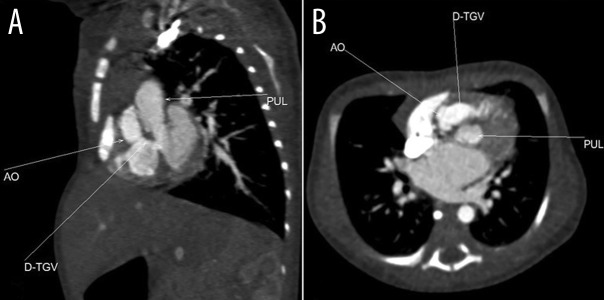

Figure 3.

Axial and coronal reconstructed views of complete transposition of great vessels (D-TGV).

References

- 1.Flohr TG, McCollough CH, Bruder H, et al. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:256–68. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schardt P, Deuringer J, Freudenberger J, et al. New x-ray tube performance in computed tomography by introducing the rotating envelope tube technology. Med Phys. 2004;31:2699–706. doi: 10.1118/1.1783552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheffel H, Alkadhi H, Plass A, et al. Accuracy of dual-source CT coronary angiography: first experience in a high pre-test probability population without heart rate control. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2739–47. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0474-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo F, Liu C, Zhu Y, et al. Study on the accuracy of dual source computed tomography coronary angiography in detection of coronary artery stenoses in old patients. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;41(6):1029–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng Z, Wang X, Duan Y, et al. Low-dose prospective ECG-triggering dual-source CT angiography in infants and children with complex congenital heart disease: first experience. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(10):2503–11. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jie W, Qing W, FegYu C. Application of dual source CT in congenital heart diseases. J Shandong Univers. 2009;47(4):87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Gai L, Li P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of dual-source CT angiography and coronary risk stratification. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;21(6):935–41. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S13879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Z, Wang X, Duan Y, et al. Detection of coronary artery anomalies by dual-source CT coronary angiography. Clin Radiol. 2010;65(10):815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang LJ, Yang GF, Huang W, et al. Incidence of anomalous origin of coronary artery in 1879 Chinese adults on dual-source CT angiography. Neth Heart J. 2010;18(10):466–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03091817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beier UH, Jelnin V, Jain S, et al. Cardiac computed tomography compared to transthoracic echocardiography in the management of congenital heart disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68(3):441–49. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanaati H, Motevalli M, Tabib A, et al. Multidetector CT evaluation of congenital heart disease: a pitcorial essay. Iran J Radiol. 2007;4(4):209–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee T, Tsai IC, Fu YC, et al. Using multidetector-row CT in neonates with complex congenital heart disease to replace diagnostic cardiac catheterization for anatomical investigation: initial experiences in technical and clinical feasibility. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(12):1273–82. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goo HW, Park I, Ko JK, et al. CT of Congenital Heart Disease: Normal Anatomy and Typical Pathologic Conditions. Radiographics. 2003;23:147–65. doi: 10.1148/rg.23si035501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnino R, Jacobs JE, Doshi JV, et al. Dual-source versus single-source cardiac CT angiography: comparison of diagnostic image quality. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1051–56. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vishniakova MV. X-ray study in infants of the first year of life who had congenital heart diseases: traditions, specific features, new capacities. Vestn Rentgenol Radiol. 2004;(4):10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]