Abstract

For ∼30 million years, the eggs of Hawaiian Drosophila were laid in ever-changing environments caused by high rates of island formation. The associated diversification of the size and developmental rate of the syncytial fly embryo would have altered morphogenic gradients, thus necessitating frequent evolutionary compensation of transcriptional responses. We investigate the consequences these radiations had on transcriptional enhancers patterning the embryo to see whether their pattern of molecular evolution is different from non-Hawaiian species. We identify and functionally assay in transgenic D. melanogaster the Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers from two different Hawaiian Drosophila groups: (i) the picture wing group, and (ii) the modified mouthparts group. We find that the binding sites in this set of well-characterized enhancers are footprinted by diverse microsatellite repeat (MSR) sequences. We further show that Hawaiian embryonic enhancers in general are enriched in MSR relative to both Hawaiian non-embryonic enhancers and non-Hawaiian embryonic enhancers. We propose embryonic enhancers are sensitive to Activator spacing because they often serve as assembly scaffolds for the aggregation of transcription factor activator complexes. Furthermore, as most indels are produced by microsatellite repeat slippage, enhancers from Hawaiian Drosophila lineages, which experience dynamic evolutionary pressures, would become grossly enriched in MSR content.

Introduction

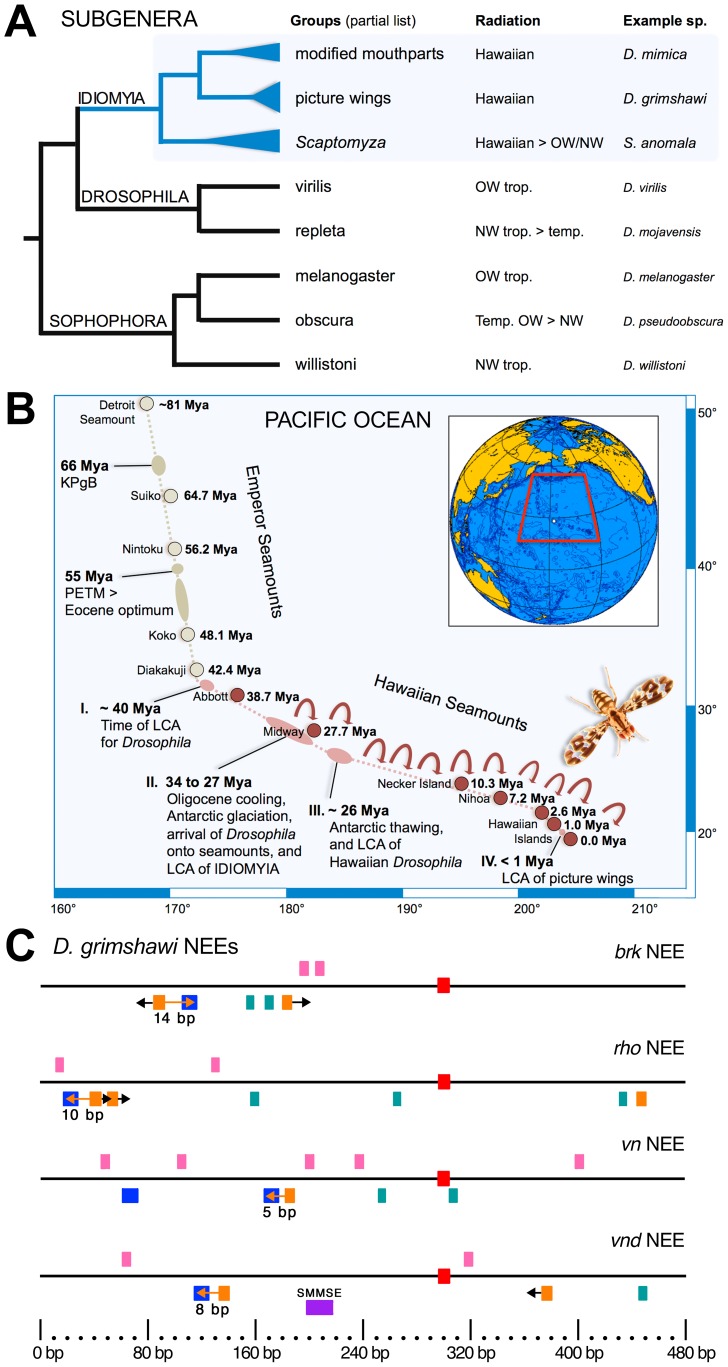

Genomic sequences from twelve ecomorphologically diverse Drosophila species have been assembled [1] and studied [1]–[6]. One of these twelve species, D. grimshawi, is from the large “picture wing” group, which itself is one of many groups of the remarkably speciose Hawaiian Drosophila, corresponding to almost 500 of the ∼1500 described Drosophila species and others yet to be adequately described [7]–[16]. The Hawaiian species form a monophyletic group and include recent radiations exemplified by the picture wing group, which diverged from a most recent common ancestor less than one million years ago (∼0.5–0.7 Mya), older radiations such as that exemplified by the “modified mouthparts” group, and older still the so-called Scaptomyza flies (Fig. 1A). Thus, the Drosophila subgenus, known as IDIOMYIA (Hawaiian Drosophila+Scaptomyza) illustrates the profound species fecundity of the island forming process that in ∼40 million years produced the Hawaiian seamount island chain, which was colonized by Drosophila over ∼30 million years ago (Fig. 1B).

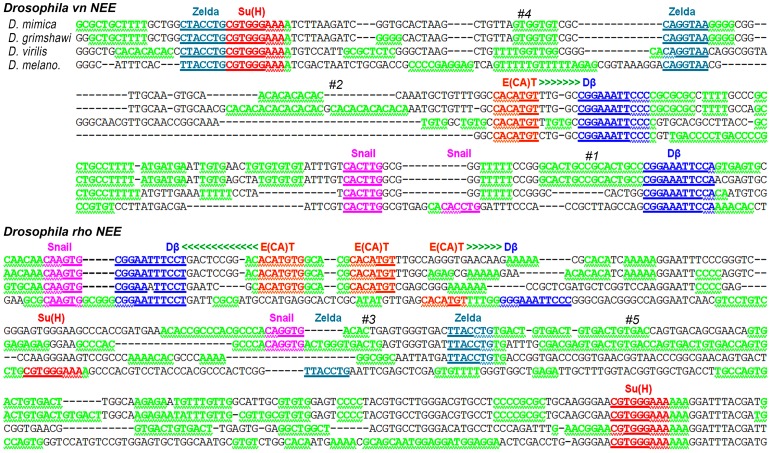

Figure 1. The Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers from the Hawaiian species D. grimshawi.

(A) Shown is a phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the Hawaiian Drosophila, which comprise subgenus IDIOMYIA along with the so-called Scaptomyza [16]. This subgenus gave rise to multiple clades (highlighted in blue) corresponding to multiple adaptive radiations associated with the last ∼30 My history of island formation. Embryonic enhancers from two of these clades, the modified mouthparts group and the picture wing group, are analyzed in this study. (B) Shown is a map of the Hawaiian Seamounts with relevant events in the evolutionary lineage leading to the Hawaiian Drosophila groups indicated by the ages of the various islands. The picture wing group (inset shows an example D. grimshawi adult fly) is one of the most recent radiations and is closely associated with the newest and easternmost front of the seamounts, i.e., the Hawaiian islands. (C) The graphs indicate the site architecture of the four genus-canonical Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers (NEEs), which we identified in the D. grimshawi genome. The NEEs are a class of early embryonic enhancers downstream of the Dorsal morphogen gradient [4], [5], [19]. The search for NEEs in the D. grimshawi genome was conducted by searching for linked sites for the Twist:Daughterless bHLH heterodimer (Twi:Da) and the rel homology domain-containing TF Dorsal (5′-CACATGT 0–41 bp GGAAABYCC), plus a nearby Su(H) site binding site located up to +/−300 bp away (see Material & Methods). Three horizontal tracks indicate sequences matching different TF binding motifs (tracks are separated to avoid overlap and for ease of visualization when viewed in black & white print or with color-blindness). Above line: pink boxes = Snail (5′-CARRTG) [57]. On line: red boxes = Su(H) (5′-YGTGRGAA). A single Su(H) site is present in each enhancer and is used to anchor each sequence at basepair position 300 bp [the Su(H) motif matches the top strand for all except in the vn NEE]. Below line: orange boxes = Twist:Daughterless (Twi:Da, 5′-CACATGT); blue boxes = Dorsal (5′-VGGAAABYCCV); blue and orange boxes connected by arrow = linked Twi:Da–Dorsal sites with text indicating spacer length; and purple boxes = Shnurri:Mad:Medea Silencer Element (SMMSE). The Schnurri/Mad/Medea Silencer Element (SMMSE), which functions to constrain the dorsal border of activity for the NEE at vnd [19], matches the D. melanogaster/D. grimshawi consensus 5′-MYGGCGWCACACTGTCTGS and is highlighted in purple.

We consider the consequences of the sustained pattern of frequent species radiations on transcriptional enhancers of the syncytial fly embryo within Hawaiian Drosophila. In this evolutionary context, the evolving Drosophila egg is being laid in new and ever-changing environments. The associated evolutionary diversification of the syncytial fly embryo (viz., the shape, size, and developmental rate of the embryo as previously shown [17], [18]) would have continuously altered embryonic morphogen gradients of each lineage, thus necessitating compensatory evolution of the gradient-sensing responses of target enhancers [4]. We therefore ask whether the pattern of molecular evolution at developmental enhancers that interpret embryonic morphogen gradients in Hawaiian Drosophila differs from that in non-Hawaiian Drosophila.

To address this question, we considered a group of complex transcriptional enhancers that are important to Drosophila morphogenesis: the Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers (NEEs) [4], [5], [19], [20]. Unlike protein-coding gene families, which are related by common descent (i.e., homology), the NEEs in a single genome are similar only by molecular convergence (parallelism) and so we define them as a mechanistic “family”. Four “canonical” NEEs are present as orthologs across the genus in the unrelated loci rhomboid (rho), vein (vn), brinker (brk), and ventral nervous system defective (vnd) [4], [5], [19]–[21]. The NEEs are responsive to the morphogenic gradient of Dorsal, which patterns the dorsal/ventral axis of the early embryo. While Dorsal is a homolog of the NFkB-enhanceosome forming factor, and is known to work with many different co-activator transcription factors (TFs) along the D/V axis [22], we found that the NEEs contain binding sites for a specific subset of these factors. Binding sites for the activators, Dorsal, Twist, Su(H), and the mesodermal repressor Snail are present in each of the NEEs we have found [4], [20], which is consistent with the NEEs representing one specific equivalence class of enhancers; there exist other lateral stripe enhancers and sometimes even lateral stripe “shadow enhancers” [4], [23]–[26] at the same NEE-bearing loci, but they feature binding sites for distinctly different sets of factors other than Dorsal.

Here, we identify and analyze the evolutionary divergence of NEEs in one representative species of the Hawaiian picture wing group, which has a fully sequenced genome (D. grimshawi) [1], and in one representative species of the Hawaiian modified mouthparts group (D. mimica), for which we cloned, sequenced, and tested their enhancers. We show that relative to D. virilis, which is a representative of the continental Old World group of the subgenus DROSOPHILA that gave rise to the Hawaiian Drosophila, the intervening DNA sequences between the NEE binding sites have been largely replaced by microsatellite repeat (MSR) sequences. This unique MSR-footprint demarcates the functional binding sites for Dorsal, Twist/Snail, and Su(H). It also demarcates the dedicated Snail binding sites and sites for the general embryonic timing factor Zelda. We also demonstrate that relative enrichment of MSR in Hawaiian Drosophila is specific to developmental enhancers of embryogenesis and suggests that diverse enhancers function as enhanceosome scaffolds with sensitive spacing requirements. Because Dorsal, Twist, Su(H), and Zelda are all polyglutamine-rich transcriptional activators, we propose a specific model in which enhancers functioning as scaffolds for polyglutamine-mediated co-factor complexes are both sensitive to cis-element spacing and are sites of MSR-enrichment when subjected to evolutionary pressures.

Results

Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers (NEEs) from Hawaiian Drosophila

To identify the repertoire of NEE functions in a Hawaiian Drosophila species, we used the assembled genome from the Hawaiian picture wing fly, D. grimshawi (Fig. 1A, and adult pictured in Fig. 1B inset). Specifically, we searched for a Su(H)-binding motif (5′-YGTGRGAA) located within 300 bp of linked Twist and Dorsal binding sites (5′-CACATGT 0–40 bp nGGAAABYCCn, where the Dorsal site could be in any orientation and the n’s are included here only to indicate the normal extent of the Dorsal binding site; see methods). We find only the four genus-canonical NEEs at brk, rho, vn, and vnd, each having linked Dorsal and Twist binding sites with spacers of length 14 bp, 10 bp, 5 bp, and 8 bp, respectively (Fig. 1C). Previously, we showed the length of the spacer separating these linked Dorsal and Twist sites to be a major determinant of the extent to which the NEE is responsive to the Dorsal morphogen [4], [5].

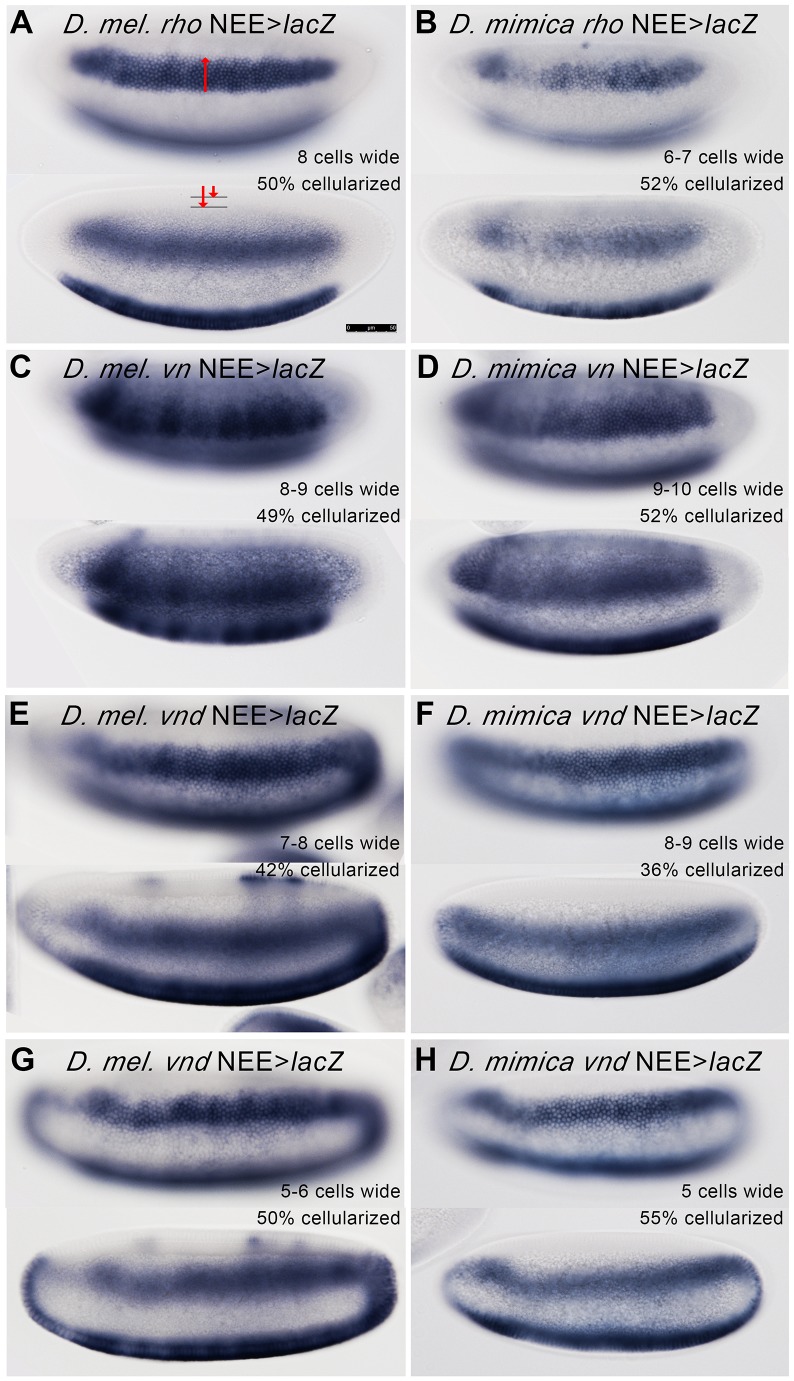

We then designed primers on the basis of the NEE sequences in D. grimshawi, and successfully amplified intact fragments, ∼500 to 600 bp in length, containing the NEEs from the rho, vn, and vnd loci from a Hawaiian modified mouthparts fly, D. mimica, which we have begun culturing in the lab (see Methods). We made standard fusion reporter genes using the −42 eve:lacZ β-tub 3′-UTR reporter construct in a P-element vector and transformed them into D. melanogaster to test for function. All three of these enhancers are bona fide NEEs by definition of their site composition and organization, and have discernible neuroectodermal enhancer activity in D. melanogaster embryos despite ∼40 million years of evolution in addition to the accelerated levels of evolution in the Hawaiian system (Fig. 2). We find that the vnd NEE still encodes a predicted low threshold response that drives early expression, when the Dorsal nuclear gradient is still increasing ventrally [27], but a later dorsally-repressed expression pattern due in part to a well-conserved Schnurri/Mad/Medea silence element [19] (Fig. 2, E–H).

Figure 2. The NEEs from D. mimica Can Drive Expression in Neurogenic Ectoderm of D. melanogaster Despite Replacement of Inter-Element Spacers with MSR.

NEEs from the D. mimica, a member of the Hawaiian modified mouthparts clade, were cloned and tested in D. melanogaster transgenic reporter assays. Expression of the lacZ reporter gene driven from D. melanogaster NEEs (A, C, E, G) and D. mimica NEEs (B, D, F, H) as determined by in situ hybridization with an anti-lacZ probe are shown. In each panel two optical cross-sections are shown. The top image is a surface view allowing determination of the stripe of expression (numbers of cells spanning D/V axis). The bottom image is a cross-section through the dorsal midline allowing determination of the exact stage of embryogenesis (% cellularization as determined at 50% egg length on the dorsal midline). The expression patterns driven by the rho (A, B) and vn (C, D) NEEs are shown for the stages close to 50% cellularization. The expression patterns for the vnd NEEs are shown at two time points: an earlier time point at about ∼40% cellularization (E, F) and a later time point at ∼50% cellularization (G, H). For both Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian vnd NEEs, activity is dorsally repressed by the the Dpp gradient via a conserved binding site for the Shnurri:Mad:Medea complex beginning at about midway through cellularization [19]. All embryos are oriented with anterior pole to the left and dorsal side on top. The 50 micron scale bar shown in (A) is the same for all figures.

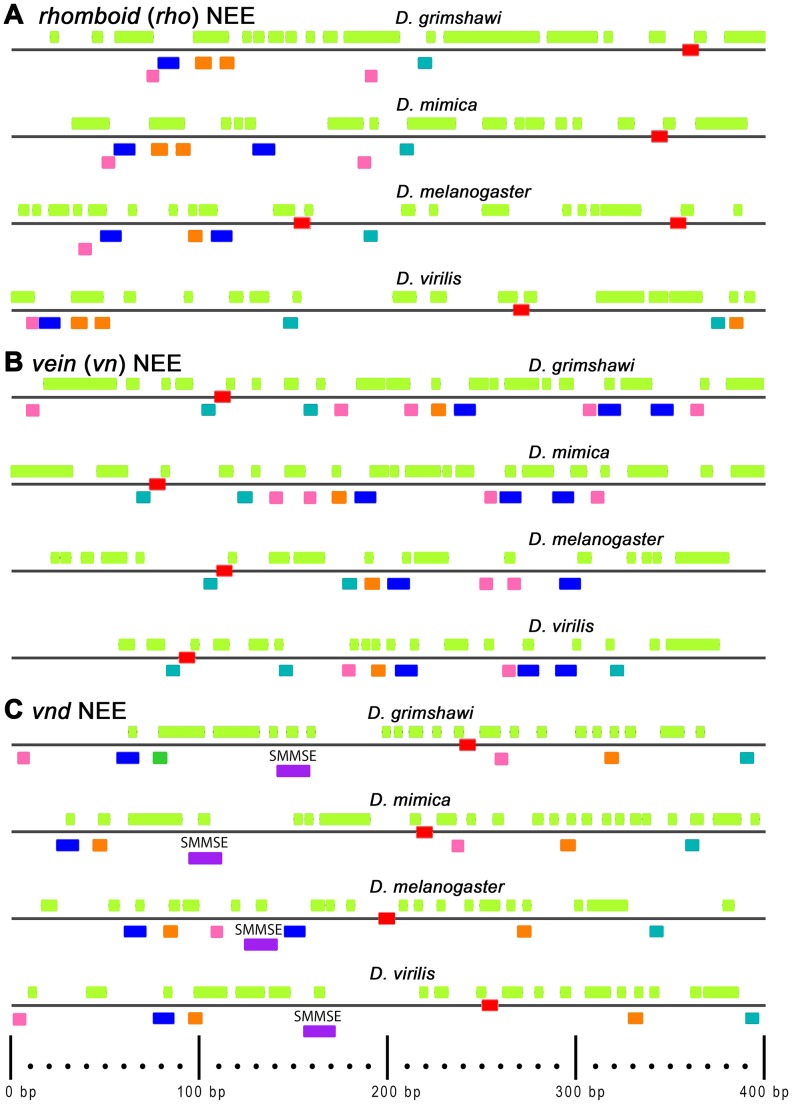

Extensive Microsatellite Repeat (MSR) Replacement of Hawaiian NEE intersite spacers

Inspection of the Hawaiian NEEs reveals diverse microsatellite repeat patterns besides the known genus-wide enrichment of CA-dinucleotide repeats in NEEs [5]. To visualize precisely this content and to determine the possibility of longer repeats being present, we plotted all direct (tail to head) repeats (two or more) of a unit sequence that is 2–50 bp long (fluorescent green boxes in Fig. 3) (also see Materials & Methods). We find that the rho and vn NEEs from both Hawaiian species are qualitatively enriched in MSR content relative to both D. melanogaster and D. virilis (Fig. 3A, B). The enrichment that can be seen in comparison to both non-Hawaiians is made more significant by the fact that D. virilis has a much larger genome than D. melanogaster while also being more closely related to the Hawaiian lineages [4], [5]. The enrichment is not seen in the Hawaiian vnd NEEs relative to the non-Hawaiians (Fig. 3C), but this is as expected for the following two reasons. First, the vnd NEEs are less variable in activity phylogenetically relative to all other NEEs [4]. Second, the vnd NEEs possess a Shnurri:Mad:Medea Silencer Element, which corresponds to a second repressive input from the Dpp morphogen gradient and which ensures its characteristic ventral pattern of expression, critical to its role in patterning the nervous system [19].

Figure 3. Diverse Direct MSRs Fill the Inter-Element Spacers of NEEs from Hawaiian Drosophila.

Graph depicts micro-satelleite repeat (MSR) content, also known as simple sequence repeats, for the NEEs of the Hawaiian species, D. grimshawi and D. mimica, and two non-Hawaiian species, D. virilis and D. melanogaster, which also represent extremes in genome size (large and small, respectively). Note that D. melanogaster is the outgroup species as it is a member of the SOPHOPHORA subgenus. The panels are ordered by orthologous enhancers (rho, vn, vnd) and then by species within each panel, top to bottom. The colored boxes correspond to the same TF binding motifs depicted in Fig. 1 except that the Dorsal Dβ motif is relaxed at one position to 5′-VGGAAABNCCV (underlined “N”) in order to match the site in D. mimica’s NEE at vnd. The MSR content is plotted by a UNIX-type regular expression, “(.{2,50})\1” corresponding to two or more direct repeats of a unit sequence that is at least 2 bp or more in length (green yellow highlight above each line). Many such MSR sequences overlap. While difficult to see at first glance the Hawaiian NEEs are much enriched in this type of content. Exactly 400 bp centered on the NEE heterotypic site cluster is shown.

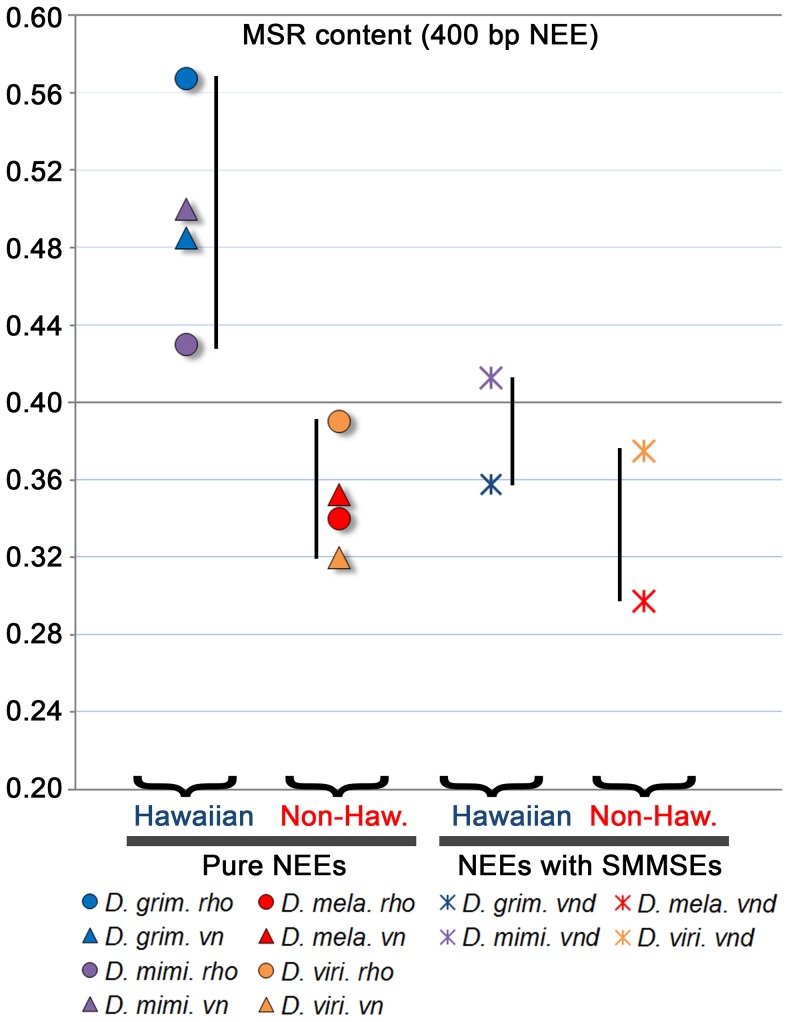

To better quantify the MSR enrichment, we also plotted the exact MSR content for all three of these enhancers across all four species (Fig. 4). This shows that the NEEs without Shnurri/Mad/Medea Silencer Elements (SMMSE [19]) from the Hawaiian species have MSR content in the range of 43–57% in a 400 bp window encompassing all of the relevant TF binding sites (labeled “pure NEEs” in Fig. 4). In comparison, the pure NEEs from the non-Hawaiians have much less content in the range of 32–38%, similar to the range for the vnd NEEs of all species.

Figure 4. Hawaiian NEEs without SMM silencer elements are enriched in MSR content relative to Non-Hawaiians.

Graph plots the MSR content in the 400Figure 3. The points for the “pure” NEEs, which lack Shnurri/Mad/Medea Silence Elements (SMMSE) are plotted separately from the vnd NEE, which contains a highly conserved SMMSE [19]. NEEs for Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians are plotted separately for ease of comparison. The vnd NEE activity is the least variable in output both ontogenetically and phylogenetically [4]. Its highly constrained early ventral expression is fundamentally important for correct D/V patterning of the nervous system and is thus not likely to be subject to shifting selection for a change in stripe width as we previously demonstrated [19]. Assuming that MSR is a signature of previous selection for changes in threshold responses, these results support the view that MSR content is uniquely enriched in enhancers subject to dynamic evolutionary pressures. Note that the length of the SMMSE that is not also MSR-like is 14 bp (19 bp minus 5 bp because of the underlined sequence in the SMMSE motif: 5′-MYGGCGWCACACTGTCTGS.) Thus, the presence of an SMMSE can only account for a reduction of MSR content of no more than 3.5%.

The striking nature of these enhancers can be summarized as follows. The MSR motifs in the rho and vn NEEs of Hawaiians (yellow green tracks in Fig. 3) encompass much of the enhancer, and the remaining sequences are either known TF binding sites (for Dorsal, Twist, Su(H), and Snail), or Zelda sites, which are present generally in early embryonic enhancers but have not been specifically pinpointed in the NEEs [28], [29]. Zelda is considered a pioneer TF for early embryonic activation of genes, whose expression is patterned along the D/V and A/P axes [29]–[31].

We list a few examples of Hawaiian MSR enrichment that illustrate the range of repeat patterns and their phylogenetic distributions. There are many examples of both large and small duplicated blocks conserved only in the Hawaiians (Fig. 5, #1), and some of these have since diverged in repeat number (Fig. 5, #2). In some locations, repeats are found in only one of the Hawaiian species, such as an octamer repeat in the D. grimshawi rho NEE, which is a fragment of the Snail/Zelda sites (Fig. 5, #3). In other locations, repeats are conserved across the genus but the repeat unit sequence differs indicating a potential region of frequently amplified MSR sourced from different sequences prone to repeat slippage (Fig. 5, #4). Last, there are long repeat sequences present in the Hawaiians that are composed of smaller unit repeats (i.e., repeats of repeats; Fig. 5, #5). In many places, the repeats are evidently diverging based on changes to the repeat unit or appearance of indels that disrupt their repeat pattern. Thus, molecular drive based on MSR slippage is an important mechanism in NEE evolution at the rho and vn loci of Hawaiian lineages but its subdued presence in the constrained vnd NEEs suggests that natural selection continuously acts on this mutagenic source of functional variation [32].

Figure 5. The non-Dpp constrained NEEs at rho and vein are rapidly diverging via MSR mutagenesis in the Hawaiian lineages.

Shown is a sequence alignment for the vn (top) and rho (bottom) NEEs highlighted to show MSR content (green letters with squiggly underline). The motif coloring follows previous figures. Due to multiple insertions and deletions, these homologous sequences depicted are of different lengths. Numbers indicate the presence of novel MSR sequences present only in Hawaiians (the octapeptide 2x repeat at #1), present only in Hawaiians but still diverging (5 to 13 repeats of CA-microsatellite at #2), sites of MSR repeats of different types at the same position and present only in the DROSOPHILA subgenus (#3) or across the entire genus (#4), and repeats of made of smaller repeats and seen only in Hawaiian species (#5). In addition, other divergent repeat content that is not highlighted by the strict MSR algorithm can also be seen (see Material & Methods).

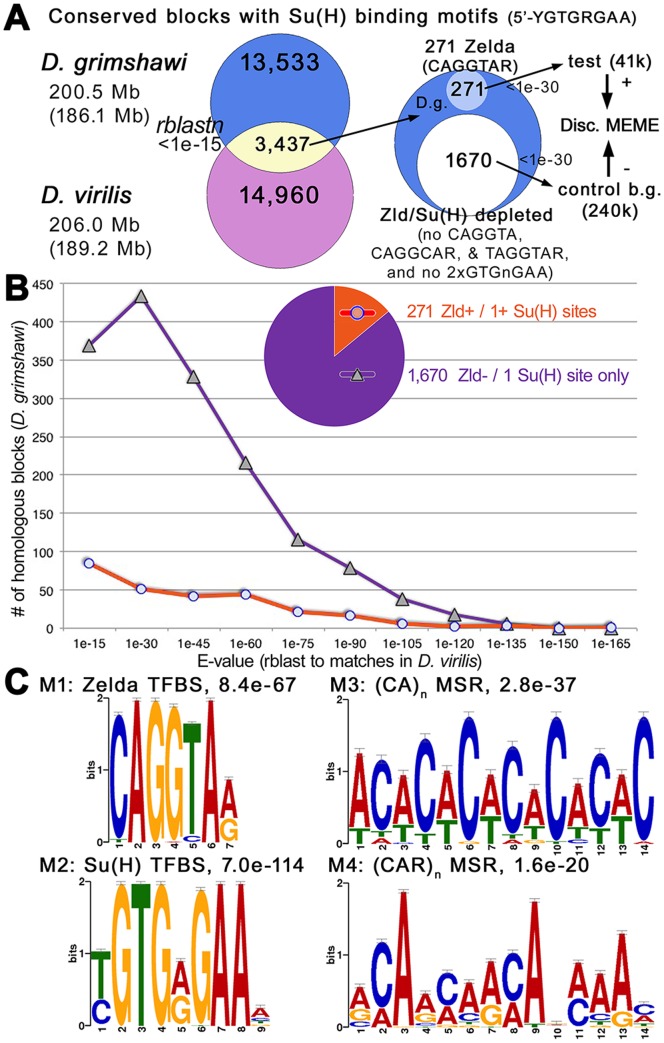

MSR-Enrichment in Embryonic vs. Non-embryonic Notch-Target Enhancers in D. grimshawi

The extreme MSR-footprint is widespread in the Hawaiian NEEs and here we demonstrate that in general the embryonic enhancers from Hawaiian Drosophila are enriched for MSR using two different genome-wide analyses described below. We first asked whether this MSR-enrichment was a general property of Notch-target, Su(H) binding site containing enhancers or only a specific feature of embryonic enhancers targeted by Notch/Su(H). To do this, we undertook an analysis of the entire set of Su(H) binding repertoire for D. virilis and D. grimshawi. We first identified all individual Su(H) sites (5′-YGTGRGAA) and/or clusters of sites in each of the two genomes. This dataset was composed of blocks containing up to 270 bp of sequence flanking the Su(H) site or site cluster when possible, but ∼3% of sequences had less because of close proximity to the edge of a contig but were not eliminated (385/13,473 and 476/14,904 for D. grimshawi and D. virilis, respectively). Site clusters were defined as having at least two Su(H)-binding sequences separated by <540 bp (i.e., less than twice the desired flanking distance of 270 bp). Site clusters defined 6.0% of the data for D. grimshawi (815/13,473), and 7.1% of the data for D. virilis (1,060/14,904).

In order to identify conserved blocks between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian Su(H)-binding motif containing repertoires, we identified sequence alignment parameters that are suited for the patterns of indel/MSR-mediated divergence that we see in Drosophila enhancers. We took a heuristic approach to settle on a set of customized regulatory “rblastn” parameters that gave the highest alignment scores to NEEs that are homologous to each other across different Drosophila species (see Methods). Using this rblastn pipeline and an E-value cutoff of <1.0e-15, we identified ∼3400 homologous sequences between D. grimshawi and D. virilis, which includes the canonical NEEs present across the genus at four unrelated loci: rho, vn, brk, and vnd [4], [5], [19]–[21].

We then took these ∼3400 sequences from D. grimshawi and split them into two distinct sets (Fig. 6A). The first set of 270 sequences were identified because they had perfect binding sites for the embryonic temporal activator Zelda (5′-CAGGTAR), a pioneer TF for early gene activation [29]–[31]. As seen in the sequence alignments between the two Hawaiians and other Drosophila genomes, Zelda binding sites (Fig. 5 E, F, cyan nucleotides) are readily apparent between diverse MSR signatures (yellow green sequences in Fig. 5). The second set of 1671 sequences was derived by depleting the set of ∼3400 conserved blocks of those blocks containing either Zelda binding sequences (5′-CAGGTA, 5′-CAGGCAR, or 5′-TAGGTAR), or more than a single Su(H) binding site (5′-nGTGnGAAn). To ensure that our test and control data sets contained sequences with equivalent levels of conservation, we plotted the distribution of E-values and found that there are still proportionally many highly conserved sequences in both data sets (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Microsatellite Repeats are Enriched in Conserved Su(H) Site-Containing D. grimshawi DNAs of Embryonic Enhancers Relative to Non-Embryonic Enhancers.

(A) Shown is a flowchart of Venn diagrams showing the identification of 3,437 conserved blocks containing Su(H) sites in D. grimshawi and D. virilis with regulatory blastn (“rblastn”) E-value of <1e-15 using parameters calibrated to the NEEs. Homologous sequences from D. grimshawi were separated into test and control data sets for discriminative motif elicitation by maximum expectation (MEME) [33]. The test data set of 271 sequences contains Zelda sites (5′-CAGGTAR). The negative control set of 1,670 sequences is depleted of blocks containing any Zelda site (5′-CAGGTA, 5′-CAGGCAR, and 5′-TAGGTAR) or more than a single Su(H) binding sequence (5′-GTGnGAA). (B) The distribution of E-values for rblastn hits of the Su(H) strings shows that the test data set of conserved blocks containing Zelda sites are not any less conserved than the control data set lacking these sites. (C) MEME analysis identifies CA-dinucleotide and CAR-trinucleotide MSR motifs as being enriched in the Zelda+ dataset relative to other Su(H)-containing conserved blocks.

We find that the Zelda-positive data set contains much more (CA)n- and (CAR)n- MSR content than the control data set using a discriminative MEME [33] analysis (Fig. 6C). (CA)n-MSR is known to be highly enriched in NEEs, and even enriched in D. virilis relative to D. melanogaster, which has a smaller genome [5]. As CAG-trinucleotide repeats and repeat instabilities are often seen in the protein-coding sequences for many transcriptional activators [34]–[37], we asked whether the enrichment of this motif was possibly due to the occurrence of nearby protein-coding exons near intronic enhancers. We find that almost all of the (CAR)n-MSR content contributing to the enrichment occurs in non-protein-coding sequence (see File S3 and Table S1).

In sum, these findings suggest first that Notch-target enhancers that are operative in the early embryo are more divergent (and hence potentially faster-evolving) than non-embryonic enhancers containing Su(H)-binding sequences, and second that the divergence is driven in part by a molecular drive mechanism that changes the internal spacing separating TF binding sites. In the Discussion, we propose some molecular phenotypes that could explain why natural selection would act on the prodigious output of this MSR drive mechanism.

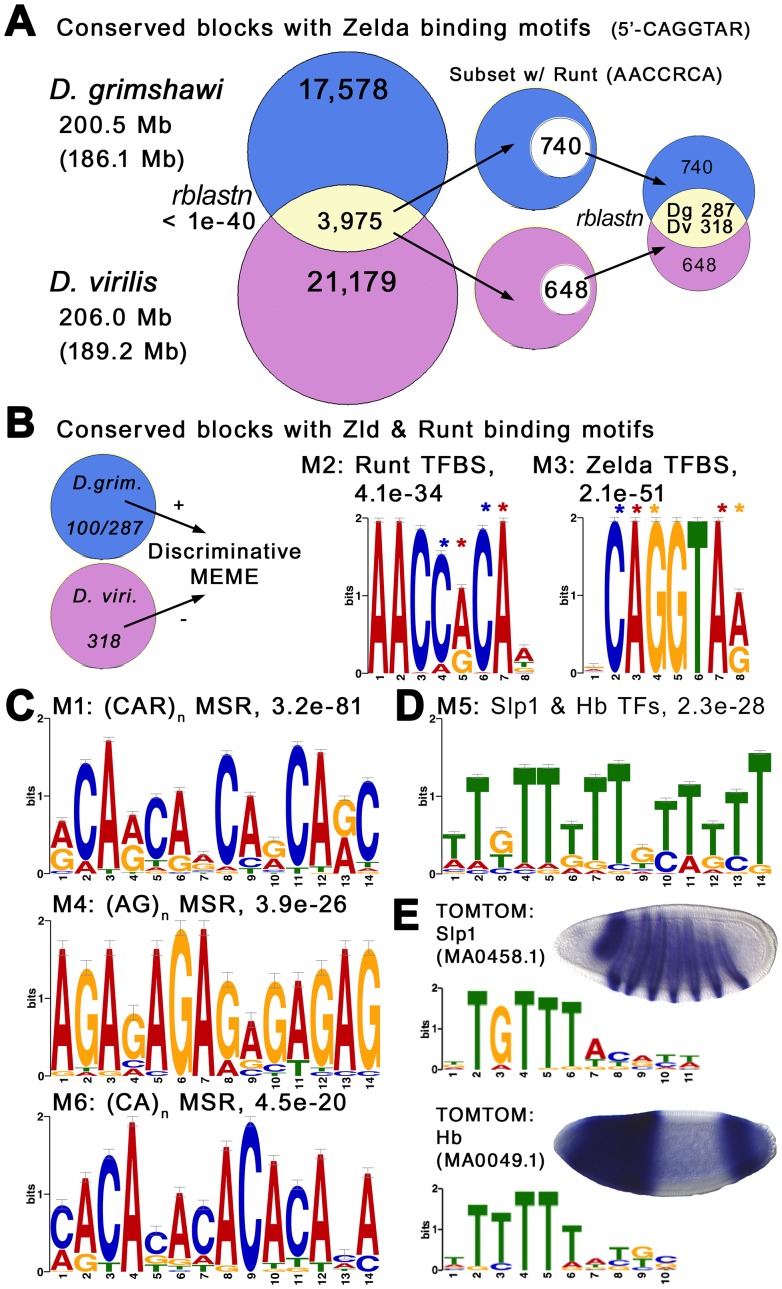

MSR-Enrichment in A/P Embryonic Enhancers of Hawaiian vs. Non-Hawaiian Drosophila

To determine whether unique MSR signatures are also enriched in embryonic, anterior/posterior (A/P) patterned enhancers, we first identified 3975 conserved blocks containing Zelda binding sites in D. grimshawi and D. virilis, with rblastn E-values of less than 1.0e-40 (Fig. 7A). From these we chose the subset of sequences that also contain a binding site for Runt (5′-AACCRCA), which represses the posterior expression domains of Bcd targets in the intermediate regions of the Bcd morphogen gradient [38]. Unlike the Bcd binding motif, the Runt binding motif is better suited to our question because it is: (i) well-defined [38], (ii) less variable, (iii) not related to binding sites for a large family of TFs such as the homeodomain-containing TFs, and (iv) associated with enhancers reading the rate-limiting parts of the Bcd morphogen gradient [38]. Because Runt binding sites were not always found in homologous sequences (either for lack of conservation or due to location of a truncated block near the edge of a contig), we performed a second rblastn query to identify only those with reciprocal homologs (Fig. 5A). We then performed a discriminative MEME analysis [33] using the set of homologous Zelda+Runt-containing sequences from D. grimshawi and D. virilis as the positive and negative data sets, respectively.

Figure 7. Diverse MSR Motifs are Enriched in the Embryonic A/P Patterning Enhancers of D. grimshawi Relative to their Homologous Sequences in D. virilis.

(A) Shown is a flowchart of Venn diagrams showing the identification of 3,975 conserved blocks containing Zelda binding sites in D. grimshawi and D. virilis with an rblastn E-value of <1e-40. From these were chosen those that also contain a binding site for Runt (5′-AACCRCA), which is known to repress the posterior expression domains of targets induced by intermediate levels of the Bcd morphogen gradient. Because the Runt binding sites are not always found in the homologous sequences (either for lack of conservation or due to flanking truncation of the blocks), a second rblastn is performed to identify only the ones with reciprocal homologs. (B) A discriminative MEME analysis identifies the binding sites for Runt and Zelda relative in D. grimshawi vs. D. virilis, likely due to increased homotypic site clustering of these sites as well as (C) diverse MSR motifs, and (D) a motif matching binding sites for the pair-rule and gap products Slp1 and Hb. Numbers within each circle in (B) represent number of sequences used in MEME analysis due to constraints on test set (100 random sequences for D. grimshawi) versus control data set (entire data set or 318 sequences for D. virilis). Asterisks in (B) indicate di- and tri-nucleotide patterns found in the MSRs. (E) TOMTOM results showing matches to motif M5, and expression of slp1 and hb in early embryo.

We find that the binding sites for Runt and Zelda are enriched in D. grimshawi relative to D. virilis (Fig. 7B), and suspect this is likely due to increased homotypic site clustering of these sites [39]. This is consistent with higher rates of binding site turnover, and we hope to investigate this matter in later studies. We also identified diverse MSR motifs, including the (CA)n-dinucleotide and (CAR)n-trinucleotide motifs previously seen in the embryonic Su(H) data set (Fig. 7C). We note that the binding motifs for both Zelda and Runt contain fragments of these sequences (asterisks in Fig. 7B). We also identify a clear (AG)n-dinucleotide MSR motif (Fig. 7C), which best matches the binding site for Trithorax-like (Trl), which encodes the GAGA-binding factor GAGA that is expressed ubiquitously in the early embryo [40]. Thus, Zelda, Runt, and GAGA may be natural sources of functionally variant spacer alleles, much like the Twist-binding site of the NEEs [19]. This further supports our previously proposed hypothesis [5] that MSR-enrichment of enhanceosome-building enhancers is related to the intrinsic MSR-seeding capabilities of Activator TF binding sites. Last, we identify a T-rich motif, which is likely to also serve as a source of mono-nucleotide runs (Fig. 7D). We find that this motif best matches binding sites for the pair-rule and gap products Slp1 and Hb, consistent with their expression patterns (Fig. 7E). This is also consistent with Zelda’s role in early embryonic timing of gene activation, and Runt’s role in repressing the posterior borders of expression of Bcd targets in the central region of the embryo.

Discussion

A Model for How Certain Classes of Enhanceosome Scaffold Result in MSR-Enrichment

Previous analyses of Drosophila genomic sequences have demonstrated a non-random distribution of microsatellite repeat (MSR) sequences in Drosophila genomes [41]–[43], the presence of compound (i.e., clustered) MSR tracts [44], and an unpredicted excess of long MSR sequences [45]. It was also previously shown that the length of a spacer DNA separating linked Dorsal and Twist activator binding sites sites in the Neurogenic Ectoderm Enhancers (NEEs) can play a functional role [4]. It was then subsequently shown that CA-dinucleotide MSR related to the Twist site is used to source functional variants during evolution [5]. Here, we show that the Hawaiian NEEs offer an extreme case of MSR enrichment in terms of both the amounts and types of MSR content. These observations hint at additional spacer functionalities at other sites within the NEEs, the extent of functionality of which will have to be tested with additional mutagenesis in transgenic reporter assays.

Our results show that MSR-enrichment patterns can be linked to entire classes of regulatory DNAs, which in this case correspond to embryonic enhancer DNAs driven by the A/P and D/V morphogens patterning the syncytial embryo. Specifically, we showed that intervening DNA sequences between the Hawaiian Drosophila NEE binding sites have been replaced by microsatellite repeat (MSR) sequences and that these MSR sequences are still diverging. We showed that MSR demarcates the majority of the spaces separating the functional binding sites for Dorsal (i.e., the Dβ site), Twist/Snail [i.e., the E(CA)T site], Su(H), as well as the dedicated [non-E(CA)T] Snail binding sites, and sites for the general embryonic timing factor Zelda. Our use of footprinting to describe this effect of MSR enrichment in Hawaiian embryonic enhancers is in line with both phylogenetic footprinting and enzymatic footprinting. In MSR footprinting, phylogenetic footprinting, and enzymatic footprinting, the principle means used to reveal TF binding sites are by highlighting the space separating the sites via MSR content, divergence, and digestibility, respectively.

We also showed that the subset of conserved Su(H) site-containing Hawaiian blocks that contain binding sites for Zelda are specifically enriched in MSR motifs relative to non-Zelda containing conserved blocks from the same species, and that there was similar enrichment of MSR motifs in this set of Runt+Zelda containing blocks in the Hawaiian D. grimshawi relative to their homologous sequences in D. virilis. These results demonstrate that embryonic enhancers from Hawaiian Drosophila are enriched in MSR relative to both (i) other equally-conserved developmental enhancers from Hawaiian Drosophila, and (ii) homologous embryonic enhancers from non-Hawaiian Drosophila.

We propose that: (i) transcription factor activator complexes are sensitive to the spacing of Activator TF binding sites within enhancers that serve as assembly scaffolds for the aggregation of such complexes; and (ii) MSR enrichment in embryonic enhancers is a signature of frequent past selection for as yet unknown complex characteristics (e.g., rate of assembly, complex stability on DNA, complex off-rate, and non-DNA bound complex half-life after assembly). As most indels are produced by microsatellite repeat slippage, enhancers from Hawaiian Drosophila lineages that are subjected to frequent evolutionary pressures would become grossly enriched in MSR content. Furthermore, as the embryonic enhancers would be subject to tremendously dynamic evolutionary pressures associated with both life cycle and ecological contexts affecting egg size, egg shape, and embryonic development during adaptive radiations, they would be more enriched in MSR signatures than enhancers operating at later developmental stages. While Drosophila lineages in general have exhibited much divergence related to adult pigmentation (e.g., wing spot patterning), adult behavior (e.g., mate choice and courtship song), and potentially other adult systems [46]–[52], we are unable to identify bioinformatically the enhancer sequences underlying these specific systems selectively without also pulling out many other non-changing adult enhancers. Thus, it is possible that the MSR enrichment we have seen for embryonic enhancers relative to all non-embryonic enhancers could be comparable to a select subset of enhancers underlying dynamically evolving adult phenotypes. Recent studies have indicated the utility of such MSR signatures for enhancer class identification [5], [53].

The genetics of microsatellite repeat number has received much attention also because of the role played by CAR-trinucleotide expansions in many neurodegenerative disorders and this has been extended to Drosophila [54]. In a study of length variation and evolution of CAR-trinucleotide microsatellite, or rather their “extreme conservation” in the Drosophila gene mastermind (mam) gene it was suggested that there must be strong selective constraints acting on the spacer lengths [36]. In a test of the null hypothesis that such length divergence arose by chance led to the conclusion that the CAR-MSR content in mam evolves both by molecular drive due to frequent repeat slippage and by natural selection on optimal spacer lengths [37]. Sequence data on de novo mutations from the HapMap project has also established that MSR-instability is repeat length dependent because similar instabilities are seen across diverse repeat unit sizes and sequences [34]. As we have previously shown the importance of CA-microsatellite repeat slippage emanating from the CA-dinucleotide rich Twist binding site in the NEEs [5], we conclude that MSR repeat variants are generally sourced by selection to adjust functional spacers across both cis-regulatory and protein-coding components of a genome. Thus, routine methods in bioinformatics, such as genomic repeat filtering and genome assembly based on point differences relative to a reference genome (as opposed to de novo assembly), may filter out important MSR-based functional variation that differentiates closely related genomes.

Methods

Bioinformatics

UNIX-shell scripts were written using grep, perl, and the BASH command set to identify all Su(H) sites and site clusters in the genome assemblies of D. grimshawi (r1.3) and D. virilis (r1.2) (see File S1). Site clusters were defined as two or more Su(H) sites located less than twice the desired flanking distance. For Su(H) binding sites (5′-YGTGRGAA) this was defined as 292 bp because (292 bp×2 flanking sequences) +8 bp = 600 bp. For Zelda (5′-CAGGTAR) we defined blocks as +/−300 bp from the Zelda binding site. The special case of not having enough flanking sequence due to proximity to the edge of a contig was also handled and these sequences kept in the data sets. For blastn analyses, the UNIX command line version of blast tools was downloaded from NCBI. The parameter set used for Drosophila enhancer bioinformatics identified largely by trial and error is the following: “-penalty −4 -reward 5 -word_size 9 -gapopen 8 -gapextend 6 -xdrop_gap_final 90 -best_hit_overhang 0.25 -best_hit_score_edge 0.1”. The subset of conserved Su(H) blocks with linked Twist–Dorsal sites (5′-CACATGT 0–41 bp GGAAABYCC) were identified with the UNIX-style regular expression: “CACATGT.{0,41}GGAAA[∧A][CT]CC”. All shell scripts are provided in File S1.

MEME analyses

We performed discriminative motif discovery using Multiple EM for motif elicitation (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/) and a control data set of negative sequences, and searched for “zero or one” occurrences per sequence [33]. We specified motif limits of 6 to 14 bp, and asked for an optimum number of sites between 10 and 300 with the upper limit varying depending on the size of the test data set, usually setting it at a maximum of 1.5x the number of sequences. For control data set we chose to use the maximum allowed dataset size of 240,000 characters. For the test data set limit of 60,000 characters we would choose a random sample if the data set was larger. For example, in the analysis depicted in Figure 7, we used 100 random sequences out of the 287 sequences available due to constraints on test data set.

In situ hybridization

Whole-mount anti-sense in situ hybridizations with a digoxigenin UTP-labeled anti-sense RNA probe against lacZ were conducted on fixed embryos collected over a four hour egg-laying period held at room temperature. NEE reporters were integrated into the P-element vector between the mini-white gene and −42 eve:lacZ reporter as previously described [55].

Molecular cloning

Live D. mimica were obtained from the UCSD stock center and reared with a protocol similar to that supplied from the stock center. Genomic DNA for PCR amplification was prepared using the Ashburner protocol [56], except that three adult flies instead of a single one were homogenized in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Homogenization buffer, lysis buffer, and 8 M K acetate were used as described, followed by phenol-CHCl3 extractions, and EtOH precipitation. A 626 bp fragment of the rho NEE from D. mimica was cloned using the following oligonucleotide primers based on the D. grimshawi reference genome: 5′-AGA TGA AAA TCC GCA ATG CAA CGG (top strand primer), and 5′-AAA CAC AGC AGA AAG TCT CAA GC (bottom strand primer). A 513 bp fragment of the vn NEE from D. mimica was cloned and sequenced using the following oligonucleotide primers based on the D. grimshawi reference genome: 5′-ACA GAA GCT CAG CAT TTG GC (top strand primer), and 5′- GCC AGC GGC AAT TTT ATC TGC (bottom strand primer). A ∼500 bp fragment of the vnd NEE from D. mimica was cloned and sequenced using the following oligonucleotide primers based on the D. grimshawi reference genome: 5′-CCA CCG GGT CTC AAA TTC TTT CAC AGT (top strand primer), and 5′-CCA CCG GGT CTC AAA TTC CCA TCA ACA (bottom strand primer). These amplified PCR fragments were cloned into Promega’s pGEM-T easy cloning vector. Clones were sequenced, and a few were selected to be cut with EcoR I, gel purified, and ligated into the EcoR I-cut pCaspeR P-element vector carrying the −42 eve lacZ-tubulin 3′UTR reporter construct previously reported [4], [5]. The cloned enhancers from D. mimica have been deposited at GenBank and have accession numbers: KJ814003 (Dmim_rhomboid_NEE), KJ814004 (Dmim_vein_NEE), and KJ814005 (Dmim_vnd_NEE). In addition, the sequences for the NEEs of both Hawaiian Drosophila species are included in File S2.

Supporting Information

Location of CAR repeat-rich sequences in conserved Su(H) blocks.

(PDF)

Unix computer scripts.

(TGZ)

FASTA file of D. mimica and D. grimshawi enhancer sequences.

(TXT)

Annotated Su(H) blocks from D. grimshawi (Zelda+) with (CAR)n repeats.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Fassler, Gary Gussin, Clinton Rice, and Danielle Beekman for reading and commenting on our manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. New enhancer DNA sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank and the accession number added to the manuscript. Supporting Information includes files for computer scripts, DNA sequences, and other supplementary information.

Funding Statement

AE: National Science Foundation, Award: 1239673. ES: National Institutes of Health, Training Grant: T32GM082729. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Drosophila 12 Genomes C, Clark AG, Eisen MB, Smith DR, Bergman CM, et al (2007) Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature 450: 203–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huntley MA, Clark AG (2007) Evolutionary analysis of amino acid repeats across the genomes of 12 Drosophila species. Mol Biol Evol 24: 2598–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhutkar A, Schaeffer SW, Russo SM, Xu M, Smith TF, et al. (2008) Chromosomal rearrangement inferred from comparisons of 12 Drosophila genomes. Genetics 179: 1657–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crocker J, Tamori Y, Erives A (2008) Evolution acts on enhancer organization to fine-tune gradient threshold readouts. PLoS Biol 6: e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crocker J, Potter N, Erives A (2010) Dynamic evolution of precise regulatory encodings creates the clustered site signature of enhancers. Nat Commun 1: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roy S, Ernst J, Kharchenko PV, Kheradpour P, Negre N, et al. (2010) Identification of functional elements and regulatory circuits by Drosophila modENCODE. Science 330: 1787–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carson HL, Clayton FE, Stalker HD (1967) Karyotypic stability and speciation in Hawaiian Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 57: 1280–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carson HL (1973) Ancient chromosomal polymorphism in Hawaiian Drosophila. Nature 241: 200–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carson HL (1982) Evolution of Drosophila on the newer Hawaiian volcanoes. Heredity (Edinb) 48: 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carson HL (1983) Chromosomal sequences and interisland colonizations in hawaiian Drosophila. Genetics 103: 465–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ayala FJ, Campbell CD, Selander RK (1996) Molecular population genetics of the alcohol dehydrogenase locus in the Hawaiian drosophilid D. mimica. Mol Biol Evol 13: 1363–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carson HL (1997) The Wilhelmine E. Key 1996 Invitational Lecture. Sexual selection: a driver of genetic change in Hawaiian Drosophila. J Hered 88: 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carson HL (2002) Female choice in Drosophila: evidence from Hawaii and implications for evolutionary biology. Genetica 116: 383–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Grady PM, Kam MWY, Val FC, Perreira WD (2003) Revision of the Drosophila mimica subgroup, with descriptions of ten new species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 96: 12–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edwards KA, Doescher LT, Kaneshiro KY, Yamamoto D (2007) A database of wing diversity in the Hawaiian Drosophila. PLoS One 2: e487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell JR (1997) Progress and prospects in evolutionary biology : the Drosophila model. New York: Oxford University Press. xiv, 562 p.

- 17.Kambysellis MP, Heed WB (1971) Studies of Oogenesis in Natural Populations of Drosophilidae.1. Relation of Ovarian Development and Ecological Habitats of Hawaiian Species. American Naturalist 105: 31–&.

- 18. Kambysellis MP, Starmer T, Smathers G, Heed WB (1980) Studies of Oogenesis in Natural-Populations of Drosophilidae.2. Significance of Microclimatic Changes on Oogenesis of Drosophila-Mimica. American Naturalist 115: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crocker J, Erives A (2013) A Schnurri/Mad/Medea complex attenuates the dorsal-twist gradient readout at vnd. Dev Biol 378: 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erives A, Levine M (2004) Coordinate enhancers share common organizational features in the Drosophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 3851–3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crocker J, Erives A (2008) A closer look at the eve stripe 2 enhancers of Drosophila and Themira. PLoS Genet 4: e1000276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stathopoulos A, Levine M (2004) Whole-genome analysis of Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14: 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barolo S (2012) Shadow enhancers: frequently asked questions about distributed cis-regulatory information and enhancer redundancy. Bioessays 34: 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frankel N, Davis GK, Vargas D, Wang S, Payre F, et al. (2010) Phenotypic robustness conferred by apparently redundant transcriptional enhancers. Nature 466: 490–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hong JW, Hendrix DA, Levine MS (2008) Shadow enhancers as a source of evolutionary novelty. Science 321: 1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perry MW, Boettiger AN, Bothma JP, Levine M (2010) Shadow enhancers foster robustness of Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Biol 20: 1562–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanodia JS, Rikhy R, Kim Y, Lund VK, DeLotto R, et al. (2009) Dynamics of the Dorsal morphogen gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 21707–21712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harrison MM, Botchan MR, Cline TW (2010) Grainyhead and Zelda compete for binding to the promoters of the earliest-expressed Drosophila genes. Dev Biol 345: 248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang HL, Nien CY, Liu HY, Metzstein MM, Kirov N, et al. (2008) The zinc-finger protein Zelda is a key activator of the early zygotic genome in Drosophila. Nature 456: 400–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harrison MM, Li XY, Kaplan T, Botchan MR, Eisen MB (2011) Zelda binding in the early Drosophila melanogaster embryo marks regions subsequently activated at the maternal-to-zygotic transition. PLoS Genet 7: e1002266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nien CY, Liang HL, Butcher S, Sun Y, Fu S, et al. (2011) Temporal coordination of gene networks by Zelda in the early Drosophila embryo. PLoS Genet 7: e1002339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dover G (1982) Molecular drive: a cohesive mode of species evolution. Nature 299: 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, et al. (2009) MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res 37: W202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ananda G, Walsh E, Jacob KD, Krasilnikova M, Eckert KA, et al. (2013) Distinct mutational behaviors differentiate short tandem repeats from microsatellites in the human genome. Genome Biol Evol 5: 606–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ashley CT Jr, Warren ST (1995) Trinucleotide repeat expansion and human disease. Annu Rev Genet 29: 703–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newfeld SJ, Schmid AT, Yedvobnick B (1993) Homopolymer length variation in the Drosophila gene mastermind. J Mol Evol 37: 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Newfeld SJ, Tachida H, Yedvobnick B (1994) Drive-selection equilibrium: homopolymer evolution in the Drosophila gene mastermind. J Mol Evol 38: 637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen H, Xu Z, Mei C, Yu D, Small S (2012) A system of repressor gradients spatially organizes the boundaries of Bicoid-dependent target genes. Cell 149: 618–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li L, Zhu Q, He X, Sinha S, Halfon MS (2007) Large-scale analysis of transcriptional cis-regulatory modules reveals both common features and distinct subclasses. Genome Biol 8: R101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhat KM, Farkas G, Karch F, Gyurkovics H, Gausz J, et al. (1996) The GAGA factor is required in the early Drosophila embryo not only for transcriptional regulation but also for nuclear division. Development 122: 1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harr B, Zangerl B, Brem G, Schlotterer C (1998) Conservation of locus-specific microsatellite variability across species: a comparison of two Drosophila sibling species, D. melanogaster and D. simulans. Mol Biol Evol 15: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bachtrog D, Weiss S, Zangerl B, Brem G, Schlotterer C (1999) Distribution of dinucleotide microsatellites in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Mol Biol Evol 16: 602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bachtrog D, Agis M, Imhof M, Schlotterer C (2000) Microsatellite variability differs between dinucleotide repeat motifs-evidence from Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol 17: 1277–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kofler R, Schlotterer C, Luschutzky E, Lelley T (2008) Survey of microsatellite clustering in eight fully sequenced species sheds light on the origin of compound microsatellites. BMC Genomics 9: 612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dieringer D, Schlotterer C (2003) Two distinct modes of microsatellite mutation processes: evidence from the complete genomic sequences of nine species. Genome Res 13: 2242–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cooley AM, Shefner L, McLaughlin WN, Stewart EE, Wittkopp PJ (2012) The ontogeny of color: developmental origins of divergent pigmentation in Drosophila americana and D. novamexicana. Evol Dev 14: 317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gompel N, Prud’homme B, Wittkopp PJ, Kassner VA, Carroll SB (2005) Chance caught on the wing: cis-regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature 433: 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wittkopp PJ, Carroll SB, Kopp A (2003) Evolution in black and white: genetic control of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Trends Genet 19: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wittkopp PJ, Williams BL, Selegue JE, Carroll SB (2003) Drosophila pigmentation evolution: divergent genotypes underlying convergent phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 1808–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shirangi TR, Stern DL, Truman JW (2013) Motor control of Drosophila courtship song. Cell Rep 5: 678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arthur BJ, Sunayama-Morita T, Coen P, Murthy M, Stern DL (2013) Multi-channel acoustic recording and automated analysis of Drosophila courtship songs. BMC Biol 11: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cande J, Andolfatto P, Prud’homme B, Stern DL, Gompel N (2012) Evolution of multiple additive loci caused divergence between Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea in wing rowing during male courtship. PLoS One 7: e43888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanez-Cuna JO, Arnold CD, Stampfel G, Boryn LM, Gerlach D, et al. (2014) Dissection of thousands of cell type-specific enhancers identifies dinucleotide repeat motifs as general enhancer features. Genome Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54. Jung J, van Jaarsveld MT, Shieh SY, Xu K, Bonini NM (2011) Defining genetic factors that modulate intergenerational CAG repeat instability in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 187: 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Erives A, Corbo JC, Levine M (1998) Lineage-specific regulation of the Ciona snail gene in the embryonic mesoderm and neuroectoderm. Dev Biol 194: 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sullivan W, Ashburner M, Hawley RS (2000) Drosophila protocols. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. xiv, 697 p. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ip YT, Park RE, Kosman D, Bier E, Levine M (1992) The dorsal gradient morphogen regulates stripes of rhomboid expression in the presumptive neuroectoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev 6: 1728–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Location of CAR repeat-rich sequences in conserved Su(H) blocks.

(PDF)

Unix computer scripts.

(TGZ)

FASTA file of D. mimica and D. grimshawi enhancer sequences.

(TXT)

Annotated Su(H) blocks from D. grimshawi (Zelda+) with (CAR)n repeats.

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. New enhancer DNA sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank and the accession number added to the manuscript. Supporting Information includes files for computer scripts, DNA sequences, and other supplementary information.