ABSTRACT

E-cadherin (CDH1) is a cell adhesion molecule that coordinates key morphogenetic processes regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. Loss of CDH1 is a trademark of the cellular event epithelial to mesenchymal transition, which increases the metastatic potential of malignant cells. PTEN is a tumor-suppressor gene commonly mutated in many human cancers, including endometrial cancer. In the mouse uterus, ablation of Pten induces epithelial hyperplasia, leading to endometrial carcinomas. However, loss of Pten alone does not affect longevity until around 5 mo. Similarly, conditional ablation of Cdh1 alone does not predispose mice to cancer. In this study, we characterized the impact of dual Cdh1 and Pten ablation (Cdh1d/d Ptend/d) in the mouse uterus. We observed that Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice died at Postnatal Days 15–19 with massive blood loss. Their uteri were abnormally structured with curly horns, disorganized epithelial structure, and increased cell proliferation. Co-immunostaining of KRT8 and ACTA2 showed invasion of epithelial cells into the myometrium. Further, the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice had prevalent vascularization in both the endometrium and myometrium. We also observed reduced expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors, loss of cell adherens, and tight junction molecules (CTNNB1 and claudin), as well as activation of AKT in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. However, complex hyperplasia was not found in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. Collectively, these findings suggest that ablation of Pten with Cdh1 in the uterus accelerates cellular invasiveness and angiogenesis and causes early death.

Keywords: angiogenesis and dissemination, CDH1, invasion, PTEN, uterus

Ablation of Cdh1 with Pten in the mouse uterus accelerates cellular invasiveness and angiogenesis, and is fatal during early life.

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common malignancy of the female genital tract, affecting over 47 000 women and leading to approximately 8000 deaths in the United States each year [1]. While overall survival is relatively high for patients identified with early-stage disease, aggressive phenotypes of endometrial carcinomas do exist, and women unfortunate enough to develop them exhibit high recurrence after initial treatment and low survival rates. Several treatment options, such as hysterectomy, hormonal therapy, and combinations of radiation and chemotherapy, are effective for early-stage endometrial carcinomas; however, only limited options remain if the tumors metastasize [2]. Furthermore, effective target therapies, especially for the patients with metastatic or recurrent endometrial cancer, are unavailable because the etiology and biological mechanisms of this heterogeneous disease are not fully understood. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the etiology of endometrial tumorigenesis and metastasis in order to formulate novel treatment strategies that lead to remission and increase long-term survival.

PTEN mutations are observed in >50% of endometrial carcinomas [2–4]. Specifically, recent studies reported that loss of PTEN in epithelial cells is a critical event for endometrial tumorigenesis [5, 6]. PTEN is a major negative regulator of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, which regulates a number of cellular functions via activation of AKT [7, 8]. Thus, abnormal epithelial-specific activation of PI3K/AKT signaling initiates endometrial carcinomas [6, 9]. Mouse models harboring conditionally deleted Pten in the uterus using PgrCre/+ mice induces epithelial hyperplasia as young as Postnatal Day 10 [5]. Hyperplasia further progresses to carcinomas, with invasion into the myometrium occurring by 3 mo of age [5]. However, these mice have never displayed distant metastasis to any other organs. Even though some tumor cells may disseminate into the peritoneum, these mice start dying from growing primary tumors ([5] and Hayashi, unpublished observation).

E-cadherin (CDH1), a transmembrane glycoprotein, belongs to the cadherin superfamily of cell adhesion molecules [10]. In epithelial tissues, interactions between neighboring cells are mainly mediated by cadherins to establish and maintain cell polarity and the epithelial phenotype [11]. CDH1 is often downregulated or lost during tumor progression [12–15], leading to increased tumor invasiveness and metastasis [16–21]. We recently reported [22] that conditional ablation of Cdh1 in the mouse uterus results in a disorganized cellular structure of the epithelium and ablation of endometrial glands. These mice are also infertile due to defects during implantation and decidualization. However, loss of Cdh1 alone in the uterus does not predispose mice to tumors [22]. Outside the uterus, conditional ablation of Cdh1 does not induce any tumors in mammary glands [23–25] or stomach [26]. Thus, these results indicate that single gene ablation in the uterus is not sufficient to understand the etiology of heterogeneous, aggressive types of endometrial carcinomas.

In the present study, we generated a mouse model in which Pten and Cdh1 were conditionally ablated in the uterus. Specifically, we investigated whether ablation of Pten and one of the critical invasive regulators, Cdh1, accelerates endometrial neoplastic transformation and induces cell invasion and dissemination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Tissue Collection

Mice were maintained in the vivarium at Southern Illinois University according to the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. B6.129-Pgrtm2 (cre)Lyd (i.e., Pgrcre/+) mice were provided by Drs. Franco DeMayo and John Lydon [27]. B6.129-Cdh1tmKem2/J (i.e., Cdh1flox; Jax #005319) and B6.129S4-Ptentm1Hwu (i.e., Ptenflox; Jax #006440) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. The genotypes of mutant mice were determined by PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA. To assess the effects of loss of Cdh1 and/or Pten on neonatal uterine morphogenesis, female pups were necropsied on Postnatal Days 15 and 16 (n = 8–20). Two hours before euthanasia, pups received an i.p. injection of 100 mg/kg of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma) to assess cell proliferation. At collection, uterine tissues were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 8–12 h and embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemical and TUNEL Analysis

Immunolocalization of BrdU, KRT8, ACTA2, PECAM1, ESR1, PGR, CTNNB1, CLDN, and pAKT was performed in cross sections (5 μm) of paraffin-embedded uterine sections using specific antibodies and a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Antibodies used in these analyses were anti-BrdU (1:200 dilution; 11 170 376 001; Roche), anti-KRT8 (1:500 dilution; MMS-162P; Covance), anti-ACTA2 (1:500 dilution; ab5694; Abcam), PECAM1 (1:100 dilution; ms728S0; Thermo Fisher), anti-ESR1 (1:100 dilution; sc-542; SantaCruz), anti-PGR (1:200 dilution; RB-9017-P0; Thermo Fisher), anti-CTNNB1 (1:250 dilution; 610513; BD), anti-claudin (1:200 dilution; 51–9000; Invitrogen), and pAKT (1:200 dilution; 3787; Cell Signaling), and negative controls were performed in which the primary antibody was substituted with the same concentration of normal IgG (Sigma). Antigen retrieval using a boiling citrate buffer was performed as described previously [22]. The TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using the ApopTag Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore).

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival rates were determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and P values were determined by a log-rank test using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad). All experimental data were subjected to one-way ANOVA, and differences between individual means were tested by a Tukey multiple-range test using Prism 4.0. Tests of significance were performed using the appropriate error terms according to the expectation of the mean squares for error. P < 0.05 or less was considered significant. Data are presented as least-square means with SEM.

RESULTS

Impact of Conditional Ablation of Cdh1 and Pten in Neonatal Uterus

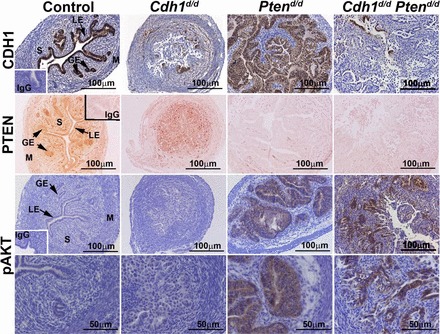

Cdh1- and Pten-null mice show early embryonic lethality [28–30]. In order to examine the role of CDH1 and/or PTEN in the uterus, conditional ablation of Cdh1 and/or Pten was conducted to circumvent the embryonic lethal phenotype. We utilized the PgrCre/+ mouse line in which Cre recombinase is under the control of the Pgr promoter [27]. PgrCre/+ mice were crossed with Cdh1f/f and/or Ptenf/f mice to provide a tissue-specific knockout of Cdh1 and/or Pten in Pgr-expressing cells (PgrCre/+ Cdh1f/f = Cdh1d/d, PgrCre/+ Ptenf/f = Ptend/d, and PgrCre/+ Cdh1f/f Ptenf/f = Cdh1d/d Ptend/d). Although Cre recombinase in PgrCre/+ mice is active in all cell types of uterus, ablation of both Cdh1 and Pten in the uterus only occurs in the epithelial cells, as endogenous CDH1 is expressed only in the uterine epithelium. It is to be noted that PGR is expressed in the oviduct, ovary, mammary gland, and pituitary. However, we did not see any abnormalities in other tissues in Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, or Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice at 2 wk of age (data not shown). To validate CDH1 and/or PTEN ablation, CDH1 and/or PTEN immunoreactivity was determined in the uterus (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed that CDH1 and/or PTEN proteins were ablated by Pgr-driven Cre activity. Further, ablation of Pten either alone or with Cdh1 resulted in increased activation of AKT (pAKT) as expected (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of conditional ablation of Cdh1 and Pten induced by PgrCre/+ mice in mouse uterus. Immunolocalization of CDH1, PTEN, and phospho-AKT (pAKT) in the uteri of control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice on Days 15 and 16 of age. GE, glandular epithelium; LE, luminal epithelium; M, myometrium; S, stroma.

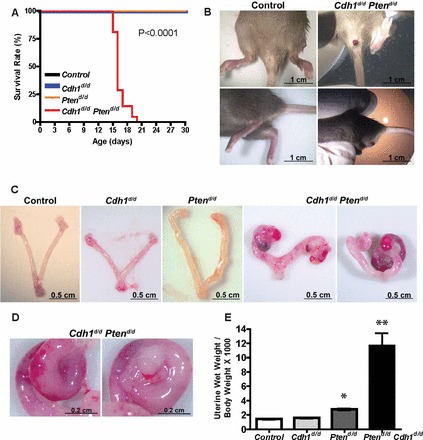

Ablation of Pten alone in the uterus was shown to affect viability of mice starting around 5 mo of age due to growing primary endometrial carcinomas ([5] and Hayashi, unpublished observation). Therefore, we first examined the lifespan of control (Pgr+/+ Cdh1f/f Ptenf/f), Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. The survival time of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice was significantly reduced compared to that of control, Cdh1d/d, and Ptend/d mice (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A). All Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice died between Days 15 and 19 of age. The average lifespan of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice was 16 days. To further investigate the impact of Cdh1 and Pten ablation in the uterus, control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice were euthanized at Days 15 and 16 of age. At euthanization, we observed excessive uterine bleeding (metrorrhagia) and abnormal swollen genital tracts in Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice (Fig. 2B). Excised uteri were weighed, and gross morphology was examined. Ptend/d mice showed longer and curved uterine horns, while Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice exhibited curly uterine horns with massive blood in the uterus (Fig. 2, C and D). Further, the uterine wet weight of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice was significantly increased compared to that of other genotypes of mice, including Ptend/d mice (Fig. 2E; P < 0.05; P < 0.001 vs. control). Cdh1d/d mice did not exhibit any changes in gross uterine morphology and uterine wet weight, as previously published [22].

FIG. 2.

Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice show aberrant uteri and reduced survival. A) Overall survival rate for control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice (n = 8–20) was performed by Kaplan-Meier analysis to assess whether ablation of Cdh1 and Pten is associated with short lifespan (P < 0.0001). All mice were monitored for any sign of sickness. We euthanized mice with any sign of sickness or discomfort, and the day of euthanasia was recorded. B) Overview of genital tract in control and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice before euthanasia. C) Gross morphology of control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice on Days 15 and 16 of age. D) High magnification of curly uterine horn in Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. E) The ratio of uterine wet weight to body weight in control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 versus control.

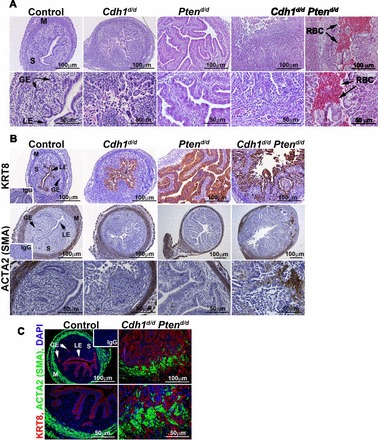

Histological analysis was conducted in the uteri from control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice (Fig. 3A). In agreement with our previous report [22], uteri of Cdh1d/d mice exhibited a disorganized cellular structure of epithelium and disrupted endometrial adenogenesis. Ptend/d mice exhibited complex hyperplastic epithelial development. The uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice resulted in extremely abnormal epithelial development with papillary differentiation, but lacked columnar atypical epithelia without complex hyperplasia or formed epithelial layers. To validate abnormal epithelial development, expression of an epithelial-specific marker, cytokeratin 8 (KRT8) [22], was assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3B). Staining with KRT8 confirmed that the epithelial cell population was located throughout the endometrium in Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. However, these epithelial cells histologically did not show a hyperplastic phenotype like those of the uteri of Ptend/d mice. In addition, they did not form normal uterine glands. Although Cdh1d/d mice showed disorganized epithelial cells, these cells were confined to the epithelial compartment and/or lumen. Thus, the ratio of epithelia/stroma in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice is higher than that of Cdh1d/d mice. When we performed immunohistochemical analysis of ACTA2 (smooth muscle alpha actin), which is an established marker of smooth muscle [22], the endometrium was surround by myometrial layers in the uteri of control, Cdh1d/d, and Ptend/d mice (Fig. 3B). However, Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice had an indistinguishable border between the endometrium and myometrium (Fig. 3B, high magnification). Costaining of KRT8 and ACTA2 in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice clearly exhibited that epithelial cells had invaded into the myometrium (Fig. 3C). While myometrial invasion is observed in the uteri of Ptend/d mice at 3 mo of age [5], ablation of Cdh1 and Pten exacerbated the invasion at a much earlier age (Postnatal Days 15 and 16). Further, invading epithelial cells in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice were widely disseminated in the myometrium, whereas Ptend/d mice developed glandular-like epithelia between the outer and inner myometrial layers [5]. These results indicate that ablation of Cdh1 and Pten accelerates abnormal epithelial development, cellular invasiveness, and dissemination.

FIG. 3.

Uterine histology from mice with ablation of Cdh1 and/or Pten. A) Uterine histology of control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice on Days 15 and 16 of age. Tissues were stained using hematoxylin and eosin. B) KRT8 (cytokeratin 8) and ACTA2 (smooth muscle alpha actin) were detected by immunohistochemistry. C) Costaining of KRT8 and ACTA2 in the uteri of control and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice was determined by immunofluorescence. GE, glandular epithelium; LE, luminal epithelium; M, myometrium; RBC, red blood cells; S, stroma.

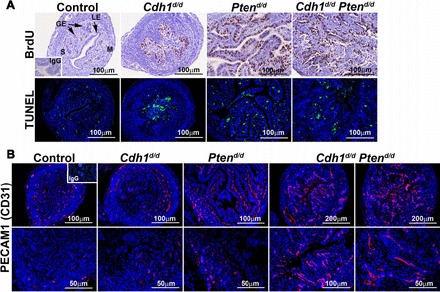

Ablation of Cdh1 and Pten Stimulates Angiogenesis

To determine whether increased uterine gross morphology and uterine wet weight in Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice resulted from alterations in cell proliferation and/or apoptosis, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of BrdU incorporation and TUNEL assays (Fig. 4A). The majority of the epithelial cells were BrdU positive in the uteri of Ptend/d and Cdh1d/d mice, confirming previous results [5, 22]. Cell proliferation was increased in the epithelia of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. However, we did not see differences in cell proliferation between Ptend/d and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. TUNEL analysis also revealed no obvious differences in apoptotic cell number in the uteri of Ptend/d and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. Next, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of PECAM1 (CD31), a marker of endothelial cells, to determine whether active angiogenesis occurred in the uteri (Fig. 4B). Although we observed positive PECAM1 in the uteri of all phenotypes as expected, the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice showed an abundant and more complex pattern of PECAM1 staining, revealing larger blood vessels, suggesting that angiogenesis is more active in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice than in those of other phenotypes.

FIG. 4.

The effect of Cdh1 and/or Pten ablation on proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. A) BrdU incorporation was detected by immunohistochemistry. Cellular apoptosis was determined by TUNEL analysis. B) Endothelial cell marker PECAM1 (CD31) was detected by immunofluorescence. GE, glandular epithelium; LE, luminal epithelium; M, myometrium; S, stroma.

Downregulation of Steroid Hormone Receptors and Adherens and Tight Junction Molecules by Ablation of Pten and Cdh1 in the Uterus

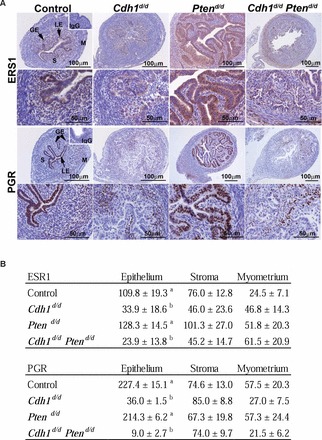

To determine whether abnormal epithelial development affects steroid hormone receptors, we examined the expression of ESR1 and PGR by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5A). Immunoreactivity of ESR1 and PGR was semiquantitatively scored by H-score analysis ([31]; Fig. 5B). ESR1 staining was detected in most of the uterine cell types in control mice, and its expression remained prominent in Ptend/d mice. Specifically, ESR1 was positive in the hyperplastic epithelial cells of Ptend/d mice. The expression of PGR was also detected in most of the uterine cell types of control mice. Specifically, PGR was abundant in the epithelial cells in control mice and remained positive in Ptend/d mice. However, ESR1 and PGR were significantly decreased in the epithelium of Cdh1d/d and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice (P < 0.01), but not in other cell types.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of steroid hormone receptors in the mouse uterus. A) Immunoreactive ESR1 and PGR were detected in the uteri of control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice on Days 15 and 16 of age. B) Semiquantitatively scored by H-score analysis. GE, glandular epithelium; LE, luminal epithelium; M, myometrium; S, stroma. a, b; P < 0.01.

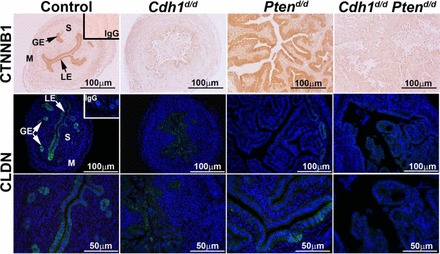

Since we have not seen the hyperplastic phenotype of epithelial cells in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice, cell-cell connection is expected to be affected by loss of Cdh1 in the uterus. Therefore, we examined the localization of an adherens junction molecule, CTNNB1 associated with CDH1 in the cytoplasm, and a tight junction molecule, CLDN (claudin) associated with the adherens junctions (Fig. 6). The critical intracellular mediator CTNNB1 was abundant in the epithelium of control and Ptend/d mice, but absent in Cdh1d/d and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. CLDN is an epithelial-specific molecule localized to the cell membrane. In control uteri, CLDN was clearly detected in the cell membrane of the epithelium. Cdh1d/d uteri did not show a cell membrane expression pattern of CLDN, but CLDN was still positive in several epithelial cells. Interestingly, CLDN was not observed in the hyperplastic epithelium in Ptend/d mice except in epithelial cells close to the myometrium. Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice lost CLDN expression in the uterus.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of adherens junction and tight junction molecules in the mouse uterus. Immunoreactive CTNNB1 and CLDN were detected in the uteri of control, Cdh1d/d, Ptend/d, and Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice on Days 15 and 16 of age. GE, glandular epithelium; LE, luminal epithelium; M, myometrium; S, stroma.

DISCUSSION

Loss of CDH1 function through genetic or epigenetic mechanisms has been implicated in the progression and metastasis of numerous malignancies [20, 32–42]. Negative or reduced expression of CDH1 is also associated with aggressive and invasive features of endometrial carcinomas [4, 13, 43, 44]. However, single-gene ablation of Cdh1 in the mouse uterus does not induce tumorigenesis [22], indicating that loss of Cdh1 alone does not contribute to tumor initiation and progression. In the present study, we report that loss of Pten, which is one of the most widely mutated genes in endometrial cancer, along with Cdh1 ablation induces severe uterine phenotypes. We observed that uterine deletion of both Pten and Cdh1 advances mortality. We also found that ablation of Pten and Cdh1 accelerates the features of neoplastic transformation in the uterus by inducing myometrial invasion, proliferation, massive angiogenesis, and loss of steroid hormone receptors. Thus, these findings suggest that loss of Cdh1 promotes aggressive endometrial cancer phenotypes when cells are initiated by ablation of Pten.

PTEN mutations are well documented in endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia [2–4, 45]. Loss of PTEN is likely an early event in endometrial tumorigenesis, as evidenced by its presence in precancerous lesions (simple to complex hyperplasia) [2, 3]. PTEN antagonizes the PI3K/AKT pathway by dephosphorylating PIP3, which is a second messenger that regulates the phosphorylation of AKT [8]. AKT regulates a variety of target molecules that control cell proliferation and survival. Thus, loss of PTEN results in the ability of cells to both proliferate and escape cellular senescence, and then induces hyperplastic epithelial proliferation [2]. On the other hand, most of the patients who are diagnosed with complex atypical hyperplasia and well-differentiated endometrioid carcinomas usually show high overall survival (85% at 5 yr after initial diagnosis) following simple hysterectomy and/or progestin therapy, because tumors usually stay within the uterus [2–4]. In fact, the mouse model with uterine-specific, single-gene ablation of Pten is characterized by complex atypical hyperplasia, focal carcinomas, and metaplasia, but does not induce metastatic diseases [5]. However, high-grade endometrioid carcinomas exhibit undifferentiated and invasive features with significant morbidity [2, 46]. The present study showed that ablation of Cdh1 disrupted epithelial cellular structure in the uterus, as CDH1 is one of the main mediators of cell-to-cell adhesion in epithelial cells. When both Pten and Cdh1 were ablated in the uterus, we saw the first signs of epithelial cell invasion into the myometrium, with active proliferation at an early age. Although loss of Cdh1 in the uterus also increased proliferation, we did not see any myometrial invasion in the uteri of Cdh1d/d mice. Negative and reduced expression of CDH1 has been reported to be associated with advanced stage and poor differentiation, as well as a feature of high-grade endometrioid carcinomas [13]. Thus, these results suggest that hyperplastic endometrial cells initiated by ablation of Pten give rise to undifferentiated and invasive phenotypes, similar to advanced-stage endometrial carcinomas, when CDH1 function is inactive.

Aberrant cellular invasiveness, typically accelerated by loss of CDH1, is a hallmark property of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is induced by several growth factors, such as TGFβ, HGF, IGF, and FGF, as well as MMPs [47]. Their receptor complexes contribute to loss of CDH1 function by inducing the expression of multiple known transcriptional repressors (SNAIL, SLUG, TWIST, and ZEB) of Cdh1. In our study, the expression of these transcriptional repressors was not altered compared to those of control tissues (data not shown), as any EMT-like character in our model stems from direct deletion of Cdh1 and not alteration of other signaling networks that operate upstream or in conjunction with CDH1 signaling. Our results showed that cellular invasiveness was observed in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice, but not Cdh1d/d mice. Thus, deletion of both Pten and Cdh1 in the uterus causes EMT-like phenotypes. Recent reports have indicated that EMT is a dynamic process controlled by signals that cells receive from their microenvironment, which consists of stromal cells, endothelial cells, carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and immune cells [47, 48]. CAFs are able to stimulate tumor angiogenesis by attracting endothelial precursor cells [47, 49]. Tumor-associated macrophages are also involved in angiogenesis [50]. In the present study, we observed complex angiogenesis in the uteri of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice. While endothelial cells were only detected in distinct stroma and myometrium of control, Cdh1d/d, or Ptend/d mice, massive endothelial cells were observed in the entire uterus of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice, indicating that blood vessels had migrated and invaded into endometrium and myometrium, a hallmark feature of the developing tumor microenvironment. In support of these results, extensive uterine bleeding was observed in the uteri of these mice. Thus, it is expected that ablation of Pten and Cdh1 induces an invasive character in the cells, and invasive tumor cells have EMT potential that further potentiates invasive or migratory ability leading to establishment of the tumor microenvironment. However, the precise mechanism remains to be directly investigated.

Expression of ESR1 and PGR in endometrial cancer usually signifies that the tumors are well differentiated [51]. Loss of PTEN is likely initiated in response to known hormonal risk factors. However, expression of these receptors declines in tumors that are poorly differentiated or of higher grade [51]. Although the reasons for decreasing expression of steroid hormone receptors are not well known, women with endometrial hyperplasia and/or well-differentiated endometrial adenocarcinomas have a good response to progestin therapy [52, 53]. Thus, clinical response, overall survival, and recurrence rates generally correlate to the expression of steroid hormone receptors. The present study showed that loss of Cdh1 in the uterus is associated with the reduced expression of steroid hormone receptors. Because inactivation of CDH1 is one of the key features of invasive and aggressive cancer, CDH1 may regulate expression of steroid hormone receptors in the uterus. Specifically, PGR and ESR1 were also decreased in epithelial cells by single ablation of Cdh1. Further, cell adhesion molecules, CTNNB1 and CLDN, were also suppressed. Thus, adhesive and well-differentiated epithelial cellular structures may be necessary for functional steroid hormone receptors in the uterus. Nevertheless, the results of reduced PGR and ESR1 caused by ablation of Cdh1 support the fact that high grades of endometrial cancer are unresponsive to progestin therapy. Therefore, these results suggest that ablation of Cdh1 followed by Pten deletion induces not only histological and morphological characteristics of high-grade endometrial cancer but functional and therapeutic features of this disease as well.

Collectively, the results of the present study indicate that combined loss of Cdh1 and Pten resulted in accelerated development of invasive neoplastic transformation, which shows strong resemblance to high-grade endometrial carcinomas. However, Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice die at Days 15–19 of age. The cause of early death in Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice is probably due to excess uterine bleeding caused by invasion of uterine blood vessels. While metrorrhagia with massive angiogenesis and myometrial invasion are known to be critical features of aggressive and high-grade endometrial carcinomas, we did not see any signs of metastasis in the peritoneum and other organs, as these mice had such a short lifespan. Because morphological and functional phenotypes of Cdh1d/d Ptend/d mice are unique and similar to high-grade endometrial carcinomas, it is necessary to further characterize invasive mechanisms relating to metastatic potential in these mice. Currently, we are characterizing invasive tumors caused by ablation of Pten and Cdh1 in a model that utilizes orthotopic implantation of transgenic uterine tissues into the uterus of wild-type syngeneic host mice to examine tumor dissemination and metastasis beyond the lifespan of the donor mice.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/NICHD HD0588222, ACS-IL 139038, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine EAM, and Southern Illinois University Carbondale SEED (to K.H.). This study was presented in part at the 45th annual meeting of the Society of the Study of Reproduction, August 12–15, 2012, State College, Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62: 10 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, Ellenson LH. Endometrial carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol 2007; 2: 57 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal N, Yendluri V, Wenham RM. The molecular biology of endometrial cancers and the implications for pathogenesis, classification, and targeted therapies. Cancer Control 2009; 16: 8 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarnthai N, Hall K, Yeh IT. Molecular profiling of endometrial malignancies. Obstet Gynecol Int 2010; 2010: 162363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T, Hirota Y, Tranguch S, Joshi AR, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Ellenson LH, Dey SK. Conditional loss of uterine Pten unfailingly and rapidly induces endometrial cancer in mice. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 5619 5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarzadeh S, Zong Y, Janzen DM, Goldstein AS, Cheng D, Kurita T, Schafenacker AM, Huang J, Witte ON. Cell-autonomous activation of the PI3-kinase pathway initiates endometrial cancer from adult uterine epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 17298 17303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, Xu PZ, Peng XD, Chen WS, Guzman G, Yang X, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Hay N. The deficiency of Akt1 is sufficient to suppress tumor development in Pten+/− mice. Genes Dev 2006; 20: 1569 1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell 2003; 4: 257 262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Hennessy BT, Li J, Yu S, Myers AP, Djordjevic B, Lu Y, Stemke-Hale K, Dyer MD, Zhang F, Ju Z, Cantley LC, et al. High frequency of PIK3R1 and PIK3R2 mutations in endometrial cancer elucidates a novel mechanism for regulation of PTEN protein stability. Cancer Discov 2011; 1: 170 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M. Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1995; 7: 619 627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleminckx K, Kemler R. Cadherins and tissue formation: integrating adhesion and signaling. Bioessays 1999; 21: 211 220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huszar M, Pfeifer M, Schirmer U, Kiefel H, Konecny GE, Ben-Arie A, Edler L, Munch M, Muller-Holzner E, Jerabek-Klestil S, Abdel-Azim S, Marth C, et al. Up-regulation of L1CAM is linked to loss of hormone receptors and E-cadherin in aggressive subtypes of endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol 2010; 220: 551 561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncuoglu M, Okyay E, Saatli B, Olgan S, Akin M, Saygili U. Tumor budding and E-Cadherin expression in endometrial carcinoma: are they prognostic factors in endometrial cancer? Gynecol Oncol 2012; 125: 208 213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R, Mitze M, Frixen UH, Birchmeier W. Differential loss of E-cadherin expression in infiltrating ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 1731 1742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZY, Zhan WH, Li JH, He YL, Wang JP, Lan P, Peng JS, Cai SR. Expression of E-cadherin in gastric carcinoma and its correlation with lymph node micrometastasis. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 3139 3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes RM, Veve R, Hirsch FR, Franklin WA. The E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion complex and lung cancer invasion, metastasis, and prognosis. Lung Cancer 2002; 36: 115 124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marzo AM, Knudsen B, Chan-Tack K, Epstein JI. E-cadherin expression as a marker of tumor aggressiveness in routinely processed radical prostatectomy specimens. Urology 1999; 53: 707 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llobet D, Pallares J, Yeramian A, Santacana M, Eritja N, Velasco A, Dolcet X, Matias-Guiu X. Molecular pathology of endometrial carcinoma: practical aspects from the diagnostic and therapeutic viewpoints. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62: 777 785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka H, Shiozaki H, Kobayashi K, Inoue M, Tahara H, Kobayashi T, Takatsuka Y, Matsuyoshi N, Hirano S, Takeichi M, Mori T. Expression of E-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in human breast cancer tissues and its relationship to metastasis. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 1696 1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl AK, Wilgenbus P, Dahl U, Semb H, Christofori G. A causal role for E-cadherin in the transition from adenoma to carcinoma. Nature 1998; 392: 190 193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M. Cadherins in cancer: implications for invasion and metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1993; 5: 806 811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SN, King ML, MacLean JA II, Mann JL, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Hayashi K. CDH1 is essential for endometrial differentiation, gland development, and adult function in the mouse uterus. Biol Reprod 2012; 86 (5): 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussadia O, Kutsch S, Hierholzer A, Delmas V, Kemler R. E-cadherin is a survival factor for the lactating mouse mammary gland. Mech Dev 2002; 115: 53 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen PW, Braumuller TM, van der Burg E, Hornsveld M, Mesman E, Wesseling J, Krimpenfort P, Jonkers J. Mammary-specific inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 impairs functional gland development and leads to pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinoma in mice. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4: 347 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen PW, Liu X, Saridin F, van der Gulden H, Zevenhoven J, Evers B, van Beijnum JR, Griffioen AW, Vink J, Krimpenfort P, Peterse JL, Cardiff RD, et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2006; 10: 437 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada S, Mimata A, Sekine M, Mogushi K, Akiyama Y, Fukamachi H, Jonkers J, Tanaka H, Eishi Y, Yuasa Y. Synergistic tumour suppressor activity of E-cadherin and p53 in a conditional mouse model for metastatic diffuse-type gastric cancer. Gut 2012; 61: 344 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, Li J, Li H, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 2005; 41: 58 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue L, Ohsugi M, Hirchenhain J, Kemler R. E-cadherin null mutant embryos fail to form a trophectoderm epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91: 8263 8267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethmacher D, Brinkmann V, Birchmeier C. A targeted mutation in the mouse E-cadherin gene results in defective preimplantation development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92: 855 859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Tsao MS, Macpherson D, Suzuki A, Chapman WB, Mak TW. High incidence of breast and endometrial neoplasia resembling human Cowden syndrome in pten+/− mice. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 3605 3611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi H, Suzuki T, Suzuki S, Moriya T, Kaneko C, Takizawa T, Sunamori M, Handa M, Kondo T, Sasano H. Sex steroid hormone receptors in human thymoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 2309 2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle E, Sancho E, Franci C, Dominguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, Garcia De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 84 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Becker KF, Hofler H, van Roy F. Mutations of the human E-cadherin (CDH1) gene. Hum Mutat 1998; 12: 226 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 76 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleton-Jansen AM, Moerland EW, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn NJ, Callen DF, Sutherland GR, Hansen B, Devilee P, Cornelisse CJ. At least two different regions are involved in allelic imbalance on chromosome arm 16q in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1994; 9: 101 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell 2001; 7: 1267 1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frixen UH, Behrens J, Sachs M, Eberle G, Voss B, Warda A, Lochner D, Birchmeier W. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol 1991; 113: 173 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Herman JG, Lapidus RG, Chopra H, Xu R, Jarrard DF, Isaacs WB, Pitha PM, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. E-cadherin expression is silenced by DNA hypermethylation in human breast and prostate carcinomas. Cancer Res 1995; 55: 5195 5199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Kanai Y, Oyama T, Yoshiura K, Shimoyama Y, Birchmeier W, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S. E-cadherin gene mutations in human gastric carcinoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91: 1858 1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savagner P, Yamada KM, Thiery JP. The zinc-finger protein slug causes desmosome dissociation, an initial and necessary step for growth factor-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol 1997; 137: 1403 1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleminckx K, Vakaet L Jr, Mareel M, Fiers W, van Roy F. Genetic manipulation of E-cadherin expression by epithelial tumor cells reveals an invasion suppressor role. Cell 1991; 66: 107 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell 2004; 117: 927 939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb K, Delatorre R, Pedemonte B, McLeod C, Anderson L, Chambers J. E-cadherin expression in endometrioid, papillary serous, and clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100: 1290 1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaco-Levy R, Sharabi S, Piura B, Sion-Vardy N. MMP-2, TIMP-1, E-cadherin, and beta-catenin expression in endometrial serous carcinoma compared with low-grade endometrial endometrioid carcinoma and proliferative endometrium. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008; 87: 868 874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell GL, Risinger JI, Gumbs C, Shaw H, Bentley RC, Barrett JC, Berchuck A, Futreal PA. Mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in endometrial hyperplasias. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 2500 2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg SG. Problems in the differential diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 309 327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature 2006; 441: 444 450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhou BP. Inflammation: a driving force speeds cancer metastasis. Cell Cycle 2009; 8: 3267 3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, Washington MK, Neilson EG, Moses HL. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science 2004; 303: 848 851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R. Sergi Sergi L, Politi LS, Sampaolesi M, Naldini L. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell 2005; 8: 211 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Progesterone action in endometrial cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and breast cancer. Endocr Rev 2013; 34: 130 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich CE, Young PC, Stehman FB, Sutton GP, Alford WM. Steroid receptors and clinical outcome in patients with adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 158: 796 807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Bodurka DC, Sun CC, Levenback C. Hormonal therapy for the management of grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma: a literature review. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 95: 133 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]