Abstract

Latinas are more likely to exhibit late stage breast cancers at the time of diagnosis and have lower survival rates compared to white women. A contributing factor may be that Latinas have lower rates of mammography screening. This study was guided by the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use to examine factors associated with mammography screening utilization among middle-aged Latinas. An academic–community health center partnership collected data from community-based sample of 208 Latinas 40 years and older in the San Diego County who completed measures assessing psychosocial factors, health care access, and recent mammography screening. Results showed that 84.6 % had ever had a mammogram and 76.2 % of women had received a mammogram in the past 2 years. Characteristics associated with mammography screening adherence included a lower acculturation (OR 3.663) a recent physician visit in the past year (OR 6.304), and a greater confidence in filling out medical forms (OR 1.743), adjusting for covariates. Results demonstrate that an annual physical examination was the strongest predictor of recent breast cancer screening. Findings suggest that in this community, improving access to care among English-speaking Latinas and addressing health literacy issues are essential for promoting breast cancer screening utilization.

Keywords: Community–academic partnership research, Health services utilization, Mammography screening, Latinas, Breast cancer

Background

Regular use of mammography is associated with a decreased risk of developing invasive breast cancer (BC) [1] and has been estimated to reduce mortality by about 25 % in women aged 40 years and over [2, 3]. Although Latinas are less likely to develop BC than white women, Latinas are more likely to exhibit late stage cancers at time of diagnosis and have lower survival rates compared to white women in California [4] and nationwide [5]. A contributing factor may be that Latinas have lower rates of mammography use [6, 7].

Theoretical Framework

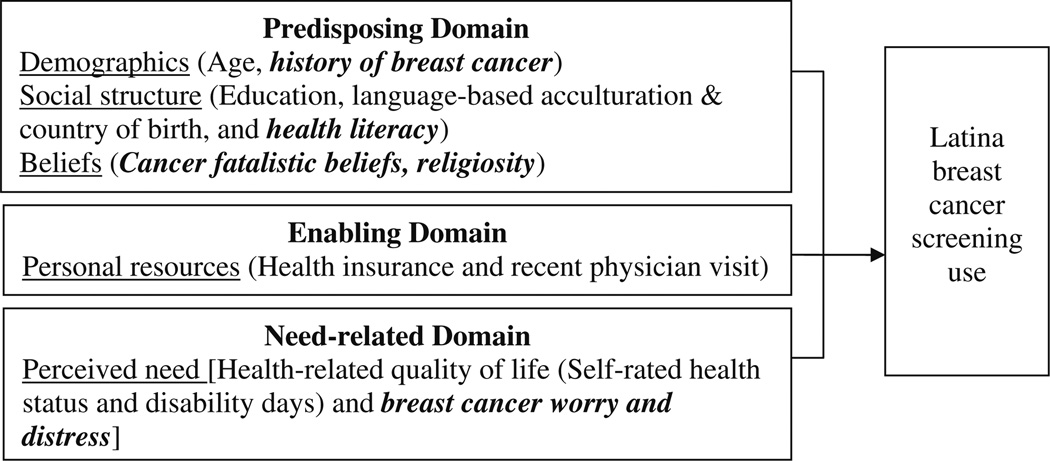

This study was guided by the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (BMHSU) to explain predictors of mammography use among Latinas. The BMHSU [8] was developed to explain why individuals use health care, and to define and measure equitable access to healthcare [9]. The BMHSU has been used as a framework to examine access and utilization of hospital, dental, and medical care among diverse adults [10–14], access to care and utilization barriers experienced by Latinos [15–18]. The BMHSU suggests that healthcare use is a function of an individual’s predisposition to use services, factors that enable use, and their need for care [9]. In the present study, relevant context-specific1 variables were added to the model because they were hypothesized to be relevant to Latinas, BC, or screening behavior [19]. Predisposing, enabling, and need domains are outlined below (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Behavioral model of health services utilization. Note. Traditional behavioral model of health services utilization domain variables are listed. Proposed contextual variables are bolded and italicized

Predisposing factors refer to characteristics that affect the likelihood of health care utilization and include: demographics, social structure, and health beliefs [13]. Age and personal/family history of cancer are two demographic variables targeted in this study. Older Latinas are more likely to use mammography than younger Latinas [17, 18]; however, some studies suggest that age is not significant after adjusting for other factors [20]. Latinas with a personal or family history of cancer show greater mammography use compared to those without history, which relates to an increased awareness and perceived risk of the disease [18, 21–24].

Social structure describes individual’s societal status [25] includes education, acculturation, and health literacy. Lower levels of education have been shown to impede BC screening among Latinas [18, 26–31]. The literature offers no consensus on the role of language-based acculturation and country of birth in predicting BC screening [17, 18, 32–38]. An innovative social structure variable not previously examined in studies using the BMHSU is health literacy (HL). Studies show that inadequate HL relates to a lack of knowledge about the importance of and reasons for preventive health services [39] and low HL relates to mammography underutilization in Latinas and misunderstandings of cancer risk [40].

Health beliefs include attitudes, values, and knowledge that people have about health and health services that may influence use [25]. Health belief variables, not included in the original BMHSU, include cancer fatalistic beliefs and religiosity. Fatalistic beliefs promote an external locus of control, which can deter mammography utilization [41–43]. Latinas can have fatalistic beliefs and misconceptions about cancer, such as divine predetermination as a cause [7, 44–47], which impede use of cancer screening exams [35, 44, 48–50]. Religiosity involves beliefs, behaviors, and personal devotion [51], and is a key facet of Latino culture that promotes health behaviors [52]. Some studies have shown that church attendance is related with a healthier dietary and physical activity [53] and BC screening among Latinas [35].

Enabling factors are defined as conditions that make accessing services possible [9]. The ability to secure health services is affected by personal resources, including health insurance and access to a regular health care source [25]. Studies show that having any health insurance [5, 17, 18, 20, 26, 28, 29, 31, 35, 36, 54, 55]; visiting a physician in the past year [6, 18] or having a usual source of care [5, 17, 38, 54, 56, 57] enables use of mammography among Latinas.

An individual must perceive a need for health care in order for health care utilization to occur [25]. Subjective need is typically measured by health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (i.e., self-rated health status, unhealthy days, and activity limitation) [58, 59]. A lower HRQOL is related to increased general health care utilization [58]. In addition, self-rated health status (a component of HRQOL) has been shown to be significantly related mammography in Latinas [17], but was not associated with breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening in another study [60]. Within the context of screening, subjective need can also be conceptualized as individuals’ perceptions of future illness risk or concerns about becoming ill. In this study, need was also assessed by BC worry, the emotional reaction to the threat of BC that consists of both cognitive and affective elements [61, 62]. Worrying can stem from a fear of developing cancer, and fear is a barrier to cancer screening in Latinas [63, 64]. No consensus exists on whether worry promotes or inhibits screening [62]. For example, moderate levels of worry actually improve mammography rates [23, 61, 65– 67] yet extremely high levels of worry and distress are barriers to mammography screening [61, 68].

The aim of this study was to determine what predisposing, enabling, and need factors were associated with breast cancer screening among Latinas 40 years and older residing in San Diego County. It was hypothesized that variables in the predisposing, enabling, and need domains of the BMHSU would predict recent mammography screening. It was also hypothesized that adding contextspecific variables, not included in the original BMHSU, would improve the prediction of mammography screening utilization.

Methods

Participants and Setting

This study focused on San Diego County, California’s most southern region located adjacent to Baja California Norte, Mexico. As part of a larger community health center–academic partnership study funded by the California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP) community research collaborative program, survey data were collected in 2007–2008 through University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board-approved methods. The CBCRP study aimed to recruit 500 English and Spanishspeaking Latinas to complete surveys frequently used in health and research settings for later use to help evaluate the effectiveness of a culturally-tailored BC clinical trials education program.

Participants were drawn from a community sample of 503 Latinas 21 years and older; women 40 years and older (n = 208) were included for analysis. Eligible women were consented and participated in face-to-face interviews at community-based sites, and were recruited by snowballing and word-of-mouth strategies with the intent of reach women in a culturally competent non-invasive manner [69]. Ten refused to participate, with lack of time being the most frequent reason for refusal. Consented participants received $20.00 for their time and English and Spanish interviews took 60–90 min to complete. Eligibility criteria were: being an adult woman, self-identifying as Hispanic American and preferring English or Spanish for reading and writing.

Ages ranged from 40 to 80 years (M = 50.98; SD = 8.1). Among these, 47.3 % had a high school education or greater, 67.6 % had health insurance, 76.3 % were Mexican-born, and 56.3 % chose Spanish to fill out surveys. Given that the sample was recruited through non-probabilistic sampling strategies, it was important to determine the extent to which the sample was representative. Sample demographic and behavioral data were compared to state and county data; and results showed that the sample was comparable to state and local data on key factors, (e.g. mammography and age), except for health status. The study sample was less likely to report “excellent” health, and more likely to report “good” health, than Latinas sampled throughout San Diego County (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of sample demographics with county and state data

| Variable | Response | Sample (Latinas, 40+) % (n) |

San Diego County (Latinas, 40+) % (n) |

California (Latinas, 40+) % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 40–49 years old | 49.5 (103) | 46.1 (56,000) | 44.7 (832,000) |

| 50+ years old | 50.5 (105) | 55.9 (65,000) | 55.3 (1,028,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (208) | 100.0 (121,000) | 100.0 (1,860,000) | |

| Educationa | Did not graduate high school | 52.7 (109) | 60.2 (61,000) | 54.1 (858,000) |

| High school or higher | 47.3 (98) | 39.8 (40,000) | 45.9 (729,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (207) | 100.0 (101,000)** | 100.0 (1,587,000) | |

| Has health insurancea | Yes | 67.6 (140) | 77.5 (93,000) | 79.1 (1,471,000) |

| Otherwise | 32.4 (67) | 22.5 (27,000) | 20.9 (389,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (207) | 100.0 (120,000)* | 100.0 (1,860,000)* | |

| Health insurance categoriesa | Private | 51.7 (104) | 52.4 (63,000) | 45.3 (842,000) |

| Public | 14.9 (30) | 25.1 (30,000) | 33.8 (629,000) | |

| None | 33.3 (67) | 22.5 (27,000) | 20.9 (389,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (201) | 100.0 (120,000)* | 100.0 (1,860,000)* | |

| Country of birtha | Mexico | 76.3 (151) | 62.5 (70,000) | 53.8 (836,000) |

| United States | 23.7 (47) | 37.5 (42,000) | 45.9 (714,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (198) | 100.0 (112,000)* | 100.0 (1,555,000)* | |

| Ever had a mammograma | Yes | 84.6 (176) | 85.7 (104,000) | 88.0 (1,637,000) |

| No | 15.4 (32) | 14.3 (17,000) | 12.0 (224,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (208) | 100.0 (121,000) | 100.0 (1,861,000) | |

| Mammogram within the past | Yes | 76.2 (154) | n/a | 76.4 (274) |

| 2 years (40+)b | No | 23.8 (48) | 23.6 (89) | |

| Total | 100.0 (202) | 100.0 (363) | ||

| Mammogram within the past | Yes | 81.2 (82) | n/a | 84.8 (168) |

| 2 years (50+)b | No | 18.8 (19) | 15.2 (35) | |

| Total | 100.0 (101) | 100.0 (203) | ||

| Health statusa | Excellent | 8.3 (17) | 16.8 (20,000) | 10.2 (190,000) |

| Very Good | 19.0 (39) | 17.7 (21,000) | 20.0 (372,000) | |

| Good | 37.1 (76) | 27.4 (33,000) | 30.7 (571,000) | |

| Fair | 29.8 (61) | 32.3 (39,000) | 31.0 (576,000) | |

| Poor | 5.9 (12) | 5.8 (7,000) | 8.1 (151,000) | |

| Total | 100.0 (205) | 100.0 (120,000)* | 100.0 (1,860,000) |

Chi square analyses were run using an online Chi square calculator: http://home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/Business-stat/otherapplets/Catego.htm

Source: 2007 California Health Interview Survey (http://www.chis.ucla.edu/; San Diego County, California sample only includes Latinas 40 years and older

Source: 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey Data (http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSS/); California sample only includes Latinas 40 years and older

Difference from sample data were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01)

Difference from sample data were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05)

Measures

Mammography Screening

Recent mammography screening was assessed by an item derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire (BRFSS) [70]. A dichotomous variable was created to compare those compliant with federal screening guidelines [71] in place at the time of this study [i.e., recent mammogram in past 2 years to non-compliant (never screened or recent mammogram >2 years ago)]. Women were considered adherent if they had received at least one mammogram within the last 2 years.

Predisposing Domain Measures

Age was assessed by date of birth; a linear age variable and age categories (40–49 and 50 years and older) were created. Education was split into categories (<high school and ≥high school) [70]. Country of birth categories (i.e., United States and Mexico) were created. Language-based acculturation was assessed by the Brief Acculturation Measure for Hispanics (BASH), a four-item scale assessing language use and preference [72]. The four-item BASH had an alpha of 0.97 for the total sample (English α = 0.95, Spanish α = 0.85; lower alphas reflect the more limited variance in the language subgroups’ BASH scores). A mean score was created (ranging from one to five) with higher scores indicating greater acculturation. History of Breast Cancer (BC) was assessed by two items modified from the BRFSS [70] and a dichotomous variable was created (personal or family history of BC vs. otherwise). Health literacy (HL) was assessed by confidence in filling out medical forms and frequency of assistance needed in reading hospital materials [73]. The two items were significantly correlated in the total sample (r = 0.24) and in English (r = 0.35) (p ≤ 0.01); but not correlated in Spanish, thus the HL items were kept separate for analysis. Both items ranged from one to five; higher scores indicated higher HL. Religiosity was assessed by the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL), a five-item scale assessing organizational (religious services attendance), non-organizational, (private activities) and intrinsic religiousness (integration of religiosity into one’s life) [51]. Intrinsic religiosity was created by taking the mean of three of the items; this three-item scale had an alpha of 0.75 (English α = 0.80, Spanish α = 0.74), with responses ranging from one to five. Responses to organizational and non-organizational individual items range from 1 to 6. Higher scores reflected greater intrinsic, organizational, and non-organizational religiosity. Cancer fatalism was measured by the 15-item Powe Fatalism Inventory (PFI) [74, 75] and the Spanish PFI (SPFI) [76]. A modified version of the PFI was used and consisted of the following subscales: inevitability of death (items 11, 12, and 15), predetermination (items 1, 4, 5 and 9), and fear (items 8 and 10). Mean scores were created and range from 0 to 1, higher scores indicated more cancer fatalistic beliefs. Inevitability of death sub-scale had an alpha of 0.78 (SPFI α = 0.82, PFI α = 0.74), predetermination sub-scale had an alpha of 0.72 (SPFI α = 0.69, PFI α = 0.76), and the fear items were significantly correlated (r = 0.32; SPFI r = 0.34, PFI r = 0.32) (p ≤ 0.01).

Enabling Domain Measures

Health insurance and recent physician visit were derived from the BRFSS [70]. Health insurance was assessed by type of coverage. A dichotomous variable was created to compare insurance to none; two dummy variables were created to compare private (HMO, PPO, military), public (Medicaid and Medicare), and no insurance groups. Recent physician visit assessed time since last doctor visit for a routine checkup; a binary variable was created (visit in the past year vs. otherwise).

Need-Related Domain Measures

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was measured by the CDC HRQOL-4 [70], assessing: self-rated health, number of recent days with physical/mental health was impaired, and number of days of activity limitation due to poor physical/mental health [59]. The CDC HRQOL-4 has demonstrated reliability and validity for population use [77]. Self-rated health status ranges from one to give. The variable for unhealthy days was created by combining responses to recent impaired physical health and impaired mental health, with a logical maximum of 30 days. Activity limitation ranges from 0 to 30 and is the number of days of activity limitation due to unhealthy days. Higher scores indicated poorer health status, more unhealthy days, and more limitation days due to unhealthy days. The Cancer Worry Scale (CWS) was used to assess cognitive elements of recent worry and distress about developing BC [61, 78]. A BC worry three-item scale was created by averaging the first three items (ranged from one to three) and higher scores reflect more recent worry; this scale had an alpha of 0.86 (English α = 0.86, Spanish α = 0.87). The BC distress item ranged from one to three; higher scores reflected more recent distress about developing BC.

Statistical Analyses

Means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis were examined to ensure that variables were normally distributed. The HRQOL variable ‘activity limitation’ that was not normally distributed was transformed [79]. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to determine how the BMSHU variables loaded on an unspecified number of factors [80, 81]. Principal components extraction with orthogonal varimax rotation yielded a three factor solution, explaining 64.5 % of the variance. Using 0.4 as a cut-off criterion for factor loading (e.g., [82]), language-based acculturation, country of birth, and education loaded highly on factor 1 (predisposing); health status, unhealthy days, and activity limitation loaded highly on factor 2 (need); and health insurance, recent physician’s visit, and age loaded highly on factor 3 (enabling). Although age has been previously conceived of as part of the predisposing domain, age loaded on the enabling factor in the EFA. Age facilitates or enables use of screening because mammography screening is an age-dependent preventive service [71]. In addition, an increased age is a risk factor for developing breast cancer [1]. Older women are enabled to have a greater frequency of screening than younger women. Thus, a modified BMHSU—where age is treated as an indicator of the enabling domain rather than the predisposing domain—was more appropriate in these analyses. Subsequent logistic regression analyses were conducted with age as an enabling, rather than a predisposing variable. Based on prior studies using the BMHSU, [11, 12, 17, 18], this study used logistic regression models to test the direct effects of the three BMHSU domains [i.e., predisposing (Model 1), enabling (Model 2), and need (Model 3)] on recent mammography screening [83]. A hierarchical logistic regression analysis [83–86] was performed to determine the incremental prediction of adding variables not included in the original BMHSU [8, 25]. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.0.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Those who reported a mammogram in the last 2 years were significantly older (M = 52.0 years) than those who did not (M = 47.9 years) (p ≤ 0.05). Latinas who had a mammogram in the 2 years had a lower level of recent distress about developing breast cancer (M = 1.50, SD = 0.62) when compared to those who had a mammogram more than 2 years ago (M = 1.85, SD = 0.93) (p ≤ 0.05). Latinas who reported having a mammogram in the past 2 years (M = 4.03, SD = 1.00) had a greater confidence in filling out medical forms compared to those who reported having a mammogram more than 2 years ago (M = 3.63, SD = 1.16) (p ≤ 0.05). Latinas with any insurance were significantly more likely to have received a mammogram in the last 2 years (83.8 %), compared to Latinas without insurance (60.0 %) (p ≤ 0.05). Latinas that had visited a physician in the past year for a routine physical exam were significantly more likely to have received a mammogram in the last 2 years (85.8 %) compared to Latinas who had not visited a physician in the last year (56.7 %) (p ≤ 0.05). Screening did not differ by education, language-based acculturation, country of birth, health status, recent unhealthy days, or recent physical activity limitation, level of assistance needed in reading hospital materials, BC worry, a history of BC, level of cancer fatalistic beliefs, or degree of religiosity (Table 2).

Bivariate relationships with mammography screening use

| Behavioral model variables Chi square analyses |

Mammography (<2 years) % (n) |

Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Predisposing | |||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 71.7 (76) | 28.3 (30) | χ2(1, 201) = 2.412 |

| High school or greater | 81.1 (77) | 18.9 (18) | (p = 0.120) |

| Country of birth | |||

| United States | 74.5 (35) | 25.5 (12) | χ2(1, 193) = 0.047 |

| Mexico | 76.0 (111) | 24.0 (35) | (p = 0.828) |

| Enabling | |||

| Age | |||

| 40–49 years | 71.3 (72) | 28.7 (29) | χ2(1, 202) = 2.733 |

| 50+ | 81.2 (82) | 18.8 (19) | (p = 0.098)^ |

| Physician visit <1 year | |||

| Yes | 85.8 (115) | 14.2 (19) | χ2(1, 201) = 20.814 |

| No | 56.7 (38) | 43.3 (29) | (p = 0.000)* |

| Health insurance | |||

| Yes | 83.8 (114) | 16.2 (22) | χ2(1, 201) = 13.732 |

| No | 60.0 (39) | 40.0 (26) | (p = 0.000)* |

| Health insurance groups | |||

| Private | 84.0 (84) | 16.0 (16) | χ2(2, 195) = 13.476 |

| Public | 83.3 (25) | 16.7 (5) | (p = 0.001)* |

| None | 60.0 (39) | 40.0 (26) | |

| Behavioral model variables Mean comparisons |

Mammography (<2 years) M (SD) |

Sig. | |

| Yes | No | ||

| Predisposing | |||

| Language-based acculturationa | 2.35 (1.34) | 2.43 (1.49) | t = −0.102 |

| (n = 151) | (n = 44) | (df = 193, p = 0.919) | |

| Age (years) | 51.99 (9.25) | 47.86 (6.96) | t = 2.846 |

| (n = 154) | (n = 48) | (df = 200, p = 0.005)* | |

| Need | |||

| Health statusb | 2.99 (1.04) | 3.30 (0.97) | t = −1.823 |

| (n = 152) | (n = 47) | (df = 197, p = 0.070)^ | |

| Unhealthy daysb | 8.99 (10.66) | 12.32 (12.11) | t = −1.805 |

| (n = 148) | (n = 47) | (df = 193, p = 0.073)^ | |

| Activity limitationb | 5.55 (9.43) | 5.29 (9.13) | t = 0.143 |

| (n = 108) | (n = 35) | (df = 141, p = 0.806) | |

| Activity limitation transformedbc | 1.14 (0.20) | 1.13 (0.20) | t = 0.109 |

| (n = 108) | (n = 35) | (df = 141, p = 0.914) | |

| Contextual variables Chi square analyses |

Mammography (<2 years) % (n) |

Sig. | |

| Yes | No | ||

| History of breast cancer | |||

| Yes | 79.3 (46) | 20.7 (12) | χ2(1, 202) = 0.424 (p = 0.515) |

| No | 75.0 (108) | 25.0 (36) | |

| Contextual variables Mean comparisons | Mammography (<2 years) M (SD) |

Sig. | |

| Yes | No | ||

| Cancer fatalistic beliefs: predeterminationd | 0.46 (0.37) | 0.44 (0.34) | t = 0.330 |

| (n = 146) | (n = 46) | (df = 190, p = 0.742) | |

| Cancer fatalistic beliefs: inevitability of deathd | 0.17 (0.31) | 0.13 (0.28) | t = 0.777 (df = 196, p = 0.438) |

| (n = 150) | (n = 48) | ||

| Cancer fatalistic beliefs: feard | 0.65 (0.39) | 0.67 (0.40) | t = −0.289 |

| (n = 152) | (n = 48) | (df = 198, p = 0.773) | |

| Intrinsic religiosityd | 4.45 (0.80) | 4.40 (0.81) | t = 0.411 |

| (n = 151) | (n = 47) | (df = 196, p = 0.681) | |

| Organizational religiositye | 3.26 (1.21) | 3.11 (1.43) | t = 0.649 |

| (n = 145) | (n = 44) | (df = 187, p = 0.517) | |

| Non-organizational religiosityf | 3.08 (1.37) | 3.22 (1.44) | t = −0.513 |

| (n = 121) | (n = 37) | (df = 156, p = 0.609) | |

| Health literacy: confidence in filling out medical formsg | 4.03 (1.00) | 3.63 (1.16) | t = 2.360 |

| (n = 154) | (n = 48) | (df = 200, p = 0.019)** | |

| Health literacy: assistance needed in reading hospital materialsg | 3.75 (1.32) | 3.70 (1.52) | t = 0.224 |

| (n = 154) | (n = 47) | (df = 199, p = 0.823) | |

| Breast cancer worryh | 1.68 (0.66) | 1.64 (0.71) | t = 0.407 |

| (n = 152) | (n = 47) | (df = 197, p = 0.684) | |

| Breast cancer distressh | 1.50 (0.62) | 1.85 (0.93) | t = −2.961 |

| (n = 153) | (n = 47) | (df = 198, p = 0.003)* | |

Chi square tests and independent samples t tests (equal variances assumed) were used to compare variables across mammography adherence groups. Incomplete data are due to participant non-response

Approaching significance at the 0.05 level (0.05 [ p \ 0.10)

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤ 0.05

Possible range 1–5; higher scores denote higher acculturation to English language

Health status ranges from 1 to 5; unhealthy days and activity limitation range from 0 to 30; higher scores denote worse health status

Activity limitation transformed

Range from 0 to 1; higher scores denote higher levels of fatalistic beliefs

Ranges from 1 to 5; higher scores denote greater religiosity

Ranges from 1 to 6; higher scores denote greater religiosity

Ranges from 1 to 5, higher scores denote more confidence in filling out forms and less assistance needed

Range from 1 to 4; higher scores denote higher levels of worry and distress

Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Screening

Results from the three regression models assessing the predictability of each BMHSU domain showed that enabling and predisposing domains significantly predicted the likelihood of having a recent mammogram; the need domain was not associated with screening. Next, the three domains were entered simultaneously to test whether the BMHSU, as traditionally conceptualized, predicted recent BC screening utilization (Model 4). The model Chi square for Model 4 was significant (p ≤ 0.05) and explained a significant proportion of variance in BC screening (Menard [86]). In adjusted analyses, having a high school degree (OR 4.634), a lower language-based acculturation (OR 0.329), a greater age (OR 1.067), and a physician visit in the past year (OR 4.413) significantly predicted recent BC screening (p ≤ 0.05); all other variables were not significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Four logistic regression models of recent mammography screening

| Recent mammography (<2 years)a,c |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p value | |

| Model 1: predisposing domain | |||

| Education | |||

| <High schoolb | 1.000 | ||

| ≥High school | 2.999 | (1.154, 7.793) | 0.024** |

| Language-based acculturation | 0.641 | (0.414, 0.995) | 0.047** |

| Country of Birth | |||

| Mexicob | 1.000 | ||

| US | 2.042 | (0.590, 7.060) | 0.259 |

| Model 2: enabling domain | |||

| Age | 1.062 | (1.006, 1.120) | 0.029** |

| Health insurance | |||

| Noneb | 1.000 | ||

| Public | 1.746 | (0.538, 5.667) | 0.354 |

| Private | 2.391 | (1.093, 5.228) | 0.029** |

| Physician visit <1 year | |||

| Nob | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 3.336 | (1.603, 6.944) | 0.001* |

| Model 3: need domain | |||

| Health status | 0.877 | (0.580, 1.325) | 0.534 |

| Unhealthy days | 0.962 | (0.922, 1.004) | 0.078^ |

| Activity limitationd | 4.932 | (0.411, 59.214) | 0.208 |

| Model 4: Full BMHSU | |||

| Education | |||

| Less than high schoolb | 1.000 | ||

| High school or greater | 4.634 | (1.020, 21.062) | 0.047** |

| Language-based acculturation | 0.329 | (0.156, 0.693) | 0.003* |

| Country of birth | |||

| Mexicob | 1.000 | ||

| US | 4.945 | (0.708, 34.515) | 0.107 |

| Age | 1.067 | (1.010, 1.126) | 0.021** |

| Health insurance | |||

| Noneb | 1.000 | ||

| Public | 3.081 | (0.545, 17.420) | 0.203 |

| Private | 2.964 | (0.664, 13.236) | 0.155 |

| Physician visit <1 year | |||

| Nob | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 4.413 | (1.610, 12.094) | 0.004* |

| Health status | 0.885 | (0.484, 1.619) | 0.692 |

| Unhealthy days | 0.982 | (0.927, 1.040) | 0.540 |

| Activity limitationd | 1.069 | (0.046, 24.918) | 0.967 |

CI = confidence interval;

Approaching significance at the 0.05 level (0.05>p< 0.10);

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.05

Model 1: an = 185; b reference category, c model Chi square: 6.467 (df = 3, p = 0.091); GOF χ2 = 2.317, (df = 6, p = 0.888)

Model 2: an = 195; b reference category; c model Chi square: 29.355 (df = 4, p = 0.000); GOF χ2 = 4.568, (df = 8, p = 0.803)

Model 3: an = 141; c model Chi square: 3.819 (df = 3, p = 0.282); GOF χ2 = 4.155, (df = 8, p = 0.843); d activity limitation is transformed

Model 4: an = 124; b reference category; c model Chi square: 31.373 (df = 10, p = 0.001); GOF χ2 = 5.304, (df = 8, p = 0.725); d activity limitation is transformed

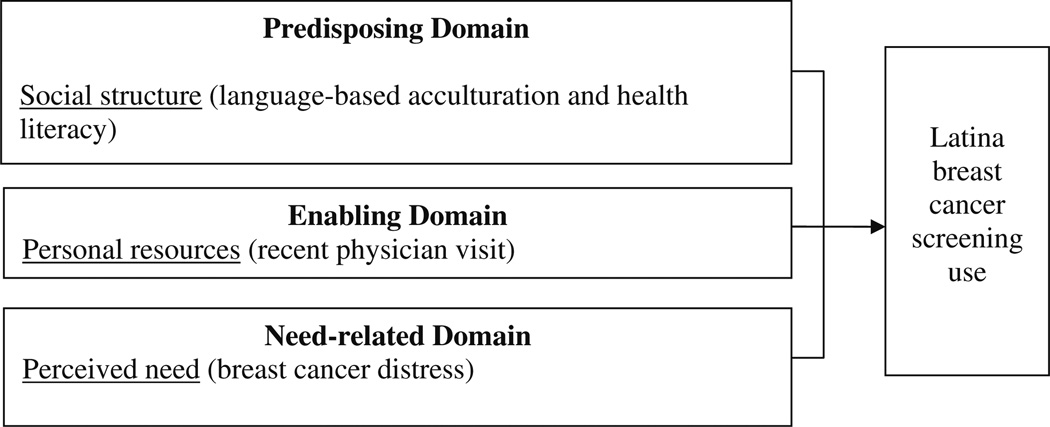

A hierarchical regression analysis was performed to determine the incremental prediction of the two contextual variables significant in bivariate analyses: step 1 including BMHSU variables (i.e., Model 5) and step 2 included confidence in filling out medical forms and breast cancer distress (e.g., Model 6). Model 6, including contained BMHSU variables plus the two context-specific variables, was a good fit to the data, and the two contextual variables significantly added to Model 5 (p ≤ 0.05), Thus, characteristics associated with BC screening adherence included a lower language-based acculturation (OR 3.663) a recent physician visit in the past year (OR 6.304), and a greater confidence in filling out medical forms (OR 1.743). Being US born (as compared to Mexican-born) (OR 6.210) was marginally insignificant (p < 0.10). Model 6 constitutes the final modified BMHSU (Table 4; Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Model comparisons: full BMHSU model (Model 5) and the modified BMSHU (Model 6)

| Factors | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography (<2 years)a |

Mammography (<2 years)a |

|||||

| OR | 95 % CI | p value | OR | 95 % CI | p value | |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high schoolb | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| High school or greater | 4.631 | (1.021, 21.002) | 0.047** | 3.075 | (0.624, 15.139) | 0.167 |

| Language-based Acc. | .330 | (0.157, 0.695) | 0.004** | 0.273 | (0.123, 0.605) | 0.001* |

| Country of Birth | ||||||

| Mexicob | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| US | 4.917 | (0.706, 34.246) | 0.108 | 6.210 | (0.777, 49.645) | 0.085^ |

| Age | 1.037 | (0.969, 1.109) | 0.298 | 1.044 | (0.970, 1.125) | 0.250 |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Noneb | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Public | 3.026 | (0.535, 17.123) | 0.211 | 2.804 | (0.451, 17.422) | 0.269 |

| Private | 2.959 | (0.664, 13.190) | 0.155 | 3.020 | (0.611, 14.940) | 0.175 |

| Physician visit <1 year | ||||||

| Nob | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 4.400 | (1.607, 12.050) | 0.004* | 6.304 | (2.074, 19.159) | 0.001* |

| Health status | 0.886 | (0.485, 1.619) | 0.694 | 0.991 | (0.512, 1.918) | 0.979 |

| Unhealthy days | 0.983 | (0.927, 1.041) | 0.552 | 0.994 | (0.934, 1.058) | 0.849 |

| Activity limitationc | 1.037 | (0.044, 24.373) | 0.982 | 1.812 | (0.061, 53.930) | 0.731 |

| Breast cancer distress | – | – | – | 0.540 | (0.263, 1.108) | 0.093^ |

| Confidence in filling out medical forms | – | – | – | 1.743 | (1.033, 2.940) | 0.037** |

| −2 log likelihood | 105.774d | 97.945e | ||||

Approaching significance at the 0.05 level (0.05 > p< 0.10);

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.05

n = 123

Reference category

Activity limitation is transformed

Model 5 Chi square: 30.888 (df = 10, p = 0.001); GOF χ2 = 5.226, (df = 8, p = 0.733)

Model 6 Chi square: 7.829 (df = 2, p = 0.020); GOF χ2= 13.558, (df = 8, p = 0.094). Model 6 was a better fit. A likelihood ratio χ2 test indicated that the two context-specific variables significantly added to the Model 5 [ > critical value , p≤ 0.05]

Fig. 2.

Modified behavioral model of health service utilization

Discussion

Use of health services can be conceptualized as discretionary or non-discretionary behavior [8, 9, 25]. The placement of and specified relationships between the predisposing, enabling, and need factors in the BMHSU varies depending on the character of the utilization variable under investigation [25]. Results from the current study imply that enabling and certain predisposing variables (i.e., language-based acculturation) contribute significantly to the prediction of BC screening utilization. These results support the original assumptions of the BMHSU, suggesting that for the discretionary use of health care—such as BC screening—the more likely utilization will be based on predisposing and enabling factors rather than need [8, 9, 25]. Since some research suggests that enabling factors, such as health insurance and a usual source of care matter more for BC screening than predisposing factors such as acculturation [5], studies are needed to explore these relationships further. Studies are also needed to determine the extent to which predisposing and need-related domains matter in the face of enabling domains for other disease contexts, types of health care use, and ethnic populations.

The modified BMHSU provided a reasonable framework for predicting the likelihood of BC screening among this sample of Latinas 40 years and older (Table 4; Fig. 2). Findings from the logistic regression analysis of the modified BMHSU showed that a lower language-based acculturation, a physician visit in the past year, and a greater confidence in filling out medical forms were important facilitators of BC screening use (Table 4). Some of these findings support prior research showing that a higher health literacy [87], visiting a physician in the past year [6, 18], and a higher age [17] promote BC screening among Latinas. Results from this study contrast the literature that deems a lack of health insurance [26, 36, 88] and being unacculturated [18, 34] as important barriers to mammography screening use among Latinas. Of note, breast cancer screening tests in San Diego are covered for the uninsured by California’s breast and cervical cancer early detection program “Every Woman Counts” [88]. This leads one to question the unique characteristics of the California–Mexico border context that enabled predominately Spanish-speaking Latinas in this study to obtain mammography screening, irrespective of their education level and country of birth. Results from this study confirm this lack of clarity in the relationship between breast cancer screening, access to care and acculturation.

Study Limitations

Secondary data were derived from a cross-sectional selfreport survey, which limited the ability to develop causal inferences about the relationships among variables examined. Due to the large, but single geographic focus, generalizations from these findings should be made with caution. Despite these limitations, results from this study have the potential to lend insight to future research, community-based health promotion, and primary care practice in relation to increasing mammography adherence among Latinas in the border region of Southern California.

Conclusions

Regular breast cancer screening increases early stage cancer detection and reduces the morbidity of late-stage diagnoses [89]. Andersen’s BMHSU [9] provided a reasonable framework for explaining mammography usage in this sample of Latinas 40 years and older. Future studies are needed to empirically test the BMSHU to determine how dependable it is across disease contexts, health care utilization types, and ethnic populations [90].

Results imply that interventions could focus on promoting mammography referrals by primary care health care providers [91, 92]. Since no other factor was more predictive of adherence to BC screening guidelines, the encouragement to have an annual physical examination appears to be the most important health promotion message to convey. Future research should explore the role that culturally competent primary care providers, as trusted sources of health information, play in motivating Latinas to obtain preventive health care services [93]. Research is also needed to explore the application of the Foot-in-the-Door method [94, 95], by which access to the health care system through non-invasive means leads to an increased receptivity to recommendations for more invasive procedures, such as mammography.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a California Breast Cancer Research Program/Community Research Collaborative Pilot Award to Sadler and Riley.

Footnotes

Context-specific variables are specifically related to the population, the disease, or the utilization behavior under investigation.

Contributor Information

Sheila F. Castañeda, Email: scastaneda@mail.sdsu.edu, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court, Suite 110, San Diego, CA 92123, USA.

Vanessa L. Malcarne, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, San Diego, CA, USA

Pennie G. Foster-Fishman, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

William S. Davidson, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Manpreet K. Mumman, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court, Suite 110, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

Natasha Riley, Vista Community Clinic, Vista, CA, USA.

Georgia R. Sadler, Moores UCSD Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Prevention (PDQ®) 2007 (cited 2012 December 7). http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/breast/Patient/

- 2.Elmore JG, et al. Screening for breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1245–1256. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells KJ, Roetzheim RG. Health disparities in receipt of screening mammography in Latinas: a critical review of recent literature. Cancer Control. 2007;14(4):369–379. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.California Cancer Registry. Public use data set: California cancer incidence and mortality rates plus interactive maps. 2008 (cited 2008 August 1). http://www.ccrcal.org/dataquery.html.

- 5.Zambrana RE, et al. Use of cancer screening practices by Hispanic women: analyses by subgroup. Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):466–477. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frazier EL, Jiles RB, Mayberry R. Use of screening mammography and clinical breast examinations among black, Hispanic, and white women. Prev Med. 1996;25(2):118–125. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbell FA, et al. Differing beliefs about breast cancer among Latinas and Anglo women. West J Med. 1996;164(5):405–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen RM. A behavioral model of families’ use of health services, Research Series No. 25. University of Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies; 1968. (cited 2012 August 1). http://www.chas.uchicago.edu/documents/Publications/RS/RS25.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen R, et al. Access of vulnerable groups to antiretroviral therapy among persons in care for HIV disease in the United States. HCSUS Consortium. HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(2):389–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller DC, et al. Racial disparities in access to care for men in a public assistance program for prostate cancer. J Community Health. 2008;33(5):318–335. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9105-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein JA, Andersen R, Gelberg L. Applying the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson KA, Andersen R, Gelberg L. Patient satisfaction for homeless women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12(7):675–686. doi: 10.1089/154099903322404320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen RM, Giachello AL, Aday LA. Access of Hispanics to health care and cuts in services: a state-of-the-art overview. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(3):238–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrada AL, Trevino FM, Ray LA. Health care utilization barriers among Mexican Americans: evidence from HHANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(Suppl):27–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez LE, Morales A. Language and use of cancer screening services among border and non-border Hispanic Texas women. Ethn Health. 2007;12(3):245–263. doi: 10.1080/13557850701235150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorin SS, Heck JE. Cancer screening among Latino subgroups in the United States. Prev Med. 2005;40(5):515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasick RJ, Burke NJ. A critical review of theory in breast cancer screening promotion across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:351–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.143420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Gammon MD. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas and non-Latina whites. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1393–1398. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aparicio-Ting F, Ramirez AG. Breast and cervical cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening practices of Hispanic women diagnosed with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2003;18(4):230–236. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1804_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen M. Breast cancer early detection, health beliefs, and cancer worries in randomly selected women with and without a family history of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(10):873–883. doi: 10.1002/pon.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCaul KD, et al. What is the relationship between breast cancer risk and mammography screening? A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 1996;15(6):423–429. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCaul KD, Tulloch HE. Cancer screening decisions. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25:52–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrasquillo O, Pati S. The role of health insurance on Pap smear and mammography utilization by immigrants living in the United States. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox P, et al. Patient and clinical site factors associated with rescreening behavior among older multiethnic, low-income women. Gerontologist. 2004;44(1):76–84. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones AR, Caplan LS, Davis MK. Racial/ethnic differences in the self-reported use of screening mammography. J Community Health. 2003;28(5):303–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1025451412007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshi M, et al. Differences in breast cancer screening rates: an issue of ethnicity or socioeconomics? J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(9):1025–1031. doi: 10.1089/15246090050200060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes-Ortiz CA, et al. The impact of education and literacy levels on cancer screening among older Latin American and Caribbean adults. Cancer Control. 2007;14(4):388–395. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambamoorthi U, McAlpine DD. Racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and access disparities in the use of preventive services among women. Prev Med. 2003;37(5):475–484. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goel MS, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hubbell FA, et al. From ethnography to intervention: developing a breast cancer control program for Latinas. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995;18:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Malley AS, et al. Acculturation and breast cancer screening among Hispanic women in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(2):219–227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Access and attitudinal factors related to breast and cervical cancer rescreening: why are Latinas still un-derscreened? Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(3):337–359. doi: 10.1177/1090198103030003008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez MA, Ward LM, Perez-Stable EJ. Breast and cervical cancer screening: impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):235–241. doi: 10.1370/afm.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suarez L. Pap smear and mammogram screening in Mexican-American women: the effects of acculturation. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(5):742–746. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valdez A, et al. Correlates of breast cancer screening among lowincome, low-education Latinas. Prev Med. 2001;33(5):495–502. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis TC, et al. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996;78(9):1912–1920. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961101)78:9<1912::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donelle L, Arocha JF, Hoffman-Goetz L. Health literacy and numeracy: key factors in cancer risk comprehension. Chronic Dis Can. 2008;29(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barroso J, et al. Comparison between African–American and white women in their beliefs about breast cancer and their health locus of control. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23(4):268–276. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borrayo EA, Guarnaccia CA. Differences in Mexican-born and U.S.-born women of Mexican descent regarding factors related to breast cancer screening behaviors. Health Care Women Int. 2000;21(7):599–613. doi: 10.1080/07399330050151842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niederdeppe J, Levy AG. Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention and three prevention behaviors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(5):998–1003. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chavez LR, et al. The influence of fatalism on self-reported use of Papanicolaou smears. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13(6):418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Florez KR, et al. Fatalism or destiny? A qualitative study and interpretative framework on dominican women’s breast cancer beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(4):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9118-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salazar MK. Hispanic women’s beliefs about breast cancer and mammography. Cancer Nurs. 1996;19(6):437–446. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schettino MR, et al. Assessing breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and misconceptions among Latinas in Houston, Texas. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1 Suppl):S42–S46. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Audrain J, et al. Awareness of heightened breast cancer risk among first-degree relatives of recently diagnosed breast cancer patients. The High Risk Breast Cancer Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4(5):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hubbell FA, et al. The influence of knowledge and attitudes about breast cancer on mammography use among Latinas and Anglo women. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(8):505–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Stable EJ, et al. Misconceptions about cancer among Latinos and Anglos. JAMA. 1992;268(22):3219–3223. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490220063029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storch EA, et al. The duke religion index: a psychometric investigation. Pastoral Psychol. 2004;53(2):175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magana A, Clark NM. Examining a paradox: does religiosity contribute to positive birth outcomes in Mexican American populations? Health Educ Q. 1995;22(1):96–109. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arredondo EM, et al. Is church attendance associated with Latinas’ health practices and self-reported health? Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(6):502–511. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Alba I, Impact of U.S, et al. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramirez AG, et al. Hispanic women’s breast and cervical cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(5):292–300. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hiatt RA, et al. Community-based cancer screening for underserved women: design and baseline findings from the Breast and Cervical Cancer Intervention Study. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):190–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Selvin E, Brett KM. Breast and cervical cancer screening: sociodemographic predictors among White, Black, and Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):618–623. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dominick KL, et al. Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(6):499–508. doi: 10.1007/BF03327351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zahran HS, et al. Health-related quality of life surveillance— United States, 1993–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54(4):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalez P, et al. Determinants of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening adherence in Mexican-American women. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):421–433. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9459-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andersen MR, et al. Breast cancer worry and mammography use by women with and without a family history in a population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hay JL, Buckley TR, Ostroff JS. The role of cancer worry in cancer screening: a theoretical and empirical review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2005;14(7):517–534. doi: 10.1002/pon.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Austin LT, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening in Hispanic women: a literature review using the health belief model. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12(3):122–128. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garbers S, et al. Barriers to breast cancer screening for lowincome Mexican and Dominican women in New York City. J Urban Health. 2003;80(1):81–91. doi: 10.1007/PL00022327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diefenbach MA, Miller SM, Daly MB. Specific worry about breast cancer predicts mammography use in women at risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Health Psychol. 1999;18(5):532–536. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCaul KD, et al. A descriptive study of breast cancer worry. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):565–579. doi: 10.1023/a:1018748712987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCaul KD, Schroeder DM, Reid PA. Breast cancer worry and screening: some prospective data. Health Psychol. 1996;15(6):430–433. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartz MD, Taylor KL, Willard KS. Prospective association between distress and mammography utilization among women with a family history of breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26(2):105–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023078521319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sadler GR, et al. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(3):369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire. 2007 (cited 2012 May 15). http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2007brfss.pdf.

- 71.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Appendix F: screening for breast cancer, guide to clinical preventive services, 2012, Clinical Summary of 2002 U.S. Preventive ServicesTaskForce Recommendation. 2012 (cited 2013 July 15). http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/guide/appendix-f.html.

- 72.Norris AE, Ford K, Bova CA. Psychometrics of a brief acculturation scale for Hispanics in a probability sample of urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1996;18(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Powe BD. Fatalism among elderly African Americans. Effects on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18(5):385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Powe BD. Cancer fatalism among elderly Caucasians and African Americans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1355–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lopez-McKee G, et al. Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Powe Fatalism inventory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(1):68–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andresen EM, et al. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(5):339–343. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gramling R, et al. The cancer worry chart: a single-item screening measure of worry about developing breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(6):593–597. doi: 10.1002/pon.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Afifi A, Clark VA, May S. Computer-aided multivariate analysis. 4th ed. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malcarne VL, Fernandez S, Flores L. Factorial validity of the multidimensional health locus of control scales for three American ethnic groups. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(5):657–667. doi: 10.1177/1359105305055311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kleinbaum DG, et al. Applied regression analysis and multivar-iable methods. 4th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Long JS. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Menard S. Applied logistic regression analysis. Quantitative applications in the social sciences: a Sage University paper. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guerra CE, Krumholz M, Shea JA. Literacy and knowledge, attitudes and behavior about mammography in Latinas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(1):152–166. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Breen N, Rao SR, Meissner HI. Immigration, health care access, and recent cancer tests among Mexican-Americans in California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):433–444. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.True S, et al. In conclusion: the promise of comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(Suppl 1):79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lucas JW. Theory-testing, generalization, and the problem of external validity. Sociol Theory. 2003;21(3):236–253. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Legler J, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sohl SJ, Moyer A. Tailored interventions to promote mammography screening: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Metsch LR, et al. The role of the physician as an information source on mammography. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(4):229–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006004229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Burger JM. The foot-in-the-door compliance procedure: a multiple-process analysis and review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 1999;3(4):303–325. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0304_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pascual A, Gueguen N. Foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face: a comparative meta-analytic study. Psychol Rep. 2005;96(1):122–128. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.1.122-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]