ABSTRACT

Approximately 30% of infants in the United States are exposed to high doses of isoflavones resulting from soy infant formula consumption. Soybeans contain the isoflavones genistin and daidzin, which are hydrolyzed in the gastrointestinal tract to their genistein and daidzein aglycones. Both aglycones possess hormonal activity and may interfere with male reproductive development. Testosterone, which supports male fertility, is mainly produced by testicular Leydig cells. Our previous studies indicated that perinatal exposure of male rats to isoflavones induced proliferative activity in Leydig cells and increased testosterone concentrations into adulthood. However, the relevance of the neonatal period as part of the perinatal window of isoflavone exposure remains to be established. The present study examined the effects of exposure to isoflavones on male offspring of dams maintained on a casein-based control or whole soybean diet in the neonatal period, that is, Days 2 to 21 postpartum. The results showed that the soybean diet stimulated proliferative activity in developing Leydig cells while suppressing their steroidogenic capacity in adulthood. In addition, isoflavone exposure decreased production of anti-Müllerian hormone by Sertoli cells. Similar to our previous in vitro studies of genistein action in Leydig cells, daidzein induced proliferation and interfered with signaling pathways to suppress steroidogenic activity. Overall, the data showed that the neonatal period is a sensitive window of exposure to isoflavones and support the view that both genistein and daidzein are responsible for biological effects associated with soy-based diets.

Keywords: androgen, androgens/androgen receptor, daidzein, endocrine disruptors, genistein, Leydig cells, phytoestrogen, sex steroids, testis, toxicology

Feeding of a soy-based diet in the neonatal period disrupted development of steroidogenic capacity and inhibited anti-Müllerian hormone protein expression in the rat testis.

INTRODUCTION

There is growing public concern that exposure of the population to natural and anthropogenic substances in food, water, and the environment may have deleterious effects on reproductive health. Chemicals that have the capacity to interfere with normal functioning of the endocrine system are designated as endocrine disruptors. For example, several reports have indicated that exposure to phytoestrogens found in soy and soy products interferes with reproductive development and cause anomalies of the male reproductive tract [1–3]. Soybeans predominantly contain a mixture of the isoflavones genistin and daidzin as the β-D-glycosides, which, following ingestion, are hydrolyzed by action of β-glucosidases to genistein and daidzein in the gastrointestinal tract [4]. Isoflavones have a nonsteroidal structure but possess a phenolic ring that enables them to bind estrogen receptors (ESRs) and thereby act as ESR agonists or antagonists [5, 6]. The mean isoflavone intake in breast-fed or cow milk formula-fed infants is 0.005–0.01 mg/day but amounts to 6–47 mg/day in soy formula-fed infants [7, 8]. Therefore, the consumption of soy-based infant formulas exposes infants to isoflavone concentrations several orders of magnitude greater than they receive from other dietary sources. Ingestion of high doses of isoflavones by neonates is of concern because exposure of male rats to high isoflavone concentrations affected testis development [9]. Also, other numerous bioactive compounds found in soybeans (i.e., phytic acids, soy protein, soybean oil) are known to regulate hormonal activity [10, 11].

A panel of experts commissioned by the National Toxicology Program to review the literature on soy isoflavones and their effects on the reproductive tract emphasized the lack of information on isoflavone exposures occurring in the neonatal period [12]. This is the case because most studies, to date, have focused on isoflavone exposures occurring in the continuous timespan of gestation, lactation, and the postweaning period. The continuous exposure paradigm makes it difficult to isolate specific effects associated with the neonatal period. Direct exposure of prepubertal animals to soy isoflavones during the neonatal period will be a suitable model for assessing effects of infant isoflavone exposure due to soy formula consumption [12]. Furthermore, the National Toxicology Program review noted that past studies of soy isoflavones have largely ignored the singular effects of daidzein [12]. This is a big omission because daidzin, which is the parent compound to daidzein, is a predominant isoflavone in soy formulas (∼29%–34%) [12]. Also, equol, a bioactive metabolite of daidzin, is known to exert hormonal activity [13].

Testicular Leydig cells are the predominant source of the male sex hormone testosterone (T), which supports the male phenotype. The development of adult Leydig cells begins by Postnatal Day (PND) 11 in the rat [14]. These cells, which are known as progenitor Leydig cells, divide actively between PND 14 and 28, and then transform into immature Leydig cells at about PND 35 [15]. Immature Leydig cells undergo a final round of cell division to become adult Leydig cells at 56 days of age [16]. Progenitor and immature Leydig cells have the capacity for active mitotic divisions, unlike adult Leydig cells, which are unable to divide but have full steroidogenic capacity [17]. Androgen synthesis in Leydig cells involves transport of the steroid substrate cholesterol from the outer to inner mitochondrial membrane by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). Cholesterol is subsequently converted into pregnenolone by the P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc/CYP11A1) [17]. Pregnenolone moves out of the mitochondria and into the smooth endoplasmic reticulum where it is acted upon, in succession, by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B), 17α-hydroxylase/C17-20 lyase (CYP17A1), and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (HSD17B3) to form progesterone, androstenedione, and T, respectively [17].

Whereas Leydig cells are mainly responsible for androgen production, Sertoli cells provide structural support and nutrition to developing germ cells [18]. In addition, Sertoli cells secrete several factors, including the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH; also known as Müllerian inhibiting substance [MIS]). AMH, a member of the transforming growth factor-β family and stimulates regression of the Müllerian ducts in male embryos [18]; however, its receptors, that is, type-II AMH receptors (AMHR2), are expressed in Sertoli cells and Leydig cells [19]. Thus, AMH acts as an autocrine as well as a paracrine regulator of testicular function due in part to interaction between testicular cells. There is evidence that estrogen-response elements are present in the promoter region of the Amh gene, implying that its expression is regulated by estrogen and ESR agonists [20].

The present study was designed to investigate the effects of neonatal exposures to isoflavones on testicular development and function. Animal studies were supplemented with in vitro experiments to confirm that observations of biological activity are due, at least in part, to the presence of genistin and daidzin in the soybean (SOY) diet. In addition, observations from in vitro experiments describe a role for daidzein in the regulation of Leydig cells and, hence, endocrine function of the testis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Housing

All the animal procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Auburn University. Time-bred Long-Evans dams, purchased from Harlan-Teklad and each weighing approximately 250 g, were allowed 3 days to acclimate in the housing facility of the Department of Laboratory Animal Health, College of Veterinary Medicine at Auburn University. Each dam was housed in a standard plastic cage (length, 0.47 m; width, 0.25 m; height, 0.22 m) containing wood chip bedding (Lab Products) and glass water bottles. Polypropylene cages and glass bottles were used in order to eliminate background exposure to estrogens, which may occur with polycarbonate cages [21]. Animals were housed under constant controlled lighting (12L:12D) and temperature (20°C–23°C) with free access to pelleted food and water.

Diets

Diets were formulated to contain casein (as control) or SOY. As determined by the manufacturer, the SOY diet contained 510 parts per million genistein and 430 parts per million daidzein based on its content of genistin and daidzin. Otherwise, both control casein and SOY diets were similar in their content of protein (19.5% vs. 22.8%), carbohydrate (50.4% vs. 45.8%), fat (5.5% vs. 5.6%), energy (3.3 kcal/g vs. 3.2 kcal/g), and micronutrients (Harlan-Teklad).

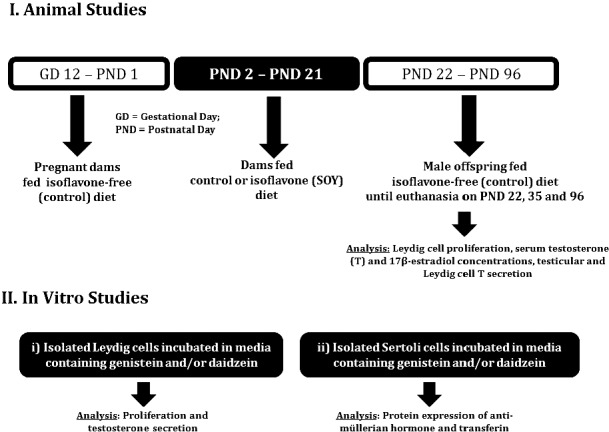

Animal Studies

Time-bred Long-Evans dams (n = 10, 11) were fed the control diet from Gestational Day 12 to PND 1 and were either continued on the control diet or were fed the SOY diet from PND 2 to PND 21, that is, during the neonatal period. Groups of male rats from control and SOY diet groups, selected randomly from each litter, were euthanized at 22, 35, and 96 days of age to assess testicular function: Leydig cell proliferation, serum T and 17β-estradiol (E2) concentrations, and testicular and Leydig cell T secretion (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the experimental approach. I) Time-bred Long-Evans dams (10 or 11 animals per group) were fed control diet from Gestational Day 12 to PND 1 and were either continued on the control diet or were fed the SOY diet from PND 2 to PND 21, that is, during the neonatal period. Groups of male rats from control and SOY diet groups, selected randomly from each litter, were killed at 22, 35, and 96 days of age to assess testicular function, that is, Leydig cell proliferation, serum T and 17β-estradiol (E2) concentrations, and testicular and Leydig cell T secretion. II) In vitro experiments were performed with Leydig cells isolated from 21- and 35-day-old male rats not previously exposed to dietary soy for incubation in media containing genistein and/or daidzein and Sertoli cells isolated from 9-day-old rats.

Measurement of Serum Isoflavone Concentrations

Serum was separated from blood collected at euthanasia from male weanling rats. The concentrations of total and free (aglycone) genistein, daidzein, and equol in serum were determined via liquid chromatography with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). The detection limit for total genistein, daidzein, and equol were 60, 40, and 150 nM, respectively, for a 10 μl sample. To determine aglycone concentrations, 100 μl samples were incubated overnight to achieve complete enzyme hydrolysis. The limits of detection for genistein, daidzein, and equol aglycones were 8, 4, and 17 nM, respectively. Samples that fell below the minimum level of detection were assigned a concentration of zero detection according to our standard protocol and as described previously [22].

Isolation of Testicular Cells

The procedure for isolating Leydig cells used at least 26 male rats from each group at PND 22, 14 animals at PND 35, and at least 13 adult rats at 96 days of age. Testes were collected after animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and were digested in a dissociation buffer containing 0.25 mg/ml collagenase, 46 μg/ml dispase, and 6 μg/ml DNase for 1 h in a shaking water bath at 34°C. Seminiferous tubules from immature testis were removed by passing testicular fractions through a nylon mesh (pore size, 0.2 μm; Spectrum Laboratories). The supernatant was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. In contrast, seminiferous tubules obtained from adult testis were removed by gravity sedimentation in dissociation buffer containing 10 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA). In every case, cell fractions were loaded onto a Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich) and then centrifuged at 13 500 rpm for 60 min at 4°C. Leydig cells were isolated from the Percoll gradient based on density, and their numbers were estimated using a hemocytometer. The purity of Leydig cell fractions was assessed by histochemical staining for HSD3B using 0.4 mM etiocholan-3β-ol-17-one (Sigma-Aldrich) as the enzyme substrate.

Sertoli cells were isolated from 9-day-old male rats that had not been previously exposed to isoflavones according to our usual protocol after they were killed by CO2 asphyxiation [23, 24]. Briefly, testes were decapsulated and subjected to sequential enzymatic digestion using a buffer containing 0.1% collagenase, 0.1% hyaluronidase, and 0.25% trypsin inhibitor (catalog no. T9003, Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.5% BSA to eliminate peritubular and Leydig cells. The resulting mixed cell suspension was trypsinized to eliminate clumps and resuspended in serum-free Dulbecco minimum essential media/Ham F-12 (DMEM/F-12) before culture at 37°C in matrigel-coated 12-well plates (Collaborative Research). This procedure results in Sertoli cell fractions with greater than 95% purity and preserves their functionality for at least 7 days [23, 24]. The media was changed after 4 h to remove spermatogonia followed by culture of Sertoli cells for 48 h prior to treatment with genistein and daidzein.

Analysis of Proliferative Activity

Proliferative activity in Leydig cells from 22- and 35-day-old male rats from both control and SOY diet groups was investigated by performing [3H] thymidine incorporation assays. Leydig cells were incubated in triplicate in culture medium containing 100 ng/ml of ovine LH and 1 μCi/ml of [3H] thymidine (specific activity: 80 Ci/mmol; DuPont-NEN Life Science Products). After labeling (3 h), Leydig cells were washed in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and then divided into aliquots of 0.5 × 106 cells for lysis in microcentrifuge tubes containing 500 μl of hyamine hydroxide (MP Biomedicals). The amount of [3H] thymidine uptake into Leydig cells was determined by scintillation counting (TRI-Carb 2900TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer; Packard Instrument Company). In addition, cyclin D3 expression was measured in Western blot analyses of Leydig cells not labeled with thymidine.

Measurement of Serum Steroid Hormones and Leydig Cell T Production

Serum was separated from trunk blood collected from male rats at euthanasia on PND 22, 35, and 96. Serum T and E2 levels were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA). Testicular parenchyma or explants (100 mg) and aliquots of Leydig cells (0.5–1 × 106) were incubated in microcentrifuge tubes. The culture medium consisted of DMEM/F-12 buffered with 14 mM NaHCO3 and 15 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) and contained 0.1% BSA (MP Biomedicals) and 0.5 mg/ml bovine lipoprotein (Perbio). Incubations were conducted with a maximally stimulating dose of 100 ng/ml ovine LH (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health) at 34°C for 3 h, and T concentrations were assayed in aliquots of spent media using a tritium-based RIA with an interassay variation of 7%–8% [25].

Analysis of AMH and AMHR2 Protein

The possibility that isoflavones interfere with paracrine regulators of testicular cells was investigated in male rats at 22 days of age by measurement of AMH and AMHR2 in Western blot analyses of testis and Leydig cells.

In Vitro Studies

Due to the possibility that dietary protein source (e.g., casein animal protein vs. soy plant protein) have the capacity, when acting on their own, to affect hormonal activity [25–27], primary Leydig cell cultures were incubated with genistein and daidzein to confirm that isoflavones acted directly in testicular cells independent of any action in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which are also targeted by endocrine disrupting chemicals [28]. In order to simulate the in vivo exposure paradigm, progenitor (PND 21) and immature Leydig cells (PND 35) were incubated in DMEM/F-12 culture medium containing equimolar concentrations (100 nM) of genistein and/or daidzein (Indofine Chemical Company). After treatment, Leydig cells were assessed for proliferative activity and steroid hormone secretion capacity. Second, concerns about the lack of information on biological effects of daidzein were addressed by incubation of Leydig cells in culture medium containing daidzein. Daidzein-treated Leydig cells were processed to measure proliferative capacity, steroid hormone secretion, and expression of steroidogenic proteins (Fig. 1). Third, neonatal Sertoli cells were isolated from isoflavone-free 9-day-old male rats and incubated with or without genistein and/or daidzein (0 or 100 nM, 24 h). At the end of the treatment period, expression of AMH and transferrin as markers of Sertoli cell differentiation were analyzed in Western blots (Fig. 1).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western Blot Analysis

Western blot procedures were performed as previously described [9]. Briefly, Leydig cell protein samples (5–15 μg) in Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) and 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) were loaded onto 10% Tris-HCl acrylamide gels for separation by SDS-PAGE and subsequently electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) for 70–90 min. In order to block nonspecific sites, membranes were incubated in 5% blotto (nonfat, dried milk in 0.1% PBS Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature (22°C–25°C) and subsequently overnight at 4°C in blotto containing primary antibodies: cyclin D3, (1:500), StAR (1:2000), HSD3B (1:1000), CYP17A1 (1:10 000), HSD17B3 (1:1000), AMH (1:1000), AMHR2 (1:2000), transferrin (1:1000), PCNA (1:500), Akt (1:250), p-AktSer473 (1:250), MAPK3/1 (1:250), p-MAPK3/1 (1:250), and β-actin (ACTB, 1:2000; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). After the Western blots were washed in 0.1% PBS Tween 20, antigen-antibody complexes were detected by incubation of the membranes with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) for 90 min at room temperature. In order to visualize bound secondary antibodies, membranes were incubated with a chemiluminescent developing reagent (Denville Scientific) for 1–2 min and then exposed to x-ray films for varying periods of time to establish linearity between exposure time and signal intensity (Denville Scientific). Protein bands were scanned using the Epson 4490 Perfection scanning software (Epson-America) and then quantified on the Doc-lt LS software (Ultra-Violet Products). Protein expression was normalized to β-actin, except for p-AktSer473 and p-MAPK3/1, which were normalized to corresponding total or inactive proteins.

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM except serum isoflavones (mean ± SD). Assays involving material collected from animal studies were performed three to five times. All in vitro experiments were performed on three separate and independent occasions. On each occasion, Leydig cell treatment was done in triplicate, and RIAs were performed in duplicate. T production was normalized to ng/106 Leydig cells. The data were analyzed by either one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test for multiple group comparisons or unpaired t-tests (Prism 4, GraphPad). Differences of P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Body weights (g) were similar (P > 0.05), measuring 10.2 ± 0.3 and 9.8 ± 0.3 at PND 5, 52 ± 1.3 and 52.3 ± 1.3 at PND 22, 139 ± 3.4 and 141 ± 3 at PND 35, and 465 ± 17 and 482 ± 13 at PND 96 in male rats from control and SOY diet groups, respectively.

Serum Isoflavone Concentrations

Serum isoflavone concentrations in 22-day-old weanling male rats from dams maintained on the SOY diet from PND 2 to PND 21 are shown in Table 1. As expected, genistein was not detected, and daidzein was below the detection limit in control unexposed animals. Genistein and daidzein were mostly present in their conjugated forms in serum and in the micromolar range, whereas unbound aglycones constituted a fraction of total isoflavones measured. For example, genistein was approximately 3% of total aglycones in the SOY diet group. Daidzein was present at greater concentrations in serum than genistein and approximated 5% of total aglycones in the SOY diet group. Measurements indicated that daidzein was converted into its metabolite equol, which was about 1% of total aglycones in the SOY diet group.

TABLE 1.

Serum concentrations of total and free isoflavones in 22-day-old male rats fed a SOY diet from Days 2–21 postpartum.a

N.D., not detectable; Free, aglycone

Number of samples with a measurable analyte concentration per total number of samples.

Neonatal Exposure to Isoflavones Increased Leydig Cell Proliferation and Decreased AMH Expression

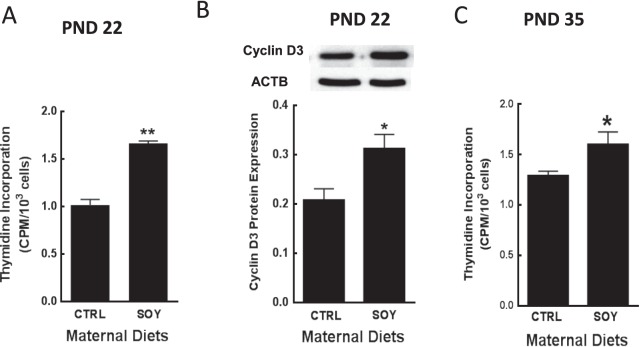

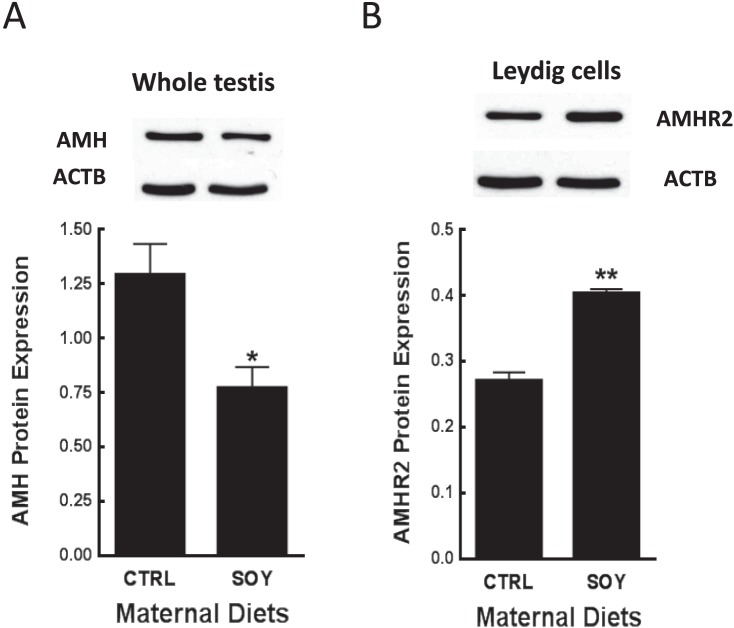

Paired testes weights (g) were similar (P > 0.05) and measured 0.24 ± 0.01 versus 0.26 ± 0.01 at PND 22, 1.11 ± 0.03 versus 1.17 ± 0.04 at PND 35, and 3.57 ± 0.15 versus 3.39 ± 0.08 at PND 96 in male rats from control and SOY diet groups, respectively. Body weights (g) were similar (P > 0.05) and measured 51.9 ± 1.3 versus 52.3 ± 1.3 at PND 22, 139 ± 3.4 versus 141 ± 3 at PND 35, and 465 ± 17 versus 482 ± 13 at PND 96 in male rats from control and SOY diet groups, respectively. Exposure to isoflavones in the neonatal period increased (P < 0.01) proliferation of Leydig cells in male rats at PND 22 and 35 compared to control (Fig. 2, A and C). The results of Western blot analysis showed that proliferative activity was related to greater expression (P < 0.05) of the cell cycle protein cyclin D3 in Leydig cells (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, testicular AMH expression per unit (μg) protein was decreased (P < 0.05) at 22 days of age after neonatal exposure of male rats to isoflavones compared to control (Fig. 3A). Conversely, AMHR2 protein was increased in Leydig cells from the SOY diet group compared to control (P < 0.01; Fig. 3B).

FIG. 2.

Leydig cells were isolated from male rats at 22 (26–28 animals per group) and 35 days of age (14–17 animals per group) after exposure to isoflavones in the neonatal period. Proliferative activity was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation and measured by liquid scintillation counting (A, C). Expression of cell cycle cyclin D3 was analyzed in Western blots of Leydig cells (PND 22) not labeled with [3H] thymidine (B). Cyclin D3 = 35 kDA, ACTB = 42 kDa. Proteins were normalized to ACTB, and the results are representative of densitometric analysis of three different assays. PND, postnatal day; CTRL, control; SOY, soy diet. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

FIG. 3.

Testis samples and Leydig cells were obtained from male rats at 22 days of age after exposure to isoflavones in the neonatal period as in Figure 1. AMH protein expression (A) was analyzed in testis homogenates (n = 6), whereas AMHR2 protein (B) was analyzed in Western blots of pooled Leydig cells. AMH = 63 kDa, AMHR2 = 63 kDa, ACTB = 42 kDa. Proteins were normalized to ACTB and results are representative of densitometric analysis of three different assays. CTRL, control; SOY, soy diet. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

Neonatal Exposure to Isoflavones Exerted Lasting Effects on Steroidogenic Capacity in the Testis

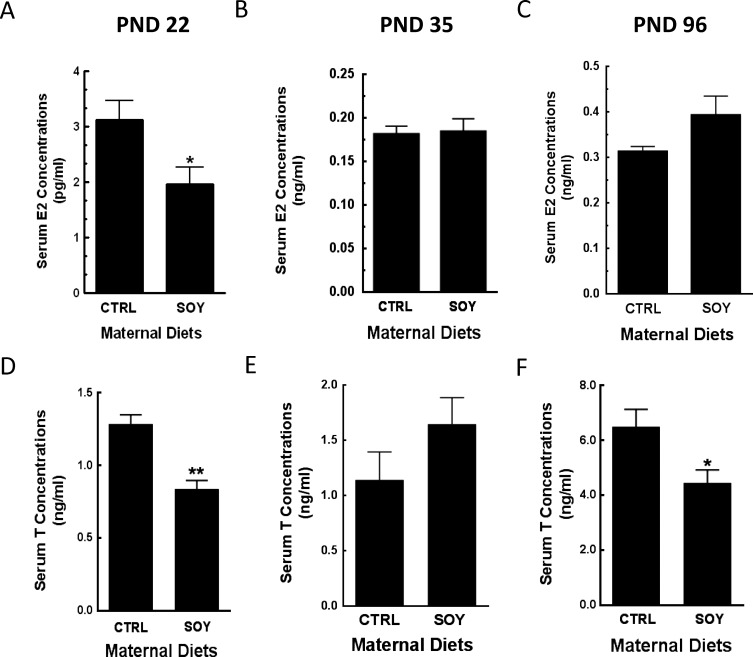

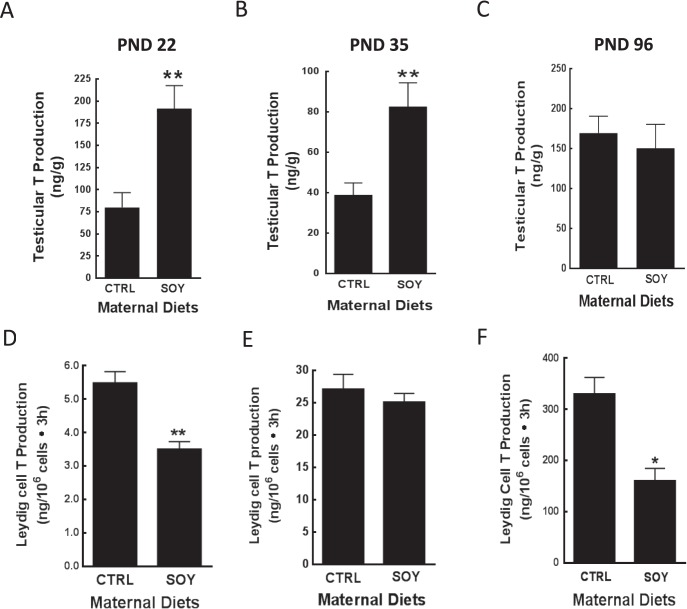

Serum E2 and T concentrations in male rats were decreased (P < 0.05) in the SOY diet group at 22 days of age compared to control (Fig. 4, A and D) but measurements were equivalent at 35 days (Fig. 4, B and E). There were no differences in serum E2 concentrations at 96 days of age but serum T concentrations were decreased (P < 0.05) in the SOY diet group compared to control (Fig. 4, C and F). Furthermore, testicular T production was increased (P < 0.05) in the SOY diet group at 22 and 35 but not at 96 days of age compared to control (Fig. 5A–C). In contrast, Leydig cell T secretion was decreased (P < 0.01) in the SOY diet group at 22 and 96 days of age but not at 35 days of age (Fig. 5D–F).

FIG. 4.

Serum was separated from blood after euthanasia of male rats at 22, 35, and 96 days of age after exposure to isoflavones in the neonatal period. Serum samples were assayed for 17β-estradiol (E2) (A–C) and testosterone (T) (D–F) concentrations by RIA. PND, postnatal day; CTRL, control; SOY, soy diet. Bars represent means ± SEM. * P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

FIG. 5.

Testicular explants and Leydig cells were obtained from male rats at 22, 35, and 96 days of age after exposure to isoflavones in the neonatal period. Testicular explants (A–C) and Leydig cells (D–F) were incubated in triplicate in culture medium containing ovine LH (100 ng/ml) and assayed for testosterone (T) secretion by RIA. PND, postnatal day; CTRL, control; SOY, soy diet. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

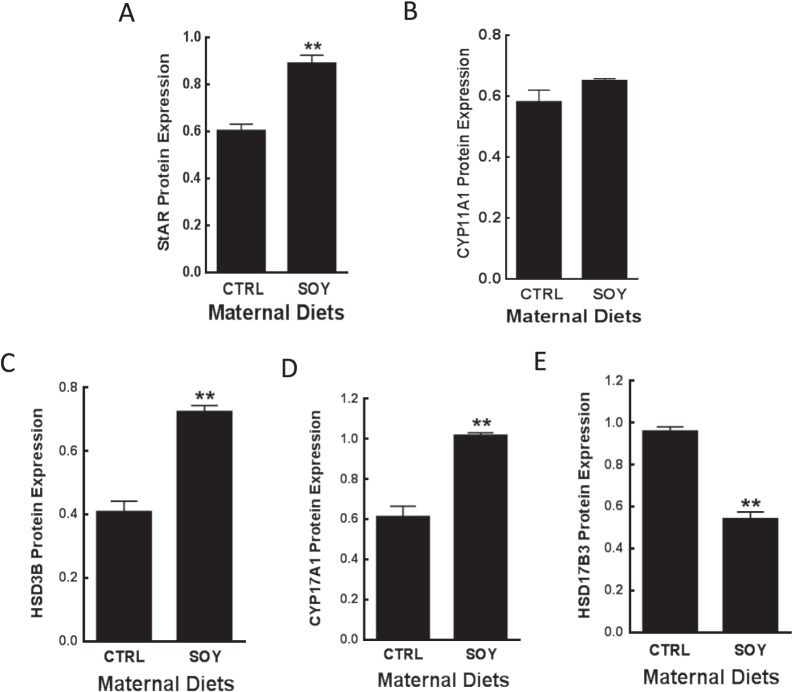

Analysis of the androgen biosynthetic pathway showed that HSD17B3 enzyme protein was decreased (P < 0.01) in the SOY diet group (Fig. 6E), which paralleled T production levels (Fig. 5F). However, expression of the StAR protein and other steroidogenic enzymes were either unaffected or increased (P < 0.05) in isoflavone-exposed animals compared to control (Fig. 6A–D).

FIG. 6.

Leydig cells, obtained at euthanasia from adult male rats (8–10 animals/group) exposed to isoflavones in the neonatal period were analyzed for expression of the StAR protein and steroidogenic enzymes by Western blot analysis using anti-StAR (A), anti-CYP11A1 (B), anti-HSD3B (C), anti-CYP17A1 (D), and anti-HSD17B3 (E) antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies. Protein concentrations were normalized to ACTB, and the data for each graph represent the results from at least three Western blot assays. CTRL, control; SOY, soy diet. Bars represent means ± SEM **P < 0.01 versus control.

Biological Effects Due to Exposure to Isoflavones In Vivo Are Similar to Observations In Vitro

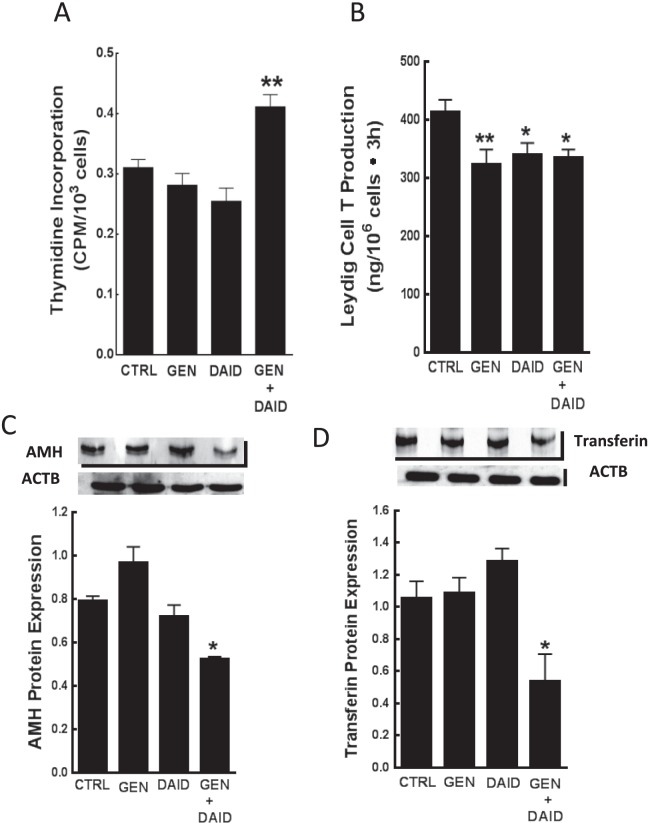

The results of in vitro experiments showed that incubation of Leydig cells isolated from isoflavone-free prepubertal male rats in culture medium containing genistein and daidzein (0, 100 nM, 18 h), but not genistein or daidzein at the same concentrations, increased (P < 0.01) proliferative activity in Leydig cells (Fig. 7A). Similarly, treatment of Leydig cells isolated from 35-day-old isoflavone-free male rats with genistein and/or daidzein (0, 100 nM, 18 h) decreased Leydig cell T secretion as measured in aliquots of spent media 3 h posttreatment (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, incubation of neonatal rat Sertoli cells with genistein and/or daidzein (0, 100 nM, 18 h), but not genistein or daidzein at same concentrations, had an inhibitory effect (P < 0.05) on AMH and transferrin protein expression (Fig. 7, C and D).

FIG. 7.

Leydig cells were isolated and pooled from isoflavone-free male rats at 21 days of age (n = 35) and incubated in culture medium containing ovine LH (10 ng/ml) and genistein (GEN) and/or daidzein (DAID) (100 nM, 18 h). After treatment, Leydig cells were analyzed for thymidine incorporation by scintillation counting (A). In separate experiments using Leydig cells pooled from 35-day-old male rats, Leydig cells were treated with GEN and/or DAID (18 h) and analyzed for T production 3h posttreatment by RIA (B). In addition, protein expression of AMH and transferrin were analyzed in primary cultures of Sertoli cells after incubation in culture medium containing GEN and/or DAID (100 nM, 18 h) (C, D). Protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis using anti-AMH and anti-transferrin antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies. The data represent the results of three separate and independent experiments and at least three Western blot procedures for each parameter per experiment. Protein levels were normalized to ACTB. AMH = 63 kDa, transferrin = 79 kDa, ACTB = 42 kDa. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

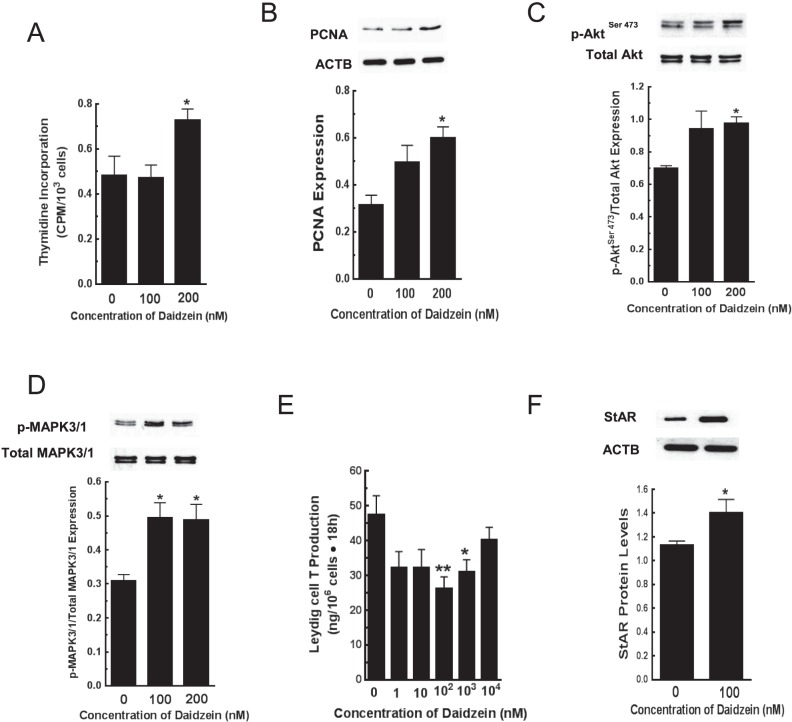

Daidzein Regulates Leydig Cell Function

Culture of Leydig cells isolated from isoflavone-free prepubertal male rats with daidzein (0, 100, or 200 nM; 18 h) increased (P < 0.05) cellular [3H] thymidine incorporation at 200 nM; this effect was associated with greater (P < 0.05) protein expression of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Fig. 8, A and B). Treatment with 200 nM daidzein caused greater activation of Akt on serine residue 473 (pAktSer473) and extracellular regulated kinase MAPK3/1 (p-MAPK3/1) compared to control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8, C and D). Similarly, incubation of developing Leydig cells in culture medium containing daidzein at 0, 1, 10, 102, 103, or 104 nM for 18 h decreased T secretion at 100 nM and 1 μM compared to control (P < 0.05; Fig. 8E). The decrease in androgen secretion was associated with greater (P < 0.05) StAR protein levels in Leydig cells (Fig. 8F), whereas steroidogenic enzyme proteins (i.e., CYP11A1, HSD3B, CYP17A1, and HSD17B3) were unaffected (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Leydig cells were isolated and pooled from isoflavone-free male rats at 21 days of age (n = 35). Proliferative activity was assessed by [3H] thymidine incorporation after incubation of Leydig cells in culture medium containing daidzein (0, 100, or 200 nM, 18 h) and ovine LH (10 ng/ml) (A). Expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (B) and protein kinase activation of protein kinase B (Akt) and extracellular regulated kinase (MAPK3/1) were analyzed in Western blots (C, D). In separate experiments, Leydig cells isolated from isoflavone-free 35-day-old male rats were incubated in culture medium containing daidzein (18 h) and ovine LH (100 ng/ml) followed by measurement of T secretion in aliquots of spent media by RIA (E). Leydig cells were processed for Western blot analysis of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) levels (F). PCNA and StAR protein were analyzed in Western blots of Leydig cells probed with anti-PCNA, anti-Akt, anti-p-AktSer473, anti-MAPK3/1, anti-p-MAPK3/1, and anti-StAR primary antibodies and the appropriate secondary antibodies. The data for each parameter represent the results from three separate and independent experiments and at least three Western blot procedures. PCNA and StAR protein were normalized to ACTB, whereas the levels of p-MAPK3/1 and p-AktSer473 were normalized to total MAPK3/1 and total Akt levels, respectively. PCNA = 35 kDa, AKT/p-AKTSer473 = 56/60 kDa, (p-) MAPK3/1 = 42/44 kDa, StAR = 30 kDa, ACTB = 42 kDa. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus control.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that exposure to soy isoflavones in the neonatal period increased proliferative activity in developing Leydig cells but exerted an opposite effect on steroid hormone secretion, that is, suppressed androgen concentration, in adult male rats. Androgen is an autocrine regulator of Leydig cells, which express the androgen receptor [29]. Therefore, it is possible that isoflavone inhibition of T secretion impairs or delays Leydig cell differentiation, which contributes to the observed decreases in androgen secretion. The neonatal period, albeit short in rodents, is thought to approximate the period during which infants are raised on soy-based formulas [30]. The concentrations of biologically active aglycones (i.e., free compounds) that were measured in the present study, that is, in the nanomolar range, compare to levels measured in infants consuming soy infant formula (∼300 nM) [8]. Although equol aglycone concentrations were generally low in serum (<1% of total equol), it measured at half the concentration of daidzein aglycone in the SOY diet group (92 ± 41 nM vs. 180 ± 100 nM). The presence of measurable amounts of equol in weanling male rats confirms that gut microflora required for reductive metabolism of daidzein to equol was already present in rats at 22 days of age. This finding is in agreement with previous reports indicating that about 30% of the human population and pubertal and older rats are able to degrade daidzein into equol [31, 32]. Therefore, it is likely that equol contributes to biological effects associated with consumption of soy-based food products as was previously reported [33]. However, exposure assessment in male rats subjected to the neonatal exposure paradigm as a basis for extrapolation to infants maintained on soy formulas presents several challenges because 1) the nursing period in rodents has a much shorter duration (21 days) compared to the period of infanthood in humans; 2) isoflavone secretion into milk is not substantial in rodents [34]; 3) nursing rats can feed on solid food from Day 10 postpartum and thereby ingest isoflavones through direct consumption in addition to what is transferred in milk; and 4) metabolic capacity is rudimentary early in the neonatal period although nursing male rats have developed similar capacity for isoflavone metabolism as adult rats by Day 21 postpartum [35]. For example, we observed previously that the mean estimated dose of genistein delivered to pups via milk was approximately 3100-fold lower than the mean dose delivered by maternal diet [34]. Therefore, serum isoflavone concentrations measured at weaning in the present study likely reflects isoflavone intake through both nursing and solid food intake [36].

The present findings of reduced serum E2 and T concentrations in 22- and 96-day-old rats, respectively, contrasts with previous observations of increased serum steroid hormone production in similarly aged animals under the perinatal exposure paradigm [9]. There is general consensus that serum sex hormone concentrations depend not only on steroidogenic capacity but also on the number of Leydig cells [37]. Although increased proliferation was observed under both exposure paradigms, we did not quantify Leydig cell numbers in the present study. Nevertheless, it is likely that greater Leydig cell populations result from the longer duration of perinatal (30 days) than for neonatal isoflavone exposures (20 days). On the other hand, it is possible that increased proliferative activity by Leydig cells did not increase their numbers to a degree that completely alleviated deficits in androgen secretion in the present study. Furthermore, it is perhaps reasonable to speculate that lower serum E2 concentrations in neonatal male rats in the SOY diet group is in part the consequence of altered aromatase activity, which is required to convert T into E2. While not investigated in the present study, other reports have shown that genistein and daidzein can inhibit aromatase expression in granulosa-luteal cells in the human ovary [38]. Therefore, the finding of decreased serum E2 levels has implications for germ cell development as was seen in aromatase-deficient mice [39, 40]. However, neonatal exposure to soy isoflavones increased Leydig cell proliferation as was observed in 22-day-old rats exposed to soy isoflavones during the perinatal period [9]. Therefore, it is likely that disparities in testicular and Leydig cell T production in growing rats are related to changes in Leydig cell numbers in the testis.

Neonatal exposure to soy isoflavones affected development of steroidogenic capacity as evidenced by altered StAR and steroidogenic enzyme protein levels in adult Leydig cells. Although StAR protein was paradoxically increased in the presence of decreased T production, augmented StAR protein levels are likely due to decreased LH stimulation and reduced StAR phosphorylation, which is critical for translocation of cytosolic cholesterol into the mitochondria [9, 41]. Importantly, neonatal exposure to isoflavones markedly decreased expression of the HSD17B3 enzyme protein; this enzyme is involved in the enzymatic conversion of androstenedione to T in the final step of androgen biosynthesis. Although serum LH levels were not assayed in the present study, decreased HSD17B3 expression has been attributed to reduced LH stimulation of Leydig cells as was evident in testis of hypogonadal and testicular feminized (tfm) mice [42]. Therefore, the observed increases in HSD3B and CYP17A1 protein expression were probably due to homeostatic adjustments provoked by diminished LH stimulation of cholesterol availability and/or utilization in Leydig cells.

Expression of AMH and transferrin was decreased by isoflavones in vivo and in vitro, indicating that isoflavones regulate Sertoli cells. It is plausible that isoflavone inhibition of the AMH protein was a contributing factor to increased proliferative activity in Leydig cells. This inference is supported by previous findings showing that AMH-overexpressing mice exhibited reduced Leydig cell numbers [40], whereas AMH-deficient mice developed Leydig cell hyperplasia [43–45]. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that AMH expression can be up-regulated or inhibited by estrogen depending on the ESR subtype predominant in estrogen-sensitive tissues. However, rat Leydig cells express only ESR1 [37], and AMH expression was also decreased in human granulosa cells of growing follicles, which express mostly ESR2, following E2 hyperstimulation [20]. Similarly, treatment of Sertoli cells with genistein and daidzein decreased transferrin protein expression levels. Transferrin is a marker of Sertoli cell differentiation and serves to deliver Fe2+ ions to spermatocytes during spermatogenesis [46, 47]. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of soy isoflavones in Sertoli cells may disrupt germ cell development and sperm production. Indeed, previous reports showed that feeding of adult Wistar male rats with a high phytoestrogen diet (i.e., 225 μg/g genistein and 180 μg/g daidzein) over a period of 24 days disrupted spermatogenesis and increased germ cell apoptosis [48]. We observed previously that the industrial chemical and xenoestrogen bisphenol A exerted a similar inhibitory effect on AMH secretion by Sertoli cells [49]. Furthermore, the finding of decreased AMH and transferrin protein expression by Sertoli cells implies that the effects of soy-based diets potentially occur in multiple cells in the testis. If that were the case, isoflavones likely cause effects greater than results of assays of individual cell types suggest.

Although genistein and daidzein are both known to be estrogenic [5, 6], the present study did not establish that biological effects due to isoflavones were necessarily mediated by ESRs. However, our findings are consistent with several reports in the literature. For example, plasma T concentrations were decreased after exposure of male rats to 5 or 300 mg/kg genistein in the diet during the perinatal period compared to control animals maintained on isoflavone-free diets [3] as well as in neonatal male rats that were subcutaneously administered with microgram amounts of the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol [50]. Similar to developmental exposures, feeding of a phytoestrogen diet (600 μg/g) containing mostly genistin and daidzin to adult male rats for 5 wk had a suppressive effect on serum T concentrations [51]. In studies of nonhuman primates, marmoset monkeys fed with 1.6–3.5 mg/kg/day isoflavones from Days 4–5 postpartum until 35–45 days of age, which is similar to the feeding of a 100% soy formula diet to 4-mo-old human infants, exhibited reduced T concentrations at 6 wk of age compared to age-matched controls maintained on cow milk formula [2]. However, these observations were challenged by the possibility that numerous bioactive substances found in soybean meal (i.e., glycetin and phytic acids) have the capacity to alter sex steroid metabolism [10, 11]. Also, soy protein was credited with the capacity to regulate thyroxine metabolism, which potentially affects steroidogenic capacity in Leydig cells [52, 53]. In the present study, we attempted to eliminate these confounders by demonstrating direct genistein and daidzein effects on testicular parameters using Leydig cells isolated from animals not previously exposed to isoflavones.

The present results confirmed that genistein and daidzein are both capable of regulating Leydig cells and support our previous observation of direct genistein action in Leydig cells [9]. The data also demonstrated that incubation with daidzein induced proliferative activity and suppressed steroidogenic capacity in Leydig cells. It appears that genistein and daidzein share signaling pathways in their regulation of Leydig cells because, similar to genistein [9], daidzein treatment activated protein kinases (i.e., Akt, MAPK). Moreover, and based on reports indicating that the S-equol metabolite binds to ESRs with higher affinity than daidzein [13], analysis of the effects of equol on Leydig cell development and testicular function warrants further attention and investigation. These results imply that additive effects may occur after exposure to multiple chemicals that act by the same signaling pathways. For example, increased proliferation of progenitor Leydig cells occurred after incubation with genistein and daidzein but not genistein or daidzein alone at the same concentrations. Pharmacokinetic interactions between chemicals may also occur to alter the biological action of constituent chemicals [54]. Interestingly, we observed a nonlinear dose inhibition of T secretion by daidzein. Nonmonotonic dose-response curves are typical of estrogenic compounds and have been described for several endocrine disruptors. For example, adult male rats exposed to 5 parts per million genistein during the perinatal period had smaller serum T concentrations than rats exposed to the 300 parts per million concentration [3]. The mechanisms responsible for nonmonotonic dose-response curves remain to be clarified but are thought to be related to ESR biology. Because low receptor occupancy appears to be adequate to induce ESR signaling, it is possible that effects of estrogenic compounds at high doses result from a combination of receptor- and nonreceptor-mediated activities [55, 56].

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate that feeding of soy-based diets during development potentially disrupts gonadal development. Given the interactions that occur between regulatory pathways in the reproductive axis, additional studies are required to identify long-term effects of the use of soy-based food products on reproductive tract development to support the process of risk assessment of the population.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant ES 15886 to B.T.A. E.S. was supported by a fellowship from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, administered through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Data were presented in preliminary form at the 46th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction, July 31–August 4, 2011, Portland OR.

REFERENCES

- Akingbemi BT, Braden TD, Kemppainen BW, Hancock KD, Sherrill JD, Cook SJ, He X, Supko JG. Exposure to phytoestrogens in the perinatal period affects androgen secretion by testicular Leydig cells in the adult rat. Endocrinology 2007; 148: 4475–4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe RM, Martin B, Morris K, Greig I, McKinnell C, McNeilly AS, Walker M. Infant feeding with soy formula milk: effects on the testis and on blood testosterone levels in marmoset monkeys during the period of neonatal testicular activity. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 1692–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski AB, Klein SL, Lakshmanan Y, Gearhart JP. Exposure to genistein during gestation and lactation demasculinizes the reproductive system in rats. J Urol 2003; 169: 1582–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S. The biochemistry, chemistry and physiology of the isoflavones in soybeans and their food products. Lymphat Res Biol 2010; 8: 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela S, Davis VL, Tally WC, Korkman J, Salo L, Vihko R, Santti R, Korach KS. Dietary estrogens act through estrogen receptor-mediated processes and show no antiestrogenicity in cultured breast cancer cells. Environ Health Perspect 1994; 102: 572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela SI, Pylkkanen LH, Santti RS, Adlercreutz H. Dietary soybean may be antiestrogenic in male mice. J Nutr 1995; 125: 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger TM, Ronis MJ, Hakkak R, Rowlands JC, Korourian S. The health consequences of early soy consumption. J Nutr 2002; 132: 559s–565s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Zimmer-Nechemias L, Cai J, Heubi JE. Exposure of infants to phyto-oestrogens from soy-based infant formula. Lancet 1997; 350: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill JD, Sparks M, Dennis J, Mansour M, Kemppainen BW, Bartol FF, Morrison EE, Akingbemi BT. Developmental exposures of male rats to soy isoflavones impact Leydig cell differentiation. Biol Reprod 2010; 83: 488–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey MJ, Cooke GM, Curran IH, Chan HM, Kubow S, Lok E, Mehta R. Effects of dietary fats and proteins on rat testicular steroidogenic enzymes and serum testosterone levels. Food Chem Toxicol 2008; 46: 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzechowski A, Ostaszewski P, Jank M, Berwid SJ. Bioactive substances of plant origin in food—impact on genomics. Reprod Nutr Dev 2002; 42: 461–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarver G, Bhatia J, Chambers C, Clarke R, Etzel R, Foster W, Hoyer P, Leeder JS, Peters JM, Rissman E, Rybak M, Sherman C, et al. NTP-CERHR expert panel report on the developmental toxicity of soy infant formula. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 2011; 92: 421–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morito K, Hirose T, Kinjo J, Hirakawa T, Okawa M, Nohara T, Ogawa S, Inoue S, Muramatsu M, Masamune Y. Interaction of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Biol Pharm Bull 2001; 24: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyaratne HB, Mendis-Handagama SM, Mason JI. Effects of tri-iodothyronine on testicular interstitial cells and androgen secretory capacity of the prepubertal rat. Biol Reprod 2000; 63: 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge RS, Dong Q, Sottas CM, Papadopoulos V, Zirkin BR, Hardy MP. In search of rat stem Leydig cells: identification, isolation, and lineage-specific development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103: 2719–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ge RS, Zirkin BR. Leydig cells: from stem cells to aging. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009; 306: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AH, Hales DB. Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocr Rev 2004; 25: 947–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Clemente N, Belville C. Anti-Mullerian hormone receptor defect. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 20: 599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Seah CC, Masiakos PT, Sottas CM, Preffer FI, Donahoe PK, Maclaughlin DT, Hardy MP. Mullerian-inhibiting substance type II receptor expression and function in purified rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology 1999; 140: 2819–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynberg M, Pierre A, Rey R, Leclerc A, Arouche N, Hesters L, Catteau-Jonard S, Frydman R, Picard JY, Fanchin R, Veitia R, di Clemente N, et al. Differential regulation of ovarian anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) by estradiol through alpha- and beta-estrogen receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: E1649–E1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou JW, Collins DC, Schleicher RL. Sources of cholesterol for testosterone biosynthesis in murine Leydig cells. Endocrinology 1990; 127: 2047–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twaddle NC, Churchwell MI, Doerge DR. High-throughput quantification of soy isoflavones in human and rodent blood using liquid chromatography with electrospray mass spectrometry and tandem mass spectrometry detection. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2002; 777: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke PS, Zhao YD, Bunick D. Triiodothyronine inhibits proliferation and stimulates differentiation of cultured neonatal Sertoli cells: possible mechanism for increased adult testis weight and sperm production induced by neonatal goitrogen treatment. Biol Reprod 1994; 51: 1000–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl AF, Griswold MD. Sertoli cells of the testis: preparation of cell cultures and effects of retinoids. Methods Enzymol 1990; 190: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran RC, Ewing LL, Niswender GD. Serum levels of follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, testosterone, 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone, 5 alpha-androstane-3 alpha, 17 beta-diol, 5 alpha-androstane-3 beta, 17 beta-diol, and 17 beta-estradiol from male beagles with spontaneous or induced benign prostatic hyperplasia. Invest Urol 1981; 19: 142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Wood C, L'Abbe MR, Gilani GS, Cockell KA, Xiao CW. Soy protein isolate increases hepatic thyroid hormone receptor content and inhibits its binding to target genes in rats. J Nutr 2005; 135: 1631–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmen FA, Mercado CP, Zavacki AM, Huang SA, Greenway AD, Kang P, Bowman MT, Prior RL. Soy protein diet alters expression of hepatic genes regulating fatty acid and thyroid hormone metabolism in the male rat. J Nutr Biochem 2010; 21: 1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DL, Mitchner NA, Uveges TE, Nephew KP, Khan S, Ben-Jonathan N. Cell-specific induction of c-fos expression in the pituitary gland by estrogen. Endocrinology 1997; 138: 2128–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Johnston H, Willerton L, Baker PJ. Failure of normal adult Leydig cell development in androgen-receptor-deficient mice. J Cell Sci 2002; 115: 3491–3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster WG, Chan S, Platt L, Hughes CL., Jr. Detection of phytoestrogens in samples of second trimester human amniotic fluid. Toxicol Lett 2002; 129: 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerge DR, Vanlandingham M, Twaddle NC, Delclos KB. Lactational transfer of bisphenol A in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Lett 2010; 199: 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy NV, Parkinson HD, Sochaski MA, Borghoff SJ. Kinetics of genistein and its conjugated metabolites in pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats following single and repeated genistein administration. Toxicol Sci 2006; 90: 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Brown NM, Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol—a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr 2002; 132: 3577–3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerge DR, Twaddle NC, Churchwell MI, Newbold RR, Delclos KB. Lactational transfer of the soy isoflavone, genistein, in Sprague-Dawley rats consuming dietary genistein. Reprod Toxicol 2006; 21: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerge DR, Churchwell MI, Chang HC, Newbold RR, Delclos KB. Placental transfer of the soy isoflavone genistein following dietary and gavage administration to Sprague Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol 2001; 15: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen S, Boberg J, Axelstad M, Dalgaard M, Vinggaard AM, Metzdorff SB, Hass U. Low-dose perinatal exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces anti-androgenic effects in male rats. Reprod Toxicol 2010; 30: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton L, Shan LX, Hardy MP. Differentiation of adult Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1995; 53: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice S, Mason HD, Whitehead SA. Phytoestrogens and their low dose combinations inhibit mRNA expression and activity of aromatase in human granulosa-luteal cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2006; 101: 216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CR, Graves KH, Parlow AF, Simpson ER. Characterization of mice deficient in aromatase (ArKO) because of targeted disruption of the cyp19 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 6965–6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KM, O'Donnell L, Jones ME, Meachem SJ, Boon WC, Fisher CR, Graves KH, McLachlan RI, Simpson ER. Impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking a functional aromatase (cyp 19) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 7986–7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock KD, Coleman ES, Tao YX, Morrison EE, Braden TD, Kemppainen BW, Akingbemi BT. Genistein decreases androgen biosynthesis in rat Leydig cells by interference with luteinizing hormone-dependent signaling. Toxicol Lett 2009; 184: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Yates MM, Walker VR, Korach KS. Characterization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in estrogen receptor (ER) null mice reveals hypergonadism and endocrine sex reversal in females lacking ERalpha but not ERbeta. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17: 1039–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine C, Rey R, Forest MG, Louis F, Ferre A, Huhtaniemi I, Josso N, di Clemente N. Receptors for anti-mullerian hormone on Leydig cells are responsible for its effects on steroidogenesis and cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 594–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salva A, Hardy MP, Wu XF, Sottas CM, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK, Lee MM. Mullerian-inhibiting substance inhibits rat Leydig cell regeneration after ethylene dimethanesulphonate ablation. Biol Reprod 2004; 70: 600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Arumugam R, Baker SP, Lee MM. Pubertal and adult Leydig cell function in Mullerian inhibiting substance-deficient mice. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger P. The organization and function of the male reproductive system. : Senger P. (ed.), Pathways to Pregnancy and Parturition, 2nd revised ed. Pullman, WA: Current Conceptions, Inc.; 2003: 44–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM. MIS actions in the developing testis. : Goldberg E. (ed.), The Testis. New York: Springer; 2000: 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Assinder S, Davis R, Fenwick M, Glover A. Adult-only exposure of male rats to a diet of high phytoestrogen content increases apoptosis of meiotic and post-meiotic germ cells. Reproduction 2007; 133: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa MK, Simon L, Akingbemi BT. The industrial chemical bisphenol A (BPA) interferes with proliferative activity and development of steroidogenic capacity in rat Leydig cells. Biol Reprod 2012; 86: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal HO, Robateau A, Braden TD, Williams CS, Srivastava KK, Ali K. Neonatal estrogen exposure of male rats alters reproductive functions at adulthood. Biol Reprod 2003; 68: 2081–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KS, Setchell KD, Stocco DM, Lephart ED. Dietary soy-phytoestrogens decrease testosterone levels and prostate weight without altering LH, prostate 5alpha-reductase or testicular steroidogenic acute regulatory peptide levels in adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. J Endocrinol 2001; 170: 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony FF, Aruldhas MM, Udhayakumar RC, Maran RR, Govindarajulu P. Inhibition of Leydig cell activity in vivo and in vitro in hypothyroid rats. J Endocrinol 1995; 144: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MP, Kirby JD, Hess RA, Cooke PS. Leydig cells increase their numbers but decline in steroidogenic function in the adult rat after neonatal hypothyroidism. Endocrinology 1993; 132: 2417–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan YM, Clewell H, Campbell J, Andersen M. Evaluating pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions with computational models in supporting cumulative risk assessment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011; 8: 1613–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol 2005; 19: 1951–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel SC, vom Saal FS, Thayer KA, Dhar MG, Boechler M, Welshons WV. Relative binding affinity-serum modified access (RBA-SMA) assay predicts the relative in vivo bioactivity of the xenoestrogens bisphenol A and octylphenol. Environ Health Perspect 1997; 105: 70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]