Abstract

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is associated with fibrotic diseases in the lens, such as anterior subcapsular cataract (ASC) formation. Often mediated by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, EMT in the lens involves the transformation of lens epithelial cells into a multilayering of myofibroblasts, which manifest as plaques beneath the lens capsule. TGF-β–induced EMT and ASC have been associated with the up-regulation of two matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs): MMP-2 and MMP-9. The current study used MMP-2 and MMP-9 knockout (KO) mice to further determine their unique roles in TGF-β–induced ASC formation. Adenoviral injection of active TGF-β1 into the anterior chamber of all wild-type and MMP-2 KO mice led to the formation of distinct ASC plaques that were positive for α-smooth muscle actin, a marker of EMT. In contrast, only a small proportion of the MMP-9 KO eyes injected with adenovirus-expressing TGF-β1 exhibited ASC plaques. Isolated lens epithelial explants from wild-type and MMP-2 KO mice that were treated with TGF-β exhibited features indicative of EMT, whereas those from MMP-9 KO mice did not acquire a mesenchymal phenotype. MMP-9 KO mice were further bred onto a TGF-β1 transgenic mouse line that exhibits severe ASC formation, but shows a resistance to ASC formation in the absence of MMP-9. These findings suggest that MMP-9 expression is more critical than MMP-2 in mediating TGF-β–induced ASC formation.

A cataract is an opacity that forms in the lens and is characterized by an increase in light scatter and a loss of lens transparency. Cataract is the leading cause of blindness worldwide despite the availability of effective surgery in developed countries.1,2 According to the World Health Organization, up to 39 million people are blind worldwide, and of these, 51% of them are blind because of cataract; 65% of blind people are older than 50 years.2,3 Treatment involves surgical removal of the cataractous lens, replacing it with a synthetic intraocular lens. Although this offers quick restoration of vision, it is the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the developed world, with approximately 3 million operations performed in the United States per year,4 carrying a cost of $3.4 billion.5 Cataract surgery can also lead to a number of complications, the most common of which is secondary cataract, also known as, posterior capsular opacification (PCO).6–10

PCO is considered to be a proliferative fibrotic disorder that is characterized by aberrant extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and wrinkling of the posterior lens capsule. Another related type of fibrotic cataract is anterior subcapsular cataract (ASC). ASC is a primary cataract that develops after a pathologic insult, such as ocular trauma or surgery, or systemically, as with diseases such as atopic dermatitis and retinitis pigmentosa. In ASC, the monolayer of epithelial cells on the anterior surface of the lens [lens epithelial cells (LECs)] is triggered to proliferate and transform into large spindle-shaped cells, or myofibroblasts, through a phenomenon known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).11–13 These myofibroblasts form fibrotic plaques beneath the anterior lens capsule and express contractile elements, such as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Similar to ASC, during PCO, a proportion of LECs, which remain within the capsule after cataract surgery, are triggered to proliferate and migrate to the posterior lens capsule, where they undergo EMT into myofibroblasts and contribute to capsular wrinkling and aberrant matrix deposition.7,11,13 Recent evidence has suggested that the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes involved in remodeling the ECM, play an important role in the development of both of these fibrotic cataract phenotypes.

MMPs are a family of >25 genetically distinct but structurally related zinc-dependent matrix degrading enzymes that participate in many physiologic processes, including embryogenesis and wound healing, and are implicated in fibrosis and a number of diseases.14–16 Although they are principally known for their role in ECM remodeling, additional roles for MMPs have recently emerged, including their ability to regulate cell migration, invasion, and cell signaling, as well as EMT in multiple tissues.17,18 Accumulating studies have demonstrated that the expression of specific MMPs is induced in a variety of cataract phenotypes, including ASC and PCO,16 as well as others, such as posterior subcapsular cataracts.19 Furthermore, inhibition of MMP activity through the use of broad MMP inhibitors, such as GM6001 or EDTA, and specific MMP inhibitors have been reported to suppress cellular features known to contribute to ASC and PCO, such as lens epithelial cell migration, EMT, and capsular bag contraction.16,20,21

In particular, the gelatinases, MMP-2 and MMP-9, have been implicated in ASC and PCO, and a significant induction in their secretion was found to occur in a rodent model of ASC after treatment with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.22,23 TGF-β has been reported to play a pivotal role in ASC and PCO. In the anterior chamber of the eye, latent TGF-β is a normal constituent of the aqueous humor, which bathes and nourishes the lens.24 Activation of TGF-β ligands, after injury, results in the recruitment of an active TGF-β receptor tetramer capable of signal transduction, which initiates EMT. Indeed, a number of in vitro and in vivo models have found that addition of active TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 induces EMT in the lens and results in ASC formation, which closely mimics human ASC.23,25–27 Using the excised rat lens model of ASC, our laboratory has found that co-treatment of lenses with active TGF-β and either of two commercially available MMP inhibitors, GM6001, a broad MMP inhibitor, or a MMP-2/9–specific inhibitor, significantly suppressed both EMT and subsequent ASC formation.23 These data demonstrated, for the first time to our knowledge, that inhibition of these specific MMPs could block ASC formation in a whole (excised) lens and further indicate the requirement for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the EMT of LECs.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 are closely related MMPs that degrade basement membrane components and are considered to have some redundant and cooperative roles during development and disease. For example, in MMP-2/MMP-9 double knockout (KO) mice both the incidence and the severity of choroidal neovascularization (which leads to age-related macular degeneration) were strongly attenuated compared with single-gene deficient mice or corresponding wild-type controls.28 Additional studies in the lens revealed that during ASC formation MMP-9 mRNA is induced before MMP-2, and the addition of recombinant human MMP-9 to a human lens epithelial cell line, FHL-124, is able to induce MMP-2, along with the EMT marker α-SMA.22 Together these findings suggest that, of the two gelatinases, MMP-9 may play a more critical role in ASC formation. The unique roles that these MMPs play in ASC formation, however, have yet to be tested.

In the current study, we addressed the individual requirement(s) of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in ASC formation using two models of lens-specific TGF-β overexpression. Adenoviral delivery of TGF-β1 to the anterior chamber of the eye of MMP-2 and MMP-9 KO mice revealed that, although wild-type and MMP-2 KO mice formed distinct ASC plaques, virtually all of the MMP-9 KO eyes injected with adenovirus-expressing TGF-β1 (AdTGF-β1) did not. To further delineate a role for MMP-9 in ASC formation, MMP-9 KO mice were also bred onto a TGF-β1 transgenic, gain-of-function line that exhibits severe ASC formation. The MMP-9 KO mice also had substantial resistance to ASC formation in this model. Finally, lens epithelial explants isolated from MMP-2 and MMP-9 KO mice further demonstrated that, although wild-type and MMP-2 KO explants treated with TGF-β exhibited a loss in epithelial cell characteristics, MMP-9 KO explants did not. Overall, these findings suggest that of the two MMPs, MMP-9 expression is more critical in TGF-β–induced EMT and ASC formation.

Materials and Methods

Animal Studies

All animal studies were performed according to the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. MMP-2 KO mice (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX),29 and MMP-9 KO mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were on a C57BL/6 background and were generated by the removal of exon 1 of the Mmp2 gene and removal of part of exon 2 and all of intron 2 of the Mmp9 gene. In both cases, these regions were replaced with a pgk-neo gene cassette.30,31 TGF-β1 transgenic mice were obtained from Dr. Paul Overbeek (Baylor College of Medicine) and contain a porcine TGF-β1 cDNA construct with an αA-crystallin promoter designed for lens-specific expression of active TGF-β1 on a FVB/N/C57BL/6J genetic background.32 TGF-β transgenics were crossed with MMP-9 KO animals to generate TGF-β+/MMP-9+/− mice. The experimental animals were then created by breeding TGF-β+/MMP-9+/− with TGF-β−/MMP-9+/−. Wild-type littermates were used to account for the various differences among the strains of mice.

Genotype Analysis

DNA extraction and purification from mouse ear tissue were performed with a kit (DNeasy; Qiagen, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada). Genotypes were determined by PCR analysis. Mmp2 and Mmp9 wild-type and KO alleles were detected using the following primers. The Mmp2 wild-type allele was detected by using primers 5′-CAACGATGGAGGCACGAGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCGGGGAACTTGATGATGG-3′ (reverse) amplifying a 120-bp fragment. The Mmp2 KO allele was detected by using primers 5′-TGTATGTGATCTGGTTCTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGA-3′ (reverse) to yield a 1.1-kbp fragment. PCR reactions were performed for 35 cycles in the following conditions: initial heating for 2 minutes at 94.5°C, denaturation for 1 minute at 94.5°C, annealing for 1 minute at 57°C, and extension for 1.5 minutes at 72°C. A final extension was performed for 5 minutes at 72°C. The Mmp9 wild-type allele was detected by using primers 5′-GTGGGACCATCATAACATCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCGCGGCAAGTCTTCAGAGTA-3′ (reverse) amplifying a 277-bp fragment. The Mmp9 KO allele was detected by using primers 5′-CTGAATGAACTGCAGGCAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATACTTCTCGGCAGGAGCA-3′ (reverse) to yield a 172-bp fragment. PCR reactions were performed for 35 cycles in the following conditions: initial heating for 2 minutes at 94°C, denaturation for 30 seconds at 94°C, annealing for 30 seconds at 60°C, and extension for 2 minutes at 72°C. A final extension was performed for 10 minutes at 72°C. The TGF-β1 transgene was identified using primers specific for the simian virus 40 sequences in the transgene. The sense primer (5′-GTGAAGGAACCTTACTTCTGTGGTG-3′) and the antisense primer (5′-GTCCTTGGGGTCTTCTACCTTTCTC-3′) yield a 300-bp fragment. PCR reactions were performed for 36 cycles using the following conditions: initial heating for 3 minutes at 94°C, denaturation for 30 seconds at 94°C, annealing for 1 minute at 57°C, and extension for 1 minute at 72°C. A final extension was performed for 10 minutes at 72°C. Agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose) with ethidium bromide detection was used to visualize the PCR reaction products.

Recombinant Adenovirus

Biologically active porcine TGF-β1 was administered into the anterior chamber of mouse eyes in these studies using a previously validated adenoviral gene transfer method.33 To produce constitutively and biologically active TGF-β1 protein, TGF-β cDNA was mutated with two cysteine to serine point mutations at sites 223 and 225 (TGF-β223/225) located in the pro region of precursor TGF-β,34 preventing the resulting protein from binding to its latency-associated protein. This mutated cDNA was used to construct a recombinant, replication-deficient type 5 adenovirus, where the E1 region was replaced by the human cytomegalovirus promoter, driving the expression of TGF-β223/225 followed by the simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal.35 The resultant adenovirus (AdTGF-β) was amplified in 293 cells, purified by cesium chloride gradient centrifugation and concentrated using a Sephadex PD-10 chromatography column (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). An empty control adenoviral-delete vector (AdDL), with no insert in the deleted E1 region, was produced by similar methods.35

Adenoviral vectors were intracamerally injected into MMP-2 and MMP-9 wild-type and KO mice, as described previously.36,37 All animal procedures were performed with the animals under inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane (MTC Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, ON, Canada). AdTGF-β or AdDL at 5 × 108 PFU were injected in a volume of 5 μL in PBS. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed under a dissecting microscope to visualize general eye structures. Virus solution (5 μL) was administered into the anterior chamber of each mouse using a 33-gauge needle attached to a 10-μL Hamilton syringe. Eyes were covered with ophthalmic lubricating ointment (Lacrilube; Allergen, Irvine, CA) after injection, and animals were allowed to recover before returning to their cages. Animals were sacrificed 2 to 3 weeks after injection.

Ex Vivo Mouse Lens Epithelium Explants Preparation and Treatment

To obtain lens epithelial cell explants, 6- to 8-week-old MMP-2 and MMP-9 wild-type and KO mouse lenses were dissected and placed in 35-mm basement cell extract–coated (Trevigen, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) culture plates that contained prewarmed, serum-free medium M199, supplemented with antibiotics (Invitrogen, Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada). The lens was placed posterior side up, the posterior pole was gently torn, and the fiber mass was slowly removed, revealing the epithelium. Once separated, the epithelium is then pinned with a blunt tool to the bottom of the culture dish, with the LECs directly bathed by the medium and the outer lens capsule facing downward. Twenty-four hours after explanting, confluent mouse epithelial explants were left untreated in serum-free M199 or treated with TGF-β2 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) at 500 pg/mL for 48 hours.

Histologic Analysis and Immunofluorescence

AdTGF-β– or AdDL-injected (2 to 3 weeks after injection) or transgenic (1 to 3 months of age) mice were sacrificed and enucleated. Eyes were processed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and processed for routine histologic analysis. Midsagittal sections (4 μm) were stained with H&E or for immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of α-SMA. For α-SMA detection, paraffin sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated with 5% normal goat serum for 20 minutes at room temperature. Sections were incubated with mouse anti–α-SMA monoclonal antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich Co., Oakville, ON, Canada) at room temperature for 1 hour. All sections were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Inc., Eugene, OR) to visualize the nucleus. Staining was visualized with a Leica DMRA2 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems Canada, Inc., Richmond Hill, ON, Canada) equipped with a Q-Imaging RETIGA 1300i FAST digital camera (Q-Imaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). Images were captured using OpenLab software version 4.0 (PerkinElmer LAS, Shelton, CT). Images were reproduced for publication (Photoshop CS3; Adobe Systems, Inc., Mountain View, CA).

After 48 hours, untreated and treated mouse lens explants were fixed for 15 minutes with 10% neutral buffered formalin, then incubated at room temperature with the permeabilizer (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.5% SDS) and 5% donkey serum for 1 hour. Staining was performed overnight at 4°C with explants detached from the culture dish and left free-floating in a glass tube, with an anti–α-SMA fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated monoclonal antibody (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich Co., Oakville, ON, Canada), anti–E-cadherin mouse monoclonal antibody (1:200; BD Transduction Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada), and antiactive β-catenin (clone 8E7; EMD Millipore Corp, Temecula, CA). E-cadherin was visualized using a donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen, Inc.). After antibody incubation, the explants were washed repeatedly with PBS and mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI. Levels of α-SMA in stained explants were quantified using ImageJ quantification software version 1.44 (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Fluorescence was normalized to number of cells in each image and compared with control levels.

Western Blot Analysis

Lens epithelial explants isolated from MMP-9 wild-type and KO mice were collected for Western blot analysis of E-cadherin, as described previously.38 Five LEC explants per sample were homogenized in Triton-X 100 lysis buffer that contained protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Laval, QC, Canada). Total protein concentration of the lysates was determined using Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Equal amounts of total protein were loaded in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The resolved bands were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Corporation, East Hills, NY). Membranes were blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse anti–E-cadherin antibody (1:8000) and chicken polyclonal anti–β-tubulin III (1:8000; Abcam, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada). After the overnight incubation, membranes were washed repeatedly in PBS and probed with corresponding LI-COR IRDye secondary antibodies (1:10,000, LI-COR Biosciences). Blots were visualized using the LI-COR Odyssey imaging system, and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ quantification software.

E-Cadherin ELISA

Levels of E-cadherin were measured in the culture media of untreated and treated wild-type and MMP-9 KO LEC explants by using a mouse E-cadherin–specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Media from explant dishes (four to six explants per dish) was collected and concentrated. Standards and samples were applied to a microplate coated with rat anti-mouse E-cadherin recognizing the N-terminal domain of E-cadherin, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer protocol. The optical density of standards and samples was determined at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and E-cadherin protein concentrations were extrapolated from a standard curve.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM and were tested for significance by Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance where appropriate (SPSS statistical software version 22.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Tukey post hoc comparisons were performed when statistical significance (P < 0.05) was found among the observations.

Results

Delivery of AdTGF-β1 to the Anterior Chamber Results in ASC Formation in MMP-2 KO Mice But Not MMP-9 KO Mice

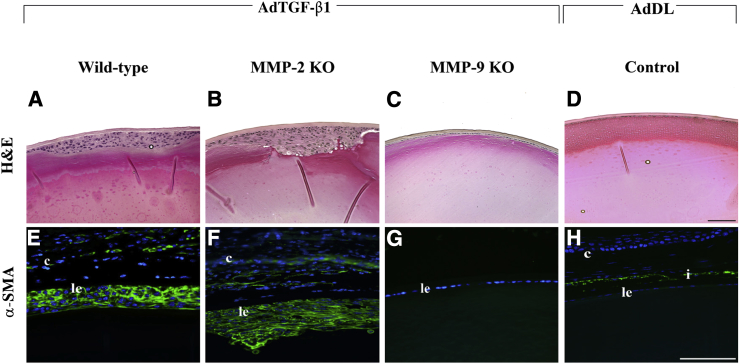

AdTGF-β injections for the delivery of genes into the lens have been previously validated by our laboratory37 through the injection of the reporter constructs adenoviral-LacZ and adenoviral-GFP into the anterior chamber of mouse eyes. Transgene expression was detected in the lens epithelium 4 days after injection in the absence of a capsular break, whereas transgene expression was absent in the lens epithelium of the AdDL injected eyes. In the current study, we used this approach with MMP-2 and MMP-9 KO mice and their wild-type littermates. One eye of each mouse was injected with AdTGF-β1, and the contralateral eye served as an uninjected control. Eyes from additional mice were also injected with AdDL vectors, which served as a control vector with no insert within the deleted E1 region. Two weeks after injection 100% of all wild-type mice treated with AdTGF-β1 exhibited distinct ASC plaques that consisted of a focal multilayering of LECs beneath the intact anterior lens capsule (Figure 1A). Each of the AdTGF-β1–treated eyes commonly exhibited one plaque, typically found in a central location of the anterior region of the lens. AdDL vectors did not induce any ASC features after injection into the wild-type eyes (Figure 1D). Similar to their wild-type littermates, all of the MMP-2 KO mice injected with AdTGF-β1 exhibited ASC formation (Figure 1B). The ASC plaques in the MMP-2 KOs were also comparable in size and location to their wild-type controls. Importantly, in contrast to both wild-type and MMP-2 KO eyes, delivery of active AdTGF-β1 to the anterior eye chamber of MMP-9 KO mice resulted in significant resistance to ASC formation (Figure 1C). Of the 11 treated eyes examined, only one exhibited a small focal plaque, whereas the remaining lenses had a normal epithelial monolayer, similar to that observed in untreated eyes.

Figure 1.

Effects of adenoviral gene transfer of active TGF-β1 after 2 to 3 weeks. Histologic sections from mice injected with AdTGF-β1 or AdDL were stained with H&E (A–D) or subjected to immunostaining for α-SMA (E–H, green). Focal multilayering of LECs occurs in both wild-type (A; n = 7) and MMP-2 KO (B; n = 6) mice treated with AdTGF-β and in both cases is associated with induction of α-SMA (E and F). MMP-9 KO mice treated with AdTGF-β maintained a monolayer of LECs (C; n = 10) that did not express α-SMA (G), resembling mouse eyes injected with AdDL control vector (D and H). Note the presence of an intact lens capsule in all lenses after adenoviral injection. All sections were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (blue). The small circles in A and D are artifacts. c, cornea; i, iris; le, lens epithelium. Scale bar = 100 μm (A–H).

To confirm that the subcapsular plaques observed in the AdTGF-β1–treated eyes consisted of myofibroblasts, as previously reported in human ASC and other animal models of ASC, lens sections were prepared from postinjected eyes and subjected to immunostaining for α-SMA. In the AdTGF-β1–treated wild-type eyes, distinct expression of α-SMA was observed in a substantial proportion of cells within the plaques (Figure 1E). This was also the case for the MMP-2 KO mice injected with AdTGF-β1 (Figure 1F). In comparison, the undisrupted lens epithelial monolayer of the MMP-9 KO mice failed to stain positive for the myofibroblast cell marker, α-SMA (Figure 1G), resembling control eyes (Figure 1H).

Alteration in Markers of EMT in LECs Requires MMP-9 But Not MMP-2

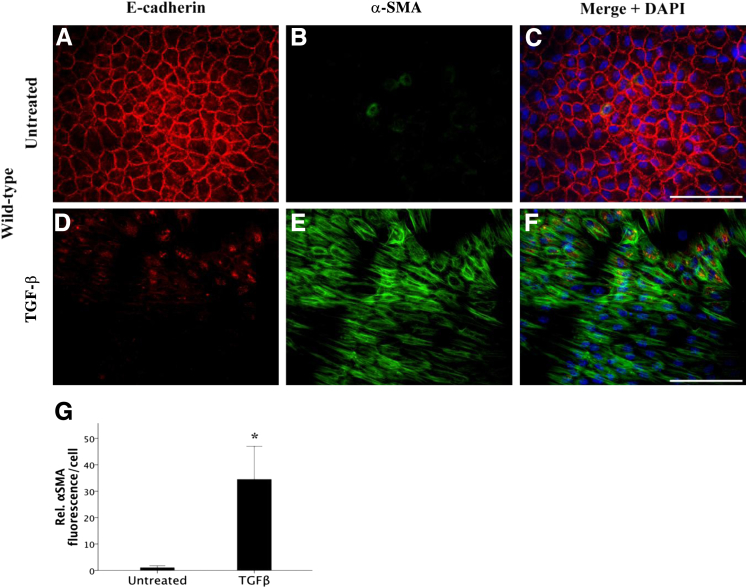

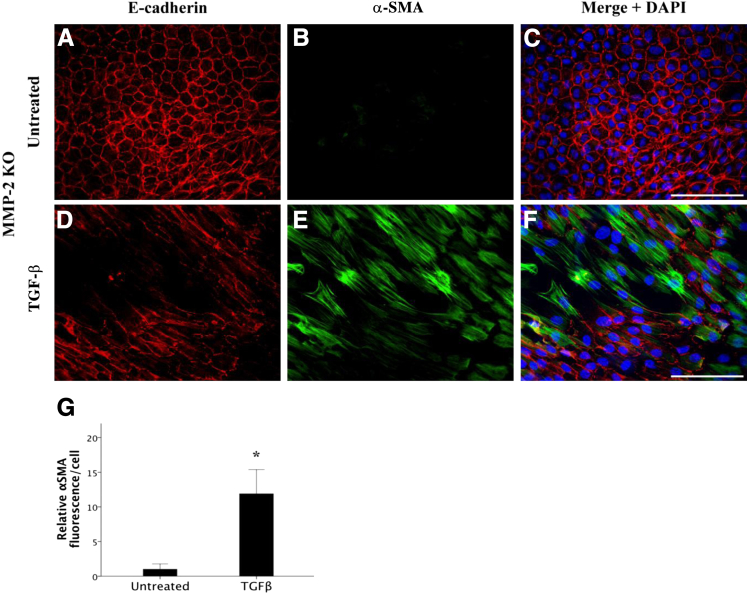

The dissolution of cell-cell contacts, notably loss of E-cadherin from epithelial cells, is a key characteristic in the transition of an epithelial cell to a mesenchymal cell. Therefore, to directly examine the effect of TGF-β on the dissolution of E-cadherin in MMP-2 and MMP-9 KO mice and their wild-type littermates, explant cultures were used. Isolating and explanting of the lens epithelium is an effective ex vivo model that is well suited for studying the mechanisms behind the transformation of these epithelial cells into a mesenchymal phenotype. Untreated wild-type explant LECs (Figure 2, A–C) exhibited the characteristic epithelial cell phenotype with clear E-cadherin staining at the cell borders and junctions (Figure 2A) accompanied by little to no α-SMA expression (Figure 2B). When wild-type explant cells were treated with 500 pg/mL TGF-β for 48 hours (Figure 2, D–F), their morphologic features drastically changed, including a distinct loss of E-cadherin expression at the cell junctions (Figure 2D) and an increase in α-SMA expression (Figure 2E), indicating that TGF-β had induced their transformation into contractile myofibroblasts. The increase in α-SMA in TGF-β–treated explants was significant (34.5 ± 12.5) relative to untreated controls (Figure 2G) (P = 0.022). In comparison, LEC explants from MMP-2 KO lenses, when left untreated, also maintained a cuboidal arrangement with intact cell junctions expressing E-cadherin and no observable α-SMA (Figure 3, A–C). Notably, in the MMP-2 KO explants, TGF-β was still able to induce a phenotypic transformation in the epithelial cell monolayer with a clear loss of E-cadherin (Figure 3D) and a significant (11.9 ± 3.5) increase in expression of filamentous α-SMA (Figure 3, E and G) (P = 0.003) comparable to treated wild-type LEC explants. These data substantiate the results from the AdTGF-β injection experiments, suggesting that MMP-2 is not required for TGF-β–mediated EMT.

Figure 2.

Effects of TGF-β on E-cadherin localization and α-SMA levels in wild-type mouse LEC explants. Confluent LEC explants when left untreated (A–C; n = 9) maintain a tightly packed, cuboidal, cobblestone-like appearance in a monolayer with E-cadherin expressed at cellular junctions (A) and negligible α-SMA expression (B, green). Mouse LECs treated with 500 pg/mL of TGF-β for 48 hours (D–F; n = 10) exhibit a distinct loss of E-cadherin (D) and marked expression of α-SMA (E). G: TGF-β leads to a significant induction in α-SMA compared with untreated wild-type lens explants. All explants were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (C and F, blue). Scale bar = 100 μm (A–F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effects of TGF-β treatment on E-cadherin localization and α-SMA levels in MMP-2 KO mouse lens epithelial explants. MMP-2 KO explanted LECs, when left untreated (A–C; n = 10), maintained a cuboidal arrangement with E-cadherin staining present at intact cellular junctions (A) and negligible α-SMA expression (B, green) similar to wild-type LECs. In the absence of MMP-2, 500 pg/mL of TGF-β treatment for 48 hours (D–F; n = 7) induced a phenotypic transformation with a distinct loss of E-cadherin (D) and marked expression of α-SMA (E), similar to treated wild-type LECs. G: TGF-β leads to a significant induction in α-SMA compared with untreated MMP-2 KO lens explants. All explants were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (C and F, blue). Scale bar = 100 μm (A–F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05.

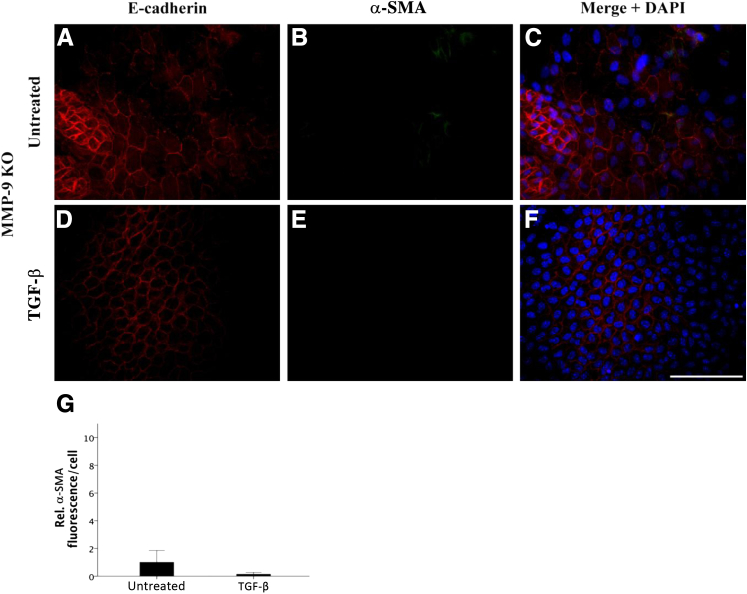

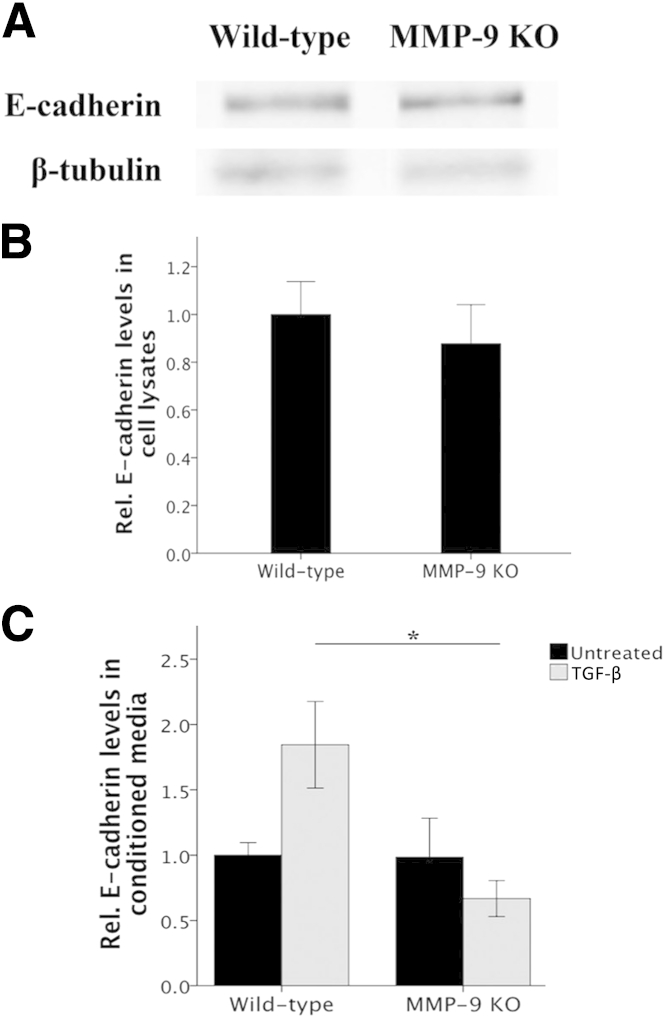

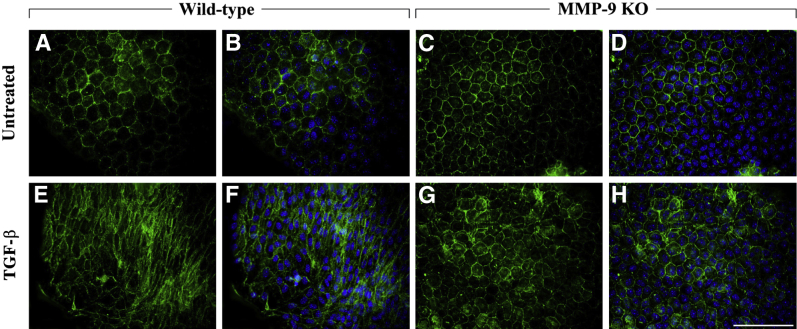

MMP-9 KO LEC explants, when left untreated, do not resemble wild-type untreated explants (Figure 4, A–C). In the absence of MMP-9 and without stimulation with TGF-β, E-cadherin staining of cells was irregular and absent in some cells (Figure 4A). This staining pattern remained the same with TGF-β treatment (Figure 4D). In terms of myofibroblast marker acquisition, untreated MMP-9 KO LECs expressed no observable α-SMA (Figure 4B). Importantly, MMP-9 KO LECs treated with TGF-β (Figure 4, D–F) did not acquire a characteristic spindle-like mesenchymal phenotype, and α-SMA expression (Figure 4E) did not significantly differ from MMP-9 KO untreated control cells (Figure 4G). We also performed Western blot analyses to determine the overall level of E-cadherin protein in MMP-9 KO LEC lysates compared with that of wild-type littermates (Figure 5A). These experiments demonstrated that despite the altered staining of E-cadherin in the MMP-9 KO explants, the levels of E-cadherin protein were not significantly different from those of wild-type mice (Figure 5B). Because our earlier study using ex vivo rat lenses revealed the appearance of a 72-kDa E-cadherin fragment in the conditioned media of lenses treated with TGF-β that was not detected in the media from untreated lenses,23 we also assayed the conditioned media of the explants from wild-type and MMP-9 KO mice using an ELISA specific for E-cadherin (Figure 5C). These experiments revealed that unlike TGF-β–treated wild-type explants that exhibited induced E-cadherin levels in the media compared with untreated controls (P = 0.074), the TGF-β–treated MMP-9 KO explants did not. In fact, the levels of E-cadherin in the TGF-β–treated MMP-9 KO media were lower than all untreated explants and significantly lower than that of wild-type TGF-β–treated explants (P = 0.019).

Figure 4.

Effects of TGF-β treatment on E-cadherin localization and α-SMA levels in MMP-9 KO mouse lens epithelial explants. MMP-9 KO LEC explants when left untreated (A–C; n = 9) exhibited irregular E-cadherin staining (A) with negligible α-SMA expression (B, green). LECs treated with 500 pg/mL of TGF-β for 48 hours in the absence of MMP-9 (D–F; n = 5) maintained a similar E-cadherin profile as the untreated controls (D) and, in contrast to TGF-β–treated wild-type and MMP-2 KO explants, did not express α-SMA (E). G: TGF-β did not significantly induce α-SMA expression when compared with untreated MMP-9 KO lens explants. All explants were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (C and F, blue). Scale bar = 100 μm (A–F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 5.

E-cadherin protein levels in LEC explant lysates and conditioned media. A: Representative Western blot reveals E-cadherin protein (120 kDa) in MMP-9 KO LEC explant lysates compared with their wild-type littermates. B: Densitometric analysis of Western blot in LEC explant lysates indicate no significant difference in total E-cadherin protein between MMP-9 KO (n = 8) and wild-type (n = 5) LEC explants. Data were normalized with β-tubulin control and are expressed as means ± SEM. C: ELISA measuring E-cadherin in conditioned media of untreated and 500 pg/mL of TGF-β–treated (for 48 hours) wild-type and MMP-9 KO LEC explants. In the media, TGF-β treatment leads to an increase in E-cadherin protein in wild-type explants when compared with untreated wild-type controls. Levels of E-cadherin in the media of MMP-9 KO explants after TGF-β treatment are significantly different from wild-type TGF-β–treated levels (P = 0.019) and comparable to all untreated explant levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 to 6). ∗P < 0.05.

Finally, to further investigate the resistance of the MMP-9 KO LEC explants to TGF-β–induced EMT, we used another known marker of EMT, β-catenin. β-catenin is important in linking E-cadherin to the cell cytoskeleton, and its loss from the cell margins often precedes EMT in many systems. Thus, activation of β-catenin, in which β-catenin localization changes from a marginal localization pattern to a more cytosolic and/or nuclear expression has been found to occur in LEC explant cells after TGF-β treatment.39 Our experiments found that wild-type explants treated with TGF-β exhibited predominantly cytosolic expression of β-catenin (Figure 6, E and F) compared with untreated controls (Figure 6, A and B), which exhibit a more marginal staining that reflects the cobblestone packing of the cells. Importantly, the MMP-9 KO explants treated with TGF-β (Figure 6, G and H) resembled untreated controls with marginal cell border staining (Figure 6, C and D). These findings further confirm the resistance of the MMP-9 KO explants to TGF-β–induced EMT.

Figure 6.

Effects of TGF-β treatment on β-catenin localization in MMP-9 KO mouse lens epithelial explants. In untreated wild-type (A and B) and MMP-9 KO (C and D) explants, β-catenin is predominantly localized at the cellular margins in a cobblestone arrangement. With 500 pg/mL of TGF-β treatment for 48 hours, wild-type LECs exhibit primarily cytosolic expression of β-catenin (E and F), in contrast to TGF-β–treated MMP-9 KO explants, which resembled controls with marginal staining of β-catenin at cell borders (G and H). All explants were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 100 μm.

ASC Formation Is Suppressed When TGF-β Transgenic Mice Are Bred onto the MMP-9 KO Background

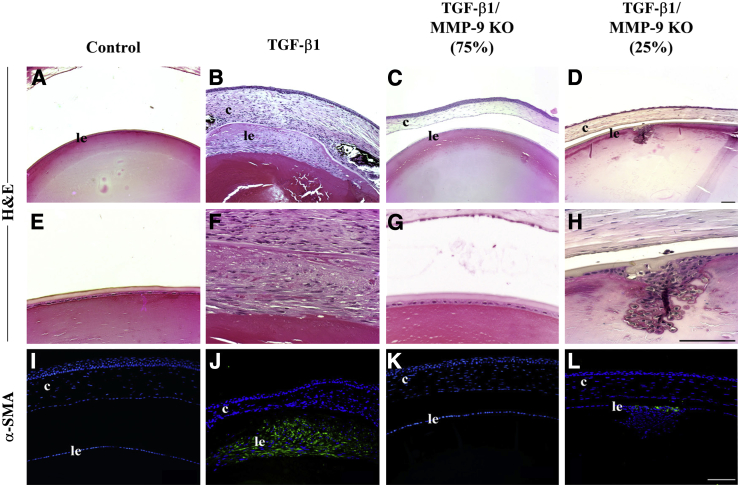

To corroborate the AdTGF-β findings, we also assessed the involvement of MMP-9 in a TGF-β1 lens-specific transgenic model. This model involves the overexpression of self-activating TGF-β1 driven by a lens-specific αA-crystallin promoter.32 TGF-β1 transgenic mice develop one centrally localized fibrotic ASC beginning 3 weeks after birth. These mice were crossed onto the MMP-9 null background to obtain TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice. All transgenic mice that were on the MMP-9 wild-type background (TGF-β1+/MMP-9+/+) developed focal multilayered opacities (Figure 7, B and F). Interestingly, 75% of lenses derived from TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice were devoid of multilayered plaques (Figure 7, C and G) and exhibited a phenotype similar to lenses without the TGF-β1 transgene (Figure 7, A and E), exhibiting the characteristic monolayer of lens epithelial cells. The remaining 25% of TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice developed focal multilayered plaques (Figure 7, D and H). All lenses were subjected to IHC for α-SMA to determine whether they contained myofibroblasts, indicative of EMT. All of the lenses of TGF-β1/MMP-9 wild-type mice exhibited α-SMA reactivity in areas where focal opacities had developed (Figure 7J). Similarly, plaques that developed in the 25% of the TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO lenses also expressed α-SMA (Figure 7L). Control lenses (Figure 7I) and the 75% of the TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO lenses that did not exhibit ASC formation (Figure 7K) were also devoid of α-SMA.

Figure 7.

Lens epithelium of TGF-β1 transgenic and TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice at 1 to 3 months of age. Histologic sections were stained with H&E or subjected to immunostaining for α-SMA (I–L, green). Unlike control lenses (A and E; n = 12), TGF-β1 transgenics at this time point exhibit reorganization of cells and plaque formation exuding into the anterior chamber (B and F; n = 10), with immunoreactivity of α-SMA confirming the presence of subcapsular plaques (J compared with control, I). In 75% of TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice, a protection from plaque formation was observed (C and G) with no immunoreactivity for α-SMA (K; n = 14), whereas 25% of TGF-β1/MMP-9 KO mice did develop subcapsular plaques (D and H) with α-SMA reactivity (L; n = 5). All sections were mounted in medium with DAPI to co-localize the nuclei (blue). c, cornea; le, lens epithelium. Scale bar = 100 μm. Original magnification: ×20 (A–D); ×40 (E–H).

Discussion

Proteases, such as the MMPs, are known to play a role in lens development and cataract formation. However, the functional requirement of MMPs in mediating cataractogenesis has only recently been investigated, and much attention has been focused on the fibrotic cataract phenotypes ASC and PCO. Clinically, ASC and PCO have been associated with elevated levels of active TGF-β, and experimental models for both of these cataracts have been developed using active TGF-β as a stimulus.10,16 MMPs, and in particular MMP-2 and MMP-9, have been found to proteolytically cleave latent TGF-β.40,41 Thus, it is feasible that MMPs act upstream in initiating TGF-β activation during early wound healing events associated with ASC and PCO. However, it has also been clearly indicated that MMPs play a role(s) in regulating the cellular changes that occur subsequent to treatment with active TGF-β, including LEC migration, capsular contraction, and the EMT of LECs.16 For example, previous studies, using the excised rat lens model, have found that the inhibition of the matrix-degrading enzymes, MMP-2 and MMP-9, results in suppression of (active) TGF-β–mediated EMT and subsequent ASC formation.23 The current study has extended this work and addressed the individual requirement(s) of these two MMPs in ASC formation by examining whether TGF-β–mediated ASC would form on a MMP-2 or MMP-9 KO mouse background. Our results indicated that nearly all the MMP-9 KO mice failed to elicit ASC plaque formation after adenoviral gene transfer of active TGF-β1 to the anterior chamber, in contrast to the MMP-2 KO mice, which exhibited ASC formation in all cases. The resistance to ASC formation in the MMP-9 KO mice was also accompanied by a lack of expression of the myofibroblast marker α-SMA. To further corroborate these findings, the MMP-9 KO mice were bred onto a transgenic mouse background with lens-specific overexpression of self-activating TGF-β1. These findings further indicated a resistance to ASC formation in the absence of MMP-9 because 75% of the TGF-β1 transgenic mice on the MMP-9 KO background did not develop cataracts. Together these findings indicate that, of the two gelatinases investigated, MMP-9 expression is most critical in mediating TGF-β–induced ASC formation.

Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression have been detected in the normal rat and mouse lens.23,42,43 However, a number of studies have reported that although MMP-9 is constitutively expressed in the lens, MMP-2 expression appears after treatment with growth factors or during cataract formation.44,45 Our studies using the ex vivo rat lens indicated that, although MMP-9 secreted protein could be detected in untreated lenses, MMP-2 levels could not and were only apparent after treatment with TGF-β.23 Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ASC plaque cells from rat lenses further revealed an early induction of MMP-9 mRNA after 2 days of TGF-β treatment, whereas MMP-2 was found to be up-regulated at the later 4-day time point.22 A similar, coordinated expression pattern of MMP-9 and MMP-2 has also been described in other model systems of fibrosis. For example, on ligation of the carotid artery and subsequent remodeling, MMP-9 expression was found to be significantly elevated above controls, and induction in MMP-2 expression commenced after the peak of MMP-9 expression.27 Additional evidence suggests that MMP-9 may act upstream of MMP-2 in EMT. Stimulation of human LECs with human recombinant MMP-9 was found to result in induction in expression of MMP-2, and this was correlated with increased expression of the EMT marker α-SMA.22 Although there is no evidence that MMP-9 directly regulates MMP-2 expression, there are indirect mechanisms by which MMP-9 may influence MMP-2. For example, MMP-14, which is known to induce MMP-2 in other systems,46 was found to be up-regulated in rat lenses 4 days after TGF-β treatment and 2 days after MMP-9 induction.22 Thus, induction in MMP-9 expression was found to precede MMP-14 and, as such, may act as an intermediate for regulating MMP-2 expression.

The two gelatinases, MMP-2 and MMP-9, are known to have similar substrate specificities for matrix proteins47,48 and have been found to work in concert in disease. For example, in an experimental laser model of choroidal neovascularization, deficiency in both MMP-2 and MMP-9 resulted in increased incidence and severity of the disease compared with absence in only one of the two MMPs.28 MMP-2 and MMP-9 have, however, been found to possess different roles in the cleaving of nonmatrix substrates. MMP-2 can cleave sites of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 3, but MMP-9 cannot.49,50 In addition, through its proteolytic activity, MMP-2 has been found to release fibroblast growth factor 2 from the lens capsule, contributing to lens epithelial cell survival.51 Our earlier data suggested that MMP-2 and/or MMP-9 may facilitate EMT of LECs by acting on the nonmatrix substrate E-cadherin. E-cadherin has been recognized as a critical factor in maintaining the epithelial cell state, and its disruption has been associated with the initial stages of transition to a mesenchymal phenotype.52,53 Proteolytic cleavage of the N-terminal extracellular domain of E-cadherin by MMPs, referred to as E-cadherin shedding, results in the formation of an E-cadherin extracellular domain fragment with reported sizes ranging from 50 to 84 kDa, compared with the intact 120-kDa protein.54 Indeed, in a previous study we detected a shed 72-kDa E-cadherin fragment in the conditioned media of lenses treated with TGF-β2 that was not detected in the media from untreated lenses.23 Importantly, the appearance of the E-cadherin fragment in the TGF-β–treated rat lenses was attenuated by co-treatment with an MMP-2/MMP-9–specific inhibitor, implicating these two MMPs in the shedding process. In the current study, we used lens epithelial explants from MMP-2 and MMP-9 KO mice to further examine E-cadherin. Explants from both wild-type and MMP-2 KO mice, after treatment with TGF-β, exhibited cell-cell detachment with a distinct loss in E-cadherin together with predominantly cytosolic β-catenin localization, an elongation in cell shape, and increased expression of α-SMA. Interestingly, the MMP-9 KO explants, without TGF-β treatment, exhibited irregular localization of E-cadherin compared with their wild-type explants, and in some cells it appeared reduced. Despite this staining pattern, overall E-cadherin protein levels in the lens explant lysates from MMP-9 KO mice versus wild-type mice were found to be the same. In addition, the levels of E-cadherin protein shed into the media from the explants after TGF-β treatment were found to be significantly lower in the MMP-9 KO explants compared with wild-type explants. Thus, the TGF-β–induced disruption or change in E-cadherin that is observed in the wild-type (and MMP-2 KO) explant cells does not occur in the MMP-9 KO explants, and correspondingly the MMP-9 KO explants did not exhibit TGF-β–induced EMT-like changes, including β-catenin localization and α-SMA expression. It is not known why the E-cadherin staining pattern would be altered in the MMP-9 KO LECs; however, a recent report found that astrocytes from MMP-9 KO mice exhibited an altered actin cytoskeleton and perturbed cell migration.55 The actin cytoskeleton is known to regulate E-cadherin localization and stability56; thus, it is possible that MMP-9 KO LECs have an altered cytoskeletal arrangement. Because our laboratory and others have found that actin-mediated signaling is involved in the EMT of LECs,38,57 it will be important to further investigate how the loss of MMP-9 may have an effect.

Our findings also revealed that compared with the adenoviral delivery model, the TGF-β transgenic model had an increase in incidence in ASC formation with mice on the MMP-9 KO background (25% exhibited cataracts versus the 9% in the adenoviral delivery model). One possible explanation for these findings may be related to the delivery mode of active TGF-β. In the transgenic model, the TGF-β1 transgene is continuously producing self-activating TGF-β1 protein beginning at embryonic day 15 and continuing for the entire life span of the mouse, whereas adenoviral delivery of TGF-β1 to the anterior chamber and lens is transient. Thus, the transgenic approach may deliver larger and long-term levels of active TGF-β than that of the adenoviral method. Indeed, different transgenic promoters, with different strengths, have been found to result in variability in the severity of anterior chamber and lens defects in mice.58,59 Thus, some variation between models is apparent and likely dependent on the levels of active TGF-β and length of exposure. Nonetheless, in both the TGF-β transgenic and the AdTGF-β model, MMP-9 KO mice exhibited a resistance to ASC formation, whereas MMP-2 KO mice did not. A small number of the MMP-9 KO mice developed cataracts, indicating that alternate MMP-9–independent mechanisms can mediate TGF-β–induced ASC formation. This is not surprising given the complex nature of TGF-β signaling and numerous downstream pathways, as well as the potential involvement of other MMP family members that have also been implicated in regulating EMT.18 Why some mice of the same background developed ASC and others did not is unknown. However, one possibility is that the levels of active TGF-β among the mice tested in both in vivo models may have varied, leading to the stimulation of alternate signaling pathways.

A number of studies have implicated MMPs, in particular MMP-2 and MMP-9, in the EMT of LECs and in mediating ASC formation. However, their individual roles had yet to be characterized. This study has found that MMP-9 but not MMP-2 expression is necessary for TGF-β–mediated lens EMT and ASC formation. The mechanism(s) by which MMP-9 deficiency results in resistance to TGF-β–induced EMT in the lens and how this may involve actin cytoskeleton signaling will be important for future investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jack Gauldie (McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada) for providing the adenoviral TGF-β and delete vectors, Paul Overbeek (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) for providing the transgenic TGF-β1 mice, and Dr. Farrah Kheradmand (Baylor College of Medicine) for MMP-2 KO mice.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH grant R01-017146-06 (J.W.M.) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council 20/20 Network (H.S.).

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. Blindness: vision 2020: The Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness. Fact sheet 213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. Visual Impairment and Blindness. Fact sheet 282. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascolini D., Mariotti S.P. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:614–618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen P.J. Cataract surgery practice and endophthalmitis prevention by Australian and New Zealand ophthalmologists–comment. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35:391. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West S.K. Looking forward to 20/20: a focus on the epidemiology of eye diseases. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:64–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullimore M.A., Bailey I.L. Considerations in the subjective assessment of cataract. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:880–885. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kappelhof J.P., Vrensen G.F. The pathology of after-cataract: a minireview. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1992:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1992.tb02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaumberg D.A., Dana M.R., Christen W.G., Glynn R.J. A systematic overview of the incidence of posterior capsule opacification. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)97023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wormstone I.M., Tamiya S., Anderson I., Duncan G. TGF-β2-induced matrix modification and cell transdifferentiation in the human lens capsular bag. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2301–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wormstone I.M. Posterior capsule opacification: a cell biological perspective. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:337–347. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novotny G.E. Formation of cytoplasm-containing vesicles from double-walled coated invaginations containing oligodendrocytic cytoplasm at the axon-myelin sheath interface in adult mammalian central nervous system. Acta Anat (Basel) 1984;119:106–112. doi: 10.1159/000145869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay E.D. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat (Basel) 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Font R., SA B. A light and electron microscopic study of anterior subcapsular cataracts. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;78:972–984. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander C.M., Werb Z. Proteinases and extracellular matrix remodeling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989;1:974–982. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fini M.E., Cook J.R., Mohan R., Brinkerhoff C.E. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. In: Parks W.C., Mecham R.P., editors. Matrix Metalloproteinases. Academic Press; New York: 1998. pp. 299–356. [Google Scholar]

- 16.West-Mays J.A., Pino G. Matrix metalloproteinases as mediators of primary and secondary cataracts. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2:931–938. doi: 10.1586/17469899.2.6.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seomun Y., Kim J., Lee E.H., Joo C.K. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 mediates phenotypic transformation of lens epithelial cells. Biochem J. 2001;358:41–48. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternlicht M.D., Lochter A., Sympson C.J., Huey B., Rougier J.P., Gray J.W., Pinkel D., Bissell M.J., Werb Z. The stromal proteinase MMP3/stromelysin-1 promotes mammary carcinogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alapure B.V., Praveen M.R., Gajjar D.U., Vasavada A.R., Parmar T.J., Arora A.I. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 activities in the human lens epithelial cells and serum of steroid induced posterior subcapsular cataracts. Mol Vis. 2012;18:64–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldred J.A., Hodgkinson L.M., Dawes L.J., Reddan J.R., Edwards D.R., Wormstone I.M. MMP2 activity is critical for TGFβ2-induced matrix contraction–implications for fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4085–4098. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazra S., Guha R., Jongkey G., Palui H., Mishra A., Vemuganti G.K., Basak S.K., Mandal T.K., Konar A. Modulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity by EDTA prevents posterior capsular opacification. Mol Vis. 2012;18:1701–1711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathu Z., Dwivedi D.J., Reddan J.R., Sheardown H., Margetts P.J., West-Mays J.A. Temporal changes in MMP mRNA expression in the lens epithelium during anterior subcapsular cataract formation. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwivedi D.J., Pino G., Banh A., Nathu Z., Howchin D., Margetts P., Sivak J.G., West-Mays J.A. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors suppress transforming growth factor-β-induced subcapsular cataract formation. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:69–79. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.041089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cousins S.W., McCabe M.M., Danielpour D., Streilein J.W. Identification of transforming growth factor-β as an immunosuppressive factor in aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2201–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hales A.M., Chamberlain C.G., McAvoy J.W. Cataract induction in lenses cultured with transforming growth factor-β. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1709–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hales A.M., Chamberlain C.G., Dreher B., McAvoy J.W. Intravitreal injection of TGFβ induces cataract in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:3231–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godin D., Ivan E., Johnson C., Magid R., Galis Z.S. Remodeling of carotid artery is associated with increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases in mouse blood flow cessation model. Circulation. 2000;102:2861–2866. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert V., Wielockx B., Munaut C., Galopin C., Jost M., Itoh T., Werb Z., Baker A., Libert C., Krell H.W., Foidart J.M., Noel A., Rakic J.M. MMP-2 and MMP-9 synergize in promoting choroidal neovascularization. FASEB J. 2003;17:2290–2292. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0113fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corry D.B., Kiss A., Song L.Z., Song L., Xu J., Lee S.H., Werb Z., Kheradmand F. Overlapping and independent contributions of MMP2 and MMP9 to lung allergic inflammatory cell egression through decreased CC chemokines. FASEB J. 2004;18:995–997. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1412fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu T.H., Shipley J.M., Bergers G., Berger J.E., Helms J.A., Hanahan D., Shapiro S.D., Senior R.M., Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh T., Ikeda T., Gomi H., Nakao S., Suzuki T., Itohara S. Unaltered secretion of beta-amyloid precursor protein in gelatinase A (matrix metalloproteinase 2)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22389–22392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivasan Y., Lovicu F.J., Overbeek P.A. Lens-specific expression of transforming growth factor β1 in transgenic mice causes anterior subcapsular cataracts. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:625–634. doi: 10.1172/JCI1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margetts P.J. Transient overexpression of TGF-β1 induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in the rodent peritoneum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:425–436. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunner A.M., Marquardt H., Malacko A.R., Lioubin M.N., Purchio A.F. Site-directed mutagenesis of cysteine residues in the pro region of the transforming growth factor β1 precursor: expression and characterization of mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13660–13664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sime P.J., Xing Z., Graham F.L., Csaky K.G., Gauldie J. Adenovector-mediated gene transfer of active transforming growth factor-β1 induces prolonged severe fibrosis in rat lung. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:768–776. doi: 10.1172/JCI119590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Margetts P.J., Kolb M., Galt T., Hoff C.M., Shockley T.R., Gauldie J. Gene transfer of transforming growth factor-β1 to the rat peritoneum: effects on membrane function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2029–2039. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson J.V., Nathu Z., Najjar A., Dwivedi D., Gauldie J., West-Mays J.A. Adenoviral gene transfer of bioactive TGFβ1 to the rodent eye as a novel model for anterior subcapsular cataract. Mol Vis. 2007;13:457–469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta M., Korol A., West-Mays J.A. Nuclear translocation of myocardin-related transcription factor-A during transforming growth factor beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition of lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2013;19:1017–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stump R.J., Lovicu F.J., Ang S.L., Pandey S.K., McAvoy J.W. Lithium stabilizes the polarized lens epithelial phenotype and inhibits proliferation, migration, and epithelial mesenchymal transition. J Pathol. 2006;210:249–257. doi: 10.1002/path.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dallas S.L., Rosser J.L., Mundy G.R., Bonewald L.F. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts: a cellular mechanism for release of TGF-beta from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21352–21360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q., Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-β and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Descamps F.J., Martens E., Proost P., Starckx S., Van den Steen P.E., Van Damme J., Opdenakker G. Gelatinase B/matrix metalloproteinase-9 provokes cataract by cleaving lens βB1 crystallin. FASEB J. 2005;19:29–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1837com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.John M., Jaworski C., Chen Z., Subramanian S., Ma W., Sun F., Li D., Spector A., Carper D. Matrix metalloproteinases are down-regulated in rat lenses exposed to oxidative stress. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohan R., Chintala S.K., Jung J.C., Villar W.V., McCabe F., Russo L.A., Lee Y., McCarthy B.E., Wollenberg K.R., Jester J.V., Wang M., Welgus H.G., Shipley J.M., Senior R.M., Fini M.E. Matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) coordinates and effects epithelial regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2065–2072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reponen P., Sahlberg C., Huhtala P., Hurskainen T., Thesleff I., Tryggvason K. Molecular cloning of murine 72-kDa type IV collagenase and its expression during mouse development. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7856–7862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato H., Takino T. Coordinate action of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MT1-MMP) and MMP-2 enhances pericellular proteolysis and invasion. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:843–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matrisian L.M. The matrix-degrading metalloproteinases. Bioessays. 1992;14:455–463. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woessner J.F., Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991;5:2145–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levi E., Fridman R., Miao H.Q., Ma Y.S., Yayon A., Vlodavsky I. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 releases active soluble ectodomain of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7069–7074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McQuibban G.A., Gong J.H., Tam E.M., McCulloch C.A., Clark-Lewis I., Overall C.M. Inflammation dampened by gelatinase A cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science. 2000;289:1202–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quinlan M., Wormstone I.M., Duncan G., Davies P.D. Phacoemulsification versus extracapsular cataract extraction: a comparative study of cell survival and growth on the human capsular bag in vitro. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:907–910. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.10.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Imhof B.A., Vollmers H.P., Goodman S.L., Birchmeier W. Cell-cell interaction and polarity of epithelial cells: specific perturbation using a monoclonal antibody. Cell. 1983;35:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thiery J.P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinhusen U., Weiske J., Badock V., Tauber R., Bommert K., Huber O. Cleavage and shedding of E-cadherin after induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4972–4980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsu J.Y., Bourguignon L.Y., Adams C.M., Peyrollier K., Zhang H., Fandel T., Cun C.L., Werb Z., Noble-Haeusslein L.J. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 facilitates glial scar formation in the injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13467–13477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2287-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cavey M., Rauzi M., Lenne P.F., Lecuit T. A two-tiered mechanism for stabilization and immobilization of E-cadherin. Nature. 2008;453:751–756. doi: 10.1038/nature06953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho H.J., Yoo J. Rho activation is required for transforming growth factor- β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lens epithelial cells. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banh A. Lens-specific expression of TGFβ induces anterior subcapsular cataract formation in the absence of Smad3. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3450–3460. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flugel-Koch C., Ohlmann A., Piatigorsky J., Tamm E.R. Disruption of anterior segment development by TGF-β1 overexpression in the eyes of transgenic mice. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:111–125. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]