Abstract

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) including lymphoid tissue-inducer (LTi) cells, IL-22-producing NKp46+ innate cells and IL-13-producing nuocytes play important roles in regulating intestinal microbiota, defence against pathogens and formation of lymphoid tissue1-4. Their development is dependent on Id2 and Rorγt or Rorα5-7. Lineage tracing experiments have shown that the common lymphoid precursor gives rise to nuocytes, LTi cells and NKp46+ ILCs6,8,9, but these studies have not deciphered the discrete steps and transcription factors that specify ILC subset development, activation and maintenance. Whether NKp46+ ILCs arise directly from LTi cells, or rather represent a separate lineage that diverges earlier in development, remains controversial10-12. We investigated the requirement for the transcriptional master regulator T-bet (encoded by Tbx21) which is critical for the development of both T cells and NK cells13,14, in driving differentiation of ILC populations. Here we report that T-bet played an essential role for the development of NKp46+ ILCs, but was dispensable for LTi cells or nuocytes. Tbx21+/+ LTi cells adopted an NKp46+ phenotype in vitro and in vivo but not in the absence of Tbx21. Decrease of T-bet expression coordinately reduced Notch1 and Notch2 and we show Notch signaling is necessary for the transition of LTi cells into NKp46+ ILCs. In addition, Tbx21−/− mice have an accumulation in CD4− LTi cells and differentiation into NKp46+ ILCs came solely from this population. Our results pinpoint T-bet as the critical regulator of NKp46+ ILC differentiation by regulation of Notch2 signaling. NKp46+ cells are an important element of the protective intestinal mucosal cellular arsenal, and here, we uncover the distinct molecular pathways that guide the development of NKp46+ ILCs.

Keywords: Lymphoid tissue inducer cells, innate lymphoid cells, nuocytes, NKp46, GFP reporter mouse

An emerging theme linking the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system is the striking conservation of genetic regulatory programs driving cell differentiation and fate decisions15. ILC populations, namely LTi cells (Lin−NKp46−NK1.1−c-Kithigh), NKp46+ ILCs (Lin−NKp46+NK1.1low/−) and NK cells (Lin−NKp46+NK1.1+) require the transcription factor Id2 for their development and Rorγt is also essential for LTi cells and NKp46+ ILCs5,7. The transcription factor T-bet (encoded by Tbx21) has been implicated in the development of both CD8+ T cells and NK cells13,16,17, but has not been investigated in the lineage specification of these newly defined innate lymphocyte populations. To determine whether T-bet plays a role in ILC development, we took advantage of the Rorc(γt)gfp/+7 reporter mice and surface receptor staining to track each of these populations (Supplementary Fig. 1). We investigated ILC populations in naive Rorc(γt)gfp/gfp, Rorc(γt)gfp/+, Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice (Fig. 1). Strikingly, T-bet deficient mice completely lacked NKp46+ ILCs, while LTi cells could readily be detected (Fig. 1a). Immunohistochemistry on frozen sections confirmed that NKp46+Rorγt-GFP+ cells could not be detected in the tissues of the small intestine in Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice despite the presence of cryptopatches (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2), an important site of localization of NKp46+ ILCs in normal gut tissues18. Enumeration of the prevalence of ILC populations in lymphoid and gastrointestinal tissues confirmed a lack of NKp46+ ILCs and showed that NK cells were reduced in liver and spleen in Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice, consistent with previous reports13,19 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1. NKp46+ ILCs fail to form in the absence of the transcription factor T-bet.

Innate lymphocytes isolated from the small intestinal lamina propria were analysed for in T-bet deficient mice and for T-bet expression. a, Lamina propria cells were isolated from the small intestine (upper panels) and colon (lower panels) of Rorc(γt)gfp/+, Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/−, and Rorc(γt)gfp/gfp mice. It should be noted that in the colon, only a single population of NKp46+Rorγt+ cells exists in Tbx21+/+ mice and this population was also lacking in Tbx21−/− mice. Numbers indicate the percentage of live CD45+lin− (CD11c−Gr-1−CD19−CD3ε−CD45+) cells for gated type of cell. Plots are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with three to four mice of each genotype per experiment. b, Small intestine sections from naïve Rorc(γt)gfp/+(upper panels) and Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− (lower panels) mice showing cryptopatches stained with anti-NKp46 (light blue), anti-CD3ε or anti-B220 (red), anti-CD326 (EpcCAM, white) to delineate gut epithelial cells, and endogenous expression of Rorγt-GFP (green). Inset shows NKp46+ staining in Rorγt+ cells. Scale bar, 50μM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (n=6 per genotype). c, Innate lymphocytes from small intestinal lamina propria expressing different levels of Rorγt-GFP (left panel, gating strategy shown in dot plot) were stained for surface lineage markers, then fixed and permeabilized prior to staining to detect intracellular T-bet (right panels, histograms). Grey histrogram shows T-bet specific stain, dotted line indicates control stain. c, Gating stategy and analyses of individual innate lymphocyte subsets purified by flow cytometry. Tbx21 mRNA was analysed by quantitative PCR and show mean ± s.e.m. normalised to Hprt of triplicate samples showing one representative experiment of three. Dot plots are gated on lin−CD45+ cells. d, Intrinsic T-bet expression is required for NKp46+ ILC development. Mixed foetal liver chimeric mice were generated by transplanting Ly5.1/5.2+ Rorc(γt)gfp/+ and Ly5.2+ Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− cells into lethally irradiated Ly5.1 mice. After 8 weeks, innate lymphocytes were isolated from the lamina propria of the small intestine and colon and the capacity for Tbx21+/+ (Ly5.1+/5.2+) or Tbx21−/− (Ly5.2+) foetal liver cells to reconstitute innate lymphocytes was evaluated. Numbers indicate the frequency of each ILC population within the lin−CD45+ live SYTOX Blue− cell gate which were then examined for expression of α4β7, c-Kit, IL-7R and RORγt-GFP. Data show representative profiles from two independent experiments (n=8) with similar results. As gated cells in (c) are fixed, some change in Rorγt-GFP resolution is observed when compared to unfixed cells shown in (a, d).

Analysis of T-bet expression in innate lymphocyte populations by intracellular staining and mRNA levels revealed high expression of T-bet in both NKp46+ ILCs and NK (lin−Rorγt−NKp46+NK1.1+) cells isolated from the intestine, while T-bet was not expressed in LTi cells (Fig. 1c). The related T-box factor Eomes, that performs similar functions to T-bet in CD8+ T cells and NK cells, was not expressed in NKp46+ ILCs or LTi cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Thus, T-bet appears to play a crucial role in the development of NKp46+ ILCs. Similar to T-bet, Blimp1 (encoded by Prdm1) was strongly differentially expressed between LTi and NKp46+ ILC populations (Supplementary Fig. 3b). However, mice homozygously deficient for Blimp1 (Blimp1gfp/gfp) did not show any apparent defect in the development of ILC subsets (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Thus, Blimp1 is dispensable for ILC differentiation while T-bet is essential.

T-bet is a critical regulator of many aspects of lymphocyte differentiation and may affect the expression of key cell surface receptors such as NKp46 used to identify ILCs. As Tbx21−/− NK cells retained normal expression of NKp46, failure to detect NKp46+ ILCs in Tbx21−/− mice was unlikely to be due to dysregulation of the NKp46 receptor itself. To further discount an effect of Tbx21 on NKp46 expression in ILCs, we examined the expression of Blimp1. Blimp1gfp/+Tbx21−/− LTi cells did not express altered levels of Blimp1-GFP or other markers that would be characteristic of a contaminating NKp46+ ILC population (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). Thus, NKp46+ ILCs require T-bet for their development and failure to detect this population is not attributable to loss of receptor expression.

To uncover where the defect in generation of NKp46+ ILCs arises, we investigated ILC precursor cells found in foetal liver20. Analysis of E14.5 embryonic liver cells showed no significant differences between the Rorc(γt)gfp/+ and Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− strains (Supplementary Fig. 5). Additionally, in adult mice the size and number of Peyer’s patch did not differ between the two strains (Supplementary Fig. 6; data not shown) and tissues showed normal architecture with no evidence of inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 6) indicating that the loss of Tbx21 did not obviously disrupt secondary lymphoid tissue formation. As no adverse affects were noted in gross histology, we investigated the importance of NKp46+ ILCs following Citrobacter rodentium infection. In this model, IL-22 production has a crucial role in the protection against C. rodentium dissemination, and NKp46+ ILCs are a key producer of this cytokine21,22.. Eight days following infection, Tbx21−/− mice exhibited shorter colon lengths and increased bacterial dissemination into the liver and spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7a. The increased susceptibility to C. rodentium infection correlated with the loss of NKp46+ ILCs and fewer Rorc(γt)+ IL-22 producing ILCs (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

Loss of T-bet within the haematopoietic compartment results in dysfunction of various immune cells in the intestine. For example, T-bet deficient dendritic cells produce markedly elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α that could influence the developing ILCs23. Therefore, we investigated whether the absence of T-bet affected NKp46+ ILC development via a cell intrinsic mechanism. Mixed foetal liver chimeras were generated in which congenically marked wild-type Rorγtgfp/+ (Ly5.1+Ly5.2+) and Rorγtgfp/+Tbx21−/− (Ly5.2) foetal liver cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into irradiated Ly5.1+/+ recipients allowing us to trace the hemopoietic origin of LTi, NKp46+ ILCs and NK cells. Eight weeks following reconstitution, T-bet-sufficient foetal liver progenitors reconstituted the NK, LTi and NKp46+ ILC compartments. In contrast, Tbx21−/− foetal liver progenitors reconstituted LTi normally, NK cells poorly, and completely failed to reconstitute NKp46+ ILCs (Fig. 1d). Thus, the similar and specific loss of NKp46+ ILCs in both intact and foetal liver chimeric mice shows that this defect is attributable to a cell-intrinsic mechanism. To determine whether T-bet influences the capacity of mature LTi cells to differentiate into NKp46+ ILC in vivo, purified innate lymphocyte subsets from Rorc(γt)gfp/+ and Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice were adoptively transferred into Rag2−/−γc−/− recipient mice that lack all ILCs15. After 14 days, transferred LTi cells and NKp46+ ILCs (Rorγt intermediate and high) were recovered from the small intestinal lamina propria. While Rorγtgfp/+ LTi cells were able to differentiate into NKp46+ ILCs, Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− cells failed to generate NKp46+ ILCs (Fig. 2a). Notably, NKp46+ ILCs generated from T-bet sufficient LTi cells did not express NK1.1 or the cytolytic molecule perforin distinguishing them from classical NK cells (data not shown). This was also the case when recipient mice were infected with C. rodentium to induce an inflammatory state (data not shown). Thus, mature LTi cells can give rise to NKp46+ ILCs in vivo in line with previous observations24 but are unable to do this in the absence of T-bet.

Figure 2. Notch and T-bet regulate the developmental pathway of innate lymphocyte populations.

a, In vivo differentiation of ILC subsets in the presence or absence of T-bet. 0.5-1 × 105 LTi cells or NKp46+ ILCs were purified from the small intestinal lamina propria of either Rorc(γt)gfp/+or Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice then adoptively transferred into Rag2γc-deficient mice. After 14 days, donor lymphocytes were isolated from the small intestinal lamina propria of recipient mice and analysed for the differentiation of innate lymphocyte populations. Data show representative profiles of one of four independent experiments with similar results. Dot plots are gated on lin−CD45+ live donor cells. b, In vitro differentiation of LTi or NKp46+ mature ILCs purified from the small intestinal lamina propria of Rorc(γt)gfp/+and Rorc(γt)gfp/+ Tbx21−/− mice cultured on OP9 or OP9-DL1 stromal cells in the presence of SCF, IL-7 and Flt3L and analysed on day 9 of culture. Data are representative of at least 2-4 independent experiments with similar results. c, T-bet expression in ILC subsets differentiated as in b.

The cues responsible for driving transition between LTi cells and NKp46+ ILCs are largely unknown, although Notch signaling has previously been implicated25,26. To further explore the relationship between T-bet and Notch in NKp46+ ILC differentiation, we cultured purified ILC populations from Rorc(γt)gfp/+ and Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice on OP9 or Notch ligand expressing OP9-DL1 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7, SCF and Flt3L and analysed their differentiation (Fig. 2b). After 9 days, wild-type LTi cells generated NKp46+ ILCs only when exposed to a Notch ligand while Tbx21−/− LTi cells failed to generate this subset. Rorc(γt)gfp/+NKp46+ ILCs generated in vitro also upregulated their expression of T-bet solely in the presence of Notch ligands (Fig. 2c). However, in the absence of T-bet or when a Notch blocking antibody was added to wild-type cultures, induction of the NKp46+ ILC population was respectively blocked or markedly reduced (Fig. 4b,c, and data not shown). Combined, this data demonstrates an unappreciated link between T-bet and Notch signaling for the differentiation of NKp46+ ILCs.

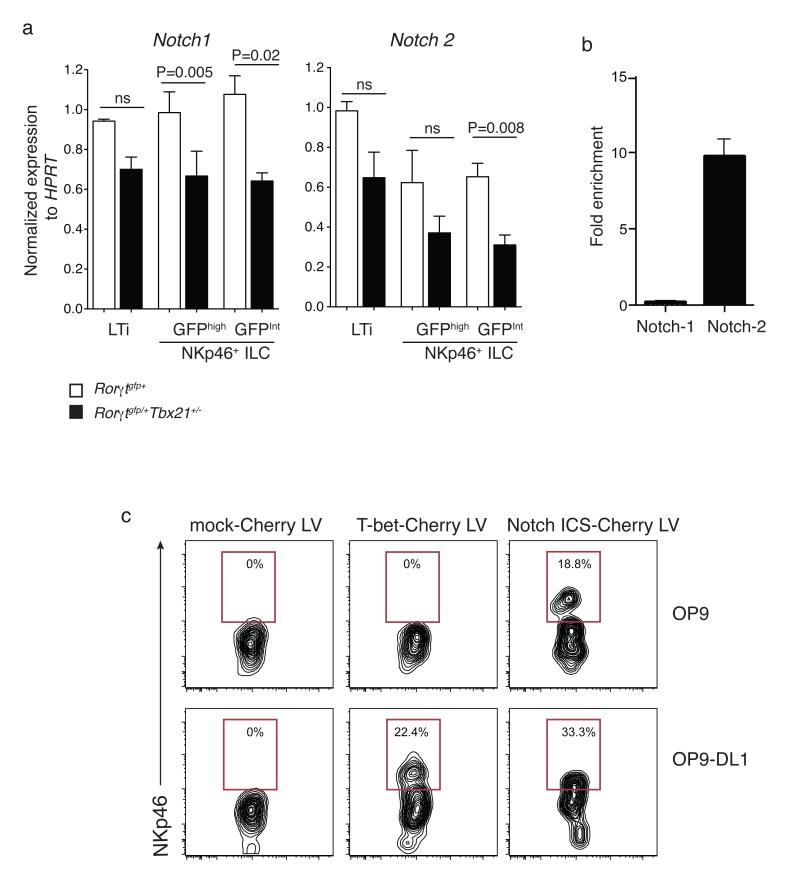

Figure 4. Notch and T-bet regulate the developmental pathway of innate lymphocyte populations.

a, Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of Notch1 and Notch2 in ILCs isolated from the small intestine of mice of the indicated genotypes. RT-PCR analyses show the mean ± s.e.m. of samples analysed in triplicate; ILC subsets show mean percent CD45+lin− (CD11c−Gr-1−CD19−CD3ε−CD45+) PI− cells ± s.e.m. isolated from small intestinal lamina propria. Data are representative of at least three similar experiments. b. Binding of T-bet within the Notch1 and Notch2 genes was analysed using ChIP. Data are the mean enrichment calculated as the percentage enrichment compared to non-immunoprecipitated input DNA ± s.d. from 3 independent samples. c. Rescue of NKp46+ ILC development in LTi cells by retroviral expression of either T-bet or Notch ICS in Tbx21−/− LTi cells and coculture on OP9 or OP9-DL1 stromal cells for 5 days. Shown are flow cytometry plots gated on live Cherry+ cells. Numbers indicate the proportion of cells within the transduced population (Cherry+) that differentiated into NKp46+ ILCs.

NKp46+ ILCs express two distinct levels of Rorγt-GFP, however the similar expression and requirement for T-bet in both populations suggests that these subsets are highly related, although the exact relationship between them remains unclear. In vitro exposure to Notch ligands showed that LTi cells generated predominantly Rorγt-GFPint cells (Fig. 2b). In contrast, adoptive transfer experiments showed the Rorγt-GFPhigh phenotype to be relatively stable and the Rorγt-GFPint NKp46+ subset produced a large proportion of Rorγt-GFPhigh cells (Fig. 2a), which suggests interconversion between these populations.

ILCs arise as progeny of LTi cells24 (Fig. 2), but the contribution of CD4+ and CD4− LTi cells to the differentiation of NKp46+ ILCs is unclear. Following the enumeration of all ILCs in Rorc(γt)gfp/+ and Rorc(γt)gfp/+Tbx21−/− mice, we found an increase in LTi cells in the gastrointestinal tract (Supplementary Fig.2). Interestingly, this increase was only observed within the CD4− LTi subset, suggesting that loss of T-bet may prevent the developmental progression specifically from CD4−LTi cells into NKp46+ ILCs (Fig. 3a,b). Indeed, using our OP9-DL1 Notch ligand culture system, NKp46+ ILCs could only be differentiated from sorted CD4− and not from CD4+ LTi cells (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. CD4− and not CD4+ LTi cells give rise to NKp46+ ILCs.

a. Frequency of CD4− and CD4+ LTi subsets isolated from the small intestine of Tbx21+/+ and Tbx21−/− mice. b, Total cell number of CD4− and CD4+ LTi cells in the small intestine of Tbx21+/+ compared with T-bet deficient mice. Data show mean ± s.e.m (n=4/group). c, CD4− LTi, CD4+LTi and NKp46+ ILCs cells were sorted from Tbx21+/+ mice and cultured on OP9-DL1 cells in the presence of IL7, SCF and Flt-3L. Differentiated cells were analyzed for NKp46 expression after 5 days. Data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results.

We further examined whether T-bet expression was also essential for other related ILC populations, such as nuocytes, in addition to it’s requirement for the development of NKp46+ ILCs (Supplementary Fig. 8)6. Similar to LTi and NKp46+ ILCs, nuocytes also expressed high levels of Id2-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 8a). However, in contrast to NKp46+ ILCs, Tbx21−/− mice showed normal nuocyte numbers, frequency and Id2-GFP expression (Supplementary Fig. 8b-d). In addition, their capacity to produce the cytokine IL-13 and mediate eosinophil recruitment was unaltered (Supplementary Fig. 8e-g). Thus, T-bet appears to be specifically involved in the regulation of NKp46+ ILCs.

To determine whether a direct interaction between T-bet and Notch was required for differentiation of NKp46+ ILCs, we first analyzed ILC populations from the small intestine of Tbx21+/+ wild-type and haploinsufficient Tbx21+/− mice for their expression of Notch1 and Notch2 (Fig. 4a). Both Notch family members exhibited a reduction in expression in NKp46+ ILCs isolated from Tbx21+/− mice (Fig. 4a). To search for putative T-bet binding sites in the Notch genes we examined published ChIPseq analysis for T-bet in Th1 cells27. This revealed a T-bet binding site to intron 2 of Notch1 and in the promoter of Notch2. To examine whether T-bet also bound in the Notch genes in ILCs we performed ChIP on in vitro cultivated NK cells, an ILC lineage that could be obtained in sufficient numbers for ChIP analysis. T-bet occupancy was only observed in Notch2 and not Notch1 (Fig. 4b.). While these data strongly suggest that T-bet directly regulates Notch2 in NKp46+ ILC differentiation, the mechanism by which T-bet controls Notch1 remains to be determined.

To further understand the relationship between T-bet and Notch-signaling in NKp46+ ILC differentiation, we expressed T-bet or the intracellular form of Notch (ICN) by lentiviral transduction into Tbx21−/− LTi cells and cultured them on OP9 or OP9-DL1 cells for 5 days (Fig. 5c). Enforced expression of T-bet was able to rescue the formation of NKp46+ ILCs from Tbx21−/− LTi cells in a Notch-signaling dependent manner. Most importantly, expression of a constitutively activated form of Notch (ICN) was sufficient to mediate differentiation of NKp46+ ILCs. The T-bet regulation of Notch2 (and potentially Notch1) identifies a novel and distinct pathway that drives the differentiation of NKp46+ ILCs from LTi cells to promote the lineage diversity observed within the innate lymphocyte family.

Figure 5. CD4−LTi cells, not CD4+LTi cells, give rise to NKp46+ ILCs.

(a) Flow cytometry of LTi subsets isolated from the small intestine of Rorc(γt)+/GFPTbx21+/+ and Rorc(γt)+/GFPTbx21−/− mice. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent CD4−LTi cells (bottom) and CD4+LTi cells (bottom). (b) Total CD4− and CD4+LTi cells in the small intestine of Rorc(γt)+/GFPTbx21+/+ and Rorc(γt)+/GFPTbx21−/− mice (n = 4 per genotype). NS, not significant; *P = 0.0083 (unpaired Student’s t-test). (c) NKp46 expression by CD4−LTi cells, CD4+LTi cells and NKp46+ ILCs sorted from wild-type mice and cultured for 5 d on OP9-DL1 cells in the presence of IL-7, SCF and Flt-3L. Data are representative of at least two experiments (mean and s.e.m. in b).

Our finding that Notch is downstream of T-bet suggests a model whereby the induction of T-bet in mature LTi cells is the critical step in defining the NKp46+ ILC lineage by enabling a response to Notch-ligand mediated cues on adjacent cells. Interestingly, Notch expression in ILCs has also been proposed to partially depend on another environmental ligand inducible transcription factor, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor26. Collectively, this implies a complex but highly regulated interplay between the gut microenvironment and innate lymphocytes in order to control gastrointestinal homeostasis.

Our data demonstrates CD4− LTi cells are the direct precursor to NKp46 ILCs and identifies T-bet as the essential transcriptional regulator of NKp46+ ILCs, a key innate cell type required for intestinal immune protection. The ability of NKp46+ ILCs to rapidly expand from LTi cells in response to T-bet/Notch-signaling shows them to be a highly specialized innate cell type and suggests NKp46+ ILC expansion may be driven by integration of signals delivered by gut microbial communities through the T-bet pathway. Our studies have implications for how modulation of T-bet expression promotes tolerance or uncontrolled immune reactions leading to intestinal disease and pathology.

METHODS SUMMARY

All mice used were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities of WEHI. C57BL/6, Ly5.1, C57BL/6 × Ly5.1 (F1), B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J (Rag1)28, Rag2tm1.1Flv × Il2rgtm1.1Flv (Rag2γc), Id2gfp 29, Rorc(γt)gfp (Rorγtgfp) 7, Tbx21−/− 30, Tbx21−/−Rorc(γt)gfp and Blimp1gfp 31 were used. Flow cytometric analyses was performed on antibody stained lymphocyte populations and analysed using a CantoII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo analysis software. Intracellular staining for cytokines was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Mice were lethally irradiated (2 × 0.55 Gy), reconstituted with a mixture of Tbx21−/− (Ly5.2+) and Tbx21+/+ (Ly5.1+/5.2+) foetal liver cells at a ratio of 1:1 and mice were allowed to reconstitute for 8 weeks. Intestinal lymphoid cells were isolated from intestine by incubations in 5mM EDTA Ca2+ Mg2+ free Hanks medium (2 × 20 min) followed by digestion with Collagenase III (2 × 30 min, 37 °C, 1 mg/ml; Worthington)/DNase I (200 μg/ml; both from Roche) and Dispase (4U/mL) then Mononuclear cells were isolated with 40%/80% Percol gradient. Purified lymphoid progenitors and ILC populations were cultured on OP9 or OP9-DL1 cells in complete IMDM supplemented with Flt3L (20 ng/ml), 2% supernatant of an IL-7-producing cell line and SCF (10 ng/mL)24. Cells were cultured for 9 days prior to analysis. Total RNA was prepared from purified ILC populations for quantative RT-PCR using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA with OligodT and thermoscript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using the SensiMix SYBR no-Rox kit (Bioline). Tissues for histological analyses were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed routinely. Immunohistological tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, sucrose infiltrated and embedded in OCT freezing medium prior to staining for CD3, B220, CD326, NKp46. Images were acquired on a LSM780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Mircoimaging) and quantified using IMARIS image analysis software (Bitplane). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired student’s t-test, two tailed.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants and fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (G.T.B. and S.L.N.); an NHMRC Dora Lush Postgraduate Research Scholarship (L.R); an NHMRC Postdoctoral Overseas Fellowship (J.R.G.); an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (S.C.), the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (G.T.B.), the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (S.L.N.); the American Asthma Foundation (J.A.W.), the Medical Research Council and the American Asthma Foundation (A.N.J.M.). We thank M. Camilleri, R. Cole, J. Cruickshank and the staff of the animal and flow cytometry facilities for technical assistance. This work was made possible through Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC IRIIS.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Sanos SL, Vonarbourg C, Mortha A, Diefenbach A. Control of epithelial cell function by interleukin-22-producing RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Immunology. 2011;132:453–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun Z, et al. Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science. 2000;288:2369–2373. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, Diefenbach A. RORγt and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin IL22-producion NKp46+ cells. Nature Immunology. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokota Y, Mansouri A, Mori S, Sugawara S, Adachi S, Nishikawa S, Gruss P. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;25:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SH, et al. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine M-J, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR. An essential function for the nuclear receptor Rorγt in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nature Immunology. 2004;5:64–72. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Q, Saenz SA, Zlotoff DA, Artis D, Bhandoola A. Cutting edge: Natural helper cells derive from lymphoid progenitors. J Immunol. 2011;187:5505–5509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawa S, et al. Lineage relationship analysis of RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Science. 2010;330:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherrier M, Ohnmacht C, Cording S, Eberl G. Development and function of intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Current opinion in immunology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynders A, et al. Identity, regulation and in vivo function of gut NKp46+RORgammat+ and NKp46+RORgammat− lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:2934–2947. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon SM, et al. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo SJ, et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klose CS, Hoyler T, Kiss EA, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. Transcriptional control of innate lymphocyte fate decisions. Current opinion in immunology. 2012;24:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin H, et al. A role for the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2009;31:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luci C, Reynders Ana, Ivanov Ivaylo I, Cognet Celine, Chiche Laurent, Chasson Lionel, Hardwigsen Jean, Anguiano Esperanza, Banchereau Jacques, Chaussabel Damien, Dalod Marc, Littman Dan R, Vivier Eric, Tomasello Elena. Influence of the transcription factor RORyt on the development fof NK46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nature Immunology. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Townsend MJ, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherrier M, Sawa S, Eberl G. Notch, Id2, and RORgammat sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:729–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nature medicine. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrett WS, et al. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell. 2007;131:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vonarbourg C, et al. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORgammat confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORgammat(+) innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 2010;33:736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Possot C, et al. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:949–958. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JS, et al. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mombaerts P, et al. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson JT, et al. Id2 expression delineates differential checkpoints in the genetic program of CD8alpha(+) and CD103(+) dendritic cell lineages. EMBO J. 2011;30:2690–2704. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neurath MF, et al. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1129–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kallies A, et al. Plasma cell ontogeny defined by quantitative changes in blimp-1 expression. J.Exp.Med. 2004;200:967–977. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.