Abstract

Disrupted cholesterol homeostasis has been reported in Alzheimer disease and is thought to contribute to disease progression by promoting amyloid β (Aβ) accumulation. In particular, mitochondrial cholesterol enrichment has been shown to sensitize to Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the increased cholesterol levels and its trafficking to mitochondria in Alzheimer disease remain poorly understood. Here, we show that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress triggered by Aβ promotes cholesterol synthesis and mitochondrial cholesterol influx, resulting in mitochondrial glutathione (mGSH) depletion in older age amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS1) mice. Mitochondrial cholesterol accumulation was associated with increased expression of mitochondrial-associated ER membrane proteins, which favor cholesterol translocation from ER to mitochondria along with specific cholesterol carriers, particularly the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. In vivo treatment with the ER stress inhibitor 4-phenylbutyric acid prevented mitochondrial cholesterol loading and mGSH depletion, thereby protecting APP/PS1 mice against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Similar protection was observed with GSH ethyl ester administration, which replenishes mGSH without affecting the unfolded protein response, thus positioning mGSH depletion downstream of ER stress. Overall, these results indicate that Aβ-mediated ER stress and increased mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking contribute to the pathologic progression observed in old APP/PS1 mice, and that ER stress inhibitors may be explored as therapeutic agents for Alzheimer disease.

Since the initial observation that feeding rabbits with a cholesterol-enriched diet leads to amyloid β (Aβ) accumulation,1 the number of studies linking cholesterol and Aβ metabolism have increased exponentially. Although the impact of cholesterol in clinical studies remains unsettled, cumulating evidence indicates increased cholesterol levels in brain from Alzheimer disease (AD) patients.2–5 Moreover, findings in animal and cultured-cell models demonstrate that cholesterol enrichment in lipid rafts fosters Aβ production6–8 and aggregation,9 and inhibits the intracellular degradation of the peptide.10 By using mouse models of cholesterol loading, namely sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP-2) transgenic mice and Niemann-Pick type C1 knockout mice, we have shown that the trafficking of cholesterol to mitochondria depletes mitochondrial glutathione (mGSH), which in turn exacerbates Aβ-induced oxidative neuronal death.11 Furthermore, in the amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS1) transgenic mouse the overexpression of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident transcription factor SREBP-2 accelerated and worsened key pathologic manifestations of AD, correlating with mitochondrial cholesterol loading and mGSH depletion.12 Consequently, in vivo mGSH recovery in APP/PS1 mice significantly reduced Tau pathology and Aβ depositions.12 Interestingly, increased mitochondrial cholesterol levels, concomitant with reduced mGSH content, also were observed in old APP/PS1 mice after Aβ accumulation,11 suggesting that Aβ per se can regulate cellular cholesterol. However, although the role of APP and the amyloidogenic processing on cholesterol homeostasis disruption has been suggested previously,2,13–15 the molecular mechanisms remain largely unknown.

Previous studies have reported that moderate ER stress can deregulate lipid metabolism.16 The cellular response to alleviate the ER stress is elicited by the stress transducers inositol-requiring protein 1 (IRE1), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and protein kinase R (PRKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) that trigger a signaling pathway called the unfolded protein response (UPR). In particular, the engagement of the PERK pathway has been involved in the activation of SREBPs.17–19 Conversely, overexpression of the chaperone glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78) has been described to inhibit the expression of SREBP-1c and SREBP-2 proteins.20 ER stress is an early event in AD and has been implicated indirectly as a mediator of Aβ neurotoxicity,21–25 whereas caspase-12 and caspase-4 have been reported as intermediates of the ER stress-specific apoptosis triggered by Aβ.26,27 Hence, these studies lead us to hypothesize that Aβ-induced ER stress might be an additional mechanism contributing to the increased brain cholesterol content observed in AD, as a result of enhanced SREBP-2 processing. By using 2- to 15-month-old APP/PS1 mice and the SH-SY5Y cell line we examined the regulatory role of ER stress on cholesterol and mGSH levels and further analyzed the impact of these alterations on neuronal death. In vivo treatment of APP/PS1 mice with ER stress inhibitors restored the mitochondrial cholesterol homeostasis, replenished mGSH, and blocked Aβ-mediated cell death and neurotoxicity. A similar degree of protection was observed in APP/PS1 mice treated with GSH ethyl ester, which prevented mGSH depletion without affecting ER stress. These data provide evidence that ER stress contributes to Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, at least in part by increasing mitochondrial cholesterol accumulation, which leads to impaired mitochondrial antioxidant defense.

Materials and Methods

APP/PS1 and SREBP-2 Mice

Breeding pairs of B6C3-Tg(APPswe,PSEN1dE9)85Dbo/J (APP/PS1) and B6;SJLTg(rPEPCKSREBF2)788Reh/J (SREBP-2) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and characterized as previously described.11 Briefly, at the time of weaning (21 days), mice were identified genetically by PCR using DNA from ear-tips and following the genotyping protocols provided by the supplier. We observed an age-dependent increase of brain cholesterol levels in female wild-type (WT) mice compared with male mice (not shown). Therefore, although female APP/PS1 mice have a more pronounced AD phenotype, in the present study we focused on male transgenic and WT mice to minimize variability caused by sex differences. All procedures involving animals and their care were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Barcelona and were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines in compliance with national and international laws and policies.

Subcellular Fractionation to Isolate Mitochondria, ER, and MAM Purification

Brains were removed of olfactory bulbs, midbrain, and cerebellum, and were homogenated in 210 mmol/L mannitol, 60 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L sodium succinate, 1 mmol/L ADP, 0.25 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.1 mmol/L EGTA, and 10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4. Homogenates were centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes. The resulting pellet (crude mitochondria) was suspended in 2 mL, loaded onto 8 mL of 30% (v/v) Percoll (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient, and centrifuged at 95,000 × g for 30 minutes. The mitochondrial pellet then was rinsed twice by centrifuging for 15 minutes at 10,000 × g. To isolate mitochondria from cell culture, 5 × 107 SH-SY5Y cells were trypsinized and rinsed first in PBS and then in hypotonic buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, 5 mmol/L KCl, and 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, pH 8.0). After centrifugation at 800 × g for 2 minutes the resulting pellet was resuspended in three volumes of hypotonic buffer and incubated for 10 minutes on ice. Then, cells were disrupted by four aspirations through a 30-gauge needle. Mannitol-sucrose-HEPES buffer (2.5×) (50 mmol/L HEPES, 525 mmol/L mannitol, 175 mmol/L sucrose, and 5 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0) was added to the lysates before centrifuging at 1500 × g for 5 minutes. The postnuclear supernatant was separated further through a 14% Percoll density gradient and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 minutes. Loose mitochondrial pellets were rinsed in 210 mmol/L mannitol, 60 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L sodium succinate, 0.1 mmol/L EGTA, and 10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4, by centrifuging for 10 minutes at 8000 × g. In both cases (brain and SH-SY5Y cells), mitochondrial purity was examined for cross-contamination with ER and plasma membrane by Western blot analysis.

ER and mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) were isolated according to the Wieckowski et al28 protocol. Postnuclear supernatant (S1) was centrifuged at 9000 × g for 10 minutes to further process supernatants (S2) and pellets (P2). The ER fraction was obtained by washing the S2 supernatant at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 hour to collect the pellet. In parallel, P2 was centrifuged twice at 10,000 × g before centrifugation on a 30% Percoll gradient to obtain the lower band, which contains mitochondria, and the upper band, which contains MAM, which were collected and washed further to remove any Percoll contaminants.

Cell Culture and Treatments

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line was obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's nutrient mixture F12 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mmol/L glutamine. Cells were plated at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/well. Twenty-four hours after plating, cells were treated with 10 μmol/L oligomeric Aβ (Bachem AG, Bubendorf, Switzerland), 2 nmol/L thapsigargin (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mmol/L 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), 50 μmol/L salubrinal (Calbiochem, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), 100 μmol/L tauroursodeoxycholic acid (Calbiochem, Merck Millipore), or 1 nmol/L gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Sigma-Aldrich). In some cases, cells were fractionated into cytosol or mitochondria on digitonin permeabilization of the plasma membrane as described previously.29

Preparation of Aβ Peptides

Human Aβ1-42 was dissolved to 1 mmol/L in hexafluoroisopropanol and aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes, then the hexafluoroisopropanol was evaporated and the peptides were stored at −20°C until use. For oligomeric assembly, concentrated peptides were resuspended in 5 mmol/L dimethyl sulfoxide and then diluted to 100 μmol/L in phenol red–free media and incubated at 4°C for 24 hours. Oligomeric forms of Aβ were confirmed by Western blot as previously described.11

GSH and Cholesterol Measurements

GSH levels in homogenates and mitochondria were analyzed by the recycling method.30 For cholesterol determination from brain, samples were extracted with alcoholic KOH, distilled water, and hexane (1:1:2, v/v/v). Appropriate aliquots of the hexane layer were evaporated and used for cholesterol measurement.31 High-performance liquid chromatography analysis was performed using a μBondapak C18 10 μm reverse-phase column (30 cm × 4 mm inner diameter; Waters Corp., Milford, MA), with a mobile phase of 2-propanol/acetonitrile/distilled water (6:3:1, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The amount of cholesterol was calculated from standard curves and the identity of the peaks was confirmed by spiking the sample with known standards. Cholesterol levels in membrane fractions from ER and MAM were quantified by the Ampex Red cholesterol assay (Invitrogen). Samples were resuspended in the homogenization buffer containing 5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) and briefly sonicated. Mitochondrial cholesterol levels in cells were determined after Aβ exposure in the presence of the 0.75 mmol/L P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1) inhibitor aminoglutethimide.

Western Blot Analysis

Samples (30 to 80 μg of protein per lane) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were probed with the antibodies listed in Table 1. After overnight incubation at 4°C, bound antibodies were visualized using horseradish-peroxidase–coupled secondary antibodies and an ECL developing kit (GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB). Densitometry of the bands was measured with QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and values were normalized to β-actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Table 1.

Details of the Primary Antibodies Used in This Study

| Antibody | Source and type | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | Rabbit polyclonal | Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO) | 1:1000 |

| Calregulin (H-170) | Rabbit polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:500 |

| Caspase-3 | Rabbit polyclonal | Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) | 1:1000 |

| Caspase-12 | Rat monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1:500 |

| CHOP | Mouse monoclonal | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| COX IV | Rabbit polyclonal | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| Cytochrome c (clone 7H8.2C12) | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:500 |

| Phospho-eIF2α | Rabbit polyclonal | Invitrogen | 1:1000 |

| eIF2α | Mouse monoclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| GAPDH (6C5) | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:5000 |

| GRP78 | Rabbit polyclonal | Stressgen (Enzo Life Science) | 1:1000 |

| HXK I (G-1) | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:200 |

| HMG-CoA reductase | Goat polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:500 |

| INSIG-1 | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| MAP2 | Mouse monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1:500 |

| MFN2 | Mouse monoclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| StARD3 | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| Na+,K+ATPase α1 | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:500 |

| PACS-2 | Goat polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:200 |

| Phospho-PERK (Thr980) | Rabbit polyclonal | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| PERK | Rabbit polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1:1000 |

| Rab5A | Rabbit polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:250 |

| Rab7 | Goat polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:250 |

| Sigma receptor (B-5) | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotech | 1:200 |

| SREBP-2 | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| StAR | Mouse monoclonal | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| VDAC | Rabbit polyclonal | Calbiochem (EMD Millipore) | 1:500 |

| β-actin | Mouse monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1:10,000 |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MFN2, mitofusin-2; PACS-2, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 2; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded blocks were prepared by sequential dehydration in graded ethanol and infiltration in paraffin before embedding. Blocks were sectioned serially at a thickness of 5 μm from −1.2 mm through −2.4 mm from Bregma. Sections were processed according to the avidin–biotin–peroxidase staining method (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After antigen retrieval, the endogenous peroxidase was blocked by exposure to 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes. Samples then were treated with the avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions and incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-ATF6 (1:500; Acris, San Diego, CA) and mouse monoclonal anti–Aβ1-42 (1:300; Sigma-Aldrich). After washing with PBS, sections were incubated for 1 hour with a biotinylated secondary antibody (1:400), followed by ABC staining for 1 hour. The immunoreaction was visualized with diaminobenzidine using a diaminobenzidine-enhanced liquid substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). TUNEL labeling was performed using the in situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany).

Immunofluorescence and Laser Confocal Imaging

Dewaxed hippocampal sections were first boiled in citrate buffer (10 mmol/L sodium citrate, pH 6.0) and incubated with 0.1 mol/L glycine/PBS for 20 minutes to reduce autofluorescence. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR; 1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse monoclonal anti–microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2; 1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), and rat monoclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:500; Calbiochem Merck Millipore). After washing in PBS, antibody staining was visualized using Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 secondary antibodies (1:400; Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Confocal images were collected using a Leica TCS SPE laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with UV excitation, an argon laser, a 63/1.32 OIL PH3 CS objective, and a confocal pinhole set at 1 Airy unit (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). All of the confocal images shown were single optical sections. Immunofluorescence intensities and colocalization coefficients were determined using MBF ImageJ software version 1.43m (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Real-Time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR amplification was performed using the iScript one-step RT-PCR kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). The primer sequences used are listed in Table 2. PCRs were run in duplicate for each sample. The relative gene expression was quantified by the ΔΔCt method.

Table 2.

Details of the Primers Used in This Study

| Name | Host | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRP78 | H | 5′-AATGACCAGAATCGCCTGAC-3′ | 5′-CGCTCCTTGAGCTTTTTGTC-3′ |

| CHOP | H | 5′-GCGCATGAAGGAGAAAGAAC-3′ | 5′-ACCATTCGGTCAATCAGAGC-3′ |

| SREBP2 | H | 5′-TGCCATTGGCCGTTTGTGTC-3 | 5′-CCCTTCAGTGCAACGGTCATTCAC-3′ |

| STAR | H | 5′-ATCTTTTCCGATCTTCTGC-3′ | 5′-CTTGGGCATCCTTAGCAAC-3′ |

| Stard4 | M | 5′-GAGAGATGGCTGACCCTGAGA-3′ | 5′-TCAGACAGTCCTTCCAGTTTGATC-3′ |

| Stard5 | M | 5′-GACGCGTCGGGCTGG-3′ | 5′-AACTCCTCAGATGGCCTCCA-3′ |

| Xbp1 | M | 5′-GGATCTCTAAAACTAGAGGCTTGGTG-3 | 5′-AAACAGAGTAGCAGCGCAGACTGC-3′ |

H, human; M, Mus musculus.

Analysis of Xbp1 mRNA Splicing

RNA was reverse-transcribed using Xbp1-specific primers, described in Table 2, that amplified a 600-bp cDNA product encompassing the IRE1 cleavage sites.32 This fragment was digested further by PstI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) to show a restriction site that is lost after IRE1-mediated cleavage and mRNA splicing. The PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel.

Pregnenolone Determination

To assess pregnenolone production, cells were plated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium phenol-free media containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mmol/L glutamine. Cells were exposed to 10 μmol/L Aβ with or without pretreatment (1 hour) with ER stress inhibitors. After 48 hours of incubation, new media containing 10 μmol/L of trilostane (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) was added to prevent further processing of pregnenolone, and cells were left to accumulate it for 48 hours. Media then was recovered and levels of the steroid hormone precursor were determined using a human pregnenolone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Diagnostics Biochem Canada, Inc., Dorchester, ON, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were normalized to total protein values.

Statistics

Results are expressed as means ± SD of the number of experiments. Statistical significance was examined using the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett or Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparisons test when required. P < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Results

Enhanced SREBP-2 Processing and Decreased ATP-Binding Cassette, Sub-Family A, Member 1 Transporter Expression Correlate with Increased Brain Mitochondrial Cholesterol Levels in APP/PS1 Mice

We first monitored the age-dependent changes in brain cholesterol levels of APP/PS1 mice. Cholesterol content in homogenate or isolated mitochondria from brains of APP/PS1 mice significantly increased at 10 months of age (Supplemental Figure S1A), consistent with previous observations.11 The increment in the sterol levels was observed in hippocampus samples from 7-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Figure 1A), whereas cholesterol levels in cerebellum, a brain area relatively unaffected in AD, remained unchanged at 10 months of age (Figure 1A). These findings were accompanied by a significant depletion of GSH in brain mitochondria of 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Supplemental Figure S1B). Western blot analysis in the final mitochondrial fraction from 10-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice showed an absence of plasma membrane and endosome markers, as well as a negligible presence of PERK and calreticulin compared with ER fraction. Thus, the contribution from cross-contamination of other organellar fractions to the higher level of mitochondrial cholesterol seen in aged APP/PS1 mice was minimized (Supplemental Figure S2).

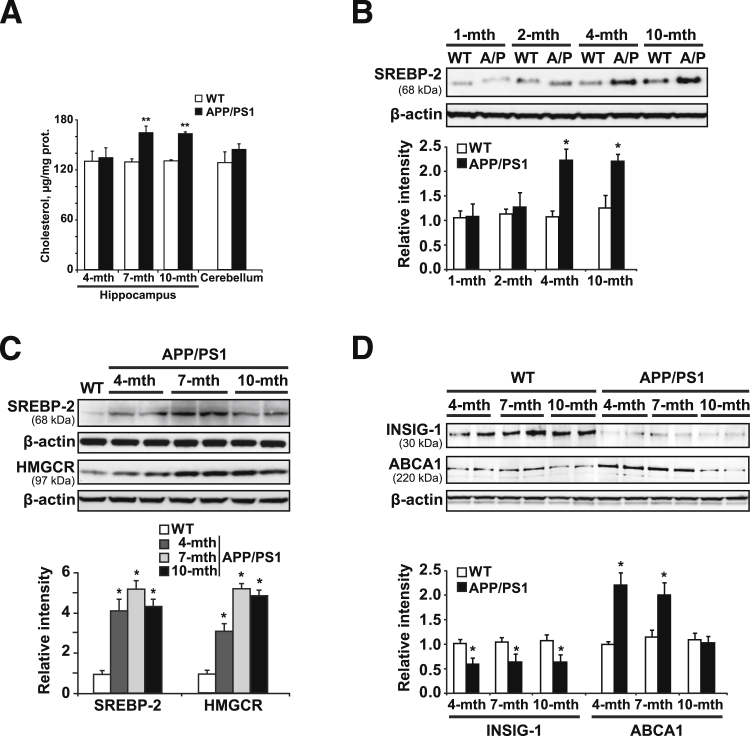

Figure 1.

Expression levels of cholesterol biosynthesis-related proteins. A: Cholesterol levels. B: Western blot analysis of SREBP-2 protein levels in brain extracts from WT mice and APP/PS1 (A/P) mice at the indicated ages. C: Western blot analysis of SREBP-2 and HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) proteins in brain extracts from 10-month-old WT mice and APP/PS1 mice at different ages. D: Representative immunoblots of INSIG-1 and ABCA1 presence in brain extracts from WT mice and APP/PS1 mice at the indicated ages. Relative intensity values are densitometric values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity normalized with the values of the corresponding β-actin bands. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT mice values by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test (A, B, and D) and one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (C) (n = 4 to 6). mth, month.

To relate these observations with pathways leading to cholesterol synthesis, we analyzed the processing of mature SREBP-2. The increase in the levels of the transcriptionally active fragment of SREBP-2 (68 kDa) was first detectable at 4 months of age (Figure 1, B and C) and correlated with an enhanced expression of its target gene encoding the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of the cholesterol synthesis pathway (Figure 1C). The expression of SREBP-2 and HMG-CoA reductase further increased in older APP/PS1 mice (Figure 1C), whereas the levels of both peptides remained unchanged in WT mice at all ages analyzed (Supplemental Figure S3A). Because SREBP activation is tightly regulated by levels of insulin-induced gene-1 (INSIG-1)17,33 we next analyzed its expression in APP/PS1 mice. As shown, transgenic mice compared with WT mice displayed decreased levels of INSIG-1 at all ages analyzed (Figure 1D). Moreover, because of the time lag between the early SREBP-2 processing (age, 4 mo) and the late increase in cholesterol levels (age, 10 mo) observed in APP/PS1 mice, we considered the contribution of alternative mechanisms in regulating cholesterol homeostasis. For instance, decreased levels of the ATP-binding cassette transporter, sub-family A, member 1 (ABCA1) have been described in brains of 11-month-old APP/PS1 mice, with accumulation of cholesterol in cultured astrocytes resulting from Aβ-induced down-regulation of ABCA1 expression.34 In turn, data from mouse models and in vitro experiments have suggested that ABCA1 may affect Aβ deposition and clearance by regulating apolipoprotein E lipidation and brain cholesterol homeostasis.35 Furthermore, despite the fact that the expression levels of this protein in AD still are under debate, with studies showing high levels of ABCA1 in hippocampal tissues from AD patients,36,37 several reports have linked ABCA1 polymorphisms to an increased risk for AD.35 Interestingly, when the levels of the protein were analyzed in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 1D), we observed an increase in the expression at 4 and 7 months of age that decreased to WT levels in 10-month-old mice. The existence of an impaired cholesterol efflux resulting from low ABCA1 levels associated with an enhanced synthesis may explain in part the cholesterol increase in old APP/PS1 mice.

Increased Expression of Mitochondrial Cholesterol Carriers in APP/PS1 Mice

Mitochondria are cholesterol-poor organelles. However, cholesterol transport to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) plays a physiological role and is a highly regulated process.38 Cholesterol trafficking to IMMs is controlled chiefly by StAR, which moves cholesterol from the outer mitochondrial membrane to the IMM for metabolism. StAR belongs to a family of proteins that contain StAR-related lipid transfer domains (StAR-related lipid transfer proteins), of which StARD3 (MLN64) and StARD4 also have been described to allow delivery of cholesterol to mitochondria. In WT mice the levels of StAR and StARD3 were maintained steadily during aging (Supplemental Figure S3B). By contrast, APP/PS1 mice displayed high levels of StARD3 at all ages analyzed compared with WT mice (Figure 2A), whereas StAR increased in 10-month-old transgenic mice (Figure 2A), concomitant to the increase of mitochondrial cholesterol observed at this age (Supplemental Figure S1A). The mRNA expression of StARD4 also was increased in 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice, whereas StARD5, which is involved in the transport of cholesterol between Golgi, ER, and plasma membrane, remained unchanged (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical analysis by confocal microscopy confirmed the increase of StAR in the hippocampus of 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Figure 2C). The double-labeling showed colocalization between StAR and the neuronal marker anti-MAP2, but not with the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (Figure 2, C and D). Similarly, significant up-regulation of StAR and StARD3 protein levels was observed in SREBP-2 transgenic mice (Figure 2E), establishing a link between induced cholesterol synthesis and mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking. Furthermore, differences in the time expression of both cholesterol carriers between APP/PS1 and Tg–SREBP-2 mice highly suggest that although StARD3 may be regulated by the transcription factor SREBP-2, the induction of StAR expression requires high levels of cholesterol, but is not directly dependent on SREBP-2 activation.

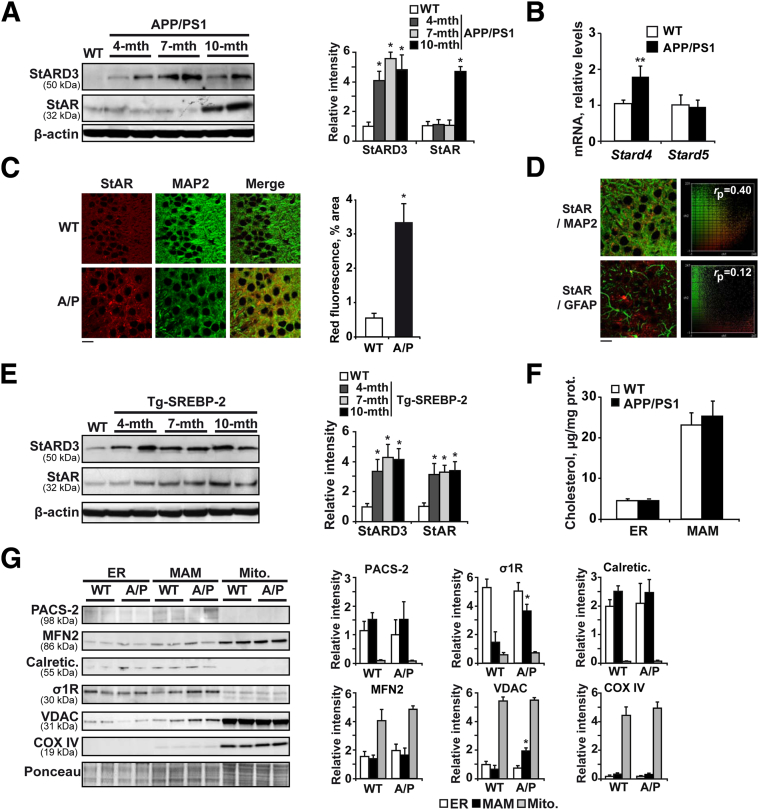

Figure 2.

Expression levels of cholesterol-transporting polypeptides. A: Representative immunoblots of StARD3 and StAR showing an increased presence of these cholesterol carriers in brain samples from APP/PS1 mice compared with 10-month-old WT mice. B: mRNA levels of StARD4 and StARD5 in brain samples from WT and APP/PS1 mice at 10 months of age analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Absolute mRNA values were determined, normalized to 18S rRNA, and reported as relative levels compared to the expression in WT mice. C: Representative confocal images of StAR (red) and MAP2 (green) immunofluorescence labeling of hippocampal sections from 10-month-old WT mice and APP/PS1 mice. D: Representative confocal images of hippocampal sections from 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice immunostained with anti-StAR (red) and anti-MAP2 or anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; green). The extent of colocalization was quantified using the linear Pearson correlation coefficient (rp); the resulting scatterplot images are shown on the right. A value of 1.0 indicates complete colocalization of two fluorescent signals. Note that StAR preferentially colocalizes with neurons labeled with anti-MAP2 compared with astrocytes labeled with anti-GFAP. E: Western blot analysis of StARD3 and StAR expression in brain from 10-month-old WT mice and Tg–SREBP-2 mice at the indicated ages. F: Total cholesterol in ER and MAMs from brain extracts of 10-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice. G: Representative immunoblots showing the expression of calreticulin (calregulin), the sigma-1 receptor (σ1R), phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 2 (PACS-2), and the mitochondrial proteins cyclooxygenase 4 (COX IV), voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein (VDAC), and mitofusin 2 (MFN2) in ER, MAMs, and mitochondria from 10-month-old WT and APP/PS1 (A/P) mice. In all Western blot analyses the densitometric values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity were normalized with the values of the corresponding β-actin bands or Ponceau Staining. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT mice values by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (A and E) and the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test (B, C, and G) (n = 3 to 6). Scale bars: 15 μm (C and D). mito., mitochondria; mth, month.

In addition to StAR-related lipid transfer proteins as mediators of mitochondrial cholesterol transport, recent studies have suggested the involvement of MAMs. MAMs are molecular hubs that regulate several aspects of mitochondrial biology, ranging from calcium transmission to lipid metabolism,39 including cholesterol homeostasis.40,41 Moreover, data from experimental AD models have shown increased MAM function as determined by cholesteryl ester and phospholipid synthesis,42 accompanied by high levels of MAM-associated proteins, including the sigma-1 receptor,43 and suggest that these interaction sites may contribute to AD pathology. To evaluate the role of MAMs on the enhanced mitochondrial cholesterol transport observed in old APP/PS1 mice, we first tested whether cholesterol enrichment in isolated MAMs was similar to that of mitochondria. As previously reported, cholesterol levels were higher in MAM fractions compared with the total content in the ER (Figure 2F). However, we did not find significant differences between WT and APP/PS1 mice in either ER or in the MAM subdomains (Figure 2F). As indicators of increased area of apposition between ER and mitochondria we next evaluated the levels of phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 2 and mitofusin-2, both are proteins that are required to regulate the contact sites between the two organelles.44,45 As shown, Western blot analysis showed similar levels of both peptides in MAMs isolated from brain extract of WT and APP/PS1 mice (Figure 2G). Conversely, the levels of the sigma-1 receptor and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein were increased significantly in MAMs from APP/PS1 mice (Figure 2G), suggesting that these MAM-associated proteins, previously proposed to facilitate cholesterol translocation from ER to mitochondria,41,46 may contribute to mitochondrial cholesterol content in APP/PS1 mice.

Early ER Stress Precedes Mitochondrial Cholesterol Accumulation in APP/PS1 Mice

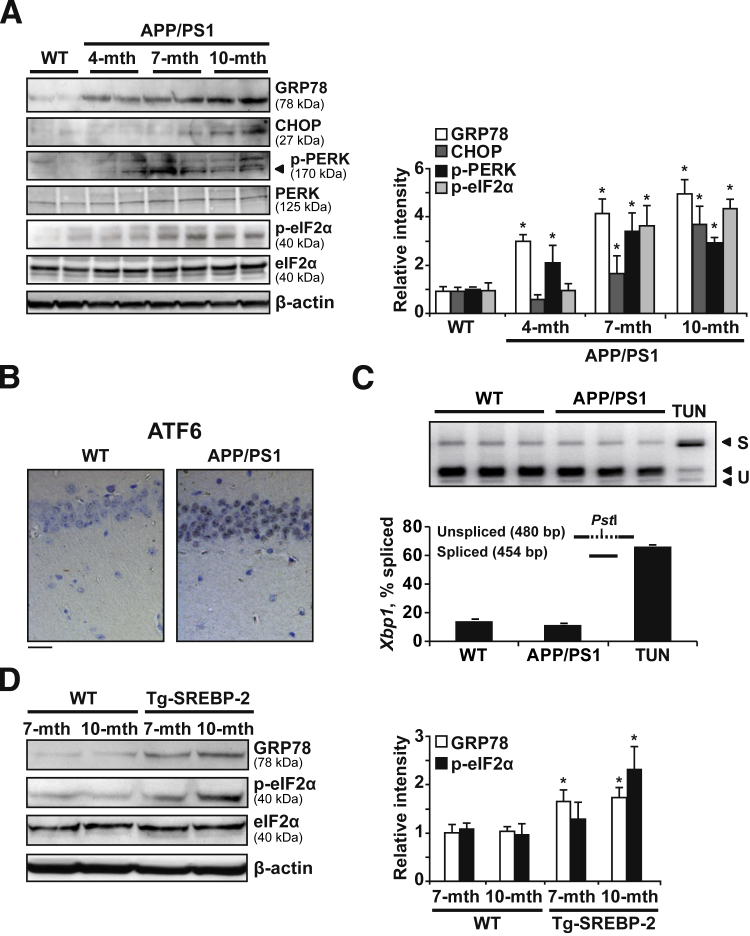

Given the cause-and-effect relationship between increased cholesterol synthesis and enhanced mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking and mGSH regulation, we aimed to analyze further the mechanism responsible for these changes. Because previous studies had shown that moderate ER stress modulates the cellular lipid content,16 we explored whether the Aβ-induced ER stress can affect cholesterol homeostasis. Although no signs of ER stress were detectable in WT mice at all of the ages analyzed (Supplemental Figure S4A), the UPR was activated in APP/PS1 mice, with markers showing age-dependent changes (Figure 3A). GRP78 and phospho-PERK were the earliest markers up-regulated at 4 months of age (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S4B), whereas eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)-2α phosphorylation and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) increase were detected in older APP/PS1 mice (Figure 3A). Moreover, Aβ loading paralleled ER stress in APP/PS1 mice, with hippocampal amyloid accumulation in intracellular compartments of 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Supplemental Figure S5). APP/PS1 mice also showed activation of the ATF6-dependent branch of UPR. ATF6 is processed by the same metalloproteases that activate SREBPs47 and although previous reports suggested that ATF6 antagonizes the activity of SREBP-2,48 we found nuclear ATF6 in hippocampal neurons from 7-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, compared with tunicamycin-treated mice, IRE1 phosphorylation and Xbp1 splicing were not observed in APP/PS1 mice (data not shown and Figure 3C). The correlation between ER stress and cholesterol accumulation also was noticed in SREPB-2 transgenic mice, which showed increased GRP78 levels and eIF2α phosphorylation compared with WT mice (Figure 3D). Thus, APP/PS1 mice showed an early UPR response that preceded the increase of cholesterol levels, the increase in the expression of mitochondrial cholesterol transporting polypeptides, particularly StAR, and mGSH depletion.

Figure 3.

APP/PS1 mice display early ER stress. A: Representative immunoblots showing the expression of the chaperonic protein GRP78 and the ER stress signaling pathway proteins PERK, phospho-PERK, eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α, and CHOP in brain extracts from 10-month-old WT mice and APP/PS1 mice at the indicated ages. B: Immunohistochemical staining of ATF6. Representative photomicrographs of CA1 hippocampus showing nuclear localization of ATF6 in 7-month-old APP/PS1 mice (n = 3). C: Analysis of Xbp1 mRNA splicing. Total RNAs from brain of 7-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice were subjected to RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. After digestion with PstI, the PCR products were resolved in a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products of Xbp1 mRNA spliced (S) remained intact (454 bp), whereas the unspliced products (U) were cut into two fragments of 289 and 191 bp, as indicated by the arrows. mRNA from liver of WT mice treated i.p. with 1 mg/kg 24 hours tunicamycin (TUN) was used as a positive control (n = 3). D: Western blot analysis of GRP78, eIF2α, and phospho-eIF2α in brain extracts from WT mice and SREBP-2 transgenic mice. In all Western blot analyses, densitometric values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity were normalized with the values of the corresponding β-actin bands. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mice values by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (A), and the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (D) (n = 6). Scale bar = 50 μmol/L (B). mth, month.

Aβ Induces ER Stress in SH-SY5Y Cells, Resulting in Increased Mitochondrial Cholesterol Influx and mGSH Depletion

Once we established that ER stress precedes the disruption in cholesterol homeostasis in APP/PS1 mice, we analyzed the link between ER stress and mitochondrial cholesterol loading by Aβ in vitro. We used soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ1-42, previously confirmed by Western blot.11 As shown, Aβ1-42 exposure increased the expression of GRP78 and CHOP at the mRNA (Figure 4A) and protein levels (Figure 4B) over time in SH-SY5Y cells. These findings were accompanied by eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 4B), confirming the involvement of the PERK branch observed in APP/PS1 mice.

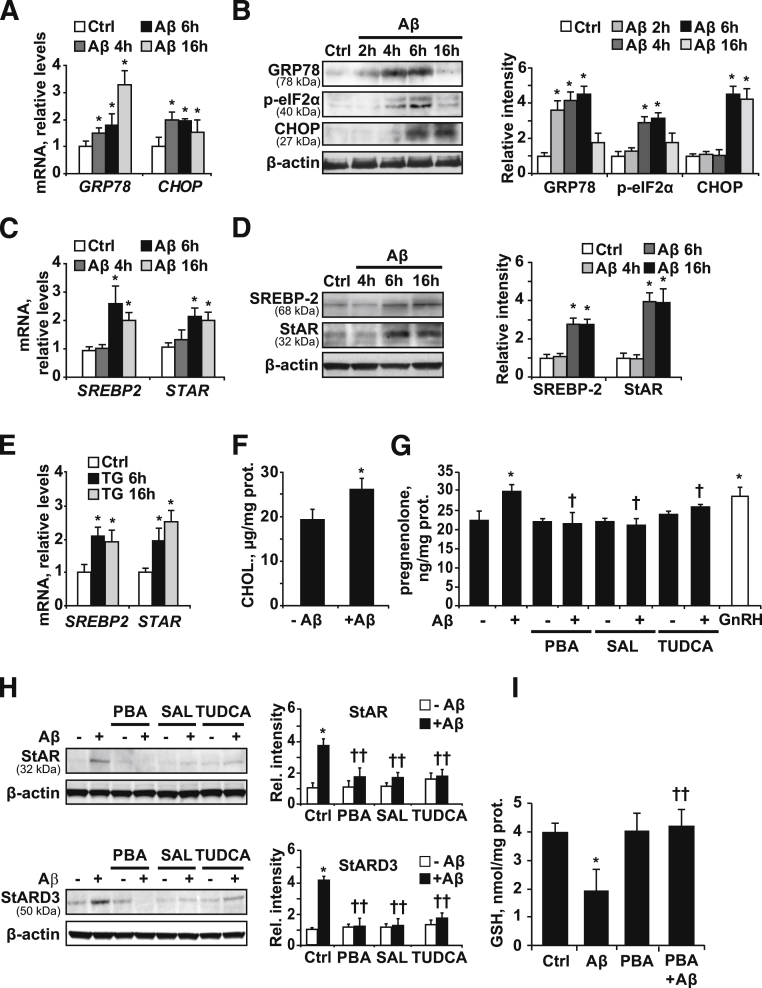

Figure 4.

ER stress induced by oligomeric Aβ1-42 promotes mitochondrial cholesterol transport and mGSH depletion in SH-SY5Y cells. GRP78, p-eIF2α, and CHOP expression levels in cells treated with 10 μmol/L Aβ at the indicated time points, analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (A) and Western blot (B). SREBP-2 and StAR expression levels after exposure to 10 μmol/L Aβ at the indicated time points, analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (C) and Western blot (D). E: mRNA levels of SREBP-2 and StAR after incubation with 2 μmol/L thapsighargin (TG) at the indicated time points, analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA values were normalized to 18S rRNA and reported as relative levels compared to the expression in WT mice. F: Mitochondrial cholesterol levels after incubation with 10 μmol/L Aβ for 48 hours, and 0.75 mmol/L inhibitor aminoglutethimide was added for the last 24 hours. G: Quantification of pregnenolone delivered to media as indicator of mitochondrial cholesterol loading. Cells were exposed to 10 μmol/L Aβ with or without 5 mmol/L PBA, 50 μmol/L salubrinal (SAL), or 100 μmol/L tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) pretreatment for 1 hour. After 48 hours of incubation new media containing 20 μmol/L of trilostane was replaced and cells were left to accumulate the steroid hormone for 48 hours. Pregnenolone levels in media were determined as described in Materials and Methods. As a positive control, cells were treated with 1 nmol/L gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) for 48 hours. Western blot analysis of the mitochondrial cholesterol carriers StAR and StARD3 in cellular extracts (H) and mitochondrial GSH levels after 4 days of 10 μmol/L Aβ incubation with or without 5 mmol/L PBA, 50 μmol/L SAL, or 100 μmol/L TUDCA pretreatment for 1 hour (I). In all of the Western blot analyses densitometric values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity were normalized with the values of the corresponding β-actin bands. ∗P < 0.05 versus control values; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus Aβ treatment values by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (A–E), the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test (F), and one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (G-I) (n = 3 to 6).

This outcome preceded the increased expression of transcription factor SREBP-2 and StAR by Aβ both at the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 4, C and D). Similar findings were observed when SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to the ER stressor thapsigargin (Figure 4E). Consistent with the function of StAR in mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking, there was a significant increase in cholesterol levels in isolated mitochondria from SH-SY5Y cells treated with Aβ for 48 hours (Figure 4F), pointing to the amyloid peptide as responsible for the mitochondrial cholesterol enrichment observed in APP/PS1 mice.

To further assess the involvement of the Aβ-induced ER stress we tested the effects of ER stress inhibitors. In steroidogenic cells, cholesterol is metabolized in the IMM by P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A) and converted into the steroid precursor pregnenolone. Mitochondrial cholesterol availability is the rate-limiting step in the steroid biosynthesis and, therefore, pregnenolone levels can be used as a gauge of the rate of mitochondrial cholesterol influx.49 In agreement with the increased mitochondrial cholesterol levels observed in isolated mitochondria, exposure to 10 μmol/L Aβ1-42 resulted in a significant increase in pregnenolone levels (Figure 4G). This increase was similar to that caused by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Figure 4G), which has been described previously to modulate steroidogenesis in SH-SY5Y cells.50 Interestingly, pre-incubation with different chemical inhibitors of ER stress, including 3 mmol/L PBA, 50 μmol/L salubrinal, or 100 μmol/L tauroursodeoxycholic acid, significantly decreased the levels of StARD3 and StAR protein induced by Aβ (Figure 4H) and prevented the increase of pregnenolone in Aβ-exposed cells (Figure 4G). As expected for mitochondrial cholesterol loading, Aβ challenge depleted mGSH levels (Figure 4I), and this effect was prevented by PBA. Thus, these findings establish a cause-and-effect relationship between ER stress triggered by Aβ and mGSH depletion.

ER Stress Contributes to in Vivo Neurotoxicity in APP/PS1 Mice Due to mGSH Depletion

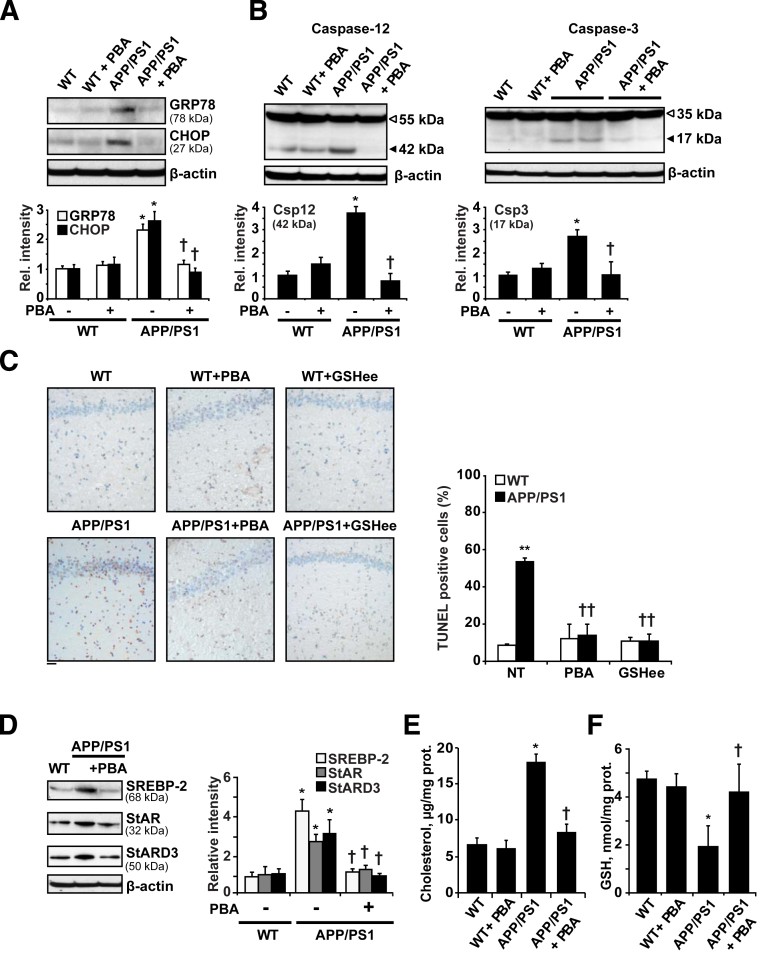

Although UPR is considered a protective mechanism, it can initiate an apoptotic cascade if the response persists over time. To analyze the contribution of ER stress to neuronal death we tested the role of PBA treatment in vivo (500 mg/kg per day), administered i.p. every 12 hours for 2 weeks, in 15-month-old APP/PS1 mice, when neurodegeneration is fully detectable. Treatment with the chaperone significantly reduced the levels of the ER stress markers GRP78 and CHOP in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 5A). Moreover, the proteolytic processing of caspase-12 and caspase-3 to their active fragments was blocked by PBA treatment (Figure 5B), resulting in reduced apoptosis in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice (Figure 5C). The use of the chaperone-like molecule also prevented the expression of SREBP-2 as well as the increase of the mitochondrial cholesterol carriers StAR and StARD3 observed in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 5D). Paralleling these effects, mitochondrial cholesterol loading (Figure 5E) and mGSH depletion (Figure 5F) in APP/PS1 mice were abolished by PBA therapy, further validating the link between ER stress and mGSH regulation.

Figure 5.

Treatment with the chemical chaperone PBA restores cholesterol homeostasis and provides protection against ER stress–induced cell death in APP/PS1 mice. Fifteen-month-old mice were treated i.p. with 500 mg/kg/d PBA for 2 weeks (n = 6 mice per group) and levels of ER stress markers, caspase activation, and cholesterol-related proteins were analyzed by Western blot. A: Representative immunoblots of GRP78 and CHOP presence in brain extracts. B: Representative immunoblots of caspase-12 and caspase-3 cleavage; arrows show fragmented caspase-12 (Csp12) (∼42 kDa) and cleaved caspase-3 active fragment (Csp3) (17 kDa). C: Representative images of apoptotic cells in hippocampus from 15-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice with or without PBA or GSHee (i.p. 1.25 mmol/kg/d for 2 weeks) assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL). D: Representative immunoblots showing a significant reduction of SREBP-2, StARD3, and StAR in brain samples from APP/PS1 mice after PBA treatment. Mitochondrial cholesterol content (E) and mGSH levels (F). In all Western blot analyses densitometric values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity were normalized with the values of the corresponding β-actin bands. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT values; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus APP/PS1 mice without treatment by one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (n = 3 to 6). Scale bar = 50 μmol/L (C).

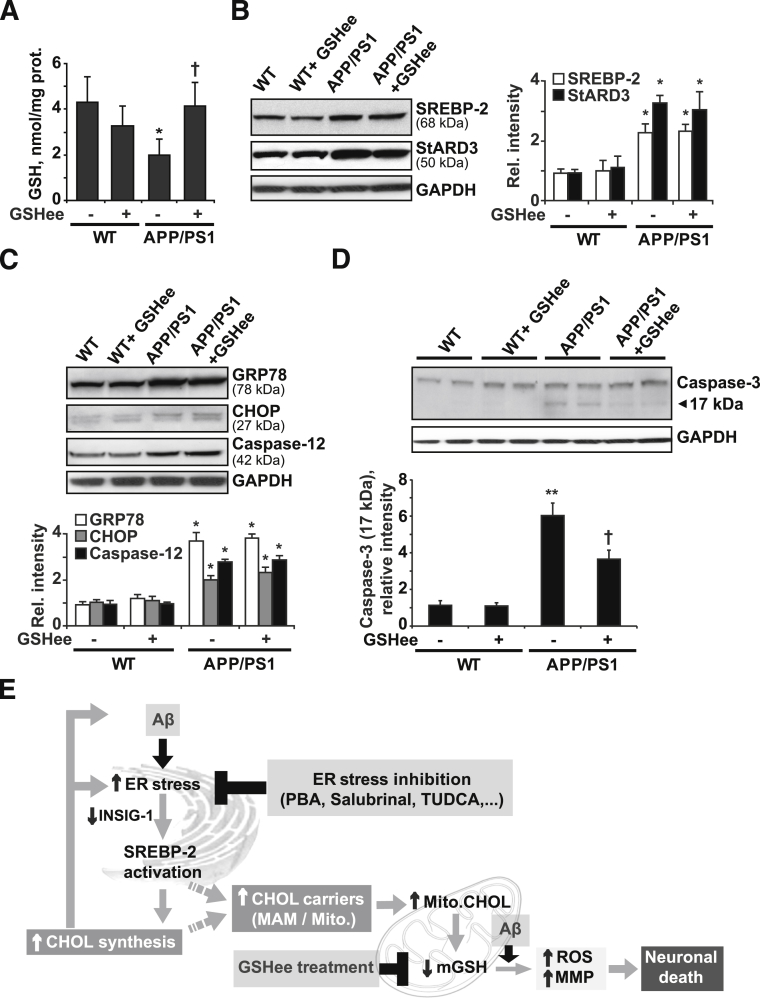

We previously showed that the mGSH content is critical in regulating the cellular response to different apoptotic stimuli including tumor necrosis factor-α, hypoxia, or Aβ peptides.51 Therefore, it is conceivable to speculate that the protective effect exerted by PBA may be owing, at least in part, to the recovery of the pool of mGSH. To further test this hypothesis mice were administered 1.25 mmol/kg/d GSH ethyl ester (GSHee) i.p. every 12 hours for 2 weeks. As shown, GSHee replenished the pool of mGSH (Figure 6A). The expression of the cholesterol-related proteins SREBP-2 and StARD3, as well as the increased levels of the ER stress markers GRP78, CHOP, and cleaved caspase-12, observed in APP/PS1 mice remained unchanged after GSHee treatment (Figure 6, B and C). However, GSHee significantly reduced the cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 6D) and prevented brain apoptosis in APP/PS1 mice to a similar extent as observed with PBA (Figure 5C). Overall, these findings suggest that ER stress contributes to in vivo Aβ neurotoxicity in APP/PS1 mice, at least in part by depletion of mGSH.

Figure 6.

In vivo GSH ethyl ester treatment. WT and APP/PS1 mice were treated i.p. with 1.25 mmol/kg/d GSHee for 2 weeks (n = 6 mice per group). A: mGSH levels. B: Representative immunoblots showing the expression levels of SREBP-2 protein and the mitochondrial cholesterol carrier StARD3 in brain extracts after GSHee treatment. C: Western blots analysis of ER stress markers GRP78 and CHOP levels and the presence of cleaved caspase-12 active fragment (42 kDa) in brain extracts after GSHee treatment. D: Representative immunoblots of caspase-3 cleavage; arrow shows cleaved active fragment (17 kDa). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels were analyzed as a loading control. In all Western blot analyses densitometric, values of the bands representing the specific protein immunoreactivity were normalized with the values of the corresponding GAPDH bands. E: Scheme illustrating the proposed model by which Aβ-induced ER stress would contribute to neuronal death through promoting cholesterol synthesis and translocation to mitochondria. This cascade of events leading to neuronal death could be counteracted by inhibiting ER stress or by restoring the mGSH levels with GSHee therapy. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT mice values; †P < 0.05 versus APP/PS1 mice values by one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test; n = (3 to 6). CHOL, cholesterol; Mito., mitochondrial; MMP, mitochondrial membrane permeabilization.

Discussion

A recent lipidomic analysis described a complex landscape of lipid alterations in specific brain regions in AD.52 Among these, disruption of cholesterol homeostasis has been described in AD,2–5 and our recent studies advanced a role for mitochondrial cholesterol in Aβ-induced neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity.11,12 Here, we analyzed the role of ER stress in cholesterol homeostasis, mitochondrial cholesterol loading, and mGSH depletion in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 6E). First, we observed that APP/PS1 mice show early ER stress and increased levels of active SREBP-2 associated with decreased expression of INSIG-1. INSIGs exert their action in the ER by binding SREBP cleavage-activating protein and preventing it from escorting SREBPs to the Golgi apparatus where the SREBPs are processed to their active forms. Interestingly, INSIG-1 is a short-lived protein, and inhibition of protein translation processes as a response to ER stress has been shown to reduce its levels severely,17 thus raising the possibility that a similar mechanism may take place in APP/PS1 mice, likely contributing to enhanced processing of SREBP-2.

Despite the presence of active SREBP-2 since 4 months of age, cholesterol accumulates only in old transgenic mice, and is first detectable in the hippocampus. A potential factor that accounts for this age-dependent difference may be ABCA1 expression, which increases in young transgenic mice but decreases in old mice. Although in-depth research would be needed to discern the exact mechanism, chronic inflammatory conditions41,42 or changes in cerebral oxysterols53,54 might account for this age-dependent decrease of ABCA1 expression.

A key feature of our findings is the increased mitochondrial cholesterol flux that correlates with depleted mGSH content. The evidence for this outcome was generated in a dual fashion. First, the increase in mitochondrial cholesterol parallels that of pregnenolone in human neuroblastoma cells challenged with Aβ peptide. Because mitochondrial cholesterol availability is the rate-limiting step in steroidogenesis,49,55 pregnenolone determination is a surrogate of mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking to IMM. Second, we examined the expression of different protein carriers that potentially involved in cholesterol transport to mitochondria. Unlike StARD3, changes in the expression of StAR were detectable in 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice, paralleling the increase of cholesterol in mitochondria, which positions StAR as most likely responsible for mitochondrial cholesterol loading. Interestingly, the immunohistologic analyses show that the increase in StAR is limited to hippocampal neurons; although we cannot exclude that an enhanced cholesterol synthesis also may occur in astrocytes, which are known to be the primary site for cholesterol loading in adult brain. The relevance of the mitochondrial cholesterol loading described in APP/PS1 mice is reinforced further by the reported presence of high StAR levels in affected brains of AD patients.56 In these studies, the enrichment in StAR was observed both in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and astrocytes. Moreover, although recent studies indicate that StARD3 regulates mitochondrial cholesterol in the absence of Niemann-Pick type C1,49 it is likely that the differential localization of StARD3 (endolysosomal) versus StAR (mitochondria) determines their contribution to mitochondrial cholesterol regulation. In addition, posttranslational modifications of StAR, including its phosphorylation at serine residues, have been described to modulate steroidogenesis.57 The impact of these factors in promoting mitochondrial cholesterol accumulation in the APP/PS1 mouse model remains to be established.

Mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking implies two events: cholesterol transfer to the outer mitochondrial membrane from extramitochondrial sources and intramitochondrial cholesterol movement from the outer mitochondrial membrane to IMM for metabolism. StAR plays an essential role in the latter. Indeed, germline StAR deficiency in mice results in lethal congenital adrenal lipoid hyperplasia,58 meaning that other StAR-related lipid transfer members cannot replace StAR deficiency. A remaining question, however, is how does cholesterol transfer to the outer mitochondrial membrane to be available for StAR? We found increased levels of the sigma-1 receptor and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein, both MAM-associated proteins, which have been shown to interact and collaborate with StAR in the transfer of cholesterol from ER to mitochondria.41,46 The responsiveness of MAM to ER stress has been described in Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis59; in particular, the sigma-1 receptor has been reported to regulate ER/mitochondrial Ca2+ mobilization under ER stress conditions.60 Moreover, in addition to these possibilities, caveolin-1 has recently been shown to regulate mitochondrial cholesterol homeostasis.55 However, its putative contribution to Aβ-mediated mitochondrial cholesterol loading remains to be investigated. On the other hand, overexpression of StARD4 in mouse hepatocytes also has been reported to stimulate bile acid synthesis,61 supporting its role of cholesterol transport to mitochondria. Furthermore, by using cholesterol-containing liposomes as donors, a recent study62 showed that recombinant StARD4 accelerates cholesterol transfer to isolated liver mitochondria. Consistent with these studies, we found a 1.5- to 2-fold increase of Stard4 mRNA levels in 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice whereas Stard5 levels remained unchanged, consistent with its inability to transfer cholesterol to mitochondria.63,64 Previous data have indicated that StARD5 expression was up-regulated by ER stress63; however, the transcriptional induction of StARD5 is mediated by XBP1,65 a signal transducer that was unprocessed and therefore inactive in the ER stress response displayed by APP/PS1 mice.

We observed an early activation of the UPR, coinciding with the burst of Aβ generation in 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice, and the induction of cholesterol synthesis, indicating that Aβ-induced ER stress can play a role in this alteration. In support of this link, we observed that Aβ-induced ER stress in SH-SY5Y cells stimulates the expression of SREBP-2 and StAR. The ER stressor thapsigargin reproduced these findings, confirming and extending the initial observations describing a link between ER stress and cholesterol synthesis.16,66 Moreover, Aβ exposure resulted in accumulation of mitochondrial cholesterol and pregnenolone, indicating that Aβ promotes cholesterol flux to mitochondria. The efficacy of different ER stress inhibitors in normalizing the expression of StARD3 and StAR and reducing the hormone levels, further proved that this effect was mediated via ER stress. Consistent with these data, we recently provided compelling evidence in hepatocytes that StAR is an ER stress target gene whose expression, induced by tunicamycin, is prevented by tauroursodeoxycholic acid.67 Finally, we observed that the Aβ-enhanced mitochondrial cholesterol influx is accompanied by significant mGSH depletion. The link between these events, namely increased cholesterol and mGSH depletion, is owing to the sensitivity of the mGSH carrier to changes in membrane dynamics induced by cholesterol accumulation in mitochondrial membranes.68 The reduction of mGSH levels was prevented by the chemical chaperone PBA, suggesting a key role of Aβ-induced ER stress in controlling the mitochondrial antioxidant defense.

APP/PS1 mice display specific UPR signaling, characterized by selective PERK and ATF6 activation, without IRE1α phosphorylation and Xbp1 processing. Although the underlying mechanisms contributing to this particular UPR branch activation are unknown, initial observations have described that mutations in PS1 increased the vulnerability to ER stress owing to a down-regulation of the UPR, caused by disturbed function of the IRE1α.69 Whether this particular UPR signaling is a specific feature of APP/PS1 mice has yet to be confirmed.

ER stress–mediated cell death has been linked consistently to Aβ neurotoxicity.21,23,24 Consistent with these findings, APP/PS1 mice showed increased processing of caspase-12 and caspase-3 associated with neuronal death, which was reduced significantly by inhibiting ER stress. Moreover, in vivo treatment with PBA also normalized the expression of SREBP-2 and that of StAR and StARD3 in APP/PS1 mice, preventing mitochondrial cholesterol accumulation. Recent studies in Tg2576 and APP/PS1 mice show that chronic administration of PBA is accompanied by clearance of Aβ, reduced Tau pathology, and reversal of learning deficits.70–72 In addition to its established role as an anti-ER stress agent, PBA has been shown to inhibit histone deacetylases, which may contribute to PBA-mediated effects by restoring the transcription of proteins involved in synaptic plasticity and structural remodeling. Histone deacetylase inhibitors also have been described to modulate cholesterol homeostasis, favoring cholesterol trafficking and degradation.73–75 However, the fact that other ER stress inhibitors such as salubrinal and tauroursodeoxycholic acid can modulate cholesterol homeostasis minimizes the potential contribution of histone deacetylase inhibition by PBA, further supporting an ER stress–dependent mechanism.

We observed a significant recovery of the mGSH content in cells and APP/PS1 mice that was associated with PBA-induced cholesterol normalization. Given the key role of mGSH in controlling the oxidative stress generated in mitochondria,51 we inferred that part of the ER stress–mediated cell death in the transgenic mice resulted from a compromised mitochondrial antioxidant defense that sensitizes cells to Aβ insult. To confirm this hypothesis, mice were administered GSHee, which significantly recovered the mitochondrial pool of GSH in APP/PS1 mice. As expected, the treatment did not modify the levels of ER stress or the increased brain cholesterol content displayed by the transgenic mice, but significantly reduced caspase-3 cleavage and neuronal death, to the same extent as PBA treatment, highlighting the key role of mGSH in regulating ER stress–mediated neuronal death. It is worth noting that Tg–SREBP-2 mice also showed ER stress associated with enhanced mitochondrial cholesterol loading and depleted mGSH levels,11 whereas no signs of apoptosis or Aβ accumulation were observed in these mice during aging,12 indicating that altered cholesterol homeostasis per se is not sufficient to initiate the disease.

Taken together, our findings point to ER stress as a link between Aβ and cholesterol up-regulation and subsequent mitochondrial trafficking (Figure 6E). Moreover, although the relative contribution of neuronal and glial cells has to be established, the histochemical analyses show an increased presence of StAR and nuclear ATF6 in the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer of transgenic mice, indicating that deregulated cholesterol homeostasis and ER stress is present in neurons. In addition, the data uncover mGSH depletion as a key mechanism of ER stress-mediated neurotoxicity in APP/PS1 mice. This view is of particular relevance given recent findings suggesting a feed-forward loop between ER stress and Aβ processing in AD,76 with the expected consequences of mitochondrial cholesterol loading and mGSH depletion contributing to Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity. Thus, therapeutic strategies targeting ER stress and resulting in the restoration of mGSH may be of significance in the treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Carmen Garcia-Ruiz, Montserrat Mari, and Albert Morales for critical comments and suggestions and Susana Nuñez for her help with mice care.

Footnotes

Supported in part by Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica grants SAF2010-15760 (A.C.) and SAF2009-11417 and SAF2012-34831 (J.C.F.-C.), the Fundació Marató TV3 (J.C.F.-C.), Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant PI041804 (J.C.F.-C.), the Research Center for Alcoholic Liver and Pancreatic Diseases of the NIH/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant P50AA011999-15 (J.C.F.-C.), the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (A.C. and J.C.F.-C.), and Formación de Personal Investigador (FPI) fellowships from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (E.B.-C., A.B., and L.M.).

This work was developed, in part, at the Esther Koplowitz Center (Barcelona, Spain).

Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Anna Fernández, Email: josecarlos.fernandezcheca@iibb.csic.es.

Jose C. Fernández-Checa, Email: checa229@yahoo.com.

Anna Colell, Email: anna.colell@iibb.csic.es.

Supplemental Data

Increased cholesterol levels and depleted mGSH content in 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice. Total cholesterol (A) and GSH (B) levels of brain homogenate and isolated mitochondria from WT and APP/PS1 transgenic mice at the indicated ages. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT mice values by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 6 to 8). mth, month.

Mitochondria isolated from brains of WT and APP/PS1 mice. After cellular subfraction, the purity of mitochondria was confirmed by determining in homogenate (Homo.), ER, or mitochondria (Mito.) the distribution of specific markers such as PERK and calreticulin (ER), Na+/K+-ATPase α1 (plasma membrane), Rab5a (early endosomes), Rab7 (late endosomes/lysosomes), and cyclooxygenase 4 (COX-IV; mitochondria) using immunoblot analysis. The densitometric values of the bands representing the specific antibody immunoreactivity were expressed as relative intensity compared with homogenate values (n = 3).

Stable expression levels of cholesterol-related proteins in WT mice. Representative immunoblots of SREBP-2 and HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) (A) and the cholesterol carriers StAR and StARD3 (B) in brain extracts from WT and APP/PS1 mice at the indicated ages. The densitometric values of the bands representing the specific antibody immunoreactivity were normalized to the values of the corresponding β-actin band and expressed as relative intensity compared with 4-month-old WT mice values. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus 4-month-old WT mice values by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (n = 3). mth, month.

Undetectable signs of UPR response in WT mice. A and B: Representative immunoblots showing the expression of the chaperonic protein GRP78 and the ER stress signaling pathway proteins PERK, phospho-PERK, eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α, and CHOP in brain extracts from WT and APP/PS1 (A/P) mice at the indicated ages. The densitometric values of the bands representing the specific antibody immunoreactivity were normalized to the values of the corresponding β-actin band and expressed as relative intensity compared with WT mice values. ∗P < 0.05 versus 4-month-old mice values; †P < 0.05 versus WT mice values by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test (n = 3). mth, month.

Age-dependent Aβ accumulation in APP/PS1 mice. Representative photomicrographs of hippocampus labeled with human anti–Aβ1-42 and counterstained with hematoxylin (n = 3). Scale bar = 100 μm.

References

- 1.Sparks D.L., Scheff S.W., Hunsaker J.C., 3rd, Liu H., Landers T., Gross D.R. Induction of Alzheimer-like beta-amyloid immunoreactivity in the brains of rabbits with dietary cholesterol. Exp Neurol. 1994;126:88–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutler R.G., Kelly J., Storie K., Pedersen W.A., Tammara A., Hatanpaa K., Troncoso J.C., Mattson M.P. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandaru V.V., Troncoso J., Wheeler D., Pletnikova O., Wang J., Conant K., Haughey N.J. ApoE4 disrupts sterol and sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer's but not normal brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong H., Callaghan D., Jones A., Walker D.G., Lue L.F., Beach T.G., Sue L.I., Woulfe J., Xu H., Stanimirovic D.B., Zhang W. Cholesterol retention in Alzheimer's brain is responsible for high beta- and gamma-secretase activities and Abeta production. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panchal M., Loeper J., Cossec J.C., Perruchini C., Lazar A., Pompon D., Duyckaerts C. Enrichment of cholesterol in microdissected Alzheimer's disease senile plaques as assessed by mass spectrometry. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:598–605. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osenkowski P., Ye W., Wang R., Wolfe M.S., Selkoe D.J. Direct and potent regulation of gamma-secretase by its lipid microenvironment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22529–22540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801925200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalvodova L., Kahya N., Schwille P., Ehehalt R., Verkade P., Drechsel D., Simons K. Lipids as modulators of proteolytic activity of BACE: involvement of cholesterol, glycosphingolipids, and anionic phospholipids in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36815–36823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehehalt R., Keller P., Haass C., Thiele C., Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip C.M., Elton E.A., Darabie A.A., Morrison M.R., McLaurin J. Cholesterol, a modulator of membrane-associated Abeta-fibrillogenesis and neurotoxicity. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:723–734. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C.Y., Tse W., Smith J.D., Landreth G.E. Apolipoprotein E promotes beta-amyloid trafficking and degradation by modulating microglial cholesterol levels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2032–2044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez A., Llacuna L., Fernandez-Checa J.C., Colell A. Mitochondrial cholesterol loading exacerbates amyloid beta peptide-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6394–6405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4909-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbero-Camps E., Fernandez A., Martinez L., Fernandez-Checa J.C., Colell A. APP/PS1 mice overexpressing SREBP-2 exhibit combined Abeta accumulation and tau pathology underlying Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3460–3476. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm M.O., Grimm H.S., Patzold A.J., Zinser E.G., Halonen R., Duering M., Tschape J.A., De Strooper B., Muller U., Shen J., Hartmann T. Regulation of cholesterol and sphingomyelin metabolism by amyloid-beta and presenilin. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1118–1123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q., Zerbinatti C.V., Zhang J., Hoe H.S., Wang B., Cole S.L., Herz J., Muglia L., Bu G. Amyloid precursor protein regulates brain apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism through lipoprotein receptor LRP1. Neuron. 2007;56:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierrot N., Tyteca D., D'Auria L., Dewachter I., Gailly P., Hendrickx A., Tasiaux B., Haylani L.E., Muls N., N'Kuli F., Laquerriere A., Demoulin J.B., Campion D., Brion J.P., Courtoy P.J., Kienlen-Campard P., Octave J.N. Amyloid precursor protein controls cholesterol turnover needed for neuronal activity. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:608–625. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colgan S.M., Hashimi A.A., Austin R.C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid dysregulation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J.N., Ye J. Proteolytic activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein induced by cellular stress through depletion of Insig-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45257–45265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobrovnikova-Marjon E., Hatzivassiliou G., Grigoriadou C., Romero M., Cavener D.R., Thompson C.B., Diehl J.A. PERK-dependent regulation of lipogenesis during mouse mammary gland development and adipocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16314–16319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808517105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colgan S.M., Tang D., Werstuck G.H., Austin R.C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress causes the activation of sterol regulatory element binding protein-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1843–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kammoun H.L., Chabanon H., Hainault I., Luquet S., Magnan C., Koike T., Ferre P., Foufelle F. GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress-induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1201–1215. doi: 10.1172/JCI37007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J.H., Won S.M., Suh J., Son S.J., Moon G.J., Park U.J., Gwag B.J. Induction of the unfolded protein response and cell death pathway in Alzheimer's disease, but not in aged Tg2576 mice. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42:386–394. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.5.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoozemans J.J., van Haastert E.S., Nijholt D.A., Rozemuller A.J., Scheper W. Activation of the unfolded protein response is an early event in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10:212–215. doi: 10.1159/000334536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreiro E., Resende R., Costa R., Oliveira C.R., Pereira C.M. An endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptotic pathway is involved in prion and amyloid-beta peptides neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umeda T., Tomiyama T., Sakama N., Tanaka S., Lambert M.P., Klein W.L., Mori H. Intraneuronal amyloid beta oligomers cause cell death via endoplasmic reticulum stress, endosomal/lysosomal leakage, and mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chafekar S.M., Hoozemans J.J., Zwart R., Baas F., Scheper W. Abeta 1-42 induces mild endoplasmic reticulum stress in an aggregation state-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2245–2254. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa T., Zhu H., Morishima N., Li E., Xu J., Yankner B.A., Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hitomi J., Katayama T., Eguchi Y., Kudo T., Taniguchi M., Koyama Y., Manabe T., Yamagishi S., Bando Y., Imaizumi K., Tsujimoto Y., Tohyama M. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and Abeta-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:347–356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieckowski M.R., Giorgi C., Lebiedzinska M., Duszynski J., Pinton P. Isolation of mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1582–1590. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Checa J.C., Ookhtens M., Kaplowitz N. Effect of chronic ethanol feeding on rat hepatocytic glutathione. Compartmentation, efflux, and response to incubation with ethanol. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:57–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI113063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27:502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan I.W., Culbreth P.H., Burtis C.A. Determination of free, total, and esterified cholesterol by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1979;162:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calfon M., Zeng H., Urano F., Till J.H., Hubbard S.R., Harding H.P., Clark S.G., Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelking L.J., Kuriyama H., Hammer R.E., Horton J.D., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L., Liang G. Overexpression of Insig-1 in the livers of transgenic mice inhibits SREBP processing and reduces insulin-stimulated lipogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1168–1175. doi: 10.1172/JCI20978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canepa E., Borghi R., Vina J., Traverso N., Gambini J., Domenicotti C., Marinari U.M., Poli G., Pronzato M.A., Ricciarelli R. Cholesterol and amyloid-beta: evidence for a cross-talk between astrocytes and neuronal cells. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:645–653. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf A., Bauer B., Hartz A.M. ABC transporters and the Alzheimer's disease enigma. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akram A., Schmeidler J., Katsel P., Hof P.R., Haroutunian V. Increased expression of cholesterol transporter ABCA1 is highly correlated with severity of dementia in AD hippocampus. Brain Res. 2010;1318:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim W.S., Bhatia S., Elliott D.A., Agholme L., Kagedal K., McCann H., Halliday G.M., Barnham K.J., Garner B. Increased ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression in Alzheimer's disease hippocampal neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:193–205. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rone M.B., Fan J., Papadopoulos V. Cholesterol transport in steroid biosynthesis: role of protein-protein interactions and implications in disease states. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:646–658. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashi T., Rizzuto R., Hajnoczky G., Su T.P. MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashi T., Fujimoto M. Detergent-resistant microdomains determine the localization of sigma-1 receptors to the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria junction. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:517–528. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marriott K.S., Prasad M., Thapliyal V., Bose H.S. Sigma-1 receptor at the mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane is responsible for mitochondrial metabolic regulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:578–586. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.198168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Area-Gomez E., Del Carmen Lara Castillo M., Tambini M.D., Guardia-Laguarta C., de Groof A.J., Madra M., Ikenouchi J., Umeda M., Bird T.D., Sturley S.L., Schon E.A. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:4106–4123. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedskog L., Pinho C.M., Filadi R., Ronnback A., Hertwig L., Wiehager B., Larssen P., Gellhaar S., Sandebring A., Westerlund M., Graff C., Winblad B., Galter D., Behbahani H., Pizzo P., Glaser E., Ankarcrona M. Modulation of the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interface in Alzheimer's disease and related models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmen T., Aslan J.E., Blagoveshchenskaya A.D., Thomas L., Wan L., Xiang Y., Feliciangeli S.F., Hung C.H., Crump C.M., Thomas G. PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:717–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Brito O.M., Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell A.M., Chan S.H. The voltage dependent anion channel affects mitochondrial cholesterol distribution and function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;466:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye J., Rawson R.B., Komuro R., Chen X., Dave U.P., Prywes R., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng L., Lu M., Mori K., Luo S., Lee A.S., Zhu Y., Shyy J.Y. ATF6 modulates SREBP2-mediated lipogenesis. EMBO J. 2004;23:950–958. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charman M., Kennedy B.E., Osborne N., Karten B. MLN64 mediates egress of cholesterol from endosomes to mitochondria in the absence of functional Niemann-Pick Type C1 protein. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1023–1034. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosati F., Sturli N., Cungi M.C., Morello M., Villanelli F., Bartolucci G., Finocchi C., Peri A., Serio M., Danza G. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone modulates cholesterol synthesis and steroidogenesis in SH-SY5Y cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;124:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mari M., Morales A., Colell A., Garcia-Ruiz C., Fernandez-Checa J.C. Mitochondrial glutathione, a key survival antioxidant. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2685–2700. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan R.B., Oliveira T.G., Cortes E.P., Honig L.S., Duff K.E., Small S.A., Wenk M.R., Shui G., Di Paolo G. Comparative lipidomic analysis of mouse and human brain with Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2678–2688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown J., 3rd, Theisler C., Silberman S., Magnuson D., Gottardi-Littell N., Lee J.M., Yager D., Crowley J., Sambamurti K., Rahman M.M., Reiss A.B., Eckman C.B., Wolozin B. Differential expression of cholesterol hydroxylases in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34674–34681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heverin M., Bogdanovic N., Lutjohann D., Bayer T., Pikuleva I., Bretillon L., Diczfalusy U., Winblad B., Bjorkhem I. Changes in the levels of cerebral and extracerebral sterols in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:186–193. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300320-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bosch M., Mari M., Herms A., Fernandez A., Fajardo A., Kassan A., Giralt A., Colell A., Balgoma D., Barbero E., Gonzalez-Moreno E., Matias N., Tebar F., Balsinde J., Camps M., Enrich C., Gross S.P., Garcia-Ruiz C., Perez-Navarro E., Fernandez-Checa J.C., Pol A. Caveolin-1 deficiency causes cholesterol-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic susceptibility. Curr Biol. 2011;21:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Webber K.M., Stocco D.M., Casadesus G., Bowen R.L., Atwood C.S., Previll L.A., Harris P.L., Zhu X., Perry G., Smith M.A. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR): evidence of gonadotropin-induced steroidogenesis in Alzheimer disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2006;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kil I.S., Lee S.K., Ryu K.W., Woo H.A., Hu M.C., Bae S.H., Rhee S.G. Feedback control of adrenal steroidogenesis via H2O2-dependent, reversible inactivation of peroxiredoxin III in mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2012;46:584–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caron K.M., Soo S.C., Wetsel W.C., Stocco D.M., Clark B.J., Parker K.L. Targeted disruption of the mouse gene encoding steroidogenic acute regulatory protein provides insights into congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11540–11545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sano R., Annunziata I., Patterson A., Moshiach S., Gomero E., Opferman J., Forte M., d'Azzo A. GM1-ganglioside accumulation at the mitochondria-associated ER membranes links ER stress to Ca(2+)-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2009;36:500–511. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shioda N., Ishikawa K., Tagashira H., Ishizuka T., Yawo H., Fukunaga K. Expression of a truncated form of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein, sigma1 receptor, promotes mitochondrial energy depletion and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23318–23331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.349142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Ren S., Wong E., Marques D., Redford K., Gil G., Hylemon P., Pandak W.M. Intracellular cholesterol transporter StarD4 binds free cholesterol and increases cholesteryl ester formation. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1409–1419. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700537-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korytowski W., Rodriguez-Agudo D., Pilat A., Girotti A.W. StarD4-mediated translocation of 7-hydroperoxycholesterol to isolated mitochondria: deleterious effects and implications for steroidogenesis under oxidative stress conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;392:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soccio R.E., Adams R.M., Maxwell K.N., Breslow J.L. Differential gene regulation of StarD4 and StarD5 cholesterol transfer proteins. Activation of StarD4 by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 and StarD5 by endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19410–19418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Ren S., Hylemon P.B., Redford K., Natarajan R., Del Castillo A., Gil G., Pandak W.M. Human StarD5, a cytosolic StAR-related lipid binding protein. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1615–1623. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400501-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez-Agudo D., Calderon-Dominguez M., Medina M.A., Ren S., Gil G., Pandak W.M. ER stress increases StarD5 expression by stabilizing its mRNA and leads to relocalization of its protein from the nucleus to the membranes. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2708–2715. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M031997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng Z., Zhang C., Zhang K. Role of unfolded protein response in lipogenesis. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:203–207. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]