Abstract

The ability to visualize fluorescent HIV-1 particles within the nuclei of infected cells represents an attractive tool to study the nuclear biology of the virus. To this aim we recently developed a microscopy-based fluorescent system (HIV-IN-EGFP) that has proven valid to efficiently visualize HIV-1 complexes in the nuclear compartment and to examine the nuclear import efficiency of the virus. The power of this method to investigate viral events occurring between the cytoplasmic and the nuclear compartment is further shown in this study through the analysis of HIV-IN-EGFP in cells expressing the TRIMCyp restriction factor. In these cells the HIV-IN-EGFP complexes are not detected in the nuclear compartment, while treatment with MG132 reveals an accumulation of HIV-1 complexes in the cytoplasm. However, the Vpr-mediated transincorporation strategy used to incorporate IN fused to EGFP (IN-EGFP) impaired viral infectivity. To optimize the infectivity of the HIV-IN-EGFP, we used mutated forms of IN (E11K and K186E) known to stabilize the IN complexes and to partially restore viral infectivity in transcomplementation experiments. The fluorescent particles produced with the modified IN [HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E)] show almost 30% infectivity as compared to wild-type NL4.3. Detailed confocal microscopy analysis revealed that the newly generated viral particles resulted in HIV-1 complexes significantly smaller in size, thus requiring the use of brighter fluorophores for nuclear visualization [HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E)]. The second-generation visualization system HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E), in addition to allowing direct visualization of HIV-1 nuclear entry and other viral events related to nuclear import, preserves intact viral properties in terms of nuclear entry and improved infectivity.

Introduction

Recent advances in fluorescence microscopy made it possible to shed light on several aspects of HIV-1/cell interactions.1–7 Fluorescent HIV-1 is obtained through labeling of specific viral proteins that may differ based on the replication step to enable visualization. In fact, HIV-1 Gag-GFP fusion proteins were employed to analyze the kinetics of viral assembly in producing cells4 and entry during infection5; Vpr-GFP containing HIV-1 has been used to define viral events in the cytoplasm following viral entry.1,7,8

To monitor HIV-1 in the nuclear compartment fluorescent labeling of IN was exploited by at least two groups.2,3 One method developed by Arhel et al.2 exploits the biarsenical FlAsh dye to label IN containing a tetracysteine motif in the open reading frame. This visualization tool was used to monitor viral trafficking in living cells mainly in the cytoplasm and near the nuclear membrane. A second strategy to visualize nuclear HIV-1 complexes was developed by Albanese et al.3 through Vpr-mediated transincorporation of IN fused to EGFP (HIV-IN-EGFP). The latter experimental tool made it possible to determine preferential localization of HIV-1 complexes in decondensed regions of the chromatin and near the nuclear border.3 Moreover, the HIV-IN-EGFP visualization system was applied as a direct approach to evaluate HIV-1 nuclear import, as an alternative to the commonly used indirect method that uses PCR quantification of the 2-LTR DNA viral forms.9,10

However, as observed by others, Vpr-mediated transincorporation of exogenous wild-type IN into HIV-1 containing a catalytically inactive form of IN does not reconstitute the original HIV-1 levels of infectivity.11–15 This result might be explained by improper formation of functional IN tetramers. In fact, during HIV-1 infections IN forms multimers, and a minimal requirement of a tetramer formation of IN is necessary for proper catalysis of integration. Hare et al.15 demonstrated that specific IN mutations (E11K and K186E) may generate stabilized IN complexes resulting in increased infectivity in Vpr-mediated transcomplementation experiments.

Here we show that modification of the original HIV-IN-EGFP system with the E11K-K186E IN mutations reported by Hare et al.15 produced more functional viral particles. Independent of their infectivity levels the original and the newly developed visualization systems preserve the same nuclear import properties as HIV-1. This study proves the power of the HIV-IN-EGFP method as a tool to evaluate viral events occurring between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartment of infected cells.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

Proviral clone plasmids pNL4.3R-E-Luc and pD64E were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent program. pD64N/D116N was made by sequentially introducing D64N and D116N mutations into the pNL4.3R-E-Luc. Vpr-IN-EGFP was previously described.16 The IN-E11K and IN-K186E mutations were introduced into Vpr-IN constructs using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The Vpr-IN-RFP plasmid was made through PCR amplification of the RFP and substitution of EGFP into the Vpr-IN-EGFP.

Virus production

Viruses and viral vectors were produced by transfecting 293T cells with PEI reagent.16 Viruses were produced by transfecting 25 μg of proviral DNA (pNL4.3R-E-Luc, pD64E, or pD64N/D116N) with 5 μg of VSV-G envelope (ratio 5:1). For transincorporated viruses 16 μg of proviral DNA (pNL4.3, D64E, or D64N/D116N) was transfected with 8 μg of Vpr-IN constructs and 4 μg of VSV-G envelope (ratio 4:2:1). For viruses containing two Vpr constructs [Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP+Vpr-IN(K186E)-EGFP] 4 μg of each construct was used.

Viral vectors were produced by cotransfecting the transfer vectors (pRRL.cPPT.SIN.LucWPRE or pSIN.Lenti.H2B-RFP) with the packaging plasmid (pCMVΔ8.91, pCMVΔ8.91 IND116N), VSV-G, and Vpr-IN-EGFP constructs in a relative ratio of 5:4:1:1. For EV (EV/IN-EGFP) the same plasmid ratio was used except for transfer vector, which was omitted. All viral supernatants were collected at 48 h posttransfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore), and quantified for RT activity using the PERT assay.16

Infection for imaging analysis and infectivity assay

For imaging experiments 100,000 HeLa-P4 cells were plated onto 15-mm coverslips in complete medium a day before infection. Equal amounts of virus (0.1–3 RTU) were added to a final volume of 1.5 ml in each well, followed by spinoculation at 1,400×g for 2 h at 16°C followed by incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 2 h. Fresh medium was added to cells and incubated for 4 more h and treated with 0.25% Trypsin+EDTA (1×) (GIBCO Invitrogen) for 1 min at 37°C to remove unentered virions. Cells were fixed and immunostained for nuclear lamin B (antilamin B antibodies, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) as described elsewhere3 with primary lamin B antibodies (Abcam). Coverslips were mounted on a clear glass slide by using Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA).

Infectivity assays were performed by treating 30,000 293T cells in a 24-well plate for 2 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator with viral supernatants containing 0.1–0.2 RT units.17 At 3 or 5 days postinfection cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity by using the dual-glow luciferase assay system (Promega). Relative light units (RLU) were normalized for total protein concentration of lysates through the Bradford method.

Image acquisition

Three-dimensional (3D) images of the fixed cell nucleus were obtained through the Leica TCS SP5 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a galvanometric stage and a 63.3×/1.4 NA HCX PL APO oil-immersion objective. The laser lines used for excitation are as follows: λ=488 nm for EGFP/SFGFP, λ=543 nm for RFP, and λ=633 nm for Alexa-633. Fluorescence emission was collected in the ranges of 495–550, 560–620, and 644–795 nm for EGFP/SFG, Tag-RFP, and Alexa-633, respectively. For two- and three-color analysis, a sequential image acquisition was used to reduce crosstalk between different signals below 5%. Nuclear volumes were acquired as described in Albanese et al.,3 at a z-step size of 0.3 μm or 0.1 μm where mentioned. Images were deconvolved by using the Huygens essential software using experimental PSF. Multichannel images were contrast stretched (linearly) and assembled with ImageJ (NIH.gov).

Image analysis and intensity graphs

Z-stack confocal images covering the 3D cellular volume were loaded onto the Image-J platform and after contrast stretching of images (linearly) nuclear fluorescent HIV-1 spots were counted. Spots that were present in more than two z-stacks for the same x–y position within the nuclear compartment defined by lamin B staining were considered nuclear HIV-1 complex signals. Nuclear HIV-1 signals were counted in the entire z-stacks obtained from each individual cell and averaged to obtain the number of HIV-1/nucleus counts. For cytoplasmic HIV-IN-EGFP intensity analysis, a line of interest (LOI) was drawn in the center point of each spot in its brightest z-plane and the results for intensity values were determined through the measurement plugin as the maximum, minimum, and average intensity values of HIV-IN-EGFP within the LOI.

Results

Imaging analysis of the HIV-IN-EGFP nuclear visualization system

To verify that the HIV-IN-EGFP nuclear complexes reported by Albanese et al.3 preserve properties similar to HIV-1, a series of experiments was performed. First, we verified the cellular localization of IN-EGFP transferred in target cells through empty vectors particles (EV) containing no viral genome. Fluorescent EVs (EV/IN-EGFP) were produced by transfecting HEK293T cells with the pCMVΔ8.91 packaging construct, the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope (VSV-G) for pseudotyping, and the Vpr-IN-EGFP construct to transincorporate IN-EGFP. As control two additional supernatants were produced: (1) a viral vector (VV/IN-EGFP) produced from cells transfected with the same constructs as for EV/IN-EGFP plus a lentiviral genome (pRRL.SIN.cPPT.SFFV.Luc-WPRE) and (2) a supernatant obtained from cells transfected exclusively with VSV-G and Vpr-IN-EGFP as control for unspecific nonviral IN-EGFP signals (IN-EGFP).

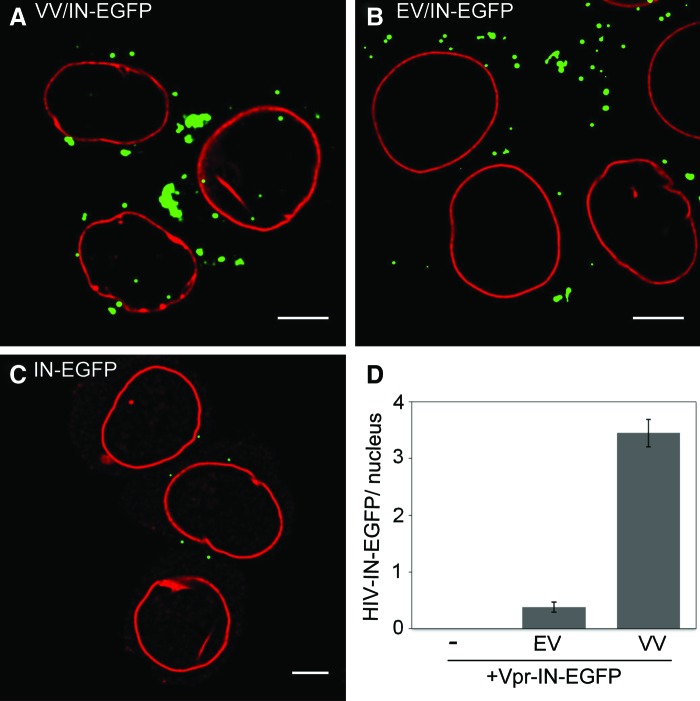

Cells infected with the control VV/IN-EGFP show an average of 3.3 viral complexes per nucleus (Fig. 1A and D) as reported before.3 Conversely, cells incubated with EV/IN-EGFP without viral genome show 10-fold less (n=0.35) IN-EGFP complexes (Fig. 1B and D). Finally, no nuclear complexes were detected in cells treated with IN-EGFP supernatants (Fig. 1C and D). These results support the notion that EGFP signals detected in the nuclei of cells treated with HIV-IN-EGFP are specifically produced following infection with viral particles and do not derive from either IN-EGFP aggregates released from virus-producing cells or viral complexes lacking the genome.

FIG. 1.

Detection of nuclear HIV-IN-EGFP complexes. Confocal images of HeLa-P4 cells incubated for 6 h with (A) viral vectors containing IN-EGFP (VV/IN-EGFP), (B) EV containing IN-EGFP (EV/IN-EGFP), and (C) supernatant from cells transfected with Vpr-IN-EGFP and VSV-G. Nuclear lamin B (red). Scale bar in (A), (B), and (C)=5 μm. (D) Number of nuclear IN-EGFP complexes in (A), (B), and (C). Shown are normalized data of a representative experiment from five independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard error. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

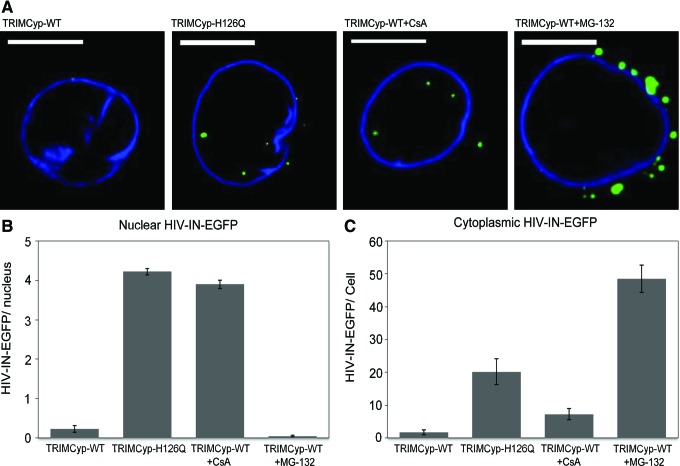

To further examine the viral properties of HIV-IN-EGFP, we used cells restricted for infection by TRIMCyp, the Old World primate factor blocking HIV-1 infection soon after viral entry.18 Fluorescent microscopy analysis of HIV-IN-EGFP was performed in TZM-bl cells expressing either TRIMCyp wild-type or a mutated inactive form (TRIMCyp-H126Q).19 In cells expressing TRIMCyp few nuclear HIV-1 complexes could be detected in the nuclei, while an average of 4.2 HIV-1 complexes per nuclei could be detected by using the same viral stock in TRIMCyp-H126Q expressing cells (Fig. 2A and B). Treatment of TRIMCyp cells with cyclosporine A (CsA), a compound that blocks the TRIMCyp-mediated restriction, results in reversion of TRIMCyp activity on HIV-IN-EGFP as indicated by a similar number of fluorescent nuclear complexes as in TRIMCyp-H126Q cells (Fig. 2A and B). Finally, since TRIMCyp restriction is associated with proteasome activity,20,21 imaging analysis was performed in TRIMCyp cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. In these cells, as in the untreated cells, HIV-1 complexes could not be detected in the nuclei while a striking accumulation of HIV-IN-EGFP complexes were visible in the cytoplasm around the nuclear envelope (Fig. 2A, right panel). Quantification of HIV-IN-EGFP complexes outside the nuclear compartment indeed demonstrates that TRIMCyp cells treated with MG132 carry at least 200-fold more viral complexes in the cytoplasm than in TRIMCyp-untreated cells and 2-fold more than TRIMCyp-H126Q cells (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

HIV-IN-EGFP intracellular localization in TRIMCyp expressing cells. (A) HIV-IN-EGFP confocal detection after 6 h infection of TZM-bl cells expressing TRIMCyp, TRIMCyp H126Q, and TRIMCyp treated with 5 μM cyclosporine A (CsA) or 20 μM MG-132. Scale bars=10 μm. (B) Number of nuclear HIV-IN-EGFP for each condition in (A) from 30 infected cells. (C) Number of cytoplasmic HIV-IN-EGFP for each condition in (A). Counts were obtained through the automatic 3D spot counting plugin of the ImageJ platform (NIH.gov). Results in (B) and (C) are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars denote standard error. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

Therefore, these data demonstrate that HIV-IN-EGFP is physiologically restricted by TRIMCyp. Moreover, the simultaneous detection of HIV-1 complexes both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm provides direct evidence of the role of proteasomes in TRIMCyp-restricted cells.

Infectivity of HIV-1 transcomplemented viruses

The HIV-IN-EGFP virions are obtained by Vpr-mediated incorporation of IN-EGFP in HIV-D64E viruses carrying a mutated IN (D64E).3 The infectivity of IN-EGFP transcomplemented D64E viruses was evaluated: by referring to Vpr-IN transcomplementation as 100%, similar efficiency was obtained with Vpr-IN-EGFP (115%) (Table 1). However, the infectivity of both viruses compared to the NL4.3 virus is around 3% (Table 1). To investigate the impact of Vpr-IN transcomplementation we evaluated the infectivity of wild-type viruses (NL4.3) following Vpr-mediated incorporation of IN and IN-EGFP. As shown in Table 1, transcomplementation with either IN or IN-EGFP decreased NL4.3 infectivity almost 4-fold.

Table 1.

Infectivity of Viruses Transincorporated with Indicated Constructs

| Vpr-IN constructsa | % of D64E complementationb | % infectivity for D64E virusc | % infectivity for NL4.3 WT virusd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vpr-IN | 100 | 3.32 (0.6) | 28.9 (4.9) |

| Vpr-IN-EGFP | 115.5 (13.2) | 4.19 (0.4) | 37.8 (5.1) |

Values represent average percentage of at least three individual experiments with standard error in parentheses.

Luc values relative to Vpr-IN complementation of D64E mutant viruses.

Luc values of D64E mutant viruses transincorporated with indicated Vpr-IN constructs relative to NL4.3Luc R-E-.

Luc values of NL4.3Luc R- E- virus transincorporated with indicated Vpr-IN constructs relative to NL4.3Luc R-E-.

Therefore, consistent with previous reports11–14 these data demonstrate that Vpr-mediated incorporation of either the native IN or IN fused to EGFP has a detrimental effect on viral infectivity.

Functional tetramerization of HIV-IN-GFP rescues viral infectivity

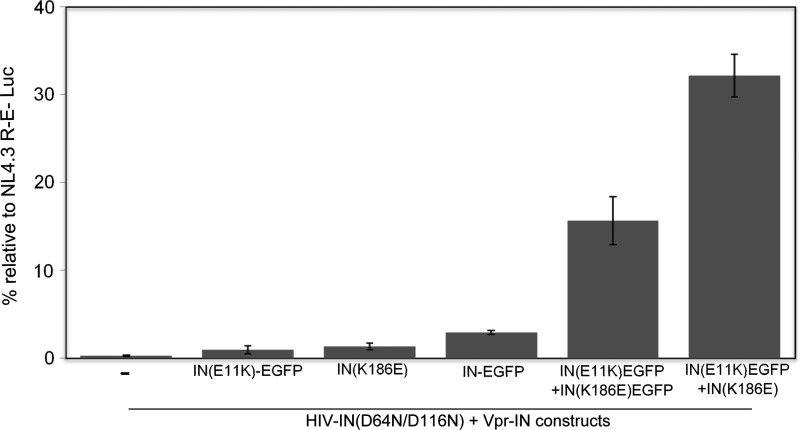

It has recently been demonstrated that tetramerization of IN can be stabilized by introducing specific modifications at the dimer–dimer interface of IN.15 Specific mutations, E11K and K186E, have been suggested to produce more stable tetramers that better complement viruses mutated in IN (D64N/D116N).15 Based on this evidence EGFP containing viruses were produced through Vpr-mediated incorporation of IN carrying the described functional tetramerization mutations (E11K and K186E) (Table 2). The infectivity of the virus containing both Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP and Vpr-IN(K186E)-EGFP constructs, HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E)EGFP, showed almost 15% infectivity, thus almost 5-fold more than the original HIV-IN-EGFP (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

HIV-1 Viruses Produced Through Vpr-Mediated Transincorporation

| Virus | Vpr-IN constructs |

|---|---|

| HIV-IN-EGFP | Vpr-IN-EGFP |

| HIV-IN(K)EGFP | Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP |

| HIV-IN(E) | Vpr-IN(K186E) |

| HIV-IN(E)EGFP | Vpr-IN(K186E)-EGFP |

| HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E)EGFP | Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP+Vpr-IN(K186E)-EGFP |

| HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E) | Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP+Vpr-IN(K186E) |

FIG. 3.

Infectivity of HIV-IN-EGFP modified with functional tetramerization mutations, E11K and K186E. Luciferase activity (RLU) produced by 293T cells 3 days postinfection with equal viral titer (RT activity) of NL4.3-R-E-Luc and pNL4.3-IN(D64N/D116N) alone or transincorporated with the indicated Vpr-IN constructs. Luciferase RLU values were normalized for protein concentration (Bradford assay) and expressed as percentage of infectivity with respect to NL4.3 infections. Results are an average of at least five independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error.

Nevertheless, transcomplementation with functional tetramers of mutated IN not fused to EGFP produces at least 30% infectivity15 (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid). Thus a virus was produced by transincorporation of a Vpr-IN construct containing a single EGFP, Vpr-IN(K)EGFP, while the other construct does not contain EGFP, Vpr-IN(K186E). This virus, HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E), shows at least double infectivity when compared to the virus containing the two EGFP constructs (Fig. 3). In addition, viruses carrying the individual Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP or Vpr-IN(K186E)-EGFP constructs were also tested showing no transcomplementation efficacy, thus proving the specific requirement of functional tetramer formation to produce infectivity.

Finally, to control the proper internalization of the Vpr constructs the viruses were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-IN antibodies showing specific incorporation of the Vpr-IN constructs (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fluorescence visualization properties of the HIV-1 containing functionally tetramerized integrase

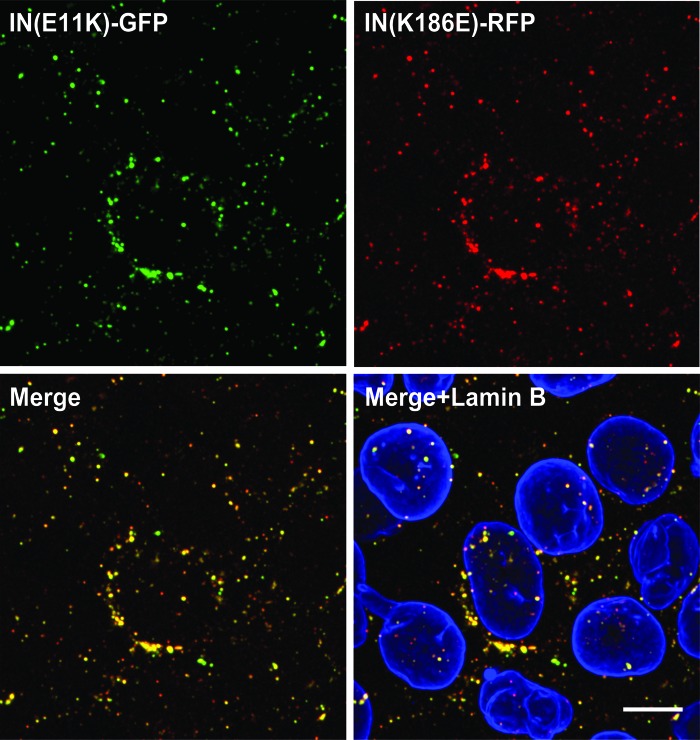

The HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E) virus showing the highest infectivity values was then analyzed by fluorescent confocal microscopy to evaluate its visualization properties. The incorporation of both functional tetramerization mutants, IN-E11K and IN-K186E, was initially evaluated by producing virions with Vpr constructs containing different fluorophores: Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP and Vpr-IN(K186E)-RFP (Fig. 4). Following infection of HeLa-P4 cells the colocalization patterns of IN E11K-EGFP with IN K186E-RFP (Fig. 4, merge panel) were analyzed by semiautomated software (coloc2 a plugin in ImageJ-NIH Gov). Infected cells showed a significant percentage of colocalizing fluorescent signals (82%), thus confirming the simultaneous incorporation of both IN(E11K) and IN(K186E) in the majority of the viral particles.

FIG. 4.

Colocalization of IN E11K-EGFP and IN K186E-RFP in fluorescent viral complexes. HeLa-P4 cells infected 6 h after infection with pNL4.3-IN(D64N/D116N) transincorporated with Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP and Vpr-IN(K186E)-RFP and immunostained for nuclear lamin B. Upper panels: IN(E11K)-EGFP (λ=488 nm) (left) and IN(K186E)-RFP (λ=546 nm) (right). Lower panels: merged images of IN E11K-GFP and IN K186E-RFP (left) and lamin B (λ=633 nm) (right). Scale bar=10 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

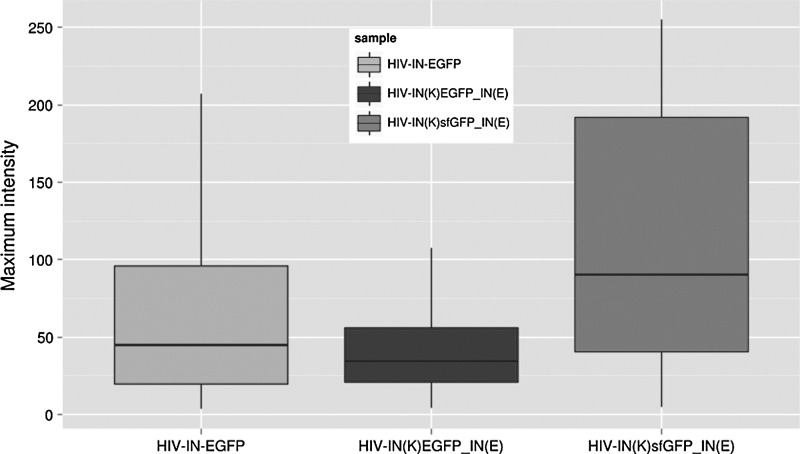

A comparative analysis of the fluorescence intensity signals produced by the original HIV-IN-EGFP3 and the newly developed HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E) was performed (see Materials and Methods) and the cumulative frequency was calculated. Results in Fig. 5 reveal that similar amounts of viral supernatant generate different fluorescent intensity signals in infected cells with HIV-IN-EGFP complexes being significantly brighter (p-value=4.041e-14) than HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E). Therefore, to increase the fluorescence intensity signal the conventional EGFP in the Vpr-IN(E11K)-EGFP construct was replaced with a brighter EGFP, superfolder GFP,22 to produce the HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) virions. Analysis of the fluorescence intensity revealed a significant increase in fluorescence intensity patterns of HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) if compared to both HIV-IN-EGFP (p-value<2.2e-16) and HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E) (p-value<2.2e-16).

FIG. 5.

Comparative analysis of fluorescence intensities produced by HIV-IN-EGFP, HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E), and HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E). HeLa-P4 cells infected with equal viral titer (RT activity) of HIV-IN-EGFP, HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E), and HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) were analyzed in 3D cellular volumes for intensity of HIV-1 complexes by ImageJ (NIH gov) (see Materials and Methods). Maximum intensity values of 500 cytoplasmic spots (from three independent experiments) are represented in a box-and-wisker plot indicating the median, the interquartile range, and upper and lower adjacent values for each sample. A two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to compare the three possible sample pairs and calculate p-values: 4.04×10−14 for HIV-IN-EGFP vs. HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E); 2.2×10−16 for HIV-IN-EGFP vs. HIV-IN(K)sfEGFP_IN(E); and 2.2×10−16 HIV-IN(K)EGFP_IN(E) vs. HIV-IN(K)sfEGFP_IN(E).

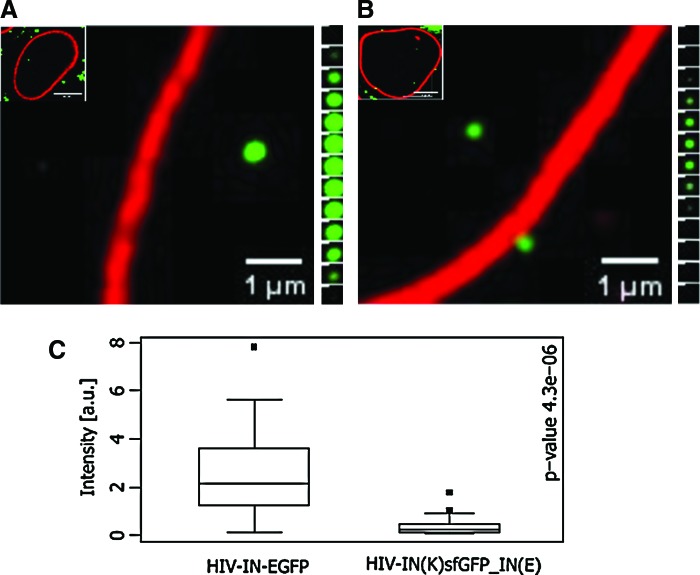

The HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) was then verified for detectability at the nuclear level. Similar to HIV-IN-EGFP as reported by Albanese et al.,3 the complexes were visible within the nuclear compartment defined by lamin B staining (Fig. 6). As defined for the minimal requirement in the nuclear detection of HIV-1 fluorescent complexes, the green signals were acquired in more than two confocal z-planes at a 0.3 μm distance from each other. In the course of the experiments we observed that the z-volumes of the newly developed HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) were smaller than the original HIV-IN-EGFP as revealed by the smaller size of the green fluorescent spots (compare Fig. 6A and B), thus requiring image acquisition at a higher sampling frequency (0.1 μm distance). To perform an unbiased comparative analysis of the nuclear HIV-1 complexes, a spot-counting software, PICs-Manager, was developed as an ImageJ plugin (Supplementary Fig. S3). This software accurately detects nuclear fluorescent spots and quantifies their intensity and size within the nuclear volume delimited by nuclear lamin B (Supplementary Fig. S3). Through semiautomated analysis, PICs-Manager made it possible to identify the intensity patterns for the nuclear viral complexes showing that the fluorescent intensity of the intranuclear HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) was substantially reduced with respect to HIV-IN-EGFP complexes (p-value=0.00018) (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Intranuclear detection of HIV-1 viral complexes. Confocal images of HeLa-P4 cells 6 h after infection with (A) HIV-IN-EGFP or (B) HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) and immunostained for lamin B (red). Scale bar=5 μm. (A) and (B), right insets: z-stacks nuclear volumes acquired 0.1 μm distances; images were deconvolved and linearly stretched for intensity of the green channel. Scale bar=0.2 μm. (C) Intensity values for intranuclear HIV-IN-EGFP and HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) as determined by PICs-manager (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. S3); Wilcoxon test p-values are reported (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. S3). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

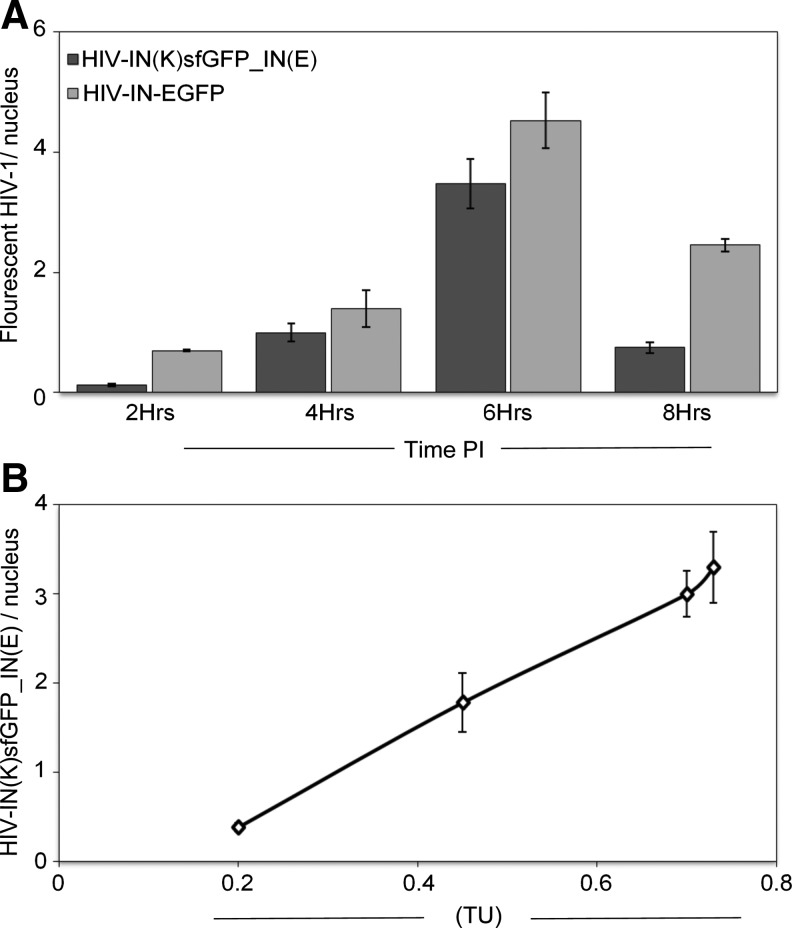

Furthermore, a comparative analysis of the nuclear entry kinetic of both HIV-IN-EGFP and HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) was performed at the same time points used to obtain maximal detection numbers for HIV-IN-EGFP (2, 4, 6, and 8 h) in Albanese et al.3 Notably, the kinetics of nuclear accumulation was similar for both viruses, showing increasing numbers of nuclear HIV-1 complexes until 6 h after infection. After 6 h the number of HIV-1 complexes decreases more rapidly in HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E)-infected cells (Fig. 7A). In addition, as for the HIV-IN-EGFP, the sensitivity to TRIMCyp was verified with HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E), showing the same restriction profile (compare Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S4).

FIG. 7.

Kinetics of HIV-1 complexes detected in the nuclei of infected cells. (A) Numbers of HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) (dark gray bars) or HIV-IN-EGFP (light gray bars) detected per nucleus in cells infected with respective viruses at the indicated time points postinfection (PI). (B) Quantification of HIV-1 complexes per nucleus of HeLa-P4 cells infected with different amounts of IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) carrying a viral vector expressing H2B-RFP. The same population of infected cells was evaluated 6 h postinfection for HIV-1 complexes nuclear content (GFP) and 48 h postinfection for TU (RFP). In (A) and (B), a representative experiment of two independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error.

Finally, the quantity of nuclear HIV-1 complexes was correlated with transduction efficiency. To measure the transduction efficiency of HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E), the fluorescent virus was produced with a lentiviral transfer vector (pSIN lenti-H2B-RFP) expressing a fluorophore, RFP, to allow evaluation of the percentage of infected cells. Hence, cells infected with scalar amounts of HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) viral vectors expressing H2B-RFP were analyzed either at 6 h for HIV-IN-EGFP nuclear complexes or after a further 48 h for infectivity through the percentage of RFP-positive cells. With a viral titer containing 2.8 RTU (10 times more than the amount of virus used in Fig. 3) almost 70% RFP-positive cells could be detected (0.7 transduction units, TDU). At this percentage of infected cells an average of 3.3 HIV-1 nuclear complexes could be observed (Fig. 7B). Scalar amounts of viral supernatants (1.4 and 0.7 RTU) produced 45% (0.45 TDU) and 20% (0.2 TDU) of infected cells showing, respectively, 1.8 and 0.4 HIV-1 complexes per nucleus (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the number of HIV-1 fluorescent complexes detected in the nuclei of infected cells correlates with the titer of the HIV-IN(K)sfGFP_IN(E) virus used to infect cells.

Discussion

Fluorescent microscopy analysis of HIV-1 makes it possible to study the spatial and temporal distribution of viral events during active infection. Emerging evidence suggests that the virus acquires specific 3D distribution in the nuclear compartment3,16,23 and that the specific nuclear location might be relevant for HIV-1 biology including viral latency.16,23 During the past decade enormous progress has been accomplished in defining nuclear events during the HIV-1 replication cycle. Yet, the molecular mechanisms defining the viral nuclear import or determining the tethering of the virus to gene-rich chromatin regions deserve further study to be completely understood.

As demonstrated by the numerous discoveries obtained by labeling HIV-1 with fluorophores, imaging techniques offer powerful tools to study this virus. Nevertheless, attempts to visualize HIV-1 in the nuclear compartment represented a challenging task. So far fluorescent systems allowing nuclear visualization of HIV-1 complexes exploit integrase labeling. One system, reported by Arhel et al.,2 was used to monitor viral trafficking in living cells mainly at the cytoplasmic and near the nuclear membrane. However, HIV-1 complexes could not be examined in depth due to the frequent disappearance of fluorescent signals within the nuclear compartment.2 This problem was overcome due to analysis by superresolution fluorescent microscopy.24

This advanced technique made it possible to overcome the limit of resolution encountered by regular confocal microscopy. However, superresolution microscopy is still not commonly used. The other imaging technique for HIV-1 in the nuclei of infected cells, HIV-IN-EGFP, was reported by Albanese et al.3 This system, which exploits the Vpr transincorporation approach to introduce integrase fused to EGFP, made it possible to obtain nuclear localization results that could not be reported by other methods of investigation. However, as reported by others, the transincorporation approach with wild-type integrase (Vpr-IN) generates low infectious viral particles. In an attempt to circumvent the limited infectivity we have modified the IN incorporated in the fluorescent HIV-1 with mutations (E11K and K186E) that were reported to improve infectivity in transcomplemented viruses.15 The newly generated fluorescent viruses showed an improved infectivity that was consistent with the results of Hare et al.15 HIV-1 fluorescent complexes are smaller and less intense. In our experimental setup, HIV-1 complexes were visible in the cytoplasmic compartment while complexes in the nuclear compartment could be detected only after introduction of a brighter fluorophore (superfolder GFP).22

The differential detection properties of cytoplasmic versus nuclear HIV-1 complexes were quantified and were consistent with a previous report24; we observed smaller and less bright fluorescent spots within the nuclear volume (Supplementary Fig. S5). As suggested by Lelek et al.,24 the differential size might be explained by the presence in the cytoplasm of particles that still have to go through Capsid uncoating.

The HIV-IN-EGFP system offers a direct approach to assess viral nuclear import, as an alternative to the indirect method using 2-LTR circles quantification,25 which is the reason behind numerous controversial results reported in the recent literature.26,27 Conversely, the power of the HIV-IN-EGFP method is supported by studies demonstrating that the effect of factors or drugs affecting nuclear import can be directly visualized in infected cells.9,10 This study further supports the advantages offered by simultaneous detection of nuclear and cytoplasmic viral complexes through IN-EGFP-labeled viruses: viral complexes are rarely detected in both compartments of TRIMCyp cells, while the same cells treated with a proteasome inhibitor, MG132, show an accumulation of viral complexes specifically at the cytoplasmic and perinuclear level. These observations were formerly reported by others through indirect experimental approaches20,21; the HIV-IN-EGFP system provides direct proof in support of the model suggesting a two-step TRIMCyp restriction involving proteasomes.20,21,28

This study reports other validating experiments of the IN-EGFP imaging system including the analysis of fluorescent EV, which in the absence of the viral genome did not show significant EGFP signals in the nuclear compartment. Interestingly, the low percentage of EV detected in the nuclear compartment may suggest that nuclear import either occurs during mitosis or does not strictly depend on genomic signals and that reverse transcription might not be an absolute requirement for nuclear import.29,30,31 Finally, we prove that the number of HIV-1 complexes detected in the nuclei of infected cells correlates with the titer of viral supernatants used for infection, thus further supporting the intact virological nature of the HIV-IN-EGFP system.

Overall, this study provides further data in support of the HIV-1 imaging approach based on IN-EGFP viral incorporation as a unique tool to assess viral events occurring between the cytoplasm and the nuclear volume.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jeremy Luban and Massimo Pizzato for providing the TRIMCyp and TRIMCyp-H126Q expressing cells. They also thank Sheref Mansy and José Manuel Paredes for valuable discussions. This work was supported by grants from the EU FP7 (THINC, Health-2008-201032), by the ISS Italian AIDS Program (Grant 40H90), and by the Provincia Autonoma di Trento (COFUND project, Team 2009–Incoming).

A.C., D.A., and A.C.F. conceived and designed the experiments. A.C. and A.C.F. wrote the paper. A.C.F., A.B., C.D., V.Q., and P.V. performed the experiments. F.D. and G.G. developed the PICs manager. A.C.F., A.B., and D.A. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.McDonald D, Vodicka MA, Lucero G, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG, Emerman M, and Hope TJ: Visualization of the intracellular behavior of HIV in living cells. J Cell Biol 2002;159:441–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arhel N, Genovesio A, Kim K-A, Miko S, Perret E, Olivo-Marin J-C, Shorte S, and Charneau P: Quantitative four-dimensional tracking of cytoplasmic and nuclear HIV-1 complexes. Nat Methods 2006;3:817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albanese A, Arosio D, Terreni M, and Cereseto A: HIV-1 pre-integration complexes selectively target decondensed chromatin in the nuclear periphery. PloS One 2008;3:e2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jouvenet N, Neil SJD, Bess C, Johnson MC, Virgen CA, Simon SM, and Bieniasz PD: Plasma membrane is the site of productive HIV-1 particle assembly. PLoS Biol 2006;4:e435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markosyan RM, Cohen FS, and Melikyan GB: Time-resolved imaging of HIV-1 Env-mediated lipid and content mixing between a single virion and cell membrane. Mol Biol Cell 2005;16:5502–5513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale BM, McNerney GP, Hubner W, Huser TR, and Chen BK: Tracking and quantitation of fluorescent HIV during cell-cell transmission. Methods 2011;53:20–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell EM, Perez O, Anderson JL, and Hope TJ: Visualization of a proteasome-independent intermediate during restriction of HIV-1 by rhesus TRIM5α. J Cell Biol 2008;180:549–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hübner W, Chen P, Del Portillo A, Liu Y, Gordon RE, and Chen BK: Sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag localization and oligomerization monitored with live confocal imaging of a replication-competent, fluorescently tagged HIV-1. J Virol 2007;81:12596–12607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christ F, Thys W, De Rijck J, Gijsbers R, Albanese A, Arosio D, Emiliani S, Rain J-C, Benarous R, Cereseto A, and Debyser Z: Transportin-SR2 imports HIV into the nucleus. Curr Biol CB 2008;18:1192–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desimmie BA, Schrijvers R, Demeulemeester J, Borrenberghs D, Weydert C, Thys W, Vets S, Van Remoortel B, Hofkens J, De Rijck J, Hendrix J, Bannert N, Gijsbers R, Christ F, and Debyser Z: LEDGINs inhibit late stage HIV-1 replication by modulating integrase multimerization in the virions. Retrovirology 2013;10:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu R, Limon A, Devroe E, Silver PA, Cherepanov P, and Engelman A: Class II integrase mutants with changes in putative nuclear localization signals are primarily blocked at a postnuclear entry step of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 2004;78:12735–12746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu R, Limón A, Ghory HZ, and Engelman A: Genetic analyses of DNA-binding mutants in the catalytic core domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol 2005;79:2493–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu R, Ghory HZ, and Engelman A: Genetic analyses of conserved residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol 2005;79:10356–10368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu R, Vandegraaff N, Cherepanov P, and Engelman A: Lys-34, dispensable for integrase catalysis, is required for preintegration complex function and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 2005;79:12584–12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hare S, Di Nunzio F, Labeja A, Wang J, Engelman A, and Cherepanov P: Structural basis for functional tetramerization of lentiviral integrase. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Primio C, Quercioli V, Allouch A, Gijsbers R, Christ F, Debyser Z, Arosio D, and Cereseto A: Single-cell imaging of HIV-1 provirus (SCIP). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:5636–5641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizzato M, Erlwein O, Bonsall D, Kaye S, Muir D, and McClure MO: A one-step SYBR Green I-based product-enhanced reverse transcriptase assay for the quantitation of retroviruses in cell culture supernatants. J Virol Methods 2009;156:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, and Luban J: Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature 2004;430:569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neagu MR, Ziegler P, Pertel T, Strambio-De-Castillia C, Grütter C, Martinetti G, Mazzucchelli L, Grütter M, Manz MG, and Luban J: Potent inhibition of HIV-1 by TRIM5-cyclophilin fusion proteins engineered from human components. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3035–3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Anderson JL, Campbell EM, Joseph AM, and Hope TJ: Proteasome inhibitors uncouple rhesus TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 reverse transcription and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:7465–7470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson JL, Campbell EM, Wu X, Vandegraaff N, Engelman A, and Hope TJ: Proteasome inhibition reveals that a functional preintegration complex intermediate can be generated during restriction by diverse TRIM5 proteins. J Virol 2006;80:9754–9760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pédelacq J-D, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, and Waldo GS: Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 2006;24:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lusic M, Marini B, Ali H, Lucic B, Luzzati R, and Giacca M: Proximity to PML nuclear bodies regulates HIV-1 latency in CD4+ T cells. Cell Host Microbe 2013;13:665–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lelek M, Di Nunzio F, Henriques R, Charneau P, Arhel N, and Zimmer C: Superresolution imaging of HIV in infected cells with FlAsH-PALM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:8564–8569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler SL, Hansen MS, and Bushman FD: A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat Med 2001;7:631–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Iaco A, Santoni F, Vannier A, Guipponi M, Antonarakis S, and Luban J: TNPO3 protects HIV-1 replication from CPSF6-mediated capsid stabilization in the host cell cytoplasm. Retrovirology 2013;10:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munir S, Thierry S, Subra F, Deprez E, and Delelis O: Quantitative analysis of the time-course of viral DNA forms during the HIV-1 life cycle. Retrovirology 2013;10:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yap MW, Dodding MP, and Stoye JP: Trim-Cyclophilin A fusion proteins can restrict human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection at two distinct phases in the viral life cycle. J Virol 2006;80:4061–4067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iordanskiy S, Berro R, Altieri M, Kashanchi F, and Bukrinsky M: Intracytoplasmic maturation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription complexes determines their capacity to integrate into chromatin. Retrovirology 2006;3:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaitseva L, Cherepanov P, Leyens L, Wilson SJ, Rasaiyaah J, and Fassati A: HIV-1 exploits importin 7 to maximize nuclear import of its DNA genome. Retrovirology 2009;6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdick RC, Hu W-S, and Pathak VK: Nuclear import of APOBEC3F-labeled HIV-1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:E4780–4789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.