Anemia in the elderly (defined as people aged > 65 years) is common and increasing as the population ages. In older patients, anemia of any degree contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality and has a significant effect on the quality of life. Despite its clinical importance, anemia in the elderly is under-recognized and evidence-based guidelines on its management are lacking.

Part of the problem here relates to its definition, which is based on WHO-criteria established in 1968.1 The WHO definition of anemia is hemoglobin (Hb) less than 130 g/L in men, Hb less than 120 g/L in non-pregnant women, and less than 110 g/L in pregnant women. Hemoglobin levels decline with age, and there has been a debate as to whether these values are applicable to older people, although there is no accepted alternative definition of anemia in this age group. Most clinicians, however, accept this definition and are of the opinion that the normal hemoglobin range should not be lowered for older people because of its association with morbidity, mortality and hospitalization. The challenge of defining a normal hemoglobin range lies in part in finding a cohort of ‘healthy’ elderly subjects confounded by the high prevalence of comorbidities and impairments in parallel with advancing age. In the analysis of Cheng et al.,2 an important proportion (60%) of the older adults were excluded due to frequent diseases including obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes, recent treatment for anemia, or recent surgery or hospitalization. Thus, the introduction of selection bias limits the practical applicability of this approach. Another approach is based on the definition of Hb concentrations that are optimal for the clinical outcome of elderly subjects. Based on the distribution of Hb levels, the elderly can be grouped into quartiles or quintiles, revealing inverse J-shaped correlations with unfavorable outcome. An increased mortality was found in the lower quintile (<137 g/L for men; <126 g/L for women) as defined in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort.3 Similarly, anemia correlated with increased hospitalization4 and mortality.4,5 Thus, a suggested optimal Hb value to avoid hospitalization and mortality was 130–150 g/L for women and 140–170 g/L for men, suggesting a redefinition of cut-off points for anemia.

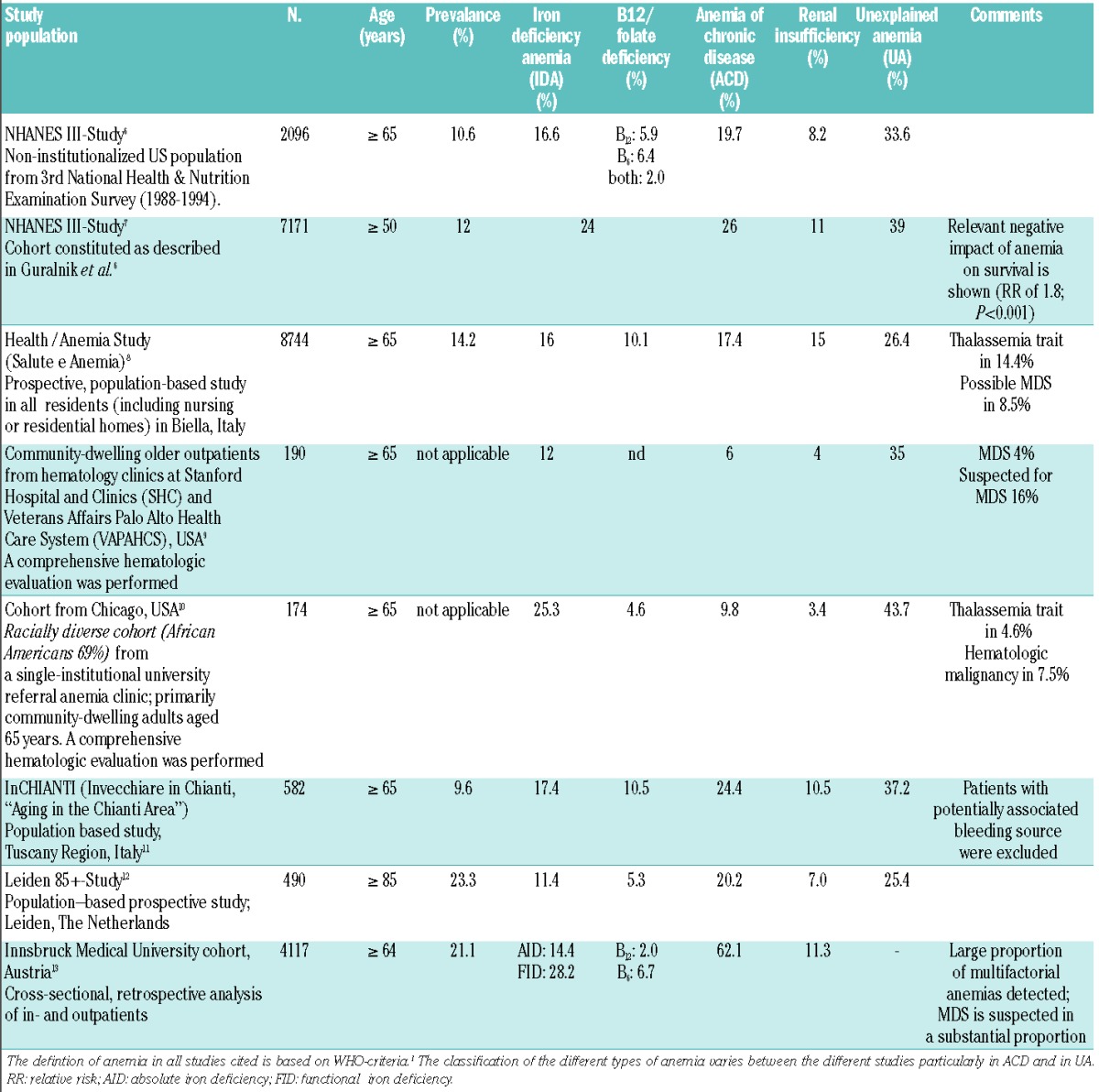

Nonetheless, based on the WHO definition, studies have estimated that, in people over 65 years, the prevalence of anemia is 12% in those living in the community, 40% in those admitted to the hospital, and as high as 47% in nursing home residents. All in all, an estimated 17% of those over 65 has been found to be anemic (Table 1).6–14 Based on this proportion, the current number of anemic elderly persons in the European Union is estimated to be as many as 15 million. This number is likely to increase dramatically in the coming years due to an aging population in Western societies.8,13

Table 1.

Prevalence and subtypes of anemia in the elderly in selected studies.

Anemia in the elderly is particularly relevant as it has a number of serious consequences. Anemia has been associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease,4 cognitive impairment,15 decreased physical performance and quality of life,16–18 and increased risk of falls and fractures.16 Furthermore, presence of anemia is significantly associated with longer hospital stays4,19 and with an increased risk of mortality, in particular, mortality related to cardiovascular disease.4 More importantly, anemia might be an early sign of a previously undiagnosed malignant disease.20

Causes of anemia in the elderly are divided into three broad groups: nutritional deficiency, anemia of chronic disease (ACD) and unexplained anemia (UA). These groups are not, however, mutually exclusive. In any given patient, several causes may co-exist and may each contribute independently to the anemia. Nutritional deficiencies represent a treatable subgroup and include lack of iron, vitamin B12 or folate. The most frequent nutritional anemia is due to iron deficiency, which is characterized by low serum ferritin levels and transferrin saturation (Table 1). However, normal/high serum ferritin levels do not rule out iron deficiency, as ferritin represents an acute phase protein, which might be elevated in inflammatory processes and with advanced age. Thus, the diagnosis should be mainly based on decreased transferrin saturation. Diagnosis of iron deficiency should not be an end in itself but should rather be the initiation of a search for its cause, including looking for a possible site of blood loss and for possible underlying malignancy. The pathophysiology of ACD is multifactorial and relates to a reduced efficiency of iron recycling from red blood cells resulting in a functional iron deficiency. There is enhanced apoptosis of erythroid progenitor cells in the marrow, an inadequate production of erythropoietin (EPO) and impaired response to EPO. It has been proposed that elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) underlie ACD and a key mediator is the induction of hepcidin synthesis by IL-6. Hepcidin inhibits iron absorption in the intestine and the release of recycled iron from the macrophages, resulting in an iron-restrictive anemia (reviewed by Weiss and Goodnough21). Unexplained anemia (UA) accounts for approximately one-third of all anemias in the elderly and represents primarily a diagnosis of exclusion, unclassifiable by currently available methods. The pathophysiology is complex and poorly understood. Although undiagnosed malignancy including myelodysplasia,13 previously unrecognized chronic kidney disease, and other uncommon causes may explain a proportion of the UAs, their combined contribution is relatively small. In populations where thalassemia is prevalent, thalassemia trait may account for another proportion of the UAs.8,10 Dissecting the causes of UA is confounded by the high frequency of co-morbidities in the elderly, age-associated increases in levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 that may reduce sensitivity of stem cells and progenitors to growth factors and induce hepcidin synthesis in an environment of reduced pluripotent hemopoietic stem cell reserve. Elevated hepcidin levels have been detected in UA, suggesting that inflammatory processes might contribute to anemia in the elderly, involving mechanisms similar to those encountered in ACD.12 Thus, a cause for a large proportion of the UAs remains unclear despite comprehensive hematologic evaluation (Table 1).9,10

Our great challenge now is to refine the pathological classification of anemia based on the integration of currently routinely available parameters, e.g. ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT), reticulocyte hemoglobin content (CHr), pre-inflammation markers and new parameters including plasma hepcidin, erythroferron and soluble hemojuvelin. This should lead to a better understanding of its pathophysiology and the role of hepcidin-targeted therapeutics.

Considering the central role of hepcidin in the pathophysiology of anemia in the elderly, it is not surprising that a plethora of drugs manipulating the hepcidin pathway for therapeutic purposes have been developed22 with some of these agents already being applied in clinical studies.

It is envisaged that a combination of these biochemical and genetic tests could refine classification of anemia in the elderly, leading to the development of individualized treatment algorithms that would facilitate the appropriation of therapeutic options, including ESAs with a target Hb 100–120 g/L, intravenous iron and novel oral iron formulations, as well as drugs directed at hepcidin or ferroportin.22 Blood transfusions should be kept to a minimum.

Anemia of the elderly represents a challenge and a burden for the individual, the community and health care providers. All healthcare providers, including hematologists, should be aware that anemia impacts a significant group within our societies. It is an entity that lies within our ability to diagnose and treat.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claire Steward for help in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial and other disclosures provided by the author using the ICMJE (www.icmje.org) Uniform Format for Disclosure of Competing Interests are available with the full text of this paper at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Blanc B, Finch CA, Hallberg L, Lawkowicz W, Layrisse M, Mollin DL, et al. Nutritional Anaemias. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization, Technical Report Series Geneva: World Health Organization, 1968:40 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CK, Chan J, Cembrowski GS, van Assendelft OW. Complete blood count reference interval diagrams derived from NHANES III: stratification by age, sex, and race. Lab Hematol. 2004;10(1):42–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakai NA, Katz R, Hirsch C, Shlipak MG, Chaves PHM, Newman AB, et al. A Prospective Study of Anemia Status, Hemoglobin Concentration, and Mortality in an Elderly Cohort: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2214–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn BR. Impact of anemia on hospitalization and mortality in older adults. Blood. 2006;107(10):3841–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Houwelingen AH, den Elzen WP, Mooijaart SP, Heijmans M, Blom JW, de Craen AJ, et al. Predictive value of a profile of routine blood measurements on mortality in older persons in the general population: the Leiden 85-plus Study. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e58050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shavelle RM, MacKenzie R, Paculdo DR. Anemia and mortality in older persons: does the type of anemia affect survival¿ Int J Hem. 2012:95(3):248–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tettamanti M, Lucca U, Gandini F, Recchia A, Mosconi P, Apolone G, et al. Prevalence, incidence and types of mild anemia in the elderly: the “Health and Anemia” population-based study. Haematologica. 2010;95(11):1849–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price EA, Mehra R, Holmes TH, Schrier SL. Anemia in older persons: etiology and evaluation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;46(2):159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artz AS, Thirman MJ. Unexplained anemia predominates despite an intensive evaluation in a racially diverse cohort of older adults from a referral anemia clinic. J Gerontol. 2011;66(8):925–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrucci L, Semba RD, Guralnik JM, Ershler WB, Bandinelli S, Patel KV, et al. Proinflammatory state, hepcidin, and anemia in older persons. Blood. 2010;115(18):3810–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Elzen WP, de Craen AJ, Wiegerinck ET, Westendorp RG, Swinkels DW, Gussekloo J. Plasma hepcidin levels and anemia in old age. The Leiden 85-Plus Study. Haematologica. 2013;98(3):448–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach V, Schruckmayer G, Sam I, Kemmler G, Stauder R. Prevalence and possible causes of anemia in the elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of a large European university hospital cohort. Clin Interv Aging 2014:9 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaskell H, Derry S, Andrew Moore R, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of anaemia in older persons: systematic review. BMC Geriatrics. 2008;8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denny SD, Kuchibhatla MN, Cohen HJ. Impact of anemia on mortality, cognition, and function in community-dwelling elderly. Am J Med. 2006;119(4):327–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beghe C, Wilson A, Ershler WB. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(Suppl 7A):3S–10S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Elzen WP, Willems JM, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J. Effect of anemia and comorbidity on functional status and mortality in old age: results from the Leiden 85-plus Study. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181(3–4):151–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penninx BW, Pahor M, Cesari M, Corsi AM, Woodman RC, Bandinelli S, et al. Anemia is associated with disability and decreased physical performance and muscle strength in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):719–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penninx BW, Pahor M, Woodman RC, Guralnik JM. Anemia in old age is associated with increased mortality and hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(5):474–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgren G, Bagnardi V, Bellocco R, Hjalgrim H, Rostgaard K, Melbye M, et al. Pattern of declining hemoglobin concentration before cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(6):1429–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):1011–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung E, Nemeth E. Manipulation of the hepcidin pathway for therapeutic purposes. Haematologica. 2013;98(11):1667–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]