Abstract

Objective

To determine whether state policies that regulate beverages in schools are associated with reduced in-school access and purchase of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and reduced consumption of SSBs (in and out of school) among adolescents.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

Public schools in 40 states.

Participants

Students sampled in fifth and eighth grades (spring 2004 and 2007, respectively).

Main Exposures

State policies that ban all SSBs and state policies that ban only soda for 2006-2007.

Main Outcome Measures

In-school SSB access, in-school SSB purchasing behavior, and overall SSB consumption (in and out of school) in eighth grade.

Results

The proportions of eighth-grade students who reported in-school SSB access and purchasing were similar in states that banned only soda (66.6% and 28.9%, respectively) compared with states with no beverage policy (66.6% and 26.0%, respectively). In states that banned all SSBs, fewer students reported in-school SSB access (prevalence difference, −14.9; 95% CI, −23.6 to −6.1) or purchasing (−7.3; −11.0 to −3.5), adjusted for race/ethnicity, poverty status, locale, state obesity prevalence, and state clustering. Results were similar among students who reported access or purchasing SSBs in fifth grade compared with those who did not. Overall SSB consumption was not associated with state policy; in each policy category, approximately 85% of students reported consuming SSBs at least once in the past 7 days. Supplementary analyses indicated that overall consumption had only a modest association with in-school SSB access.

Conclusion

State policies that ban all SSBs in middle schools appear to reduce in-school access and purchasing of SSBs but do not reduce overall consumption.

In the past 25 years, sources of energy intake among youth have shifted toward greater consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), such as soda, sports drinks, and high-calorie fruit drinks.1-4 This shift has important public health implications given that SSB consumption has been associated with youth obesity and weight gain,5-7 which have several physical and psychosocial consequences.8,9 Consumption of SSBs encourages weight gain because individuals do not compensate for consumption of liquid carbohydrates by reducing other sources of calories.10,11 The large quantities of rapidly absorbable carbohydrates that flavor SSBs also increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, independent of weight gain.7,12 Furthermore, SSB consumption can pose health risks by displacing milk consumption,13,14 thereby reducing calcium intake, and increasing the risk of dental caries.15-17

Surveillance studies have demonstrated that SSBs are widely available in schools nationwide.18-21 Foods and beverages sold outside of federal school meal programs are not required to meet federal nutrition standards, and this led the American Academy of Pediatrics,22 US Department of Agriculture,23 American Dietetic Association,24 and policy-making organizations25,26 to call for federal, state, and local policies to improve the nutritional content of school foods and beverages. The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 required local education agencies that sponsor school meal and other child nutrition programs to establish nutrition guidelines for foods and beverages sold outside of school meal programs.27 More recently, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 requires the US Department of Agriculture to develop regulations governing competitive foods and beverages sold in schools.28 Many states have also passed laws to regulate competitive foods,29-31 and the American Beverage Association, American Heart Association, and Clinton Foundation collaborated to establish School Beverage Guidelines to improve the nutritional content of school beverages by the start of the 2009-2010 school year.32

The Institute of Medicine recommended that all SSBs be banned in schools,33 but many state competitive food policies have focused primarily on soda while allowing sports drinks, fruit drinks, and other SSBs.31,34 Sodas are the primary type of SSB consumed by adolescents; soda accounted for more calories than any other food or beverage group among 14- to 18-year-olds in 2005-2006.35 Other SSBs represent a growing health concern, however. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently published a statement discouraging youth consumption of energy and sports drinks, for example,36 because many youth perceive them to be a healthy alternative to soda37 despite the high levels of added sugar.

Research has suggested that when policies restrict only certain foods or beverages, schools and students will compensate by obtaining different low-nutrient foods and beverages. A study in Washington State found that, in the second year of the wellness policy requirement (2007-2008), only 17% of schools were selling soda on campus, but 72% were selling other SSBs.38 After California established nutrition standards for competitive foods, availability of soda in schools decreased substantially, but availability of sports drinks increased slightly.39 In Texas, a statewide Public School Nutrition Policy appeared to cause students to obtain different high-calorie foods from different sources (eg, home).40 Although each study reported reduced SSB exposure or improvements in dietary consumption, researchers concluded that policies must provide healthy alternatives in all settings in order to be effective.39,40

As described earlier, not all state policies targeting school beverages have been comprehensive because many allowed SSBs other than soda. To our knowledge, no study has examined whether states that restrict only soda are as effective in reducing SSB availability and consumption compared with states with more comprehensive policies. The objective of this study was to estimate the association between different types of state beverage policies and in-school SSB access and purchasing and overall SSB consumption (in and out of school).

METHODS

MEASURES

Policy Data

State policies governing the sale of soda and other SSBs in middle schools in 2006-2007 were compiled as part of the Bridging the Gap research program.41 For purposes of this study, state “policy” was defined to include codified state statutory and administrative (ie, regulatory) laws effective as of September 2006. Policies were obtained through keyword searches and reviews of the tables of contents and indices of state laws available by subscription to the Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis legal research databases. Policies were double-coded by 2 trained coders and verified against secondary source state law data to ensure complete collection and coding interpretation.34,42-45

States were classified as having (1) a policy limiting the availability of soda and other SSBs (eg, “Only milk, water, and 100% juice will be available in school”), (2) a policy prohibiting soda but no policy limiting the availability of other SSBs (eg, “Allowed beverages include milk, water, energy drinks, and electrolyte replacement beverages”), or (3) no policy limiting any type of SSB.

Student Data

Student data were obtained from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class. This cohort began as a nationally representative sample of kindergarten students in fall 1998 and was followed up over time, through 7 rounds of data collection. The analyses in this study were based on data from round 6 (fifth grade, spring 2004) and round 7 (eighth grade, spring 2007). The policy data were merged to the individual-level Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class data on the basis of state-level geocode identifiers obtained under special agreement. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The dependent variables of interest were in-school SSB access, in-school SSB purchasing, and overall SSB consumption (which included in- and out-of-school consumption). Each variable was measured using a questionnaire administered at school. Access was measured by asking students, “In your school, can kids buy soda pop, sports drinks, or fruit drinks that are not 100% fruit juice in the school?” Purchasing was measured by asking, “During the last week that you were in school, how many times did you buy soda pop, sports drinks, or fruit drinks at school?” Overall consumption was measured by asking, “During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink soda pop, sports drinks, or fruit drinks that are not 100% fruit juice?” Students were instructed to consider all settings (school, home, etc) when reporting consumption. For purchasing and consumption, there were 7 response categories ranging from “I did not purchase/drink any” to “4 or more times per day.” Categories were collapsed to create dichotomous measures of weekly purchasing/consumption (ie, ≥1 in the past 7 days) and daily purchasing/consumption (ie, ≥1 per day).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Among the 9170 public school students who were measured in fifth grade, 2270 were excluded from the analyses because they enrolled in a private school (n=130), moved to another state (n=150), were missing data on school type (n=230), or were lost to follow-up (n=1760), leaving a final sample of 6900. Among those excluded, the prevalence of in-school SSB purchasing and weekly SSB consumption in fifth grade was similar compared with the study sample. Those excluded were less likely to report in-school SSB access (P<.001) and more likely to report daily SSB consumption (P=.04) in fifth grade. Those excluded were also less likely to be non-Hispanic white (P<.001) and more likely to live in an urban area (P<.001) or be below the poverty line (P<.001).

General linear models, with an identity link, were used to estimate differences between state policy categories in the probability of eighth-grade students reporting the following: (1) in-school SSB access, (2) weekly in-school SSB purchase, (3) daily in-school SSB purchase, (4) weekly overall SSB consumption (in and out of school), and (5) daily overall SSB consumption. Eighth-grade measures were modeled because the state policies that were used applied to the 2006-2007 school year and were linked to eighth-grade data collected in spring 2007. Indicator variables were used to adjust for student race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic other), poverty status (whether annual household income was above the federal poverty level), and school locale (urban, suburban, township, or rural). Models also adjusted for state obesity prevalence (continuous), using data from the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System,46 and used a robust variance estimate to adjust for within-state correlation.47 All analyses were conducted with Stata, version 11 (Stata-Corp, College Station, Texas).48

In addition to modeling eighth-grade outcomes in the overall sample, we investigated whether state policies were associated with within-student changes in SSB access, purchasing, and consumption from fifth to eighth grade by repeating the models in 2 panels—students who did not report the outcome in question (eg, access) in fifth grade and those who did. Comparing results across panels enabled us to explore whether state policies may be more effective at primary prevention (eg, preventing adolescents from starting to consume SSBs over time) or secondary prevention (eg, encouraging them to cease consumption), although the temporal sequence of measures precludes us from concluding that policies were the cause of any changes.

The policies that we examined were designed to reduce SSB access at schools, on the rationale that reducing within-school access will reduce overall consumption. To test this rationale, a supplementary analysis was conducted in which we estimated the association between within-student changes in SSB access at school and overall SSB consumption, using a fixed-effect model to adjust for unmeasured, time-invariant characteristics.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics of the study sample are presented by state policy category in Table 1. States that banned all SSBs and states that had no beverage policies generally had similar sociodemographic characteristics, but states that banned only soda had different distributions of race/ethnicity, locale, and poverty status. In particular, states that banned soda had higher proportions of Hispanic students (33.0%), students below the poverty line (22.3%), and students in urban areas (48.7%), and lower proportions of white, non-Hispanic students (44.8%) and students in township or rural areas (4.2% and 10.1%, respectively).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample, by 2006-2007 State Policy Governing Beverages Sold in Middle Schools

| Variable | None | Ban Soda Only | Ban All SSBs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student | |||

| No. of students | 2890 | 2840 | 1170 |

| Female sex, % | 49.3 | 50.1 | 51.1 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 67.8 | 44.8 | 70.7 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.2 |

| Hispanic | 7.3 | 33.0 | 10.5 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 13.1 | 10.3 | 6.7 |

| Locale, % | |||

| Urban | 23.3 | 48.7 | 14.7 |

| Suburban | 31.6 | 37.0 | 46.1 |

| Township | 20.8 | 4.2 | 18.1 |

| Rural | 24.2 | 10.1 | 21.1 |

| Below poverty line, % | 16.3 | 22.3 | 16.3 |

| Parental educational level, % | |||

| Mother with college degree | 29.3 | 26.5 | 28.5 |

| Father with college degree | 32.0 | 29.1 | 35.3 |

| Annual household income, $, % | |||

| ≤25 000 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 18.5 |

| 25 001-50 000 | 28.7 | 31.1 | 24.4 |

| 50 001-75 000 | 21.0 | 17.5 | 18.2 |

| 75 001-100 000 | 16.6 | 14.1 | 17.5 |

| >100 000 | 17.0 | 16.5 | 21.5 |

| State | |||

| No. of states | 22 | 11 | 7 |

| Obesity prevalence, mean, % | 22.4 | 22.3 | 22.6 |

Abbreviation: SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

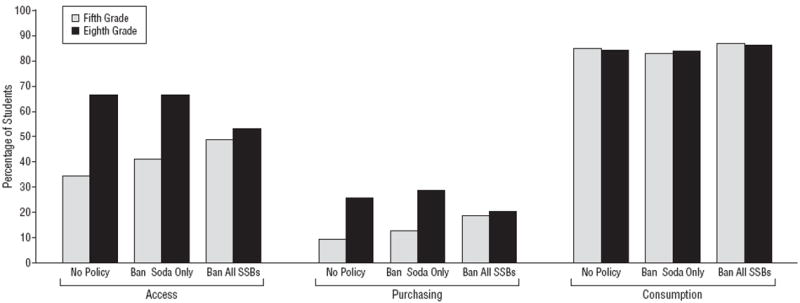

The Figure displays in-school SSB access, in-school SSB purchasing, and overall SSB consumption (in and out of school) in fifth and eighth grades, by state policy category. There were obvious differences between policy categories in patterns of SSB access and weekly purchase over time. States with no school beverage policy in 2006-2007 had, 3 years earlier, relatively low proportions of fifth-grade students who reported in-school SSB access and weekly purchase (34.7% and 9.7%, respectively). By 2007, however, the prevalence of SSB access and weekly purchase in these states had escalated to 66.6% and 26.0%, respectively. States that governed all SSBs in 2006-2007, in contrast, began with higher proportions of students who reported access and weekly purchase in fifth grade (48.9% and 19.0%, respectively) but experienced only a marginal increase over time (+4.5% and +1.4%, respectively). Overall SSB consumption (in and out of school) was similar across grades and policy categories. Most students (83%-87%) reported weekly consumption, and 26% to 33% reported daily consumption, regardless of grade or state policy.

Figure.

Prevalence of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) access within school, purchasing in school within the past week, and consumption anywhere within the past week, by state policy governing beverages sold in middle schools.

Table 2 presents the differences between policy categories in the adjusted prevalence of in-school SSB access and purchasing. Results are presented for each of the 3 panels—all students combined, those who reported the outcome in question in fifth grade, and those who did not. Across all models, SSB access and weekly purchase were equally prevalent in states that regulated only soda vs states with no beverage regulations. In states that regulated all SSBs, fewer students reported SSB access at school (prevalence difference, −14.9; 95% CI, −23.6 to −6.1) or weekly purchase of SSBs at school (−7.3; −11.0 to −3.5). The results were similar in all panels, although the effect size was stronger in students who reported access or purchase in fifth grade. There was no difference across policy categories in the proportion of students who reported daily SSB purchase (this outcome was not modeled in the right column because only 2.8% of students reported daily purchase in fifth grade).

Table 2.

Adjusted Differences Between State Policy Categories in the Prevalence of Within-School SSB Access and Purchasing Among Eighth-Grade Studentsa

| Outcome, by Policyb | Prevalence Difference (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Fifth Grade – Noc | Fifth Grade – Yesd | |

| SSB access | |||

| Ban soda | 0.3 (−7.1 to 7.6) | −1.7 (−10.5 to 7.0) | 1.6 (−6.3 to 9.5) |

| Ban all SSBs | −14.9 (−23.6 to −6.1)e | −10.9 (−20.2 to −1.5)f | −21.0 (−32.1 to −9.9)e |

| SSB weekly purchase | |||

| Ban soda | 1.3 (−3.6 to 6.2) | 0.2 (−4.7 to 5.1) | 7.4 (−2.9 to 17.8) |

| Ban all SSBs | −7.3 (−11.0 to −3.5)e | −6.4 (−10.3 to −2.6)e | −12.7 (−19.1 to −6.2)e |

| SSB daily purchase | |||

| Ban soda | 1.4 (−0.4 to 3.2) | 1.2 (−0.4 to 2.8) | NA |

| Ban all SSBs | −0.3 (−1.6 to 0.9) | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.0) | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, poverty status, locale, and state obesity prevalence.

Referent category is states with no beverage policy.

Restricted to participants who reported no in fifth grade (2004) for the outcome under study.

Restricted to participants who reported yes in fifth grade (2004) for the outcome under study.

P<.001.

P<.05.

In contrast to the results in Table 2, there were generally no differences between policy categories in overall (in and out of school) SSB consumption (Table 3). Daily SSB consumption was actually more prevalent in states that regulated SSBs in school (prevalence difference,5.8; 95% CI, 0.6 to 11.1), particularly among students who did not report daily consumption in fifth grade (7.7; 1.2 to 14.3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Differences Between State Policy Categories in the Prevalence of SSB Consumption Among Eighth-Grade Studentsa

| SSB Consumption, by Policyb | Prevalence Difference (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Fifth Grade – Noc | Fifth Grade – Yesd | |

| Weekly | |||

| Ban soda | −0.5 (−3.0 to 2.1) | −4.1 (−9.7 to 1.4) | 0.9 (−1.4 to 3.3) |

| Ban all SSBs | 2.0 (−0.5 to 4.5) | 2.3 (−8.5 to 13.1) | 1.7 (−0.7 to 4.1) |

| Daily | |||

| Ban soda | 2.3 (−1.4 to 6.0) | 2.5 (−1.5 to 6.6) | 2.8 (−2.1 to 7.8) |

| Ban all SSBs | 5.8 (0.6 to 11.1)e | 7.7 (1.2 to 14.3)e | 1.5 (−4.0 to 7.0) |

Abbreviation: SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, poverty status, locale, and state obesity prevalence.

Referent category is states with no beverage policy.

Restricted to participants who reported no in fifth grade (2004) for the outcome under study.

Restricted to participants who reported yes in fifth grade (2004) for the outcome under study.

P<.05.

The contrast between Tables 2 and 3 was reflected in the supplementary analysis in which we estimated the association between within-student changes in SSB access at school and overall SSB consumption. Results from the fixed-effect model (not shown) revealed that this association was, at best, statistically significant but small in magnitude. Changes in students’ SSB access at school were associated with 1.9% fewer students reporting weekly consumption (β=−0.02; 95% CI, −0.03 to −0.01), whereas the association with daily consumption was in the opposite direction (0.02; 0.00 to 0.04). In short, the prevalence of infrequent SSB consumption decreased slightly, whereas the prevalence of frequent SSB consumption increased slightly, when students’ access to SSB at schools was eliminated.

To summarize, state policies regulating beverages sold in middle schools were associated with reduced in-school SSB access and purchasing only if they banned all SSBs. Access and purchasing were equivalent in states that banned only soda compared with those with no policy at all. However, even comprehensive SSB policies were not associated with overall consumption of SSBs, which was largely independent of students’ in-school SSB access.

COMMENT

States and school districts nationwide have taken aggressive action to change the school food environment by providing foods and beverages of higher nutritional value.29-31,49 Our study adds to a growing body of literature that suggests that to be effective, school-based policy interventions must be comprehensive. States that only ban soda, while allowing other beverages with added caloric sweeteners, appear to be no more successful at reducing adolescents’ SSB access and purchasing within school than states that take no action at all. As students in this study progressed from fifth to eighth grade, their levels of SSB access and purchasing increased in states that ban soda as much as in states that have no SSB policy. States with more comprehensive laws banning all SSBs experienced only a slight increase in access and purchasing across grades.

The inability of soda-only bans to limit SSB access and purchasing raises questions about how schools comply with state policies. Woodward-Lopez et al39(p2142) reported that California legislation designed to improve the nutritional content of competitive foods and beverages had a positive effect on school food environments overall, but “many compliant foods were merely modified versions of highly processed foods that were previously non-compliant (eg, baked chips).” If schools adapt to state policies that ban soda by increasing the availability of sports drinks, fruit drinks, and other SSBs, the public health impact of these policies may be minimal. Even 100% fruit juice has caloric content similar to that of SSBs, and policies are unlikely to prevent excess weight gain if students replace SSBs with equal amounts of 100% fruit juice. If beverage policies are to improve student health, schools could do this by promoting unflavored water and limited servings of 100% fruit juice and low-fat milk, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine.33

The state policies that we examined were designed to change the school food environment to limit students’ access to SSBs while at school. Obviously, the rationale was that limiting students’ access to SSBs within school should reduce their overall consumption because they spend a large portion of their day in school during the school year. We found no evidence that state SSB policies were associated with lower overall consumption, however, and our supplementary analyses revealed that changes in students’ in-school SSB access reduced infrequent consumption (at least weekly) but slightly increased frequent consumption (at least daily), suggesting that heavier consumers compensated to a greater extent with increased consumption outside of school. Other studies similarly reported that schools were a relatively minor source of SSBs for adolescents3 and that the association between in-school SSB availability and SSB consumption was modest.38,50,51 In the contemporary “obesogenic” environment, youth have countless ways to obtain SSBs through convenience stores, fast-food restaurants, and other food outlets in their community.

These patterns have led some experts to question whether school-based policies will improve youth diet and reduce obesity.3,52,53 The development of time-series state-level policy databases will help to provide evidence on the extent to which such policies can reduce or prevent further increases in overall consumption. Nonetheless, our results based on a single cross section indicate that state policies produce positive changes in school food environments, but any effect on student dietary consumption may be modest without complementary changes in other sectors, including the food environment in the community, as well as at-home consumption.3,50,51,54 Experts have recommended broader policies, such as SSB taxes55 or regulations of food marketing aimed at children.56 Future research should explore the effect that school-based policies have on youth diet and weight gain when implemented in conjunction with policies in other sectors.

One of the strengths of this study was the ability to measure within-student changes in SSB access, purchasing, and consumption between fifth and eighth grade. Because the policies were compiled when the students were in eighth grade, though, it is impossible to conclude that policies preceded any changes in access or purchasing. Furthermore, students who were not followed up over time differed from the study sample in terms of socioeconomic characteristics, in-school SSB access, and overall SSB consumption, which may have biased results if students of low socioeconomic status benefit more or less from policies. The associations, or lack thereof, could also be biased by unmeasured confounding or measurement error, because youth commonly misreport their dietary intake.57 Finally, the student questionnaires did not separate different types of SSBs. This precluded us from examining whether the lack of association between soda-only policies and SSB access or purchasing is due to schools providing different types of SSBs or simply not complying with state policies.

In conclusion, comprehensive state policies that limit all SSBs within school appear effective in producing positive changes in school food environments. School is only one aspect of a child’s environment, though, and youth have proven to be very adept at compensating for individual changes to their environment. Any impact of state school-based SSB policies on youth dietary consumption may be modest without changes in other policy sectors.3,50,51,54

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Bridging the Gap program located within the Health Policy Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago (Dr Chaloupka) and by grant R01HL096664 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Dr Powell).

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or positions of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; or the National Institutes of Health.

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge Linda Schneider, Camille Gourdet, Kristen Ide, Amy Bruursema, and Steven Horvath, for their research support provided in compiling and analyzing the state-level policies; and Tamkeen Khan, for her research assistance with cleaning the individual-level Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class data.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Taber, Chriqui, and Powell had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. Study concept and design: Taber and Chriqui. Acquisition of data: Powell and Chaloupka. Analysis and interpretation of data: Taber, Chriqui, Powell, and Chaloupka. Drafting of the manuscript: Taber and Chriqui. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Taber, Chriqui, Powell, and Chaloupka. Statistical analysis: Taber and Powell. Obtained funding: Powell and Chaloupka. Administrative, technical, and material support: Chriqui and Chaloupka.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

References

- 1.Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):370–378. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1604–e1614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward-Lopez G, Kao J, Ritchie L. To what extent have sweetened beverages contributed to the obesity epidemic? Public Health Nutr. 2010;14(3):1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Youth. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(suppl 2):S2–S11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(6):794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattes RD. Dietary compensation by humans for supplemental energy provided as ethanol or carbohydrate in fluids. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(1):179–187. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despreés JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2477–2483. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavadini C, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. US adolescent food intake trends from 1965 to 1996. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(1):18–24. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lytle LA, Seifert S, Greenstein J, McGovern P. How do children’s eating patterns and food choices change over time? results from a cohort study. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(4):222–228. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller KE, Burt BA, Eklund SA. Sugared soda consumption and dental caries in the United States. J Dent Res. 2001;80(10):1949–1953. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn W, Burt BA, Sowers MR. Carbonated soft drinks and dental caries in the primary dentition. J Dent Res. 2006;85(3):262–266. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Marshall TA, et al. A longitudinal study of dental caries risk among very young low SES children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(2):116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston LD, Delva J, O’Malley PM. Soft drink availability, contracts, and revenues in American secondary schools. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4 suppl):S209–S225. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson N, Story M. Are ‘competitive foods’ sold at school making our children fat? Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):430–435. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):71–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner L, Chaloupka FJ. Wide availability of high-calorie beverages in US elementary schools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(3):223–228. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health. Soft drinks in schools. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1, pt 1):152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Department of Agriculture. Changing the scene: improving the school nutrition environment. [June 15, 2011]; http://www.teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/changing.html.

- 24.Pilant VB American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: local support for nutrition integrity in schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(1):122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanLandeghem K. Preventing Obesity in Youth Through School-Based Efforts. Washington, DC: National Governors Association, Center for Best Practices Health Policy Studies Division; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Association of State Boards of Education. [May 31, 2011];Fit, Healthy, and Ready to Learn: A School Health Policy Guide. http://nasbe.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=396:fit-healthy-and-ready-to-learn-a-school-health-policy-guide&catid=53:shs-resources&Itemid=372.

- 27.Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. 2004 Publ L No. 108-265 Section 204. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. 2010 Publ L 111-296, 204. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boehmer TK, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Dreisinger ML. Patterns of childhood obesity prevention legislation in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America’s Future, 2010. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker E, Chriqui JF, Chiang RJ. Obesity Prevention Policies for Middle and High Schools: Are We Doing Enough? Arlington, VA: National Association of State Boards of Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alliance for a Healthier Generation. Competitive beverage guidelines. [February 7, 2011]; http://www.healthiergeneration.org/companies.aspx?id=1376.

- 33.Institute of Medicine. Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Center for Science in the Public Interest. State school foods report card 2007. [October 17, 2010]; http://www.cspinet.org/2007schoolreport.pdf.

- 35.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: are they appropriate? Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1182–1189. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranjit N, Evans MH, Byrd-Williams C, Evans AE, Hoelscher DM. Dietary and activity correlates of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e754–e761. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson DB, Bruemmer B, Lund AE, Evens CC, Mar CM. Impact of school district sugar-sweetened beverage policies on student beverage exposure and consumption in middle schools. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3 suppl):S30–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward-Lopez G, Gosliner W, Samuels SE, Craypo L, Kao J, Crawford PB. Lessons learned from evaluations of California’s statewide school nutrition standards. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2137–2145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.193490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cullen KW, Watson K, Zakeri I. Improvements in middle school student dietary intake after implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):111–117. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaloupka FJ, Johnston LD. Bridging the Gap: research informing practice and policy for healthy youth behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4 suppl):S147–S161. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies Are Failing America, 2006. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies Are Failing America, 2007. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Association of State Boards of Education. State school health policy database. [September 11, 2011]; http://nasbe.org/healthy_schools/hs/index.php.

- 45.National Conference of State Legislatures. Database for state legislation on health topics. [April 8, 2011]; http://www.ncsl.org/IssuesResearch/Health/tabid/160/Default.aspx.

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [May 31, 2011]; http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/

- 47.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chriqui J, Schneider L, Chaloupka F, et al. School District Wellness Policies: Evaluating Progress and Potential for Improving Children’s Health Three Years After the Federal Mandate: School Years 2006–07 2007–08 and 2008–09. Vol. 2. Chicago: Bridging the Gap, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blum JE, Davee AM, Beaudoin CM, Jenkins PL, Kaley LA, Wigand DA. Reduced availability of sugar-sweetened beverages and diet soda has a limited impact on beverage consumption patterns in Maine high school youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(6):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fletcher JM, Frisvold D, Tefft N. Taxing soft drinks and restricting access to vending machines to curb child obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(5):1059–1066. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finkelstein E, French S, Variyam JN, Haines PS. Pros and cons of proposed interventions to promote healthy eating. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3 suppl):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sturm R. Disparities in the food environment surrounding US middle and high schools. Public Health. 2008;122(7):681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vecchiarelli S, Takayanagi S, Neumann C. Students’ perceptions of the impact of nutrition policies on dietary behaviors. J Sch Health. 2006;76(10):525–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1599–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:211–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ. Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(2):279–293. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]