Abstract

The cause and pathogenesis of gastroschisis are uncertain. We report the autopsy and placental pathology of a stillbirth at 20 gestational weeks, in which gastroschisis was accompanied by destructive lesions in the cerebral cortex and brainstem, as well as cardiac calcification, consistent with ischemic injury during the 2nd trimester. An important potential underlying mechanism explaining the fetal abnormalities is the presence of infarcts in the placenta, indicative at this gestational age of maternal vascular underperfusion. The association of gastroschisis with ischemic lesions in the brain, heart, and placenta in this case supports the concept that gastroschisis, at least in some instances, may result from vascular event(s) causing disruption of the fetal abdominal wall and resulting in the extrusion of the abdominal organs, as well as hypoxic–ischemic brain and cardiac injury.

Keywords: atresia, development, encephaloclastic maternal vascular underperfusion, vascular disruption

INTRODUCTION

Gastroschisis is defined as an abdominal wall defect, usually to the right of the umbilicus, through which abdominal organs (usually small intestine) extrude, without being covered by any membrane [1]. This anomaly is in contrast to (1) omphalocele, defined as protrusion of abdominal contents into the base of the umbilical cord, with coverage of the contents by an intact or ruptured membrane, and (2) abdominal wall defects accompanied by thoracoschisis, limb reduction defects, and encephaloceles and/or facial clefts, referred to as “limb-body wall complex” [2]. Gastroschisis must also be distinguished from sequelae of amniotic band syndrome. Although the cause of gastroschisis is uncertain, several theories have been proposed, including a catastrophic vascular event leading to ischemia of the fetal abdominal wall and extrusion of the abdominal contents [3,4]. Gastroschisis in conjunction with a disruptive brain lesion is rare, but its combination may represent a “window” into the pathogenesis of the faulty abdominal wall development, because both implicate a vascular origin. Here we present the findings of a 20-week fetus with the unique constellation of gastroschisis, destructive brain lesions, myocardial calcification, and placental findings of maternal vascular underperfusion and infarcts, suggesting a sequence of events involving 1 or more vascular events and simultaneous or repetitive ischemia to the fetus and placenta.

CASE REPORT

Clinical history

An 18-year-old G2P0, Native American woman with a prior pregnancy loss at 13 weeks gestation had been under prenatal care since 6 gestational weeks. Ultrasonography at 17 3/7 weeks indicated relatively little motion for the gestational age; it also demonstrated gastroschisis, enlarged cerebral ventricles, abnormally positioned hands and feet, and hyperextension of the head. At 20 weeks, she was seen for report of decreased fetal movements. Ultrasonography revealed intrauterine fetal demise. The patient had no history of diabetes, hypertension, or preeclampsia. Specifically, her blood pressure never rose above 112/62 mL of mercury across 7 prenatal visits beginning at 6 gestational weeks. Her weight ranged from 149 to 153.3 pounds over the pregnancy. Her gestational use of ethanol or illicit substances or exposure to cigarette smoke has remained unknown.

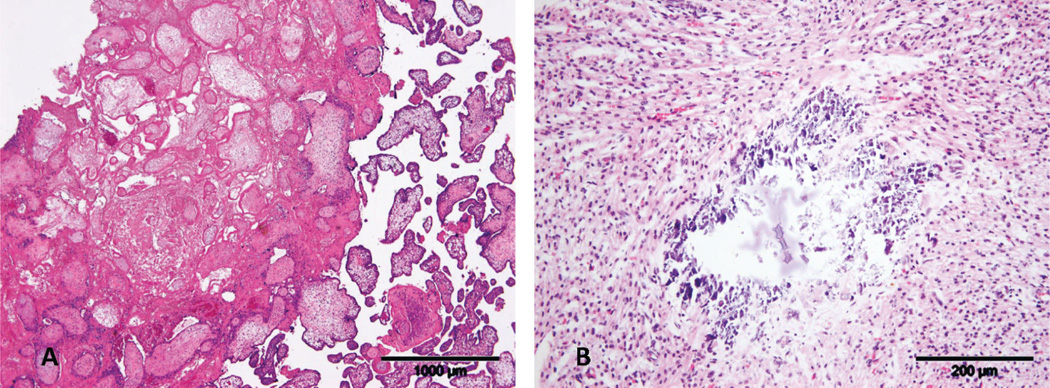

Placental examination

The placenta weighed 128 g (mean expected, 143 g; 25th percentile) [5] and had a 3-vessel umbilical cord. There was no evidence of amniotic disruption (ie, bands). Grossly, 5% of the placenta showed evidence of infarction. Microscopically, the infarction was present in several random microscopic sections and was due to maternal (spiral arteriolar) thrombosis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A. Central placental infarction secondary to spiral arteriolar thrombosis (not shown). Note accelerated maturation in surrounding chorionic villi. Scale bar = ×4. B. Remote dystrophic myocardial calcification secondary to ischemia. Scale bar = ×20. A color version of this figure is available online.

General autopsy findings

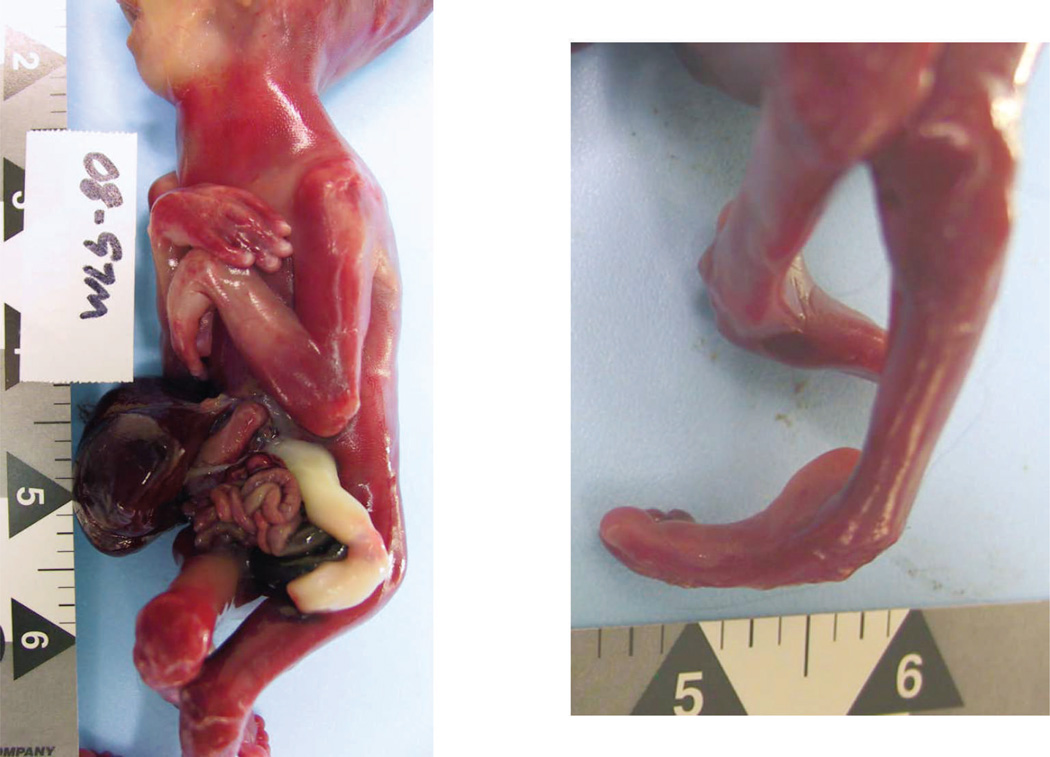

At autopsy, performed 3 days after delivery, the phenotypically female fetus had abnormal facies, including hypertelorism, low-set ears, and micrognathia, as well as arthrogryposis (multiple distal limb contractures) (Fig. 2). The fetus was growth-restricted, weighing 157 g (expected, 307±47 g), with a crown–heel length of 20 cm (expected, 24.4±1.8 cm) and head circumference of 14 cm (expected, 16.7±1.3 cm). The abdominal wall had a 1.2 cm defect, located superior to and to the right of the umbilicus, through which the small intestine and liver protruded; there was no covering membrane (Fig. 2). Microscopic examination of organs showed focal myocardial calcification, suggestive of remote ischemic injury (Fig. 1). The degree of maceration was limited (skin slippage) and suggested demise approximately 24 hours prior to delivery.

Figure 2.

General autopsy findings of the fetus. A. Lateral view of fetal trunk showing periumbilical abdominal wall defect and extruded abdominal viscera, as well as wrist and elbow contractures. B. Contractures of ankle. A color version of this figure is available online.

Neuropathologic findings

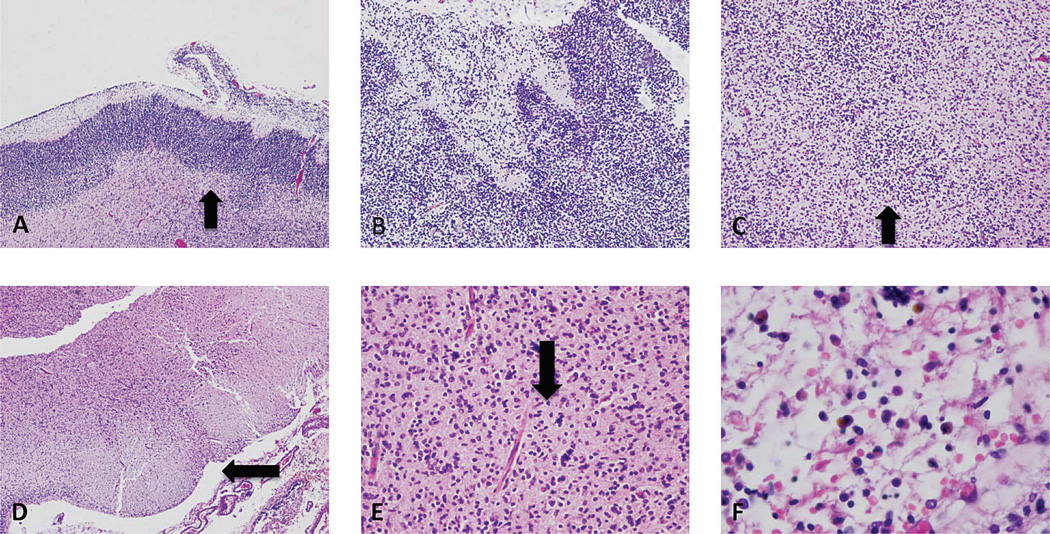

The brain weighed 20 g (expected, 45.5±7.2 g) and was macerated and fragmented, precluding optimal external examination. Microscopically, there was localized disruption of the cortical plate, with disorganization and focal mineralization of the immature brain tissue (Fig. 3). This disorganization was polymicrogyria-like on the cortical surface and nodular in deeper aspects of the cerebral mantle (Fig. 3). Adjacent, noninvolved cortex was consistent with 20 gestational weeks. The ventricular surface showed discontinuity (ie, focal ependymitis) (Fig. 3). There was no viral cytopathy or inflammation. In the rostral midbrain at the level of the oculomotor nucleus, there was focal necrosis, mineralization, and tissue loss in the reticular formation (cuneiformis and subcuneiformis) and unilateral scarring in the descending cortico-spinal tract (mid-portion of the cerebral peduncle) (Fig. 3). Basal nuclei, cerebellum, and other brainstem levels were not identified in the available tissue fragments.

Figure 3.

Neuropathologic findings. A. Segmental disruption of the cerebral cortical plate, with relatively preserved area on the left, and edge of disruption (arrow). B. High-power view of another area of segmental disruption of the cortical plate, with jumbled neuroblasts in the cortical plate extending up into Layer 1. C. A nodular collection of immature cells (arrow) in the intermediate zone (heterotopia). Midbrain section with linear scar in 1 cerebral peduncle (arrow) (D) and mineralization of nerve cells (arrow) (E). F. Leptomeninges containing iron-laden macrophages. A color version of this figure is available online.

Cytogenetics

Postmortem cytogenetic analysis of a skin sample revealed a normal 46,XX female karyotype.

DISCUSSION

This case is significant because it helps elucidate the pathogenesis of gastroschisis, a poorly understood congenital anomaly. The co-occurrence of gastroschisis and destructive (ischemic-type) brain lesions, in conjunction with placental ischemic lesions, suggests that the abdominal wall and brain lesions were due to vascular disruption(s) secondary to maternal vascular underperfusion and that the disruption(s) occurred at critical dual time points during abdominal and brain development. In addition, the finding of myocardial calcification further indicates systemic ischemia. Although the cause of the maternal vascular underperfusion in this case is unknown, we believe that our findings in the placenta are nevertheless valuable, because, together with the fetal findings in toto, they provide strong support for the vascular disruption hypothesis of gastroschisis [3] and add the novel insight that at least 1 etiologic mechanism may be maternal vascular underperfusion. In the following discussion, we highlight the findings in this case in the context of the current understanding of mechanisms of gastroschisis.

The prevalence of gastroschisis ranges from 0.5 to 4/10 000 births [2] and has been associated with young maternal age [3,6] (as in the present case); young maternal age is particularly highly represented among cases of isolated gastroschisis [2]. The proportion of cases associated with multiple congenital anomalies (ie, nonisolated gastroschisis) varies from 1.9% to 26.6%, depending on registry records in different geographic regions [2]. Related gastrointestinal anomalies include intestinal atresias and malrotation; nongastrointestinal abnormalies include cleft lip and palate, choanal atresia, and cardiopulmonary defects. None of these somatic abnormalities were found in the present case.

Brain anomalies have been reported in association with gastroschisis, and these include (1) neural tube defects, such as anencephaly, spina bifida, or encephalocele (5.3%); (2) microcephaly (0.1%); and (3) hydrocephalus (1.3%). Absence of the septum pellucidum was described on prenatal ultrasonography in 3 cases in the 3rd trimester. In that report, Case 2 had porencephaly, confirmed on fetal magnetic resonance imaging, indicative of an in utero destructive (ischemic) process prior to 33 weeks gestation, when the lesion was 1st detected. In a large epidemiologic study, a finding that the authors termed “reduction deformities” of the central nervous system, presumed to represent disruptive (ie, acquired) loss of brain tissue of possible vascular origin but not specifically defined or illustrated by them, were associated with gastroschisis only rarely (0.3%) [2] but, as discussed below, may reflect timing of proposed vascular insult(s).

Abdominal wall defect timing

As to the pathogenesis and timing of gastroschisis, a leading hypothesis includes vascular disruption of the abdominal wall [3]. In the embryonic period, the paired omphalomesenteric arteries connect the aorta with the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies the small intestines. The left omphalomesenteric artery is normally ablated, while the right continues to perfuse the omphalocele and its contents, along with the skin at the umbilicus, during and after the return of the intestines to the abdomen at 10 weeks gestation [3]. In the event of premature ablation of the left omphalomesenteric artery or disruption of perfusion of the right, local tissue necrosis ensues, and the organs remain outside the abdominal wall after 10 weeks.

Destructive brain lesion timing

Only a minority of gastroschisis cases have recognized ischemic brain lesions [2]. One report describes mono-chorionic–diamniotic gestation wherein fetal demise of 1 twin occurred between 13 and16 weeks and the liveborn co-twin’s gestation continued to term. The liveborn twin had segmental atrophy of brain structures in the distribution of the posterior cerebellar arteries [7]. In this case, polymicrogyria was noted at the edges of the atrophic brain region, as well as nodular heterotopic groups of immature cells (similar to those seen in our case), the latter attributed to disruption of neuronal migration from vascular effects related to the demised cotwin. The placenta in that case was not described as having any lesions [7]. In our case, the localized destruction of an otherwise appropriately developing cortical plate, with disorganization in the form of nodular heterotopias, is similar to that report. The timing of the brain injury in our case is most likely to have been prior to the ultrasonogram at 17 3/7 weeks, which already showed expanded ventricles and evidence of reduced fetal movement. This early-to-mid gestational period is known to be part of the epoch of active neuroblast migration in the cerebral hemispheres [8].

The brainstem injury found in this case shares features with those described in Moebius syndrome, defined clinically as 6th and 7th nerve palsies [8], which has been attributed likewise to vascular disruption early in gestation. Some authors also include evidence of the fetal akinesia sequence, ie, arthrogryposis, pulmonary hypoplasia, micrognathia, and high-arched palate [9], in Moebius syndrome, as seen in our case,. The neuropathology of Moebius syndrome includes tegmental necrosis, atrophy, and mineralization in the pons and medulla, including cranial nerve nuclei, as well as cerebellar foliar atrophy [9], olivary hypoplasia [10], and germinal matrix hemorrhage [10]. Although the medulla and pons were not available for review in our case, the destructive midbrain lesions were similar to those reported in Moebius syndrome. The involvement in our case of the corticospinal tract, noted unilaterally in 1 section, explains, at least in part the (bilateral) fixed joint contractures due to motor impairment and limited fetal movement. Of note, arthrogryposis is seen in 0.5% of cases of gastroschisis [2].

The type and timing of the injuries responsible for the Moebius syndrome are favored to be vascular disruption in the 6th to 7th week of gestation; this timing is much earlier than we would expect from the cortical disruptive changes in our case and strongly suggests that more than 1 hypoxic–ischemic episode is in play. The possibility of multiple vascular insults is also raised when one considers that the vast majority of gastroschisis cases survive gestation and can undergo successful surgical repair at birth. By contrast, as many as 10% of intrauterine demises of fetuses with gastroschisis have no other explanation of cause of death, suggesting that gastroschisis itself is sufficient [11]. Proposed mechanisms focus upon consequences secondary to gastroschisis that then result in demise, ie, compression of the umbilical cord by the extruded abdominal contents leading to fetal brain ischemia, or vagal effects from traction on the displaced mesentery and/or dilatation of the bowel segments, presumably causing decreased cerebral perfusion [12]. Evidence for fetal brain ischemia following the documented occurrence of gastroschisis is presented in a series of gastroschisis cases having undergone prenatal monitoring showing signs of fetal distress, with later fatal perinatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy, or cerebral palsy and/or neonatal seizures in survivors [11]. Thus, the abdominal wall and cerebral ischemic events may not occur simultaneously.

Placental perfusion timing

Placental abnormalities in gastroschisis are rarely reported in the literature. A large epidemiologic study of placental abnormalities associated with different types of body wall malformations found no association with abnormal umbilical vessel number and gastroschisis, and placental weight was on average larger in gastroschisis than in other types of cases; however, other details of placental pathology, including the incidence of maternal vascular underperfusion, were not provided [13]. Thus, the role of the placenta in the pathogenesis of gastroschisis has been inadequately investigated and highlights the importance of the present report in documenting maternal vascular underperfusion as a possible underlying cause of intermittent ischemia to the brain, myocardium, and possibly abdominal wall. Our vascular placental findings thus point out the utility of detailed placental examination in the study of fetal vascular disruption defects.

Maternal vascular underperfusion refers to chronically reduced uterine-to-placental blood flow. Placental infarction occurs when maternal uterine spiral arteriolar flow into the placenta is disrupted by thrombosis, vasoconstriction, or rupture (abruption), resulting in ischemic necrosis to the portion of the placenta served by the affected vessel. Although an occasional placental infarct is not uncommon later in pregnancy, placental infarction is always pathologic in mid-gestation. Additional consequences of chronic uteroplacental underperfusion include fetal and placental growth restriction, which were both present in this pregnancy. At this gestational age, the constellation of growth restriction and infarction indicates early-onset maternal underperfusion, conceivably beginning in the 1st trimester during abdominal wall closure and extending through periods of organ development.

Other factors

In considering further the pathogenesis of gastroschisis in our case, chromosomal syndromes such as trisomy 18, 13, or 21 or sex chromosome anomalies are found in a minority (1.2%) of cases [2], all disorders excluded by cytogenetic analysis in the present case. With regard to maternal toxic exposures, a meta-analysis of 172 articles (a total of 173 687 malformed cases and 11 674 332 unaffected controls) reported a statistically significant increased odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI 1.28–1.76) of gastroschisis in mothers who smoked during pregnancy [14]. If combined with maternal vasoactive drugs (pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, ephedrine, and methylenedioxymethamphetamine), the odds ratio (controlled for age, education, income, other drug use, and alcohol intake) for maternal smoking is 2.1 (95% CI 1.0–4.4) for gastroschisis, with the risk increased with increasing cigarette use [4]. Of note, nicotine and pseudoephedrine derivatives are well known for their vasoconstrictive effects [4]. Periconceptional alcohol consumption is also associated with an increased incidence of gastroschisis (OR = 1.40; CI: 1.17–1.67) [15]. Details of adverse prenatal exposures for our case are not available.

The finding of calcification of the myocardium further supports a hypoxic–ischemic mechanism of fetal injury, although the contribution of this to understanding the timing of events is limited.

In our case, we propose that the gastroschisis and destructive brain lesions, along with the myocardial calcification, occurred as a consequence of placental infarction accompanying maternal vascular underperfusion, the latter of unknown cause. It is likely in our case that more than 1 vascular event occurred over a periodand affected the formation of the abdominal wall at a time independent of the cerebral cortex, thereby resulting in the constellation of chronic ischemic-type changes detected at 20 weeks. This unique case dramatically illustrates the co-occurrence of lesions in separate organ systems that are ischemic (“disruptive”) in origin, occur after the embryonic period and before midgestation, and are considered secondary to vascular compromise in the placenta, thereby further supporting the vascular disruption hypothesis of gastroschisis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patient for her generosity and willingness to participate in the Safe Passage Study and also her clinical caretakers. We are grateful to the Oglala Sioux Tribe Research Review Board for their support of the study and this report.

References

- 1.Brunicardi F, Andersen D, Billiar T, Dunn D, Hunter J, Pollock, editors. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 8th ed. Chicago: McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 1493. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mastroiacovo P, Lisi A, Castilla EE, et al. Gastroschisis and associated defects: an international study. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:660–671. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyme HE, Higginbottom MC, Jones KL. The vascular pathogenesis of gastroschisis: intrauterine interruption of the omphalomesenteric artery. J Pediatr. 1981;98:228–231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Association of vasoconstrictive exposures with risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Epidemiology. 2003;14:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinar H, Sung CJ, Oyer CE, Singer DB. Reference values for singleton and twin placental weights. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1996;16:901–907. doi: 10.1080/15513819609168713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry CJ, Lammer EJ, Nelson V, Shaw GM. Schizencephaly: heterogeneous etiologies in a population of 4 million California births. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;137:181–189. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barth PG, van der Harten JJ. Parabiotic twin syndrome with topical isocortical disruption and gastroschisis. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;67:345–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00687825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman MG, editor. Congenital Malformations of the Brain: Pathologic, Embryologic, Clinical, Radiologic, and Genetic Aspects. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lammens M, Moerman P, Fryns JP, et al. Neuropathological findings in Moebius syndrome. Clin Genet. 1998;54:136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moya MP, Delong GR, Barboriak D, Cummings TJ. A lethal association of congenital apnea with brainstem tegmental necrosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burge DM, Ade-Ajayi N. Adverse outcome after prenatal diagnosis of gastroschisis: the role of fetal monitoring. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:441–444. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalache KD, Bierlich A, Hammer H, Bollmann R. Is unexplained third trimester intrauterine death of fetuses with gastroschisis caused by umbilical cord compression due to acute extra-abdominal bowel dilatation? Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:715–717. doi: 10.1002/pd.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Frias ML, Bermejo E, Rodriguez-Pinilla E. Body stalk defects, body wall defects, amniotic bands with and without body wall defects, and gastroschisis: comparative epidemiology. Am J Med Genet. 2000;92:13–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000501)92:1<13::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hackshaw A, Rodeck C, Boniface S. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:589–604. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson S, Browne ML, Rasmussen SA, et al. Associations between periconceptional alcohol consumption and craniosynostosis, omphalocele, and gastroschisis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:623–630. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]