Abstract

A metal-free, Lewis acid-promoted intramolecular aminocyanation of alkenes was developed. B(C6F5)3 activates N-sulfonyl cyanamides, leading an formal cleavage of the N-CN bonds in conjunction with vicinal addition of sulfonamide and nitrile groups across an alkene. This method enables atom-economical access to indolines and tetrahydroquinolines in excellent yields, and provides a complementary strategy for regioselective alkene difunctionalizations with sulfonamide and nitrile groups. Labeling experiments with 13C suggest a fully intramolecular cyclization pattern due to lack of label scrambling in double crossover experiments. Catalysis with Lewis acid is realized and the reaction can be conducted under air.

Keywords: Bond Activation, Lewis Acid, Mechanism, Aminocyanation, Alkene

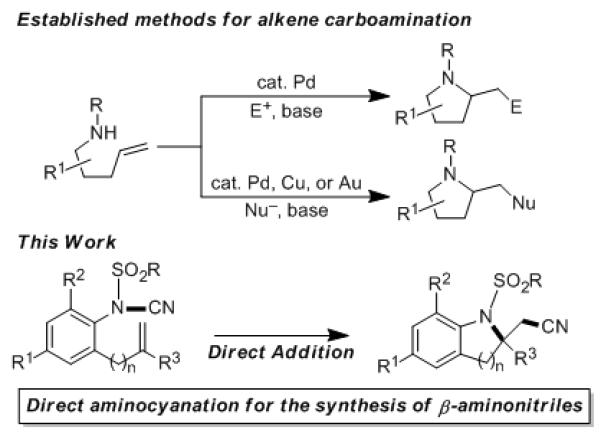

Alkene addition reactions are a hallmark of organic chemistry, yet significant problems remain unsolved.[1] Recent successes include forming new C-N bonds in conjunction with vicinal C-C,[2,3] C-O,[4] C-N,[5] C-H,[6] or C-X[7] bonds. These alkene aminofunctionalization reactions represent a unique strategy for the synthesis of valuable nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Despite significant developments, the established aminofunctionalization methods typically rely upon an exogenous electrophile (e.g., aryl halides) or nucleophile (e.g., halides, amines, carboxylates) to furnish the subsequent C-C or C-heteroatom bonds vicinal to the nitrogen (Scheme 1).[8] To our knowledge, a direct intramolecular addition approach to aminocyanation is unexplored.

Scheme 1.

Carboamination of Alkenes

Recently, our group[9] and Nakao’s group[10] independently reported two metal-catalyzed oxyfunctionalization reactions of alkenes through the activation of O-CO and O-CN bonds of esters and cyanates, respectively. Though this early work was pioneering, the corresponding chemistry to install nitrogen is potentially more powerful. Due to the versatile synthetic utility of the cyano group[11] and the persistent demand for methods to prepare functionalized nitriles,[12] we envisioned that the aminocyanation of alkenes (Scheme 1) would allow straightforward access to β-aminonitriles. These compounds are versatile precursors to the biologically and pharmacologically important β-amino acids.[13] To our surprise, the well-developed strategies for alkene aminofunctionalization[2-7] have only recently been applied in introducing cyano groups onto the alkene double bond. In 2013, Xiong, Li, Zhang, and co-workers reported the first example of alkene aminocyanation. Their work focused on aminocyanation of styrenes in an intermolecular context and was thought to proceed via a Cu-promoted radical addition pathway using TMS-CN as the cyanide source and N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide as the nitrogen source.[14]

Cyanamides (R1R2N-CN) are versatile one-carbon, two-nitrogen building blocks for heterocycle synthesis.[15] These bench-stable compounds are easily prepared by reaction of the corresponding secondary or tertiary amine with BrCN (von Braun reaction).[16] While most transformations of cyanamides occur at the cyano group, methods for cleaving the N-CN bond of cyanamides are rare, presumably due to the double bond character of N-CN bonds.[17] Owing to this challenge, catalytic cleavage of N-CN bonds has only recently been reported.[18,19] Notably, Falck and Wang reported a Rh-catalyzed, cyano-group transfer from an ortho cyanamide to an alkene of an alpha methyl styrene. They proposed metal mediated N-CN bond cleavage as a key step and the reaction required a relatively high catalyst loading (20 mol% of Rh).[19] This N-CN bond activation was conceptually in accordance with our early mechanistic thinking regarding alkene aminocyanation. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, intramolecular aminocyanation of alkenes – by any mechanism – has never been described. Here, we report a Lewis acid-promoted intramolecular aminocyanation of alkenes. We demonstrate the construction of 2,2-disubstituted indolines[20] and 2,2-disubstituted tetrahydroquinolines in an atom-economical fashion. The highlight of our approach is a novel mechanism for aminocyanation of alkenes via a non-degradative rupture at the N-CN bond.

Recently, N-cyano-N-phenyl-p-toluene sulfonamide (NCTS) has been employed as a bench-stable and less-toxic cyanation reagent in metal-catalyzed cross-coupling[21] and arene C-H cyanations,[22] implying a metal-mediated N-CN cleaving process. Meanwhile, Lewis acid co-catalysts, particularly BPh3, have proven effective at accelerating metal-catalyzed carbocyanation[23] and oxycyanation[10] of alkenes.

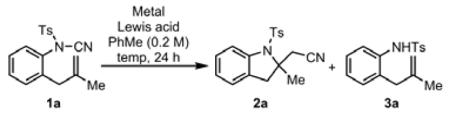

We attempted to take advantage of the electron-withdrawing tosyl group to weaken the N-CN bond of NCTS-type cyanamides while incorporating the activating effect of a Lewis acid on the cyano group. Therefore, we initiated our investigation of aminocyanation conditions by treating N-tosyl cyanamide 1a with a variety of transition metal and Lewis acid additives (see the Supporting Information for details on discovery and optimization). We quickly identified that the combination of rhodium (I) complexes and boron Lewis acids were effective (Table 1, entries 1-4). As Lewis acid strength increased from BPh3 to B(C6F5)3, the yield of 2a improved from 49 to 72% with minimal reductive de-cyanation by-product 3a observed in entry 2.[24] Also, the temperature required for acceptable conversion of 1a could be decreased, with 90 °C proving optimal (entries 2-4). Dramatically, a reaction employing B(C6F5)3 in the absence of added rhodium still gave 2a in a 90% yield (entry 5)! This observation prompted us to examine other Lewis acids to promote aminocyanation. Isoelectronic Lewis acids BF3*OEt2, AlCl3, and Me2AlCl each provided product 2a, albeit in lower yields than B(C6F5)3 (entries 6-8). Reaction of AgOTf or Cu(OTf)2 with 1a failed to produce detectable amounts of 2a, instead gave complex mixtures (entries 9-10). Zn(OTf)2 or Sc(OTf)3 were also ineffective, returning 1a without a detectable amount of 2a (entries 11-12). Reaction of 1a with SnCl4 provided 2a in 49% (entry 13), but also provided an insoluble black precipitate as a by-product. Interestingly, BPh3 was an ineffective promoter, even at 150 °C (entry 14).

Table 1.

Development of Aminocyanation Conditions

| Entry | Metala | Lewis acidb | Temp (°C) |

Yield of 2a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 | BPh3 (1.2 equiv) | 110 | 49c |

| 2 | [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 | B(C6F5)3 | 110 | 72d |

| 3 | [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 | B(C6F5)3 | 90 | 89d |

| 4 | [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 | B(C6F5)3 | 80 | 71d |

| 5 | - | B(C6F5)3 | 90 | 90d |

| 6 | - | BF3•OEt2 | 90 | 31d |

| 7 | - | AlCl3 | 90 | 52d |

| 8 | - | Me2AlCl | 90 | 11c |

| 9 | - | Ag(OSO2CF3) | 90 | -e |

| 10 | - | Cu(OSO2CF3)2 | 90 | -e |

| 11 | - | Zn(OSO2CF3)2 | 90 | -f |

| 12 | - | Sc(OSO2CF3)3 | 90 | -f |

| 13 | - | SnCl4 | 90 | 49c |

| 14 | - | BPh3 | 150 | -f |

5 mol% Rh complex used.

1.0 equiv of Lewis acid was used unless otherwise specified.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using p-methoxyacetophenone as the internal standard.

Yield after column chromatography.

No 2a detected by NMR, complex mixture formed.

No 2a detected by NMR, only 1a was detected.

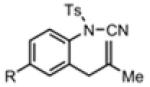

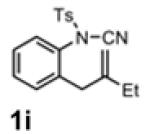

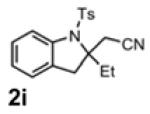

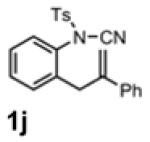

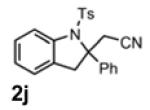

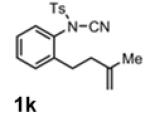

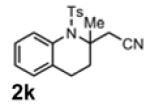

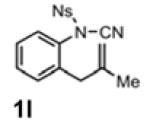

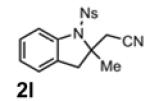

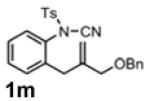

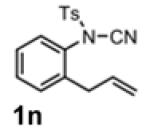

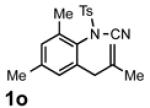

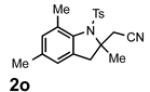

With the identification of suitable reaction conditions, the scope of Lewis acid-promoted intramolecular aminocyanation was investigated. Substrates bearing alkyl (Table 2, entries 1 and 2) or halo groups on the aromatic ring (entries 3-5) provided the corresponding indolines in excellent yields. It is worth noting that the presence of bromide para to the cyanamide moiety (entry 5) was well-tolerated, as this offers a convenient handle for further functionalization. The electronic effects of para-substituents on the aryl ring appeared to be inconsequential as substrates containing either electron-donating (R = Me, OMe, entries 1 and 7) or electron-withdrawing (R = F, CF3, entries 3 and 6) groups para to the cyanamide underwent the reaction in excellent yields (≥92%). Substitution at the alkene, either alkyl or phenyl, was tolerated and, in fact, necessary for the reaction. The ethyl- and phenyl-1,1-substituted alkenes (1i and 1j, entries 8 and 9) afforded the corresponding indolines in high yields; however, allyl substrate 1n returned only unconsumed starting material (entry 13). Substrates with internal alkenes (including trisubstituted) provided complex mixtures of products, alkene substitution remains a limitation at this time. Benzyloxymethyl-substituted alkene 1m also failed to provide product (entry 12), which was tentatively attributed to the inductive effect of the benzyloxy group (vide infra).[25] An extended alkene tether found in substrate 1k afforded the tetrahydroquinoline 2k in 93% yield (entry 10). Changing the protecting group at nitrogen from tosyl to nosyl in substrate 1l provided para-nosyl indoline 2l in almost quantitative yield (99%, entry 11). The relatively mild conditions for cleaving nosyl groups should allow convenient post-functionalization on the nitrogen atom.[26] Additionally, methyl substitution ortho to the cyanamide moiety (entry 14) was tolerated, giving indoline 2o in 90% yield.

Table 2.

Scope of Alkene Aminocyanationa

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 1 | 1b, R = Me | 2b | 92 |

| 2 | 1c, R = t−Bu | 2c | 92c |

| 3 | 1d, R = F | 2d | >99 |

| 4 | 1e, R = Cl | 2e | 95 |

| 5 | 1f, R = Br | 2f | 96 |

| 6 | 1g, R = CF3 | 2g | 94 |

| 7 | 1h, R = OMe | 2h | 99 |

| 8 |

|

|

>99 |

| 9 |

|

|

>99 |

| 10d |

|

|

93 |

| 11 |

|

|

99 |

| 12 |

|

– e | 0 |

| 13 |

|

– e | 0 |

| 14 |

|

|

90 |

Conditions: substrate (0.1 mmol), B(C6F5)3 (0.1 mmol), PhMe (0.5 mL), 90 °C, 24 h.

Yields after column chromatography.

Average of two runs.

Reaction time: 28 h.

Unconsumed starting material.

Ts = p-toluenesulfonyl, Ns = p-nitrobenzenesulfonyl.

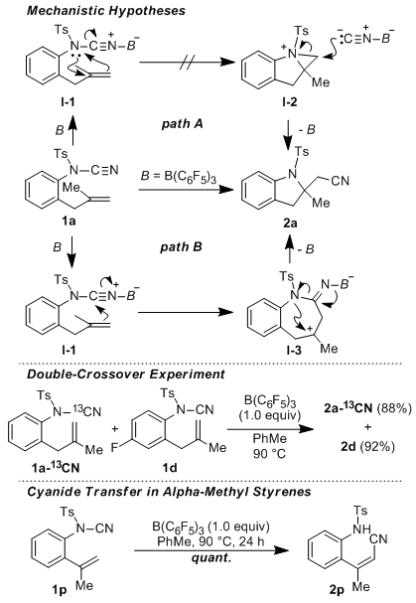

Based on the ability of B(C6F5)3 to promote intramolecular aminocyanation, we needed to revise our mechanistic thinking. Wang and coworkers recently reported that electrophilic cyanations of indoles[27] is accomplished using NCTS and a Lewis acid. This provides precedence for the nucleophilic cleavage of N-CN bonds and cyano group transfer under Lewis acid conditions. In aminocyanation, however, both groups are transferred to the alkene. We hypothesized that the NCN lone pair of cyanamide 1a initially coordinated to B(C6F5)3 affording adduct I-1 (Scheme 2).[28] This set the stage for an intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the alkene, but the mode of attack was unclear.

Scheme 2.

Mechanistic Experiments and Considerations

We considered a mechanism involving N-CN cleavage via aziridinium ion formation (path A, Scheme 2) and a non-fragmenting pathway involving nucleophilic attack of the alkene at the central cyanamide carbon (path B, Scheme 2). Aziridinium ion formation via B(C6F5)3-promoted loss of cyanide was attractive due to the remarkable “anion abstracting properties of this special boron compound”.[29, 30] The hypothesis involving nucleophilic attack of the alkene at the central cyanamide carbon was attractive since this is the typical site of nucleophile attack on cyanamides.[31] These hypotheses were tested by a double-crossover experiment (Scheme 2). A mixture of 1d and the 13C-labeled cyanamide 1a (1a-13CN) afforded only the non-crossover products 2d and 2a-13CN. The lack of crossover in the experiment indicated that alkene aminocyanation proceeds in a fashion that is inconsistent with the aziridinium ion hypothesis (Path A).[32]

The crossover experiments ruled out path A. We note that the success of cyanamides bearing more nucleophilic alkenes (such as 1i and 1j) and the failure of cyanamides bearing less nucleophilic alkenes (1m and 1n) is consistent with rate-limiting alkene attack. The mechanism by which intermediate I-3 converts to product is not yet clear. In principle, formation of the new C-NTs bond could occur either before or after rupture of the NTs-CN bond. Intriguingly, instead of giving the corresponding four-membered benzazetidine,[33] the reaction of o-isopropenyl-substituted cyanamide 1o led to alkenyl nitrile 2o in quantitative yield (Scheme 2, bottom).[34] These results show that the type of cyano group transfer developed by Wang and Falck does not require added rhodium. Future work will explore the mechanistic consequence of this observation for aminocyanation.

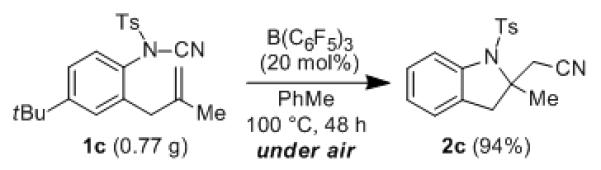

Our mechanistic hypothesis suggested that B(C6F5)3 might act as a catalyst. To test this hypothesis, 1a was treated with 20 mol % B(C6F5)3 in toluene and heated at 90 °C for an extended time (48 h). We were pleased to find that 2a was formed in 91% yield. These results indicate that the coordination of B(C6F5)3 to the product is not so strong as to preclude turnover. Due to the relatively high cost of commercial B(C6F5)3, cost-saving by catalysis may be achieved at the expense of reaction time. After a successful small-scale reaction of 1c with 20 mol % B(C6F5)3 under nitrogen, we repeated the reaction on larger scale, heating at 100 °C for 48 h under an atmosphere of air. We obtained 2c in 94% yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Catalysis with B(C6F5)3 and Reaction Under Air

In summary, we have developed a Lewis acid-promoted intramolecular aminocyanation of alkenes. The addition of transition metal catalysts or initiators is not required. We believe we have identified a new mechanistic pathway for aminative alkene difunctionalization via the addition of bench-stable, readily available, cyanamides. We demonstrated the aminocyanation reaction in the preparation of two important classes of nitrogen-heterocycles, indolines and tetrahydroquinolines in excellent yields. Current efforts are directed towards further elucidating the mechanism and expanding the scope, as well as developing intermolecular variants of aminocyanation. Further work will be directed towards development of a catalytic asymmetric variant of the reaction and further studies on the mechanism by probing the stereochemistry of the addition process.

Experimental Section

See the supporting information for experimental details.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

We thank the National Institutes of Health for primary support of this work (R01 GM095559). CJD thanks Research Corporation for Science Advancement for additional support via a Cottrell Scholar Award. We thank Dr. Joe Dalluge and Mr. Sean Murray for assistance with HRMS measurements. NMR spectra were recorded on an instrument purchased with support from the National Institutes of Health (S10OD011952).

References

- [1].Reviews: Jensen KH, Sigman MS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:4083. doi: 10.1039/b813246a. McDonald RI, Liu G, Stahl SS. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:2981. doi: 10.1021/cr100371y.

- [2].Review: Wolfe JP. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2013;32:1. Selected Examples Hegedus LS, Allen GF, Olsen DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:3583. Tamaru Y, Hojo M, Higashimura H, Yoshida Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:3994. Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Angew. Chem. 2004;116:3689. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460060. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3605. Scarborough CC, Stahl SS. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3251. doi: 10.1021/ol061057e. Sherman ES, Fuller PH, Kasi D, Chemler SR. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3896. doi: 10.1021/jo070321u. Hayashi S, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:7360. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903178. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7224. Rosewall CF, Sibbald PA, Liskin DV, Michael FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9488. doi: 10.1021/ja9031659. Rossiter LM, Slater ML, Giessert RE, Sakwa SA, Herr RJ. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:9554. doi: 10.1021/jo902114u. Bagnoli L, Cacchi S, Fabrizi G, Goggiamani A, Scarponi C, Tiecco M. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2134. doi: 10.1021/jo1002032. Brenzovich WE, Benitez D, Lackner AD, Shunatona HP, Tkatchouk E, Goddard WA, Toste FD. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:5651. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002739. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5519. Jaegli S, Erb W, Retailleau P, Vors J-P, Neuville L, Zhu J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010;16:5863. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000312. Jepsen TH, M M. Larsen,, Nielsen B. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:6133. Borsini E, Broggini G, Fasana A, Galli S, Khansaa M, Piarulli U, Rigamonti M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:985. Nicolai S, Piemontesi C, Waser J. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:4776. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100718. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:4680. Jana R, Pathak TP, Jensen KH, Sigman MS. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4074. doi: 10.1021/ol3016989.

- [3].Diazoalkane cycloadditions accomplish simultaneous C-C and C-N bond forming across alkenes: Maas G. Diazoalkanes. In: Padwa A, Pearson WH, editors. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry Toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. Wiley-Interscience; 2002. pp. 539–623.

- [4].Review: Donohoe TJ, Callens CKA, Flores A, Lacy AR, Rathi AH. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:58. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002323.

- [5].Review: Cardona F, Goti A. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:269. doi: 10.1038/nchem.256. Muñiz K, Martínez C. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:2168. doi: 10.1021/jo302472w.

- [6].Review: Mueller TE, Hultzsch KC, Yus M, Foubelo F, Tada M. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3795. doi: 10.1021/cr0306788. Zi G. Dalton Trans. 2009:9101. doi: 10.1039/b906588a.

- [7].Review: Li G, Saibau KSRS, Timmons C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:2745. Chemler SR, Bovino MT. ACS Catal. 2013;3:1076. doi: 10.1021/cs4001249.

- [8].Intramolecular diamination of alkenes is an exception (ref 5)

- [9].Hoang GT, Reddy VJ, Nguyen HHK, Douglas CJ. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:1922. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1882. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Koester DC, Kobayashi M, Werz DB, Nakao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6544. doi: 10.1021/ja301375c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Murahashi S, editor. Three Carbon-Heteroatom Bonds: Nitriles, Isocyanides, and Derivatives. Vol. 19. Georg Thieme Verlag; Stuttgart: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fatiadi A. In: Preparation and Synthetic Application of Cyano Compounds. Patai S, Rappaport Z, editors. Wiley; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Cardillo G, Tomasini C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1996;25:117. [Google Scholar]; b) Spiteller P, von Nussbaum F. Biosynthesis of β-Amino Acids. In: Schumck C, Wennemers H, editors. Highlights in Bioorganic Chemistry: Methods and Application. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]; c) Juaristi E, Soloshnok VA. Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Amino Acids. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]; d) Weiner B, Szymanski W, Janssen DB, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1656. doi: 10.1039/b919599h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang H, Pu W, Xiong T, Li Y, Zhou X, Sun K, Liu Q, Zhang Q. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:2589. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:2529. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Nekrasov DD. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2004;40:1107. [Google Scholar]; b) Larraufie M-H, Maestri G, Malacria M, Ollivier C, Fensterbank L, Lacote E. Synthesis. 2012;44:1279. doi: 10.1021/ol3026439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].von Braun J. J. Chem. Ber. 1907;40:3914–3933. Reviews: Hageman HA. Org. React. 1953;7:198. Thavaneswaran S, McCamley K, Scammells PJ. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2006;1:885. CAUTION! Cyanogen bromide (BrCN) is highly toxic and hydrolyzes readily to release hydrogen cyanide. Reactions using BrCN must be carried out in a well-ventilated fume hood.

- [17].a) Cunningham ID, Light ME, Hursthouse MB. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1999;55:1833. [Google Scholar]; b) Vliet EB. Org. Synth. 1925;5:43. [Google Scholar]; c) Rao B, Zeng X. Org. Lett. 2014;16:314. doi: 10.1021/ol403346x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fukumoto K, Oya T, Itazaki M, Nakazawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:38. doi: 10.1021/ja807896b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang R, Falck JR. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6516. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43597k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].For syntheses of 2,2-disubstituted indolines, see: Larock RC, Pace P, Yang H, Russell CE, Cacchi S, Fabrizi G. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:9961. Zhou F, Guo J, Liu J, Ding K, Yu S, Cai Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14326. doi: 10.1021/ja306631z. Cai Q, Zhou F. Synlett. 2013;24:408. Nowrouzi F, Batey RA. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:926. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207978. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:892.

- [21].Anbarasan P, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew. Chem. 2010;123:539. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:519. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Chaitanya M, Yadagiri D, Anbarasan P. Org. Lett. 2013;15:4960. doi: 10.1021/ol402201c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gong T-J, Xiao B, Cheng W-M, Su W, Xu J, Liu Z-J, Liu L, Fu Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10630. doi: 10.1021/ja405742y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Recent review: Nakao Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2012;85:731.

- [24].Nakao and co-workers observed reductive decyanation of the cyanate substrates from the oxycyanation reactions (see ref 19).

- [25].Subjecting 1m to the aminocyanation condition with [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 (5 mol%) and BPh3 (1.0 equiv) in toluene at 110 °C gave the product of decyanation (3m) and unconsumed starting material.

- [26].Kan T, Fukuyama T. Chem. Commun. 2004:353. doi: 10.1039/b311203a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wang J-B. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5608. doi: 10.1021/ol202335p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lewis acid/base pairs between isonitriles or nitriles and B(C6F5)3: Jacobsen H, Berke H, Döring S, Kehr G, Erker G, Froehlich R, Meyer O. Organometallics. 1999;18:1724. b)Lewis Acid/base pair adducts between B(C6F5)3 and cyanamides (and other nitrogen-containing compounds) Focante F, Mercandelli P, Sironi A, Resconi L. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:170. and referenes therein.

- [29].Erker G. Dalton Trans. 2005:1883. doi: 10.1039/b503688g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].B(C6F5)3 is estimated to be in between BCl3 and BF3 in Lewis acidity: Döring S, Erker G, Froehlich R, Meyer O, Bergander K. Organometallics. 1998;17:2183.

- [31].For a recent example, see: Giles RL, Sullivan JD, Steiner AM, Looper RE. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:3162. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900160. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3116.

- [32].Similarly, an equimolar mixture of 1d and 1l was subjected to the aminocyanation conditions, and only the corresponding indoline products 2d and 2l were observed. This indicates the N-S bond also remains intact during aminocyanation.

- [33].Synthesis of N-acyl benzazetidines: Kobayashi K, Miyamoto K, Morikawa O, Konishi H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2005;78:886.

- [34].2o was identified by comparing its 1H and 13C NMR spectra and HRMS data with the prior report (see ref. 19).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.