Abstract

Background

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides are cardiovascular risk factors susceptible to lifestyle behavior modification and genetics. We hypothesized that genetic variants identified by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) as associated with HDL-C or triglyceride levels will modify 1-year treatment response to an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI), relative to a usual care of diabetes support and education (DSE).

Methods and Results

We evaluated 82 SNPs, representing 31 loci demonstrated by GWAS to be associated with HDL-C and/or triglycerides, in 3,561 participants who consented for genetic studies and met eligibility criteria. Variants associated with higher baseline HDL-C levels, cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) rs3764261 and hepatic lipase (LIPC) rs8034802, were found to be associated with HDL-C increases with ILI (p=0.0038 and 0.013, respectively) and had nominally significant treatment interactions (p=0.047 and 0.046, respectively). The fatty acid desaturase-2 (FADS-2) rs1535 variant, associated with low baseline HDL-C (p=0.017), was associated with HDL-C increases with ILI (0.0037) and had a nominal treatment interaction (p= 0.035). ApoB (rs693) and LIPC (rs8034802) SNPs showed nominally significant associations with HDL-C and triglyceride changes with ILI and a treatment interaction (p<0.05). A PGS1 SNP (rs4082919) showed the most significant triglyceride treatment interaction in the full cohort (p=0.0009).

Conclusions

This is the first study to identify genetic variants modifying lipid responses to a randomized lifestyle behavior intervention in overweight/obese diabetic individuals. The effect of genetic factors on lipid changes may differ from the effects on baseline lipids and are modifiable by behavioral intervention.

Keywords: genomics, physiological, cholesterylester transfer protein genetics, triglycerides, behavior modification, lipoprotein

Introduction

Significant changes in eating and physical activity behaviors that cause weight loss can improve insulin resistance and other biological markers relevant to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in patients who are obese and have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D)1. Lifestyle modification is first-line therapy in efforts to raise high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and to lower triglyceride levels2. However, the response to behavioral intervention is inconsistent. HDL-C and triglycerides levels are heritable3, 4 as are lipid responses to overfeeding5 and exercise training6, suggesting that genetic factors contribute to the lipid response to behavioral intervention. What is currently largely unknown is which common genetic factors influence or predict the HDL-C and/or triglyceride level response to behavior modification. Collectively, GWASs have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in at least 95 loci, the combined effects of which combined effects account for approximately 10–12% of the total variance in HDL-C and triglyceride levels7.

The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study is a multi-center trial that randomly assigned participants with T2DM who were overweight or obese to an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI), with the goal of producing 7% weight loss through calorie restriction and physical activity, or to Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) with no weight loss or physical activity goals8. Compared with large observational cohort studies, the Look AHEAD study has the unique strength of being able to analyze the effect of genetic factors on lipid trait change in response to two randomly assigned behavioral interventions. At baseline (year-0), the majority of Look AHEAD participants demonstrated decreased fitness9, and consumed a diet that exceeded recommended nutrient intake for total fat and saturated fat with reduced fiber content10. After the first year (year-1), participants in the ILI arm lost significantly greater amounts of weight, and showed greater improvement in fitness, waist circumference and indices of diabetes control including metabolic syndrome, diabetes medication use, hemoglobin A1-c and fasting glucose, compared with participants in the DSE arm11. Participants in both groups demonstrated improved HDL-C and triglyceride levels at year-1; however the ILI group showed greater improvements compared with the DSE group11. Changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were similar in both groups.

Gene variants that modify the behavioral treatment response of HDL-C and triglycerides may have potential for directing personalized medical or behavioral treatment programs. With this overarching goal we hypothesized that GWAS-identified SNPs associated with HDL-C and triglyceride levels are also associated with HDL-C and triglyceride responses to the behavioral therapy implemented in Look AHEAD. To test this hypothesis we examined the interaction of SNP with treatment arm at 1-year and analyzed the HDL-C and triglyceride response to ILI and DSE between Look AHEAD carriers of the minor allele of HDL-C and triglyceride SNPs included on the IBC array..

Material and Methods

Detailed methods are described in the Supplement. Of 4,099 Look AHEAD participants whose DNA was collected, 353 subjects taking niacin or fibrates were excluded because of their effects on HDL-C and triglycerides and 185 were excluded due to genotyping failure yielding an effective sample size of 3,561 participants. All participants included in this study signed informed consent for participation in the Look AHEAD trial and genetic analyses with Institutional Review Board approval at their local institution; this analysis was approved by the Tufts Medical Center and Miriam Hospital Institutional Review Boards. Genotyping was performed using the IBC chip. A search of published literature using the HUGE Navigator in April 2012 for HDL-C and triglycerides GWASs returned 89 SNPs associated with HDL-C alone, 48 SNPs associated with triglycerides alone, and 22 SNPs associated with both HDL-C and triglycerides; 82 SNPs were selected for this study that were either a GWAS SNP or a proxy for a GWAS SNP (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). HDL-C and TG levels were measured after a greater than 12-hour fast11. Non-transformed HDL-C and log-transformed triglyceride levels were analyzed (Supplemental Figure 1).

Baseline and 1-year measurements for each outcome of interest were modeled jointly, as bivariate normal variables with an unstructured covariance matrix. Three-way interaction models of individual SNP markers with measurement time (1-year vs. baseline) and study arm (ILI vs. DSE) were estimated in Splus 8.212 using restricted maximum likelihood. An additive genetic model was used for all SNP markers, with genotype coded by the number of minor alleles (0/1/2 copies). Therefore, four distinct types of SNP effects were estimated, which can be interpreted as the effect of one additional copy of the corresponding minor allele on a) baseline lipid levels within DSE (SNP main effect), b) ILI-DSE differences in baseline lipid levels (SNP*treatment interaction), c) 1-year change in lipids within DSE (SNP* time*treatment interaction), and d) ILI-DSE differences in 1-year change in lipids (SNP* time * treatment interaction). Set (b) model parameters serve as a randomization check. No between-arm differences in baseline means were detected for any of the markers under consideration.

All our results are based on full 3-way hierarchical interaction models, with no additional model simplification. To aid with the interpretation of SNP*time*treatment interactions, we report marker effects on 1-year change separately for ILI and DSE. Main marker effects at baseline include all participants from both study arms.

Longitudinal outcomes were additionally adjusted for age, gender, hormonal replacement therapy at baseline, concurrent drug use (lipid medication, thiazolidindione medication, with pioglitazone and rosiglitazone effects modeled separately), study site, and the first two ancestry informative marker principal components (Supplemental Methods) as previously described13, 14. Other than study site, all of these covariates were fully interacted with time, treatment, and time by treatment interaction, so as to allow for these covariate effects to vary across study arm and/or time point, in a manner similar to the SNP effects described above.

Using the method of Li and Ji15 for our experiment of 82 SNPs, we computed our multiplicity-adjusted threshold for significance of SNP main effects on baseline outcomes as p<0.0009, taking into account the effective number of uncorrelated markers being tested. However, since we expect SNP*treatment interactions to have smaller effect size than SNP main effects, we chose to report all such interaction findings that reached a p<0.05 threshold for nominal significance16. The locus-wide threshold significance used in regional plots was p<2.9 × 10−6 using the approach described by Li and Ji15.

Results

Look AHEAD Genetic Study

Baseline characteristics of Look AHEAD study participants not taking fibrates or niacin for whom genotype data from the IBC array were available are shown in Table 1. Significant differences in year-1 lipid and thiazolidindione medication use were observed between participants in the DSE and ILI groups (Table 1 and11), with statin use increasing in ILI to a lesser extent than in DSE. Look AHEAD Genetics Study participants in the ILI group showed highly significant year-1 differences in HDL-C and triglycerides as compared to participants in the DSE group (both p<0.0001; see Table 1). However, they did not differ in terms of either LDL (p=0.48) or total cholesterol (p=0.26).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics in Look AHEAD Genetic Sub-Cohort

| Characteristic | Total (N= 3,561) | DSE (N=1,797) | ILI (N=1,764) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (%) | 57.9 | 57.5 | 58.3 |

| Age in years (SD) | 59.0 (6.9) | 59.0 (6.8) | 59.1 (6.9) |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 605 (17.0) | 295 (16.4) | 310 (17.6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Nativea | 18 (0.5) | 8 (0.4) | 10 (0.6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 41 (1.1) | 19 (1.1) | 22 (1.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 267 (7.5) | 136 (7.6) | 131 (7.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2555 (71.7) | 1298 (72.2) | 1257 (71.2) |

| Other (multiple) | 75 (2.1) | 41 (2.3) | 34 (1.9) |

| Y0 Medication Use (%) | |||

| Statin | 46.5 | 46.7 | 46.2 |

| Rosiglitazone | 15.0 | 15.7 | 14.2 |

| Pioglitazone | 12.5 | 12.7 | 12.2 |

| HRT (% women) | 58.2 | 58.6 | 57.9 |

| Y1 Medication Use (%) | |||

| Statin | 52.1 | 55.1 | 49.1 |

| Rosiglitazone | 14.8 | 16.9 | 12.6 |

| Pioglitazone | 12.3 | 14.4 | 10.1 |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) (Mean (SD)) | |||

| Year 0 | 36.2 (6.06) | 36.16 (5.9) | 36.3 (6.22) |

| Year 1 | 34.4 (6.24) | 35.77 (5.94) | 33.02 (6.24) |

| Year 1-0 Change | −1.89 (2.72) | −0.33 (2.83) | −3.25 (2.61) |

|

| |||

| HDL-C (mg/dl) (Mean (SD)) | |||

| Year 0 | 43.73 (11.9) | 43.7 (11.8) | 43.8 (12.0) |

| Year 1 | 46.1 (12.5) | 45.18 (11.96) | 47.1 (13.0) |

| Year 1-0 Change | 2.28 (7.03) | 1.3 (7.2) | 3.24 (6.83) |

|

| |||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) (Median (IQR) | |||

| Year 0 | 151 (106 to 217) | 150 (107 to 214) | 152 (106 to 218) |

| Year 1 | 139 (94 to 191) | 142 (100 to 300) | 128 (90 to 180) |

| Year 1-0 Change | −12 (−49.25 to 20) | −5 (−40 to 26) | −19 (−62 to 12) |

|

| |||

| Log Triglyceride (Mean (SD)) | |||

| Year 0 | 5.02 (0.54) | 5.02 (0.53) | 5.02 (0.54) |

| Year 1 | 4.91 (0.53) | 4.96 (0.52) | 4.85 (0.53) |

| Year 1-0 Change | −0.12 (0.41) | −0.05 (0.42) | −0.18 (0.41) |

The number of American Indian participants included in this study is proportionally less than the parent Look AHEAD trial due to limitations in genetic consent.

SNPs Associated with Baseline Lipid Traits and Treatment Response

SNPs showing an interaction with response to behavioral treatment for HDL-C and log-transformed triglyceride levels below a level of nominal significance (SNP*treatment p<0.05) are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively, while SNPs showing an association with baseline levels averaged across the 2 study arms below a significance threshold corrected for multiple hypothesis testing specific to this analysis (p<0.0009) are shown in Supplemental Tables 4 and 5. Out of 82 SNPs selected for analysis based upon prior HDL-C or triglyceride GWASs, we identified 20 SNPs associated with baseline HDL-C levels and 12 SNPs that demonstrated evidence of behavioral treatment effect modification; CETP rs3764261 showed both a significant baseline HDL-C association and a nominal treatment interaction. For triglyceride levels, we identified 27 SNPs associated with baseline levels, and 6 SNPs that demonstrated evidence of behavioral treatment effect modification. SNPs in lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) were associated with both baseline HDL-C and triglycerides. Polymorphisms in cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) and lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) were found to be only associated with baseline HDL-C while SNPs in angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR), propionyl-CoA carboxylase beta chain (PCCB), tribbles-like protein 1 (TRIB1), FADS-2, and cartilage intermediate layer protein 2 (CILP2) were only associated with baseline triglyceride levels. The direction of effect of significant minor allele association with baseline HDL-C and triglyceride levels in Look AHEAD agreed with the published GWAS association. The replication of many GWAS HDL-C and triglyceride SNP associations with baseline Look AHEAD measures indicates that these SNP associations are unlikely to be weakened significantly by T2D and obesity.

Table 2.

Genetic predictors of year 1 change in HDL-C

| Gene | SNP | Group | N | Major Allele | Minor Allele/GWAS Effect | MAF | Baseline HDL | 1-Year HDL Change | SNP* Tx Interaction P-values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILI and DSE | ILI | DSE | ||||||||||||||

| Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | ||||||||

| APOB | rs693* | All | 3559 | G | A↓ | 42.50 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.4089 | −0.51 | 0.27 | 0.0597 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.2995 | 0.0385 |

| NHW | 2544 | G | A↓ | 47.86 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.5474 | −0.56 | 0.30 | 0.0606 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.3399 | 0.0458 | ||

| GCKR | rs1260326 | All | 3559 | G | A | 35.21 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.5008 | −0.50 | 0.28 | 0.0729 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.0937 | 0.0141 |

| NHW | 2544 | G | A | 40.41 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.0289 | −0.56 | 0.31 | 0.0683 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.2260 | 0.0311 | ||

| GCKR | rs780094 | All | 3560 | G | A | 35.39 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.6769 | −0.46 | 0.27 | 0.0952 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.1461 | 0.0272 |

| NHW | 2545 | G | A | 39.80 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.0684 | −0.52 | 0.31 | 0.0916 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.1948 | 0.0345 | ||

| GCKR | rs780093 | All | 3526 | G | A | 34.91 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.4715 | −0.48 | 0.28 | 0.0799 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.1181 | 0.0190 |

| NHW | 2524 | G | A | 39.85 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.0605 | −0.54 | 0.30 | 0.0767 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.1959 | 0.0299 | ||

| FADS1 | rs174548 | All | 3557 | G | C↓ | 29.10 | −0.46 | 0.29 | 0.1086 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.0132 | −0.17 | 0.28 | 0.5566 | 0.0295 |

| NHW | 2542 | G | C↓ | 27.95 | −0.66 | 0.31 | 0.0340 | 0.89 | 0.33 | 0.0073 | −0.11 | 0.33 | 0.7451 | 0.0326 | ||

| FADS2 | rs1535 | All | 3559 | A | G | 31.33 | −0.67 | 0.28 | 0.0174 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.0037 | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.9479 | 0.0352 |

| NHW | 2544 | A | G | 32.19 | −0.64 | 0.30 | 0.0316 | 0.79 | 0.32 | 0.0120 | −0.02 | 0.31 | 0.9462 | 0.0664 | ||

| ZNF259 | rs12286037 | All | 3561 | G | A | 9.03 | −0.26 | 0.45 | 0.5631 | −0.77 | 0.44 | 0.0819 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.2808 | 0.0472 |

| NHW | 2546 | G | A↓ | 6.34 | −0.39 | 0.57 | 0.5000 | −0.27 | 0.63 | 0.6697 | 0.24 | 0.59 | 0.6864 | 0.5570 | ||

| LIPC | rs1800588* | All | 3558 | G | A↑ | 27.97 | 0.86 | 0.30 | 0.0041 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 0.0037 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.8997 | 0.0488 |

| NHW | 2543 | G | A↑ | 20.74 | 1.03 | 0.34 | 0.0026 | 1.04 | 0.36 | 0.0044 | −0.22 | 0.36 | 0.5413 | 0.0141 | ||

| LIPC | rs8034802* | All | 3555 | T | A↑ | 31.05 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.0225 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.0131 | −0.09 | 0.28 | 0.7511 | 0.0463 |

| NHW | 2542 | T | A↑ | 27.45 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.0345 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.0081 | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.9571 | 0.0522 | ||

| LIPC | rs588136* | All | 3558 | A | G↑ | 26.41 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.0078 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.1033 | −0.15 | 0.30 | 0.6249 | 0.1324 |

| NHW | 2543 | A | G↑ | 20.78 | 1.09 | 0.34 | 0.0013 | 0.94 | 0.37 | 0.0106 | −0.23 | 0.35 | 0.5210 | 0.0223 | ||

| CETP | rs3764261 | All | 3559 | C | A↑ | 31.48 | 2.79 | 0.27 | 2.5*10−24 | 0.81 | 0.28 | 0.0038 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.9034 | 0.0471 |

| NHW | 2546 | C | A↑ | 31.63 | 2.70 | 0.30 | 1.5*10−19 | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.0366 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.9952 | 0.1326 | ||

| LILRA3 | rs103294 | All | 3561 | G | A↑ | 18.35 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.2867 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.4887 | −0.70 | 0.33 | 0.0340 | 0.0472 |

| NHW | 2546 | G | A↑ | 18.87 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.1073 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.6522 | −0.38 | 0.38 | 0.3052 | 0.2976 | ||

indicates both HDL-C and Triglyceride SNP*Tx Interaction association. Age, gender, ancestry principal components, and study site statistically adjusted. All analyses quantify the effect of additional copies of the minor allele in an additive model. Baseline p-values less than 0.0009 and interaction and 1-year p-values less than 0.05 shown in bold. Arrows indicate the direction of the HDL-C effect published in GWASs (Supplemental Table 1 and 3). ALL, all racial and ethnic groups.

Table 3.

Genetic predictors of year 1 change in triglycerides (logarithmic scale)

| Gene | SNP | Group | N | Major Allele | Minor Allele/GWAS Effect | MAF | Baseline log(TRIG) | 1-Year log(TRIG) Change | SNP* Tx Interaction P-values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILI and DSE | ILI | DSE | ||||||||||||||

| Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | ||||||||

| APOB | rs693* | ALL | 3559 | G | A | 42.2 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5415 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0111 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.9150 | 0.0833 |

| NHW | 2544 | G | A | 47.86 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.4078 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0065 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.3074 | 0.0083 | ||

| AFF1 | rs3775214 | ALL | 3559 | A | G↓ | 34.39 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.9102 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.3673 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0141 | 0.0177 |

| NHW | 2545 | A | G↓ | 38.53 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5502 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2725 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0265 | 0.0192 | ||

| LIPC | rs1800588* | ALL | 3558 | G | A↑ | 27.97 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.6773 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2336 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.3642 | 0.1377 |

| NHW | 2543 | G | A↑ | 20.74 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.5658 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1141 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1306 | 0.0288 | ||

| LIPC | rs8034802* | ALL | 3555 | T | A↑ | 31.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.6744 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.0817 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2745 | 0.0447 |

| NHW | 2545 | T | A↑ | 27.45 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.5854 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0406 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.0680 | 0.0061 | ||

| LIPC | rs588136* | ALL | 3558 | A | G↑ | 26.41 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.8066 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2687 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0106 | 0.0099 |

| NHW | 2543 | A | G↑ | 20.78 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.7661 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0848 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0238 | 0.0050 | ||

| PGS1 | rs4082919 | ALL | 3561 | C | A | 44.72 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.0219 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.0619 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0048 | 0.0009 |

| NHW | 2546 | C | A | 47.68 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.1520 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.0607 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1379 | 0.0176 | ||

indicates both HDL-C and Triglyceride SNP*Tx Interaction association. Age, gender, ancestry principal components, and study site statistically adjusted. All analyses quantify the effect of additional copies of the minor allele in an additive model. Interaction and 1-year P-values less than 0.05 shown in bold. Arrows indicate the direction of the triglyceride effect published in GWASs (Supplemental Table 1 and 3). ALL, all racial and ethnic groups.

In agreement with previous studies17, 18, numerous LPL SNPs were associated with both baseline HDL-C and triglyceride levels in Look AHEAD. LPL rs17410962 was most strongly associated with baseline HDL-C (beta ± SE = 2.41 ± 0.36 mg/dL, p=3.6*10−11) and log(triglycerides) (beta ± SE= −0.12 ± 0.02, p=1.4*10−10). In the original scale of the data, this implies an 11% reduction in baseline triglyceride levels per copy of the minor allele (beta=0.89, 95% CI= 0.85–0.92). PLTP SNP rs6065904 was also found to be significantly associated with baseline HDL-C and triglyceride levels. LPL and PLTP minor allele carriers however demonstrated year-1 changes in lipid traits that were in the same direction in the DSE and ILI treatment groups with a non-significant SNP*treatment interaction p-value. The lack of a treatment response association for LPL and PLTP SNPs indicated that genetic variants significantly associated with baseline HDL-C and triglyceride levels do not necessarily predict behavioral treatment response.

Genetic Predictors of Differential Lipid Level Response to Behavioral Therapy

Three Hepatic lipase (LIPC) SNPs demonstrated evidence of behavioral treatment effect modification at year-1 for both HDL-C and triglyceride change (Tables 2 and 3), in either the full Look AHEAD cohort or just in NHW participants. LIPC rs8034802 minor allele carriers showed a greater increase with ILI compared with DSE for HDL-C (ILI per allele change ± SE = 0.70 ± 0.28 (p = 0.013) vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = −0.09 ± 0.28 (p = 0.75), nominal SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.046) and a greater decrease in log(triglycerides) (ILI per allele change ± SE = −0.03 ± 0.02 (p = 0.082) vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = 0.02 ± 0.02 (p = 0.27), SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.045). The direction of treatment effect was opposite for HDL-C and triglycerides. LIPC is known to biologically modify triglycerides and HDL-C, and here, we demonstrate that LIPC variants are associated with the triglyceride and HDL-C response to a lifestyle intervention designed to reduce obesity and to increase physical fitness.

Genes selectively associated with HDL-C response

Of SNPs associated with baseline HDL-C or triglycerides, only one SNP strongly associated with baseline trait levels was also associated with a significant behavioral treatment response. CETP rs3764261, was strongly associated with baseline HDL-C (p = 2.5*10−24) and nominally associated with HDL-C change in response to ILI (p = 0.0038) and showed a nominal treatment interaction at year-1 (SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.047) in the full Look AHEAD cohort. The HDL-C increase in minor allele carriers of rs3764261 in the ILI group was lower in NHW participants compared with all Look AHEAD participants and the SNP*treatment interaction no longer reached significance (p=0.13).

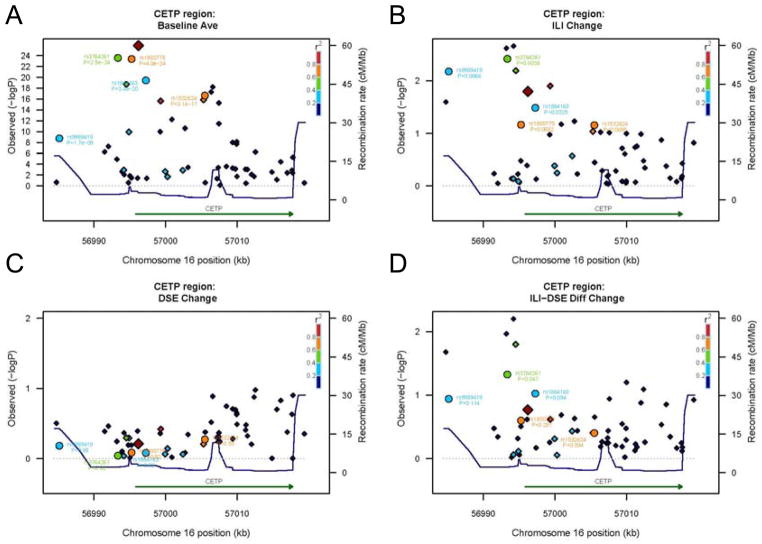

To illustrate the genotypic effect of CETP rs3764261 upon HDL-C change in the entire Look AHEAD cohort, we calculated the expected HDL-C treatment response of 60-year-old men and women in the absence of lipid medication, pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, based on our longitudinal statistical model. In response to ILI in both men and women CETP rs3764261 minor allele carriers showed a greater increase in HDL-C than non-carriers (0.81 mg/dl per minor allele copy, 95% CI=0.26–1.36), with no significant difference by minor allele status observed in the DSE group (Figure 1 and Table 2). Stratification of the treatment effects by gender and genotypic group revealed a highly significant HDL-C response to ILI compared with DSE within each stratum (all p<0.002), with the exception of female homozygous carriers of the major allele (CC) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HDL-C Behavioral Treatment Response by CETP rs3764261 genotype. Graph shows model predictions from the Look AHEAD cohort for the mean and 95% CI HDL-C difference (Year 1-0) by CETP rs3764261 genotype as predicted for 60-year old men and women not receiving a lipid lowering medication, pioglitazone or rosiglitazone randomized to ILI (black dots) and DSE (shaded dots). The HDL-C difference in women was adjusted for the presence of hormone replacement therapy. The presence of one or more minor alleles in men and women was significantly associated with increased HDL-C change in the setting of ILI (p=0.0038 for both), but not for DSE (p=NS for both). The HDL-C difference was significantly greater in the participants given ILI compared with DSE (**, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001), except for women CC carriers.

By comparison, the minor allele at zinc finger 259 (ZNF259) rs12286037, which GWAS predicted to be associated with a reduced HDL-C, showed a nominally significant treatment interaction (SNP*treatment interaction p=0.047) with a trend towards a lower HDL-C in response to behavioral intervention (p=0.082). APOB rs693 showed a nominally significant treatment response (ILI per allele change ± SE = −0.51 ± 0.27 vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = +0.27 ± 0.26, SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.0385) with the overall ILI treatment response in the same direction as predicted by GWAS. Finally, LIPC rs8034802 minor allele carriers showed a higher baseline HDL-C and a greater increase in HDL-C in response to ILI and not DSE. These findings indicate that ILI may strengthen the genetic association by promoting HDL-C change in the same direction as at baseline.

In response to behavioral treatment FADS2 rs1535 minor allele carriers demonstrated a significantly positive HDL-C response and nominal treatment interaction (ILI per allele change ± SE = +0.82 ± 0.28, p = 0.0037 vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = −0.02 ± 0.28, p = 0.95, SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.035). SNPs in GCKR selected for analysis based upon their association with triglycerides were found to have a nominally significant SNP*treatment interaction for HDL-C including GCKR-P446L (rs1260326), which in ILI showed a per allele change ± SE = −0.50 ± 0.28 vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = +0.45 ± 0.27 and SNP*treatment interaction p = 0.014.

Genes selectively associated with triglyceride response alone

No SNP associated with baseline log(triglycerides) also showed a SNP*Tx interaction for triglyceride response to behavioral intervention. A single SNP in AF4/FMR2 family member 1 (AFF1), APOB, PGS1 and three LIPC SNPs showed a nominally significant triglyceride behavioral treatment interaction (Table 3). The strongest association with log(triglycerides) change was found with phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase-1 (PGS1) rs4082919 (ILI per allele change ± SE = −0.03 ± 0.02 vs. DSE per allele change ± SE = +0.04 ± 0.02, SNP*treatment interaction p <0.0009). Converting to the original measurement scale, this corresponds to a 3% reduction in triglyceride change within ILI per copy of the minor allele (beta=0.97, 95% CI=0.93–1.01) vs. a 4% increase within DSE (beta=1.04, 95% CI=1.00–1.08). None of the SNPs showed a significant change in HDL-C in response to ILI.

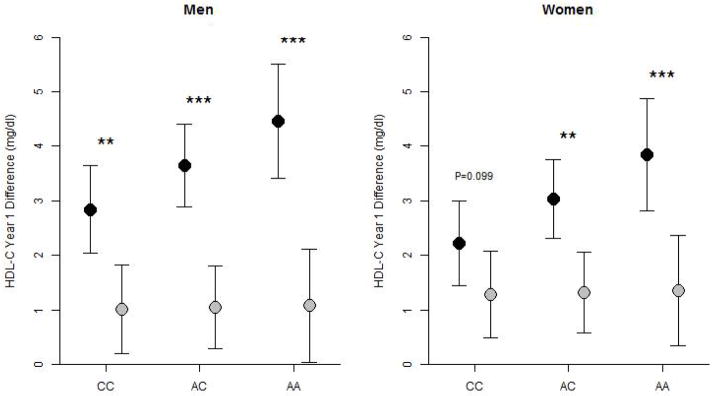

Novel SNPs Associated with Differential Lipid Trait Response to Behavioral Therapy

We next asked whether alternate SNPs within CETP, LPL, LIPC, BUD13-APOA1 Region, FADS1/2/3, GCKR, and LCAT-DPEP2 that regulate HDL-C and triglyceride were more strongly associated with differential lipid trait response compared with the GWAS SNPs. Regional plots showing associations for baseline HDL-C, year-1 change with DSE and ILI and differential change are shown for CETP in Figure 2A–D. Interestingly we observed SNPs nominally associated with HDL-C change within ILI and differential ILI-DSE response (p<0.05) in the 5′-region of CETP, which is the same region in which SNPs were highly associated with baseline HDL-C levels. We identified SNPs in LIPC, BUD13-APO complex, and FADS1/2/3, but not LPL or LCAT-DPEP2, that were significantly associated with differential change for each locus (Supplemental Figure 2A–F). However, none of these locus-wide SNPs showed an association markedly stronger than that of the GWAS SNPs.

Figure 2.

CETP locus SNP association with HDL-C response to DSE and ILI. CETP regional plot including all SNPs available on the IBC assay in Look AHEAD with their genomic location and −log(p-value) for trait association. SNPs identified by GWAS to be associated with baseline HDL-C (circles) are indicated by name with their p-value for each comparison; all other SNPs are represented as diamonds. The colors represent the strength of the LD between the selected top SNP and each marker. The top SNP always has the darkest red color. r2 values calculated with respect to the SNP marker showing the most significant associations with baseline values of the trait of interest.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the largest study to analyze the interaction of genetic factors with a randomly assigned behavioral intervention on lipid trait change in the setting of established T2D. The role of genetic factors in polygenic dyslipidemia has been well defined, and examples of genetic modification of lipid behavioral treatment response have begun to emerge19, 20. Here, we present findings from Look AHEAD, taking advantage of the unique strength of the randomized trial study design in which the two standardized behavioral interventions (ILI and DSE) were randomly assigned, with ILI producing greater improvements in HDL-C and triglyceride levels relative to DSE at one year of follow-up11, 21. While we replicate the association of many SNPs with baseline HDL-C and triglyceride levels, including several SNPs achieving a “genomic level” of significance, interestingly, only one SNP, CETP rs3764261, was strongly associated with baseline HDL-C and predicted behavioral treatment response. CETP rs3764261 showed a minor allele dose- HDL-C difference at year-1 with ILI, but not with DSE. Strikingly, women in the full Look AHEAD cohort who carried both major alleles (CC) did not have a significant HDL-C response to ILI suggesting HDL-C resistance to behavioral treatment (Figure 1). Similarly, minor alleles within GCKR, APOB and ZNF259 predicted “resistance” to HDL-C improvement.

The Women’s Genome Health Study16, a prospective cohort study of healthy women, previously demonstrated significant effect modification for CETP SNP (rs1532624) with physical activity. Here, we demonstrate that rs3764261, which is modestly correlated with rs1532624 (r2=0.59), minor allele carriers had a greater increase in HDL-C in response to ILI with a significant SNP*treatment interaction (interaction p=0.047). By comparison, Sarzynski et al.22 found that rs3764261 did not modify the HDL-C response following bariatric surgery, which does not have a fitness intervention. We were unable to replicate findings from the Women’s Genome Health Study for LPL (rs10096633 which we studied with rs17410962, r2=0.96) and LIPG (rs4939883, which we studied with rs2156552, r2=0.95). Differences between the Women’s Genome Health Study and Look AHEAD participants may explain our results. Look AHEAD includes both men and women, all participants have T2D, and a median BMI of ~36 kg/m2, while Women’s Genome Health Study participants have a very low incidence of T2D and on were not overweight (median BMI 24.1–25.7 kg/m2). Look AHEAD participants also received a randomized, controlled behavioral intervention in the ILI arm, while the Women’s Genome Health Study observed genotype associations in the setting of usual self-reported physical activity. Collectively, our findings suggest genetic variation in CETP can modify HDL-C response to lifestyle intervention.

Three LIPC variants were associated with both HDL-C and to a lesser degree with triglyceride response treatment interaction in the entire Look AHEAD cohort or the NHW subset including the LIPC-514(C/T) polymorphism (rs1800588), which has been associated with LPL expression23, activity24 and particularly in the setting of a low fat diet25, 26. We found that LIPC-514(C/T) (rs1800588) minor allele carriers showed a significantly greater HDL-C increase in response to ILI and not in response to DSE.

We identified significant HDL-C treatment interactions with SNPs previously associated with diet and metabolic factors. The Diabetes Prevention Program demonstrated an interaction of GCKR-P446L (rs1260326) with a lifestyle intervention on triglyceride levels19. In Look AHEAD GCKR-P446L modified the behavioral treatment response of HDL-C but not triglyceride, although it selectively was associated with baseline triglyceride levels. GCKR-P446L has been shown to be associated with reduced GCKR expression, lower glucose-stimulated GCK inhibitory activity27 and to interact with plasma N-3 polyunsaturated fat levels modulating fasting insulin levels and inflammatory markers28. GCKR rs780094 also interacts with dietary whole grain-intake on fasting insulin levels29, and modifies the HDL-C response to behavioral treatment. FADS1/2/3 locus SNPs described here have an association with differential HDL-C response to behavioral intervention have previously been associated with LDL response to dietary PUFA30. APOB rs693, which has important effects on LDL-C31, was found here to be associated with the HDL-C behavioral treatment response. It is worth emphasizing that weight loss in Look AHEAD participants, particularly in the ILI group, correlated with meal replacement consumption32 and cessation of binge eating practices33. We speculate that improved diet in ILI participants contributes to the differential genetic associations of GCKR, FADS1/2/3 and APOB SNPs with year-1 HDL-C changes.

LIPC, AFF1 and PGS1 SNPs which showed nominally significant treatment interactions for triglycerides all showed significant associations with triglyceride change in the DSE group and not in the ILI group. These examples suggest that genetic variants may have an effect on TG change observable only in more sedentary people with a stable weight. We interpret this finding to indicate that the influence of genetic factors on triglyceride response may not be capable of modifying the response to an intensive behavioral intervention designed to achieve weight loss and improved fitness. PGS1 rs4082919 showed the strongest SNP*treatment interaction for triglyceride response, which is surprising because that SNP was included in our analysis based upon its association with HDL-C and not triglycerides7. By comparison, GCKR SNPs included in the analysis because of their association with triglyceride levels7 showed a SNP*treatment interaction for HDL-C and not triglycerides. These examples indicate that SNPs associated with baseline traits may modify the treatment response of a related biomarker.

We did not identify any novel SNPs included in the genes under study that affect HDL-C or triglyceride response to behavioral intervention. We cannot exclude the possibility of there being genomic loci that modify HDL-C and triglyceride behavioral treatment response somewhere in the genome. Future genome-wide association analysis will allow the determination whether common gene variants modify behavioral treatment response.

We recognize several limitations of our study. First, the size of Look AHEAD is smaller than many GWASs and therefore our ability to replicate SNP associations with baseline lipid levels or to distinguish their effect on behavioral treatment response was limited. Second, we acknowledge that our findings of genotype-treatment response interaction cannot be tested in a replication cohort since there is currently no cohort available with similar enrollment criteria subject to a randomized behavioral treatment. Further, we report nominally significant interaction p-values below 0.05 that do not surpass our experiment-wide significance threshold used for testing main SNP effects on baseline outcomes. SNP*treatment interactions are likely to have smaller effect sizes than SNP main effects, suggesting that p-values below 0.05, but above the threshold corrected for multiple testing, may still be informative. However, we acknowledge that because of a lack of replication and the nominal significance of our interaction p-values our findings must be considered hypothesis-generating. Third, while SNPs studied here were selected on the basis of their prior association with HDL-C and/or triglycerides by well powered GWASs we cannot exclude the possibility that there are other important gene variants that influence HDL-C and triglyceride response to behavioral intervention that were not studied. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that SNP associations demonstrated here may have been influenced by unappreciated genetic structure within the population. We sought to control for population stratification through the inclusion of the first two principal components derived from ancestry informative markers as covariates in our models; an approach that for cardiovascular disease risk factors yields information very close to self-reported race34 while offering the ability to classify race and ethnicity for every available Look AHEAD participant. In addition, we find that association results for Look AHEAD participants who self-reported their race and ethnicity as NHW were very similar to the results from the entire cohort. We acknowledge that our results in Look AHEAD may be most reflective of NHWs and may not be generalizable to all racial and ethnic groups. Finally, we acknowledge that although our findings from Look AHEAD may apply to a growing population of individuals with T2D, our findings may not be generalizable to a non-diabetic population.

Overall, our findings demonstrate evidence that select variants contained within genes that have undisputed roles in lipid traits appear to modify HDL-C and/or triglyceride response to lifestyle intervention. However, the effect of genetic factors on lipid responses to behavioral intervention may not be consistently predicted by their baseline associations and are susceptible to modification. These results provide new insight into the biology of HDL-C and triglycerides and demonstrate the genetic effects on the response to an environmental change. It should be noted that all of the individual genetic effects were smaller than the aggregate HDL-C and triglyceride responses to ILI. Therefore, we conclude that while there is evidence of significant effect modification, individual genetic factors do not prevent favorable HDL-C and triglyceride response to behavioral treatment. Collectively, we conclude that an intensive behavioral intervention for T2D and obesity is effective despite the presence of genetic factors that resist HDL-C and triglyceride responses.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest to disclose.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Anderson JW, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ. Importance of weight management in type 2 diabetes: review with meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22:331–339. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, Ginsberg HN, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perusse L, Rice T, Despres JP, Bergeron J, Province MA, Gagnon J, et al. Familial resemblance of plasma lipids, lipoproteins and postheparin lipoprotein and hepatic lipases in the HERITAGE Family Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3263–3269. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orru M, Albai G, Dei M, et al. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Poehlman ET, Theriault G, Nadeau A, et al. Sensitivity to overfeeding: the Quebec experiment with identical twins. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1988;12:45–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Despres JP, Moorjani S, Tremblay A, Poehlman ET, Lupien PJ, Nadeau A, et al. Heredity and changes in plasma lipids and lipoproteins after short-term exercise training in men. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:402–409. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray G, Gregg E, Haffner S, Pi-Sunyer XF, WagenKnecht LE, Walkup M, et al. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:202–215. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribisl PM, Lang W, Jaramillo SA, Jakicic JM, Stewart KJ, Bahnson J, et al. Exercise capacity and cardiovascular/metabolic characteristics of overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2679–2684. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitolins MZ, Anderson AM, Delahanty L, Raynor H, Miller GD, Mobley C, et al. Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial: baseline evaluation of selected nutrients and food group intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1367–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Bright R, Clark JM, et al. Yanovski SZ. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TIBCO Spotfire SPLUS 8.2 for Solaris/Linux User’s Guide. Seattle, WA: TIBCO Software, Inc; 2010. TIBCO Software I. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCaffery JM, Papandonatos GD, Peter I, Huggins GS, Raynor HA, Delahanty LM, et al. Obesity susceptibility loci and dietary intake in the Look AHEAD Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:1477–1486. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCaffery JM, Papandonatos GD, Huggins GS, Peter I, Kahn S, Knowler WC, et al. FTO predicts weight regain in the Look AHEAD Clinical Trial. International Journal of Obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.54. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb) 2005;95:221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad T, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Lee IM, Ridker PM, Everett BM. Physical activity modifies the effect of LPL, LIPC, and CETP polymorphisms on HDL-C levels and the risk of myocardial infarction in women of European ancestry. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:74–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, Surti A, Burtt NP, Rieder MJ, et al. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:189–197. doi: 10.1038/ng.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:161–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollin TI, Jablonski KA, McAteer JB, Saxena R, Kathiresan S, Kahn SE, et al. Triglyceride response to an intensive lifestyle intervention is enhanced in carriers of the GCKR Pro446Leu polymorphism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1142–1147. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollin TI, Isakova T, Jablonski KA, de Bakker PI, Taylor A, McAteer J, et al. Genetic modulation of lipid profiles following lifestyle modification or metformin treatment: the Diabetes Prevention Program. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1566–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarzynski MA, Jacobson P, Rankinen T, Carlsson B, Sjostrom L, Carlsson LM, et al. Association of GWAS-based candidate genes with HDL-cholesterol levels before and after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E953–957. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen JC, Wang Z, Grundy SM, Stoesz MR, Guerra R. Variation at the hepatic lipase and apolipoprotein AI/CIII/AIV loci is a major cause of genetically determined variation in plasma HDL cholesterol levels. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2377–2384. doi: 10.1172/JCI117603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr MC, Hokanson JE, Deeb SS, Purnell JQ, Mitchell ES, Brunzell JD. A hepatic lipase gene promoter polymorphism attenuates the increase in hepatic lipase activity with increasing intra-abdominal fat in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2701–2707. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ordovas JM, Corella D, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Couture P, Coltell O, et al. Dietary fat intake determines the effect of a common polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene promoter on high-density lipoprotein metabolism: evidence of a strong dose effect in this gene-nutrient interaction in the Framingham Study. Circulation. 2002;106:2315–2321. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036597.52291.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riestra P, Lopez-Simon L, Ortega H, Gorgojo L, Martin-Moreno JM, Schoppen S, et al. Fat intake influences the effect of the hepatic lipase C-514T polymorphism on HDL-cholesterol levels in children. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:744–749. doi: 10.3181/0812-RM-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beer NL, Tribble ND, McCulloch LJ, Roos C, Johnson PR, Orho-Melander M, et al. The P446L variant in GCKR associated with fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels exerts its effect through increased glucokinase activity in liver. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4081–4088. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez-Martinez P, Delgado-Lista J, Garcia-Rios A, Mc Monagle J, Gulseth HL, Ordovas JM, et al. Glucokinase regulatory protein genetic variant interacts with omega-3 PUFA to influence insulin resistance and inflammation in metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nettleton JA, McKeown NM, Kanoni S, Lemaitre RN, Hivert MF, Ngwa J, et al. Interactions of dietary whole-grain intake with fasting glucose- and insulin-related genetic loci in individuals of European descent: a meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2684–2691. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellstrand S, Sonestedt E, Ericson U, Gullberg B, Wirfalt E, Hedblad B, et al. Intake levels of dietary long-chain PUFAs modify the association between genetic variation in FADS and LDL-C. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1183–1189. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P023721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, Burtt NP, de Bakker PI, Chen H, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Ryan DH, Johnson KC, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorin AA, Niemeier HM, Hogan P, Coday M, Davis C, DiLillo VG, et al. Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halder I, Kip KE, Mulukutla SR, Aiyer AN, Marroquin OC, Huggins GS, et al. Biogeographic ancestry, self-identified race, and admixture-phenotype associations in the Heart SCORE Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:146–155. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]