Abstract

Determining insular functional topography is essential for assessing autonomic consequences of neural injury. We examined that topography in the five major insular cortex gyri to three autonomic challenges, the Valsalva, hand grip, and foot cold pressor, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) procedures. Fifty-seven healthy subjects (age±std: 47±9 years) performed four 18 s Valsalva maneuvers (30 mmHg load pressure), four hand grip challenges (16 s at 80% effort), and a foot cold pressor (60 s, 4°C), with fMRI scans recorded every 2 s. Signal trends were compared across gyri using repeated measures ANOVA. Significantly (P<0.05) higher signals in left anterior versus posterior gyri appeared during Valsalva strain, and in the first 4 s of recovery. The right anterior gyri showed sustained higher signals up to 2 s post-challenge, relative to posterior gyri, with sub-gyral differentiation. Left anterior gyri signals were higher than posterior areas during the hand grip challenge. All right anterior gyri showed increased signals over posterior up to 12 s post-challenge, with decline in the most-anterior gyrus from 10–24 s during recovery. The left three anterior gyri showed relatively lower signals only during the 90 s recovery of the cold pressor, while the two most-anterior right gyri signals increased only during the stimulus. More-differentiated representation of autonomic signals appear in the anterior right insula for the Valsalva maneuver, a bilateral, more-posterior signal representation for hand grip, and preferentially right-sided, anterior-posterior representation for the cold pressor. The functional organization of the insular cortex is gyri-specific to unique autonomic challenges.

Keywords: Functional magnetic resonance imaging, autonomic nervous system, functional neuroanatomy, Valsalva maneuver, hand grip, cold pressor

INTRODUCTION

The insular cortex serves autonomic regulatory functions via projections to visceral, thalamic, brainstem and limbic areas, as indicated by rodent, primate and human studies (Allen et al., 1991; Cerliani et al., 2011; Jakab et al.; Mufson et al., 1984; Yasui et al., 1991). The insula receives input from multiple cortical areas involved with emotional, cognitive, and sensori-motor functions, many of which can trigger sympathetic and parasympathetic changes. However, the topographic organization for autonomic regulation of the human insula has only partially been outlined. An anterior-posterior organization for certain aspects of autonomic regulation is present both in rodents and humans (Goswami et al., 2011; Oppenheimer et al., 1990; Yasui et al., 1991), but functional boundaries in humans remain unclear. The human insular cortex shows consistent gyral subdivisions, and the anatomical and cellular distinctions of these subregions suggest that the functional neuroanatomy of autonomic control may also differ across gyri (Afif et al., 2008; Anderson et al., 2009; Naidich et al., 2004; Ture et al., 1999). The present study addresses the question of whether these gyri show distinct functional roles to different autonomic challenges.

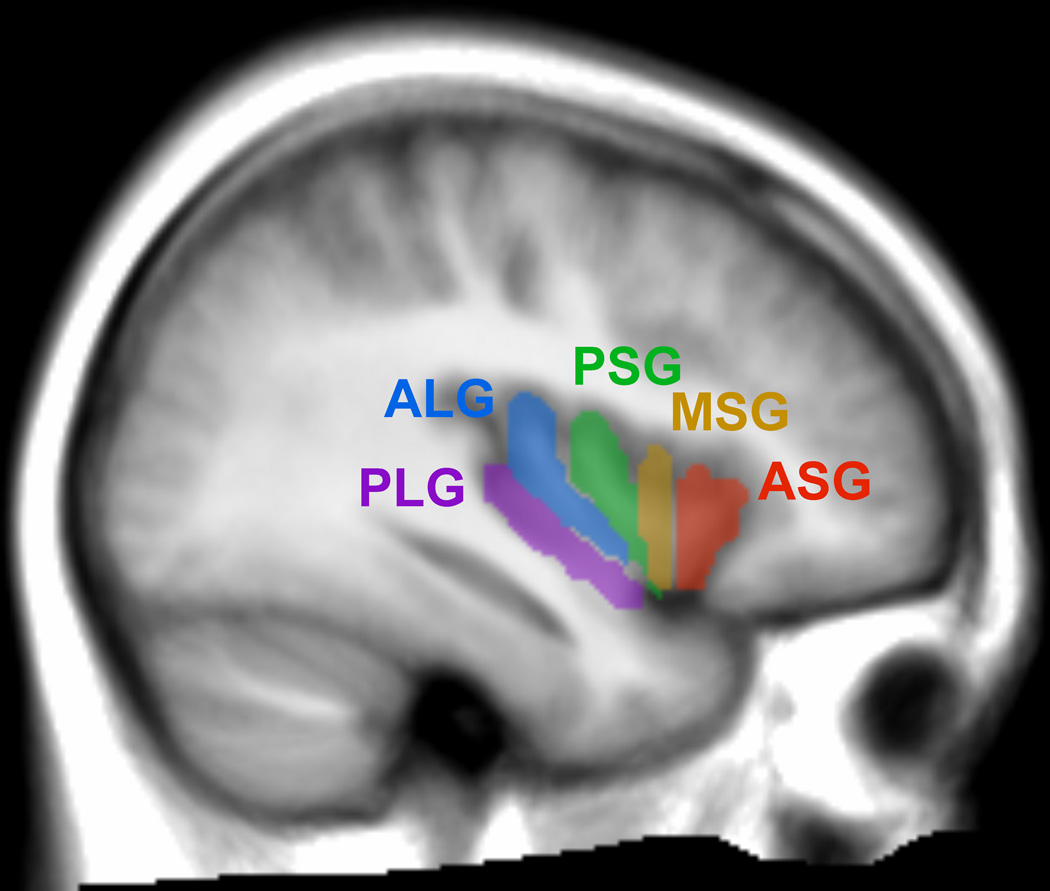

The human insular cortex usually contains five major gyri, with additional, smaller gyral areas in some subjects (Naidich et al., 2004; Ture et al., 1999). The major gyri lie in a dorsal-ventral orientation, with three anterior gyri referred to as the “short” gyri, and two posterior gyri termed the “long” gyri. The short gyri consist of the “anterior,” “mid,” and “posterior” short gyri (ASG, MSG and PSG, respectively; Fig. 1). A small minority of people do not have an MSG. Two additional minor gyri lie within the anterior insula, namely the transverse and accessory insular gyri. All five anterior gyri converge at the insular “apex,” the most-ventral portion of the superficial insular cortex (Naidich et al., 2004; Ture et al., 1999). The long gyri consist of the anterior and posterior long insular gyri (ALG and PLG, respectively). Both the cellular anatomy and connectivity differ across insular gyri (Anderson et al., 2009; Elston, 2002; Elston, 2003; Elston et al., 2005; Elston et al., 2002; Jacobs et al., 2001), supporting the concept of functional distinctions across these subregions.

Figure 1. Subregions of the anterior and posterior insular cortex.

The PLG, ALG, PSG, MSG, and ASG are shown overlaid on the average of 57 healthy control subjects’ anatomical scans (normalized to MNI space, left side, sagittal slice at −38 mm).

Imaging and stroke studies in humans confirm lateralized and anterior-posterior functional organization in the insular cortices. The right anterior insular cortex, which encompasses the three short gyri, shows functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signal increases to sympathetic challenges (King et al., 1999; Wong et al., 2007). Other functions also show localization; a somatotopic organization for sensory processing exists over the insula with projections to neighboring areas (Bjornsdotter et al., 2009; Mazzola et al., 2009), and some forms of pain representation lie principally within MSG (Afif et al., 2008), although the dorsal posterior insula is responsive to cold and other temperature stimuli, with a somatotopic representation (Brooks et al., 2005; Craig et al., 2000; Henderson et al., 2007; Hua le et al., 2005; Maihofner et al., 2002). However, these human studies have not resolved the topography of function to the level of gyri.

Refining our knowledge of the functional organization within the insula would benefit understanding of autonomic control circuitry, as well as help with clinical interpretation of the consequences of damage in insular subregions. Initially, the pathology of principal concern was stroke (Oppenheimer, 1993; Oppenheimer et al., 1992b; Oppenheimer et al., 1996), but the revelation of significant insular injury in heart failure (Woo et al., 2003) and obstructive sleep apnea (Macey et al., 2008) mandate clarification of topographical organization of function. Our objective was to evaluate differences in neural responses across the gyri of the left and right insular cortices to autonomic stimuli, the Valsalva maneuver, hand grip, and cold pressor (Denq et al., 1998; Mancia et al., 1978; Victor et al., 1987), using fMRI. These three autonomic challenges elicit autonomic responses in conjunction with differing sensory stimuli and volitional action. The Valsalva maneuver consists of both a sympathetic and parasympathetic component, whereas the hand grip is a voluntarily-initiated, non-painful sympathetic challenge, and the cold pressor challenge is a sensory-initiated sympathetic challenge with a minor pain component.

METHODS

Subjects

We studied 57 healthy adults (age ± std: 47.0 ± 9.1 years, range: 31–66 years; 37 males, 20 females). Subjects did not have a history of cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarctions, heart failure, neurological disorders, or mental illness, and were not taking cardiovascular or psychotropic medications. Subjects were recruited from the general Los Angeles area, and did not weigh more than 125 kg or have any metallic or electronic implants; the latter two issues are MRI scanner contraindications. All subjects provided informed consent in writing, and the research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UCLA.

Valsalva Maneuver

The Valsalva maneuver, a common test of autonomic function (Taylor, 1996), was performed in a sequence of four 18 s exhalations against a closed glottis, spaced one minute apart, incurring a target intra-thoracic pressure of 30 mmHg (Taylor, 1996). The challenge elicits a sequence of sympathetic and parasympathetic responses, which are accompanied by a pattern of heart rate and blood pressure changes corresponding to adaptations to thoracic and cardiovascular sequelae introduced by the maneuver (Denq et al., 1998; Taylor, 1996). A light signal was used to indicate onset of the challenge for the Valsalva effort to the subject. Upon seeing the light signal, subjects were instructed to take a breath and exhale against a resistance, maintaining a target pressure. A second light was illuminated when the subject achieved 30 mmHg pressure. Subjects practiced the Valsalva maneuver prior to scanning.

Hand Grip

The static hand grip is a voluntarily-initiated autonomic challenge that elicits increased heart rate and sympathetic muscle outflow (Mancia et al., 1978; Mark et al., 1985). The test involved squeezing an MR-compatible pressurized bag connected to a pressure sensor with instructions to maintain a short (16 s) test at a subjective 80% of maximum grip strength. Four repeated tests were performed, with an initial baseline of 100 s preceding the first test, and subsequent hand grip periods separated by 1 min, and terminated with a 100 s recovery period. Subjects practiced the hand grip prior to scanning.

Cold Pressor

The cold pressor challenge involved immersing the right foot up to the ankle in cold water (4 °C) for a 1 min period, preceded by a 2 min baseline, and followed by a 2 min recovery period. Two investigators lifted the foot into a basin with cold water that covered the ankle at the start of the challenge, and removed it 60 s later. Each movement lasted less than 4 s (2 fMRI volumes), and signal artifact was present during periods of movement. The task elicits an increase in sympathetic activity and blood pressure, and pain if near-freezing water is used (Victor et al., 1987). The subjects reported moderate levels of pain at the 4 °C temperature.

Physiologic Signals

Cardiac, load pressure and indicator signals (e.g., light on/off) were recorded with an analog-to-digital acquisition system (instruNet INET-100B, GWI Instruments, Inc., Somerville, MA). Heart rate was assessed using an MRI-compatible pulse oximeter (Nonin Medical Inc., Plymouth, MN). The sensor was placed on the right index finger throughout the scan, and heart rate was calculated from the raw oximetry signal acquired at 1 kHz using custom peak-detection software followed by expert review. Expiratory pressure was measured via tubing connected to a pressure sensor (Omega Engineering Inc., Stamford, CT) outside the scanner. Patient cue signals were simultaneously recorded. Signals were aligned to the MRI scans, and data corresponding to the fMRI signals extracted.

MRI Scanning

Functional MRI scans were acquired using a 3.0 Tesla scanner (Siemens Magneton Tim-Trio, Erlangen, Germany) while subjects lay supine. A foam pad was placed on either side of the head to minimize movement. We collected whole-brain images with the blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) contrast every two seconds (repetition time [TR] = 2000 ms; echo time [TE] = 30 ms; flip angle = 90°; matrix size 64 × 64; field-of-view 220 × 220 mm; slice thickness = 4.5 mm). Two high resolution, T1-weighted anatomical images were also acquired with a magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence (TR = 2200 ms; TE = 2.2 ms; inversion time = 900 ms; flip angle = 9°; matrix size 256 × 256; field-of-view 230 × 230 mm; slice thickness = 1.0 mm). Field map data consisting of phase and magnitude images were collected using the standard Siemens protocol, to allow for correction of distortions due to field inhomogeneities.

MRI Data Preprocessing

All anatomical scans were inspected to ensure the absence of visible pathology. For each fMRI series, the global signal was calculated and the images realigned to account for head motion. Subjects with large changes in global BOLD signal, or who moved more than 4 mm in any direction were not included in the study. Each fMRI series was linearly detrended to account for signal drift (but not global effects), and corrected for field inhomogeneities (Hutton et al., 2002), spatially normalized, and smoothed (8 mm Gaussian filter), and mean time trends from each voxel were calculated across all subjects, as well as the challenge-means across each of the four Valsalva and hand grip periods (the cold pressor only had one repeat and so was not averaged). A mean image of all subjects’ spatially normalized, anatomic scans was created. Software used included the statistical parametric mapping package, SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, UK; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), MRIcron (Rorden et al., 2007), and MATLAB-based custom software.

Region of Interest (ROI) Tracing

The five major gyral regions in the insular cortex, the ASG, MSG, PSG, ALG and PLG, were outlined on the mean anatomical image with MRIcron software, using the anatomical descriptions by Ture et al. and Naidich et al. (Naidich et al., 2004; Ture et al., 1999), as shown in Figure 1. The three main gyri of the anterior insula, the ASG, MSG, and PSG, make up the convex surface of the structure, and are visible on the sagittal and axial views of the mean anatomical image. The accessory and transverse gyri, two other gyri in the anterior insula, are difficult to visualize (Naidich et al., 2004), and were not visible on the mean anatomical image. Thus, in our tracing of the ASG, we included the entire most-anterior portion of the insula, which included the accessory and transverse gyri. The posterior gyri (ALG and PLG) were easily visible on sagittal as well as axial sections of the anatomical volume.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated measures ANOVA (RMANOVA), implemented with the mixed linear model procedure “proc mixed” in SAS software (Littell et al., 1996), was used to identify periods of significant response relative to baseline, during the Valsalva, hand grip, and cold pressor periods and subsequent recovery. We modeled the fMRI responses as a function of scan period. Significance was first assessed at the global level (P < 0.05), as per the Tukey-Fisher criterion for multiple comparisons; for significant models, the time-points of significant responses were identified. To avoid potential confounds due to global vascular effects, we focused on relative changes between gyri, and present graphical visualizations with respect to the PLG, as the posterior insula typically responds less than anterior regions in response to autonomic stimuli (King et al., 1999). The restriction of only assessing differences rather than absolute responses results from the inherent relative nature of the BOLD-based fMRI technique.

RESULTS

Heart Rate Responses

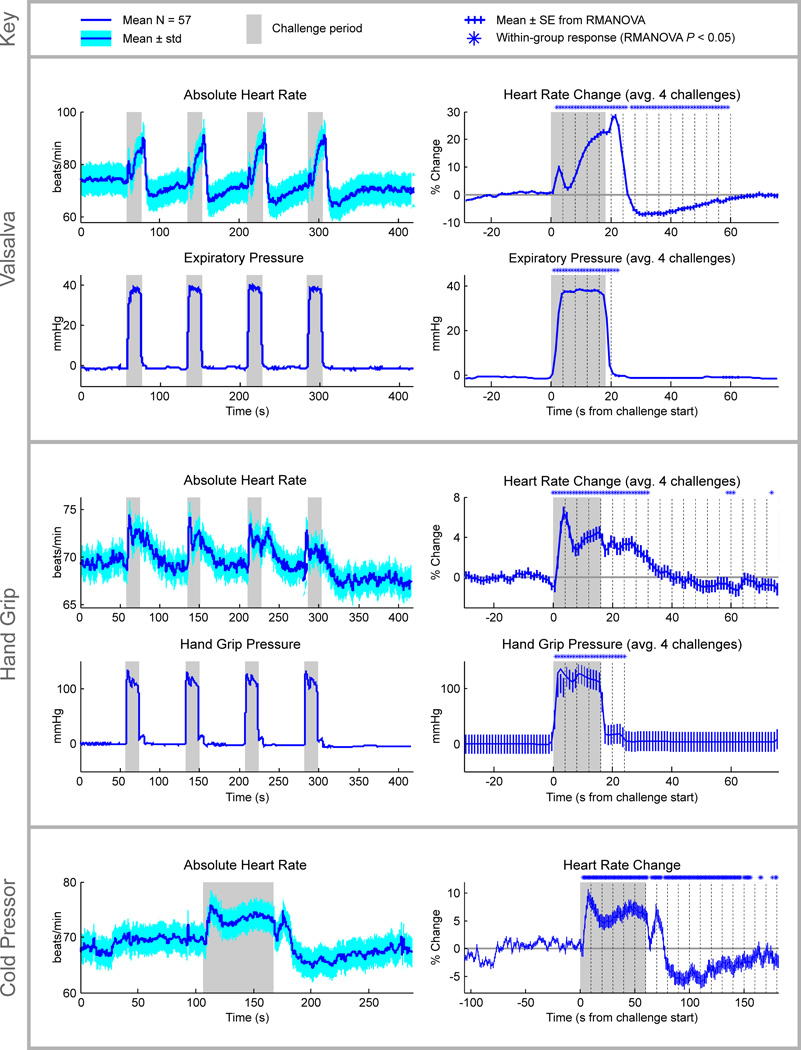

The heart rate patterns to the different challenges are shown in Figure 2, with heart rate showing significant changes during and after all three tasks (RMANOVA, P < 0.05; time-points of significant change relative to baseline indication above right-hand graphs in Figure 2). Transient heart rate increases appeared in the initial phase of the Valsalva maneuver, followed by a steady rise in the second phase, then a third transient increase upon release of strain, followed by a decline below baseline, and a slow return to baseline. The hand grip elicited an initial heart rate spike, peaking at 5 s into the task, followed by a sustained elevated heart rate, which upon release, gradually returned to baseline. The cold pressor response showed a sustained heart rate increase, with an undershoot and gradual return to baseline following removal of the cold stimulus.

Figure 2. Physiologic responses to autonomic challenges.

Heart rate responses to the autonomic challenges are shown across the series and averaged over repeated challenges (Valsalva and hand grip) with time-points of significance response from baseline denoted above the right-hand traces (RMANOVA, P < 0.05; key at top). Grey shading denotes challenge periods. Mean heart rates are shown for each challenge, and for the Valsalva maneuver, expiratory pressure is also shown, and for hand grip pressure, change from rest is shown.

fMRI Responses

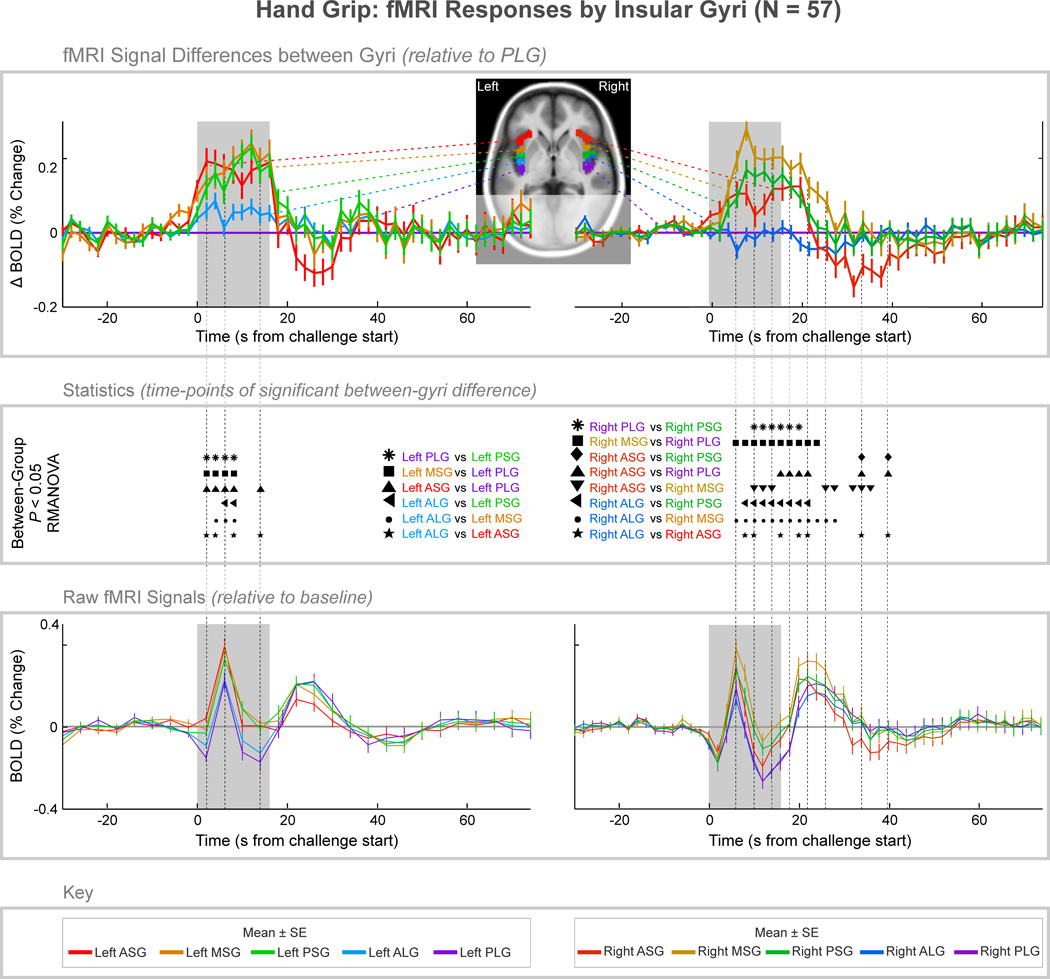

All three challenges elicited fMRI signal responses that differed between gyri (Figs. 3–5; mean values in Tables 1–3 of the supplementary materials). The signal differences in the top graphs of each figure illustrate a general pattern of higher activity in the anterior, relative to the posterior gyri. Left and right differences are shown for the only non-lateralized challenge, the Valsalva maneuver (Fig. 6). A synthesis of the major findings is shown in Table 1, with in-depth descriptions below.

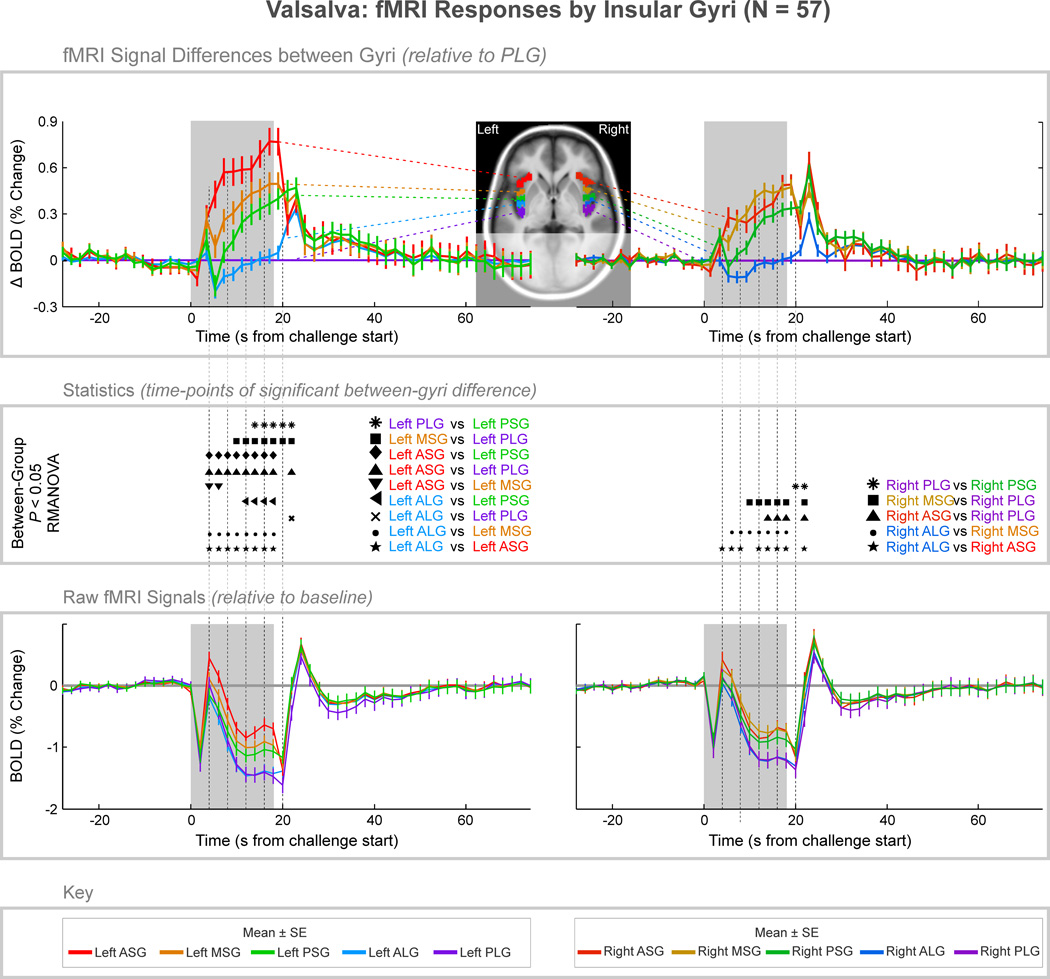

Figure 3. fMRI signal responses across insular cortex gyri, averaged over four 18-second Valsalva maneuvers in 57 subjects.

The top graphs illustrate signal differences between gyri, relative to the PLG. The middle section illustrates time-points of statistically significant differences between gyri (P < 0.05, RMANOVA), and the bottom graph illustrates the raw signals ± SE relative to baseline (the overall raw signal patterns relate to global effects primarily due to changes in cerebral blood volume). Mean values are reported in Table 1 of the supplementary material.

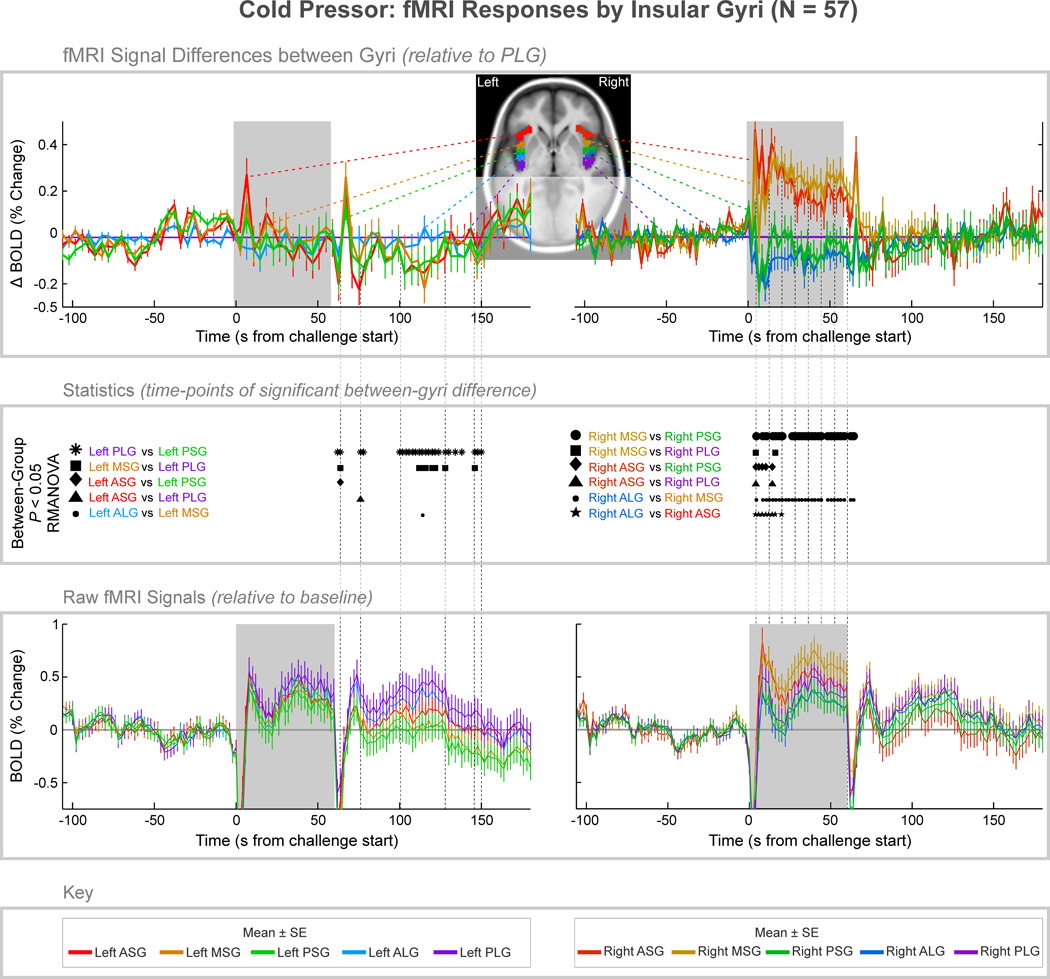

Figure 5. fMRI signal responses across insular cortex gyri, averaged over one 60 second cold pressor challenge in 57 subjects.

The top graphs illustrate signal difference between gyri, relative to the PLG. The middle section illustrates time-points of statistically significant difference between gyri (P < 0.05, RMANOVA), and the bottom graph illustrates the raw signals relative to baseline (the overall raw signal patterns relate to global effects primarily due to changes in cerebral blood volume). Mean values are reported in Table 3 of the supplementary material.

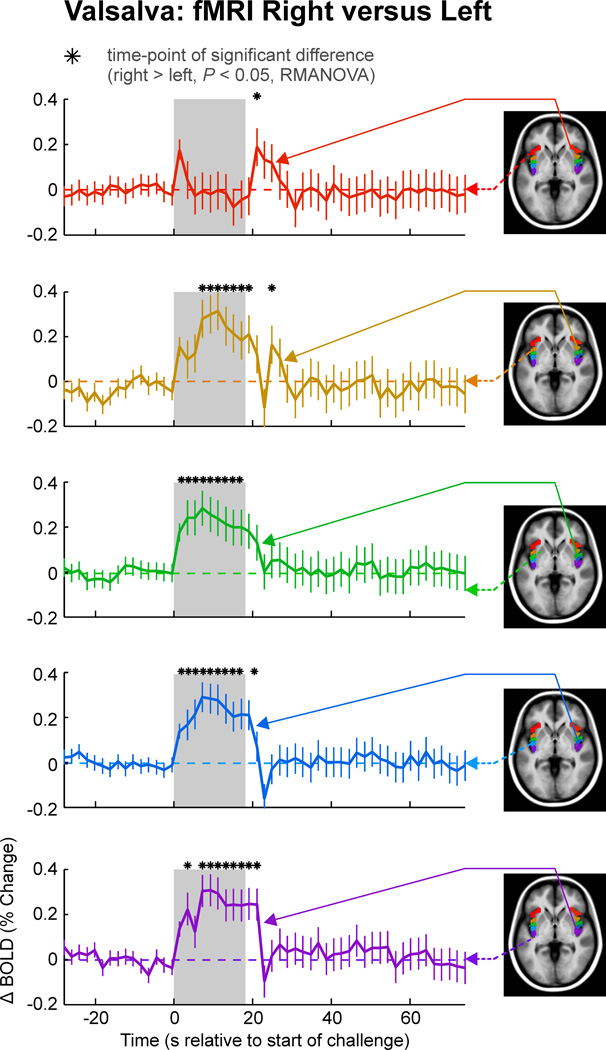

Figure 6. Lateralization of Valsalva BOLD responses.

The fMRI BOLD responses (mean ± SE, N = 57) to the Valsalva are shown on the right relative to the left side for each gyri, with all right gyri showing predominantly higher signals on the right over the left (P < 0.05, RMANOVA; “*”indicates time points of significant difference). The ASG has transiently higher signals, whereas the other four gyri showed sustained increases on right over left sides during the challenge period

Table 1.

Simplified representation of direction of differences in gyral signal responses during and after challenges.

| Valsalva Task |

Recovery | Hand grip Task |

Recovery | Cold pressor Task |

Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | ASG > MSG > PSG > LG |

- | ASG+MSG+PSG >LG |

- | - | LG > ASG > MSG+PSG |

| Right | ASG+MSG > PSG > LG |

- | MSG+PSG > ASG > LG |

MSG+PSG+LG > ASG |

ASG+MSG > PSG+LG |

- |

ASG: anterior short gyrus; MSG: middle short gyrus; PSG: posterior short gyrus; LG: long gyri, including anterior long gyrus and posterior long gyrus.

Valsalva maneuver

Significant fMRI signal differences emerged between gyri in both left and right insulae during the second phase of the Valsalva (Fig. 3). In the left insula, the ASG showed an elevated response relative to other gyri throughout the strain period (time 4–18 s), with the MSG also showing a sustained, higher response relative to more posterior gyri, as did the PSG, relative to the ALG and PLG (e.g., at 16 s into the challenge, ASG > MSG by 0.27%, MSG > PSG by 0.14%, and PSG > PLG by 0.36%; Table 1 of supplementary material). Upon release (Phase III), the ALG showed a briefly higher response than the PLG (20 s), followed by a return toward baseline by all gyri. The right insula showed matching responses in the ASG and MSG, which were also similar to those in the PSG. All right short gyri showed sustained higher signals relative to the long gyri.

Signals in all gyri were greater on the right than the left during the strain phase (Fig. 6). The right ASG showed a transient higher signal at onset of the maneuver (Phase I, time 0–4 s), whereas responses in all other gyri were higher throughout the later strain period (phase II, time 6–18 s), with peak differences at 8 s (PSG, 0.26% higher on right; PLG, 0.31% higher) and 10 s (MSG, 0.32% higher; ALG, 0.29% higher).

Hand grip challenge

Signal differences appeared between gyri during and after the hand grip challenge in the ipsilateral challenge (right) insula, but in the left insula, differences in activation between gyri only appeared during the challenge, and primarily during the initial 8 s (Fig. 4). The left insular responses showed distinct patterns in the short and long gyri, with significant differences between the short gyri and the long gyri, but no differences amongst short or long gyri. The maximum relative amplitude difference was at 12 s after challenge onset between the MSG and PLG (MSG – PLG = 0.24%). In the right insula, the short gyri each showed differences relative to the long gyri. However, unlike the left side, the MSG response was significantly higher than in the ASG, with the greatest amplitude difference at 8 s (MSG – ASG = 0.17%). That time point also showed the greatest difference between long and short gyri (MSG – PLG = 0.29%, time = 8 s). The short/long differences persisted for 12 s (time = 28 s) after release, and the MSG – ASG differences continued until 24 s (time = 40 s) after the end of the challenge, with the ASG showing an undershoot relative to all four other gyri.

Figure 4. fMRI signal responses across insular cortex gyri, averaged over four 16-second hand grip challenges in 57 subjects.

The top graphs illustrate signal difference between gyri, relative to the PLG. The middle section illustrates time-points of statistically significant difference between gyri (P < 0.05, RMANOVA), and the bottom graph illustrates the raw signals relative to baseline (the overall raw signal patterns relate to global effects primarily due to changes in cerebral blood volume). Mean values are reported in Table 2 of the supplementary material.

Cold pressor challenge

In the ipsilateral-to-challenge (right) insula, BOLD fMRI differences appeared between gyri solely during the foot cold pressor challenge, while fMRI differences in the left insula appeared only after the challenge (Fig. 5; Table 3 of supplementary material). In the right side, the two anterior-most gyri (ASG and MSG) increased in a similar pattern, relative to the three more-posterior gyri (PSG, ALG and PLG). The maximum difference was at 14 s (ASG – ALG = 0.51%), with maximum differences between the ASG/MSG and other gyri of approximately 0.3% and higher throughout the challenge (time 4 s to 58 s). The left insula showed similar patterns across gyri during the cold pressor stimulus, with relative declines in the anterior relative to the posterior gyri occurring up to 90 s after the challenge (time 150 s). From 56 s after the end of the cold pressor (time 116 s), the MSG and PSG showed a significantly lower signal relative to the other gyri. The greatest difference was 14 s after the removal of the stimulus (time = 74 s, PLG – ASG = 0.23%).

DISCUSSION

The insular cortices showed unique responses to different autonomic challenges between anterior and posterior gyri, and between left and right insulae, indicating that functional organization of processing related to autonomic challenges differs between gyri. The anterior insular gyri were most responsive during the challenge periods of all tasks, whereas the two posterior gyri (ALG and PLG) responded similarly during all tasks, and always with similar, or lower magnitude than the anterior gyral patterns. A remarkable characteristic was the large transient onset and offset patterns to cold and Valsalva challenges, principally in anterior gyri to cold, but in both anterior and posterior gyri in Valsalva maneuvers. Signal patterns during recovery periods also help differentiate gyral responses. These findings are consistent with existing literature showing that the anterior portion of the insular cortex principally serves sympathetic regulation; however, the data extend previous findings by demonstrating that functional representation of signals to autonomic challenges differs across the individual insular gyri.

Valsalva

Responses in both the right and left insular cortices during the strain phase of the Valsalva maneuver differed between gyri in an anterior-posterior order, with greater responses in the anterior gyri. This phase is characterized by a large and rapid increase in sympathetic activity, as reflected in the heart rate increase; thus, the finding confirms the anterior location of autonomic control within the insula. However, while on the right side, all anterior gyri (ASG, MSG and PSG) responded similarly, on the left side the activity was greatest in the ASG, followed by the MSG, which was greater than the PSG. Given the preferential left-sided parasympathetic dominance (Oppenheimer et al., 1990), this finding suggests that sympathetic regulation on the left insula is greatest in the most-anterior gyri (ASG), whereas the regulation is similar across all three anterior gyri on the right side.

Hand grip challenge

The strain phase of the hand grip challenge, which is associated with moderate sympathetic activity as reflected in the heart rate increase, elicited the greatest responses in the MSG and PSG. On the left side, the ASG showed similar increases, whereas on the right the ASG increases were less than the MSG and PSG. The findings likely reflect the motor as well as autonomic components of the task. In a meta-analysis of 1768 studies, including functional imaging experiments, motor function was predominately found in the PSG (Bamiou et al., 2003; Kurth et al., 2010), which is consistent with the greater responses in the PSG over ASG in the present study. Since the sympathetic increase during hand grip is moderate (relative to during the Valsalva maneuver), contributions to the ASG responses related to sympathetic activation may have been dominated by the motor components. The MSG followed the same patterns as the PSG on left and right sides, suggesting motor roles for that area.

Cold Pressor

The left ASG showed increased activation during only the initial period of the cold pressor challenge, possibly suggesting an initial novel sensory processing role, or possibly the anticipation of pain (Ploghaus et al., 1999). The trend toward declining signals relative to the PLG may reflect an increase in that area relative to other gyri, reflecting the right-foot temperature and nocioceptive stimulation (Brooks et al., 2005; Craig et al., 2000; Henderson et al., 2007; Henderson et al., 2010; Henderson et al., 2011; Hua le et al., 2005). This possibility is consistent with the raw signal pattern (bottom of Fig. 5) showing a signal increase across all gyri on the contralateral side. The right-sided increases in the anterior gyri (ASG and MSG) presumably reflect sympathetic activation, which is not seen in the PSG. As with the left side, the ASG initially rose to a peak before falling towards baseline throughout the one minute challenge period, perhaps reflecting a gradual adaptation to the new state. The uniformly-elevated MSG signal is consistent with the pain aspect of the task (Afif et al., 2008; Brooks et al., 2005; Henderson et al., 2011). Thus, the cold pressor findings support a right ASG role in sympathetic activity, a right MSG role in pain synthesis, and a left posterior insula role in sensory integration.

Lateralization of function across insula gyri

The sympathetic phase of the Valsalva was accompanied by higher right than left insular fMRI signals (Fig. 6), consistent with a preferential role for sympathetic integration on that side. Lateralization of fMRI responses during the Valsalva maneuver appeared across all gyri during phase II with sustained differences between the right and left insulae appearing throughout the Valsalva breath hold in all gyri, except the ASG which showed only transiently higher signals at the onset and offset of the challenge Such lateralization is consistent with findings in rats and humans (Oppenheimer et al., 1990; Oppenheimer et al., 1992a; Oppenheimer et al., 1992b; Oppenheimer et al., 1996; Oppenheimer et al., 1991). In resting-state fMRI studies, the right anterior insula also has stronger functional connectivity with autonomic regions, such as the brainstem, pons, and right thalamus, whereas left anterior regions do not show connectivity with the thalamus at all (Cauda et al., 2011). The more prominent sympathetic role of the right insula likely reflects those structural connections to autonomic control areas.

Asymmetry in the cold pressor and hand grip challenges could not be directly evaluated, since the cold pressor challenge was only applied to the right foot, and the hand grip performed only by the right hand.

Considerations

Resolution of the fMRI scans in this study was limited to voxel sizes of 3.4 3.4 4.5 mm. For group data, additional resolution limitations developed from normalizing images of all subjects to a common space. By convention, normalized fMRI data were smoothed with an 8 mm kernel filter. The principal consequence of the low resolution is a partial volume effect, whereby signals classified as originating from a single gyri will contain some signal from neighboring regions. Such effects would tend to blur differences, which reinforces the findings that the differences here are likely to be robust.

Cerebral blood flow and resting cerebral blood volume vary across brain regions (Kastrup et al., 1999; Rostrup et al., 2000). Biophysical models of the BOLD signal indicate that multiple hemodynamic factors not related to neuronal activation can influence the BOLD response, including hematocrit, resting blood volume, and other factors (Bandettini et al., 1997; Boxerman et al., 1995; Ogawa et al., 1993). However, the differential BOLD responses between left and right gyri and lateralization of insula function are unlikely to be an artifact of these hemodynamic factors, since each gyrus has similar vasculature on the left and right sides (Ture et al., 1999; Varnavas et al., 1999), and we noted significantly different patterns of activation on each side. However, vascular influences on the lateralization of responses cannot be completely ruled out, given the presence of differences in left and right vascularization.

Another consideration is that gyral functions likely further divide along inferior and superior directions (Cerf-Ducastel et al., 2001). Investigating inferior/superior functional topography would be a logical next step from the present study. However, one difficulty is the identification of anatomical boundaries, which are not as clear as the gyral distinctions; thus, the method here of tracing over the average of all subjects’ anatomical images would likely need to be altered, depending upon what details could be resolved with available scans.

Conclusions

The insular cortices show functional differentiation between anterior and posterior gyri during Valsalva maneuver, hand grip, and cold pressor autonomic challenges, with significant laterality differences in the Valsalva maneuver. Large onset and offset transient responses appeared to the cold pressor and Valsalva maneuver challenges, and gyri differed on recovery periods in particular challenges. Posterior and anterior gyri differed in lateralization patterns during the Valsalva maneuver, and anterior gyri showed significantly different responses to the sympathetic-dominant phase of the Valsalva maneuver, and anterior-posterior differences were noted during the hand grip challenge. The insular gyri are useful anatomical markers of functional boundaries related to autonomic processing. Assessing fMRI responses or the impact of neural injury within specific gyri may help refine our understanding of the impaired physiology in certain disease conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support for PW of the UCLA Howard Hughes Undergraduate Research and UCLA Undergraduate Research Fellowship Programs.

GRANTS

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health, NR-011230 (PMM), HD-22695 (RMH) and NR-009116 (MAW).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- Afif A, Hoffmann D, Minotti L, Benabid AL, Kahane P. Middle short gyrus of the insula implicated in pain processing. Pain. 2008;138:546–555. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GV, Saper CB, Hurley KM, Cechetto DF. Organization of visceral and limbic connections in the insular cortex of the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1991;311:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.903110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Bones B, Robinson B, Hass C, Lee H, Ford K, Roberts TA, Jacobs B. The morphology of supragranular pyramidal neurons in the human insular cortex: a quantitative Golgi study. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:2131–2144. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamiou DE, Musiek FE, Luxon LM. The insula (Island of Reil) and its role in auditory processing. Literature review. Brain research. Brain research reviews. 2003;42:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandettini PA, Wong EC. A hypercapnia-based normalization method for improved spatial localization of human brain activation with fMRI. NMR in biomedicine. 1997;10:197–203. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199706/08)10:4/5<197::aid-nbm466>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsdotter M, Loken L, Olausson H, Vallbo A, Wessberg J. Somatotopic organization of gentle touch processing in the posterior insular cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:9314–9320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0400-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxerman JL, Bandettini PA, Kwong KK, Baker JR, Davis TL, Rosen BR, Weisskoff RM. The intravascular contribution to fMRI signal change: Monte Carlo modeling and diffusion-weighted studies in vivo. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:4–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JC, Zambreanu L, Godinez A, Craig AD, Tracey I. Somatotopic organisation of the human insula to painful heat studied with high resolution functional imaging. NeuroImage. 2005;27:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, D'Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Geminiani G, Vercelli A. Functional connectivity of the insula in the resting brain. NeuroImage. 2011;55:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerf-Ducastel B, Van de Moortele PF, MacLeod P, Le Bihan D, Faurion A. Interaction of gustatory and lingual somatosensory perceptions at the cortical level in the human: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Chem Senses. 2001;26:371–383. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerliani L, Thomas RM, Jbabdi S, Siero JC, Nanetti L, Crippa A, Gazzola V, D'Arceuil H, Keysers C. Probabilistic tractography recovers a rostrocaudal trajectory of connectivity variability in the human insular cortex. Human brain mapping. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hbm.21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, Chen K, Bandy D, Reiman EM. Thermosensory activation of insular cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2000;3:184–190. doi: 10.1038/72131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denq JC, O'Brien PC, Low PA. Normative data on phases of the Valsalva maneuver. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;15:535–540. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN. Cortical heterogeneity: implications for visual processing and polysensory integration. Journal of Neurocytology. 2002;31:317–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1024182228103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN. Cortex, cognition and the cell: new insights into the pyramidal neuron and prefrontal function. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13:1124–1138. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN, Benavides-Piccione R, Elston A, Defelipe J, Manger PR. Specialization in pyramidal cell structure in the sensory-motor cortex of the vervet monkey (Cercopethicus pygerythrus) Neuroscience. 2005;134:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston GN, Rockland KS. The pyramidal cell of the sensorimotor cortex of the macaque monkey: phenotypic variation. Cerebral Cortex. 2002;12:1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R, Frances MF, Shoemaker JK. Representation of somatosensory inputs within the cortical autonomic network. NeuroImage. 2011;54:1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LA, Gandevia SC, Macefield VG. Somatotopic organization of the processing of muscle and cutaneous pain in the left and right insula cortex: a single-trial fMRI study. Pain. 2007;128:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LA, Rubin TK, Macefield VG. Within-limb somatotopic representation of acute muscle pain in the human contralateral dorsal posterior insula. Human brain mapping. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hbm.21131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LA, Rubin TK, Macefield VG. Within-limb somatotopic representation of acute muscle pain in the human contralateral dorsal posterior insula. Human brain mapping. 2011;32:1592–1601. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua le H, Strigo IA, Baxter LC, Johnson SC, Craig AD. Anteroposterior somatotopy of innocuous cooling activation focus in human dorsal posterior insular cortex. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2005;289:R319–R325. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00123.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton C, Bork A, Josephs O, Deichmann R, Ashburner J, Turner R. Image distortion correction in fMRI: A quantitative evaluation. NeuroImage. 2002;16:217–240. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs B, Schall M, Prather M, Kapler E, Driscoll L, Baca S, Jacobs J, Ford K, Wainwright M, Treml M. Regional dendritic and spine variation in human cerebral cortex: a quantitative golgi study. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:558–571. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab A, Molnár P, Bogner P, Béres M, Berényi E. Connectivity-based parcellation reveals interhemispheric differences in the insula. Brain Topography. :1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10548-011-0205-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup A, Li TQ, Glover GH, Moseley ME. Cerebral blood flow-related signal changes during breath-holding. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1233–1238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AB, Menon RS, Hachinski V, Cechetto DF. Human forebrain activation by visceral stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:572–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:519–534. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Macey PM, Kumar R, Woo MA, Valladares EM, Yan-Go FL, Harper RM. Brain structural changes in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2008;31:967–977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihofner C, Kaltenhauser M, Neundorfer B, Lang E. Temporo-spatial analysis of cortical activation by phasic innocuous and noxious cold stimuli--a magnetoencephalographic study. Pain. 2002;100:281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Iannos J, Jamieson GG, Lawrence RH, Sharman PR, Ludbrook J. Effect of isometric hand-grip exercise on the carotid sinus baroreceptor reflex in man. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1978;54:33–37. doi: 10.1042/cs0540033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark AL, Victor RG, Nerhed C, Wallin BG. Microneurographic studies of the mechanisms of sympathetic nerve responses to static exercise in humans. Circulation research. 1985;57:461–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola L, Isnard J, Peyron R, Guenot M, Mauguiere F. Somatotopic organization of pain responses to direct electrical stimulation of the human insular cortex. Pain. 2009;146:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson EJ, Mesulam MM. Thalamic connections of the insula in the rhesus monkey and comments on the paralimbic connectivity of the medial pulvinar nucleus. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1984;227:109–120. doi: 10.1002/cne.902270112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidich TP, Kang E, Fatterpekar GM, Delman BN, Gultekin SH, Wolfe D, Ortiz O, Yousry I, Weismann M, Yousry TA. The insula: anatomic study and MR imaging display at 1.5 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:222–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ellermann JM, Ugurbil K. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J. 1993;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer S. The anatomy and physiology of cortical mechanisms of cardiac control. Stroke. 1993;24:I3–I5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SM, Cechetto DF. Cardiac chronotropic organization of the rat insular cortex. Brain Res. 1990;533:66–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91796-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SM, Gelb A, Girvin JP, Hachinski VC. Cardiovascular effects of human insular cortex stimulation. Neurology. 1992a;42:1727–1732. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SM, Hachinski VC. The cardiac consequences of stroke. Neurol Clin. 1992b;10:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SM, Kedem G, Martin WM. Left-insular cortex lesions perturb cardiac autonomic tone in humans. Clin Auton Res. 1996;6:131–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02281899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SM, Wilson JX, Guiraudon C, Cechetto DF. Insular cortex stimulation produces lethal cardiac arrhythmias: a mechanism of sudden death? Brain Res. 1991;550:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90412-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Tracey I, Gati JS, Clare S, Menon RS, Matthews PM, Rawlins JN. Science. Vol. 284. New York, N.Y: 1999. Dissociating pain from its anticipation in the human brain; pp. 1979–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Karnath HO, Bonilha L. Improving lesion-symptom mapping. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:1081–1088. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.7.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostrup E, Law I, Blinkenberg M, Larsson HB, Born AP, Holm S, Paulson OB. Regional differences in the CBF and BOLD responses to hypercapnia: a combined PET and fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2000;11:87–97. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. The Valsalva Manoeuvre: A Critical Review. Vol. 26. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society; 1996. pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ture U, Yasargil DC, Al-Mefty O, Yasargil MG. Topographic anatomy of the insular region. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:720–733. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.4.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnavas GG, Grand W. The insular cortex: morphological and vascular anatomic characteristics. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:127–136. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199901000-00079. discussion 136-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Leimbach WN, Jr, Seals DR, Wallin BG, Mark AL. Effects of the cold pressor test on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Hypertension. 1987;9:429–436. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SW, Kimmerly DS, Masse N, Menon RS, Cechetto DF, Shoemaker JK. Sex differences in forebrain and cardiovagal responses at the onset of isometric handgrip exercise: a retrospective fMRI study. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1402–1411. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00171.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo MA, Macey PM, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, Harper RM. Regional brain gray matter loss in heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:677–684. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00101.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y, Breder CD, Saper CB, Cechetto DF. Autonomic responses and efferent pathways from the insular cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;303:355–374. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.