Abstract

To prepare a novel Bispecific Antibody (BsAb) as a potential targeted therapy for T1D, we produced a “functionally inert” monoclonal antibody (mAb) against Glucose transporter-2 (GLUT-2) expressed on β-cells to serve as an anchoring antibody. The therapeutic arm is an agonistic mAb against Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA-4), a negative regulator of T-cell activation expressed on activated CD4+ T-cells. A BsAb was prepared by chemically coupling an anti-GLUT2 mAb to an agonistic anti-CTLA-4 mAb. This BsAb was able to bind to GLUT2 and CTLA-4 in vitro, and to pancreatic islets, both in vitro and in vivo. We tested the safety and efficacy of this BsAb by treating Non-Obese Diabetes (NOD) mice and found that it could delay the onset of diabetes with no apparent undesirable side effects. Thus, engagement of CTLA-4 on activated T cells from target tissue can be an effective way to treat type-1 diabetes.

Keywords: anti-CTLA-4, anti-Glut2, dendritic cells, regulatory T cells, diabetes, tolerance

1. INTRODUCTION

Type-1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) is a T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease characterized by the destruction of pancreatic β-cells by autoreactive T cells, resulting in absolute dependence on exogenous insulin for survival and maintenance of health. [1–4]. Immune regulation, including antigen presentation and regulatory T cell (Treg) function, is defective in T1D [4–10]. Although immunosuppressive drugs are used to treat autoimmune diseases, such therapies are partially effective and not curative [11, 12]; and result in global attenuation of the immune response thus enhancing susceptibility to opportunistic infections and cancers [13–15]. Therefore, the induction of β-cell Ag specific T-cell tolerance to prevent disease development in patients at risk of developing, or with newly onset, diabetes is highly desired [16, 17].

Activation of T cells results in increased expression of the T-cell surface molecule CTLA-4 that shares homology with CD28 [6, 18, 19]. CTLA-4 has a higher affinity for B7 (i.e. CD80 and CD86) ligands than CD28 and thus competes for binding to B7 ligands [20]. Upon B7 ligation, CTLA-4 mediates down-modulation of T-cell responses through different mechanisms including induction of IL-10 and TGF-β1 production [21]. Although use of antibodies and CTLA-4-Ig to block co-stimulation through CD28 have been widely explored [22–24], it has been most successful in the treatment of cancer [25] and in enhancing graft survival [26]. In contrast, treatment with anti-CTLA-4 has been found to act as an antagonist and exacerbate responses against self-antigens in several autoimmune disease models [27–29]. It has been suggested that agonistic signals are delivered by anti-CTLA-4 antibodies only during antigen presentation by antigen presenting cells resulting in active down modulation of antigen specific T-cell responses [30]. Similarly, anti-CTLA-4 ScFv expressed on the surface of pancreatic β-cells was also able to inhibit β-cell specific autoimmune T-cells in a transgenic mouse model [31], suggesting that CTLA-4 engagement needs to occur simultaneously during TCR interaction with MHC bound antigen for agonistic signaling to occur.

To overcome these limitations of using anti-CTLA-4 to suppress autoimmune diseases, we developed a bi-specific antibody (BsAb) approach and demonstrated that effective antigen (Ag)/target specific T cell tolerance can be induced by enhancing the strength of CTLA-4 engagement and signaling during antigen recognition and/or presentation in the target tissue [32–37]. Earlier, we used a BsAb consisting of a functionally inert anti-TSHR antibody coupled to an agonistic anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Upon inoculation of this BsAb into mice suffering from experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT), the BsAb localized to the thyroid through the anti-TSHR arm and down modulated infiltrating T cell response through the anti-CTLA-4 arm [34], leading to the suppression of EAT. Similarly, we have induced tolerance against alloantigen specific responses [35]. These studies showed that CTLA-4 ligation on activated T cells by the anti-CTLA-4 arm of the BsAb not only actively down-modulated effector T cell function but also converted a proportion of them into antigen/target specific Tregs [33]. To demonstrate the broader applicability of this approach, in subsequent studies, we used thyroglobulin-pulsed or β-cell specific antigenic peptides pulsed DCs coated with anti-CD11C and anti-CTLA-4 BsAb to down modulate antigen specific immune response and suppress EAT in CBA mice [33] and T1D in NOD mice respectively [32].

To develop a more direct and targeted approach for delaying the onset of T1D in NOD mice, it was essential to localize this agonistic anti-CTLA-4 antibody to β-cells in vivo. GLUT2, a transmembrane carrier protein that is involved in passive glucose transport, is predominantly, expressed on the surface of β-cells [38] and is not a target of the autoimmune attack in T1D. Additionally, since the inner and outer glucose-binding sites of GLUT2 are localized in transmembrane segments 9, 10, 11, we reasoned that antibodies binding to the extracellular domain are unlikely to affect its glucose transport function [39] and thus will be functionally inert and suitable for preparing a β-cell targeting BsAb. Therefore, we selected GLUT2, as a potential anchor for BsAb on β-cells. We generated a functionally inert anti-GLUT2 mAb and chemically cross-linked it with the agonistic anti-CTLA-4 mAb to prepare the T-BsAb. In addition, a control bispecific antibody (C-BsAb) was prepared by cross-linking a non-specific mAb to anti-CTLA-4 Ab. The T-BsAb was able to bind to CTLA-4 on T cell surface, and the pancreatic β-cell surface both in vitro and in vivo, and could be safely administered into NOD mice. Treatment of NOD mice at different ages with the T-BsAb protected them from developing hyperglycemia likely by increasing the number of Tregs with concomitant suppression of T cell responses against β cell antigens.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. GLUT2 cDNA cloning

The cDNA corresponding to the ectodomain of GLUT2 (Ecto-GLUT2, ~66 aa) was PCR amplified using primers GCGCCATATGAATGCACCTCAAGAGGTAATAATA and GCGCGGATCCTTAAGACCAGAGCATAGTGACTATGTG. The construct was cloned into an E. coli expression vector (pET15b) in frame with the N-terminal 6 X His tag coding sequence. Recombinant His-tagged Ecto-GLUT2 was expressed in E. coli BL21-DE3 cells. Cell lysate was allowed to bind Ni-NTA agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (with 500 mM NaCl) sodium phosphate buffer with 25–50 mM Imidazole and finally eluted using 250 mM Imidazole.

The full-length GLUT2 (Fl-GLUT2) cDNA (~1.5 kb) was PCR amplified using primers GCGCGGATCCATCAGAAGACAAGATCACCGG and GCGCGAATTCTCACACACTCTCTG-AAGACGC and cloned into a mammalian expression vector (pCDNA3.1-HisB) in frame with the coding sequence for an N-terminal 6 x His tag. HEK 293 cells were transfected with this plasmid and G418 resistant stable clones were selected. After lysis and separation of cytosolic fraction, cell membrane fraction was solubilized in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (with 500 mM NaCl) containing 2% Tween 20. Solubilized recombinant protein was purified by passing the supernatant over Ni-NTA agarose column and the bound protein was eluted using sodium phosphate elution buffer containing 250 mM Imidazole and 2% Tween 20.

2.2. Reverse Phase HPLC

Recombinant Ecto-GLUT2 eluted from Ni-NTA agarose was further purified by a gradient RP-HPLC (Hewlett Packard 1100; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a Phenomenex Kinetex column (C18, 4.6 mm ID x 250 mm L, 5 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size) using a binary solvent system consisting of solvent A=0.1% TFA (v/v) in water and solvent B: 0.1% TFA (v/v) in acetonitrile at flow rate of 1 mL/min. Protein fraction was detected by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF).

2.3. Mice

Wild-type Balb/c and NOD/LtJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Breeding colonies of these mice were also established and maintained in a pathogen-free facility of the biological resources laboratory (BRL) of the University of Illinois at Chicago (Chicago, IL). CB-17 SCID mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY). Glucose levels in the tail vein blood samples of mice were monitored with the ACCU-CHEK blood glucose test strips with a blood glucose meter. The animal studies were approved by the animal care and use committee of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

2.4. Treatment of mice

For the generation of anti-GLUT2 mAbs, 6 week old female Balb/c mice were immunized with 50 μg of Ecto-GLUT2 repeatedly until serum Ab levels showed GLUT2 specific IgG response at a dilution of 1:90,000. Mice were then boosted with a final immunization, sacrificed and their splenocytes used for the preparation of hybridomas.

To determine in vivo tissue binding of antibodies, CB-17 SCID mice were injected i.v with 100 μg of BsAbs via tail vein and euthanized after 3 hours. Mouse pancreata were sectioned and stained to detect T-BsAb binding.

Female 8 and 10 week old NOD mice were injected i.v. via tail vein with 100 μg of T-BsAb or C-BsAb or left untreated (10 mice/treatment group) at 2-week intervals and examined for blood glucose levels every week up to twenty three weeks of age. At twenty five weeks, mice were sacrificed to determine ex vivo antigen specific T cell response. Pancreata were subjected to histopathological examination.

2.5. ELISA

For determination of anti-Glut2 antibodies in the sera of immunized mice, Nunc Polysorp plates were coated with 25 μg/well of purified recombinant Ecto-GLUT2, After blocking and washing, different dilutions of mouse sera, hybridoma supernatants or purified IgG were added and incubated for 2 h. Antibody binding was detected using a horse radish peroxidase (HRP) labelled anti-mouse IgG (Promega, Madison, WI) followed by addition of the TMB substrate. Optical density was determined using a BioRad iMark Microplate Reader. Secreted insulin and insulin content was assayed using the Ultra-Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem Inc. Downers Grove, IL, USA) following manufacturer’s protocol. IFN-γ and IL-10 levels in co-culture supernatants were determined by Mouse Th1/Th2 ELISA Ready-SET-Go ELISA kit (ebioscience) following manufacturer’s protocol.

2.6. Western Blot

Ecto-GLUT2 and FL-GLUT2 were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and probed with commercial polyclonal anti-GLUT2 (rabbit IgG) antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by the addition of secondary anti-rabbit IgG HRP (Promega, Madison, WI). In other cases, membranes were probed with hybridoma supernatants or purified IgGs, followed by the addition of secondary anti-mouse IgG HRP (Promega, Madison, WI). Blots were developed with ECL-Plus Western Blot detection System (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.7. Cell lines, mAbs and BsAbs

Hamster anti-mouse CTLA-4 hybridoma (UCI0-4-F-I0-11) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in complete RPMI 1640 medium with 10% Fetalclone (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and the Abs were purified using Protein A-agarose affinity columns (SantaCruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Anti–CTLA-4–anti-GLUT2 BsAb (T-BsAb) was prepared using Pierce Protein-Protein Cross-linking Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Briefly, the anti-CTLA-4 mAb was allowed to react to 5-fold molar excess of the hetero-bi-functional cross linker sulpho-Succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC). In parallel, the anti GLUT2 mAb (or a non-specific mAb to prepare the C-BsAb) was reduced with 2-Mercaptoethylamine-HCl. Finally the two modified antibodies were mixed with each other to facilitate cross linking. Binding efficiency of BsAbs to GLUT2 and CTLA-4 was tested by FACS using mouse insulinoma cell lines Min 6 and β-TC-6, and NOD splenocytes respectively.

2.8. Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion Assay

Insulin secretion by Min 6 cells was evaluated in a glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) test. Briefly, cells were washed and incubated at 37 °C in Krebs-Ringer buffer containing 2.8 (basal) or 16.7 (stimulated) mmol/liter glucose for 1 hr each. Insulin was extracted from the islets by treating overnight with 0.18 mol/liter of HCl in 70% ethanol and the insulin content was determined by ELISA.

2.9. In vitro T cell assays

Splenic APCs (5 × 104 cells/well) were cultured in 96-well round-bottom plates in triplicate along with CFSE-labeled or unlabeled purified CD4+ T cells (1 × 105/well) from hyperglycemic NOD mice in the presence or absence of β-cell specific antigens. Some of these co-cultures were supplemented with T-BsAb at 20 μg/ml (hi), and 10 μg/ml (lo); or with C-BsAb at 20 μg/ml. After 5 days of culture, CFSE-labeled cells were examined for CFSE dilution and Foxp3 induction by FACS.

2.10. FACS analysis

Total splenocytes and Min-6 cells were washed (with PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA) and incubated with fluorochrome labeled anti CD4-efluor 450, anti-CTLA-4 PE (ebioscience, San Diego, CA); fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated with unlabelled guinea pig-derived anti-insulin antibody (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA), purified anti-GLUT2 (H5, E7 and D2 mAbs), anti-CTLA-4 mAbs and BsAbs in different combinations on ice for 30 min. Some samples were further washed and probed with fluorochrome labeled anti-guinea pig IgG-TRITC (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA), anti-mouse IgG-FITC or anti-Hamster. FITC-IgG (ebioscience, San Diego, CA) stained cells were washed three times and analyzed by Cyan flow cytometer (Beckman/Coulter). For analysis of intracellular Foxp3, cells were fixed/permeabilized and incubated with anti-Foxp3-APC antibodies.

2.11. Immunofluorescence and H&E staining

Pancreatic, liver and kidney tissues were sectioned and the fixed tissue sections were pre-treated and incubated with primary anti-GLUT2 mAbs, anti-insulin antibody. Slides were washed and incubated with fluorochrome labelled secondary anti-mouse, anti-guinea pig or anti-goat Abs respectively. Sections were co-stained with DAPI. Stained sections were visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. Some sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin to determine lymphocytic infiltration. Islets were scored for insulitis in a range between 0–4 where 0 corresponded to no infiltration and 4 corresponded to >50% infiltration.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Mean, standard deviation, and statistical significance for all in vitro and ex vivo analyses were calculated using the MS-Excel application software. Statistical significance of treatment was determined by comparing T-BsAb treated groups with the control group using log rank test, while the statistical significance of suppression of insulitis was determined using Fisher’s exact test as done before [32]. Statistical significance for the comparing disease incidence was determined by Chi-square test using the online chi-square calculator from quantpsy.org [40].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Production of recombinant GLUT2

To be able to effectively coat islet β-cells with anti-CTLA-4 antibody, an antibody that could recognize the ectodomain of GLUT2 on the β-cell surface without affecting its glucose transporter function was needed. Since commercially available and previously reported anti-GLUT2 antibodies were not suitable for our study, we generated anti-GLUT2 mAbs with above described characteristics. To ensure display of native epitopes and retention of native conformation, we produced both Ecto- and FL-GLUT2 recombinant proteins. Recombinant Ecto-GLUT2 (predicted ~10 kD) was expressed in E. coli BL21-DE3 cells and purified by Ni++ affinity chromatography and the purity of the protein was confirmed by staining with Coomassie blue (Fig 1A, upper left panel) and western blot using a commercial anti-GLUT2 antibody (Fig 1A, upper right panel). Likewise, recombinant FL-GLUT2 (major band approximately ~ 53–61 kD) was expressed in stably transfected HEK-293 cells, purified on a Ni-NTA agarose column (Fig. 1A, lower left panel) and confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 1A, lower right panel). FL-GLUT2 was partially pure and was used only for initial screening of anti-GLUT2 mAbs to identify antibodies capable of recognizing native GLUT2.

Figure 1. Expression and purification of recombinant GLUT2.

A) Upper panel: Recombinant GLUT2 ectodomain (Ecto-GLUT2; position on gel shown by black triangle) was produced in E. coli, purified using Ni++ affinity chromatography and resolved on SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining (left) and western blot (right). Lower panel: Recombinant full length GLUT2 (FL-GLUT2) was produced in HEK-293 cells, solubilized by re-suspending membrane fraction in 2% tween-20, purified using Ni++ affinity chromatography (left; position on gel shown by white triangle) and resolved on SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining (left) and western blot (right). FT-flow through; W-wash; E-elution. B) Ecto-GLUT2 bulk purified by Ni-NTA agarose (left) was further purified by Reverse Phase HPLC (right) to >95% purity. Dilutions of BSA standard and Ecto-GLUT2 were loaded for comparison of protein quantities (M- protein marker).

For mouse immunization, Ecto-GLUT2 was expressed in large scale and purified (>95% purity) from E. coli lysate sequentially; first by using a Ni-NTA agarose column (Fig. 1B, left) followed by reverse phase HPLC (Fig. 1B, right). Purified Ecto-GLUT2 was subsequently dialyzed and concentrated. The identity of the protein was confirmed by Mass Spectrometry.

3.2. Generation and characterization of anti-GLUT2 mAbs

When GLUT2 immunized mice showed high titers of antibodies (i.e. 1:90,000) to Ecto-GLUT2, they were re-boosted with Ecto-GLUT2 and euthanized after 4 days. Splenocytes from immunized mice were used to prepare hybridomas and culture supernatants were tested for anti-GLUT2 antibodies by ELISA against Ecto-GLUT2. Hybridomas producing anti-GLUT2 antibodies were cloned and further screened by western blot against FL-GLUT2. Three clones, viz. H5, E7 and D2 that were highly specific for Ecto-GLUT2 and FL-GLUT2 by western blot were selected (Fig 2A). Supernatants containing these three Abs were tested for their ability to recognize native GLUT2 expressed on the surface of Min6 mouse insulinoma cells by FACS using a secondary anti-mouse Ab. GLUT2 non-binding 3B11 hybridoma supernatant was used as a negative control. (Fig. 2B). These results clearly showed that supernatants from hybridomas H5, E7 and D2 can bind to Min6 cell surface.

Figure 2. Characterization of anti-Glut2 mAbs.

A) Supernatants from hybridomas D2, E7 and H5, which contained anti-Ecto-GLUT2 antibodies were used to probe for their ability to bind Ecto-GLUT2 and FL-GLUT2 in lysates from recombinant E. coli and HEK/293 cells respectively. Antibodies H5, E7 and D2 which recognized both recombinant Ecto-GLUT2 and FL-GLUT2 (positions shown by white and black triangles respectively) were selected for further characterization (E-ectodomain; FL-full length). B) Anti-GLUT2 monoclonal antibodies recognize native GLUT2 expressed on Min-6 cells as revealed by Flow cytometry. 3B11 served as a non-specific control antibody. C) Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion in β-TC-6 cell line treated with 50 μg/ml anti-Glut2 mAbs (D2, E7 and H5) show no defect in insulin secretion. D) Anti-GLUT2 mAb H5 binds to islet cells as shown by immunofluorescence using pancreatic tissue sections. Slides were co-stained with an anti-insulin antibody.

To test if mAb binding interfered with GLUT2 function, β-TC-6 mouse insulinoma cells were seeded into 96 well plates and incubated overnight with media alone (control) or media supplemented with one of the 3 purified mAbs (i.e. D2, E7 and H5). Insulin secretion was induced using Krebs 16.7 mM glucose solution for 1 h and was quantified by ELISA. Similar insulin secretion in the control and anti-GLUT2 Ab treated cells indicated that none of the mAbs affected insulin secretion and therefore, GLUT2 function was likely not perturbed by the mAb binding (Fig. 2C).

Anti-GLUT2 mAb H5 showed the strongest binding to ecto-GLUT2 with least background on western blot (Fig 2A) and was thus selected for subsequent experiments. First, it was tested for its capacity to bind to mouse pancreatic islets (Fig 2D). Anti-insulin staining of fixed section of mouse pancreatic tissue showed co-localization of anti-GLUT2 mAb H5 and anti-insulin antibodies on pancreatic islets. These results clearly indicated that we had successfully generated a functionally inert anti-GLUT2 mAb that was capable of binding to GLUT2 on pancreatic β-cells.

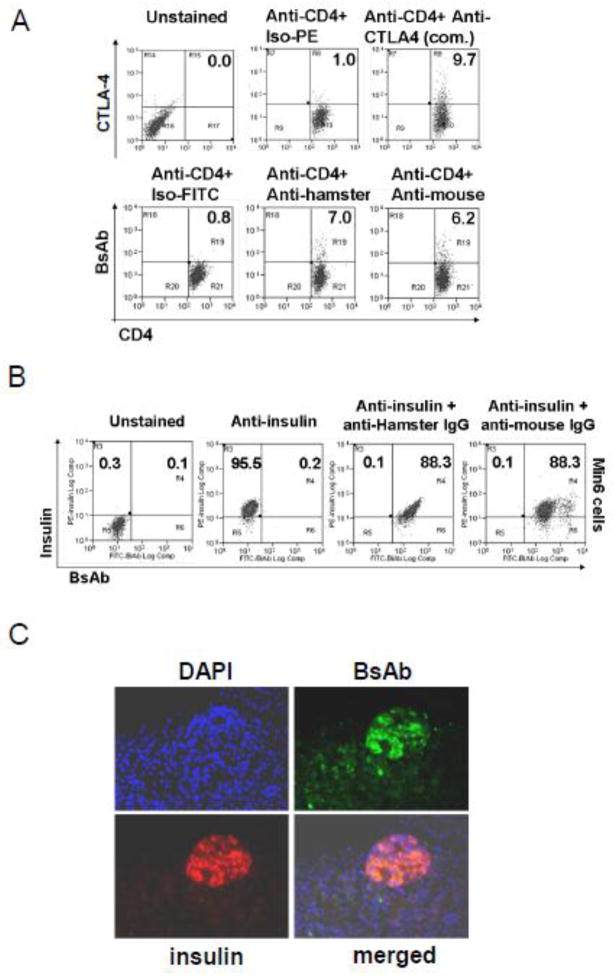

3.3. Construction and characterization of anti-GLUT2-anti-CTLA-4 BsAb

Purified anti-GLUT2 (H5) or a non-specific mouse Ig (hybridoma 3B11) and anti-CTLA-4 IgGs were chemically coupled to generate the test BsAb (T-BsAb and a control BsAb (C-BsAb) respectively. To determine if the T-BsAb was capable of binding CD4+ T-cells, T-BsAb was used to stain mouse splenocytes (Fig 3A). For determining GLUT2 binding by T-BsAb, mouse-GLUT2-expressing Min6 insulinoma-cells were fixed, incubated with T-BsAb, and probed with an anti-mouse or an anti-hamster secondary Ab (Fig 3B). Splenocytes and Min6 cells were co-stained with anti-CD4 and anti-insulin Abs respectively. As expected, irrespective of the 2nd antibody used for the detection of T-BsAb binding, 6.2 to 7% of the CD4+ T cells were double positive for CD4 and CTLA-4 expression (Fig. 3A-lower panel) which was comparable to that detected using a commercial anti-CTLA-4 Ab (Fig. 3A-upper right panel). Similarly, irrespective of the 2nd antibody used, nearly 90% of the Min6 cells were double positive for intra-cellular insulin and cell surface GLUT2 expression (Fig. 3B). These results showed that the T-BsAb could bind well to native CTLA-4 expressed on T cells and GLUT2 expressed on insulinoma cells.

Figure 3. Expression Characterization of anti-CTLA-4/anti-GLUT2 BsAb.

A) T-BsAb can recognize CTLA-4 on CD4+ T-cells. Splenocytes were incubated with T-BsAb and the antibody binding was detected using FITC-conjugated secondary anti-hamster or anti-mouse Abs. Commercial fluorescence-conjugated anti-CD4 and anti-CTLA-4 (upper right panel) were used for co-staining. B) T-BsAb retains its capacity to bind to GLUT2 on Min6 cells. Min 6 cells were incubated with T-BsAb and anti-insulin antibodies and antibody binding was detected using either FITC-conjugated secondary anti-hamster or anti-mouse Abs (for BsAb) and TRITC-conjugated secondary anti-guineas pig antibody (for anti-insulin IgG). C) T-BsAb can bind to GLUT-2 on pancreatic β cells in vivo. CB.17-SCID mice were injected with T-BsAb and pancreatic tissue isolated. Fixed pancreatic tissue sections were incubated with anti-insulin (TRITC) and anti-hamster-IgG-FITC.

To determine if the T-BsAb can bind to β-cells in vivo, we used CB17-SCID mice, which are devoid of endogenous immunoglobulins and thus cannot interfere with the secondary IgG binding to T-BsAb in subsequent immunohistochemical staining. We injected 100 μg purified T-BsAb i.v. into CB17-SCID mice and harvested the pancreas after 3 hours. Direct IF staining of pancreatic tissue sections using an anti-hamster secondary Ab showed that the T-BsAb (shown in green) could bind to the GLUT2-expressing and insulin-containing (shown in red) pancreatic islet cells in vivo (merged image) (Fig 3C). Corresponding staining of kidney tissue sections did not show any T-BsAb binding (Supplementary figure 1).

3.4. Evaluating the safety of BsAb treatment

To ensure that T-BsAb can be used safely we treated 6 week old NOD mice 3 times with 100 ug of BsAb at 2-week intervals and compared with untreated controls. At the end of the treatment period both groups of mice remained normoglycemic (data not shown) and indicated that the T-BsAb treatment did not adversely affect GLUT2 function in vivo. Additionally, we measured the serum levels of Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) to detect damage to hepatocytes and ii) Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) test to detect changes in renal function and found no significant changes in their values relative to control mice (Fig 4A). Moreover, histopathological examination of the liver and kidney tissues from BsAb treated and control mice failed to reveal any damage to the tissues (Fig. 4B) as a consequence of BsAb treatment.

Figure 4. Lack of undesirable side effects of BsAb.

A) NOD mice were either left untreated or treated with T-BsAb bi-weekly. Sera from treated mice were analyzed for evidence of perturbation of liver or kidney function by ALT and BUN tests respectively. B) Histology of liver and kidney tissues as revealed by H&E staining showed no apparent difference between untreated and T-BsAb treated mice. C) GSIS on mouse β-TC-6 cells (left) or isolated mouse islets (right) either in the presence of 50μg/ml of T-BsAb or the C-BsAb show no defect in insulin secretion in response to glucose stimulation.

To extend our observation of functional neutrality of anti-GLUT2, we isolated pancreatic islet cells and seeded them into 96-well plates. We treated β-TC-6 cells (Fig 4C left panel) and isolated islets (Fig 4C right panel) with different doses of the T-BsAb or the C- BsAb for 24–48 hrs. We found no difference in Glucose Stimulated Insulin secretion (GSIS) between untreated, C-BsAb and T-BsAb treated cultures (Fig 4C). From these results, we concluded that T-BsAb treatment did not cause apparent perturbation in islet, liver or kidney function and was thus safe to use in therapeutic studies.

3.5. Determination of efficacy of BsAb treatment

Almost 80% of the female Non-obese diabetic (NOD mice) develop spontaneous diabetes by 12–28 weeks of age. To test if BsAb treatment could prevent the onset of diabetes, we treated 8 and 10 week old pre-diabetic NOD mice, bi-weekly, with T-BsAb or C-BsAb at 100μg per dose and monitored blood glucose every week. Initiation of T-BsAb treatment starting at either 8 or 10 weeks of age caused a significant delay (p=0.015 and p=0.047 v/s untreated group for treatment initiated at 8 weeks and 10 weeks respectively; log-rank test) in the onset of diabetes (Fig 5A and B). In contrast, treatment with C-BsAb showed only marginal effect (p=0.21 and p=0.296 v/s untreated group for treatment initiated at 8 and 10 weeks respectively; not significant by log-rank test). Disease incidence was also significantly lower in T-BsAb treated mice relative to untreated controls (p=0.01 and p=0.02 v/s untreated group for treatment initiated at 8 weeks and 10 weeks respectively; chi-square test). In contrast, treatment with the C-BsAb did not significantly reduce the incidence of the disease (p=0.21 and 0.33 v/s untreated group for treatment initiated at 8 and 10 weeks respectively; not significant by chi-square test), For example, in mice in which the treatment was initiated at 8-weeks of age, 9/10, 6/9 and 3/9 mice in the untreated, C-BsAb (p=0.21 v/s untreated) and T-BsAb (p=0.01 v/s untreated) group were hyperglycemic by 23 weeks of age (Fig. 5B). These results showed that treatment with T-BsAb, unlike mice treated with C-BsAb, can cause a significant delay in the onset of diabetes relative to untreated NOD mice. We also assessed the extent of lymphocytic infiltration of the pancreatic islets in the treated mice. H&E staining of pancreatic tissue sections from the 10-week treatment group of mice selected at random revealed extensive lymphocytic infiltration (insulitis) of pancreatic tissue in untreated mice, and a slightly lesser extent in C-BsAb treated mice (p=0.24 by Fisher’s exact test; not significant), while it was significantly lower (p=0.04 by Fisher’s exact text) in the T-BsAb group than the untreated group (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Therapeutic Efficacy of BsAb in NOD mice.

A and B show percentages of NOD mice that remained normoglycemic up to 23 weeks of age upon initiation of treatment beginning at the age of 8 weeks (N=10 for untreated group; N=9 for C-BsAb and T-BsAb groups) or 10 weeks (N=10 for all groups) respectively. Statistical significance was determined by comparing T-BsAb group with control group using log rank test C) (Upper panel) Representative picture of H&E stained sections showing scheme of insulitis score. (Lower panel) Bar diagrams show insulitis of islets (percentage) in T-BsAb treated group relative to either the C-BsAb treated or untreated controls. Statistical significance was determined using Fisher’s exact test.

3.6. Effects of T-BsAb on Tregs and cytokines

Our earlier studies in several experimental models [32–35] have shown that BsAb mediated engagement of CTLA4 could increase Treg numbers both in vivo and ex vivo. To see if the T-BsAb treatment could increase Tregs and immunomodulatory cytokines, and suppress Teff responses, we isolated splenic CD4+ T-cells from hyperglycemic NOD mice, labeled them with CFSE and co-cultured them with splenic APCs in the presence of immunodominant β-cell Ag peptides and total pancreatic cells. These cultures were left untreated or treated with different concentrations of T-BsAb or C-BsAb. After 96-hours of co-culture, we noticed an increase in the frequency of Tregs in the T-BsAb treated cultures (9.1±1.0%; p<0.01 v/s control with no BsAb at 5.8±0.9%) relative to the C-BsAb treated cultures (7.2±0.9%%; not significant v/s control with no BsAb at 5.8±0.9%) (Fig 6A, upper panel). Furthermore, when we gated on CD4+Foxp3− cells in the co-culture, we noted suppression of CD4+Foxp3− T-cell proliferation in the presence of T-BsAb (6.6±0.5%; p<0.01 v/s control with no BsAb at 10.4±1.2%) but not C-BsAb (9.5±1.9%%; not significant v/s control with no BsAb 10.4±1.2%) (Fig 6A, Lower panel). We also determined the level of IFN-γ and IL-10 from the supernatants of similar co-cultures by ELISA. Relative to controls (no BsAb or C-BsAb), T-BsAb reduced the levels of IFN-γ and increased the levels of IL-10 in these co-cultures as expected (Fig 6B). However we could not detect any variation in the percentage of IL-17 producing T-cells in these co-cultures (data not shown). These results indicated that treatment with T-BsAb increased the number of Tregs, which most likely contributed to the observed suppression in T cell response.

Figure 6. Immunomodulation upon treatment with T-BsAb.

A) CD4+ T-cells were isolated from spleens of NOD mice, labeled with CFSE and incubated with splenic APCs, immunodominant β-cell Ag peptides and total pancreatic cells in the presence or absence of C-BsAb or T-BsAbs. Foxp3 Tregs are increased in cultures supplemented with T-BsAbs (upper panel). CD4+Foxp3− T-cells were gated for measuring the extent of CFSE dilution which shows reduced proliferation in the presence of T-BsAbs. (lower panel). B) Supernatants from co-cultures were analyzed for the presence of IFN-γ and IL-10 by ELISA. Data are representative of two independent experiments with cells pooled from 3–5 mice (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01).

4. DISCUSSION

Several studies have targeted CTLA-4 to treat different experimental autoimmune diseases [26, 30, 33, 35, 41]. However, anti-CTLA-4 has been shown to induce antagonistic effects leading to enhanced autoimmunity [27–29]. As a result, it is believed that only cell-surface bound anti-CTLA-4 is capable of delivering agonistic signals through CTLA-4, and that to only during active antigen presentation [30, 31]. Because of these potential limitations, we developed a novel BsAb that allows for preferential engagement of CTLA-4 on pancreatic islet infiltrating subset of T cells as a targeted therapy for T1D. In order to produce our BsAb, first we generated a functionally neutral mAb against GLUT2 that was able to bind to GLUT2 on β-cell surface without affecting its morphology, viability, ability to secrete insulin in response to glucose stimulation. We chemically coupled one of these antibodies to an agonistic anti-CTLA-4 mAb to create the T-BsAb that recognized both CTLA-4 on T cells and native GLUT2 expressed on mouse insulinoma as well as pancreatic β cells. Moreover, the T-BsAb could co-localize with insulin producing β cells in the pancreatic islets in vivo without exhibiting any off target effects on liver or kidney, tissues in which GLUT2 is also expressed. Furthermore, T-BsAb binding to GLUT2 expressed either on insulinoma cells or isolated islets affected the ability of these cells to secrete insulin in response to glucose stimulation. Most importantly, the T-BsAb treatment could significantly delay the onset of hyperglycemia in NOD mice.

Although it did not reach a level of significance, we noted some protective effect of the C-BsAb, which was not unanticipated. This marginal protective effect of C-BsAb could be due to a broader and non-targeted immunosuppressive effect of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, which may also be the case for T-BsAb mediated therapy. Additionally, some of the T-BsAb or C-BsAb may have diffused into the lymphoid organs after treatment where it could bind to CTLA-4 expressed on other activated T-cells. However, even if T-BsAb could bind to non-β cell specific activated T cells with up-regulated CTLA-4 expression, such a binding would, in most instances, occur in the absence of TCR engagement and thus would neither inhibit the function of those T cells nor convert them into Tregs. Additionally, since CTLA-4 is either not expressed or expressed at a very low level on resting T cells, one would expect no to minimal BsAb binding to most of those T cells in the animal. It is likely that most of the activated β cell specific T cells in NOD mice with T1D reside in the pancreatic microenvironment where T-BsAb was localized. Thus, we believe that broader immunosuppression is not a major concern with anchored anti-CTLA-4 based therapy. Similar approaches, in which β-cell specific expression of CTLA-4-agonist led to inactivation of diabetogenic T-cells and protection of these transgenic NOD mice from developing T1D have been successfully used by another group [31].

Pancreatic β-cells are not known to express MHC-II [42]. Thus we do not believe that T-BsAb bound β-cells act simultaneously as APCs for CD4+ Teffectors. One possibility is that pancreas-resident APCs engage CD4+ Tffectors through autoantigen specific TCRs while β-cells-bound T-BsAb deliver the CTLA-4 signal in trans as has been suggested by an earlier study in which a CTLA4 agonist was specifically expressed on beta cells [31]. Because of this co-localization of β cell specific T cells and the T-BsAb, it is likely that the T-BsAb primarily down modulated infiltrating T cells and converted a proportion of them into Tregs and suppressed diabetes.

Evidence suggests that loss of immune regulation by Tregs controls the progression of diabetes [43]. and earlier we have shown that restoration of Treg numbers by BsAb treatment can suppress autoimmune T-cell functions via increased production of TGF-β and IL-10 [32, 34, 35]. Interestingly, in the presence of T-BsAb, we found suppressed T cell proliferation, decreased IFN-γ production and increased IL-10 production ex vivo in response to β cell antigens. The mechanism by which CTLA-4 engagement induces Foxp3+ Tregs is not yet known. Foxp3+ adaptive Tregs (iTregs) are generated in the periphery through the TCR-based activation of Foxp3− T-cells in the presence of the cytokine TGF-β [44, 45]. Interestingly, it has been shown that TGF-β mediated induction of adaptive Tregs requires CTLA-4 [46]. Thus, while islet-resident APCs themselves may be secreting TGF-β during TCR-engagement of autoimmune T-cells, co-ligation of CTLA-4 by β-cells through T-BsAb in-trans may enhance this process leading to efficient conversion of iTregs. In contrast, other groups have proposed the involvement of a T-cell-intrinsic mechanism of generating adaptive Tregs through CTLA-4 ligation, since treating T cells with an agonistic anti-CTLA-4 antibody resulted in Treg induction in vitro [47]. Further investigation is required to elucidate the precise mechanism by which CTLA-4 engagement facilitates Treg induction.

In conclusion, the targeted engagement of CTLA-4 by an agonistic antibody may lead to the development of tolerance against β-cell antigens and thus prevent destruction of β cells and development of diabetes in NOD mice. Hence our BsAb approach can become the solution to the problem of current experimental therapies that broadly suppress immune response, and lack target tissue or autoantigen specificity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We produced inert anti-GLUT2 mAbs that bound pancreatic β-cells in vitro.

We constructed a BsAb by chemically coupling an anti-CTLA-4 and an anti-GLUT mAb.

Upon injection into mice, BsAbs could bind to GLUT2 on pancreatic β-cells in vivo.

BsAb treatment did not adversely affect liver kidney or β-cell function.

BsAb treatment significantly delayed the onset of T1D in NOD mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant # 1R41AI085677-01 to Dr. Prabhakar from the National Institutes of Health and by Tolerogenics, a startup biotech company in Illinois.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen Presenting Cells

- BsAb

Bispecific antibody

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen - 4

- GLUT2

Glucose transporter 2

- Treg

regulatory T-cells

- DCs

dendritic cells

- BMDCs

bone marrow derived DCs

- T1D

type-1 diabetes

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- BUN

Blood Urea Nitrogen

- GSIS

Glucose stimulated insulin secretion

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

PB, and BSP designed study, analyzed data and wrote manuscript. PB, JF, CH, AE, AG and HAE conducted experiments. CV and BSP made critical manuscript revisions to provide intellectual content. BSP supervised project and is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS. Type 1 diabetes: new perspectives on disease pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet. 2001;358(9277):221–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd JA, Wicker LS. Genetic protection from the inflammatory disease type 1 diabetes in humans and animal models. Immunity. 2001;15(3):387–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon JW, Jun HS. Cellular and molecular pathogenic mechanisms of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;928:200–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kukreja A, et al. Multiple immuno-regulatory defects in type-1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(1):131–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skarsvik S, et al. Poor in vitro maturation and pro-inflammatory cytokine response of dendritic cells in children at genetic risk of type 1 diabetes. Scand J Immunol. 2004;60 (6):647–52. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluestone JA. Is CTLA-4 a master switch for peripheral T cell tolerance? J Immunol. 1997;158(5):1989–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindley S, et al. Defective suppressor function in CD4(+)CD25(+) T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(1):92–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alard P, et al. Deficiency in NOD antigen-presenting cell function may be responsible for suboptimal CD4+CD25+ T-cell-mediated regulation and type 1 diabetes development in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2006;55(7):2098–105. doi: 10.2337/db05-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araki M, et al. Genetic evidence that the differential expression of the ligand-independent isoform of CTLA-4 is the molecular basis of the Idd5.1 type 1 diabetes region in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2009;183(8):5146–57. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yadav D, et al. Altered availability of PD-1/PD ligands is associated with the failure to control autoimmunity in NOD mice. Cell Immunol. 2009;258(2):161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maini RN, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552–63. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maini R, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354(9194):1932–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva LC, Ortigosa LC, Benard G. Anti-TNF-alpha agents in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: mechanisms of action and pitfalls. Immunotherapy. 2010;2(6):817–33. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatenoud L. CD3-specific antibody-induced active tolerance: from bench to bedside. Nature reviews Immunology. 2003;3(2):123–32. doi: 10.1038/nri1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung DT, et al. Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by expanding myelin antigen-specific Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. International immunology. 2007;19(8):1003–10. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masteller EL, et al. Expansion of functional endogenous antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2005;175(5):3053–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masteller EL, et al. Peptide-MHC class II dimers as therapeutics to modulate antigen-specific T cell responses in autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2003;171(10):5587–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linsley PS, et al. Human B7–1 (CD80) and B7–2 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors. Immunity. 1994;1(9):793–801. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tivol EA, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3(5):541–7. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linsley PS, et al. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174(3):561–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saverino D, et al. Dual effect of CD85/leukocyte Ig-like receptor-1/Ig-like transcript 2 and CD152 (CTLA-4) on cytokine production by antigen-stimulated human T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(1):207–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Londrigan SL, et al. In situ protection against islet allograft rejection by CTLA4Ig transduction. Transplantation. 2010;90(9):951–7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f54728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vergani A, et al. A novel clinically relevant strategy to abrogate autoimmunity and regulate alloimmunity in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(9):2253–64. doi: 10.2337/db09-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2 (2):116–26. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271(5256):1734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenschow DJ, et al. Long-term survival of xenogeneic pancreatic islet grafts induced by CTLA4lg. Science. 1992;257(5071):789–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1323143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrin PJ, et al. CTLA-4 blockade enhances clinical disease and cytokine production during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1996;157(4):1333–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurwitz AA, et al. Specific blockade of CTLA-4/B7 interactions results in exacerbated clinical and histologic disease in an actively-induced model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;73(1–2):57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luhder F, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) regulates the unfolding of autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 1998;187(3):427–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fife BT, et al. Inhibition of T cell activation and autoimmune diabetes using a B cell surface-linked CTLA-4 agonist. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2252–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI27856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shieh SJ, et al. Transgenic expression of single-chain anti-CTLA-4 Fv on beta cells protects nonobese diabetic mice from autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2009;183(4):2277–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karumuthil-Melethil S, et al. Dendritic cell-directed CTLA-4 engagement during pancreatic beta cell antigen presentation delays type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6695–708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li R, et al. Enhanced engagement of CTLA-4 induces antigen-specific CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ and CD4+CD25− TGF-beta 1+ adaptive regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5191–203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasu C, Prabhakar BS, Holterman MJ. Targeted CTLA-4 engagement induces CD4+CD25+CTLA-4high T regulatory cells with target (allo)antigen specificity. J Immunol. 2004;173(4):2866–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasu C, et al. Targeted engagement of CTLA-4 prevents autoimmune thyroiditis. Int Immunol. 2003;15(5):641–54. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez N, et al. Preferential costimulation by CD80 results in IL-10-dependent TGF-beta1(+) -adaptive regulatory T cell generation. J Immunol. 2008;180(10):6566–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao S, et al. Targeted delivery of anti-CTLA-4 antibody downregulates T cell function in vitro and in vivo. Clin Immunol. 2001;101(2):136–45. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorens B, Roduit R. Regulated expression of GLUT2 in diabetes studied in transplanted pancreatic beta cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22(3):684–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0220684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terova G, et al. In vivo regulation of GLUT2 mRNA in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in response to acute and chronic hypoxia. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;152(4):306–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preacher KJ. Calculation for the chi-square test: An interactive calculation tool for chi-square tests of goodness of fit and independence. 2001 [[Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org.]

- 41.Linsley PS, et al. Immunosuppression in vivo by a soluble form of the CTLA-4 T cell activation molecule. Science. 1992;257(5071):792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1496399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McInerney MF, Rath S, Janeway CA., Jr Exclusive expression of MHC class II proteins on CD45+ cells in pancreatic islets of NOD mice. Diabetes. 1991;40(5):648–51. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, et al. Where CD4+CD25+ T reg cells impinge on autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;202(10):1387–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen W, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198(12):1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fantini MC, et al. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25− T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J Immunol. 2004;172(9):5149–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng SG, et al. TGF-beta requires CTLA-4 early after T cell activation to induce FoxP3 and generate adaptive CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176(6):3321–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes MJ, et al. CTLA-4 promotes Foxp3 induction and regulatory T cell accumulation in the intestinal lamina propria. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6(2):324–34. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.