Abstract

Communication between nucleus and cytoplasm extends past molecular exchange and critically includes mechanical wiring. Cytoskeleton and nucleoskeleton are connected via molecular tethers that span the nuclear envelope. SUN-domain proteins spanning the inner nuclear membrane and KASH-peptide bearing proteins residing in the outer nuclear membrane directly bind and constitute the core of the LINC complex. These connections appear critical for a growing number of biological processes and aberrations are implicated in a host of diverse diseases, including muscular dystrophies, cardiomyopathies, and premature aging. We discuss recent developments in this vibrant research area, particularly in context of first structural insights into LINC complexes reported in the past year.

Introduction

The nuclear envelope (NE) is a double-lipid bilayer that separates the nucleus from the cytoplasm. This way, transcription and translation are spatially separated in eukaryotes, enabling sophisticated regulatory mechanisms for gene expression. The NE is an extension of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and consists of an outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and an inner nuclear membrane (INM), evenly separated by the perinuclear space (PNS) of ~50 nm width. ONM and INM are fused at circular openings, occupied by nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). Macromolecular trafficking between the nucleus and the cytoplasm occurs mainly through NPCs [1,2], although recent findings suggest a vesicular transport mechanism across the PNS akin to nuclear egress by herpes viruses may be used for exceptionally large nuclear export cargo [3,4].

Mechanical communication has long been recognized for cells interacting with their surrounding [5]. That the nucleus is also mechanically tethered to its environment has only been uncovered more recently [6]. Since that initial discovery, interest in the subject has grown rapidly. Mechanical coupling of the nucleus to the cytoskeleton can potentially serve many purposes. First, the position of the nucleus within a cell needs to be maintained in many cell types, notably in neurons and muscle cells, suggesting that nuclei require a mechanism to be pulled into their desired place [7]. Second, physical connections across the NE are attractive candidates for mediating mechanotransduction, a very fast signaling mechanism that results in transcription programs triggered by extracellular stimuli [8,9]. Third, these nucleocytoplasmic linkages can also be used to determine the position of specific nuclear structures, like the ends of paired chromosomes during meiosis [10,11]. Underscoring the general importance of the nucleoskeleton and its link to the cytoskeleton, a growing number of diverse genetic disorders, including neurological, muscular, and premature aging have been linked to mutations in its constituents [12–14].

Physical interactions across the nuclear envelope are mediated via LInkers of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes [15,16]. The center of LINC complexes is the interaction of INM-resident SUN (Sad1 and UNC-84) proteins with ONM-resident KASH (Klarsicht, ANC-1 and SYNE/Nesprin-1 and -2 Homology) proteins within the PNS. The SUN-KASH interaction complex has recently been solved by X-ray crystallography, providing a rich basis for detailed studies on LINC function [17].

SUN proteins

SUN proteins are type II membrane proteins conserved across all eukaryotes and typically found in the INM. At the N terminus they contain a variable nucleoplasmic region, followed by a transmembrane helix connecting into a predicted coiled-coil segment localized to the PNS. The most recognizable feature of SUN proteins is a stretch of ~175 amino acids, usually at the very C terminus, termed ‘SUN domain’ based on the homology between Sad1 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe and UN C-84 from Caenorhabditis elegans [18]. With increasing complexity of the organism, the number of SUN proteins also increases. While single cell organisms apparently carry only one SUN domain protein, nematodes and flies contain two genes for SUN proteins, and the mammalian genome encodes at least five distinct members of the SUN protein family, Sun1-5 [16]. The expression of the individual SUN proteins depends on the cell type, suggesting cell type-specific adaption of LINC complexes to meet distinct cellular and physiological requirements. For example, in C. elegans, UNC-84 is expressed in most cells, whereas SUN-1/Matefin expression is restricted to germ cells. Notably, the C. elegans SUN proteins show no overlapping activity, indicating that their respective LINC complexes occupy distinct functions [19]. As in C. elegans, the Drosophila SUN protein Klaroid is present in almost every cell type, whereas SUN4/Spag4 appears to be strictly confined to the male germ line [20,21]. Similarly, the two major mammalian SUN proteins, Sun1 and Sun2, are widely expressed in different cell types [15,22]. In contrast, the three additional genes coding for Sun3, Sun4, and Sun5, respectively, all show a much more restricted, testis-specific expression pattern [23]. In addition to the SUN domains at the C terminus, there are also SUN-like proteins [24,25] with the SUN-like domain in the center of the protein. To what extent SUN- and SUN-like proteins are functionally related is currently a matter of speculation.

One intriguing aspect of SUN proteins is their apparent exclusive localization to the INM. Therefore, a number of studies have focused on understanding the molecular parameters that determine transport to the INM [26,27], as part of an effort to understand INM targeting in general. It appears that multiple factors contribute to targeting and it is not yet clear whether they are universal or whether instead different INM proteins employ distinct mechanisms.

KASH proteins

KASH proteins are so far exclusively found at the ONM and share several common features. They are tail-anchored, single-span transmembrane proteins with a short luminal C terminus. The transmembrane helix together with the 8–30 residues of the luminal tail are well conserved and form the KASH ‘domain’, recognizable by primary sequence analysis (Figure 1) [28]. The most striking feature of the luminal KASH peptide is the terminal ‘PPPX’ motif, where X is always the very terminal residue.

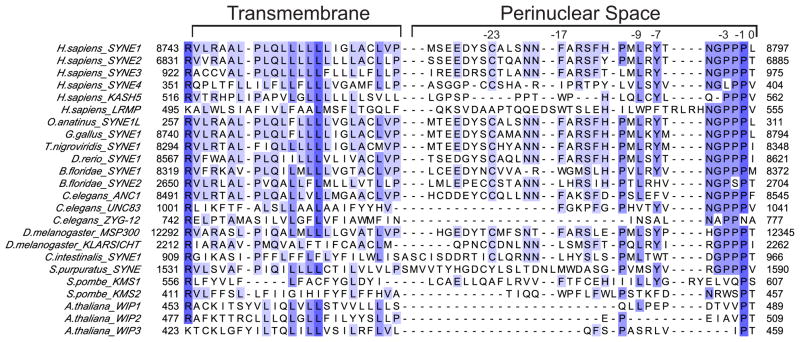

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of KASH peptides from highly diverged eukaryotes, including vertebrates, various metazoans, yeast, and plants. The numbers above the sequence mark residues in human Nesprin2/SYNE2 important for SUN binding according to [17].

Much like SUN proteins, complex organisms tend to have more KASH proteins than simpler ones. To date, we know six KASH proteins in humans, four of which are called Nesprins (for nuclear envelope spectrin repeat). Nesprin 1 and 2 in mammals are exceedingly large, 0.8–1 MDa actin-binding proteins comprising multiple spectrin repeats that serve in nuclear tethering. These proteins generate extensive fibers that emanate deep into the cytoplasm. Nesprin-3, a shorter molecule, binds to plectin, which in turn links to the actin and/or intermediate filaments. Nesprin-4 is restricted to a few cell types and connects to microtubules via the motor protein kinesin. It has recently been shown that C-terminal, KASH-free truncations of Nesprin-4 result in hearing loss [29] KASH5, which binds SUN1, was reported recently to be a germ cell-specific protein involved in meiotic homologue pairing [30]. The ONM-resident, lymphoid-restricted membrane protein (LRMP) is the latest characterized putative KASH proteins [31]. Although its cognate SUN protein is not yet known, LRMP is necessary for pronuclear congression in the fertilized egg. Thus, it fulfills a mechanical task involving the positioning of nuclei and it has the correct topology and KASH peptide sequence, implying that it is another member of the growing KASH family.

SUN-KASH Complex

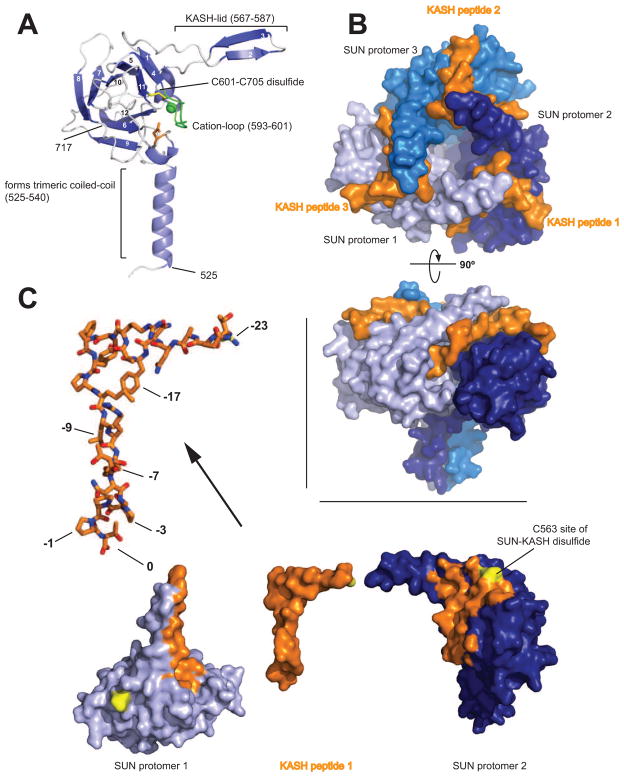

The principal function of the LINC complex is to tether nucleo- and cytoskeleton mechanically, which presumably requires a very strong and stable interaction between SUN and KASH. The crystal structure of the LINC complex published in 2012 illustrates this property quite satisfactorily [17]. The SUN domain itself folds into a beta-sandwich structure, a fairly common fold in eukaryotes. The basic structure is decorated with several SUN-specific features (Figure 2). First, N-terminal to the beta-sandwich, a helical extension forms a triple-stranded coiled coil with adjacent SUN domains, effectively generating a SUN homotrimer. Even though the SUN domains also directly touch neighboring SUN domains, their interactions are too weak to stabilize a trimer without the coiled-coil extension. Second, a ~20 amino-acid extension, the KASH-lid, emanates from the central beta-sandwich and is critical for KASH binding. Third, a conserved ~10 residue loop structure is positioned by a disulfide bond between two highly conserved cysteines. This loop binds a metal ion, and is also involved in KASH binding.

Figure 2.

A) Overview of a human SUN2 protomer isolated from its Nesprin-2 binding partners in the trimeric SUN-KASH complex [17]. The protein is organized around a compact β-sandwich core, decorated with features important for function (labeled). Bound cation depicted as a green sphere. B) View from the ONM facing the bottom of the trimeric SUN2 arrangement (blue colors) with three individual KASH peptides (orange) bound. C) Side view of the SUN2-KASH2 complex. It is easy to recognize how deeply the three KASH peptides are buried in clefts formed between neighboring SUN2 protomers. D) Explosion view of the KASH peptide interacting with neighboring SUN domains in the SUN2 trimer. Areas on the SUN domains in close contact with the KASH peptide are highlighted in orange. Note the L-shaped, extended conformation of the bound KASH peptide. Important residues for SUN interaction are labeled in the zoomed, stick representation of KASH2.

The SUN homotrimer serves as a tailored platform to interact with three KASH peptides (Figure 2B). The peptides are individually bound in three deep grooves, each created by two neighboring SUN protomers. Trimerization of SUN is therefore a prerequisite for KASH binding. The very C terminus of the KASH peptide, amino acid position 0, is buried in a pocket on SUN protomer 1 and the carboxylate makes numerous contacts, explaining the strict conservation of the peptide length (Figure 2C). Adding just one residue abolishes binding [17]. Positions -1 to -3 are typically trans-prolines and are bound in shape-dependent, van-der-Waals manner. After a few more exposed positions, residues -7 to -10 form a short beta-strand that connects the KASH-lid beta-hairpin of protomer 1 with the SUN core domain of protomer 2. Positions -7 and -9 are conserved as large hydrophobic amino acids, and are buried in a cleft between the SUN protomers. Following residue -11 the KASH peptide sharply kinks and lines up on the surface of SUN protomer 2. Except for the buried hydrophobic residue at position -17 conservation is weak in this region, consistent with data indicating that the last 11–14 residues are sufficient for stable SUN2-KASH2 binding [17]. Importantly though, residue -23 encodes a conserved cysteine that crosslinks with the conserved SUN2-cysteine 563, drastically stabilizing the interaction further. In summary, SUN trimerization and the formation of large interfaces between three KASH peptides, each clasped between two neighboring SUN protomers and making many stabilizing interactions, ensure very stable binding. Although the SUN-KASH interaction seen in the crystal structure has no close precedent in other peptide-protein interactions, some beta-sandwich proteins that are distantly related to SUN bind small molecules, often lectins, in a pocket that overlaps the ‘PPPX’ binding site. These F-lectins also contain a metal binding loop, and they also use an intramolecular disulfide bond to stabilize this loop, but they typically do not trimerize. Thus SUN proteins and F-lectins may have evolved from a common ancestor that already had a small molecule binding moiety, which diverged into the different binding interfaces seen in the extant domains.

Conservation of the SUN-KASH interaction

The existing SUN2-KASH1/-2 complex structures suggest that the principal arrangement of three KASH peptides binding a SUN trimer is universally conserved. All SUN domains characterized to date are immediately preceded by predicted coiled-coil segments, suggesting that the characteristic cloverleaf-like, trimeric SUN arrangement is also conserved. In addition, the binding mode whereby two adjacent SUN domains form an elaborate, shared binding site also strongly supports the notion that the general SUN-KASH heterohexameric arrangement is conserved. The KASH peptides in vertebrates are similar enough to expect them all to bind SUN in similar manner. In nematodes, yeast and plants, however, the sequences are quite diverged (Figure 1), and experimental data is therefore needed to make definitive statements about universally conserved, common features.

The coiled-coil segment of SUN proteins

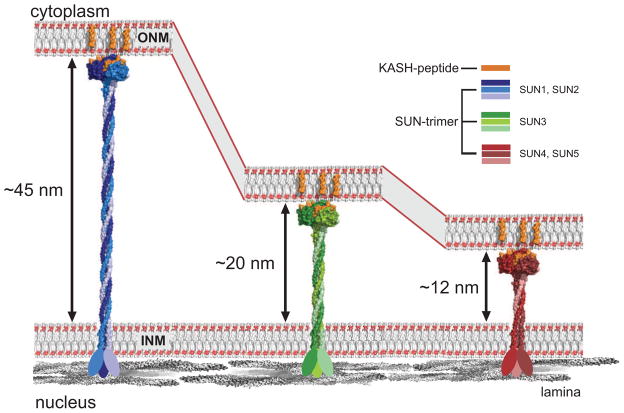

In all SUN proteins the C-terminal SUN domain is preceded by a predicted helical region that spans the remainder of the perinuclear domain. Detailed analyses indicate that these helices can form coiled-coils. As the independently determined apo- and KASH-bound SUN2 structures now show [17,32,33], the region immediately adjacent to the SUN domain forms a non-canonical, right-handed trimeric coiled-coil arrangement with undecan rather than heptad repeat character [34]. Since coiled-coil prediction methods are trained to detect canonical structures, it is plausible that the entire helical domain forms an extended, continuous trimeric coiled-coil. Whether it is right-handed throughout or flips handedness is an open question. The reversal of coiled-coil handedness has been observed previously, and the energetic barrier for the conversion is rather low [35]. The length of the coiled-coil segment can be regarded as a ruler that is either adapted to or determines the width of the PNS. The coiled-coil segments of the ubiquitous SUN1/2 proteins are almost equal in length and would generate an ~45 nm rod (Figure 3). The testis-specific SUN3, SUN4, and SUN5 proteins, however, have shorter predicted coiled-coils. These SUNs are localized in specific NE regions and the shorter intermembrane distance forced by these LINC complexes may have functional importance [23,36].

Figure 3.

Various SUN proteins exhibit predicted perinuclear α-helical coiled-coil domains of various length. If these elements are modeled as trimeric coiled-coils, currently the most likely scenario, spacing between INM and ONM would vary dependent on the employed SUN protein.

Higher-order arrays of LINC complexes

To move the entire nucleus through the cell, LINC complexes must bear substantial mechanical load. Having a connection involving three KASH peptides interacting with a SUN trimer is one way of strengthening the LINC complex. Adding a disulfide bridge covalently linking SUN and KASH is another, but are these interactions sufficient? In fibroblasts, nuclei move away from a wound edge by harnessing the retrograde flow of actin. Here, SUN-KASH bridges in the NE arrange linearly, creating “TAN lines” parallel to the actin fibers to which they are presumably attached [37–39]. It is attractive to think that this 2D arrangement strengthens actin tethering, but this idea awaits experimental verification. In meiotic cells, SUN proteins cluster to bring telomeric chromosome ends together during bouquet formation [11,40–42], again suggesting that higher order LINC clusters are functionally important. Spectrin repeats in Nesprins, as well as additional coiled-coil segments in Nesprin2, are strong candidates for linking individual hetero-hexameric SUN-KASH complexes into larger 2D arrays [17]. The molecular details of such networks and their regulation are exciting topics for future studies.

Regulation of LINC complex formation

So far, LINC complexes are exclusively found in the NE, with SUN proteins crossing the INM and KASH proteins crossing the ONM. SUNs are expected to be inserted cotranslationally into the ER via the Sec61 channel[43], while KASH proteins are tail anchored and might be integrated into the ER via the action of the GET complex [44]. Because both SUNs and KASH proteins are inserted into the ER it is intriguing to consider what prevents premature formation of LINC complexes, and how the cell ensures exclusive formation of SUN-KASH bridges in the PNS. One possibility is that at least one partner is kept in a binding-incompetent state before it reaches its final destination. Perhaps SUN only trimerizes after reaching the INM, and would therefore only gain KASH-binding competence at the target membrane. Another option is that one of the two binding partners is bound to a chaperone before engaging with the proper partner at the NE. The conserved prolines in KASH proteins also invite to speculations about a regulatory role. Maintaining one or more in the cis-conformation (they are all trans in the bound peptide) would be another elegant way of preventing LINC formation at the wrong site.

It is equally important to understand how LINC complexes disassemble and whether they can be remodeled or must be degraded to disassemble? Since the nucleus breaks down during mitosis in multicellular organisms, LINC complexes need to be disassembled at least once each cell cycle. TorsinA, a poorly characterized ER-resident AAA+ ATPase, is an attractive candidate for catalyzing the LINC complex disassembly [45]. Indirect evidence suggests that TorsinA destabilizes selected LINC complexes at the NE, after being recruited to the NE by other proteins.

Conclusions

Recent structural characterization of the core of the LINC complex, the SUN-KASH interaction, has provided researchers interested in mechanotransduction across the NE with a rich platform for analyzing this process in molecular detail. Since LINC-complexes are involved in broadly divergent functions, this will be an exciting field of study for years to come. Given the speed of recent progress, we can expect answers to mechanistic questions (assembly/disassembly/targeting) in the foreseeable future. In addition to uncovering fundame biology, progress in the field will hopefully also lead to therapeutic strategies that for treating the devastating diseases associated with LINC complex malfunctions, and NE diseases in general. An encouraging development in this regard is the recent finding that Sun1 overaccumulates in murine models for Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy and in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome and that reducing Sun1 levels markedly improves these diseases [46].

Highlights.

SUN- and KASH-proteins form mechanical connections across the nuclear envelope.

Crystal structures reveal that these LINC complexes are built from SUN trimers interacting with three KASH peptides.

LINC complexes might define the spacing of inner and outer nuclear membrane

LINC complexes are involved in a growing number of diverse biological functions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to apologize to those colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space limitations. Research in the Schwartz lab was supported by grant R21 NS075883 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and by a grant from the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Brohawn SG, Partridge JR, Whittle JRR, Schwartz TU. The nuclear pore complex has entered the atomic age. Structure. 2009;17:1156–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Görlich D, Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speese SD, Ashley J, Jokhi V, Nunnari J, Barria R, Li Y, Ataman B, Koon A, Chang Y-T, Li Q, et al. Nuclear envelope budding enables large ribonucleoprotein particle export during synaptic Wnt signaling. Cell. 2012;149:832–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose A, Schlieker C. Alternative nuclear transport for cellular protein quality control. Trends Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maniotis AJ, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1997;94:849–854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapley EC, Starr DA. Connecting the nucleus to the cytoskeleton by SUN–KASH bridges across the nuclear envelope. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombardi ML, Lammerding J. Keeping the LINC: the importance of nucleocytoskeletal coupling in intracellular force transmission and cellular function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1729–1734. doi: 10.1042/BST20110686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato A, Isaac B, Phillips CM, Rillo R, Carlton PM, Wynne DJ, Kasad RA, Dernburg AF. Cytoskeletal forces span the nuclear envelope to coordinate meiotic chromosome pairing and synapsis. Cell. 2009;139:907–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chikashige Y, Tsutsumi C, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Meiotic proteins bqt1 and bqt2 tether telomeres to form the bouquet arrangement of chromosomes. Cell. 2006;125:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worman HJ, Bonne G. “Laminopathies”: a wide spectrum of human diseases. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2121–2133. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Méndez-López I, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: impact on human disease. Chromosoma. 2012;121:153–167. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, Rattner JB, Shanahan C, Burke B, Stahl PD, Hodzic D. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starr DA, Fridolfsson HN. Interactions between nuclei and the cytoskeleton are mediated by SUN-KASH nuclear-envelope bridges. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:421–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046. First study to reveal the structural basis of LINC complex formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malone CJ, Fixsen WD, Horvitz HR, Han M. UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development. 1999;126:3171–3181. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridkin A, Mills E, Margalit A, Neufeld E, Lee KK, Feinstein N, Cohen M, Wilson KL, Gruenbaum Y. Matefin, a Caenorhabditis elegans germ line-specific SUN-domain nuclear membrane protein, is essential for early embryonic and germ cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2004;101:6987–6992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307880101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kracklauer MP, Banks SML, Xie X, Wu Y, Fischer JA. Drosophila klaroid encodes a SUN domain protein required for Klarsicht localization to the nuclear envelope and nuclear migration in the eye. Fly (Austin) 2007;1:75–85. doi: 10.4161/fly.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Technau M, Roth S. The Drosophila KASH domain proteins Msp-300 and Klarsicht and the SUN domain protein Klaroid have no essential function during oogenesis. Fly (Austin) 2008;2:82–91. doi: 10.4161/fly.6288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padmakumar VC, Libotte T, Lu W, Zaim H, Abraham S, Noegel AA, Gotzmann J, Foisner R, Karakesisoglou I. The inner nuclear membrane protein Sun1 mediates the anchorage of Nesprin-2 to the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3419–3430. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Göb E, Schmitt J, Benavente R, Alsheimer M. Mammalian sperm head formation involves different polarization of two novel LINC complexes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012072. Interesting paper that explores the roles of testis-specific SUN proteins in spermatogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Field M, Horn D, Alsford S, Koreny L, Rout MP. Telomeres, tethers and trypanosomes. Nucleus. 2012;3:0–8. doi: 10.4161/nucl.22167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada N, Inouye K, Sawai S, Kawata T. SunB, a novel Sad1 and UNC-84 domain-containing protein required for development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Growth Differ. 2010;52:577–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26**.Tapley EC, Ly N, Starr DA. Multiple mechanisms actively target the SUN protein UNC-84 to the inner nuclear membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1739–1752. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0733. Together with [27] these papers are the first to untangle the intricate targeting mechanism of SUN proteins to the INM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Turgay Y, Ungricht R, Rothballer A, Kiss A, Csucs G, Horvath P, Kutay U. A classical NLS and the SUN domain contribute to the targeting of SUN2 to the inner nuclear membrane. EMBO J. 2010;29:2262–2275. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.119. see [26] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starr DA, Han M. Role of ANC-1 in tethering nuclei to the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 2002;298:406–409. doi: 10.1126/science.1075119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Horn HF, Brownstein Z, Lenz DR, Shivatzki S, Dror AA, Dagan-Rosenfeld O, Friedman LM, Roux KJ, Kozlov S, Jeang K-T, et al. The LINC complex is essential for hearing. J Clin Invest. 2013 doi: 10.1172/JCI66911DS1. The KASH protein Nesprin-4 is required for hearing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Morimoto A, Shibuya H, Zhu X, Kim J, Ishiguro K-I, Han M, Watanabe Y. A conserved KASH domain protein associates with telomeres, SUN1, and dynactin during mammalian meiosis. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:165–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201204085. Characterization of KASH5 as a novel germ cell-specific protein critical for meiosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Lindeman RE, Pelegri F. Localized products of futile cycle/lrmp promote centrosome-nucleus attachment in the zebrafish zygote. Curr Biol. 2012;22:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.058. Characterization of Lrmp as a novel KASH protein involved in pronuclear congression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Shi Z, Jiao S, Chen C, Wang H, Liu G, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Greene MI, Zhou Z. Structural insights into SUN-KASH complexes across the nuclear envelope. Cell Research. 2012 doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Z, Du X, Cai Z, Song X, Zhang H, Mizuno T, Suzuki E, Yee MR, Berezov A, Murali R, et al. Structure of Sad1-UNC84 homology (SUN) domain defines features of molecular bridge in nuclear envelope. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5317–5326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruber M, Lupas AN. Historical review: another 50th anniversary--new periodicities in coiled coils. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez BH, Gruber M, Ursinus A, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Lupas AN, Zeth K. A transition from strong right-handed to canonical left-handed supercoiling in a conserved coiled-coil segment of trimeric autotransporter adhesins. J Struct Biol. 2010;170:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kracklauer MP, Link J, Alsheimer M. LINCing the Nuclear Envelope to Gametogenesis. Elsevier Inc; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borrego-Pinto J, Jegou T, Osorio DS, Auradé F, Gorjánácz M, Koch B, Mattaj IW, Gomes ER. Samp1 is a component of TAN lines and is required for nuclear movement. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1099–1105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Luxton GWG, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Vintinner E, Gundersen GG. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 2010;329:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1189072. Suggests that higher-order LINC complexes are functionally involved in nuclear positioning during wound healing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luxton GWG, Gundersen GG. Orientation and function of the nuclear-centrosomal axis during cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penkner AM, Fridkin A, Gloggnitzer J, Baudrimont A, Machacek T, Woglar A, Csaszar E, Pasierbek P, Ammerer G, Gruenbaum Y, et al. Meiotic chromosome homology search involves modifications of the nuclear envelope protein Matefin/SUN-1. Cell. 2009;139:920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding X, Xu R, Yu J, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Han M. SUN1 is required for telomere attachment to nuclear envelope and gametogenesis in mice. Dev Cell. 2007;12:863–872. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitt J, Benavente R, Hodzic D, Höög C, Stewart CL, Alsheimer M. Transmembrane protein Sun2 is involved in tethering mammalian meiotic telomeres to the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2007;104:7426–7431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609198104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rapoport TA. Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature. 2007;450:663–669. doi: 10.1038/nature06384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denic V. A portrait of the GET pathway as a surprisingly complicated young man. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vander Heyden AB, Naismith TV, Snapp EL, Hodzic D, Hanson PI. LULL1 retargets TorsinA to the nuclear envelope revealing an activity that is impaired by the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2661–2672. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Chen C-Y, Chi Y-H, Mutalif RA, Starost MF, Myers TG, Anderson SA, Stewart CL, Jeang K-T. Accumulation of the inner nuclear envelope protein Sun1 is pathogenic in progeric and dystrophic laminopathies. Cell. 2012;149:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.059. Presents the unexpected finding that downregulating Sun1 in a mouse model for Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome and Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy ameliorates these nuclear envelope diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]