Abstract

Objectives

A model BisGMA/TEGDMA unfilled resin was utilized to investigate the effect of varied irradiation intensity on the photopolymerization kinetics and shrinkage stress evolution, as a means for evaluation of the reciprocity relationship.

Methods

Functional group conversion was determined by FTIR spectroscopy and polymerization shrinkage stress was obtained by a tensometer. Samples were polymerized with UV light from an EXFO Acticure with 0.1 wt% photoinitiator. A one dimensional kinetic model was utilized to predict the conversion-dose relationship.

Results

As irradiation intensity increased, conversion decreased at a constant irradiation dose and the overall dose required to achieve full conversion increased. Methacrylate conversion ranged from 64 ± 2 % at 3 mW/cm2 to 78 ± 1 % at 24 mW/cm2 while the final shrinkage stress varied from 2.4 ± 0.1 MPa to 3.0 ± 0.1 MPa. The ultimate conversion and shrinkage stress levels achieved were dependent not only upon dose but also the irradiation intensity, in contrast to an idealized reciprocity relationship. A kinetic model was utilized to analyze this behavior and provide theoretical conversion profiles versus irradiation time and dose.

Significance

Analysis of the experimental and modeling results demonstrated that the polymerization kinetics do not and should not be expected to follow the reciprocity law behavior. As irradiation intensity is increased, the overall dose required to achieve full conversion also increased. Further, the ultimate conversion and shrinkage stress that are achieved are not dependent only upon dose but rather upon the irradiation intensity and corresponding polymerization rate.

Keywords: reciprocity law, photopolymerization, dental restorative materials

Introduction

The exposure reciprocity law has been proposed based on the concept that a given property is directly dependent on its exposure dose, the product of the irradiation intensity and exposure time, but independent of the individual values of the irradiation intensity and exposure time. This concept for photochemical reactions was first introduced by Bunsen and Roscoe in 1923 1 and came to be known as the reciprocity law due to work in photography where the blackening of photographic film is indeed dependent only on the exposure dose 2. The reciprocity law has been proposed or applied to many different fields since that time, including photopolymerization reactions, photoconductance, medicine, and photodegradation, essentially any field where incident radiation is used to generate a response 3. At its heart, the reciprocity law assumes that the rate of the overall photochemically initiated process is proportional to the light intensity such that the overall amount of the process that occurs will depend only on the dose. While this is true for most primary photochemical processes (e.g., absorption) at reasonable light intensities, secondary processes do not generally observe this relationship.

In clinical dental settings, which makes extensive use of photopolymerization for a variety of applications, curing light types and intensities can vary significantly and differences are especially pronounced as newer lights such as argon ion lasers and LEDs continue to achieve higher irradiation intensities 4. Common light sources exhibit irradiation intensities ranging from several hundred milliwatts for conventional quartz halogen units up to 2000 milliwatts for modern LED units, and the initiating intensities have been relatively steadily increasing in recent times. It is common in the dental community to approximate curing using these lights based on the reciprocity law, and several studies looking at reciprocity have been performed 5. Palin and co-workers 6, 7 evaluated the degree of cure and cure depth utilizing different resin-based materials, initiators, and irradiation intensities for given doses to evaluate the validity of the reciprocity law for filled and unfilled systems. Musanje and Darvell 8 evaluated a series of commercial composites and found that different doses were required to achieve complete material properties for different irradiation intensities. Peutzfeld and Asmussen determined that degree of cure decreased with increased irradiation intensity for equivalent doses 9. In these studies, as well as others 10–15, the results and observed correlations regarding reciprocity varied depending on the type of material, the curing parameters that were utilized, and the degree of cure that was achieved during irradiation.

Inherently, as noted, the reciprocity law implies a scaling between the rate or extent of a process and its dependence on light intensity. Generally, for a given photoinitiated process, the overall rate of change of a particular species concentration in that process broadly can be assumed to scale with light intensity. Thus, for a particular species, Z, with a concentration [Z], the rate of reaction for that species, RZ is a function of its own concentration, the temperature, T, the concentration of other species in the reaction (broadly represented by [N]) and the light intensity, LI, as follows:

| (1) |

Here, f() represents an arbitrary function that describes the process that is occurring and a represents an exponent indicating the functional scaling of the targeted rate on light intensity. For a = 1, the process would be linear and the rate of the reaction would be proportional to the light intensity. When a = 1 and the function f is a constant over time, then equation (1) above can be integrated to find

| (2) |

where t represents the exposure time. For this unique case when the scaling exponent a = 1, it is clear that the final concentration of the reactant or product Z does not depend independently on either the light intensity or exposure time. Rather, the amount of reaction that has occurred depends only on the total dose – hence the concept of reciprocity in which whenever the product of light intensity and time are constant (i.e., a constant light dose), then the overall amount of reaction that occurs will also be a constant. Thus, it is clear from this basic analysis that there are indeed processes for which the reciprocity law will apply – those processes which exhibit first order scaling dependence on light intensity.

Primary photochemical reactions are those that follow directly from the absorption of a photon such as photoinduced cyclization of cinnamates, initiator cleavage, some photodegradation reactions, photoisomerization, and several others. Most of these primary photochemical reactions (including the blackening of photographic film for which the reciprocity law was originally proposed) indeed exhibit first order scaling and thus would be expected to follow the reciprocity law. In contrast, any reaction that is not first order in light intensity, such as radical polymerizations and many other secondary reactions that occur subsequent to the primary photochemical processes, will not follow the reciprocity law over any significant range of reaction conditions and light doses as they inherently are non-linear in their dependence on light intensity.

While the assumption of reciprocity has been utilized in the polymerization of dental materials, from a fundamental view, the assertion that conversion or any property of a photopolymer system should be directly related to dose is flawed. For classical isothermal radical photopolymerizations, under the assumptions of pseudo steady state and bimolecular radical termination, the polymerization rate can be expressed as:

| (3) |

where Rp is the rate of polymerization (i.e., the disappearance of reactive methacrylate double bonds), kp is the propagation kinetic parameter, [M] is the concentration of reactive groups, LI is the irradiant light intensity, [I] is the concentration of photoinitiator, and kt is the termination kinetic parameter 16. From this relationship, it is seen that the polymerization rate is dependent on irradiation intensity to the ½ power, which is in contrast to first order dependence that would be necessary for the reciprocity law to hold. The ½ order dependence on irradiation intensity is resultant from the termination mechanism and specifically, the assumption of biomecular radical termination 16. In practice, there are several mechanisms that lead to radical termination, and the prediction of ½ order dependence on light intensity is not always accurate 17–24.

Numerous studies have been performed to investigate the polymerization kinetics of the highly crosslinked dimethacrylate based resin systems that are utilized in dental restorative materials. These studies have demonstrated that polymerization rates scale with initiation rates (Ri) (where Ri α LI[I]) to a power that can vary from 0.3 – 0.6 18–24. Specifically, for the BisGMA/TEGDMA based systems utilized in many dental materials, polymerization rate scaling that is close to the idealized ½ power has been observed 25, 26. These investigations demonstrate that the reciprocity law, which requires first order dependence, would not be expected to hold for photopolymerization kinetics of dimethacrylate based resins.

In addition to understanding how the initiation rates affect polymerization rates, it is also important to understand the effect that polymerization kinetics have on overall conversions and material properties. In photopolymerizations, it is well known that increased irradiation intensity results in increased functional group conversions 27–29. Several investigations specific to dental materials have also shown that increased conversion is achieved with increased irradiation intensity 13, 30. However, both flexural strength and Tg were shown to be dependent only upon the ultimate conversion that is obtained and were independent of the irradiation conditions utilized to achieve those conversions 26, 31. Conversion and shrinkage stress were also evaluated with soft start curing protocols where reduced irradiation intensity profiles are utilized at the beginning of the polymerization. In these cases, even though higher overall doses of irradiation were utilized with the soft start protocol, reduced final conversions were observed 32, 33.

The focus of this study is on understanding the limitations of the reciprocity law in its application to photopolymerization reactions through a combination of experimental measurements and kinetic modeling. Model BisGMA/TEGDMA formulations were characterized for conversion and shrinkage stress as a continuous function of irradiation time and overall dose. A kinetic model is also utilized to demonstrate conversion profiles versus irradiation time and overall dose. We hypothesize that both the experimental and modeling results will demonstrate that the reciprocity law incorrectly predicts results in the model dimethacrylate formulation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The monomers bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) and triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) were donated from Esstech as a preformulated mixture with a 50/50 weight ratio. 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (Irgacure 651) was donated from BASF. All materials were used as received.

Methods

Photopolymerization of samples was conducted utilizing 0.1 wt% 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone. Irradiation intensities from dental curing units are set and cannot easily be manipulated in conjunction with analytical experiments. Hence, in order to perform a controlled study at varying irradiation intensities, samples were irradiated with shutter-controlled ultraviolet light from a mercury arc lamp (EXFO Acticure; Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) with a narrow band 365 nm filter that allowed irradiance and exposure times to be varied over wide ranges. Irradiation intensity was measured at the sample surface level with a radiometer (International Light, Model IL1400A, with a SEL 005 detector; Newburyport, MA).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

An FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet 6700; Madison, WI) equipped with a KBr beam splitter, InGaAs detector, and a front fiber port was used for collecting conversion data. Series scans were recorded at a rate of approximately two scans per second until the reaction was complete, as indicated by the functional group absorption peak no longer decreasing. The conversion of reactive double bonds was monitored for samples between glass slides at a thickness of approximately 1 mm using the change in the area of the first overtone of the methacrylate peak in the near IR region at 6170 cm−1. For each condition, experiments were performed in triplicate.

Shrinkage Stress

Experiments were performed with a tensometer (American Dental Association Health Foundation), which monitors stress development using cantilever beam deflection theory 34. Simultaneous conversion measurements were obtained using near-IR transmitted through the specimen via 1.0 mm fiber optic cables from the fiber port on the FTIR. Specimens were placed between 6 mm diameter glass rods with methacrylate silane treated ends with a thickness of 1 mm. The curing light was transmitted through the lower glass rod with exit irradiance intensity measured coincident with the sample position. For each condition, experiments were performed in triplicate.

Model

A one dimensional kinetic model was utilized that accounts for heat and mass transfer, irradiation intensity and temperature, as well as changes to kinetic parameters and diffusion with free volume. The kinetic model has been previously described in detail 25, 35, 36 and is based on radical polymerization mechanisms for initiation, propagation, and termination.

Initiation (where I is the initiator, hv is irradiation, R• are primary radicals, M is monomer, and P1• is a polymeric radical of chain length 1)

I + hv → 2R•

R• + M → P1•

Propagation (where Pn• and Pn+1• are polymeric radicals of chain length n and n+1)

Pn• + M → Pn+1z

Termination (where Pm• is a polymeric radical of chain length m)

Pn• + Pm• → Polymer

R• + Pn• → Polymer

The model accounts for the Arrhenius temperature dependence of the kinetic parameters, diffusion-controlled kinetics, termination by reaction diffusion, mass transfer and inhibition of oxygen, and the non-isothermal character of the polymerization associated with the reaction enthalpy. Fractional free volume of the polymerizing mixture is used to describe the kinetic constants and diffusion in the sample.

In these equations kp0 and kt0 are the pre-exponential factors, and Ep and ET are the activation energies for propagation and termination. fcp and fct are the critical fractional free volumes for propagation and termination. Ap and AT are the terms which determine the rate at which the kinetic constant decreases when diffusion controlled. The ideal gas constant R, temperature T, reaction diffusion parameter Rrd, and local double bond concentration [cm], are the remaining terms. Previous work was used as the basis for determining the values for the kinetic parameters 25, 37 for a 1:1 mixture of BisGMA:TEGDMA.

Results

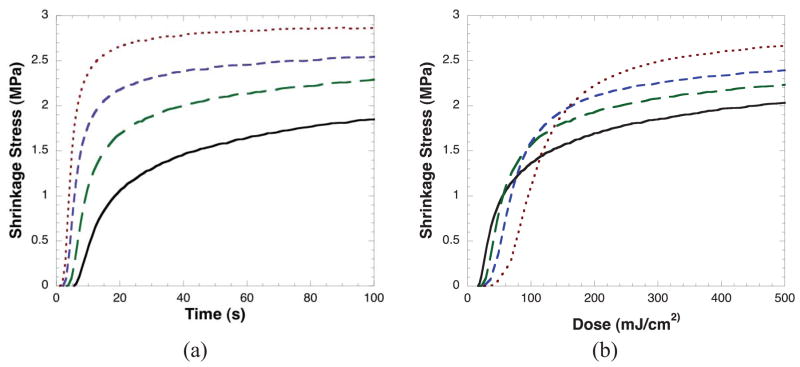

To demonstrate the effects of varying light intensity, the conversion versus time for a BisGMA/TEGDMA system cured at different irradiation intensities is shown in Figure 1a. As the irradiation intensity is increased, the polymerization rates and final conversions also increase. While this result is expected, it is interesting to view the data in terms of conversion versus dose as seen in Figure 1b. Here, instead of plotting conversion versus irradiation time, conversion is plotted against the total dose (where dose = Irradiation time*Irradiation intensity). Note, when plotting in this manner increased imprecision in the data will be more pronounced for higher irradiation intensities. If a reciprocity relationship were valid for this system, conversion would be observed to be only a function of dose, and the conversion values for each of the different irradiation conditions would be nearly identical with the conversion curves essentially falling on top of each other. However, as seen in Figure 1b, the conversion values vary significantly versus dose, with conversions being achieved more rapidly versus dose with lower irradiation intensities.

Figure 1.

Conversion versus a) time and b) dose (irradiation intensity*time) for BisGMA/TEGDMA at irradiation intensities of 3 (—), 6 (— —), 12 (– – –), and 24 (---) mW/cm2. Samples contain 0.1 wt% DMPA and are irradiated with 365 nm UV light.

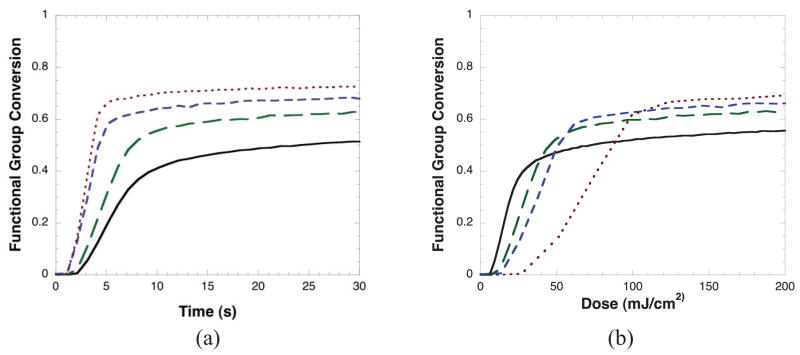

The shrinkage stress development versus dose results follow nearly identically with the conversion results. Shrinkage stress versus time at varying irradiation intensities is shown in Figure 2a. When plotted versus time, higher irradiation intensity results in more rapid and higher overall stress development. In Figure 2b, shrinkage stress is plotted versus dose. Similar to the results seen for conversion in Figure 1b, shrinkage stress development varies significantly versus dose with shrinkage stress developing more rapidly versus dose at lower irradiation intensities, but resulting in greater final shrinkage stress for the higher irradiation intensities. In Table 1, the data is summarized giving the final conversion, final shrinkage stress, and the dose required to achieve 95 % of final conversion for each of the different conditions. As the light intensity increased from 3 to 24 mW/cm2, the final methacrylate conversion that is achieved increases from 64 ± 2 % to 78 ± 1 %, the final shrinkage stress increases from 2.4 ± 0.1 to 3.0 ± 0.1 MPa, and the dose required to achieve 95 % of final conversion increases from 790 ± 50 (263 seconds at 3 mW/cm2) to 2300 ± 100 mJ/cm2 (96 seconds at 24 mW/cm2) as the light intensity increased.

Figure 2.

Shrinkage stress versus a) time and b) dose (irradiation intensity*time) for BisGMA/TEGDMA at irradiation intensities of 3 (—), 6 (——), 12 (– – –), and 24 (---) mW/cm2. Samples contain 0.1 wt% DMPA and are irradiated with 365 nm UV light.

Table 1.

Ultimate conversion, ultimate shrinkage stress, and dose required to achieve 95 % of final conversion for BisGMA/TEGDMA samples irradiated at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mW/cm2 that contain 0.1 wt% DMPA and are irradiated with 365 nm UV light for 10 min.

| Irradiation Intensity (mW/cm2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | |

| Conversion (%) | 64 (2)a | 72 (1)b | 76 (3)c | 79 (1)c |

| Shrinkage Stress (MPa) | 2.4 (0.1)a | 2.6 (0.1)b | 2.7 (0.1)b | 3.0 (0.1)c |

| Dose required to achieve 95% of final conversion (mJ) | 790 (50)a | 1000 (170)a | 1300 (300)b | 2300 (100)c |

Superscript letters in each row refer to statistically significant groupings based on one-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls pairwise multiple comparison at p < 0.05.

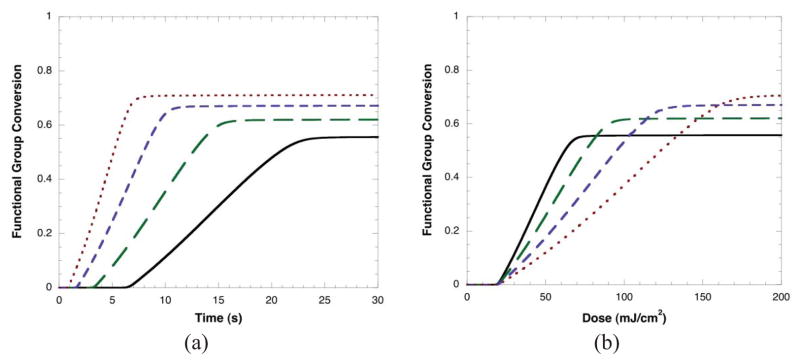

Utilizing the computational model, conversion versus time and dose are calculated for the same irradiation intensities as in Figure 1. Results are shown in Figure 3a where it is seen that the modeling results accurately reproduce the experimental trends with the expected result that higher irradiation intensities lead to more rapid polymerization rates and increased conversion. When conversion is plotted versus dose (Figure 3b), higher irradiation intensities initially require additional dose to achieve the same conversion but ultimately result in higher overall conversion. This consistency between model and experimentation demonstrates that the observed results are in agreement with the known radical photopolymerization mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Predicted conversion as a function of time and dose (irradiation intensity*time) for a range of different irradiation intensities: 3 mW/cm2 (—), 6 mW/cm2 (— —), 12 mW/cm2 (– – –), and 24 mW/cm2 (---). Kinetic parameters are based on a BisGMA:TEGDMA mixture 25, 37.

The model parameters can be modified easily to give an efficient method to probe the conditions under which reciprocity-like behavior would be observed. In the model, the change in concentration of active radical species is considered as:

| (3) |

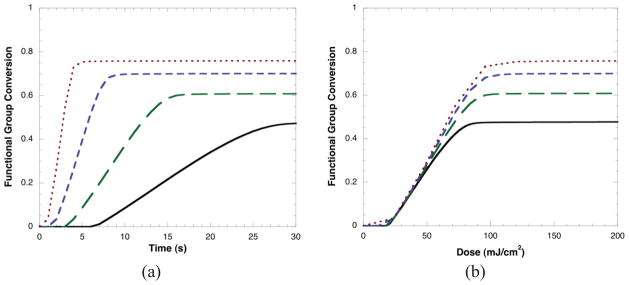

where [M•] is the concentration of radicals, kt is the bimolecular termination kinetic parameter, kO2 is the oxygen termination kinetic parameter, and [O2] is the concentration of oxygen. To bring about a more direct dependence of dose on conversion, the termination reaction must be dependent on the radical concentration to the first power. In this manner, the overall polymerization rate, which is proportional to the radical concentration, would scale with the light intensity. Thus, for the last term in equation (3) to become dominant, bimolecular termination would need to be eliminated. When kt is set to near zero to simulate this effect, the polymerization kinetics become consistent with reciprocity law behavior. However, due to the reduced rate of termination the polymerization rates become extremely rapid (Figure 4a). Under this non-physical scenario, when conversion is plotted as a function of dose (Figure 4b), the results indicate what would be expected if reciprocity was indeed to be observed, showing significant overlap as a function of dose for the different irradiation intensities. Another condition that would give rise to reciprocity is the case where the primary mechanism for termination is unimolecular (i.e., the rate of termination is kt[M•]). Using this expression for termination in the kinetic equations also results in a system that exhibits reciprocity. In these results, increasing the light intensity again yields a faster rate, although in this case the difference is even more pronounced due to first order scaling of polymerization rate with irradiation intensity (Figure 5a). Additionally, a reciprocity relationship is observed with a direct dependence of conversion on the dose (Figure 5b).

Figure 4.

Predicted conversion as a function of time and dose (irradiation intensity*time) for a range of different irradiation intensities: 3 (—), 6 (——), 12 (— —), and 24 (---) mW/cm2. Kinetic parameters are based on a BisGMA:TEGDMA mixture 25, 37 with kt reduced by 104.

Figure 5.

Predicted conversion as a function of time and dose (irradiation intensity*time) for a range of different irradiation intensities: 3 (—), 6 (---), 12 (——), and 24 (— —) mW/cm2, assuming a unimolecular termination mechanism (Rt=kt[M•]) to bring about the reciprocity law. Kinetic parameters are based on a BisGMA:TEGDMA mixture 25, 37.

Discussion

The higher conversion that is achieved versus dose at lower irradiation intensities (Figures 1 and 2) arises because at lower light intensities, each photon that is absorbed by the sample is actually used more effectively and leads to more polymerization. This phenomenon can be understood from review of the polymerization rate expression (Equation 1) where the polymerization rate (Rp) is proportional to the initiation rate (LI[I]) to the ½ power. This relationship is resultant from the classical bimolecular termination mechanism given in Equation 3 and validated by experimental data. With bimolecular termination where the termination rate is second order dependent on radical concentration, lower irradiation intensity results in a reduced concentration of radicals. The lower radical concentrations at low light intensities mean that propagation is favored over termination, allowing each radical that is formed (where the total concentration of radicals formed will be nearly proportional to the light dose) to react with more double bonds prior to termination. Thus, while the number of radicals generated does indeed scale linearly with the light intensity, the polymerization rate, which dictates the changes in conversion and cure extent, does not. At higher irradiation intensities there is a higher concentration of radicals and the average radical lifetime is decreased. Hence, on average there is a lower amount of propagation per radical. The result of these differences in average radical lifetimes is that at lower irradiation intensities more conversion is observed at a given dose than at higher irradiation intensities.

Conversely, the ultimate conversions that are attained are greater for higher irradiation intensities, due to the higher effective curing temperatures achieved at the higher light intensities resultant from the exothermic nature of the polymerization. This phenomenon is well known, is verified by the modeling results, and has been previously reported in literature 26–29, 38. At higher polymerization rates, heat is generated more rapidly which increases the temperature of the sample and delays the onset of vitrification until higher conversions, resulting in increased overall conversion. A system that is polymerizing more rapidly develops stress more rapidly; and a system that achieves higher conversions, leading to increased modulus and shrinkage, would be expected to develop an overall greater amount of stress as is observed in Figure 2. The shrinkage stress development results are consistent with previous work that has evaluated shrinkage stress versus conversion 32, 33.

It is worth noting that defined curing protocols typically provide for specific irradiation doses rather than the continuous irradiation doses shown in Figure 2. For doses that achieve less than full conversion, additional curing after cessation of irradiation occurs to some extent and hence the conversions achieved in Figure 2 would be higher than the given values if the light were extinguished at discrete points. The data analysis here demonstrates that determination of irradiation dose needs to take into consideration actual polymerization rate scaling as estimations based on reciprocity often result in significant discrepancies.

The experimental and modeling results demonstrate the effect that varying irradiation conditions can have on both conversion and property development versus dose. Initially, higher conversions are obtained at lower irradiation intensities for the same dose (Figures 1b and 3b), and this behavior also corresponds to increased shrinkage stress development (Figure 2b). As the polymerization continues, the increased polymerization rates at higher irradiation intensities result in greater temperatures resulting in increased overall conversions that drive increased shrinkage stress. These results clearly demonstrate that with varied irradiation conditions, the same overall dose can result in significantly different conversions and shrinkage stress development. When the termination mechanism is manipulated, both of the different manipulations on the termination mechanism serve to demonstrate that the validity of the reciprocity law is dependent entirely on how the polymerization rate scales with the light intensity. Only for scenarios in which the polymerization rate scales with the light intensity to the first power will reciprocity be observed.

Conclusion

Modeling and experimental results were utilized to demonstrate the effects of irradiation intensity and dose on the polymerization kinetics and shrinkage stress development in a model BisGMA/TEGDMA system. The results upheld the hypothesis and demonstrated that this photocurable resin system does not and should not be expected to follow reciprocity behavior. As the irradiation intensity is increased, the overall dose required to achieve full conversion is also increased and this polymerization behavior is resultant from the dominant bimolecular termination mechanism for free radical polymerizations. The results also demonstrate that the ultimate conversions that are achieved as well as the ultimate shrinkage stress values are not dependent upon dose, but rather are dependent on the irradiation intensity and the corresponding polymerization rate.

Acknowledgments

The I/UCRC for Fundamentals and Applications of Photopolymerizations and NIH/NIDCR Grant DE018233-0142 are gratefully acknowledged for funding this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bunsen RW, Roscoe HE. Photochemical Studies. Ann Phys. 1923;108:193. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan RH. Reciprocity law failure in X-ray films. Radiology. 1944;42:471. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin JW, Chin JW, Nguyen T. Reciprocity law experiments in polymeric photodegradation: a critical review. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2003;47:292–311. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rueggeberg FA. State-of-the-art: Dental photocuring-A review. Dental Materials. 2011;27:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leprince JG, Palin WM, Hadis MA, Devaux J, Leloup G. Progress in dimethacrylate-based dental composite technology and curing efficiency. Dental Materials. 2013;29:139–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leprince JG, Hadis M, Shortall AC, et al. Photoinitiator type and applicability of exposure reciprocity law in filled and unfilled photoactive resins. Dental Materials. 2011;27:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadis M, Leprince JG, Shortall AC, et al. High irradiance curing and anomalies of exposure reciprocity law in resin-based materials. Journal of Dentistry. 2011;39:549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musanje L, Darvell BW. Polymerization of resin composite restorative materials: exposure reciprocity. Dental Materials. 2003;19:531–41. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peutzfeldt A, Asmussen E. Resin composite properties and energy density of light cure. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:659–62. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price RBT, Felix CA, Andreou P. Effects of resin composite composition and irradiation distance on the performance of curing lights. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4465–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halvorson RH, Erickson RL, Davidson CL. Energy dependent polymerization of resin-based composite. Dental Materials. 2002;18:463–69. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(01)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halvorson RH, Erickson RL, Davidson CL. An energy conversion relationship predictive of conversion profiles and depth of cure for resin-based composite. Operative Dentistry. 2003;28:307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emami N, Soderholm KJM. How light irradiance and curing time affect monomer conversion in light-cured resin composites. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2003;111:536–42. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-8836.2003.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazaki M, Oshida Y, Moore BK, Onose H. Effect of light exposure on fracture toughness and flexural strength of light-cured composites. Dental Materials. 1996;12:328–32. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(96)80042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng L, Suh BI. Exposure reciprocity law in photopolymerization of multi-functional acrylates and methacrylates. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2007;208:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odian G. Principles of Polymerization. 3. New York: Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leprince JG, Lamblin G, Devaux J, et al. Irradiation Modes’ Impact on Radical Entrapment in Photoactive Resins. Journal of Dental Research. 2010;89:1494–98. doi: 10.1177/0022034510384624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anseth KS, Wang CM, Bowman CN. Kinetic Evidence of Reaction-Diffusion during the Polymerization of Multi(Meth)Acrylate Monomers. Macromolecules. 1994;27:650–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anseth KS, Wang CM, Bowman CN. Reaction Behavior and Kinetic Constants for Photopolymerizations of Multi(Meth)Acrylate Monomers. Polymer. 1994;35:3243–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berchtold KA, Hacioglu B, Lovell L, Nie J, Bowman CN. Using changes in initiation and chain transfer rates to probe the kinetics of cross-linking photopolymerizations: Effects of chain length dependent termination. Macromolecules. 2001;34:5103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berchtold KA, Lovell LG, Nie J, Hacioglu B, Bowman CN. The significance of chain length dependent termination in cross-linking polymerizations. Polymer. 2001;42:4925–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook WD. Photopolymerization Kinetics of Oligo(Ethylene Oxide) and Oligo(Methylene) Oxide Dimethacrylates. Journal of Polymer Science Part a-Polymer Chemistry. 1993;31:1053–67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kloosterboer JG, Lijten GFCM. Thermal and Mechanical Analysis of a Photopolymerization Process. Polymer. 1987;28:1149–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anseth KS, Kline LM, Walker TA, Anderson KJ, Bowman CN. Reaction-Kinetics and Volume Relaxation during Polymerizations of Multiethylene Glycol Dimethacrylates. Macromolecules. 1995;28:2491–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott JE, Lovell LG, Bowman CN. Primary cyclization in the polymerization of bis-GMA and TEGDMA: a modeling approach to understanding the cure of dental resins. Dental Materials. 2001;17:221–29. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovell LG, Newman SM, Donaldson MM, Bowman CN. The effect of light intensity on double bond conversion and flexural strength of a model, unfilled dental resin. Dental Materials. 2003;19:458–65. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decker C. Photoinitiated Curing of Multifunctional Monomers. Acta Polymerica. 1994;45:333–47. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kloosterboer JG. Network Formation by Chain Crosslinking Photopolymerization and Its Applications in Electronics. Advances in Polymer Science. 1988;84:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kloosterboer JG, Lijten GFCM. Chain Cross-Linking Photopolymerization of Tetraethyleneglycol Diacrylate - Thermal and Mechanical Analysis. Acs Symposium Series. 1988;367:409–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohbauer U, Rahiotis C, Kramer N, Petschelt A, Eliades G. The effect of different light-curing units on fatigue behavior and degree of conversion of a resin composite. Dental Materials. 2005;21:608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovell LG, Lu H, Elliott JE, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. The effect of cure rate on the mechanical properties of dental resins. Dental Materials. 2001;17:504–11. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(01)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu H, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Probing the effect of curing conditions on shrinkage stress development and polymerization kinetics. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society. 2003;226:U432–U32. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu H, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Impact of curing protocol on conversion and shrinkage stress. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:822–26. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Stansbury JW, Dickens SH, Eichmiller FC, Bowman CN. Probing the origins and control of shrinkage stress in dental resin-composites: I. Shrinkage stress characterization technique. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 2004;15:1097–103. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSM.0000046391.07274.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodner MD, Bowman CN. Development of a comprehensive free radical photopolymerization model incorporating heat and mass transfer effects in thick films. Chemical Engineering Science. 2002;57:887–900. [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Brien AK, Bowman CN. Modeling thermal and optical effects on photopolymerization systems. Macromolecules. 2003;36:7777–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott JE, Bowman CN. Monomer functionality and polymer network formation. Macromolecules. 2001;34:4642–49. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye S, Cramer NB, Bowman CN. Relationship between Glass Transition Temperature and Polymerization Temperature for Cross-Linked Photopolymers. Macromolecules. 2011;44:490–94. [Google Scholar]