Abstract

Many epidemiological reports indicate that Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection plays an important role in gastric carcinogenesis. Several genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute to the initiation, promotion, and progression of the cancer cells in a multi-step manner. H pylori is known to induce chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa. Its products, including superoxides, participate in the DNA damage followed by initiation, and the inflammation-derived cytokines and growth factors contribute to the promotion of gastric carcinogenesis. By eradicating H pylori, gastric inflammation can be cured; the therapy diminishes the levels not only of inflammatory cell infiltration, but also atrophy/intestinal metaplasia in part. A randomized controlled trial revealed that the eradication therapy diminished the gastric cancer prevalence in cases without pre-cancerous conditions. In addition, recent epidemiological studies from Japanese groups demonstrated that the development of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type, was decreased by successful eradication therapy, although these were designed in a non-randomized manner. However, it should be mentioned that endoscopic detection is the only way to evaluate the degree of gastric carcinogenesis. We have reported that the endoscopic and histological morphologies could be modified by eradication therapy and it might contribute to the prevalence of gastric cancer development. Considering the biological nature of cancer cell proliferation, it is considered that a sufficiently long-term follow-up would be essential to discuss the anticancer effect of eradication therapy.

Keywords: H pylori, Eradication, Gastritis, Gastric neoplasm, Endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H pylori), a Gram-negative bacillus discovered in 1983, is the most popular pathogenic bacteria in the world. Approximate-ly half of the popula-tion has H pylori infection worldwide, and the prevalence is thought to be 80 - 90% in developing countries and 30 - 50% in developed countries[1]. Many studies clarified the implication of the bacteria as the cause of many gastroduodenal diseases, including histological chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, and mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma[2,3].

In particular, histological chronic atrophic gastritis is an important disease for gastric carcinogenesis. Two main causes for the promotion of atroph-ic gastrit-is are (1) H pylori and (2) autoimmune factors such as antiparietal cell antibody. Although these two factors work synergistically in the promotion of atrophic gastritis[4,5], autoimmune gastritis is a rare disease and most atrophic gastritis is thought to be induced by H pylori infection in East-Asian countries such as in Japan, China, and Korea[6]. Therefore, it is likely that H pylori is the most important factor for mucosal atrophy and we have confirmed this hypothesis in the Japanese population[7].

Gastric cancer is the second most common cancer (next to lung cancer) in the world and the number of newly diagnosed cases was calculated as 7 50 000 persons per year[8]. As previously demonstrated by Correa et al., atrophic gastritis and the following intestinal metaplasia are regarded as an essential status for intestinal type cancer development[9]. It has been widely accepted that there is a strong association between H pylori-associated gastritis and gastric cancer. Nomura et al. and Parsonnet et al. first reported the relationship between H pylori infection and gastric cancer in 1991[10,11]. In 1994, the International Center for Cancer Research officially recogniz-ed that H pylori was a definite carcinogen for gastric cancer on the basis of several epidemiological reports[12]. Moreover, Huang et al. demonstrated the relationship between H pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer by meta-analysis[13]. The odds ratios for gastric cancer were calculated as 1.92 (1.32 - 2.78; 95%CI), 2.24 (1.15 - 4.4), and 1.81 (1.16 - 2.84) for all studies, cohort and case-control studies, respectively. In addition, many investigations showed the tight relationship between H pylori and not only intestinal type cancer, but also diffuse type cancer[13,14]. Even in gastric cancer at a younger age, we were able to detect a tight relationship between gastric cancer and H pylori[15]. In 2001, Uemura et al.[16] clearly demonstrated that gastric cancer developed only in patients with H pylori infection with a prospective study. They prospectively followed 1 246 Japanese people for 7.8 years and found that gastric cancer had been detected in only 36 patients with H pylori infection. No gastric cancer was found in H pylori-negative patients in their study.

These findings strongly suggest the implication of H pylori in gastric carcinogenesis. Next, we should clarify the hypothesis as to whether we can control gastric carcinogenesis by the eradication of H pylori. In the present study, we have summarized the recent clinical evidence in this field and have attempted to answer this question.

Gastric inflammation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection and its carcinogenic effects

Persistent infection of H pylori induces the characteristic inflammation in the gastric mucosa with the histological finding of mononuclear cell/neutrophil infiltration. In particular, the superoxides, such as nitric oxide, in the gastric mucosa play an important role in the initiation of the carcinogenesis as a mediator of carcinogenic nitrosamine formation, DNA damage and tissue injury. Studies have also revealed that H pylori infection in human beings is associated with the enhanced expression of iNOS by tissue neutrophils and mononuclear cells[17,18]. Previously, we have reported that the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in chronic gastritis is a predictive marker for a high risk of gastric cancer development[19]. The iNOS-producing gastritis, which is supposed to be strongly associated with gastric cancer, showed a characteristic cytokine profile and serum gastrin pattern[20].

Chronic inflammation results in the destruction of parietal cells of the oxyntic gland in the gastric corpus followed by the alteration of the pathophysiological status, including gastric acid secretion[21]. The pH of gastric juice is a major determinant of the nitrite and vitamin C concentrations in gastric juice. Previous studies reported a close linkage between low acid output and an increased concentration of nitrite and N-nitroso compounds in gastric juice[22]. Vitamin C was actively secreted into gastric juice and scavenges nitrite from the gastric juice and thereby acts to prevent the formation of nitrosamines. Vitamin C concentrations in gastric juice were found to be low in patients with hypochlorhydria status[23]. In addition, we have reported that gastric juice nitrite concentrations are higher and vitamin C concentrations are lower in patients with gastric cancer than those in atrophic gastritis, despite similar intra-gastric pH and H pylori status[24].

Furthermore, inflammation-derived cytokines and growth factors are known to act as promotion/proliferation factors for gastric cancer cells. Especially, hepatocyte growth factor has been reported to play a crucial role in epithelial/tumor cell proliferation, and its expression was promoted in H pylori-infected mucosa[25]. Churin et al. reported that H pylori activated c-Met (the receptor of HGF) in AGS cells, suggesting the important role of HGF in an autocrine manner[26]. In addition, the regulation of apoptotic signals is another important factor for the promotion/proliferation of cancer cells. H pylori was reported to be able to induce apoptosis of the gastric epithelial cells directly[27]. Nagasako et al.[28] have demonstrated that the Smad-5, which contributes to the apoptosis of gastric epithelial cells, is upregulated by H pylori infection.

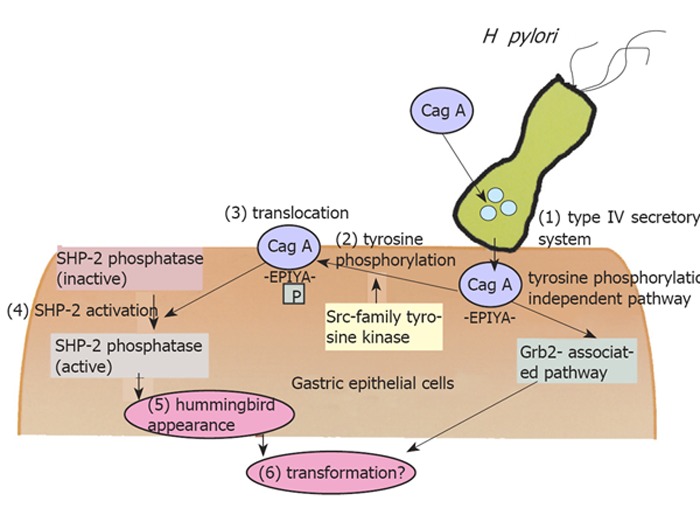

Many recent advances have revealed the detailed molecular mechanisms of gastric inflammation induced by H pylori. The research on some virulent bacterial factors, VacA and CagA, were reported successively from Japanese groups. Fujikawa et al.[29] clarified that VacA binds to protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z (Ptprz), which is a specific receptor on epithelial cells, and induces the intracellular pathway via G protein-coupled receptor kinase-interactor 1 (Git1) and pleiotrophin. On the other hand, the advantage of CagA is the most sensational in this field. Previously, Huang et al.[30]demonstrated the strong association between anti-CagA seropositivity and gastric carcinogenesis, suggesting the importance of CagA for gastric carcinogenesis. CagA protein produced in the bacterial cell is translocated into the host cell by a type IV secretory system[31], followed by translocation to the membrane[32], tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motif by src-family kinase and the activation of SHP - 2 phosphatase, which is the important second messenger from CagA (Figure 1)[33]. Recent studies by Hatakeyama et al. clarified that the CagA protein showed diversity and was subclassified into two types, the Western type and East-Asian type, and the later type was reported to have a high affinity to SHP - 2 and was regarded as a more harmful form[34]. It is possible to explain the international diversity of the prevalence of gastric cancer; in Western countries, the prevalence of gastric cancer is relatively low because Western type CagA (or Cag negative strain) is dominant. On the other hand in East-Asian countries, the more virulent strain (East-Asian type) is the major strain, and this is a reason for the higher prevalence of gastric cancer. However, it is still unclear why some Japanese/Chinese people do not show corpus atrophy, even if they carry the East-Asian type CagA. Mimuro et al.[35]suggested another signal pathway via growth factor receptor bound 2(Grb2), which is independent of CagA phosphorylation. Intragastric diversity or other bacterial factors must be examined to solve this question, as well as the host factors and environmental factors including a high intake of salt[36].

Figure 1.

Intracellular molecular pathway starting from H pylori infection.

After successful H pylori eradication therapy, these harmful conditions are dramatically improved. There is no doubt that the eradication therapy can diminish the risk of the new development of gastric cancer or progression from the pre-malignant status. However, it should be emphasized that it takes a long time from when one cell transforms into a cancer cell to when we can detect the cancer tissue by endoscopic examination. Although the growth rate of gastric cancer cells differs according to their biological or histological characteristics, Haruma et al.[37] reported that average doubling time of early gastric cancer is 16.6 mo in the polypoid type. From this fact, it is likely that when we detect the cancer lesion in the stomach by endoscopic examination, cancer cells must have already been present for many years, even if it is not detectable. Cancer cells have progressed through the multi-step process of genetic and epigenetic alteration of oncogenes[38]. These alterations must occur in the cancer cells in the initial stage, and it is unlikely that these could be always cancelled by eradication therapy alone.

Reversibility of pre-malignant status; atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia

Many reports have mentioned the improvement of neutrophil/lymphocyte infiltration after H pylori eradication therapy. However, it is still controversial as to the improvement of glandular atrophy or intestinal metaplasia after the eradication therapy. Annibale et al. have concluded that eradication therapy does not improve mucosal atrophy[39]. Sung et al.[40] reported the results of a large-scale prospective randomized study and concluded that eradication therapy prevents the progression of atrophy, which was not reversible. However, some problems remain that the following period is relatively short in the former, and the basal grades of atrophy were mild in the latter study. On the other hand, Ohkusa et al.[41] and Haruma et al.[42] enrolled patients with atrophic gastritis and reported the reversibility of atrophy after H pylori eradication therapy,. Furthermore, we previously followed up 22 patients in whom H pylori was eradicated for 5 years and confirmed that glandular atrophy is reversible both in the gastric corpus and in the antrum[43]. It should be noted that the reversibility of atrophy was found in the patients with moderate atrophy, and it took a long-time to confirm the reversibility. In cases with complete disappearance of the gland, such as cases with gastric adenoma, reconstruction of the gland may be unlikely. Recently, Sugiyama et al.[44] reported the regression of corpus atrophy after eradication. They emphasized the importance of the biopsy site, and demonstrated that the most suitable point is the lesser curvature of the gastric corpus.

Another major problem is the reversibility of the intestinal metaplasia. Although some reports have refuted the improvement of intestinal metaplasia[39,45], there has been a report suggesting the effect of eradication therapy in the improvement of intestinal metaplasia[41]. Correa et al.[46] reported that eradication therapy could regress not only the degree of atrophy, but also the intestinal metaplasia in a randomized controlled trial. Leung et al.[47] demonstrated that the eradication therapy could prevent the progression of intestinal metaplasia using a randomized controlled trial with a 5-year follow-up. However, to evaluate the status of intestinal metaplasia, biopsy specimens for point-diagnosis seem to be not suitable. Therefore, we performed dye-endoscopy using methylene blue solution, which allowed us to evaluate the degree of intestinal metaplasia as a “field”. Our overall results suggested the reversibility of intestinal metaplasia by following up over long periods, even if all patients did not show a regression of the intestinal metaplasia[43]. At present, a large-scale prospective study (Japanese intervention trial of H pylori) has been ongoing. In this study, the reversibility of atrophic gastritis was examined by endoscopic and histological examinations, and its final result will be published in 2006. Although the improvement of atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia links to the regression of gastric carcinogenesis at the extremely early stage, a long-term (more than 10 years) follow-up study will be necessary to confirm the effect of eradication therapy on gastric carcinogenesis.

Does eradication therapy truly diminish gastric cancer

It is clinically important to clarify whether gastric carcinogenesis could be influenced by eradication therapy. Firstly, Uemura et al.[48] reported the reduced incidence of secondary developed gastric cancer by eradication therapy in patients with endoscopic resection of the primary gastric cancer. Because of the reason described above, their data did not suggest an anticarcinogenic effect of the eradication therapy, but instead an antiproliferative effect of cancer cell growth. Indeed, we have previously reported that the Ki - 67 labeling index in cancer cells is lower in cancer lesions without H pylori infection than in those with H pylori[49]. Recently, Take et al.[50] reported that they followed up 1 120 peptic ulcer patients with eradication therapy prospectively (mean 3.4 years) and found that gastric cancer is more frequently detected in patients with failed eradication than those with successful eradication. They have also demonstrated that gastric cancer was never detected in duodenal ulcer patients, in whom atrophic gastritis should be absent. On the other hand, a Chinese group has demonstrated, with a randomized controlled trial, that there is a relative decrease in cancer incidence in patients with eradication therapy in the overall population, but this difference did not reach a level of significance[51]. Only in a subgroup without pre-cancerous lesions (without atrophy or intestinal metaplasia) they demonstrated the statistically reduced incidence of gastric cancer by eradication therapy. These results may be partially conflicting to each other and the reason for this is uncertain. However, we should pay attention to the difference in the clinical stage of gastric cancer detected and in the diagnostic ability of endoscopic examination between both trials. Whereas, in the Japanese study, most gastric cancer lesions were detected in the early stage as an intramucosal cancer, lesions found in Chinese study were those in a more advanced stage. We could not conclude that these two studies were designed with the same method because the endpoints may be different.

Recently, Kamada et al.[52] also prospectively followed up 1 787 patients with eradication therapy (median 4.5 years) and demonstrated that gastric cancer could be detected in 20 patients (1.1%). Most cancer lesions were detected in the early stage as intramucosal cancer and its histology was intestinal type dominant (75%). We also prospectively examined 101 patients with atrophic gastritis prospectively for more than 60 mo (mean 63.2 months) and found gastric cancer incidence in 8 patients[53]. Most gastric cancers were detected in the early stage and their histologies were of the intestinal type, and this is in complete agreement with previous studies. In addition, gastric cancer is more frequently found in elderly patients than in younger patients (P < 0.05). For the patients with atrophic gastritis, the age at the time of eradication therapy is an important factor for the occurrence of cancer after successful eradication. The long-term strict follow-ups after eradication seem to be necessary in elderly patients with atrophic gastritis.

Does alteration of the tumor appearance after eradication therapy modulate the incidence of cancer discovery

As described above, the focus must be placed on the diagnostic ability of gastric cancer by endoscopic examination when we discuss the cancer discovery rate determined clinically. One of the difficulties of this field seems to be based on the methodology used to evaluate gastric carcinogenesis. Researchers can evaluate the degree of carcinogenesis only by the discovery rate of gastric cancer by endoscopic examination. Due emphasis must be placed on the differences in the diagnostic ability of each examination.

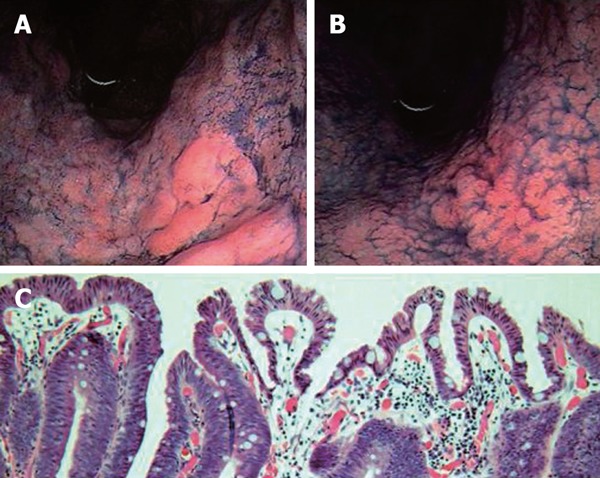

Moreover, endoscopic morphology might be influenced directly by eradication therapy, thus affecting the discovery rate of gastric cancer. Previously, Gotoda et al.[51] reported the endoscopic regression of gastric adenoma after successful eradication therapy. If the eradication itself influences the tumor morphology, this may affect the tumor discovery rate. Then, we investigated the morphological changes in the gastric neoplasm after H pylori eradication in Japanese patients. After a one-month follow-up, endoscopic re-evaluation revealed that one-third of the gastric tumor became indistinct and some tumors were difficult to discern with ordinary endoscopic observation[55]. All these altered lesions were of the superficial-elevated type, which is the characteristic appearance of intestinal type cancer, irrespective of the grade of histological appearance (adenoma or carcinoma) (Figure 2). The tumor appearance became flattened and the height of the lesions decreased, then the tumor became indistinct after eradication, even after a short time. In the depressed type cancer, that is typical for diffuse type gastric cancer, we could not find any morphological changes after eradication[55]. These results suggest that the morphology of the gastric neoplasm changes after eradication in the short-term, especially in the intestinal type gastric cancer, which were found characteristically in patients after eradication therapy. Even if the true incidence of cancer is not affected by eradication, the incidence of cancer discovery would be influenced by successful eradication therapy in cases of intestinal type cancer with elevated tumor features. Furthermore, we detected normal columnar epithelium over the neoplasm in some lesions (Figure 2). The appearance of normal foveolar epithelium must make it more difficult to detect gastric cancer by endoscopic observation. We could not explain the origin of this strange histological feature, but the most probable origin may be a regenerative change against the surface injury of the mucosal tumor tissue induced by the improved acid output after successful eradication. This must also contribute to the reduction in the rate of cancer discovery after successful eradication therapy and these overall alterations are quite rational for the explanation of the results reported by the Japanese researchers.

Figure 2.

Dye-endoscopic features of gastric adenocarcinoma at pre- (A) and post-eradication therapy (B). Tumors became flattened and indistinct after eradication therapy. Histological features of gastric neoplasm at post-eradication are demonstrated in panel (C). Patient was a 67-year-old male.

The mechanism of the antitumor promoting effect of H pylori eradication therapy is still unknown. In the in vitro studies, H pylori itself has been found to modify the expressions of several genes in gastric carcinoma cells[56]. Semino-Mora et al.[57] demonstrated the presence of H pylori-derived toxic proteins and mRNAs in gastric tumor cells in vivo. However, their theory is still controversial, and, until now, it has been believed that H pylori cannot exist in the gastric carcinoma cells. Thus, it is likely that H pylori indirectly influences tumor cell growth by regulating the inflammatory reaction around the tumor tissue. Several cytokines have been induced by H pylori infection and some of them may act as growth factors for tumor cells[25,58]. Suzuki et al [59] reported the decreased level of HGF in the gastric mucosa after eradication, which was linked to the decreased cell turnover. These indicate the importance of gastric inflammation in the gastric mucosa rather than H pylori itself on the luminal side. Gastrin is known to be an important gut-related hormone and a growth factor for gastric cancer cells, and gastric tumor cells have been shown to contain its receptor[60]. However, it is unlikely that our new findings of the morphological changes were induced by a gastrin-related system[55].

There are two ways in which gastric tumors may grow; one is invasive downward growth and the other is expansive growth in the upward (luminal) direction. The latter may include the reactive (non-neoplastic) factor, which may be regulated by the gastric inflammation induced by H pylori infection. Kamada et al.[52] analyzed the macroscopic features of gastric cancers discovered after eradication therapy and demonstrated that most lesions are of the depressed type. If the eradication therapy mainly influences the expansive growth, the true biological behavior of the gastric malignancies may not be improved by eradication therapy.

Clinical manifestations of H pylori eradication therapy and what are the problems in the next step

There is no doubt that eradication therapy diminishes the prevalence of cancer development. In the animal model with Mongolian gerbils, Shimizu et al.[61] demonstrated that H pylori eradication therapy diminishes the prevalence of gastric cancer incidence induced by H pylori infection and low-dose chemical carcinogen. Tatematsu et al.[62] also reported that H pylori eradication therapy regresses the heterotopic proliferative glands in the gastric mucosa of Mongolian gerbils, suggesting that the eradication reduces the promoting effect of the bacterium.

In human studies, we cannot discuss the anticarcino-genic effect of eradication therapy unless we follow up patients for a sufficiently long period (more than 10 years). As discussed above, it is very important that we distinguish the “development” of gastric cancer from the “discovery” of the tumor. In addition, it is clinically important to clarify whether eradication therapy can diminish the mortality rate for gastric cancer or not. It is very critical to know as to how we regress the biologically malignant gastric cancer, including diffuse-type cancer in younger patients. No reports have discussed this, and further study is necessary to answer this question.

Another problem to be solved is the “point of no return” of gastric carcinogenesis by eradication therapy. In the animal model, earlier eradication was demonstrated to be more effective for preventing the development of gastric cancer[63]. Since gastric cancer after eradication was frequently found in patients who received eradication in older age, we should consider that younger people should receive eradication therapy as early as possible. For the effective eradication for cancer prevention to be practical and economical, the selection of the population at higher risk should be clarified. It is especially necessary to identify the fundamental status of gastric inflammation in the development of diffuse type gastric cancer. Recent studies revealed that a high odds ratio for gastric cancer discovery was noticed in patients with nodular gastritis, which may be an important background for diffuse-type cancer[64,65]. This type of gastritis should be an important target for earlier eradication therapy to reduce cancer death. In addition, we should determine useful biomarkers for gastric inflammation, which would be beneficial for real clinical practice[66].

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wu M

References

- 1.Goodman KJ, Cockburn M. The role of epidemiology in understanding the health effects of Helicobacter pylori. Epidemiology. 2001;12:266–271. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH Consensus Conference. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. JAMA. 1994;272:65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claeys D, Faller G, Appelmelk BJ, Negrini R, Kirchner T. The gastric H+,K+-ATPase is a major autoantigen in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis with body mucosa atrophy. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito M, Haruma K, Kaya S, Kamada T, Kim S, Sasaki A, Sumii M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Role of anti-parietal cell antibody in Helicobacter pylori-associated atrophic gastritis: evaluation in a country of high prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:287–293. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haruma K, Komoto K, Kawaguchi H, Okamoto S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Pernicious anemia and Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: evaluation in a country with a high prevalence of infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1107–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawaguchi H, Haruma K, Komoto K, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Helicobacter pylori infection is the major risk factor for atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:959–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa P. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:238s–241s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19 Suppl 1:S37–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schistosomes , liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komoto K, Haruma K, Kamada T, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G, Talley NJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric neoplasia: correlations with histological gastritis and tumor histology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1271–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haruma K, Komoto K, Kamada T, Ito M, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Helicobacter pylori infection is a major risk factor for gastric carcinoma in young patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:255–259. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiyama A, Maruta F, Ikeno T, Ishida K, Kawasaki S, Katsuyama T, Shimizu N, Tatematsu M. Helicobacter pylori infection enhances N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced stomach carcinogenesis in the Mongolian gerbil. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2067–2069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rachmilewitz D, Karmeli F, Eliakim R, Stalnikowicz R, Ackerman Z, Amir G, Stamler JS. Enhanced gastric nitric oxide synthase activity in duodenal ulcer patients. Gut. 1994;35:1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goto T, Haruma K, Kitadai Y, Ito M, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Hayakawa N, Kajiyama G. Enhanced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in gastric mucosa of gastric cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1411–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kai H, Ito M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Chronic gastritis with expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase is associated with high expression of interleukin-6 and hypergastrinaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1309–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshihara M, Haruma K, Sumii K, Watanabe C, Kiyohira K, Kawaguchi H, Tanaka S, Kajiyama G. The relationship between gastric secretion and type of early gastric carcinoma. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 1995;44:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed PI, Smith PL, Haines K, House FR, Walters CL. Gastric juice N-nitrosamines in health and gastroduodenal disease. Lancet. 1981;2:550–552. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90939-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor HJ, Schorah CJ, Habibzedah N, Axon AT, Cockel R. Vitamin C in the human stomach: relation to gastric pH, gastroduodenal disease, and possible sources. Gut. 1989;30:436–442. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.4.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodama K, Sumii K, Kawano M, Kido T, Nojima K, Sumii M, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Gastric juice nitrite and vitamin C in patients with gastric cancer and atrophic gastritis: is low acidity solely responsible for cancer risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:987–993. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasunaga Y, Shinomura Y, Kanayama S, Higashimoto Y, Yabu M, Miyazaki Y, Kondo S, Murayama Y, Nishibayashi H, Kitamura S, et al. Increased production of interleukin 1 beta and hepatocyte growth factor may contribute to foveolar hyperplasia in enlarged fold gastritis. Gut. 1996;39:787–794. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churin Y, Al-Ghoul L, Kepp O, Meyer TF, Birchmeier W, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:249–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin JH, Potthoff A, Ledig S, Cornberg M, Jandl O, Manns MP, Kubicka S, Flemming P, Athmann C, Beil W, et al. Effect of H. pylori on the expression of TRAIL, FasL and their receptor subtypes in human gastric epithelial cells and their role in apoptosis. Helicobacter. 2004;9:371–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagasako T, Sugiyama T, Mizushima T, Miura Y, Kato M, Asaka M. Up-regulated Smad5 mediates apoptosis of gastric epithelial cells induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4821–4825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujikawa A, Shirasaka D, Yamamoto S, Ota H, Yahiro K, Fukada M, Shintani T, Wada A, Aoyama N, Hirayama T, et al. Mice deficient in protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z are resistant to gastric ulcer induction by VacA of Helicobacter pylori. Nat Genet. 2003;33:375–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asahi M, Azuma T, Ito S, Ito Y, Suto H, Nagai Y, Tsubokawa M, Tohyama Y, Maeda S, Omata M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein can be tyrosine phosphorylated in gastric epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:593–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higashi H, Yokoyama K, Fujii Y, Ren S, Yuasa H, Saadat I, Murata-Kamiya N, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. EPIYA motif is a membrane-targeting signal of Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23130–23137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Fujita A, Yamazaki S, Asaka M, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. Biological activity of the Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA is determined by variation in the tyrosine phosphorylation sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14428–14433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222375399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Tanaka J, Asahi M, Haas R, Sasakawa C. Grb2 is a key mediator of helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol Cell. 2002;10:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Inada K, Tsukamoto T, Inoue M, Kumagai T, Sugiyama A, Mizoshita T, Kaminishi M, Tatematsu M. Synergistic promoting effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and high-salt diet on gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haruma K, Suzuki T, Tsuda T, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Evaluation of tumor growth rate in patients with early gastric carcinoma of the elevated type. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:289–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01887370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tahara E. Genetic pathways of two types of gastric cancer. IARC Sci Publ. 2004:327–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Annibale B, Aprile MR, D'ambra G, Caruana P, Bordi C, Delle Fave G. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection in atrophic body gastritis patients does not improve mucosal atrophy but reduces hypergastrinemia and its related effects on body ECL-cell hyperplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung JJ, Lin SR, Ching JY, Zhou LY, To KF, Wang RT, Leung WK, Ng EK, Lau JY, Lee YT, et al. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia one year after cure of H. pylori infection: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:7–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohkusa T, Fujiki K, Takashimizu I, Kumagai J, Tanizawa T, Eishi Y, Yokoyama T, Watanabe M. Improvement in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in patients in whom Helicobacter pylori was eradicated. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:380–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-5-200103060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haruma K, Mihara M, Okamoto E, Kusunoki H, Hananoki M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases gastric acidity in patients with atrophic gastritis of the corpus-evaluation of 24-h pH monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:155–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito M, Haruma K, Kamada T, Mihara M, Kim S, Kitadai Y, Sumii M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy improves atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: a 5-year prospective study of patients with atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1449–1456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugiyama T, Sakaki N, Kozawa H, Sato R, Fujioka T, Satoh K, Sugano K, Sekine H, Takagi A, Ajioka Y, et al. Sensitivity of biopsy site in evaluating regression of gastric atrophy after Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16 Suppl 2:187–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.16.s2.17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satoh K, Kimura K, Takimoto T, Kihira K. A follow-up study of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1998;3:236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY, To KF, Ng EK, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244–1249. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasaki A, Kitadai Y, Ito M, Sumii M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Haruma K, Chayama K. Helicobacter pylori infection influences tumor growth of human gastric carcinomas. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:153–158. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Oguma K, Okada H, Shiratori Y. The effect of eradicating helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1037–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamada T, Hata J, Sugiu K, Kusunoki H, Ito M, Tanaka S, Inoue K, Kawamura Y, Chayama K, Haruma K. Clinical features of gastric cancer discovered after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: results from a 9-year prospective follow-up study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1121–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takata S, Ito M, Tanaka S, Oka S, Ueda H, Egi Y, Kai H, Sasaki A, Masuda H, Kim S, et al. Development of gastric cancer after successful eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori: By long-term prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:182A. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gotoda T, Saito D, Kondo H, Ono H, Oda I, Fujishiro M, Yamaguchi H. Endoscopic and histological reversibility of gastric adenoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34 Suppl 11:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito M, Tanaka S, Takata S, Oka S, Imagawa S, Ueda H, Egi Y, Kitadai Y, Yasui W, Yoshihara M, et al. Morphological changes in human gastric tumours after eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori in a short-term follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitadai Y, Sasaki A, Ito M, Tanaka S, Oue N, Yasui W, Aihara M, Imagawa K, Haruma K, Chayama K. Helicobacter pylori infection influences expression of genes related to angiogenesis and invasion in human gastric carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Semino-Mora C, Doi SQ, Marty A, Simko V, Carlstedt I, Dubois A. Intracellular and interstitial expression of Helicobacter pylori virulence genes in gastric precancerous intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1165–1177. doi: 10.1086/368133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Imanishi J. Helicobacter pylori cagA gene and expression of cytokine messenger RNA in gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1744–1752. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki M, Suzuki H, Masaoka T, Tanaka S, Suzuki K, Ishii H. Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment modulates epithelial cell proliferation and tissue content of hepatocyte growth factor in the gastric mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 1:158–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ochiai A, Yasui W, Tahara E. Growth-promoting effect of gastrin on human gastric carcinoma cell line TMK-1. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1985;76:1064–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inada K, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto T, Nozaki K, Kaminishi M, Kuramoto S, Sugiyama A, Katsuyama T, et al. Eradication diminishes enhancing effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on glandular stomach carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1512–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tatematsu M, Tsukamoto T, Mizoshita T. Role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinogenesis: the origin of gastric cancers and heterotopic proliferative glands in Mongolian gerbils. Helicobacter. 2005;10:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inoue M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K, Tanaka H, Kumagai T, Kaminishi M, Tatematsu M. Effect of early eradication on Helicobacter pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, Sumioka M, Nishisaka T, Tanaka S, Inoue K, Chayama K. Five cases of nodular gastritis and gastric cancer: a possible association between nodular gastritis and gastric cancer. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:819–820. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamada T, Miyamoto M, Ito M, Sugiu K, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Nagashima Y, KIDo S, Hamada H, Haruma K. Nodular gastritis is a risk factor for diffuse-type of gastric carcinoma in Japanese young patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:A456. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naito Y, Ito M, Watanabe T, Suzuki H. Biomarkers in patients with gastric inflammation: a systematic review. Digestion. 2005;72:164–180. doi: 10.1159/000088396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]