Abstract

AIM: To compare the efficacy of self-expandable metallic stents (EMS) in the treatment of distal and proximal stricture of malignant biliary tumors.

METHODS: From March 1995 to June 2004, 61 patients (40 males, 21 females) with malignant biliary obstruction who received self-expandable metallic stent implantation were reviewed retrospectively. The stents were inserted by an endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic method. We tried to place two stents in the biliary system in T or Y configuration in cases of hilar tumors with bilateral hepatic duct obstruction. The end points of the study were stent occlusion or patient death.

RESULTS: The mean time of stent patency was 421 ± 67 d in the group of proximal stricture( group I) and 168 ±18 d in the group of distal stricture (group II). The difference was significant in borderline between the two groups (P = 0.0567). The mean survival time was 574 ± 76 d in group I and 182 ± 25 d in group II. There was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.0005).

CONCLUSION: EMS implantation is a feasible, palliative method for unresectable malignant biliary obstruction. The clinical efficacy of EMS in patients with proximal hilar tumors is better than that in patients with distal tumors.

Keywords: Metallic stent, Biliary malignancy

INTRODUCTION

Biliary stent placenrent is the treatment of choice for malignant biliary obstruction caused by unresectable neoplasms[1,2].Although self-expandable metallic stents (EMS) are much more expensive than plastic stents, EMS is claimed to be superior to plastic stents in long-term stent patency[3]. At first, when EMS is uncovered, the tumor often invades the stent via meshes of the metallic stent, resulting in stent obstruction[1]. To overcome the problem of tumor ingrowth in uncovered metallic stents, covered EMS have been developed in the 1990s[1,4,5]. However, complications of covered EMS, such as cholecystitis and pancreatitis, should be noted [1,5] .

Uncovered EMS are introduced into Taiwan in the 1990s to overcome the weak points of plastic stents [2]. In our hospital, we bave begun to use uncovered EMS for the treatment of unresectable malignant biliary obstruction since 1995 and covered EMS in selective cases since 2002.

Lee et al [6] found that the clinical efficacy of EMS in patients with hilar tumor is superior in those with common bile duct obstruction. Rieber and Brambs[7] demonstrated that worse results are seen in patients with pancreatic tumors and with lymph nodes metastases of the colon and gastric cancers. We have found similar trends in our practice. Therefore, we performed this study to compare the efficacy of EMS in the treatment of distal and proximal stricture of malignant biliary tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From March 1995 to June 2004, 61 patients (40 males, 21 females) with malignant biliary obstruction who received EMS implantation were reviewed retrospectively. Neoplasms were unresectable and the diagnosis was based on pathological examination or clinical and imaging findings.

The patients received endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) initially. Plastic stent drainage, nasobiliary drainage or PTCD was set up. when the neoplasms were cnfirmed to be unresectable, the patients were assigned to insertion of EMS if they agreed. Wallstent (Schneider, Switzerland) and Ultraflex diamond stent (Microvasive; Boston Scientific Corporation, MA, USA ) were used in our patients. EMS were inserted either by therapeutic duodenoscopy (TJF 200, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan ) or by the percutaneous transhepatic approach. We tried to place two stents in the biliary system in T or Y configuration in cases of hilar tumors with bilateral hepatic duct obstruction. Covered EMS were inserted only in patients with distal stricture.

The lesions were defined as distal stricture if the tumors were located at or below the orifice of the cystic duct. The lesions were defined as proximal stricture if the tumors were located above the orifice of the cystic duct.

Stent occlusion was defined as recurrence of jaundice or cholangitis with evidence of stent stenosis requiring biliary intervention after successful insertion of EMS. The stent patency period was calculated as the time between stent placement and its occlusion or patient death. Cumulative stent patency and patient survival were evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier technique. The end points of the study were stent occlusion or patient death.

RESULTS

Patient enrollment and characteristics

Sixty-one patients were enrolled in this study. The patients were divided into two groups according to their obstruction level.

Group I (21 patients) was consisted of proximal stricture patients. The obstruction level was above the orifice of the cystic duct. The group included 19 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma and two patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Twelve patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma received two stents (in T or Y configuration) for drainage of bilateral hepatic ducts.

Group II (40 patients) was consisted of distal stricture patients. The obstruction level was at or below the orifice of the cystic duct. The group included 9 patients with cholangiocarcinoma, 17 patients with pancreatic cancers, 3 patients with ampulla of Vater cancers, 2 patients with gall bladder cancers, and 9 patients with lymph node metastases of colon cancer (2/9), gastric cancer (3/9), lung cancer (1/9), nasopharyngeal cancer (1/9), hepatocellular cancer (1/9) and laryngeal cancer (1/9).

Eight patients in group I (8/21) and 24 patients (24/40) in group II died at the time of evaluation. Covered EMS were inserted in seven patients with distal stricture and the other 53 patients received uncovered stents.

If stent stenosis was noted during follow-up, either a second EMS (six patients), or a plastic stent through an original EMS (three patients) or PTCD (one patient) or nasobiliary drainage (three patients) was set up. However, some patients chose conservative treatment after stent occlusion.

Stent patency and survival

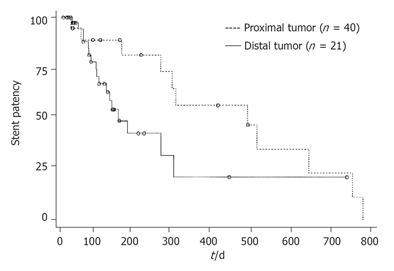

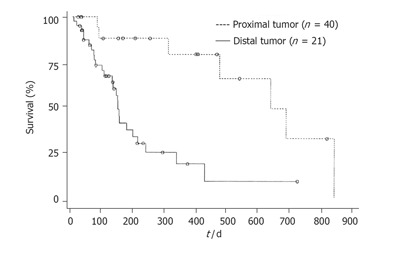

The mean time of stent patency was 421 ± 67 d in group I and 168 ± 18 d in group II. The difference was significant in borderline between the two groups (P = 0.0567). The mean survival time was 574 ± 76 d in group I and 182 ± 25 d in group II. There was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.0005). Cumulative stent patency and patient survival according to the Kaplan-Meier life table are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing cumulative stent patency. The difference was borderline significant between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing survival of the patients. There was a significant difference observed between the proximal tumor and distal tumor.

Early complications

Early complications were defined as "complications occurring within 30 d after EMS placement". Nine cases had early complications. Seven of them belonged to distal stricture and two belonged to proximal stricture. The clinical features of early complications are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Early complications after insertion of metallic stents

| Case | Complications | Type of stent | Timing of complication | Management | Result |

| 1 | Acute pancreatitis | Covered stent | Immediately | Conservative | Recovered |

| 2 | Acute pancreatitis | Covered stent | Immediately | Conservative | Recovered |

| 3 | Acute pancreatitis with pseudocyst | Uncoverd stent | Immediately | Percutaneous catheter drainage | Recovered |

| 4 | Inadequate expansion of stent | Uncoverd stent | 3 d | Balloon dilatation | Good |

| 5 | Inadequate expansion of stent | Uncoverd stent | 3 d | Balloon dilatation | Good |

| 6 | Acute cholangitis without Stent stenosis | Uncoverd stent | 22 d | Antibiotics | Recovered |

| 7 | Peritonitis | Uncoverd stent | 30 d | Antibiotics | Recovered |

| 8 | Stent occlusion | Uncoverd stent | 22 d | PTCD | Good |

| 9 | Subcapsular liver abscess | Uncoverd stent | 1 d | Percutaneous catheter drainage | Recovered |

Case 1-7: distal stricture. Case 8-9: proximal stricture.

Late complications

Late complications were defined as "complications occurring after 30 d of EMS placement". A patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma suffered from common bile duct stones 175 d after stent placement. Endoscopic sphinterotomy was performed and the stones were extracted. Gallbladder empyema was in two patients. One of them received covered EMS due to cholangiocarcinoma near the orifice of the cystic duct and symptoms occurred 66 d after stent placement. The other patient received uncovered EMS due to hilar cholangiocarcinoma and symptoms occurred 37 d after stent placement. Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) relieved their symptoms. Three patients with pancreatic cancers suffered from gastric outlet obstruction (on days 80, 93 and 270 respectively) due to tumor invasion into the duodenum. Bypass surgery relieved their outlet obstructions.

Complications of covered EMS

It seemed that more complications occurred in patients who received covered EMS. However, we could not arrive at any final conclusion due to the limited number of cases in our series. Acute pancreatitis occurred immediately after stent placement in two cases (2/8). Fortunately, they recovered uneventfully after conservative treatment. Stent migration (1/8) was found in a patient with an ampulla of Vater tumor 85 d after stent placement. He received conservative treatment only because of tumor infiltration in the entire second portion of the duodenum and the patient expired soon after. One patient developed gallbladder empyema (1/8) 66 d after stent placement.Her symptoms were relieved after PTGBD.

DISCUSSION

Endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic stentplacement in the biliary tree has become a main stream in the treatment of inoperable malignant obstructive jaundice[1]. The major drawback of plastic stents is early stent clogging and migration in spite of various modifications in the design[2,3]. The use of EMS apparently improves the weak points of plastic stents. Although EMS is much more expensive than plastic stents, it is a cost-effective strategy [3,8]. EMS improves patient compliance due to prolonged stent patency and less complications[3].

According to Lee et al[6], patients with hilar obstruction have better clinical efficacy than those with common bile duct obstruction. In our study, we demonstrated similar results. Stent patency and patient survival were better in our patients with proximal stricture than in those with distal stricture. Twelve of 21 patients with proximal stricture received bilateral biliary drainage in our series. If one of the two stents were occluded, jaundice would rarely develop. However, stent occlusion would cause immediate jaundice in distal strictures.

Our study demonstrated that most of early complications were related to the effect of stents or manipulation procedures. Acute pancreatitis(3/9) might be due to occlusion of the pancreatic duct by covered stents or secondary to the ERCP procedure. Liver abscess (1/9) might be due to the contamination of the procedure. The inadequate expansion of EMS (2/9) might be due to poor function of the metallic wires.

Most late complications were related to tumor progression. The first case with gallbladder empyema in our study might be due to the dual effects of covered stents and tumor progression. The second case with gallbladder empyema might be due to tumor progression with cystic duct occlusion. The gastric outlet obstruction in patients with pancreatic cancers was, surely due to tumor extension. Almost all stenoses of the stent and/or cholangitis are caused by tumor growth with occluded ducts, but cholangitis unrelated to stent occlusion can be noted [11].

Although the patency of EMS is longer, there are many drawbacks after their placement, such as tumor ingrowth or overgrowth, mucosa hyperplasia induced by chronic inflammatory reaction to the stent meshes, biliary sludge and food impaction in transpapillary stents[9].Covered stents are significantly superior to uncovered stents by preventing tumor ingrowth[1,4,5]. However covered stents are risky for occlusion of branch ducts (such as side branches of bile ducts, cystic ducts or pancreatic ducts), stent migration and sludge formation. Only eight of our patients with distal stricture received covered stents, and complications occurred in four of eight. Complications included acute pancreatitis (2/8), gallbladder empyema (1/8) and stent migration (1/8). A higher rate of migration is another possible disadvantage of covered stents[10]. Due to the limited number of covered stents in our series, further studies are needed to determine the frequency of side effects in covered stents.

Because of the high cost of EMS, selection of patients and types of stents are important. Life expectancy shorter than 6 mo[8] or tumors with liver metastases[12] are not cost-effective for EMS placement. Although many types of EMS are now available, which type can best improve the cost-effectiveness and quality of life remains unknown[13-16].

In conclusion, EMS implantation is a feasible, palliative method for unresectable malignant biliary obstruction. The clinical efficacy of EMS in patients with proximal hilar tumors is superior to that in patients with distal tumors. Covered EMS is risky in regard to the complications due to pancreatitis although stent patency may be longer.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Li HY

References

- 1.Isayama H, Komatsu Y, Tsujino T, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Toda N, Nakai Y, Yamamoto N, Tada M, Yoshida H, et al. A prospective randomised study of "covered" versus "uncovered" diamond stents for the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction. Gut. 2004;53:729–734. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai CC, Mo LR, Lin RC, Kuo JY, Chang KK, Yeh YH, Yang SC, Yueh SK, Tsai HM, Yu CY. Self-expandable metallic stents in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996;95:298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmassmann A, von Gunten E, Knuchel J, Scheurer U, Fehr HF, Halter F. Wallstents versus plastic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: effects of stent patency of the first and second stent on patient compliance and survival. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:654–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thurnher SA, Lammer J, Thurnher MM, Winkelbauer F, Graf O, Wildling R. Covered self-expanding transhepatic biliary stents: clinical pilot study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:10–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02560140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezzi M, Zolovkins A, Cantisani V, Salvatori FM, Rossi M, Fanelli F, Rossi P. New ePTFE/FEP-covered stent in the palliative treatment of malignant biliary obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:581–589. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61651-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee BH, Choe DH, Lee JH, Kim KH, Chin SY. Metallic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: prospective long-term clinical results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:741–745. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieber A, Brambs HJ. Metallic stents in malignant biliary obstruction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;20:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s002709900107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arguedas MR, Heudebert GH, Stinnett AA, Wilcox CM. Biliary stents in malignant obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:898–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzidakis AA, Tsetis D, Chrysou E, Sanidas E, Petrakis J, Gourtsoyiannis NC. Nitinol stents for palliative treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice: should we stent the sphincter of Oddi in every case. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24:245–248. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-0030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HS, Lee DK, Kim HG, Park JJ, Park SH, Kim JH, Yoo BM, Roe IH, Moon YS, Myung SJ. Features of malignant biliary obstruction affecting the patency of metallic stents: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:359–365. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng JL, Bruno MJ, Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic palliation of patients with biliary obstruction caused by nonresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: efficacy of self-expandable metallic Wallstents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:33–39. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaassis M, Boyer J, Dumas R, Ponchon T, Coumaros D, Delcenserie R, Canard JM, Fritsch J, Rey JF, Burtin P. Plastic or metal stents for malignant stricture of the common bile duct Results of a randomized prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:178–182. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosca S. Choosing the metal biliary stent type for palliation of neoplastic stenosis during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2003;35:629–630. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad J, Siqueira E, Martin J, Slivka A. Effectiveness of the Ultraflex Diamond stent for the palliation of malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2002;34:793–796. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferro C, Perona F, Ambrogi C, Barile A, Cianni R. Malignant biliary obstruction treated by Wallstents and Strecker tantalum stents: a retrospective review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02807351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BH, Do YS, Lee JH, Kim KH, Chin SY. New self-expandable spiral metallic stent: preliminary clinical evaluation in malignant biliary obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:635–640. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]