Abstract

Problem

International medical electives typically represent a unidirectional flow of students from economically advantaged countries in the global “North” to resource-poor nations in the global “South.” Little is known about the impact of bilateral exchanges on students from less affluent nations.

Approach

Since 2007, students from the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) and medical schools in Ghana have engaged in a bilateral clinical exchange program. A 45-item online survey was distributed to all 73 Ghanaian medical students who had rotated at UMMS from 2008 to 2010 to assess perspectives on the value and impact of their participation.

Outcomes

Incoming Ghanaian students outnumbered outgoing UMMS students 73 to 33 during the study period. Of eligible Ghanaian students, 70% (51/73) participated in the survey, with 40 of 51 providing valid data on at least 50% of questions. Ninety-seven percent (37/38) reported that the UMMS rotation was valuable to their medical training, 90% (35/39) reported changes in how they approach patient care, and 77% (24/31) reported feeling better equipped to serve patients in their home community. Eighty-five percent of students (28/33) felt more inclined to pursue training opportunities outside of their home country after their rotation at UMMS.

Next Steps

More studies are needed to determine the feasibility of bidirectional exchanges as well as the short-term and long-term impact of rotations on students from under-resourced settings and their hosts in more resource-rich environments.

Problem

International health experiences have become an important component of medical school curricula for many students across the world. However, most international electives involve students from the “North” (including the resource-rich nations within Europe and North America) traveling to resource-poor areas (the global “South”) in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.1,2

Opportunities for international students to participate in US-based electives are limited,3 and while the proportion and type of opportunities that are allocated to international students from the South is unknown, a disparity clearly exists.1 This disparity has raised ethical concerns prompting a call for academic health centers in more affluent countries to initiate collaborative partnerships with medical schools in less affluent international settings.2 There is a paucity of literature regarding the design and structure of international rotations for students from the South. Furthermore, little is known about the impact of such experiences on these students, as most studies have focused on the perspectives of students from economically advantaged nations traveling to under-resourced international settings.

In response to these problems, the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) has, since 2007, sponsored a bilateral exchange program between UMMS students and medical students from universities in Ghana. This program was established for several reasons. First was a desire to respond collaboratively to a request from colleagues in Ghana who desired placements in U.S. institutions but were having difficulty finding schools that would host their students. Second, there was a desire to increase the access of UMMS students and residents to learning opportunities in Ghana and to do so in a balanced approach that would bring value to the learners in Ghana. The structure by which students from Ghanaian medical schools are hosted at UMMS is described here, as are results from an attitudinal survey assessing the value and impact that Ghanaian students attribute to participation in a US-based elective.

Approach

The Ghana–Michigan medical student exchange

In 1989, UMMS’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology partnered with the University of Ghana Medical School (UGMS) in Accra, Ghana, and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology School of Medical Sciences (KNUSTSMS) in Kumasi, Ghana. Bilateral exchanges between residents from UMMS and these two institutions were developed to strengthen the obstetrics training program in Ghana.4

In 2007, the program began accepting senior medical students. Ghanaian students typically spend three to four weeks in Ann Arbor, Michigan, participating in direct patient care and observing clinical activities through rotations that are similar to those experienced by UMMS third- and fourth-year students. Students also receive an orientation to the clinical environment with topics such as use of the electronic medical record and medical databases, proper sterile technique, searching the medical literature, and learning in the UMMS Simulation Center. A list of core competencies and learning objectives are provided to students at the beginning of their rotation.5

Students are assigned to specific clinical rotations depending upon availability and the interests of the student. Students predominantly rotate in obstetrics and gynecology or emergency medicine. Typically, six Ghanaian students rotate at UMMS during the three- to four-week period. In accordance with a bilateral memoranda of understanding between UMMS and the Ghanaian partner schools, neither Ghanaian students nor Michigan students are charged tuition when rotating at one of the partner institutions. Through the generosity of one of UMMS’s department chairs, Ghanaian students receive a $300 stipend to help offset per diem costs. Lodging and airport transit are arranged by UMMS. Students are responsible for financing airfare, visas, health insurance, transportation in Ann Arbor, and all incidentals (average cost: $3,000 per student). Most students require financial assistance, typically provided by their family and occasionally provided by small grants from companies or organizations in Ghana.

Ghanaian students who have completed at least some clinical rotations at their home institutions are eligible to participate in a UMMS rotation. These students are typically in their first or second clinical year (fourth and fifth years, respectively, of a six-year medical school curriculum). Prior to 2010, students were accepted by UMMS for participation on a first-come, first-served basis. In 2010, a more rigorous selection process was instituted. Clinical students are now recommended for participation by deans or department chairs at their home institutions on the basis of class rank and personal merit.

Assessing the value and impact of a UMMS rotation on Ghanaian medical students

We e-mailed all 73 Ghanaian medical students from UGMS and KNUSTSMS who had participated in rotations at UMMS between January 2008 and December 2010, asking them to complete a survey. All participants gave their electronic consent prior to participation. This study was reviewed and performed under an exemption granted by both the Ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the University of Ghana Medical School, which provided blanket exemption for all universities in Ghana, as well as the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Participants completed a 45-item online survey supported by SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, California). We developed the survey (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1) specifically for this study, based upon a combination of literature review, exploratory interviews, and expert review, followed by an iterative review and revision process. The survey included a demographic section that collected background information, including region of residence, level of training, other international experiences, and intended career path. An attitudinal section used a five-point Likert scale to assess students’ perceptions of the value and impact of participation in a UMMS-based rotation. Students were also given the opportunity to provide open-ended, narrative feedback at the end of the survey.

Participants were offered $5 in phone credits as a token of appreciation for their participation. After completing the survey, participants were directed to an independent web page to claim their phone credits, thus retaining anonymity.

Data analysis

We retrieved data from SurveyMonkey and exported them into SPSS v.19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) for analysis. Frequencies and basic descriptive statistics were calculated for each key variable. Demographic characteristics were selected to stratify the analysis and examine differences based on factors such as gender, age, or rotation (e.g. obstetrics and gynecology versus emergency medicine). Analyses were conducted using cross tabs and Pearson’s chi square.

Outcomes

Between January 2008 and December 2010, 73 Ghanaian medical students participated in a clinical elective at UMMS. During this same time, 33 UMMS students traveled to medical schools in Ghana for similar rotations.

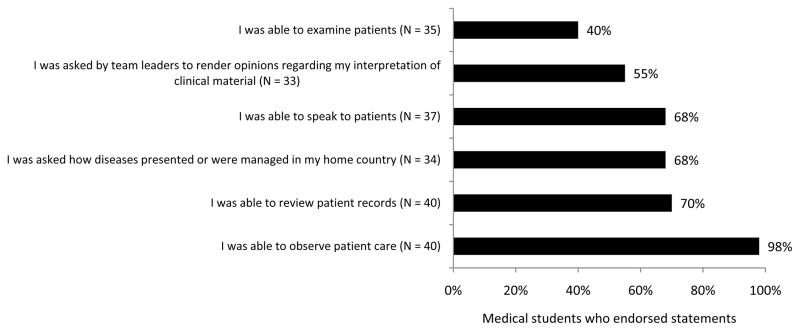

Of these 73 Ghanaian medical students, 51 (70%) agreed to take part in our study. Demographic data for the study participants are summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 illustrates the types of clinical experiences and interactions students had during their UMMS rotations.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Responding 51a (of 73) Ghanaian Medical Students who Participated in a University of Michigan Medical School Rotation Between January 2008 and December 2010

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at the time of rotationb (N = 50) | |

| 24–25 years old | 36 (72) |

|

| |

| Gender (N = 47) | |

| Male | 24 (51) |

|

| |

| Female | 23 (49) |

|

| |

| Geographic background | |

| Grew up in urban setting (N = 42) | 36 (86) |

|

| |

| Currently work/study in Greater Accra (N = 48) | 38 (79) |

|

| |

| Duration of rotation (N = 27) | |

| Six weeks | 1 (4) |

|

| |

| Four weeks | 16 (59) |

|

| |

| Three weeks | 10 (37) |

|

| |

| Assigned rotation (N = 51) | |

| Obstetrics & gynecology | 40 (78) |

|

| |

| Emergency medicine | 7 (14) |

|

| |

| Other | 4 (8) |

|

| |

| Level of training prior to UMMS rotationc (N = 49) | |

| Second clinical year | 45 (92) |

|

| |

| First clinical year | 4 (8) |

|

| |

| First international elective for the student (N = 50) | 39 (78) |

|

| |

| Students planning subsequent international electives (N = 50) | 6 (12) |

Abbreviations: UMMS = University of Michigan Medical School.

N per item ranged from 27 to 54, mode of 50.

Mean (SD): 24.7 (± 1.08) years.

Undergraduate medical training in Ghana typically consists of a six-year curriculum comprised of three preclinical and three clinical years.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Ghanaian medical students who responded “agree” or “somewhat agree” to statements pertaining to their clinical experiences during University of Michigan Medical School rotations held between January 2008 and December 2010. The number (N) of students who responded to each statement varied.

Perceived benefits of the UMMS rotation

Survey results suggest that Ghanaian medical students derive significant benefits from participation in a U.S.-based clinical elective. Notably, 37 of 38 respondents (97%) felt that the UMMS rotation was a valuable part of their medical training with 30 of 36 (83%) reporting that the learning objectives were clear. Students reported (1) improved medical knowledge (37/40; 93%), (2) greater appreciation for evidence-based medicine (34/36; 94%), (3) increased comfort searching medical literature (39/40; 98%), and (4) improved knowledge of U.S. medical care (38/39; 97%). Twenty-five of 32 students (78%) reported improvement in interpreting clinical information.

Many Ghanaian students experienced shifts in attitudes and perspectives as a result of their rotation. Thirty-seven of 38 respondents (97%) said that participation in the UMMS rotation led to personal growth and development. When asked about their perceptions of their future medical practice, the majority of participants (32/35; 91%) said that the UMMS experience changed the way that they were thinking about their career, and 35 of 39 (90%) cited a change in their approach to patient care. Twenty-four of 31 respondents (77%) felt better equipped to serve the people in their home community. Thirteen of 25 respondents (56%) felt more inclined to stay and work in their own community.

The benefits of participation in a U.S. elective were tempered by the fact that many students also reported having an increased desire to pursue training and career opportunities abroad as a result of their experience. Twenty-eight of 33 respondents (85%) felt more inclined to pursue training opportunities outside of their home country than they had been prior to the rotation, and 13 of 26 (50%) felt more interested in pursuing a career abroad than they did prior to their rotation. Statistically, there were no significant demographic differences between students reporting an increased interest in pursuing a career abroad than those who did not (data not shown). While it cannot be assumed that a statement of interest is an indicator of future migration, the possibility must be considered in light of the crisis in Africa’s health care human capacity.

Another weakness in the program appeared when students reported having less hands-on experience during their rotation than would be expected of a typical U.S. clinical student. Only 18 of 33 (55%) of the students were asked to render opinions on management, and only 14 of 35 (40%) were able to examine patients.

Limitations of this study include both its sample size and its overall response rate of 70%; missing data further decreased the sample size for each question and necessitated the reporting of item-specific Ns. Another limitation relates to the cross-sectional, self-reported nature of the study design; as such, direct conclusions cannot be drawn as to whether this experience in isolation led to specific learning outcomes for students. Finally, despite efforts to encourage candid responses, study participants may have felt compelled to inflate the value of their experiences due to fears of offending their hosts. However, given the anonymous, web-based nature of the data collection, this is unlikely to be a significant challenge to the validity of the findings presented here.

Next Steps

This is one of the first documented examples of a bilateral medical student exchange in which visiting students from Ghana outnumber outgoing UMMS students by more than two to one. This also constitutes one of the first attempts to assess the impact of international exchanges on students from the global South. There is a great need to document other existing bilateral exchange models in order to provide better insight into the feasibility of bilateral exchanges for academic institutions in the North seeking to build more reciprocity in their partnerships with Southern institutions.

Ghanaian medical students reported that participation in a U.S.-based elective can both be valuable and impact the development of skills and knowledge that shape future decisions regarding training and career choices. However, two areas of potential concern exist: first, the low rate of hands-on experience during their rotations, and second, their increased desire to partake in training and career opportunities abroad. Further research is warranted to explore in greater detail these and other issues identified in our study. As such, we have conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with a subset of study participants from the Ghana–UMMS exchange, the results of which are forthcoming.

One limitation of this exchange program is that participants must have the financial resources to travel to the U.S., meaning they likely represent a unique sampling of students from Africa. This group may be more attracted to pursuing careers abroad and more susceptible to the risks of “brain drain.” Regardless, creative approaches are warranted to ensure that bilateral exchanges are accessible to all medical students, not just the financially privileged.

Finally, little is known about the impact of the visiting students and trainees from the South on their Northern hosts, including the time required from faculty and other learners to accommodate these students into their programs. Further studies are needed to understand potential implications of reverse education and cultural exchange.

In summary, medical students from the global South benefit both personally and professionally by participating in rotations in the global North. The bilateral exchange program between UMMS and universities in Ghana can serve as a model for other medical schools interested in pursuing similar collaborations. However, these experiences must be thoughtfully designed to be equitable and to prevent future “brain drain.” Further studies are warranted to inform the design and implementation of balanced and equitable bilateral exchanges to support the educational needs of visiting trainees.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of the late Dr. Christine Ntim-Amponsah, Professor of Ophthalmology and former Dean at the University of Ghana Medical School, to the conceptualization and design of this study. The authors would also like to thank Jennifer Jones and Carrie Ashton for providing valuable insight into the background of the exchange program.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Training Grant R25 TW009345, funded by the Fogarty International Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the NIH Office of the Director Office of Research on Women’s Health and the Office of AIDS Research.

Footnotes

The authors have informed the journal that they agree that Drs. Abedini and Danso-Bamfo have completed the intellectual and other work associated with the first author.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at [[LWW INSERT LINK]].

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This study was reviewed and performed under an exemption granted by both the Ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the University of Ghana Medical School, which provided blanket exemption for all universities in Ghana, as well as the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Previous presentations: Initial findings from this study were presented at the 2011 Global Health Conference, Montreal, Canada, November 2011, as well as at the Sujal Parikh Memorial Symposium on Health and Social Justice/Physicians for Human Rights National Conference, March 2012, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Contributor Information

Dr. Nauzley C. Abedini, A member of the Class of 2014, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan and performed this work while a Fogarty Scholar.

Dr. Sandra Danso-Bamfo, Senior house officer, Ridge Hospital, Accra, Ghana.

Dr. Cheryl A. Moyer, Managing director, Global REACH, and assistant professor, Department of Medical Education, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Kwabena A. Danso, Professor of obstetrics and gynaecology and former dean, School of Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Ms. Heather Mäkiharju, Student programs coordinator, Global REACH, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Peter Donkor, Former pro-vice chancellor and professor of maxillofacial surgery, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology/College of Health Sciences, Kumasi, Ghana.

Dr. Timothy R.B. Johnson, Professor and chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Joseph C. Kolars, Professor of medicine and senior associate dean of education and global initiatives, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- 1.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolars JC, Cahill K, Donkor P, et al. Perspective: partnering for medical education in Sub-Saharan Africa: seeking the evidence for effective collaborations. Acad Med. 2012;87(2):216–220. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ede39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinley DW, Williams SR, Norcini JJ, Anderson MB. International exchange programs and U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2008;83(10 Suppl):S53–57. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183e351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinton Y, Anderson FW, Kwawukume EY. Factors related to retention of postgraduate trainees in obstetrics-gynecology at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1564–1570. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f09112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Accessed March 7, 2014];Core educational objectives: Ghana Medical Students at the University of Michigan. http://globalreach.med.umich.edu/sites/default/files/files/GHANA%20CORE%20EDUCATIONAL%20OBJECTIVES.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.