Abstract

Objective

Delays in HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) are common even among symptomatic individuals in Africa. We hypothesized that ART delays might be more common if traditional healers were the first practitioners consulted.

Design

Cross-sectional study

Methods

We interviewed 530 newly diagnosed HIV-infected adults (≥18 years of age) who were clinically symptomatic at the time of HIV testing in two rural districts in Zambézia Province, Mozambique. We ascertained their prior health care seeking behavior, duration of their symptoms, CD4+ cell counts at the time of entry into care, and treatment provided by traditional healer(s).

Results

Of 517 patients (97.5%) with complete histories, 62% sought care from a healer before presenting to the local health facility. The median time to first health facility visit from first relevant symptom was 2 months (interquartile range [IQR]:1–4.5) for persons who had not visited a healer, 3 months [IQR:2–6] for persons visiting one healer, and 9 months [IQR: 5–12] for persons visiting >1 healer (p<0.001). Healers diagnosed 56% of patients with a social or ancestral curse and treated 66% with subcutaneous herbal remedies. A non-significant trend towards lower CD4+ cells for persons who had seen multiple healers was noted.

Conclusion

Seeking initial care from healers was associated with delays in HIV testing among symptomatic HIV-seropositive persons. We had no CD4 evidence that sicker patients bypass traditional healers, a potential inferential bias. Engaging traditional healers in a therapeutic alliance may facilitate the earlier diagnosis of HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Mozambique, traditional healers, testing delays, health-seeking behavior, sub-Saharan Africa, task shifting

Introduction

People in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) often visit traditional healers before they seek care at an allopathic health facility.1–4 Unlike allopathic physicians, traditional and religious healers are thought by their clients to be able to diagnose ailments resulting from spiritual sources such as spirits, sorcery, and social transgressions. There are different types of healers: healers can specialize in different types of treatment, including herbal, spiritual, and/or religious based treatments.1,5–7 With the emergence of the HIV epidemic in Mozambique, the Ministry of Health (Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique [MISAU]) began encouraging patients to first seek care at a hospital; however, many Mozambicans continue to seek medical attention from healers before attending clinical services.4,8 In part, this is a consequence of cultural familiarity, availability, and inadequate allopathic health care.9 In Zambézia Province, there are an estimated 150 doctors and 850 nurses for >4 million persons (Figure 1), a number dwarfed by the estimated 25,500 healers in the province (unpublished data, Ministry of Health). While health care system limitations affect patient choices, many prefer visiting a healer regardless of the availability of clinical services.10

Figure 1.

An estimated 12.6% of Zambézians aged 15–49 years were infected with HIV as of 2009.11 HIV care and services are located in district hospitals and a few other large clinical sites, while rural areas provide counseling and testing services but refer patients to larger sites for care and treatment.12 Lower-cadre heath care providers, including medical technicians and nurses provide nearly all of HIV care in the region.8

For a person living with HIV, the long-term effects of delayed, interrupted or abandoned treatment are potentially severe, both due to higher rates of mortality and to the risk of transmission to sexual partners due to high viral load.13,14 Persons with a CD4+ cell count <200/µL are at far higher risk for opportunistic infections and malignancies; patients in programs that our group helps manage for MISAU had an initial median CD4 count of only 165 cells/µL (Interquartile range [IQR] 89–273) through the beginning of 2009. Earlier treatment (CD4 ≤550) has been linked to better health outcomes in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 trial and the World Health Organization (WHO) now recommends ART for persons with CD4 ≤500 for developing countries.15,16 Within antiretroviral therapy (ART)-based HIV programs, healers have been documented as hindering prompt and effective provision of HIV-related health services (including testing) 3,17,18 although this observation is not universal.19 Hence, earlier testing and successful linkage to ART-based care are vital to reducing morbidity and mortality in this rural region.

Few studies have attempted to quantify the time delay to testing associated with symptomatic, HIV positive individuals of unknown status who use traditional healers before seeking allopathic services and receiving HIV testing.17,19 In the present study, we sought to: 1) estimate the length of time that elapses between onset of illness/symptoms in an undiagnosed HIV+ person to HIV testing among patients seeking clinical care at participating health facilities; 2) determine the impact of choosing a healer for initial care on delay to testing on the patients’ CD+ cell count at time of testing; and 3) assess what diagnoses healers are providing for their patients and whether they referred them for further testing at the health facility.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of newly diagnosed (past three months) HIV positive adults (≥18 years) who were experiencing symptoms that caused them to seek allopathic health care services at the time of HIV testing. We interviewed 530 patients in two rural districts in southern Zambézia Province, Mozambique between December 2011 and August 2012. Patients were eligible to participate if they: (1) received an HIV test at one of the eligible clinical sites; (2) had tested HIV-positive in the past three months; (3) were 18 years of age or older; (4) were symptomatic before their HIV diagnosis; and (5) came to the hospital due to a physical complaint that led to referral for an HIV test. Of the 588 patients who were referred by nurses as being study eligible, 530 (90%) completed the interview. Interviews were conducted by study personnel who were not associated with the hospital staff. The interviews took 35–45 minutes and included questions about patient demographics, a retrospective structured interview to collect illnesses/conditions experienced continuously before HIV testing (all illnesses/conditions were recorded regardless of their connection with the eventual diagnosis of HIV and are hereinafter referred to as symptoms), length of time they had experienced this illness (we asked: “How long were you experiencing these symptoms before receiving an HIV test?”), and health seeking behavior related to these symptoms. The patients’ health identification number was also recorded in order to link with medical data, including CD4+ cell counts at first clinical visit and WHO status at treatment initiation. Patient CD4 counts were collected from medical charts through January 2013. All patients should receive a CD4+ cell count and WHO status at treatment initiation, but reagent stock outs and clinician oversights result in only a minority of patients obtaining their CD4+ cell counts. Visits to traditional healers were considered to have occurred for the purpose of the study at any time after initial symptoms began, and we also asked about the number of healers visited in that duration.

Ethical Approvals

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, the Comité Nacional de Bioética a Saúde in Mozambique, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Setting

Inhassunge and Namacurra districts are rural regions of Zambézia province with estimated populations of 110,000 and 240,000 respectively. Care and treatment are accessible at three centers in Inhassunge and seven centers in Namacurra (two via mobile clinics). Educational attainment in the region is typically less than primary school and few people have any monthly income.4,10,20 Median CD4+ cell counts at treatment initiation in our PEPFAR-supported program in Mozambique have risen by <10 cells/ µL over the past 4 years, despite substantial expansion of HIV testing.21

Study Size

We used data from a previously conducted cross-sectional study to estimate healer use in Zambézia4 (assuming 30% of patients had visited a traditional healer for their symptoms) and data from a study in West Africa to estimate variability (standard deviation=80 days) in delays to HIV testing among symptomatic HIV positive people 17 to inform sample size requirements. We aimed to enroll 410 HIV positive individuals, assuming a mean difference in delay time of 28 days, to be able to reject the null hypothesis that the mean delay time of healer-users and non-users are equal with probability (power) 0.9 and type I error of 0.05; the actual enrollment was 530 (i.e. 129% of the target sample size).

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics, including frequency/percentage (for categorical data) and median/IQR (for continuous data), are provided for sociodemographic data, survey responses, and clinical outcomes, stratified by use of traditional medicine. Patients who saw a traditional healer any time after initial symptoms began were asked whether they saw more than one healer and this data served as two primary outcomes: (1) visitation of a traditional healer and (2) number of healers consulted. Groups were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical data and rank sum tests for continuous data. Scatterplots for number of healers versus delay time or CD4 count were fit with Loess curves and Spearman’s correlation coefficients were estimated.22 Time from symptom to testing was modeled using multivariable linear regression with log-transformed delay time to testing as the outcome, including district, age, sex, education, travel time to clinic, transportation to clinic, consultation with religious leader and care from healer as covariates. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing values of covariates and to prevent case-wise deletion of missing data; 478 (92.4%) patients had complete data for all covariates. To relax linearity assumptions, we modeled age using a restricted cubic spline with three knots. 23 All hypothesis testing was two-sided with a level of significance set at 0.05. We employed R-software 2.15.1 (www.r-project.org) for all data analyses. Analysis scripts are available at http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ArchivedAnalyses

Results

Of the 530 participants who completed the study, 517 (97.5%) provided responses to the question “How long were you experiencing these symptoms before receiving an HIV test?” and were therefore included in the analysis (Table 1). Participants were 55% female, with a median age of 29 years (IQR: 23–37), median education of 4 years (IQR: 0–6), and living a median of 60 minutes from the hospital where they were being treated (IQR: 30–90). Only 19% of the participants spoke Portuguese in their homes (Echuabo is the local language of preference). Self-identified religious identity was 54% Catholic, 20% Muslim, 9% Seventh Day Adventist, 7% Baptist or Assembly of God, 5% other Christian, and 5% none.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 517 patients in HIV care services in rural Zambézia Province, Mozambique, comparing persons who did and did not seek initial care from a Traditional Healer

| No healer | 1 healer | 2 or more healers | Combined | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=196) | (n=115) | (n=206) | (n=517) | ||

| Female, n(%) | 91 (46%) | 76 (66%) | 118 (57%) | 285 (55%) | 0.003 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 28 (23–37) | 29 (21–38) | 29 (23–37) | 29 (23–37) | 0.67 |

| Name of Community , n(%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Inhassunge | 117 (60%) | 39 (34%) | 48 (23%) | 204 (39%) | |

| Namacurra | 79 (40%) | 76 (66%) | 158 (77%) | 313 (61%) | |

| Civil Status, n(%) | 0.11 | ||||

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Single | 37 (19%) | 19 (17%) | 21 (10%) | 77 (15%) | |

| Married | 117 (60%) | 64 (56%) | 123 (60%) | 304 (59%) | |

| Divorced | 19 (10%) | 19 (17%) | 36 (18%) | 74 (14%) | |

| Widowed | 23 (12%) | 13 (11%) | 25 (12%) | 61 (12%) | |

| Education (years), median (IQR) | 4 (1–6) | 3 (0–6) | 3 (0–6) | 4 (0–6) | 0.08 |

| Language spoken at home | |||||

| Portuguese | 35 (18%) | 21 (18%) | 41 (20%) | 97 (19%) | 0.86 |

| Chuabo | 186 (95%) | 109 (95%) | 196 (95%) | 491 (95%) | 0.99 |

| Other | 4 (2%) | 6 (5%) | 10 (5%) | 20 (4%) | 0.24 |

| Travel time to clinic (minutes), median (IQR) | 60 (40–90) | 60 (30–90) | 60 (30–90) | 60 (30–90) | 0.30 |

| Transportation source to clinic, n(%) | 0.04 | ||||

| Missing | 9 (5%) | 10 (9%) | 14 (7%) | 33 (6%) | |

| Walk | 135 (72%) | 69 (66%) | 115 (60%) | 319 (66%) | |

| Bike | 29 (16%) | 14 (13%) | 30 (16%) | 73 (15%) | |

| Car/motorcycle | 23 (12%) | 22 (21%) | 47 (24%) | 92 (19%) | |

| Duration of symptoms before testing (days), median (IQR) | 60 (21–150) | 90 (60–180) | 270 (150–365) | 120 (60–365) | <0.001 |

| HIV Knowledge (% correct), median (IQR) | 74 (63–82) | 70 (63–82) | 74 (67–82) | 74 (63–82) | 0.07 |

| Visited Religious Leader, n(%) | 17 (9%) | 13 (12%) | 34 (17%) | 64 (13%) | 0.05 |

| CD4+ cell count/µL, median (IQR) | 239 (83–385) | 352 (156–557) | 193 (68–382) | 242 (89–406) | 0.01 |

| Missing, n(%) | 126 (64%) | 73 (63%) | 117 (57%) | 316 (61%) | |

| WHO stage, n(%) | 0.24 | ||||

| Missing | 102 (52%) | 68 (59%) | 107 (52%) | 277 (54%) | |

| I | 50 (53%) | 24 (51%) | 36 (36%) | 110 (46%) | |

| II | 8 (9%) | 4 (9%) | 11 (11%) | 23 (10%) | |

| III | 33 (35%) | 19 (40%) | 47 (47%) | 99 (41%) | |

| IV | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) | 8 (3%) | |

| Height (cm), median (IQR) | 160 (155–167) | 160 (153–164) | 159 (154–166) | 160 (154–166) | 0.84 |

| Missing, n(%) | 93 (47%) | 66 (57%) | 106 (51%) | 265 (51%) | |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 48.0 (44.8–53.5) | 48.0 (41.9–54.0) | 46.8 (40–54.3) | 47.5 (41.5–54) | 0.23 |

| Missing, n(%) | 86 (44%) | 51 (44%) | 86 (42%) | 223 (43%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 19.5 (17.8–21.5) | 18.4 (17.0–21.4) | 18.2 (16.5–21.2) | 19.0 (17.0–21.4) | 0.26 |

| Missing, n(%) | 122 (62%) | 77 (67%) | 127 (62%) | 326 (63%) |

Percentages are computed using the number of patients with a non-missing value. Continuous variables are reported as median with interquartile range (i.e., the 25th and 75th percentiles).

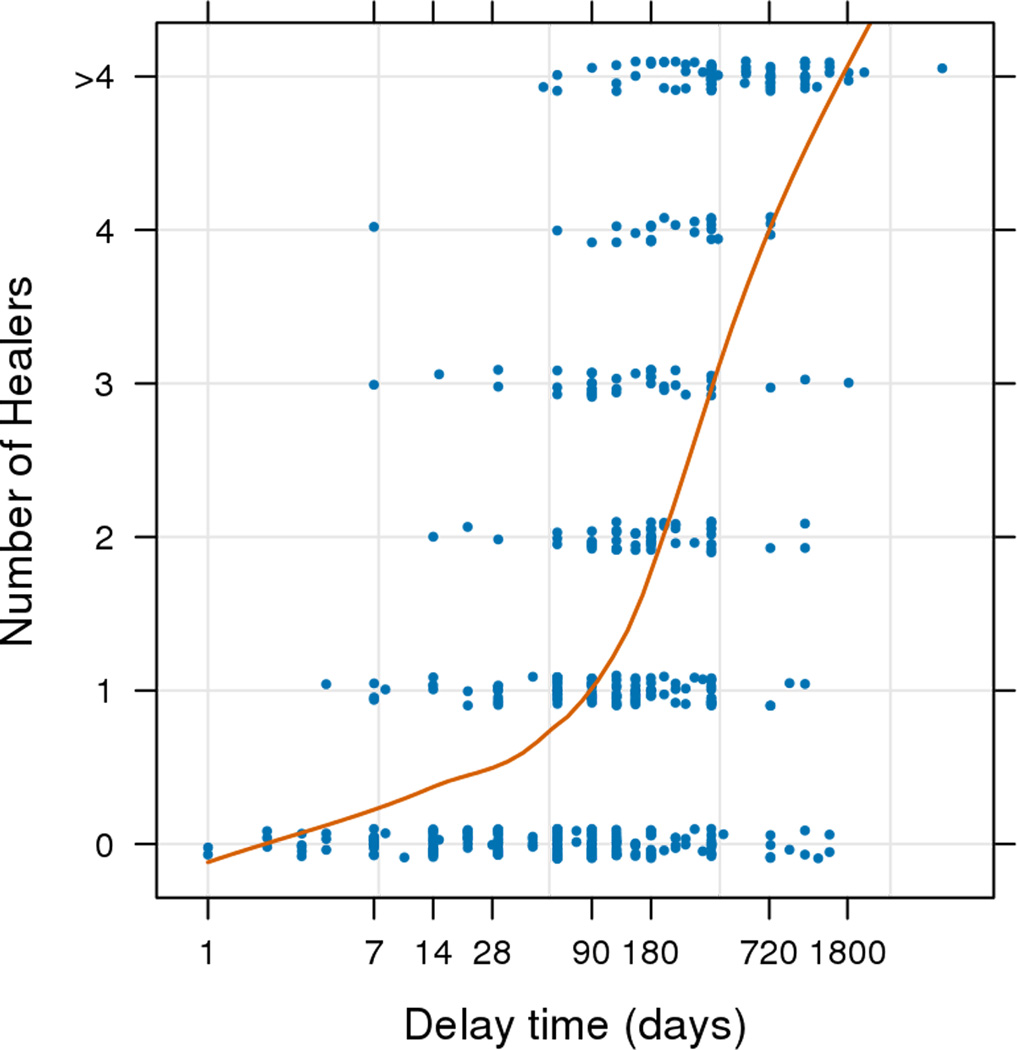

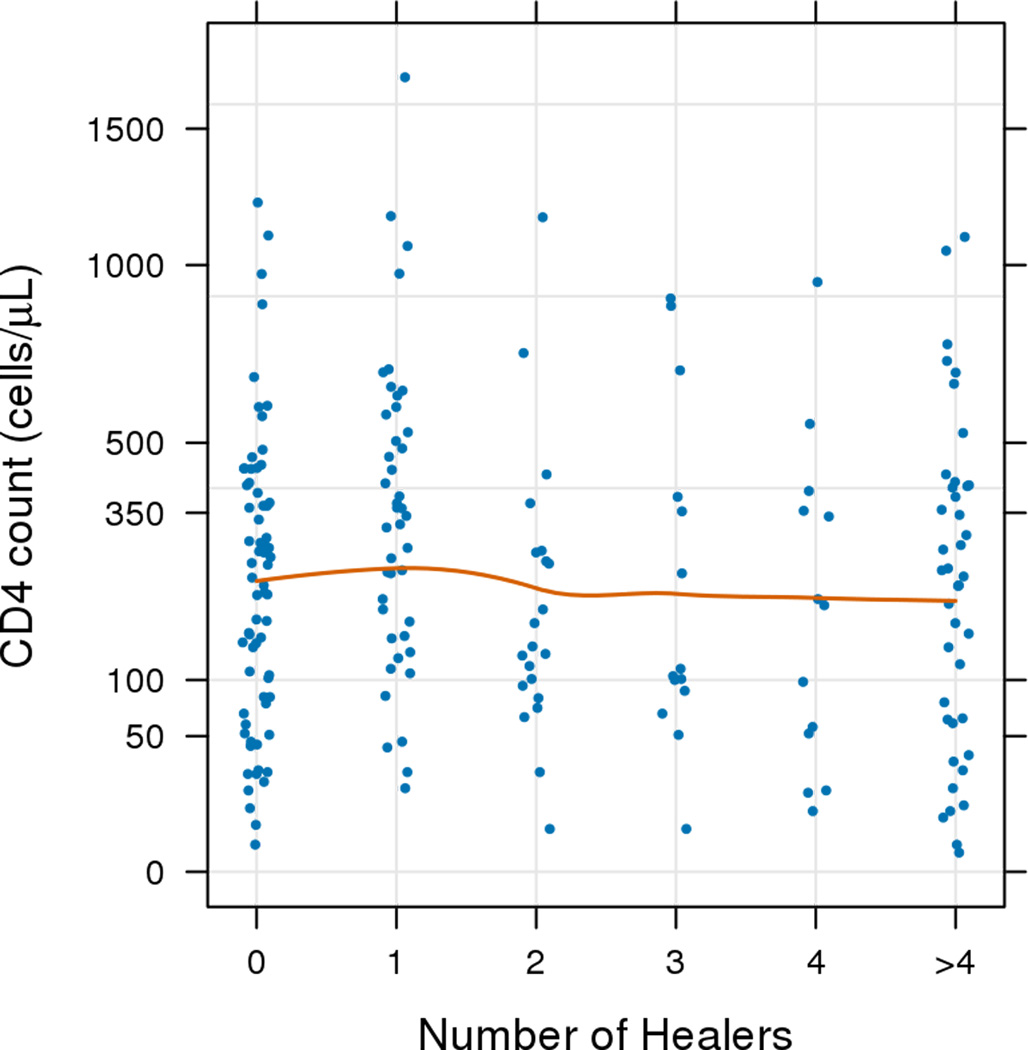

A majority of participants (n=321; 62%) first sought care from a healer before seeking care from the health facility. Compared to persons who did not first visit a healer, participants who first visited a healer for their symptoms were more likely to be female, had a median one year less of formal education (three vs. four years), were more likely to have to use a car/motorcycle to get to the clinic (vs. walking or bicycle), and were more likely to have also sought care from a religious leader. Median time to clinical visit from first symptom(s) was two months (IQR: 1–4.5) for those who did not visit a healer, three months (IQR: 2–6) for those who saw a single healer, and nine months (IQR: 5–12) among those who saw two or more healers (p=<0.001). A scatterplot with Loess curve of delay time by number of healers visited shows a trend of increasing delay times among those who consulted with increasing numbers of healers (Figure 2a) (Spearman ρ=0.54; p<0.001). A scatterplot with Loess curve of CD4 cell counts shows an insignificant decrease in CD4 by number of healers (Figure 2b) (Spearman ρ=−0.05; p=0.49).

Figure 2.

We conducted a linear regression model to determine factors associated with delayed time to clinical visit (Table 2). Covariates identified a priori included: sex, age, education, travel time to clinic, transportation, number of consultations with a healer before the clinic (0 to >4), consultation with a religious leader, and community (Inhassunge or Namacurra). Female patients had an average 30% longer delay to testing than males (p=0.02). A patient aged 20 years had 30% shorter delay to testing compared with a patient aged 30 (p=0.02). We failed to detect independent associations between education, travel time, consultation with religious leader and transportation with delay to testing. Patients in Namacurra had 2.0 times higher average delayed times to clinical visit than those at Inhassunge (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression: estimates for log(time delay to testing) for 517 patients in HIV care services in rural Zambézia Province, Mozambique, including persons who did and did not seek initial care from a Traditional Healer

| Estimatea (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 1.31 (1.05, 1.63) | 0.019 |

| Age | 0.018 | |

| 20 years | 0.70 (0.55, 0.90) | |

| 30 years (ref) | 1 | |

| 40 years | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | |

| 50 years | 0.90 (0.66, 1.21) | |

| Education (per 2 years) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) | 0.058 |

| Travel time to clinic (per 30 minutes) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 0.79 |

| Transportation | 0.66 | |

| Walk (ref) | 1 | |

| Bike | 1.14 (0.84, 1.54) | |

| Car/motorcycle | 1.09 (0.81, 1.45) | |

| Traditional healer (TH) use | <0.001 | |

| Did not consult TH (ref) | 1 | |

| Consulted 1 TH | 1.47 (1.12, 1.93) | |

| Consulted 2 TH | 2.45 (1.73, 3.47) | |

| Consulted 3 TH | 2.12 (1.42, 3.16) | |

| Consulted 4 TH | 2.90 (1.78, 4.73) | |

| Consulted 5 or more TH | 5.69 (4.16, 7.78) | |

| Consulted religious leaderb | 1.13 (0.83, 1.54) | 0.45 |

| Community | <0.001 | |

| Namacurra (ref) | 1 | |

| Inhassunge | 0.52 (0.40, 0.66) |

Because duration from symptom to testing is log-transformed, the model effect is the ratio of the geometric mean for the comparison and reference groups. Thus, we are able to summarize delay time in terms of percent change.

There is little evidence of a hypothesized interaction between use of traditional and/or religious healers (p=0.78); the interaction term was not included in this final model.

Prior consultation with a healer was associated with delayed time of diagnosis (p<0.001). Compared to someone who did not consult any healer, participants who visited a single healer had a 1.5 times longer delay, those who consulted with three healers had a 2.1 times longer delay, and those who consulted with five or more healers had a 5.7 times longer delay to testing. When running the same multivariable model dichotomizing any use of healers as the main exposure of interest, people who consulted a healer had a 2.4 times longer delay than those who did not [Effect estimate (95% CI): 2.42 (1.91, 3.05); data not shown]. From the model, we estimated mean delay time by healer use for our average participant: a woman, age 29, with four years of formal education, who walks to the clinic in one hour, lives in Namacurra and does not consult with a religious leader on health concerns; that patient had a mean delay of 99 days (95% CI: 74, 132 days) from first symptom to testing if she did not visit a healer (Table 3). Her delay time increased as she consulted with greater numbers of healers, such that this patient was delayed an average of 1.5 years (95% CI: 415, 767 days) from first symptom to testing if she sought care from 5 or more healers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predicted mean delay time by TH use (from model)

| Traditional healer use | Mean Delay (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| No healer | 99 days (74, 132) |

| 1 TH | 146 days (110, 193) |

| 2 TH | 243 days (171, 344) |

| 3 TH | 210 days (137, 321) |

| 4 TH | 287 days (175, 471) |

| >4 TH | 564 days (415, 767) |

Adjusted to: sex=Female age=29 education=4 distance to clinic=60 transportation to clinic=walk religious help=No community=Namacurra.

Patient symptoms were documented at time of enrollment (data not shown). Pulmonary symptoms (coughing, trouble breathing), gastrointestinal issues (diarrhea), fever, musculoskeletal problems (body aches) and neurological/psychological complaints (dizziness, headaches) were the most common symptoms reported. People who first visited a healer were more likely to report having pulmonary, musculoskeletal, systemic problems (including skin rashes), and genitourinary system/pregnancy-related symptoms than those who first sought care from a clinical site. Specifically, patients with cough (p=0.005), body aches (p=0.004), diarrhea (p=0.003), muscle weakness (p=0.04) and abdominal pains (p=0.006) were more likely to first seek care from a traditional healer. Self-reported delay time was longer among people who first saw a healer who experienced abdominal pain (157 days vs. 269 days; p<0.001), lack of appetite (122 days vs. 240 days, p=0.01), and those who experienced vaginal discharge (224 days vs. 426 days, p<0.02).

Of patients seen by just one healer, 159 of 323 (55%) were administered herbs, “injected” subcutaneously using razor blades and rubbing the herbs into the cuts. Of 188 persons seen by ≥2 healers, 66% reported having had the subcutaneous herbal inoculation. Although 12 training sessions had been conducted with traditional healers in these two communities by MISAU and partners to help healers identify the symptoms of HIV, only 30 (9%) of our participants reported being referred to the health facility by a healer. Three diagnoses were most commonly reported to have been made by healers: being cursed (182, 56%), of biological origin (49, 15%) and angering spirits (31, 10%). Of those 30 patients who reported healer referral to the health facilities for treatment, 90% reported this as their primary reason for their presentation at the health facility.

Discussion

We found significant differences in delayed time to testing among those who did and did not visit a healer before visiting a clinic for their symptoms. If we can effectively partner with healers to enable early referral in a given community, we may be able to facilitate earlier HIV testing, enabling needed earlier therapy.24 Patient referral from a traditional healer to clinical site is fairly straightforward: healers provided patients with a referral form indicating their symptoms; patients bring this form to the clinical site where they present it to the intake nurse and wait in line as would any other patient. Our previous studies revealed that patients who admitted to visiting a healer were often criticized by clinicians in Mozambique.25 New training and clinical practices are aiming to change this dynamic: to encourage patients to accept healer referral, the consultation fee (1 MT or US $0.03) has recently been waived for these patients and in some sites the patient is allowed to “jump the queue” and see the clinicians faster than patients who were not referred by a healer.

We saw a greater proportion of women seeking care from a healer. We can only hypothesize the reasons for this difference: (1) women have lower socioeconomic status and are required to complete a disproportionate amount of farming labor and housework in these communities which may limit their ability to travel to clinical sites for treatment4,20 and (2) women may prefer to seek care from a traditional healer for linguistic reasons: fewer women than men in these communities speak Portuguese, the language of preference at health facilities.20,25

The use of healers as primary care providers in rural Mozambique suggests the importance of engaging healers in HIV testing strategies.10 However the paltry 9% of patients referred for clinical treatment, despite prior training of 200 healers in these two districts is disappointing. The educational training that we have already done has not been effective to motivate referral of ill patients to health facilities for HIV testing. Recent examples of successful engagement of healers and allopathic providers may provide encouragement for moving forward with the goal of linking the two systems further.26–31 Healers need to have a clearly defined role in patient care that extends beyond referral, such as adherence counseling, and ideally would be compensated for worthwhile services, whether financially or otherwise. Once referred to the hospital, patients encounter an additional challenge: a 2012 study in Zambézia found that even when healers referred patients to the health facility, the proportion of patients tested for HIV at first visit was only 3%.32 Further investigation is needed to determine whether this suggests a lack of respect from allopathic providers for the opinions of healers or reflects a general failure to test symptomatic patients. Following an HIV positive diagnosis, the course of traditional treatments provided is not well understood33. Future research in this area is required to ensure that healer treatments do not encourage the co-administration of potentially hepato- and/or nephrotoxic agents or result in additional possible deleterious drug-herb interactions.34–38

Treatment strategies employed by healers to treat patient symptoms put themselves and their patients at risk of blood-borne pathogens.10 Healers who practice cutting and herbal rubbing on their patients increase direct exposure to infected blood by reusing razors and other implements such as sticks for rubbing the herbs into the skin. A paucity of rubber gloves and non-reusable sterile razors suggest that the risk of inter-patient and/or healer HIV/hepatitis transmission may be substantial.39

Study strengths include the large sample size and the high rate of participation, suggesting potential generalizability to this rural population. The collection of clinical data to compare with self-reported time delays allowed us to validate recall, but we were limited by the availability of CD4+ cell counts in only a subset of subjects. This percentage of missing CD4+ cell data (39%, Table 1) is the same as found among the HIV patient population in these rural Mozambican clinics (40%, data not shown). While we have no evidence of non-randomness of ascertainment, we cannot be sure that the CD4 counts are representative of the full population, a limitation in our study. Since CD4 counts were lower in persons who had seen more than one traditional healer, we do not believe that sicker persons were bypassing healers to go directly for care. As a retrospective cross-sectional study, patient recall of time since symptoms began can be incorrect. If there were systematic bias in the data by use of traditional medicine, our results will not accurately reflect true delays to clinical visits. We did not capture data on length of time patients had been experiencing symptoms before seeking care from a traditional healer of why they chose to visit a healer vs. a clinician, but this is an important area for future research. As our study was limited only to people who have received an HIV positive test result, we did not capture data about those who had HIV but refused to test or after testing did not present at the clinical site for test results. Persons who might have died of HIV before reaching the HIV clinics will not have presented to us for the healer assessment, an unseen cohort whose characteristics of advanced HIV disease and failure to present to the clinic might indicate our findings to be a minimum estimate of the true delays associated with healer visits.40 Also, as our data are only from two rural sites, the data may not be generalizable to urban areas of Mozambique or to other sub-Saharan African countries.

Our findings can alert clinical HIV service providers in Africa that initially seeking care from healers was frequent and was associated with delays in HIV testing, even among symptomatic HIV positive patients. We cannot be sure that this is causal, but even the association is of interest, given the low CD4+ cell counts seen all over Africa in persons presenting for HIV care.41,42 With the majority of our patients first seeking care from a healer when sick, working with healers to facilitate a quick diagnosis and referral to the clinic when appropriate would seem to be a priority in HIV programs in Africa. The 9% proportion of healer referrals to the health facilities was discouraging given prior HIV training that had been provided to healers in these districts. Since healers continue to neglect patient referral even after receipt of information about available services, education alone is likely not sufficient; a new model to incentivize referral behavior is needed. In addition, health care workers must be encouraged to welcome such referrals, not always a guaranteed reaction in the setting of hostility between healers and allopathic providers. Development and testing of a model that incentivizes healer referral of sick patients for HIV testing and care will be a high priority for new research, as will determining a productive long-term relationship for augmenting treatment adherence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants who participated in the study, the Mozambique Ministry of Health, and the clinicians at the two study clinics. The CDC provided funding for data collection. CMA is supported in part by Clinician and Translational Science Award (CTSA)/Vanderbilt Clinical &Translational Research Scholars (VCTRS) grant (2UL1TR000445). The CDC reviewed the protocol and provided suggestions on sample size. The CTSA/VCTRS had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. CMA had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest & Sources of Funding: No conflict of interest exists. The CDC provided funding for data collection.

References

- 1.Kale R. Traditional healers in South Africa: a parallel health care system. BMJ. 1995 May 6;310(6988):1182–1185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stekelenburg J, Jager BE, Kolk PR, Westen EH, van der Kwaak A, Wolffers IN. Health care seeking behaviour and utilisation of traditional healers in Kalabo, Zambia. Health Policy. 2005 Jan;71(1):67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banda Y, Chapman V, Goldenberg RL, et al. Use of traditional medicine among pregnant women in Lusaka, Zambia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007 Jan-Feb;13(1):123–127. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audet CM, Blevins M, Moon TD, Vergara AE, Vermund SH, Sidat M. Health Seeking Behavior in Zambezia Province, Mozambique. SAHARAJ. 2012;9(1):41–46. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2012.665257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green EC. Traditional healers and AIDS in Uganda. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medince. 1999;6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1089/acm.2000.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green EC, Zokwe B, Dupree JD. The experience of an AIDS prevention program focused on South African traditional healers. Soc Sci Med. 1995 Feb;40(4):503–515. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeiffer J. Commodity fetichismo, the Holy Spirit, and the turn to Pentecostal and African Independent Churches in Central Mozambique. Culture, medicine and psychiatry. 2005 Sep;29(3):255–283. doi: 10.1007/s11013-005-9168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audet CM, Burlison J, Moon TD, Sidat M, Vergara AE, Vermund SH. Sociocultural and epidemiological aspects of HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audet CM, Groh KE, Moon TD, Vermund SH, Sidat M. Poor quality health services and lack of program support leads to low uptake of HIV testing in rural Mozambique. Journal of African AIDS Research. 2012;4:327–335. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.754832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Audet CM, Blevins M, Moon TD, et al. HIV/AIDS-Related Attitudes and Practices Among Traditional Healers in Zambezia Province, Mozambique. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medince. 2012;18(12):1–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.INSIDA. [Accessed August 14, 2013];National Survey on Prevalence, Behavioral Risks and Information about HIV and AIDS (2009 INSIDA) 2009 (May 24, 2011). http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/15255898/801713730/name/INSIDA.

- 12.Moon T, Burlison J, Sidat M, et al. Lessons learned while implementing an HIV/AIDS care and treatment program in rural Mozambique. Retrovirology: Research and Treatment. 2010;(3):1–14. doi: 10.4137/RRT.S4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi BH, Stringer JS, Moodley D. Antiretroviral drug regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a review of scientific, program, and policy advances for sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013 Jun;10(2):124–133. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggaley RF, White RG, Hollingsworth TD, Boily MC. Heterosexual HIV-1 infectiousness and antiretroviral use: systematic review of prospective studies of discordant couples. Epidemiology. 2013 Jan;24(1):110–121. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276cad7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on THE USE OF ARV DRUGS FOR TREATING & PREVENTING HIV INFECTION. WHO Press. 2013:273. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 17.Okome-Nkoumou M, Okome-Miame F, Kendjo E, et al. Delay between first HIV-related symptoms and diagnosis of HIV infection in patients attending the internal medicine department of the Fondation Jeanne Ebori (FJE), Libreville, Gabon. HIV Clin Trials. 2005 Jan-Feb;6(1):38–42. doi: 10.1310/ULR3-VN8N-KKB5-05UV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth A, Martin M, Cairns J. South Africa's health. Traditional healers may cause dangerous delays. BMJ. 1995 Oct 7;311(7010):948. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7010.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz RH, Tsai AC, Maling S, et al. No Association Found Between Traditional Healer Use and Delayed Antiretroviral Initiation in Rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2012 Jan 13; doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0132-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vergara A, Blevins M, Vaz LM, et al. Baseline Survey Report: Phase I and II: Zambezia Wide. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt Universit; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon TD, Vaz LM, Parrish DD, et al. Predictors of adult mortality and loss-to-follow-up within two years of initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in rural Mozambique. Poster Presentation presented at XIX International AIDS Conference; July 22–27, 2012; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleveland WS, Grosse E, Shyu WM. Local Regression Models. In: Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, editors. Statistical Models in S. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies : with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 15;363(3):257–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groh K, Audet CM, Baptista A, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:650. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ssali A, Butler LM, Kabatesi D, et al. Traditional healers for HIV/AIDS prevention and family planning, Kiboga District, Uganda: evaluation of a program to improve practices. AIDS Behav. 2005 Dec;9(4):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green EC. The participation of Africa Traditional Healers in AIDS/STI prevention programmes. AIDSLink. 1995;(26):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makundi EA, Malebo HM, Mhame P, Kitua AY, Warsame M. Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: the case of Kilosa and Handeni Districts, Tanzania. Malaria journal. 2006;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mashamba T, Peltzer K, Maluleke TX, Sodi T. A controlled study of an HIV/AIDS/STI/TB intervention with faith healers in Vhembe District, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2011;8(5 Suppl):83–89. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbeh GN, Edwards R, Ngufor G, Assah F, Fezeu L, Mbanya JC. Traditional healers and diabetes: results from a pilot project to train traditional healers to provide health education and appropriate health care practices for diabetes patients in Cameroon. Global health promotion. 2010 Jun;17(2 Suppl):17–26. doi: 10.1177/1757975910363925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peltzer K, Mngqundaniso N, Petros G. A controlled study of an HIV/AIDS/STI/TB intervention with traditional healers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2006 Nov;10(6):683–690. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Audet CM, Salato J, Blevins M, Amsalem D, Vermund SH, Gaspar F. Educational Intervention Increased Referrals to Allopathic Care by Traditional Healers in Three High HIV-Prevalence Rural Districts in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peltzer K, Friend-du Preez N, Ramlagan S, Fomundam H, Anderson J. Traditional complementary and alternative medicine and antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(2):125–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills E, Cooper C, Seely D, Kanfer I. African herbal medicines in the treatment of HIV: Hypoxis and Sutherlandia. An overview of evidence and pharmacology. Nutrition journal. 2005;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babb DA, Pemba L, Seatlanyane P, Charalambous S, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Use of traditional medicine by HIV-infected individuals in South Africa in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Psychol Health Med. 2007 May;12(3):314–320. doi: 10.1080/13548500600621511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langlois-Klassen D, Kipp W, Jhangri GS, Rubaale T. Use of traditional herbal medicine by AIDS patients in Kabarole District, western Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Oct;77(4):757–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langlois-Klassen D, Kipp W, Rubaale T. Who's talking? Communication between health providers and HIV-infected adults related to herbal medicine for AIDS treatment in western Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2008 Jul;67(1):165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordier W, Steenkamp V. Drug interactions in African herbal remedies. Drug metabolism and drug interactions. 2011;26(2):53–63. doi: 10.1515/DMDI.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tjotta E, Hungnes O, Grinde B. Survival of HIV-1 activity after disinfection, temperature and pH changes, or drying. J Med Virol. 1991 Dec;35(4):223–227. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890350402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoover DR, Munoz A, Carey V, et al. The unseen sample in cohort studies: estimation of its size and effect. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Stat Med. 1991 Dec;10(12):1993–2003. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780101212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT, et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon TD, Burlison JR, Blevins M, et al. Enrolment and programmatic trends and predictors of antiretroviral therapy initiation from president's emergency plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)-supported public HIV care and treatment sites in rural Mozambique. Int J STD AIDS. 2011 Nov;22(11):621–627. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.010442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]