Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to meta-analyze published data about prevalence and malignancy risk of focal colorectal incidentalomas (FCIs) detected by Fluorine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT).

Methods

A comprehensive computer literature search of studies published through July 31st 2012 regarding FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT was performed. Pooled prevalence of patients with FCIs and risk of malignant or premalignant FCIs after colonoscopy or histopathology verification were calculated. Furthermore, separate calculations for geographic areas were performed. Finally, average standardized uptake values (SUV) in malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs were reported.

Results

Thirty-two studies comprising 89,061 patients evaluated by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT were included. The pooled prevalence of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT was 3.6% (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 2.6–4.7%). Overall, 1,044 FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT underwent colonoscopy or histopathology evaluation. Pooled risk of malignant or premalignant lesions was 68% (95% CI: 60–75%). Risk of malignant and premalignant FCIs in Asia-Oceania was lower compared to that of Europe and America. A significant overlap in average SUV was found between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs.

Conclusions

FCIs are observed in a not negligible number of patients who undergo 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT studies with a high risk of malignant or premalignant lesions. SUV is not reliable as a tool to differentiate between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs. Further investigation is warranted whenever FCIs are detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT.

Keywords: PET/CT, fluorodeoxyglucose, colonic uptake, incidentaloma, focal uptake, colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal incidentalomas (CIs) are defined as unexpected colorectal findings that are discovered on an imaging study unrelated to the large bowel. CIs represent a challenge for the clinicians: some of these findings are benign but the risk of malignancy in CIs might be significant.1

As Fluorine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT) are increasingly used, especially for oncologic patients, incidental uptake detected by these functional imaging methods are also increasing. 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT may sometimes reveal an unexpected area of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake within the large bowel in patients referred for other diseases and this finding is defined as CI.1,2

Both focal, segmental and diffuse unexpected 18F-FDG uptake in the large bowel were reported. Segmental and diffuse increased uptake of 18F-FDG in the large bowel are considered at low risk of malignancy, being more likely associated with inflammation, physiological uptake or radiopharmaceutical excretion. Conversely, unexpected focal 18F-FDG uptake in the large bowel is of greater concern since it may represent both benign, pre-malignant (i.e. colonic adenomas) or malignant lesions (i.e. primary colorectal cancer or metastatic lesions).1,2

Several articles have reported data about the prevalence and the malignancy risk of focal colorectal incidental uptake (FCIs) detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT with discordant results. A systematic review about this topic and a meta-analysis providing pooled estimates of prevalence and malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDGPET or PET/CT are still lacking. Therefore, the objective of our article is to meta-analyze published data about prevalence and malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT, in order to derive more robust estimates in this regard.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive computer literature search of the PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus databases was conducted to find relevant published articles on the prevalence and malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT. We used a search algorithm that was based on a combination of the terms: “incidental” AND “PET” OR “positron emission tomography” OR “fluorodeoxyglucose” OR “FDG”. No beginning date limit was used; the search was updated until July 31st, 2012. Only articles in English language were selected. To expand our search, references of the retrieved articles were also screened for additional studies.

Study selection

Original articles investigating both the prevalence and the malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were: a) articles not providing information about prevalence or malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT; b) articles not in English language; c) overlap in patient data (in this case the most complete article was included). Three researchers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. Articles were rejected if they were clearly ineligible. The same three researchers then independently reviewed the full-text version of the remaining articles to determine their eligibility for inclusion.

Data extraction

For each included study, information was collected concerning basic study data (authors, year of publication, country), instrumentation used (PET or PET/CT), number of patients evaluated with PET or PET/CT, number of FCIs detected by PET or PET/CT, number of FCIs verified by colonoscopy or histology, final diagnosis of FCIs, average standardized uptake values (SUV) in malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of patients with FCIs who underwent PET or PET/CT was obtained from individual studies using this formula: prevalence of FCIs = number of patients with FCIs / number of patients evaluated with PET or PET/CT ×100.

The risk of malignant or premalignant FCIs detected by PET or PET/CT was obtained from individual studies using this formula: risk of malignant or premalignant FCIs = number of malignant or premalignant lesions found between FCIs / number of FCIs revealed by PET or PET/CT and verified by colonoscopy or histology ×100.

Patients with a history of colorectal cancer were excluded from the analysis.

A random-effects model was used for statistical pooling of the data; pooled data were presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and displayed using forest plots. A I-square statistic was also performed to test for heterogeneity between studies. A sub-analysis of the risk of malignant and premalignant FCIs taking into account different geographic areas was carried out. Statistical analyses were performed using StatsDirect statistical software version 2.7.9 (StatsDirect Limited, UK).

Results

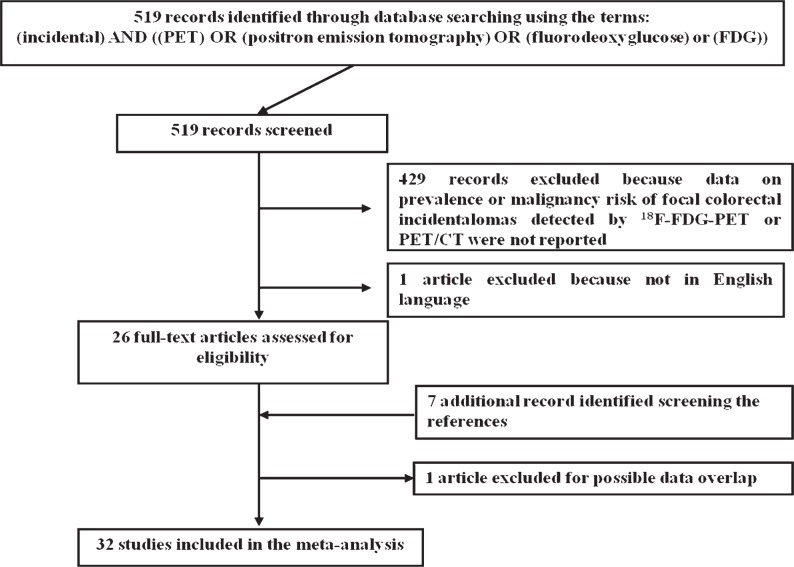

The comprehensive computer literature search from PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus databases revealed 519 articles. Reviewing titles and abstracts, 492 articles were excluded because they did not report any data on prevalence neither on malignancy risk of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT. One article was excluded because not in English language.3

Twenty-six articles were selected and retrieved in full-text version; seven additional studies were found screening the references of these articles. Out of these 33 articles potentially eligible for inclusion, after reviewing the full-text article, one article was excluded due to possible data overlap.4 Finally, 32 studies including 89,061 patients met all inclusion and exclusion criteria, and they were included in our meta-analysis (Figure 1) 2,5–35; 18 studies had data to calculate the pooled prevalence of FCIs and 31 studies had data to calculate the pooled risk of malignant of premalignant FCIs. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the search for eligible studies on the prevalence or malignancy risk of focal colorectal incidental uptake detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies about focal colorectal incidental uptake detected by 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT

| Authors | Year | Country | Device used | No. of patients evaluated | No. of patients with FCIs | No. of FCIs | No. of FCIs verified by colonoscopy or histology |

Final diagnosis of FCIs

|

Average SUV in FCIs

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant | Pre-malignant | Benign | No lesions identified | Malignant FCIS | Pre-malignant FCIs | Benign FCIs | ||||||||

| Zhuang H et al. | 2002 | USA/Brazil | PET | 197 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 8 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Tatlidil R et al. | 2002 | USA | PET | 3000 | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Chen YK et al. | 2003 | Taiwan | PET | 3210 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 6 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 5.74 ± 2.26* | 3.56 ± 0.68* | n.a. |

| Pandit-Taskar N et al. | 2004 | USA | PET | 1000 | n.a | n.a. | 10 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 13.6 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | n.a. |

| Agress H et al. | 2004 | USA | PET | 1750 | n.a. | n.a. | 27 | 3 | 18 | 3 | 3 | n.a | n.a | n.a. |

| Kamel EM et al. | 2004 | Switzerland | PET/CT | 3281 | n.a. | n.a. | 54 | 9 | 27 | 9 | 9 | n.a | n.a | n.a. |

| Lardinois D et al. | 2005 | Switzerland/Russia | PET/CT | 350 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | n.a. | n.a | n.a. |

| Ishimori T et al. | 2005 | USA | PET/CT | 1912 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Gutman F et al. | 2005 | France | PET/CT | 1716 | 45 | n.a. | 21 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 15 ± 11.6 | 12.0±3.7 | 25 |

| van Westreenen HL et al. | 2005 | The Netherlands | PET | 366 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Israel O et al. | 2005 | Israel | PET/CT | 4390 | n.a. | n.a. | 24 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 6 | n.a. | 14.0 ± 10.5 | n.a. |

| Even-Sapir E et al. | 2006 | Israel | PET/CT | 2360 | 33 | 39 | 29 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 4 | n.a | n.a | n.a. |

| Wang G et al. | 2007 | China/Australia | PET/CT | 1727 | n.a. | n.a. | 11 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Hemandas AK et al. | 2008 | UK | PET/CT | 110 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Terauchi T et al. | 2008 | Japan | PET | 2911 | n.a. | 111 | 111 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 84 | 8.31 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lee ST et al. | 2008 | Australia | PET/CT | 2916 | 85 | 95 | 45 | 12 | 24 | 2 | 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Tessonnier L et al. | 2008 | France | PET/CT | 4033 | n.a. | n.a. | 44 | 8 | 25 | 4 | 7 | 12.3 ± 5 | 9.8 ± 6.1 | 8.2±2.1 |

| Strobel K et al. | 2009 | Switzerland | PET/CT | 598 | n.a. | 14 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lee JC et al. | 2009 | Australia | PET/CT | 1665 | 62 | 70 | 35 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Weston BR et al. | 2010 | USA | PET/CT | 330 | 50 | 52 | 52 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 15 | 17.2* | 14.2 ± 7.2* | n.a. |

| Kei PL et al. | 2010 | USA/Singapore/Hong Kong | PET/CT | 2250 | n.a. | n.a. | 22 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 4 | n.a. | 20.7 ± 11.3* | 12.0* |

| Özkol V et al. | 2010 | Turkey | PET/CT | 2370 | n.a | n.a. | 16 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Luboldt W et al. | 2010 | Germany | PET/CT | 2338 | 50 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Peng J et al. | 2011 | China | PET/CT | 10978 | 148 | n.a. | 125 | 32 | 23 | 5 | 65 | 9.7* | 8.2* | 6.1* |

| Treglia G et al. | 2012 | Italy | PET/CT | 6000 | 64 | n.a. | 51 | 13 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 9.6 ± 4.7 | 8.5 ± 5.2 | 6.5 ± 3.6 |

| Farquharson AL et al. | 2012 | UK | PET/CT | 555 | 53 | n.a. | 26 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Salazar Andia G et al. | 2012 | Spain | PET/CT | 2220 | n.a. | n.a. | 55 | 13 | 27 | 10 | 5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Oh J-R et al. | 2012 | Republic of Korea | PET/CT | 21317 | n.a. | 296 | 102 | 32 | 43 | 13 | 14 | 13.6 ± 4.9* | 8.4 ± 4.5* | 6.8* |

| Lin M et al. | 2012 | Australia | PET/CT | 649 | n.a. | n.a. | 18 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 6.0 | 10.4 | 5.8 |

| Yildirim D et al. | 2012 | Turkey | PET/CT | 823 | 28 | 28 | 19 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 10 | n.a | n.a | n.a. |

| Gill RS et al. | 2012 | Canada | PET or PET/CT | 1500 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7.4 | n.a. | 4.1 |

| Shim JH et al. | 2012 | South Korea | PET/CT | 239 | 39 | 46 | 46 | 8 | 24 | 14 | 8.9 | 5.5 | n.a. | |

FCIs = focal colorectal incidental uptake; pts = patients; n.a. = not available;

significant statistical difference

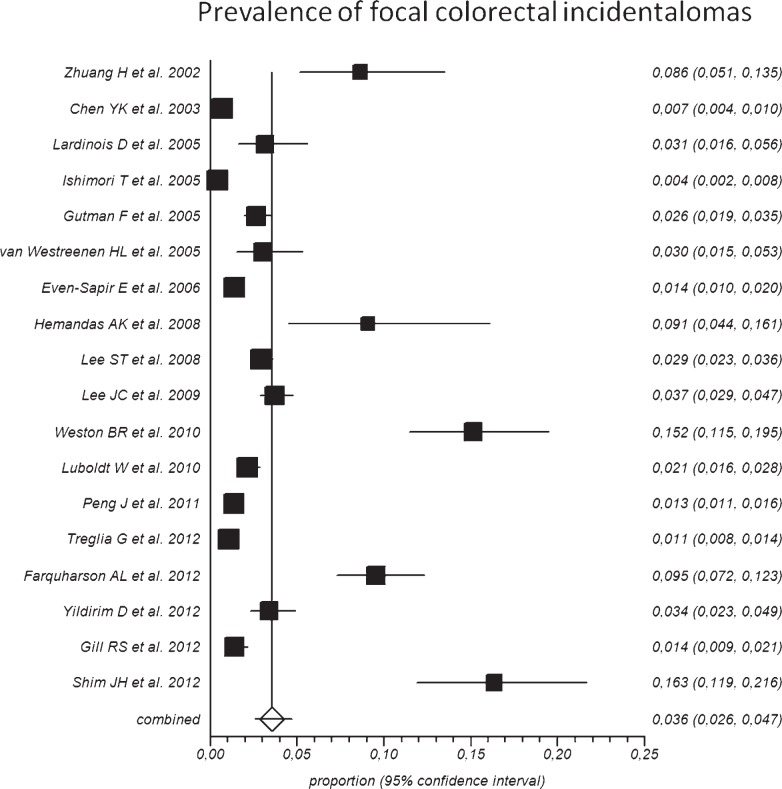

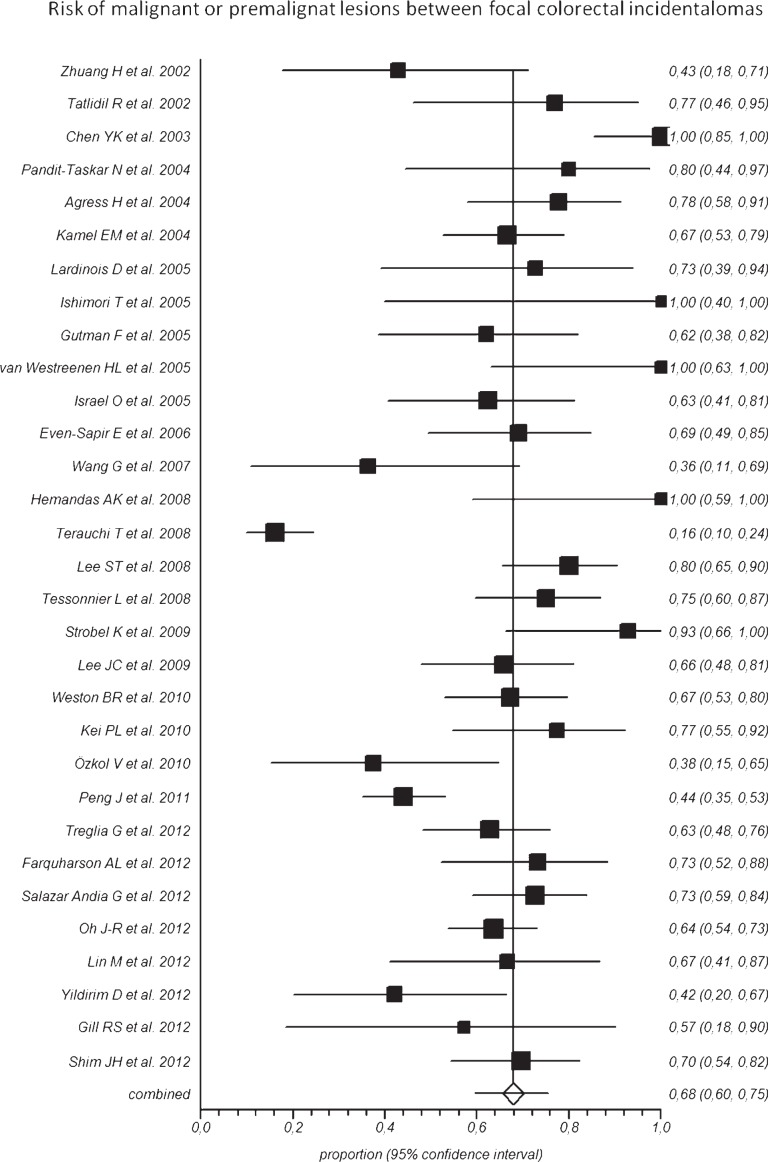

Overall, the pooled prevalence of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT in the included studies was 3.6% (95% CI: 2.6–4.7%), ranging from 0.4% to 16.3% (Figure 2). Overall, 1,044 FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT underwent colonoscopy or histology verification. Pooled risk of malignant or premalignant lesions between FCIs was 68% (95% CI: 60–75%), ranging from 16% to 100% in the included studies (Figure 3). The included studies were statistically heterogeneous (I-square: > 75%) both for prevalence and risk of malignant or pre-malignant FCIs.

FIGURE 2.

Plot of individual studies and pooled prevalence of patients with focal colorectal incidental uptake detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT, including 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Prevalence of patients with focal colorectal incidental uptake ranged from 0.4% to 16.3%, with pooled estimate of 3.6% (95%CI: 2.6–4.7%). The included studies were statistically heterogeneous (I-square: > 75%).

FIGURE 3.

Plot of individual studies and pooled risk of malignant or premalignant lesions between focal colorectal incidental uptake detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT, including 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The risk of malignant or premalignant lesions ranged from 16% to 100%, with pooled estimate of 68% (95%CI: 60–75%). The included studies were statistically heterogeneous (I-square: > 75%).

Concerning geographic distribution, the pooled risk of malignant or premalignant lesions in FCIs was lower in Asia-Oceania (62%; 95% CI: 43–79%) compared to America (70%; 95% CI: 61–79%) and Europe (70%; 95% CI: 65–74%).

A statistically significant difference in average SUV between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs was reported in some articles; nevertheless, a significant overlap about SUV was found between these three groups (Table 1).

Discussion

The increasing use of 18F-FDG-PET and PET/CT is associated with a concomitant increase in the number of patients with FCIs. The major difference between PET/CT and other imaging studies is that PET/CT provides both anatomic and metabolic information about incidental lesions found in the large bowel. The pattern of 18F-FDG uptake in the large bowel on PET imaging influences the likelihood of malignancy. Diffuse and segmental increased uptake detected at 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT in the large bowel are usually associated with benign conditions 1,2: such cases were not covered by this meta-analysis. We focused our analysis on FCIs because they can be associated with malignant or premalignant conditions in a significant number of cases.1,2

Several single-center studies have reported the prevalence of FCIs and risk of malignant and premalignant lesions between FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT with discordant findings.2,5–35 In order to derive more robust estimates and obtain evidence-based data about this topic, we performed a meta-analysis pooling published data.

Pooled results of our meta-analysis indicate that FCIs are observed in about 3.6% of patients performing 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT. Moreover, in our pooled analysis FCIs were associated with a high risk of malignant or premalignant lesions (68%), considering colonoscopy or histology confirmation as reference standard. Therefore, whenever a focal hot spot is detected within the large bowel, the 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT report should suggest further investigation, such as colonoscopy, in order to exclude a malignant or premalignant lesions.1,2

In the calculation of pooled malignancy risk, we considered premalignant lesions together with malignant lesions because colonic adenomas can transform from adenoma to carcinoma and progress insidiously in asymptomatic patients.

Performing a sub-analysis for geographic areas we found that the risk of malignant or premalignant lesions between FCIs was higher in America and Europe compared to Asia and Oceania. A possible explanation of this finding is that the prevalence of colorectal cancer is superior in these geographic areas.36

A significant difference in average SUV between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs was reported in some articles (Table 1). Nevertheless, a significant overlap about SUV was found between these three groups. Therefore, SUV alone should not be used to differentiate between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs. Indeed, it is well known that SUV is influenced by several factors, related to the patient as well as to technical aspects and procedures. Any calculation of a pooled SUV obtained by different studies - acquired with different tomographs, scan protocols, 18F-FDG injected activity, and patient characteristics - is in our opinion inappropriate, and therefore we decided not to meta-analyze data about SUV.

The present study has some limitations, related to the included articles, such as the selection bias in the calculation of malignancy risk and the heterogeneity between studies. Indeed, only a percentage of FCIs detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT underwent colonoscopy or histopathology confirmation in the included studies and this may represent a selection bias in the calculation of the risk of malignant or premalignant lesions. Furthermore, the included studies were statistically heterogeneous in their estimates of prevalence of FCIs and risk of malignant or premalignant lesions. This heterogeneity is likely to stem from diversity in methodological aspects between different studies. The baseline differences between the patients performing PET or PET/CT in the included studies may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity too. However, such variability was accounted for in a random-effects model.

Lastly, we did not perform a sub-analysis taking into account the device used (PET vs. PET/CT) or the site of FCIs (rectum and different colonic segments) because sufficient data in this regard could not be retrieved from the included studies.

Conclusions

FCIs are observed in a not negligible number of patients who undergo 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT studies with a high risk to be malignant or premalignant lesions. SUV is not reliable as a tool to differentiate between malignant, premalignant and benign FCIs. Further investigation, such as colonoscopy, is warranted whenever FCIs are detected by 18F-FDG-PET or PET/CT in order to exclude malignant or premalignant lesions.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Lin M, Koo JH, Abi-Hanna D. Management of patients following detection of unsuspected colon lesions by PET imaging. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1025–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treglia G, Calcagni ML, Rufini V, Leccisotti L, Meduri GM, Spitilli MG, et al. Clinical significance of incidental focal colorectal (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: our experience and a review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:174–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isobe K, Hata Y, Sakaguchi S, Takai Y, Shibuya K, Takagi K, et al. The role of positron emission tomography in the detection of incidental gastrointestinal tract lesions in patients examined for lung cancer. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;48:482–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra A, Ford A, De Noronha R, Matthews S. Incidental findings on positron emission tomography/CT scans performed in the investigation of lung cancer. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e229–37. doi: 10.1259/bjr/60606623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhuang H, Hickeson M, Chacko TK, Duarte PS, Nakhoda KZ, Feng Q, Alavi A. Incidental detection of colon cancer by FDG positron emission tomography in patients examined for pulmonary nodules. Clin Nucl Med. 2002;27:628–32. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatlidil R, Jadvar H, Bading JR, Conti PS. Incidental colonic fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: correlation with colonoscopic and histopathologic findings. Radiology. 2002;224:783–87. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YK, Kao CH, Liao AC, Shen YY, Su CT. Colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic adults: the role of FDG PET scan. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4357–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandit-Taskar N, Schöder H, Gonen M, Larson SM, Yeung HW. Clinical significance of unexplained abnormal focal FDG uptake in the abdomen during whole-body PET. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1143–47. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1831143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agress H, Jr, Cooper BZ. Detection of clinically unexpected malignant and premalignant tumors with whole-body FDG PET: histopathologic comparison. Radiology. 2004;230:417–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302021685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamel EM, Thumshirn M, Truninger K, Schiesser M, Fried M, Padberg B, et al. Significance of incidental 18F-FDG accumulations in the gastrointestinal tract in PET/CT: correlation with endoscopic and histopathologic results. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lardinois D, Weder W, Roudas M, von Schulthess GK, Tutic M, Moch H, et al. Etiology of solitary extrapulmonary positron emission tomography and computed tomography findings in patients with lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6846–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishimori T, Patel PV, Wahl RL. Detection of unexpected additional primary malignancies with PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:752–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutman F, Alberini JL, Wartski M, Vilain D, Le Stanc E, Sarandi F, et al. Incidental colonic focal lesions detected by FDG PET/CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:495–500. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Westreenen HL, Westerterp M, Jager PL, van Dullemen HM, Sloof GW, Comans EF, et al. Synchronous primary neoplasms detected on 18F-FDG PET in staging of patients with esophageal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1321–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israel O, Yefremov N, Bar-Shalom R, Kagana O, Frenkel A, Keidar Z, et al. PET/CT detection of unexpected gastrointestinal foci of 18F-FDG uptake: incidence, localization patterns, and clinical significance. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:758–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Gutman M, Lievshitz G, Zuriel L, Polliack A, et al. The presentation of malignant tumours and pre-malignant lesions incidentally found on PET-CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:541–52. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Lau EW, Shakher R, Rischin D, Ware RE, Hong E, et al. How do oncologists deal with incidental abnormalities on whole-body fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT? Cancer. 2007;109:117–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemandas AK, Robson NK, Hickish T, Talbot RW. Colorectal tubulovillous adenomas identified on fluoro-2-deoxy-D glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:386–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terauchi T, Murano T, Daisaki H, Kanou D, Shoda H, Kakinuma R, et al. Evaluation of whole-body cancer screening using 18F-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography: a preliminary report. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:379–85. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee ST, Tan T, Poon AM, Toh HB, Gill S, Berlangieri SU, et al. Role of low-dose, noncontrast computed tomography from integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography in evaluating incidental 2-deoxy-2-[F-18] fluoro-D-glucose-avid colon lesions. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tessonnier L, Gonfrier S, Carrier P, Valerio L, Mouroux J, Benisvy D, et al. Unexpected focal bowel 18-FDG uptake sites: should they be systematically investigated? Bull Cancer. 2008;95:1083–87. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2008.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strobel K, Haerle SK, Stoeckli SJ, Schrank M, Soyka JD, Veit-Haibach P, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) - detection of synchronous primaries with (18)F-FDG-PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:919–27. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JC, Hartnett GF, Hughes BG, Ravi Kumar AS. The segmental distribution and clinical significance of colorectal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake incidentally detected on PET-CT. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:333–37. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32832999fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weston BR, Iyer RB, Qiao W, Lee JH, Bresalier RS, Ross WA. Ability of integrated positron emission and computed tomography to detect significant colonic pathology: the experience of a tertiary cancer center. Cancer. 2010;116:1454–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kei PL, Vikram R, Yeung HW, Stroehlein JR, Macapinlac HA. Incidental finding of focal FDG uptake in the bowel during PET/CT: CT features and correlation with histopathologic results. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:W401–06. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozkol V, Alper E, Aydin N, Ozkol HF, Topal NB, Akpinar AT. The clinical value of incidental 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-avid foci detected on positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:128–36. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328332b30e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luboldt W, Volker T, Wiedemann B, Wehrmann U, Koch A, Toussaint T, et al. Detection of relevant colonic neoplasms with PET/CT: promising accuracy with minimal CT dose and a standardised PET cut-off. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2274–85. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng J, He Y, Xu J, Sheng J, Cai S, Zhang Z. Detection of incidental colorectal tumours with 18F-labelled 2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans: results of a prospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e374–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farquharson AL, Chopra A, Ford A, Matthews S, Amin SN, De Noronha R. Incidental focal colonic lesions found on (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan: further support for a national guideline on definitive management. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salazar Andía G, Prieto Soriano A, Ortega Candil A, Cabrera Martín MN, González Roiz C, Ortiz Zapata JJ, et al. Clinical relevance of incidental finding of focal uptakes in the colon during 18F-FDG PET/CT studies in oncology patients without known colorectal carcinoma and evaluation of the impact on management. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2012;31:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh JR, Min JJ, Song HC, Chong A, Kim GE, Choi C, et al. A stepwise approach using metabolic volume and SUVmax to differentiate malignancy and dysplasia from benign colonic uptakes on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:e134–40. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318239245d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin M, Ambati C. The management impact of clinically significant incidental lesions detected on staging FDG PET-CT in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an analysis of 649 cases. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildirim D, Tamam MO, Sahin M, Ekci B, Gurses B. Differentiation of incidental intestinal activities at PET/CT examinations with a new sign: Peristaltic segment sign. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2013;32:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill RS, Perry T, Abele JT, Bédard EL, Schiller D. The clinical significance of incidental intra-abdominal findings on positron emission tomography performed to investigate pulmonary nodules. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shim JH, O JH, Oh SI, Yoo HM, Jeon HM, Park CH, et al. Clinical Significance of Incidental Colonic (18)F-FDG Uptake on PET/CT Images in Patients with Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1847–53. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]