Abstract

Introduction

Whether early antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation could impact sexual risk behaviours remains to be documented. We aimed to investigate changes in sexual behaviours within the 24 months following an early versus standard ART initiation in HIV-positive adults with high CD4 counts.

Methods

We used data from a prospective behavioural study nested in a randomized controlled trial of early ART (Temprano-ANRS12136). Time trends in sexual behaviours from enrolment in the trial (M0) to 12-month (M12) and 24-month (M24) visits were measured and compared, using Generalized Estimating Equations models, between participants randomly assigned either to initiate ART immediately (early ART) or to defer ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria are met (standard ART). Indicators of sexual behaviours included 1) sexual activity in the past year, 2) multiple partnership in the past year, 3) unprotected sex at last intercourse and 4) risky sex (i.e. unprotected sex with a partner of HIV negative/unknown status) at last intercourse.

Results

Analyses included 1952 participants (975 with early ART and 977 with standard ART; overall median baseline CD4 count: 469/mm3). Among participants with early ART, significant decreases were found between M0 and M24 in sexual activity (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.72, 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI] 0.57–0.92), multiple partnership (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.41–0.79), unprotected sex (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.47–0.75) and risky sex (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45–0.76). Among participants with standard ART, sexual behaviours showed similar trends over time. These decreases mostly occurred within the 12 months following enrolment in the trial in both groups and prior to ART initiation in participants with standard ART. For unprotected sex and risky sex, decreases were or tended to be more pronounced among patients reporting that their last sexual partner was non-cohabiting.

Conclusions

In these sub-Saharan adults with high CD4 counts, entry into HIV care, rather than ART initiation, resulted in decreased sexual activity and risky sexual behaviours. We did not observe any evidence of a risk compensation phenomenon associated with early ART initiation. These results illustrate the potential behavioural preventive effect of early entry into care, which goes hand in hand with early ART initiation.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, antiretroviral treatment, sexual behaviours, early ART initiation, HIV prevention, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

With the preventive effect of early antiretroviral therapy (ART), demonstrated by the HPTN052 trial among stable serodiscordant couples [1], the Test and Treat prevention strategy appears as a promising way to curb the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. This strategy consists of universal HIV testing, coupled with immediate ART initiation in those diagnosed HIV positive, regardless of their CD4 count. Estimates of the preventive population-level impact of this strategy are mostly derived from models relying on the hypothesis, yet to be proven, that sexual behaviours would not change after early ART initiation [2, 3].

The possibility of risk compensation – increase in risk behaviours as a consequence of decreased perceived risks of HIV burden and/or transmission – may be of particular concern [4, 5]. Increase in sexual risk behaviours associated with ART initiation has been previously reported among high-risk groups early in the ART era [6, 7], and early models predicted that increases in risk behaviours associated with expanded ART could offset the preventive beneficial impact of ART [8, 9]. More recently, risk compensation has been suggested to explain the limited impact of ART for reducing HIV incidence in high-resource settings with high rates of HIV testing and treatment coverage [10]. However, such an effect of ART on sexual behaviours, if any, may vary depending on the context. According to a recent review of 17 observational studies conducted in resource-limited settings [11], only one study conducted in Côte d'Ivoire reported increased unprotected sex after ART initiation [12]. The remaining 16 studies documented decreased levels of sexual risk behaviours associated with ART initiation according to national or international guidelines. These results suggested a beneficial behavioural impact of treatment initiation. They did not investigate, though, whether this effect was due to ART itself or to entry into care.

To date, the consequences of ART initiation on sexual behaviours have mostly been studied in the context of standard ART initiation, that is, among patients with a clinically and/or biologically advanced HIV disease requiring treatment initiation as recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [13, 14]. Health status plays a central role in sexual behaviours, especially in the context of HIV infection [15–17]. Therefore, the effect of ART on sexual behaviours could be different when ART is started earlier, that is, in healthier patients potentially more sexually active. In addition, sexual and preventive behaviours, such as condom use or HIV status disclosure to partners, have been documented to differ according to the type of partnership [18–21], suggesting that ART initiation may have different consequences on sexual behaviours in the case of stable or occasional partnership.

We used data from the on-going Temprano ANRS-12136 randomized controlled trial to measure changes in sexual behaviours within the 24 months following early ART initiation and to compare these changes to those observed in patients starting ART according to WHO guidelines. We also investigated differences in sexual behaviours time trends according to the type of sexual partnership.

Material & Methods

Temprano ANRS-12136 trial

Temprano is a multicentre, randomized open-label superiority trial to assess the benefits and risks of initiating ART earlier than currently recommended by WHO, concomitantly or not with a six-month isoniazide prophylaxis for tuberculosis (IPT). The trial was launched in March 2008 in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, and is still on-going. It will end in December 2014. The trial protocol was approved by the Côte d'Ivoire national ethics committee and by the institutional review board of the French National Agency for Research on AIDS and viral hepatitis (ANRS, Paris, France). It has been registered on clinicaltrials.gov under the following identifier: NCT00495651.

Between March 2008 and July 2012, patients attending nine healthcare settings were included in the trial whenever they met the following criteria: informed consent signed; age >18 years; HIV-1-positive; no on-going active tuberculosis; no on-going pregnancy or breastfeeding; CD4 count <800/mm3 and no criteria for starting ART according to the most recent WHO guidelines. Participants were randomized into four arms: two “standard ART” arms (arms 1 and 2), in which ART was deferred until patients meet on-going WHO starting criteria [13, 14]; and two “early ART” arms (arms 3 and 4), in which ART was initiated immediately at enrolment. In arms 2 and 4, participants received a six-month IPT, starting at month-1 visit. Once included, participants were asked to show up for trial scheduled visits at day 8, month 1, month 2, month 3, and every three months thereafter. Standardized questionnaires were used to record baseline and follow-up characteristics. The trial sample included 2076 participants. Each participant will be followed-up during 30 months. The main outcome of the trial is the occurrence of a new episode of severe morbidity and any event leading to death.

Socio-behavioural study

The present socio-behavioural study was nested in the Temprano trial. Starting from 1st January 2010, standardized questionnaires were used to collect information on participants’ sexual behaviours during the past year and on the characteristics of their last sexual intercourse (type of partnership [cohabiting or not]; HIV status of the partner [negative, positive or unknown]; condom use). Questionnaires were administered face-to-face by trained interviewers at enrolment and at 12-month and 24-month visits except for delayed ART initiators in the standard ART arms who completed the questionnaire at enrolment, at ART initiation and then 12 months and 24 months after ART initiation. Patients included before January 2010, although they did not complete a socio-behavioural questionnaire at baseline, participated in the socio-behavioural study during their follow-up at the same tempo as those enrolled from 1st January 2010.

Study outcomes

Four indicators of sexual behaviours were considered: 1) sexual activity (i.e. at least one sexual intercourse) in the past year; 2) multiple partnership (i.e. at least two sexual partners) in the past year; 3) unprotected sex at last intercourse in the past year; and 4) risky sex (defined as unprotected sex with a partner of HIV negative/unknown status) at last intercourse in the past year.

Statistical analysis

All trial participants having completed a socio-behavioural questionnaire at one or more of the following trial visits were included in the present analysis: 1) M0 (inclusion visit), 2) M12 (12±3 months after inclusion) and 3) M24 (24±6 months after inclusion). For all analyses, participants of arms 1 and 2 were grouped together in a single group referred to as “standard ART” and participants of arms 3 and 4 were grouped together in a single group referred to as “early ART.”

Time trends in the four indicators of sexual behaviours from M0 to M12 and M24 visits were measured and compared between participants with early versus standard ART. To account for multiple observations per individual, marginal Generalized Estimating Equations models (GEE) of logistic regression assuming an exchangeable correlation structure were used. Covariates included in the models were ART group and time period, coded as a three-level factor in order to allow non-linear changes across time. An interaction term between ART group and time period was added to each model in order to assess differences in time trends according to ART strategy.

In order to investigate different patterns of sexual behaviours according to the type of partnership, we performed interaction tests to assess whether sexual behaviours trends over time differed between sexually active individuals with cohabiting vs. non-cohabiting partners.

Finally, in order to assess the role on behaviours changes of, respectively, entry into care and ART initiation, we described changes in sexual behaviours before versus after ART initiation among participants of the standard ART group. For this complementary analysis, we used GEE models including time periods coded as a four-level factor: 1) M0 (inclusion visit), 2) TI (at Treatment Initiation, allowing for a varying time period between M0 and TI for each individual), 3) TI+12 (12±3 months after TI), and 4) TI+24 (24±6 months after TI).

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 1952 participants (standard ART: 977; early ART: 975) completed at least one socio-behavioural questionnaire in due time and were included in the present analysis, accounting for a total of 3364 questionnaires (standard ART: 1653; early ART: 1711). As of March 1st, 2013, participants had been followed during a mean time of 25.7 months (Interquartile Range [IQR]: 23.9–30.0), and 57% of participants had completed at least two socio-behavioural questionnaires, with no difference between both ART groups (Supplementary file).

Median age at baseline was 35 years and 79% of participants were women. Median baseline CD4 cell count was 469/mm3 (IQR 379–577). No significant difference in baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics was observed between patients of standard vs. early ART groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants of standard and early antiretroviral therapy (ART) groups

| Standard ART | Early ART | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.31 | ||

| Men | 219 (22.4%) | 200 (20.5%) | |

| Women | 758 (77.6%) | 775 (79.5%) | |

| Age | 35 [30–42] | 35 [30–42] | 0.69 |

| Educational level | 0.61 | ||

| None | 236 (24.2%) | 257 (26.4%) | |

| Primary | 281 (28.7%) | 276 (28.3%) | |

| Secondary | 327 (33.5%) | 324 (33.2%) | |

| > Secondary | 133 (13.6%) | 118 (12.1%) | |

| Personal source of income | 0.35 | ||

| No | 238 (25.4%) | 256 (27.3%) | |

| Yes | 700 (74.6%) | 682 (72.7%) | |

| Family status | 0.57 | ||

| Single | 417 (42.7%) | 414 (42.5%) | |

| Living in union | 460 (47.1%) | 447 (45.8%) | |

| Separated/widowed | 100 (10.2%) | 114 (11.7%) | |

| HIV-status disclosure to the partner | 0.92 | ||

| No | 467 (52.0%) | 467 (52.2%) | |

| Yes | 432 (48.0%) | 428 (47.8%) | |

| WHO clinical stage | 0.88 | ||

| 1 | 632 (64.8%) | 622 (63.8%) | |

| 2 | 252 (25.8%) | 262 (26.9%) | |

| 3 | 86 (8.8%) | 87 (8.9%) | |

| 4 | 6 (0.6%) | 4 (0.4%) | |

| CD4 count cell (/mm3) | 470 [375–573] | 468 [384–580] | 0.48 |

Socio-behavioural study nested in the Temprano Trial (N=1952); patients in the standard ART group deferred ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria were met, whereas patients in the early ART group initiated ART immediately on inclusion in the trial; counts (%) and Chi-squared p-values are presented for categorical measures. Percentages are computed as fractions of non-missing observations. Medians (interquartile ranges) and t-test p-values are presented for quantitative measures.

Sexual behaviours within the 24 months following inclusion

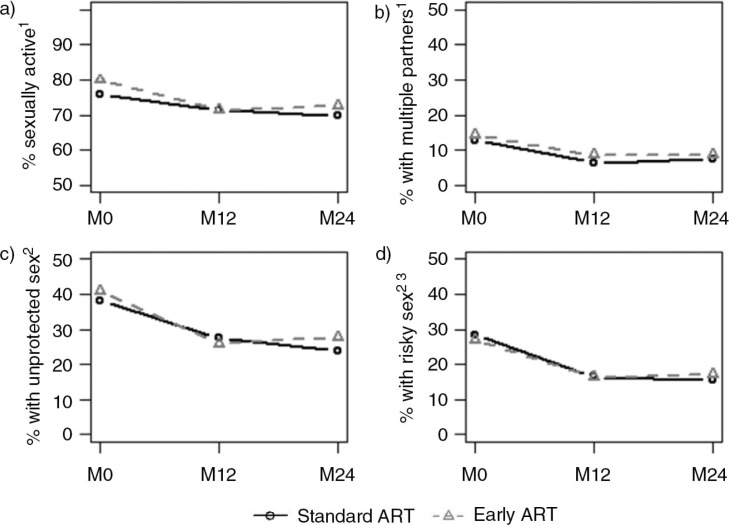

The frequency of sexual activity decreased from 79.9% at M0 to 72.6% at M24 among participants with early ART and from 75.9 to 69.8% among participants with standard ART (Figure 1a). At the same time, the frequency of multiple partnership decreased from 14.4 to 8.7% in the early ART group and from 12.8 to 7.6% in the standard ART group (Figure 1b). Frequencies of unprotected sex were 40.7% among participants with early ART and 38.1% among those with standard ART at baseline, decreasing to 27.3 and 23.9%, respectively, at M24 (Figure 1c). The frequency of risky sex decreased from 26.8% at M0 to 17.3% at M24 among participants with early ART and from 28.4% at M0 to 15.5% at M24 among participants with standard ART (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Sexual behaviours reported at inclusion (M0), 12-month visit (M12) and 24-month visit (M24) among participants of standard and early antiretroviral therapy (ART) groups. Socio-behavioural study nested in the Temprano Trial (N=1952).

Patients in the standard ART group deferred ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria were met, whereas patients in the early ART group initiated ART immediately on inclusion in the trial.

1In the past year.

2At last intercourse in the past year.

3Defined as an unprotected intercourse with a partner of negative/unknown HIV status.

As shown in Table 2, frequencies of sexual activity, multiple partnership, unprotected sex and risky sex significantly decreased between M0 and M12 in both ART groups (each Odds Ratio [OR] comparing M12 to M0 taking a value of less than 1, with corresponding p<0.01); with the exception of sexual activity in the standard ART group, which showed borderline significant decrease over time (ORM12 vs. M0 0.80; 95% Confidence Interval [95%CI] 0.64–1.01]). Subsequently, for the four indicators, the frequencies did not significantly change between M12 and M24 (each p >0.05).

Table 2.

Time trends in sexual behaviour indicators within 24 months following enrolment in the trial among participants of standard and early antiretroviral therapy (ART) groups

| Standard ART | Early ART | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t 1 to t 2 | % changeb | OR (t2 vs. t1)c |

95% CI | p | % changeb | OR (t2 vs. t1)c |

95% CI | p | Interaction p a |

| Sexual activityd | 0.61 | ||||||||

| M0 to M24 | −6.1 | 0.76 | [0.59; 0.96] | 0.022 | −7.3 | 0.72 | [0.57; 0.92] | 0.008 | |

| M0 to M12 | −4.4 | 0.80 | [0.64; 1.01] | 0.062 | −8.5 | 0.70 | [0.57; 0.87] | 0.002 | |

| M12 to M24 | −1.7 | 0.94 | [0.79; 1.11] | 0.45 | +1.2 | 1.03 | [0.87; 1.22] | 0.77 | |

| Multiple partnershipd | 0.64 | ||||||||

| M0 to M24 | −5.2 | 0.55 | [0.38; 0.80] | 0.002 | −5.7 | 0.57 | [0.41; 0.79] | <10−3 | |

| M0 to M12 | −6.4 | 0.49 | [0.34; 0.70] | <10−3 | −5.8 | 0.60 | [0.44; 0.83] | 0.002 | |

| M12 to M24 | +1.2 | 1.13 | [0.78; 1.64] | 0.48 | +0.1 | 0.94 | [0.69; 1.27] | 0.63 | |

| Unprotected sexe | 0.16 | ||||||||

| M0 to M24 | −14.2 | 0.50 | [0.39; 0.64] | <10−3 | −13.4 | 0.59 | [0.47; 0.75] | <10−3 | |

| M0 to M12 | −10.5 | 0.61 | [0.48; 0.78] | <10−3 | −14.7 | 0.55 | [0.43; 0.70] | <10−3 | |

| M12 to M24 | −3.7 | 0.83 | [0.68; 1.01] | 0.06 | +1.3 | 1.09 | [0.89; 1.32] | 0.41 | |

| Risky sexe,f | 0.56 | ||||||||

| M0 to M24 | −12.9 | 0.48 | [0.36; 0.63] | <10−3 | −9.5 | 0.58 | [0.45; 0.76] | <10−3 | |

| M0 to M12 | −11.8 | 0.52 | [0.39; 0.69] | <10−3 | −10.4 | 0.55 | [0.42; 0.72] | <10−3 | |

| M12 to M24 | −1.1 | 0.93 | [0.74; 1.17] | 0.52 | +0.9 | 1.06 | [0.84; 1.34] | 0.64 | |

Socio-behavioural study nested in the Temprano Trial (N=1952); patients in the standard ART group deferred ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria were met, whereas patients in the early ART group initiated ART immediately on inclusion in the trial

p-value of the overall likelihood-ratio test for interaction between ART group and time (for the whole M0–M24 period)

change in percentage points between t1 and t2

odds ratio of reporting the corresponding sexual behaviour at t2 as compared to t1 (logistic regression model with Generalized Estimating Equations)

in the past year

at last intercourse in the past year

defined as an unprotected intercourse with a partner of negative/unknown HIV status; M0: at inclusion in the trial; M12: 12 months after inclusion; M24: 24 months after inclusion; OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval.

No significant interaction between study group and time was found for any of the four sexual behaviours indicators (each p>0.15), suggesting that time trends between M0 and M24 in these various indicators did not significantly differ across ART strategies.

A complementary analysis was conducted, restricting the GEE analysis 1) to sexually active participants and 2) to participants reporting no condom use at last intercourse. In both cases, the decrease in risky sex between M0 and M12 remained statistically significant (data not shown).

Differences according to the type of partnership

Among sexually active participants, the overall proportion reporting that their last partner was non-cohabiting was 39.9% at M0; 40.1% at M12; and 42.7% at M24. These proportions were higher among women than men (overall, 44.8% vs. 28.5%, p<10−3).

Regardless of ART strategy and type of partnership, frequencies of multiple partnership, unprotected sex and risky sex decreased between M0 and M12 (Table 3). For unprotected sex and risky sex, these decreases were or tended to be more pronounced among participants reporting a non-cohabiting partner at last intercourse (ORM12 vs. M0 between 0.36 and 0.42) than among those reporting a cohabiting partner (ORM12 vs. M0 between 0.60 and 0.77). This differential decrease was not observed for multiple partnerships.

Table 3.

Time trends in sexual behaviours indicators within 24 months following enrolment in the trial among participants of standard and early antiretroviral therapy (ART) groups, by type of partnership

| Standard ART | Early ART | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Cohabiting partner | Non-cohabiting partner | Cohabiting partner | Non-cohabiting partner | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| OR (t2 vs. t1)b |

95% CI | p | OR (t2 vs. t1)b |

95% CI | p | Interaction p a | OR (t2 vs. t1)b |

95% CI | p | OR (t2 vs. t1)b |

95% CI | p | Interaction p a | |

| Multiple partnershipc | 0.92 | 0.48 | ||||||||||||

| M0 to M12 | 0.44 | [0.23; 0.84] | 0.013 | 0.52 | [0.31; 0.87] | 0.012 | 0.59 | [0.36; 0.96] | 0.033 | 0.64 | [0.39; 1.05] | 0.07 | ||

| M12 to M24 | 1.22 | [0.64; 2.32] | 0.55 | 1.16 | [0.69; 1.94] | 0.57 | 0.70 | [0.39; 1.23] | 0.21 | 0.98 | [0.62; 1.54] | 0.93 | ||

| Unprotected sexd | 0.038 | 0.15 | ||||||||||||

| M0 to M12 | 0.77 | [0.54; 1.10] | 0.15 | 0.41 | [0.26; 0.64] | <.001 | 0.68 | [0.48; 0.95] | 0.023 | 0.41 | [0.26; 0.66] | <10−3 | ||

| M12 to M24 | 0.68 | [0.52; 0.89] | <.001 | 1.18 | [0.79; 1.77] | 0.43 | 1.11 | [0.84; 1.46] | 0.48 | 1.10 | [0.72; 1.66] | 0.67 | ||

| Risky sexd,e | 0.27 | 0.048 | ||||||||||||

| M0 to M12 | 0.60 | [0.42; 0.86] | 0.006 | 0.42 | [0.26; 0.68] | <.001 | 0.77 | [0.56; 1.07] | 0.12 | 0.36 | [0.22; 0.60] | <10−3 | ||

| M12 to M24 | 0.78 | [0.59; 1.03] | 0.08 | 1.16 | [0.76; 1.78] | 0.48 | 0.94 | [0.69; 1.28] | 0.68 | 1.33 | [0.85; 2.09] | 0.21 | ||

Socio-behavioural study nested in the Temprano Trial (N=1642 sexually active participants); patients in the standard ART group deferred ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria were met, whereas patients in the early ART group initiated ART immediately on inclusion in the trial

p-value of the overall likelihood-ratio test for interaction between type of partnership and time (for the whole M0–M24 period)

odds ratio of reporting the corresponding sexual behavior at t2 as compared to t1 (logistic regression model with Generalized Estimating Equations)

in the past year

at last intercourse in the past year

defined as an unprotected intercourse with a partner of negative/unknown HIV status; M0: at inclusion in the trial; M12: 12 months after inclusion; M24: 24 months after inclusion, OR: Odds Ratio: CI: Confidence Interval.

Subsequently, frequencies of multiple partnership, unprotected sex and risky sex generally did not significantly change between M12 and M24, regardless of ART group and type of partnership. The only exception was a significant decrease between M12 and M24 in the frequency of unprotected sex among participant of the standard ART group reporting a cohabiting partner at last intercourse.

Sexual behaviours before/after ART initiation among participants on standard ART

A total of 802 participants of the standard ART group completed at least one socio-behavioural questionnaire at the following time points: M0, treatment initiation (TI), 12 months after TI (TI+12) and 24 months after TI (TI+24), representing a total of 1455 questionnaires. Among them, 492 initiated ART (median time between enrolment and treatment initiation: 14.0 months [IQR 8.0–20.1]).

Among these 802 participants, the frequency of sexual activity did not significantly change over time between M0 and TI+24 (Table 4). In contrast, frequencies of multiple partnership, unprotected sex and risky sex significantly decreased between M0 and treatment initiation (multiple partnership: ORTI vs. M0 0.41, 95%CI 0.26–0.64; unprotected sex: ORTI vs. M0 0.65, 95%CI 0.49–0.85; risky sex: ORTI vs. M0 0.62, 95%CI 0.45–0.84). Subsequently, the frequencies of these three indicators did not significantly change over time within the 24 months following treatment initiation (each p>0.15).

Table 4.

Time trends in sexual behaviours indicators before and after standard antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation among participants of the standard ART group

| Sexual activitya | Multiple partnershipa | Unprotected sexb | Risky sexb,c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| OR (t2 vs. t1)d |

95% CI | p | OR (t2 vs. t1)d |

95% CI | p | OR (t2vs. t1)d |

95% CI | p | OR (t2vs. t1)d |

95% CI | p | |

| M0 to TI | 0.91 | [0.70; 1.19] | 0.50 | 0.41 | [0.26; 0.64] | <10−3 | 0.65 | [0.49; 0.85] | 0.002 | 0.62 | [0.45; 0.84] | 0.002 |

| TI to TI+12 | 0.96 | [0.76; 1.21] | 0.73 | 0.98 | [0.55; 1.72] | 0.93 | 1.08 | [0.84; 1.37] | 0.56 | 0.91 | [0.68; 1.21] | 0.52 |

| TI+12 to TI+24 | 0.96 | [0.78; 1.18] | 0.68 | 0.65 | [0.34; 1.23] | 0.19 | 0.86 | [0.70; 1.09] | 0.22 | 0.88 | [0.67; 1.15] | 0.35 |

Socio-behavioural study nested in the Temprano Trial (N=802); patients in the standard ART group deferred ART initiation until on-going WHO starting criteria were met

in the past year

at last intercourse in the past year

defined as an unprotected intercourse with a partner of negative/unknown HIV status

odds Ratio of reporting the corresponding sexual behavior at t2 as compared to t1 (logistic regression model with Generalized Estimating Equations); M0: at inclusion in the trial; TI: at treatment initiation; TI+12:12 months after ART initiation; TI+24:24 months after ART initiation; OR: Odds Ratio: CI: Confidence Interval.

Discussion

In this study nested in an on-going randomized controlled trial of early ART, we found decreases in several reported sexual behaviours within the 24 months following inclusion. These decreases mostly occurred within the first 12 months following enrolment in the trial in both groups and prior to ART initiation in participants with standard ART. They did not differ between participants initiating ART early and those deferring ART according to WHO recommendations, suggesting that such time trends might be a result of early entry into care rather than ART initiation (whether early or not). In addition, regardless of ART strategy, decreases in two sexual risk behaviours indicators, namely unprotected sex and risky sex, tended to be more pronounced for patients reporting non-cohabiting partners as compared to those in cohabiting partnership.

Sexual behaviours in the context of HIV care have been previously investigated in Côte d'Ivoire. Three studies conducted among HIV-positive patients, both treated and untreated, documented levels of sexual activity in the past six months ranging approximately from 50 to 65% [12, 22, 23]. The higher level of sexual activity (71%) during the past year reported in the present study may be explained by a longer recall period. It may additionally be related to the better health status of our study population, made of patients recruited at an early stage of HIV disease. Previous studies also reported levels of unprotected sex, as measured by inconsistent condom use, ranging from 20 to 30% [12, 22, 23]. This is consistent with the 25% participants reporting unprotected sex at last intercourse in our study.

Four indicators of sexual behaviours were used in this study. Among these, risky sex (i.e. unprotected sex with a partner of HIV negative/unknown status) may be considered as the best proxy of partner's exposure to HIV infection. In both ART groups, the odds-ratio of reporting risky sex at last intercourse at M24, as compared to M0, was close to 0.5. This approximately represents, when accounting for the prevalence of risky sex, a 40% decrease at the population level [24]. This indicator integrates different components: sexual activity, condom use and partner's HIV status. Complementary analyses suggested that this time trend reflected not only a decrease in overall sexual activity but also an increase in condom use and in knowledge of partner's HIV status over time. Decrease in sexual activity, number of sexual partners or unprotected intercourses have previously been reported in the context of biomedical prevention trials [25–27]. At the community level, a substantial increase in condom use has also been recently documented in South Africa during ART coverage scale-up [28].

At each time step considered, we found that sexual behaviours did not differ according to ART strategy. This finding might challenge the results of several literature reviews, which pointed out decreased sexual risk behaviours associated with ART initiation [11, 29–31]. However, previous studies relied on comparisons between ART-treated versus untreated patients in a context where routine contacts with the care system are generally infrequent for patients not yet ART-eligible [32]. It has been previously suggested that the behavioural effect of ART may be due to frequent contact with the healthcare system rather than to ART itself, considering that attendance to care provides counselling and psychosocial support [23, 33]. The similar decreases in risk behaviours we found in both ART groups, as well as the absence of additional decrease after treatment initiation in the standard ART group support this hypothesis. Actually, in the Temprano trial the frequency of clinic visits is the same for all participants, regardless of trial arm. Besides, the protocol did not include any additional intervention to reduce risk behaviours apart from routine clinic-based HIV counselling. Our results thus suggest that, as compared to an entry into standard care at early stage of the HIV-infection, early ART initiation per se did not differently impact sexual behaviours.

The dynamics of the changes in sexual behaviours found in this study is consistent with previous results. A study conducted in Uganda indicated a dramatic decrease in unprotected sex at last intercourse during the first year following standard ART initiation, and then a stabilized level during the two subsequent years [34]. Our findings suggest that changes in sexual behaviours occur immediately after inclusion in the trial. These changes might integrate modifications in sexual behaviours resulting from the announcement of HIV diagnosis [35, 36] – which probably occurred shortly before enrolment in our study population with high baseline CD4 levels. Subsequently, after 12 months of follow-up, we did not observe further decrease in sexual behaviours indicators. Neither did we observe any “prevention fatigue” (i.e. a decrease in preventive behaviours over time) as previously reported among high-risk groups [37]. However, our results were obtained within a relatively short follow-up time (24 months). Further studies are needed to measure long term changes in sexual behaviours after early entry into care.

We additionally found that decreases in sexual risk behaviours were more pronounced among patients reporting that their last sexual partner was non-cohabiting versus cohabiting. This differential decrease may reflect a lower level of condom use among cohabiting versus non-cohabiting – or respectively spousal and non-spousal – relationships, as observed in other African settings [19, 20]. It may also reflect the fact that it is more difficult to modify sexual behaviours once they are already established in a couple. In both cases, these results underline the need for specific prevention messages oriented towards well-established couples.

Our results also provide insights into the issue of risk compensation. We did not find any increase in sexual risk behaviours as a result of early ART initiation, an intervention conferring a strong preventive effect against HIV transmission. Actually, we found that sexual risk behaviours were similar whether participants received the intervention or not, and that levels of risk behaviours decreased rather than increased following inclusion in the trial, regardless of ART strategy. These findings, although they provide evidence against the existence of a phenomenon of risk compensation associated with early ART initiation, must be interpreted with caution. Temprano is a clinical trial which primary objective is to measure the individual rather than collective benefits and risks of early ART. Thus, before the implementation of the 2012 WHO guidelines [38], no specific information on the preventive effects of ART was provided to trial participants. Whether participants have received this information from other sources of information following the publication and media exposure of the HPTN052 trial results [1] is unknown.

To our knowledge, this study is the first one to prospectively document detailed sexual behaviours following early ART initiation. Its major strengths are the large and randomized nature of the datasets. However, we acknowledge that our results may be subject to some biases. First, this study relies on self-reported sexual behaviours, which may have been under-reported as a result of social desirability. In order to prevent such a bias, interviewers were trained to administer questionnaires in a non-judgmental way and interviews were conducted confidentially in private rooms. In addition, a literature meta-analysis showed that a face-to-face interview does not always yield to lower estimates of sexual risk behaviours as compared to alternative interviewing tools [39]. Actually, we found higher levels of sexual activity than previous studies conducted among HIV-positive patients in Côte d'Ivoire [12, 22, 23]. This suggests that our results are unlikely to be explained by this sole bias. Second, given the design of the study, it is difficult to disentangle the effect of entry into care from that of enrolment in the trial to explain our results. Of note, Temprano is not a prevention trial but a clinical trial in which only conventional HIV counselling as provided in routine HIV care is offered. Besides, our sample was made of patients recruited in nine clinical centres reflecting the diversity of HIV care offered in Abidjan (hospitals, private clinics, NGO and primary care centres). In each participating centre, all eligible patients were systematically approached to participate in the trial. The total refusal rate was quite low (16%), indicating a limited selection bias. Taken together, these arguments suggest that the trends in sexual behaviours we describe here are also likely to be observed after early entry into care in “real world” settings.

Conclusions

Through its biological effect, early ART initiation reduces the risk of transmitting HIV from HIV-positive individuals to their sexual partners, which has been documented among the same study population [40]. The present study did not document any evidence of a risk compensation phenomenon associated with early ART initiation. Our results rather suggest that early entry into care, which goes hand in hand with early ART initiation, also carries a substantial behavioural preventive effect. This underlines that, concurrently with the prevention potential of ART, conventional interventions targeting behaviours still have a role to play within combined prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all patients who participated in this trial.

We are grateful for the valuable contributions of the SMIT, CeDReS, CEPREF, USAC, CIRBA, CNTS, La Pierre Angulaire, Hôpital Général Abobo, Formation Sanitaire Anonkoua Kouté, Centre de santé El Rapha, Programme PACCI and INSERM U897 teams: Abanou Matthieu, Aman Adou, Anasthasie Yapo, Bombo Léontine, Célestin N'chot, Christian Kouadio, Djetouan Hugues, Djobi-Djo Edouard, Goly Jocelyn, Kassi Marie-Cécile, Koffi- N'Dri Aholi, Konan Sylvie, Konaté Mamadou, Kouadio Bertin, Kouamé Martin, Kouadio Victoire, Kouakou-Aboua Adrienne, Kouakou Yao, Kouamé Antoine, Kouamé Ferdinand, Kouamé Gérald, Labibi Georgette, Lokou Benjamin, Moh Jules, N'Dri Marie Julie, Nalourgou Tuo, N'Goran Brou, Nogbout Marie-Pascale, Orne-Gliemann Joanna, Kouadio Cheftin, Ouattara Minata, Oupoh Joséphine, Sidibé Abdelh, Siloué Bertine, Soro Adidiata, Tchehy Amah-Cécile, Yao Emile and Yao Juliette.

We thank Gilead Sciences for the donation of Truvada®, and Merck Sharp & Dohme for the donation of Stocrin.®

Members of the ANRS 12136 Temprano trial Group:

Clinical care in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

Service des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales (SMIT): Emmanuel Bissagnene, Serge Eholie (principal investigator), Gustave Nzunetu, Cyprien Rabe and Sidibé Baba.

Centre Intégré de Recherches Biocliniques d'Abidjan (CIRBA): Olivier Ba-Gomis, Henri Chenal, Marcelle Daligou and Denise Hawerlander.

Centre National de Transfusion Sanguine (CNTS): Lambert Dohoun, Seidou Konate, Albert Minga and Abo Yao.

Unité de Soins Ambulatoires et de Conseil (USAC): Constance Kanga, Koulé Serge, Jonas Séri, Calixte Guéhi and Fassiri Dembélé.

Centre de Prise en Charge et de Formation (CePReF): Eugène Messou, Amani Anzian, Joachim Gnokoro and Patrice Gouessé.

La pierre angulaire: Madeleine Kadio-Morokro, Alain Kouadio, Séna Gountodji, Ediga Yédjédji and Alexis Amian

Hôpital Général Abobo Nord: Emmanuel Kouamé, Dominique Koua, Solange Amon, Laurent Dja-Beugré and Amadou Kouamé

FSU Anonkoua kouté: Oyéounlé Makaïla, Mounkaila Oyébi, Stanislas Sodenougbo andNathalie Mbakop

Centre de santé El Rapha: Babatundé Natanael, Babatundé Carolle, Gisèle Bléoué and Mireille Tchoutchedjem

Biology: Centre de Diagnostic et de Recherches sur le SIDA (CeDReS), CHU de Treichville, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire: Matthieu Kabran (bacteriologist), Arlette Emieme (monitor), André Inwoley (immunologist), Hervé Menan (parasitologist), Timothée Ouassa (bacteriologist), Thomas-d'Aquin Toni (virologist) and Vincent Yapo (virologist); Service de Virologie, CHU Necker, Paris, France: Marie-Laure Chaix (virologist) and Christine Rouzioux (virologist).

Trial coordination team: Programme PACCI, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire: Xavier Anglaret (principal investigator), Christine Danel (coordinator), Raoul Moh (coordinator), Romuald Konan (pharmacist), Anani Badjé (monitor), Jean Baptiste N'takpé (monitor), Gérard Menan Kouamé (monitor), Franck Bohoussou (data manager); Centre Inserm 897, Bordeaux, France: Delphine Gabillard (statistician), Jérôme Le Carrou (monitor).

Trial Steering Committee: Jean-Marie Massumbuko, Emmanuel Bissagnene, Géneviève Chêne, Kouao Domoua, Mireille Dosso, Pierre-Marie Girard, Vincent Jarlier, Christian Perronne, Christine Rouzioux, Papa Salif Sow and Virginie Ettiegne-Traoré.

Trial Independent Data Safety Monitoring Board: François-Xavier Blanc, Dominique Costagliola, Brigitte Autran, Ogobara Doumbo, Sinata Koula-Shiro, Souleymane Mboup, Yazdan Yazdanpanah

Representatives of the French Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS, Paris, France): Jean-François Delfraissy, Brigitte Bazin, Claire Rekacewicz and Géraldine Colin.

Funding support

This trial was supported by a grant from the French Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA et les hépatites virales (ANRS, Paris, France; grants ANRS 12136 and ANRS 12239) (Clinical Trial Number: NCT00495651).

The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

To access the supplementary material to this article please see Supplementary Files under Article Tools online.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any commercial or other associations that constitute competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RM, CD, ADL, SE and XA designed the trial. RM, CD, JBN, JLC, AB and XA collected the data. KJ, DG, FL and RDS conceived and designed the analysis. KJ conducted the analysis. KJ, FL and RDS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DG, RM, CD, ADL, JBN, JLC, AB, SE and XA contributed to the manuscript's review and edition. All authors have read and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eaton JW, Johnson LF, Salomon JA, Bärnighausen T, Bendavid E, Bershteyn A, et al. HIV treatment as prevention: systematic comparison of mathematical models of the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV incidence in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassell MM, Halperin DT, Shelton JD, Stanton D. Risk compensation: the Achilles’ heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ. 2006;332(7541):605–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7541.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaton LA, Kalichman S. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):165–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dukers NH, Goudsmit J, de Wit JB, Prins M, Weverling GJ, Coutinho RA. Sexual risk behaviour relates to the virological and immunological improvements during highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001;15(3):369–78. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tun W, Gange SJ, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. Increase in sexual risk behavior associated with immunologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(8):1167–74. doi: 10.1086/383033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law MG, Prestage G, Grulich A, Van de Ven P, Kippax S. Modelling the effect of combination antiretroviral treatments on HIV incidence. AIDS. 2001;15(10):1287–94. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velasco-Hernandez JX, Gershengorn HB, Blower SM. Could widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy eradicate HIV epidemics? Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(8):487–93. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson DP. HIV treatment as prevention: natural experiments highlight limits of antiretroviral treatment as HIV prevention. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesh KK, Flanigan TP, Mayer KH. Is expanded HIV treatment preventing new infections? Impact of antiretroviral therapy on sexual risk behaviours in the developing world. AIDS. 2011;25(16):1939–49. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b4ced. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabaté S, Alary M, Koffi CK. Short-term increase in unsafe sexual behaviour after initiation of HAART in Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2008;22(1):154–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f029e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2006. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach: 2006 revision. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 revision. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW, Lekas H-M. Diminished sexual activity, interest, and feelings of attractiveness among HIV-infected women in two eras of the AIDS epidemic. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35(4):437–49. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9043-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarna A, Chersich M, Okal J, Luchters SMF, Mandaliya KN, Rutenberg N, et al. Changes in sexual risk taking with antiretroviral treatment: influence of context and gender norms in Mombasa, Kenya. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11(8):783–97. doi: 10.1080/13691050903033423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGrath N, Richter L, Newell M-L. Sexual risk after HIV diagnosis: a comparison of pre-ART individuals with CD4 > 500 cells/(l and ART-eligible individuals in a HIV treatment and care programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18048. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adrien A, Leaune V, Dassa C, Perron M. Sexual behaviour, condom use and HIV risk situations in the general population of Quebec. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(2):108–15. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, Kim JC, Busza J, Phetla G, Porter JDH, et al. Characteristics of sexual partnerships, not just of individuals, are associated with condom use and recent HIV infection in rural South Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21(8):1058–70. doi: 10.1080/09540120802657480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vu L, Andrinopoulos K, Mathews C, Chopra M, Kendall C, Eisele TP. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners among HIV-infected men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):132–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9873-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moatti J-P, Prudhomme J, Traore DC, Juillet-Amari A, Akribi HA-D, Msellati P. Access to antiretroviral treatment and sexual behaviours of HIV-infected patients aware of their serostatus in Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2003;3(17 Suppl):S69–77. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Protopopescu C, Marcellin F, Préau M, Gabillard D, Moh R, Minga A, et al. Psychosocial correlates of inconsistent condom use among HIV-infected patients enrolled in a structured ART interruptions trial in Côte d'Ivoire: results from the TRIVACAN trial (ANRS 1269) Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(6):706–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies HTO, Crombie IK, Tavakoli M. When can odds ratios mislead? BMJ. 1998;316(7136):989–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7136.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, Akumatey B, Clarke EEK, Chen P-L, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior among participants in a PrEP HIV prevention trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(12):1002–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of Tenofovir Gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGrath N, Eaton JW, Bärnighausen TW, Tanser F, Newell M-L. Sexual behaviour in a rural high HIV prevalence South African community: time trends in the antiretroviral treatment era. AIDS. 2013;27(15):2461–70. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432473.69250.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy C, O'Reilly K, Medley A, Sweat M. The impact of HIV treatment on risk behaviour in developing countries: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):707–20. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berhan A, Berhan Y. Is the sexual behaviour of HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy safe or risky in Sub-Saharan Africa? Meta-analysis and meta-regression. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaye DK, Kakaire O, Osinde MO, Lule JC, Kakande N. The impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on high-risk behaviour of HIV-infected patients in sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(6):436–47. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8(7):e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarna A, Luchters SMF, Geibel S, Kaai S, Munyao P, Shikely KS, et al. Sexual risk behaviour and HAART: a comparative study of HIV-infected persons on HAART and on preventive therapy in Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(2):85–9. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wandera B, Kamya MR, Castelnuovo B, Kiragga A, Kambugu A, Wanyama JN, et al. Sexual behaviours over a 3-year period among individuals with advanced HIV/AIDS receiving antiretroviral therapy in an urban HIV clinic in Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(1):62–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318211b3f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1397–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fonner VA, Denison J, Kennedy CE, O'Reilly K, Sweat M. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD001224. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001224.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostrow DE, Fox KJ, Chmiel JS, Silvestre A, Visscher BR, Vanable PA, et al. Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS. 2002;16(5):775–80. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012. Guidance on couples HIV testing and counseling including antiretroviral therapy for treatment as prevention in serodiscordant couples. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips AE, Gomez GB, Boily M-C, Garnett GP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools to investigate self-reported HIV and STI associated behaviours in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1541–55. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jean K, Gabillard D, Moh R, Danel C, Fassassi R, Desgrees-du-Lou A, et al. Effect of early antiretroviral therapy on sexual behaviours and HIV-1 transmission risk in adults with diverse heterosexual partnership status in Côte d'Ivoire. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):431–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]