Abstract

Objective

Quality indicators for the treatment of type 2 diabetes are often retrieved from a chronic disease registry (CDR). This study investigates the quality of recording in a general practitioner's (GP) electronic medical record (EMR) compared to a simple, web-based CDR.

Methods

The GPs entered data directly in the CDR and in their own EMR during the study period (2011). We extracted data from 58 general practices (8235 patients) with type 2 diabetes and compared the occurrence and value of seven process indicators and 12 outcome indicators in both systems. The CDR, specifically designed for monitoring type 2 diabetes and reporting to health insurers, was used as the reference standard. For process indicators we examined the presence or absence of recordings on the patient level in both systems, for outcome indicators we examined the number of compliant or non-compliant values of recordings present in both systems. The diagnostic OR (DOR) was calculated for all indicators.

Results

We found less concordance for process indicators than for outcome indicators. HbA1c testing was the process indicator with the highest DOR. Blood pressure measurement, urine albumin test, BMI recorded and eye assessment showed low DOR. For outcome indicators, the highest DOR was creatinine clearance <30 mL/min or mL/min/1.73 m2 and the lowest DOR was systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg.

Conclusions

Clinical items are not always adequately recorded in an EMR for retrieving indicators, but there is good concordance for the values of these items. If the quality of recording improves, indicators can be reported from the EMR, which will reduce the workload of GPs and enable GPs to maintain a good patient overview.

Keywords: Data Quality, Electronic Medical Record, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Quality of Care, Quality Indicators

Background and significance

From 2005, the Dutch government enacted legislation in order to introduce market forces in healthcare,1–3 implementing the model of regulated competition by Alain Enthoven.3 In market-driven healthcare, it is assumed that consumers and insurers want value for money, therefore they need insight in healthcare performance, that is, in transparency of costs in relation to the quality of care.3 4 It is often assumed that quality of care can be assessed by quality indicators, which are aspects of healthcare that both provide insight into the quality of care and that can be measured.5 Indicators can be selected on the basis of several criteria, for example, clinical relevance, clinimetric properties as reliability and validity, feasibility of recording and extracting, room for improvement, accordance to national guidelines, and relevance for and acceptability by different target audiences such as patients.6 7

Within Dutch primary care, market forces lead to the formation of so-called ‘care groups’, in which caregivers cooperate in the treatment of specific chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.8 Care groups are subsequently funded as a single unit by health insurers.8–10 Both insurance companies and care groups need good indicators to contract and negotiate on the basis of quality,4 10 because in the near future (primary) care groups and insurers will use indicators in order to negotiate the level of reimbursement of care provided as a standard set of care products, a ‘care pathway’,4 11 with an accompanying price.4 9 12 This will guard patients’ access to high quality healthcare for an affordable price in an ageing population. Therefore, various national sets of indicators for type 2 diabetes have been developed, which all distinguish between at least two types of indicators: process indicators and outcome indicators.5 13 Process indicators reflect whether a caregiver executed specific healthcare activities, outcome indicators reflect the effect of these activities on the patient's health.14

These indicators can be recorded in two different types of medical information systems: a chronic disease registry (CDR) or an electronic medical record (EMR). CDR are used by care groups for disease management.15 16 A CDR is a system that is used for monitoring the process and outcome of a specific chronic disease, with the benefits of easy and uniform data entering, easy data extraction and good patient overview and management.16 17 In The Netherlands, CDR are used by care groups for audit and feedback to participating practices, payment to the associated general practices and for reporting to health insurers, while general practices use EMR to record care for all complaints and diseases of all patients. Practically all Dutch general practitioners (GPs) use EMR, which makes The Netherlands one of the leading countries in the use of these records when compared to other countries such as the USA.18 19 In The Netherlands, a patient generally first contacts the GP, who will refer the patient to other medical disciplines if necessary.

Currently, in primary care indicators are mainly recorded in CDR. However, as GPs also continue to use their own EMR, there is double recording. This is undesirable, because recording takes time, time during which no care can be administered. As more diseases become funded via primary care groups,8 the load of double recording will increase. Subsequently, the need arises to record items in a single source, from which indicators can be deduced indirectly. An obvious source would be the GP's own EMR, because thereby the GP can guard the coordination of health problems on the patient level.15

If EMR of GPs are to be used as a source for deriving indicators in the future, it must be investigated whether the recordings in an EMR as used up to now for daily care are also suitable for deducing indicators. This means that indicators deduced from practitioners’ EMR must be compared to indicators deduced from CDR, in order to assess whether the quality of recording of clinical data in an EMR is equivalent to the quality of recording in a CDR. Because up to now the CDR was used to report to health insurers, we assume that therein the process and outcome of care is recorded more correctly than in the EMR. Moreover, the associated practices received feedback reports on missing data in the CDR and had a direct financial benefit in completing the data. The scarce literature on this topic shows that recording in a CDR is equally or even more accurate than in an EMR.16 Therefore, we assume that the CDR has more ground truth than the practitioners’ EMR and thus can be used as a reference standard. In this paper, we compare these two types of recording systems for the disease type 2 diabetes mellitus in a primary care group in The Netherlands.

Methods

Design

For this study, data were used from 58 general practices connected to a primary care group from a region located in the south-east of The Netherlands. Two sources were used: the EMR of the practices and the CDR of the primary care group. Table 1 provides an overview of the main characteristics of both types of systems.

Table 1.

Characteristics of CDR and EMR

| Characteristics (2011) | CDR | EMR |

|---|---|---|

| Main purpose | Reimbursement | Routine care |

| Data | Data required for reporting quality indicators of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus | All morbidity of all patients in general practice |

| No of databases | One | Several |

| Data model | One | Five (one for each type of EMR) |

| Frequency of data entry | Once per patient per year | On a daily basis |

| Data entry forms | Web-based form; one data entry field per item | Various forms; the same item can be recorded in several fields |

| Data extraction and data processing | Simple | Complex |

| Feedback to general practices | Twice a year on missing data and quality indicators | No routine feedback |

| Reporting | Twice a year benchmark on quality indicators | No routine reports |

CDR, chronic disease registry; EMR, electronic medical record.

In general, the CDR is much simpler than the EMR, which makes it relatively easy to enter, extract, process, analyze, and report the data. It only contains data of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus required for reporting indicators. Data in the CDR are manually entered by staff members throughout the year. They fill out a web-based form with coded questions (no free text) during or after the yearly check-up, that is, data are entered only once per year per patient. This form largely follows the coding systems that are used in the EMR, although in some cases the input format was simplified. For example, the use of medication was entered using a categorical variable, that is, (a) no medication (only lifestyle and/or diet), (b) only oral antidiabetic agents, (c) oral antidiabetic agents and insulin or (d) only insulin. This input format followed the standard diabetes mellitus (SDM)5 of the Dutch College of General Practitioners, which describes exactly how quality indicators should be calculated. In particular, the SDM states that the use of medication has to be calculated as four mutually exclusive categories. When GPs enter (numeric or categorical) data in the CDR, they are derived from various sources including answers of patients (eg, smoking habits), measurements in the practice (eg, blood pressure), letters from other healthcare providers (eg, the previous GP), and the EMR (especially laboratory values).

In contrast, the use of the EMR for assessing quality indicators is complicated. To start with, the practices use five different types of EMR systems, each with their own peculiarities. Data in the EMR are usually entered manually by staff members, except for laboratory values, which are added automatically. In all EMR, complaints and diseases can be recorded using the international classification of primary care,20 prescriptions are coded using the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system,21 and (laboratory) measurements can be recorded using a code table, which is maintained by the Dutch College of General Practitioners. For each EMR, different processes and extraction packages are needed to obtain the data. At our department, the extracted data are mapped into a uniform data model and stored in a data warehouse. Because the EMR contains all medical data of all patients of the practices, thus also of patients without type 2 diabetes, queries were built to match the right group of patients and subsequently the right medical data. For example, the indicator ‘only insulin’ was calculated by querying the medication list for patients with insulin (ATC code A10A) but without oral antidiabetic agents (ATC code A10B). Furthermore, data in the EMR can be recorded in several fields. For instance, smoking can be recorded as free text, as an international classification of primary care code (ie, P17: tobacco abuse) or as a categorical variable (ie, measurement code 1739: 1 ‘yes’, 4 ‘in the past’ or 3 ‘never’). However, according to the SDM, code 1739 must be used to compute the percentage of current smokers.5 All indicators in the SDM are based on coded data (no free text). In this study, we built queries that strictly follow these SDM specifications.

The data from CDR and EMR were extracted over 2011 (although the CDR had a reference date of 27 April 2012), and subsequently matched on the basis of practice numbers in combination with patient numbers, which were unique within practices (but not across practices), resulting in a group of 8235 patients stored into one data file (see supplementary appendix 1, available online, for further information). These were all patients that occurred in both systems. Some patients could not be matched, when this was to be expected: 183 patients from the CDR and 280 patients from the EMR.

This study was performed according to the code of conduct for health research, which has been approved by the data protection authorities for conformity with the applicable Dutch privacy legislation. All GPs gave permission for conducting this study and informed their patients who could object to the use of their data.

Data analysis

The data, obtained on patient level from both systems, were compared for 19 process and outcome indicators described in the SDM,5 see table 2.

Table 2.

Used indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus on the basis of the SDM

| Process indicators | Outcome indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Description | No. | Description |

| 6 | HbA1c test | 10 | Systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg |

| 9 | Systolic blood pressure measurement | 13 | LDL <2.5 mmol/L |

| 15 | Creatinine clearance test | 16 | Creatinine clearance ≥30 and <60 mL/min or mL/min per 1.73 m2 |

| 18 | Urine albumin test | 17 | Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min or mL/min per 1.73 m2 |

| 19 | Smoking status recorded | 22 | BMI <25 kg/m2 |

| 21 | BMI recorded | 27 | No medication, only lifestyle and/or diet |

| 25 | Eye assessment | 28 | Medication: only oral antidiabetic agents |

| 29 | Medication: oral antidiabetic agents and insulin | ||

| 30 | Medication: only insulin | ||

| 34 | Smokers | ||

| 36 | HbA1c <53 mmol/mol | ||

| 37 | HbA1c >69 mmol/mol | ||

The numbers for the indicators that are used in this paper are the same numbers as those used in this SDM.

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SDM, standard diabetes mellitus.

In this standard there is a total of 33 process and outcome indicators; however, in the CDR only 19 of these indicators are used for the following reasons. The CDR was designed in 2007, when not all current indicators were available, or, if they were available, pragmatic reasons played a role, such as the selection of a minimal but representative set of indicators in order to decrease the administrative burden for recording the underlying clinical items. Therefore, we did not compare the other 14 indicators of the SDM (namely 11, 12, 14, 23, 24, 26, 31–33, 35 and 38–41) because the clinical items in the EMR were not, or not similarly, recorded in the CDR.

For process indicators, we examined whether the underlying items were recorded within the reporting period (2011). If there was at least one (valid) value recorded for a patient, an associated process variable was considered as ‘present’. However, when items did not fit some additional criteria (eg, the item was invalid, eg, a blood pressure of 0), as well as in situations in which no items were found for that patient at all, the process variable was considered as ‘absent’.

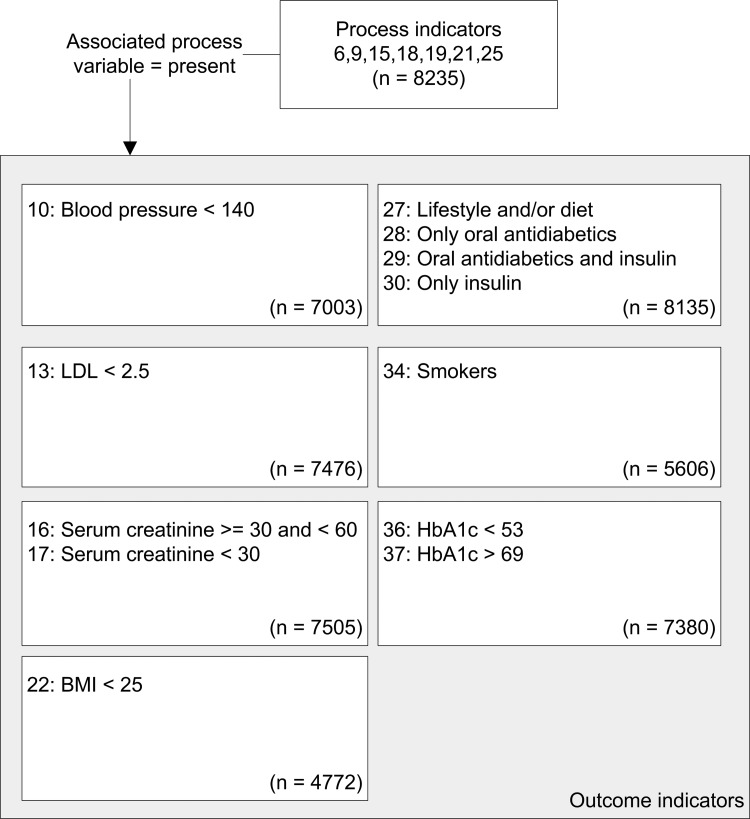

In comparing the process indicators we used all 8235 patients, analyzing the number of ‘present’ values for both systems. If a healthcare activity is not performed, it is not possible to determine the effect of that activity. Therefore, for outcome indicators we only used patients in whom the associated process variable was ‘present’. For example, in analyzing the number of patients in whom the body mass index (BMI) was lower than 25, we only used those patients whose BMI was recorded. Therefore, for each outcome indicator the patient population was smaller than the original group of 8235 patients and varied per indicator (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study population for outcome indicators. BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

For outcome indicators, we analyzed whether the last recorded item within the reporting period (2011) met the criterion of the indicator, for instance ‘is the BMI lower than 25?’. If so, an associated outcome variable was considered as ‘compliant’, in all other cases the variable was considered as ‘non-compliant’.

The distribution of the process and the outcome variables for both systems will be computed via the crosstabs procedure in PASW (V.18). For each indicator, the population size, the number and percentage of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), as well as of false negatives (FN) are computed. True positives are patients who score ‘present’ for a process indicator or ‘compliant’ for an outcome indicator in both systems (see table 3 for an example), while true negatives represent ‘absent’ or ‘non-compliant’ scores. As we are using recordings in the CDR as the reference, false positives are patients who score ‘present’ or ‘compliant’ for an indicator in the EMR, but ‘absent’ or ‘non-compliant’ in the CDR, while false negatives are patients who score ‘absent’ or ‘non-compliant’ for an indicator in the EMR and not in the CDR.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients for indicator ‘HbA1c testing’

| CDR | ||

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c testing | Present | Absent |

| EMR | ||

| Present | 7380 (TP) | 75 (FP) |

| Absent | 715 (FN) | 65 (TN) |

TP, present in both systems; FP, absent in CDR but present in EMR; TN, absent in both systems; FN, present in CDR but absent in EMR.

CDR, chronic disease registry; EMR, electronic medical record; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

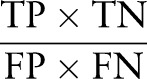

We also report a statistical measure, the diagnostic OR (DOR), a counterpart of the OR, which expresses the general test performance. In our study, the DOR is the ratio of the odds of presence (or compliance) of recordings in the reference standard relative to odds of the presence (or compliance) of recordings in the EMR, and is computed as follows:

|

A value of one indicates that the test (in this case the EMR) cannot discriminate between patients with or without the presence (or compliance) of recordings in the reference standard, and should therefore not be used for this purpose.22 The value of the DOR can be infinitely high, and high values indicate that the test performs very well.22 In our study, a high DOR suggests that, when using one test as a reference standard (in this case the CDR), the other test (in this case the EMR) is accurate in classifying results.22

Using the DOR over the perhaps more familiar Cohen's κ has several advantages. First, the DOR allows comparing test performance to a reference standard, while Cohen's κ is a measure of agreement between two observers. Second, the DOR is insensitive to the prevalence and therefore is a more stable measure than Cohen's κ. Third, Cohen's κ is dependent on the marginal proportions, due to prevalence effects and interobserver bias, while the DOR is not.22–24 While often a low DOR will correspond with a low κ and vice versa, it is unclear how exceptions must be interpreted due to the latter two undesirable effects. Therefore, we choose to report the DOR.23–26

Results

Process indicators

Table 4 shows the results for the process indicators. The indicator with the highest DOR was hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) testing. However, for all process indicators the DOR was less than 20, while a DOR above 20 is recommended for a test to be clinically useful.25 The lowest scoring process indicators were blood pressure measurement, urine albumin test, BMI recorded and eye assessment. For the indicators smoking status recorded, BMI recorded and eye assessment, the proportion of false negatives was augmented, suggesting that these values were more accurately recorded in the CDR than in the EMR.

Table 4.

Process indicators

| Number | Description | N | TP | TP % | FP | FP % | TN | TN % | FN | FN % | DOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | HbA1c testing | 8235 | 7380 | 89.6 | 75 | 0.9 | 65 | 0.8 | 715 | 8.7 | 8.9 |

| 9 | Blood pressure measurement | 8235 | 7003 | 85.0 | 66 | 0.8 | 49 | 0.6 | 1117 | 13.6 | 4.7 |

| 15 | Serum creatinine test | 8235 | 7505 | 91.1 | 117 | 1.4 | 56 | 0.7 | 557 | 6.8 | 6.4 |

| 18 | Urine albumin test | 8235 | 6410 | 77.8 | 550 | 6.7 | 373 | 4.5 | 902 | 11.0 | 4.8 |

| 19 | Smoking status recorded | 8235 | 5606 | 68.1 | 51 | 0.6 | 147 | 1.8 | 2431 | 29.5 | 6.6 |

| 21 | BMI recorded | 8235 | 4772 | 57.9 | 254 | 3.1 | 423 | 5.1 | 2786 | 33.8 | 2.9 |

| 25 | Eye assessment | 8235 | 4826 | 58.6 | 367 | 4.5 | 687 | 8.3 | 2355 | 28.6 | 3.8 |

TP, true positive (present in both systems); FP, false positive (absent in CDR but present in EMR); TN, true negative (absent in both systems); FN, false negative (present in CDR but absent in EMR). BMI, body mass index; CDR, chronic disease registry; DOR, diagnostic OR; EMR, electronic medical record; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Outcome indicators

Table 5 shows the results for the outcome indicators. The indicator with the highest DOR was creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. For this indicator the DOR was very high, meaning that the EMR discriminates very well between patients with creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min or greater and those with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min, according to the reference standard. For most indicators the DOR was over 20, except for systolic blood pressure less than 140 mm Hg, which was also the indicator with the lowest DOR.

Table 5.

Outcome indicators

| Number | Description | N | TP | TP % | FP | FP % | TN | TN % | FN | FN % | DOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | HbA1c <53 mmol/mol | 7380 | 4647 | 63.0 | 342 | 4.6 | 2113 | 28.6 | 278 | 3.8 | 103.3 |

| 37 | HbA1c >69 mmol/mol | 7380 | 178 | 2.4 | 86 | 1.2 | 7024 | 95.2 | 92 | 1.2 | 158.0 |

| 10 | Systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg | 7003 | 3001 | 42.9 | 734 | 10.5 | 2320 | 33.1 | 948 | 13.5 | 10.0 |

| 13 | LDL <2.5 mmol/L | 7476 | 3552 | 47.5 | 261 | 3.5 | 3371 | 45.1 | 292 | 3.9 | 157.1 |

| 16 | Creatinine clearance ≥30 and <60 mL/min or mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 7505 | 1369 | 18.2 | 324 | 4.3 | 5397 | 71.9 | 415 | 5.5 | 54.9 |

| 17 | Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min or mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 7505 | 45 | 0.6 | 22 | 0.3 | 7415 | 98.8 | 23 | 0.3 | 659.4 |

| 34 | Smokers | 5606 | 803 | 14.3 | 102 | 1.8 | 4607 | 82.2 | 94 | 1.7 | 385.8 |

| 22 | BMI <25 kg/m2 | 4772 | 708 | 14.8 | 77 | 1.6 | 3881 | 81.3 | 106 | 2.2 | 336.7 |

| 27 | No medication, only lifestyle and/or diet | 8135 | 1603 | 19.7 | 445 | 5.5 | 5858 | 72.0 | 229 | 2.8 | 92.1 |

| 28 | Medication: only oral antidiabetic agents | 8135 | 4760 | 58.5 | 395 | 4.9 | 2481 | 30.5 | 499 | 6.1 | 59.9 |

| 29 | Medication: oral antidiabetic agents and insulin | 8135 | 547 | 6.7 | 172 | 2.1 | 7145 | 87.8 | 271 | 3.3 | 83.8 |

| 30 | Medication: only insulin | 8135 | 135 | 1.7 | 78 | 1.0 | 7831 | 96.3 | 91 | 1.1 | 148.9 |

TP, true positive (compliant in both systems); FP, false positive (non-compliant in CDR but compliant in EMR); TN, true negative (non-compliant in both systems); FN, false negative (compliant in CDR but non-compliant in EMR). BMI, body mass index; CDR, chronic disease registry; DOR, diagnostic OR; EMR, electronic medical record; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we compared two types of information systems in general practice for generating quality indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indicators from EMR of GPs were compared to a reference standard, that is, indicators from a CDR that was specifically designed for monitoring the course of this disease. The DOR was used to compare indicators from both types of systems. The process indicator with the highest DOR was HbA1c testing (8.9), while the outcome indicator with the highest DOR was creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min (659.4). Generally, the DOR was below 20 for all process indicators, and above 20 (in fact, even above 50) for most outcome indicators. Clearly, there is much less concordance for process indicators than for outcome indicators. Therefore, we conclude that clinical items are not yet recorded adequately enough in the EMR for retrieving indicators, but if they are, the value of the item does not seem to differ too much between both systems, which is in accordance with the results found in Fokkens et al.16

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has several strengths. First of all, this is one of the very few studies,16 in which the concurrent recording in two systems is used to investigate the quality of reporting indicators from an EMR. Second, many practices, and therefore a large number of patients, were included in the analyses. Third, the results of our study may not only be beneficial for reducing the workload of GPs, but they also shed light on the reliability and validity of the data when EMR are used for scientific research on indicators.27

This study also has limitations. We used the CDR as a reference standard, because it was used for reporting to health insurers (ie, on care group level). The results of our study support this choice as for process indicators the percentage of false negatives (ie, only present in the CDR) is much higher than the percentage of false positives (ie, only present in the EMR). However, although the CDR is the best reference standard available, it is not an absolute gold standard. Part of the concordance between both systems can be explained by the fact that some information in the CDR is derived from the EMR, in particular laboratory values. Also, some findings might be explained by differences in the frequency of data entering between CDR and EMR. In particular, the low DOR (10) for systolic blood pressure less than 140 mm Hg might be explained by the fact that blood pressure is measured often (see Struijs et al), 28 which increases the chance that the last recorded blood pressure in the EMR is not the same blood pressure that was recorded in the CDR during or after the yearly check-up. Another limitation is the 3 months difference in extraction period, which may have underestimated the concordance between process indicators.

Implications for GPs

The results of this study imply that an EMR can be used for reporting indicators if GPs will make some adjustments in their recording habits for the EMR, so that recordings are less often missing or if they are already present, they should be stored in the right place (eg, not as free text). We believe that it is desirable and feasible that GPs further improve their recording habits so that an EMR becomes the preferred system for reporting indicators. In this way, GPs can reduce their workload and maintain a good patient overview, especially when more diseases will be funded via primary care groups with an accompanying growing number of CDR.8

An important motivation for GPs to record items underlying indicators meticulously in the EMR is the relation between recording and treatment: Will improving the quality of recording of clinical items improve the quality of care? This question is yet unanswered, as studies show mixed results. Goudswaard et al29 showed that there was no association between completeness of recording and HbA1c levels, suggesting that inadequately recorded patients do not consequently receive a worse treatment. However, in that study 36% of the HbA1c levels that were initially unrecorded exceeded target values.29 Opposing results were found in Fokkens et al,30 in which a CDR was embedded in a structured diabetes care program, and in De Grauw et al,31 in which an improved recording was associated with changes in treatment. More research is needed to answer this question, especially in settings that involve a transfer of treatment.

Implications for policy makers

An important question for policy makers is whether quality indicators from EMR are valid, that is, do they really measure important aspects of the quality of care? There are different studies suggesting that either process or outcome indicators are most important for assessing clinical outcomes.32–39 The results of this study provide more confidence in outcome than in process indicators from EMR. Regarding the validity of the indicators, we noticed that some outcome indicators could be improved. In particular, the indicators with respect to medication (27–30) describe various treatments, but as they are mutually exclusive it remains unclear how these treatments should be interpreted in terms of quality, that is, which indicator reflects the ‘best’ treatment of type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, because treatment with lifestyle and/or diet (no 27) supplements medication treatments (nos 28, 29 and 30) we suggest not to calculate it as a mutually exclusive treatment category.

A possible risk of the use of indicators for funding is that only those treatments will be reimbursed that can be measured by indicators. While chronic care in The Netherlands will be funded as a standard set of care products,9 a predesigned treatment may not fit the needs of individual patients.14 Also, Pollitt et al40 show that once indicators are used for incentives and sanctions, they may start to take on a life of their own. Caregivers may only improve recording habits instead of quality of care, or may apply ‘adverse selection’.41–45 An example of the latter is that hospitals try to attract only the more stable patients (ie, improve their case mix) in reaction to the introduction of a new indicator for diabetes care, the average HbA1c score.46 Therefore, caution is strongly advised when interpreting results of indicators as a direct measure of quality of care and subsequently using them as an incentive.

Implications for medical informaticians

This study is based on data from medical information systems currently used by GPs in The Netherlands, which will certainly differ from systems used in other settings or countries. Nevertheless, part of our research generalizes to other contexts. As for methodological generalizability, the method that we used is expandable to other studies. Whenever quality indicators from two medical information systems are available, and one of the two is a plausible reference standard, the same method can be used to investigate the quality of recordings in the other system. As to the generalizability to other contexts, the results of this study are influenced both by the design of the two systems used and the recording behavior of the general practices. The concurrent use of multiple medical information systems for entering the same data for different purposes occurs in many settings. Contemporary EMR are not designed for generating quality indicators, but for recording care delivered to individual patients often having multiple diseases. Therefore, the underlying data model is complex and the usability of the systems may yet leave much to be desired concerning recording items for indicators. As a CDR is specifically designed to generate indicators, recording the underlying items may be much easier. Nevertheless, we believe that it is unwise to set up a new system for each purpose.

Medical information systems, in particular EMR, are dynamic. They change over time in order to comply with new legislation, new user requirements, new insights, and so on. Integrating all these requirements into one system is difficult. Therefore, it may be tempting in the short term to set up an additional system for new purposes, like the CDR was set up next to the EMR for reimbursement purposes with the advantages of easy data entering, extracting and reporting, and the disadvantage of double recording. However, in the long run, setting up a different system for each purpose leads to inefficiency, fragmentation, and lack of overview. The results of our study regarding process indicators reveal many data inconsistencies between two medical information systems. These inconsistencies are due to various causes including differences between system design, frequency and time of data entering, the fact that double data entry is prone to errors, etc. Data should be recorded only once, for multiple purposes, instead of the other way round. Therefore, the best way to improve recordings of GPs in daily practice is to adapt EMR for ease of recording items for generating quality indicators, for example, by designing single, user-friendly entry screens or by using mandatory fields.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contribution in collecting the data of this study: Waling Tiersma, Hans Peters and the GPs of the primary care group.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Waling Tiersma and Hans Peters.

Contributors: MB, PB and JD designed the study and were responsible for the planning. The primary care group, WdG, Waling Tiersma, Hans Peters and JD collected the data. PB, MB and JD conducted the study. PB performed the statistical analyses, and MB and RA advised on the statistical analyses and helped interpreting the results. PB drafted the manuscript, but all authors were involved in the draft and revisions of the manuscript, and agreed with the final manuscript. PB and MB are the guarantors for this paper.

Ethics approval This study was performed according to the code of conduct for health research, which has been approved by the data protection authorities for conformity with the applicable Dutch privacy legislation.

Patient consent Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Waling Tiersma and Hans Peters

References

- 1.Maarse H, Bartholomée Y. Course and impact of market reform in Dutch health care uncertain. Intereconomics 2008;43:189–94 [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Ven WPMM, Schut FT. Universal mandatory health insurance in the Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Aff 2008;27:771–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenau PV, Lako CJ. An experiment with regulated competition and individual mandates for universal health care: the new Dutch health insurance system. J Health Polit Policy Law 2008;33:1031–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Custers T, Arah OA, Klazinga NS. Is there a business case for quality in The Netherlands? A critical analysis of the recent reforms of the health care system. Health Policy 2007;82:226–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Althuis TR, Bastiaanssen EHC, Bouma M. Overzicht en definitie van diabetesindicatoren huisartsenzorg (Overview and definition of diabetes indicators in primary health care). Utrecht: Dutch College of General Practitioners, 2011:1–31 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ 2003;326:816–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desirable Attributes of a Quality Measure. Rockville: National Quality Measures Clearinghouse, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/tutorial/attributes.aspx (accessed 14 Aug 2012)

- 8.Struijs JN, Baan CA. Integrating care through bundled payments—lessons from the Netherlands. N Engl J Med 2011;364:990–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsiachristas A, Hipple-Walters B, Lemmens KMM, et al. Towards integrated care for chronic conditions: Dutch policy developments to overcome the (financial) barriers. Health Policy 2011;101:122–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schut FT, van de Ven WPMM. Effects of purchaser competition in the Dutch health system: is the glass half full or half empty? Health Econ Policy Law 2011;6:109–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, et al. Integrated care pathways. BMJ 1998;316:133–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oostenbrink JB, Rutten FFH. Cost assessment and price setting of inpatient care in the Netherlands. The DBC case-mix system. Health Care Manag Sci 2006;9:287–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NDF Zorgstandaard. Transparantie en kwaliteit van diabeteszorg voor mensen met diabetes type 2 (NDF Care Standard. Transparency and quality of diabetes care for people with type 2 diabetes) Amersfoort: Nederlandse Diabetes Federatie (Dutch Diabetes Federation), 2007:1–44 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? Arch Pathol Lab Med 1997;121:1145–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Dijk CE, Verheij RA, Swinkels ICS, et al. What part of the total care consumed by type 2 diabetes patients is directly related to diabetes? Implications for disease management programs. Int J Integr Care 2011;11:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fokkens AS, Wiegersma PA, Reijneveld SA. A structured registration program can be validly used for quality assessment in general practice. BMC Health Serv Res, 2009;9:241–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmittdiel J, Bodenheimer T, Solomon NA, et al. Brief report: The prevalence and use of chronic disease registries in physician organizations. A national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:855–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor H, Leitman R, eds. European physicians especially in Sweden, Netherlands and Denmark, lead U.S. in use of electronic medical records. Health Care Res 2002;16:1–3 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hing ES, Burt CW, Woodwell DA. Electronic medical record use by office-based physicians and their practices: United States, 2006. Adv Data Vital Health Stat 2007;393:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamberts H, Wood M. eds International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). Oxford: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. The anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system with defined daily doses (ATC/DDD) http://www.who.int/classifications/atcddd/en/ (accessed 12 Oct 2013)

- 22.Glas AS, Lijmer JG, Prins MH, et al. The diagnostic odds ratio: a single indicator of test performance. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1129–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoehler FK. Bias and prevalence effects on kappa viewed in terms of sensitivity and specificity. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:499–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:423–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer JE, Bachmann LM, Jaeschke R. A readers’ guide to the interpretation of diagnostic test properties: clinical example of sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1043–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki S. Conditional relative odds ratio and comparison of accuracy of diagnostic tests based on 2×2 tables. J Epidemiol 2006;16:145–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Lusignan S, Metsemakers JFM, Houwink P, et al. Routinely collected general practice data: goldmines for research? Inform Prim Care 2006;14:203–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Struijs J, van Til J, Baan C. Experimenting with a bundled payment system for diabetes care in the Netherlands. The first tangible effects Bilthoven: RIVM, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goudswaard AN, Lam K, Stolk RP, et al. Quality of recording of data from patients with type 2 diabetes is not a valid indicator of quality of care. A cross-sectional study. Fam Pract 2003;20:173–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fokkens AS, Wiegersma A, Beltman FW, et al. Structured primary care for type 2 diabetes has positive effects on clinical outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:1083–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Grauw WJC, van Gerwen WHEM, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Outcomes of audit-enhanced monitoring of patients with type 2 diabetes. J Fam Pract 2002;51:459–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sidorenkov G, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, de Zeeuw D, et al. Relation between quality-of-care indicators for diabetes and patient outcomes: a systematic literature review. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:263–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Glickman M, et al. Developing a quality measure for clinical inertia in diabetes care. Health Research and Educational Trust 2005;40:1836–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selby JV, Uratsu CS, Fireman B, et al. Treatment intensification and risk factor control. Toward more clinically relevant quality measures. Med Care 2009;47:395–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sperl-Hillen JM, O'Connor PJ. Factors driving diabetes care improvement in a large medical group: ten years of progress. Am J Manag Care 2005;11(Suppl.):S177–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziemer DC, Miller CD, Rhee MK, et al. Clinical inertia contributes to poor diabetes control in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educ 2005;31:564–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schechtman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1015–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twaddell S. Surrogate outcome markers in research and clinical practice. Australian Prescriber 2009;32:47–50 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz R. Biomarkers and surrogate markers: an FDA perspective. The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics 2004;1:189–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollitt C, Harrison S, Dowswell G, et al. Performance regimes in health care: Institutions, critical junctures and the logic of escalation in England and the Netherlands. Evaluation 2010;16:13–29 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen LA, Woodard LD, Urech T, et al. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Ann Intern Med 2006;145:265–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen Y. Selection incentives in a performance-based contracting system. Health Serv Res 2003;38:535–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roski J, Jeddeloh R, An L, et al. The impact of financial incentives and a patient registry on preventive care quality: increasing provider adherence to evidence-based smoking cessation practice guidelines. Prev Med 2003;36:291–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fairbrother G, Hanson KL, Friedman S, et al. The impact of physician bonuses, enhanced fees, and feedback on childhood immunization coverage rates. Am J Public Health 1999;89:171–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fairbrother G, Siegel MJ, Friedman S, et al. Impact of financial incentives on documented immunization rates in the inner city: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ambul Pediatr 2001;1:206–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bal R, Zuiderent-Jerak T. The practice of markets in Dutch health care: are we drinking from the same glass? Health Econ Policy Law 2011;6:139–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.