Abstract

Majorana fermions are long-sought exotic particles that are their own antiparticles. Here we propose to utilize superconducting circuits to construct two superconducting-qubit arrays where Majorana modes can occur. A so-called Majorana qubit is encoded by using the unpaired Majorana modes, which emerge at the left and right ends of the chain in the Majorana-fermion representation. We also show this Majorana qubit in the spin representation and its advantage, over a single superconducting qubit, regarding quantum coherence. Moreover, we propose to use four superconducting qubits as the smallest system to demonstrate the braiding of Majorana modes and show how the states before and after braiding Majoranas can be discriminated.

Majorana fermions are particles that are their own antiparticles. These long-sought particles have recently received considerable interest (see, e.g., Refs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). It has been recognized12,13,14 that a relatively easy-to-engineer system—one-dimensional (1D) semiconducting wires on an s-wave superconductor—can realize a nontrivial topological state supporting Majorana fermions. This state is characteristic of 1D topological superconductors5, in which Majorana modes can occur without requiring the presence of vortices in the system. The recent experimental observation15 of a zero-bias peak in the differential conductance of a semiconductor nanowire coupled to a superconductor suggested the possible existence of Majorana fermions. Moreover, it was proposed16 to use tunable 1D semiconducting wire networks on an s-wave superconductor to demonstrate the non-Abelian statistics of Majorana fermions, because the Majoranas in the semiconducting wires can also behave like vortices in a p + ip superconductor3,4. In addition, it was also recognized17,18 that when a Jordan-Wigner transformation is performed, a 1D quantum Ising model is equivalent to a 1D topological superconductor, and Majorana modes can also occur therein. Nevertheless, less attention has been paid to this quantum Ising model than to 1D topological superconductors because it was often regarded as a toy model.

In this paper, we propose to realize such a toy model by using experimentally accessible superconducting-qubit arrays. Importantly, superconducting qubits can behave as controllable artificial atoms and tunable interqubit couplings are also achievable (see, e.g., Ref. 19,20,21). For instance, the tunable coupling between flux qubits was experimentally demonstrated in Refs. 22,23,24. For a finite superconducting-qubit array, when the interqubit couplings are tuned to be nonzero and other parameters of the qubits are tuned to be zero, there are two unpaired Majorana modes, which emerge at the left and right ends of the chain in the Majorana-fermion representation. We use these two Majorana modes to encode a qubit which is here called the Majorana qubit. Also, we express this Majorana qubit in the spin representation and show its advantage, over a single superconducting qubit, regarding quantum coherence. Moreover, the advantages of superconducting qubits in controllability make it possible to construct a tunable 1D quantum Ising model on wire networks, similar to the semiconducting wire networks in Ref. 16, to demonstrate the non-Abelian statistics of Majorana modes. We propose to use four superconducting qubits as the smallest circuit to demonstrate the braiding of Majorana modes, and show how the states before and after braiding Majoranas can be discriminated. This should provide an experimentally realizable, relatively simple setup to manipulate and probe Majorana fermions. Thus, our proposal could allow the quantum simulation25 or emulation of Majorana fermions.

Results

Majorana modes in superconducting circuits

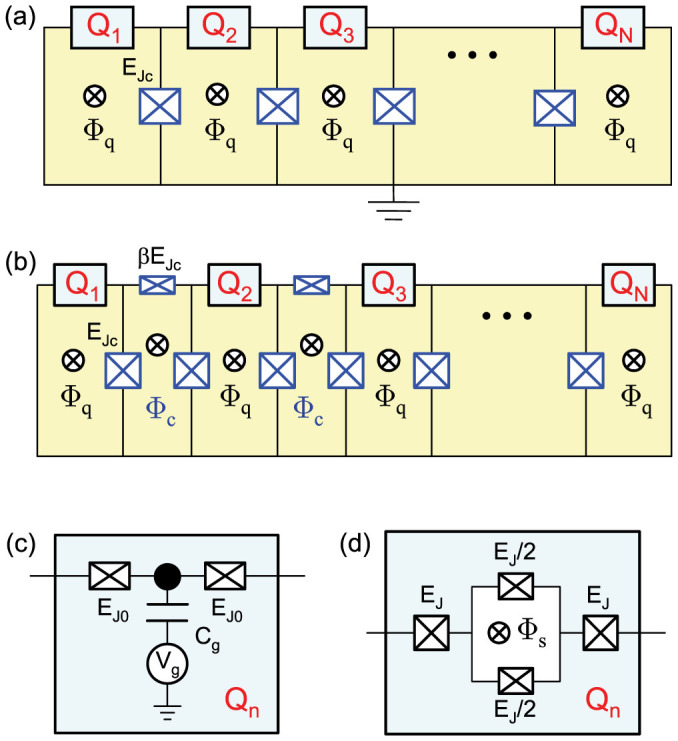

We construct two types of superconducting-qubit arrays (see Figure 1), which can exhibit Majorana modes.

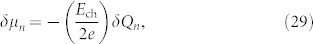

Figure 1. Two arrays of superconducting qubits.

(a) Charge-qubit array: Nearest-neighbor charge qubits Qn and Qn+1 are coupled by a large Josephson junction with coupling energy EJc (shown as a crossed rectangle). (b) Flux-qubit array: Nearest-neighbor flux qubits are coupled by a coupler consisting of a flux-biased loop that is interrupted by two large Josephson junctions (each with coupling energy EJc) and a small Josephson junction with coupling energy βEJc, where  . In (a) and (b), Φq is the flux applied to each qubit loop. (c) Main components of a charge qubit, where a superconducting island (denoted as a solid circle) is connected to two Josephson junctions (each with coupling energy

. In (a) and (b), Φq is the flux applied to each qubit loop. (c) Main components of a charge qubit, where a superconducting island (denoted as a solid circle) is connected to two Josephson junctions (each with coupling energy  and capacitance CJ) and biased by a voltage Vg through a gate capacitance

and capacitance CJ) and biased by a voltage Vg through a gate capacitance  . (d) Main components of a flux qubit, where two Josephson junctions, each with coupling energy

. (d) Main components of a flux qubit, where two Josephson junctions, each with coupling energy  , connects a symmetric dc SQUID biased by a flux Φs.

, connects a symmetric dc SQUID biased by a flux Φs.

(1) Charge-qubit array

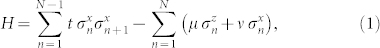

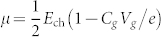

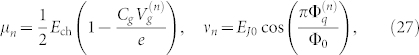

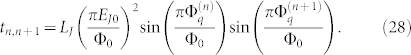

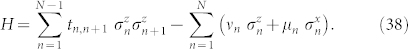

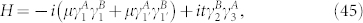

For the array of charge qubits shown in Figure 1(a), every pair of nearest-neighbor qubits are coupled by a large Josephson junction acting as an effective inductance. The non-nearest-neighbor qubits can also be coupled via these large Josephson junctions, but the interactions are negligibly small. Here we assume that all charge qubits are identical and that all large junctions are equal to each other. When leading terms are considered, the Hamiltonian of this charge-qubit array can be written as

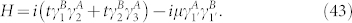

|

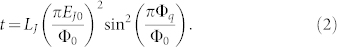

with  , ν = EJ0 cos(πΦq/Φ0), and the interqubit coupling is given by26

, ν = EJ0 cos(πΦq/Φ0), and the interqubit coupling is given by26

|

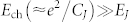

Here  in the charging regime considered here and LJ = Φ0/2πIc, with Ic = 2πEJc/Φ0 and Φ0 being the flux quantum. The eigenstates of the Pauli operator

in the charging regime considered here and LJ = Φ0/2πIc, with Ic = 2πEJc/Φ0 and Φ0 being the flux quantum. The eigenstates of the Pauli operator  are the charge states |0n〉 and |1n〉, corresponding to zero and one extra Cooper pair in the superconducting island of the nth qubit. The Hamiltonian (1) provides an analog to the 1D quantum Ising model.

are the charge states |0n〉 and |1n〉, corresponding to zero and one extra Cooper pair in the superconducting island of the nth qubit. The Hamiltonian (1) provides an analog to the 1D quantum Ising model.

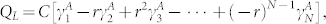

We now consider the case with the fluxes in all charge-qubit loops being tuned to  , so that ν = 0, and the interqubit couplings reach the maximum t = LJ(πEJ0/Φ0)2. Using the Jordan-Wigner transformation17,18:

, so that ν = 0, and the interqubit couplings reach the maximum t = LJ(πEJ0/Φ0)2. Using the Jordan-Wigner transformation17,18:

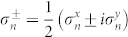

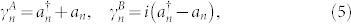

|

where  , one can cast equation (1), in the case of

, one can cast equation (1), in the case of  , to

, to

|

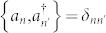

where the Dirac fermions obey the anticommutation relation  . Introducing Majorana fermions:

. Introducing Majorana fermions:

|

one can rewrite the Hamiltonian (4) as

|

where  and

and  . Obviously,

. Obviously,  , which is different from the Dirac fermion.

, which is different from the Dirac fermion.

(2) Flux-qubit array

Figure 1(b) shows an array of flux qubits. Here the small junction in the ordinary flux qubit is replaced by a symmetric dc SQUID to increase the tunability of the qubit. Also, a coupler consisting of three Josephson junctions is used to produce a controllable interqubit coupling between nearest-neighbor flux qubits. We assume that the parameters are the same for all qubits and also for all couplers. Moreover, the plasma frequency of the coupler is much higher than the related qubit energy, so as to keep the coupler in the ground state27. When the leading terms are included, the Hamiltonian of the flux-qubit array can be written as

|

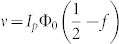

Here  , with Ip being the persistent current of the flux qubit and f = Φq/Φ0 + fs/2, where fs = Φs/Φ0, with Φs being the magnetic flux applied in the SQUID loop [see Figure 1(d)]. The eigenstates of the Pauli operator

, with Ip being the persistent current of the flux qubit and f = Φq/Φ0 + fs/2, where fs = Φs/Φ0, with Φs being the magnetic flux applied in the SQUID loop [see Figure 1(d)]. The eigenstates of the Pauli operator  are the clockwise and anti-clockwise persistent-current states of the nth qubit. The symmetric SQUID provides an effective Josephson junction with coupling energy αEJ, where α = cos(πfs). The exact expression of μ in equation (7) cannot be obtained, but it depends on α; numerical results28 and approximate analytical calculations29 showed that μ = 0 when α = 1. The interqubit coupling strength reads27

are the clockwise and anti-clockwise persistent-current states of the nth qubit. The symmetric SQUID provides an effective Josephson junction with coupling energy αEJ, where α = cos(πfs). The exact expression of μ in equation (7) cannot be obtained, but it depends on α; numerical results28 and approximate analytical calculations29 showed that μ = 0 when α = 1. The interqubit coupling strength reads27

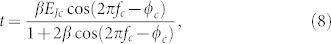

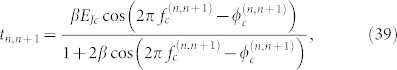

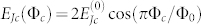

|

where fc = Φc/Φ0 is the reduced flux applied to the coupler, and φc = 2β sin(2πfc)/[1 + 2β cos(2πfc)], with β being the ratio of the Josephson couplings between the smaller and larger junctions in the coupler [see Figure 1(b)].

We study the case with  for all flux qubits, so as to have ν = 0. The Hamiltonian of the system also becomes equation (4) when applying the Jordan-Wigner transformation:

for all flux qubits, so as to have ν = 0. The Hamiltonian of the system also becomes equation (4) when applying the Jordan-Wigner transformation:

|

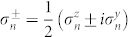

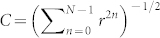

where  . Finally, the Hamiltonian is described by equation (6) when introducing Majorana fermions in equation (5). Therefore, the resulting Hamiltonians in terms of Majorana fermions are the same for both charge- and flux-qubit arrays.

. Finally, the Hamiltonian is described by equation (6) when introducing Majorana fermions in equation (5). Therefore, the resulting Hamiltonians in terms of Majorana fermions are the same for both charge- and flux-qubit arrays.

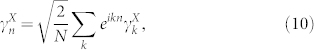

For N → ∞, we can obtain the energy bands of the periodic chain by performing a Fourier transform on Hamiltonian (6):

|

where  and X = A, B. The resulting Hamiltonian in reciprocal space reads

and X = A, B. The resulting Hamiltonian in reciprocal space reads

|

with D(k) = teik + μ. The energy spectrum shows the particle-hole symmetric dispersion

|

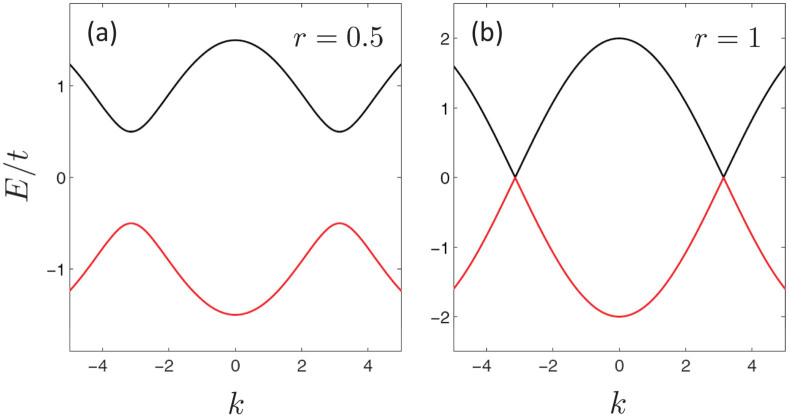

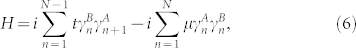

which consists of two bands. As examples, we present in Figure 2 the particle-hole symmetric dispersion for r ≡ μ/t = 0.5 and 1, respectively. It is clear that when r = 1, the gap of the two bands closes at certain values of the wave vector k.

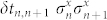

Figure 2. The particle-hole symmetric dispersion.

It is obtained from equation (12), where r ≡ μ/t = (a) 0.5 and (b) 1.

For a finite chain, when |r| < 1, there are two degenerate edge modes with zero energy (i.e., in the middle of the energy gap). These two edge modes can be represented by

|

with the coefficients determined by

|

where n = 1, 2, …, N, and the initial condition is c0 = 0 for the left-end edge state and c2N + 1 = 0 for the right-end edge state. It can be derived that the left- and right-end edge modes are given, respectively, by

|

|

where the normalization factor is  . In Ref. 30, the left- and right-end edge modes were also studied in a flux-qubit array, but the interqubit coupling was not tunable.

. In Ref. 30, the left- and right-end edge modes were also studied in a flux-qubit array, but the interqubit coupling was not tunable.

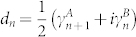

In particular, when μ = 0, the Hamiltonian is reduced to

|

where  is a Dirac fermion composed of two Majoranas at adjoining sites. The edge modes become two unpaired Majorana fermions:

is a Dirac fermion composed of two Majoranas at adjoining sites. The edge modes become two unpaired Majorana fermions:  , and

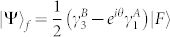

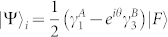

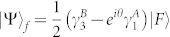

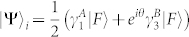

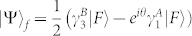

, and  , which emerge at the left and right ends of the chain as local modes in the Majorana-fermion representation. However, as shown in the following subsection, these two Majorana modes become non-local in the spin representation. Moreover, these two degenerate modes do not appear in the Hamiltonian because they have zero energy5,31. Now define |F〉 to be the state in which all eigenstates of the system with E < 0 are occupied and those with E ≥ 0 are empty. When the edge modes are occupied,

, which emerge at the left and right ends of the chain as local modes in the Majorana-fermion representation. However, as shown in the following subsection, these two Majorana modes become non-local in the spin representation. Moreover, these two degenerate modes do not appear in the Hamiltonian because they have zero energy5,31. Now define |F〉 to be the state in which all eigenstates of the system with E < 0 are occupied and those with E ≥ 0 are empty. When the edge modes are occupied,  and

and  are two degenerate ground states of the system. These two Majorana modes can be used to represent the basis states of a qubit called here the Majorana qubit:

are two degenerate ground states of the system. These two Majorana modes can be used to represent the basis states of a qubit called here the Majorana qubit:

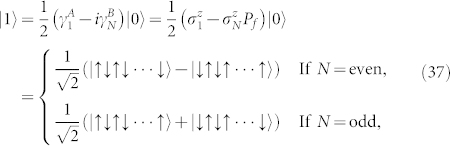

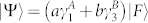

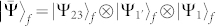

|

where

|

is a non-local Dirac fermion, and dend|0〉 = 0. A similar Majorana qubit was also proposed in quantum wires with spin-orbit interactions (see, e.g., Ref. 16). Such a qubit had initially been thought of as being fully topologically protected, but recent studies showed that it could also suffer from decoherence caused by either coupling to the solid-state environment (see, e.g., Ref. 32) or strong renormalization by interactions (see, e.g., Ref. 33,34,35), which was often neglected.

The Majorana qubit in the spin representation

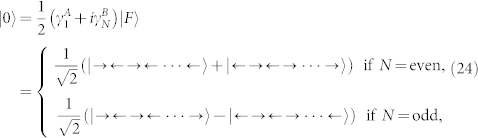

Below we derive the two basis states |0〉 ≡ dend|F〉 and  in the spin representation and discuss issues regarding the quantum coherence of this Majorana qubit.

in the spin representation and discuss issues regarding the quantum coherence of this Majorana qubit.

(1) Charge-qubit array

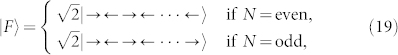

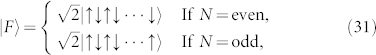

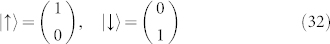

When t > 0 and μ = ν = 0 in equation (1), the state |F〉 can be written, in the spin representation, as

|

where N is the number of charge qubits in the array and

|

are the two eigenstates of σx with eigenvalues 1 and −1, respectively.

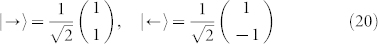

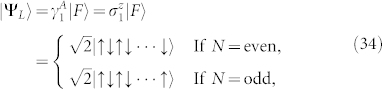

In the spin representation,  and

and  , where the string operator

, where the string operator

|

is the parity operator associated with the Z2 symmetry of the system. Obviously,  becomes a non-local chain operator in the spin representation. The two degenerate ground states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 can be written as

becomes a non-local chain operator in the spin representation. The two degenerate ground states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 can be written as

|

and

|

It is clear that 〈ΨL|ΨR〉 = 0. The two basis states |0〉 ≡ dend|F〉 and  of the Majorana qubit are given, respectively, by

of the Majorana qubit are given, respectively, by

|

and

|

Note that  can also be written as

can also be written as  , which is identical to equation (25). These two basis states of the Majorana qubit are also two degenerate ground states of the system. Moreover, these ground states have well-defined parities because Pc|0〉 = |0〉 and Pc|1〉 = −|1〉 if N = even, and because Pc|0〉 = −|0〉 and Pc|1〉 = |1〉 if N = odd. In Ref. 36, similar Majorana modes in spin-chain networks were also used to encode a qubit.

, which is identical to equation (25). These two basis states of the Majorana qubit are also two degenerate ground states of the system. Moreover, these ground states have well-defined parities because Pc|0〉 = |0〉 and Pc|1〉 = −|1〉 if N = even, and because Pc|0〉 = −|0〉 and Pc|1〉 = |1〉 if N = odd. In Ref. 36, similar Majorana modes in spin-chain networks were also used to encode a qubit.

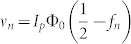

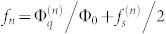

When the externally-tunable parameters such as gate voltages and applied fluxes are identified at each qubit, equation (1) can be rewritten as

|

where

|

and the interqubit coupling is given by

|

As noted in Ref. 17, if  , this longitudinal term will lift the state degeneracy of the system. However, in our designed circuits, this can be avoided because we can have νn = 0 for each qubit by tuning the external flux to

, this longitudinal term will lift the state degeneracy of the system. However, in our designed circuits, this can be avoided because we can have νn = 0 for each qubit by tuning the external flux to  . Also, we can have μn = 0 by tuning the gate voltage to

. Also, we can have μn = 0 by tuning the gate voltage to  , so as to achieve unpaired Majorana modes emerging at the two ends of the charge-qubit array in the Majorana-fermion representation.

, so as to achieve unpaired Majorana modes emerging at the two ends of the charge-qubit array in the Majorana-fermion representation.

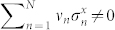

With regard to the quantum coherence of the Majorana qubit, there are three types of local perturbations that we should consider: (i)  , (ii)

, (ii)  , and (iii)

, and (iii)  . The charge perturbation

. The charge perturbation  can be explicitly written as

can be explicitly written as

|

where

|

with the term  arising from the gate-voltage fluctuations and

arising from the gate-voltage fluctuations and  being due to the back-ground charge fluctuations (e.g., the two-level fluctuators). As shown in equations (27) and (28), the parameters νn and tn,n+1 contain both the Josephson coupling EJ0 and the flux

being due to the back-ground charge fluctuations (e.g., the two-level fluctuators). As shown in equations (27) and (28), the parameters νn and tn,n+1 contain both the Josephson coupling EJ0 and the flux  . Therefore, the local perturbations

. Therefore, the local perturbations  and

and  can be contributed by both the critical-current37 and flux fluctuations.

can be contributed by both the critical-current37 and flux fluctuations.

The local perturbation  can only tend to drive the ground state (i.e., the Majorana-qubit state) |0〉 (|1〉) to an excited state, which has an energy level higher than the ground state. This is owing to the protection of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 against the local perturbation

can only tend to drive the ground state (i.e., the Majorana-qubit state) |0〉 (|1〉) to an excited state, which has an energy level higher than the ground state. This is owing to the protection of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 against the local perturbation  , because this perturbation cannot produce a state transition (relaxation) between |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉. Actually, the local perturbation

, because this perturbation cannot produce a state transition (relaxation) between |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉. Actually, the local perturbation  tends to drive |ΨL〉 (|ΨR〉) to an excited state with an energy difference Δ from the ground state, where Δ = 4t for 1 < n < N, and Δ = 2t for n = 1 and N. Nevertheless, such a state transition is not permitted for a small perturbation

tends to drive |ΨL〉 (|ΨR〉) to an excited state with an energy difference Δ from the ground state, where Δ = 4t for 1 < n < N, and Δ = 2t for n = 1 and N. Nevertheless, such a state transition is not permitted for a small perturbation  . Thus, the local perturbation

. Thus, the local perturbation  (i.e., the charge fluctuations) will not produce decoherence to the Majorana qubit. This is a distinct advantage of the Majorana qubit over a single charge qubit in which the charge fluctuations dominate.

(i.e., the charge fluctuations) will not produce decoherence to the Majorana qubit. This is a distinct advantage of the Majorana qubit over a single charge qubit in which the charge fluctuations dominate.

The environmentally-induced decoherence in a near-critical 1D system of  coupled qubits was studied in Ref. 38, where a model Hamiltonian analogous to equation (1) with ν = 0 was used and only the local magnetic-field fluctuations (i.e., the local perturbation

coupled qubits was studied in Ref. 38, where a model Hamiltonian analogous to equation (1) with ν = 0 was used and only the local magnetic-field fluctuations (i.e., the local perturbation  in our model) were considered. It was found that the requirement of preserving the qubits' entanglement over a certain idling time between consecutive gates can be better fulfilled away from criticality, i.e., when r(≡μ/t) ≠ 1. In our study, we consider the case with r = 0, which is away from the criticality, and the two Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉 are entangled states of multiple qubits [see equations (24) and (25)]. Indeed, as discussed above, these multi-qubit entangled states are robust against the local perturbation

in our model) were considered. It was found that the requirement of preserving the qubits' entanglement over a certain idling time between consecutive gates can be better fulfilled away from criticality, i.e., when r(≡μ/t) ≠ 1. In our study, we consider the case with r = 0, which is away from the criticality, and the two Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉 are entangled states of multiple qubits [see equations (24) and (25)]. Indeed, as discussed above, these multi-qubit entangled states are robust against the local perturbation  .

.

As for the local perturbations  and

and  , they should randomly shift the energy levels of the states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉, causing pure dephasing to these Majorana-mode states. However, while

, they should randomly shift the energy levels of the states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉, causing pure dephasing to these Majorana-mode states. However, while  yields pure dephasing to the Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉, the local perturbation

yields pure dephasing to the Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉, the local perturbation  produces relaxation to these Majorana-qubit states. In a circuit composed of inductively-coupled charge qubits, the interqubit coupling is usually much smaller than the Josephson coupling energy EJ0, so the coupler perturbation

produces relaxation to these Majorana-qubit states. In a circuit composed of inductively-coupled charge qubits, the interqubit coupling is usually much smaller than the Josephson coupling energy EJ0, so the coupler perturbation  should be weaker than

should be weaker than  . As shown above, the Majorana qubit is robust again the charge noise. Now, the dominant noise in the Majorana qubit is due to the perturbation

. As shown above, the Majorana qubit is robust again the charge noise. Now, the dominant noise in the Majorana qubit is due to the perturbation  involving both critical-current and flux fluctuations. In order to have a longer decoherence time, a single charge qubit usually works at the optimal (i.e., degeneracy) point Ng ≡ eVg/2e = 1/2. When this single charge qubit is slightly away from the optimal charge degeneracy point, the decoherence time becomes drastically short because of its strong sensitivity to the charge noise. Nevertheless, the Majorana qubit consisting of a charge-qubit array is robust against the charge noise. Then, its quantum coherence is still preserved even if each charge qubit is randomly shifted away from the optimal charge degeneracy point. This is also one of the advantages of the Majorana qubit over a single charge qubit.

involving both critical-current and flux fluctuations. In order to have a longer decoherence time, a single charge qubit usually works at the optimal (i.e., degeneracy) point Ng ≡ eVg/2e = 1/2. When this single charge qubit is slightly away from the optimal charge degeneracy point, the decoherence time becomes drastically short because of its strong sensitivity to the charge noise. Nevertheless, the Majorana qubit consisting of a charge-qubit array is robust against the charge noise. Then, its quantum coherence is still preserved even if each charge qubit is randomly shifted away from the optimal charge degeneracy point. This is also one of the advantages of the Majorana qubit over a single charge qubit.

In Ref. 39, an inhomogeneous spin ladder was proposed to study the robustness of the Majorana modes. This spin model is an inhomogeneous ladder version of the Kitaev honeycomb model40. Similar to the 1D quantum Ising model, the zero-energy Majorana modes of the inhomogeneous spin ladder are also localized in the fermionic representation and emerge at either the two ends of the ladder or the boundary between sections in different topological phases39. As shown above, in the quantum Ising model described by equation (1), the topological ground-state degeneracy is robust against the local perturbation  , but can be lifted by the local perturbation

, but can be lifted by the local perturbation  . In the inhomogeneous spin ladder, the topological ground-state degeneracy cannot be fully lifted by inhomogeneous magnetic fields purely along the x, y or z direction39. This is the advantage of the inhomogeneous spin ladder. However, as further shown in Ref. 39, the topological ground-state degeneracy of the inhomogeneous spin ladder can be lifted by local two-body terms. In the 1D quantum Ising model in equation (1), the two-body (i.e., coupler) perturbation

. In the inhomogeneous spin ladder, the topological ground-state degeneracy cannot be fully lifted by inhomogeneous magnetic fields purely along the x, y or z direction39. This is the advantage of the inhomogeneous spin ladder. However, as further shown in Ref. 39, the topological ground-state degeneracy of the inhomogeneous spin ladder can be lifted by local two-body terms. In the 1D quantum Ising model in equation (1), the two-body (i.e., coupler) perturbation  can also lift the topological ground-state degeneracy, but compared with the local perturbation

can also lift the topological ground-state degeneracy, but compared with the local perturbation  , the local perturbation

, the local perturbation  is much weaker and the coupler perturbation

is much weaker and the coupler perturbation  is even weaker in the 1D quantum Ising model realized using a charge-qubit array.

is even weaker in the 1D quantum Ising model realized using a charge-qubit array.

As a variation of the charge qubit, the transmon qubit was also often used in superconducting quantum circuits41. In this qubit, the perturbation  , which can be due to the fluctuations of flux, cavity photons and critical current, is more important than the perturbation

, which can be due to the fluctuations of flux, cavity photons and critical current, is more important than the perturbation  arising from the charge noise. In the Majorana qubit with charge qubits replaced by transmons, the perturbation

arising from the charge noise. In the Majorana qubit with charge qubits replaced by transmons, the perturbation  becomes more important, but the advantage of the Majorana qubit regarding the insensitivity to the charge noise will still remain. Therefore, the quantum coherence of the Majorana qubit is preserved even if each transmon shifts randomly away from the optimal charge degeneracy point.

becomes more important, but the advantage of the Majorana qubit regarding the insensitivity to the charge noise will still remain. Therefore, the quantum coherence of the Majorana qubit is preserved even if each transmon shifts randomly away from the optimal charge degeneracy point.

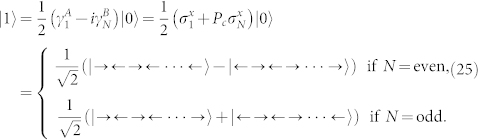

(2) Flux-qubit array

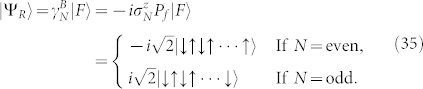

When t > 0 and μ = ν = 0 in equation (7), the state |F〉 can be written, in the spin representation, as

|

where

|

are the two eigenstates of σz with eigenvalues 1 and −1, respectively.

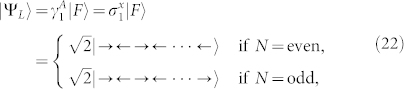

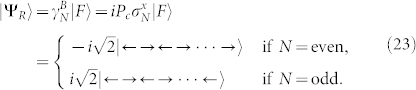

It can be derived that  and

and  , where the parity operator associated with the Z2 symmetry of the system is given by

, where the parity operator associated with the Z2 symmetry of the system is given by

|

In the spin representation, the two degenerate ground states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 can be written as

|

and

|

Also, it is clear that 〈ΨL|ΨR〉 = 0. The two basis states |0〉 ≡ dend|F〉 and  of the Majorana qubit are given, respectively, by

of the Majorana qubit are given, respectively, by

|

and

|

These two basis states of the Majorana qubit are also two degenerate ground states of the system and have well-defined parities.

When the parameters are identified at each qubit, we can rewrite equation (7) as

|

Here  , and

, and  , where

, where  . The interqubit coupling reads

. The interqubit coupling reads

|

where

|

and  is the reduced flux applied to the coupler between qubits n and n + 1.

is the reduced flux applied to the coupler between qubits n and n + 1.

The local perturbation  can only tend to drive the ground state (i.e., the Majorana-qubit state) |0〉 (|1〉) to an excited state of the system which has an energy level higher than the ground state. Similar to the case of the charge-qubit array, this is also owing to the protection of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 against the local perturbation

can only tend to drive the ground state (i.e., the Majorana-qubit state) |0〉 (|1〉) to an excited state of the system which has an energy level higher than the ground state. Similar to the case of the charge-qubit array, this is also owing to the protection of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 against the local perturbation  . Indeed, the local perturbation

. Indeed, the local perturbation  tends to drive |ΨL〉 (|ΨR〉) to an excited state with an energy difference Δ from the ground state, where Δ = 4t for 1 < n < N, and Δ = 2t for n = 1 and N. Nevertheless, such a state transition is not permitted for a small perturbation

tends to drive |ΨL〉 (|ΨR〉) to an excited state with an energy difference Δ from the ground state, where Δ = 4t for 1 < n < N, and Δ = 2t for n = 1 and N. Nevertheless, such a state transition is not permitted for a small perturbation  . Therefore, in contrast to a single flux qubit, the local perturbation

. Therefore, in contrast to a single flux qubit, the local perturbation  will not produce decoherence to the Majorana qubit.

will not produce decoherence to the Majorana qubit.

The local perturbation  randomly shifts the energy levels of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 to cause pure dephasing to these states. Also, it produces relaxation to the Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉. However, the coupler perturbation

randomly shifts the energy levels of the Majorana-mode states |ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉 to cause pure dephasing to these states. Also, it produces relaxation to the Majorana-qubit states |0〉 and |1〉. However, the coupler perturbation  yields pure dephasing to both the Majorana-mode states (|ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉) and the Majorana-qubit states (|0〉 and |1〉). Because the interqubit coupling is usually much smaller than IpΦ0, the coupler perturbation

yields pure dephasing to both the Majorana-mode states (|ΨL〉 and |ΨR〉) and the Majorana-qubit states (|0〉 and |1〉). Because the interqubit coupling is usually much smaller than IpΦ0, the coupler perturbation  should be much weaker than

should be much weaker than  . Therefore, in the case of a flux-qubit array, the dominant noise of the Majorana qubit is due to the perturbation

. Therefore, in the case of a flux-qubit array, the dominant noise of the Majorana qubit is due to the perturbation  . In order to improve the quantum coherence of the Majorana qubit, one can suppress the fluctuations δνn by reducing Ip. This can be achieved by reducing the size of the Josephson junctions in each flux qubit because Ip is proportional to the Josephson coupling energy EJ. Note that when reducing the size of the Josephson junctions to suppress flux noise, the charge noise can finally become important, due to the increasing charging energy. Thus, while the flux noise is suppressed, one can shunt a large capacitance to the Josephson junction, so as to suppress the charge noise as well. This method was proposed to increase the decoherence time of the flux qubit42 and has been implemented in a recent experiment43.

. In order to improve the quantum coherence of the Majorana qubit, one can suppress the fluctuations δνn by reducing Ip. This can be achieved by reducing the size of the Josephson junctions in each flux qubit because Ip is proportional to the Josephson coupling energy EJ. Note that when reducing the size of the Josephson junctions to suppress flux noise, the charge noise can finally become important, due to the increasing charging energy. Thus, while the flux noise is suppressed, one can shunt a large capacitance to the Josephson junction, so as to suppress the charge noise as well. This method was proposed to increase the decoherence time of the flux qubit42 and has been implemented in a recent experiment43.

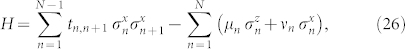

Manipulating and probing Majorana modes

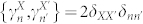

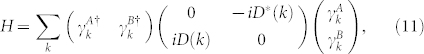

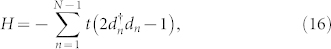

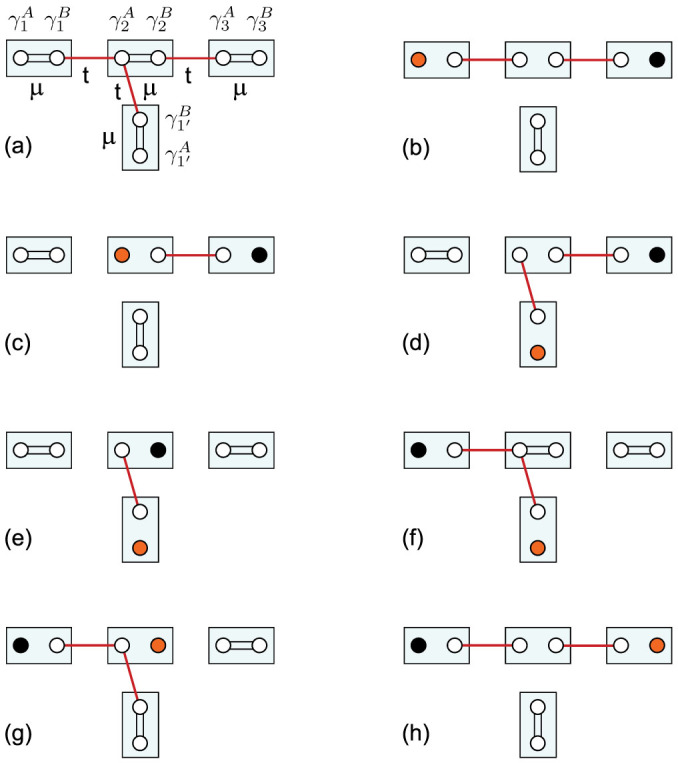

The superconducting-qubit arrays proposed above can be used to realize a tunable 1D quantum Ising model on wire networks, similar to the semiconducting wire networks in Ref. 16, to demonstrate the non-Abelian statistics of Majorana fermions. In particular, braiding Majoranas can be implemented via a T-junction formed by two perpendicular wires16. Here we use four superconducting qubits, as the smallest size of the system, to form such a T-junction [see Figure 3(a)], where ν = 0 for all charge (flux) qubits. When the Jordan-Wigner tranformation is performed, this T-junction of four qubits is described by

|

where qubits are numbered by starting from sites 1 and 1′ and ending at site 3.

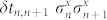

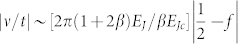

Figure 3. Braiding two unpaired Majorana fermions.

(a) T-junction formed by qubits 1, 2, 3 and 1′, where each qubit is denoted by a rectangular box. Two Majoranas related to the same qubit (e.g.,  and

and  ) can be paired by the parameter μ while two Majoranas related to adjoining qubits (e.g.,

) can be paired by the parameter μ while two Majoranas related to adjoining qubits (e.g.,  and

and  ) can be paired by t. (b) Unpaired-Majorana region for the whole horizontal array, where an unpaired Majorana (denoted by a solid circle) is located at each end. (c) Adiabatically tuning μ to nonzero for qubit 1 and turning off t between qubits 1 and 2 drive the left-end Majorana mode (shown in orange) to the middle qubit. (d) Adiabatically tuning μ to zero for qubit 1′ and turning on t between qubits 2 and 1′ drive the original left-end Majorana to the bottom of the T-junction. (e) The right-end Majorana (in black) is driven to the middle qubit by adiabatically tuning μ to nonzero for qubit 3 and turning off t between qubits 2 and 3. (f) The original right-end Majorana is finally driven to the left end by adiabatically tuning μ to a sufficiently large value for qubit 2, tuning μ to zero for qubit 1 and turning on t between qubits 1 and 2. (g) The Majorana at the bottom is driven to the middle qubit by adiabatically tuning μ to zero for qubit 2 and tuning μ to a sufficiently large value for qubit 1′. (h) Adiabatically turning off t between qubits 2 and 1′, tuning μ to zero for qubit 3, and turning on t between qubits 2 and 3 finally drive the original left-end Majorana to the right end. This accomplishes the anti-clockwise braiding of two Majorana fermions.

) can be paired by t. (b) Unpaired-Majorana region for the whole horizontal array, where an unpaired Majorana (denoted by a solid circle) is located at each end. (c) Adiabatically tuning μ to nonzero for qubit 1 and turning off t between qubits 1 and 2 drive the left-end Majorana mode (shown in orange) to the middle qubit. (d) Adiabatically tuning μ to zero for qubit 1′ and turning on t between qubits 2 and 1′ drive the original left-end Majorana to the bottom of the T-junction. (e) The right-end Majorana (in black) is driven to the middle qubit by adiabatically tuning μ to nonzero for qubit 3 and turning off t between qubits 2 and 3. (f) The original right-end Majorana is finally driven to the left end by adiabatically tuning μ to a sufficiently large value for qubit 2, tuning μ to zero for qubit 1 and turning on t between qubits 1 and 2. (g) The Majorana at the bottom is driven to the middle qubit by adiabatically tuning μ to zero for qubit 2 and tuning μ to a sufficiently large value for qubit 1′. (h) Adiabatically turning off t between qubits 2 and 1′, tuning μ to zero for qubit 3, and turning on t between qubits 2 and 3 finally drive the original left-end Majorana to the right end. This accomplishes the anti-clockwise braiding of two Majorana fermions.

For the Hamiltonian (41), when t = 0 for all pairs of adjoining qubits, the nearest-neighbor Majoranas related to the same site are coupled by μ, and the nearest-neighbor Majoranas related to two adjoining sites are decoupled. Then, Hamiltonian (41) is reduced to

|

In this case, the Majoranas are all paired in the whole T-junction region and no edge states occur. Starting from this phase, we adiabatically vary the parameters of superconducting qubits to have the horizontal array become an unpaired-Majarana region, i.e., adiabatically turn the parameter μ to zero for each qubit in the horizontal array and simultaneously switch on the interqubit coupling t for the horizontal array. Then, the Hamiltonian (42) becomes

|

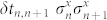

This corresponds to the configuration of Majoranas in Figure 3(b), where a pair of isolated Majoranas emerge at the two ends of the horizontal array. Here adiabatic changes of the parameters with respect to the time τ require that

|

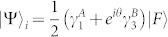

where Eg is the energy gap between the first excited and ground states of the system at the time τ. Generally, the system takes the superposition state of these two degenerate Majorana modes:  , where |F〉 is the state in which all eigenstates of the system with E < 0 are occupied. However, while reaching the state in Figure 3(b), if μ for qubits 1, 2 and 3 are all adiabatically tuned to zero in the same manner and the interqubit coupling between qubits 1 and 2 is adiabatically switched on in the same way as that between qubits 2 and 3, then the left- and right-end Majoranas should occur with equal probabilities. Using this state

, where |F〉 is the state in which all eigenstates of the system with E < 0 are occupied. However, while reaching the state in Figure 3(b), if μ for qubits 1, 2 and 3 are all adiabatically tuned to zero in the same manner and the interqubit coupling between qubits 1 and 2 is adiabatically switched on in the same way as that between qubits 2 and 3, then the left- and right-end Majoranas should occur with equal probabilities. Using this state  as the initial state, one can braid the left- and right-end Majoranas through the steps shown in Figures 3(c)–3(h) by adiabatically tuning the qubit parameters. For instance, by adiabatically switching on μ for qubit 1 and turning off the coupling t between qubits 1 and 2, Hamiltonian (43) is changed to

as the initial state, one can braid the left- and right-end Majoranas through the steps shown in Figures 3(c)–3(h) by adiabatically tuning the qubit parameters. For instance, by adiabatically switching on μ for qubit 1 and turning off the coupling t between qubits 1 and 2, Hamiltonian (43) is changed to

|

i.e., the configuration of Majoranas in Figure 3(b) is adiabatically converted to the configuration of Majoranas in Figure 3(c). Similarly, other steps shown in Figures 3(d)–3(h) can be achieved. This braiding of Majoranas following the steps from Figure 3(b) to 3(h) corresponds to a unitary operator4,16 which transforms  to

to  and

and  to

to  . Therefore, the initial state |Ψ〉i of the system is transferred to

. Therefore, the initial state |Ψ〉i of the system is transferred to  after braiding the left- and right-end Majoranas.

after braiding the left- and right-end Majoranas.

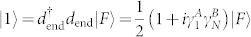

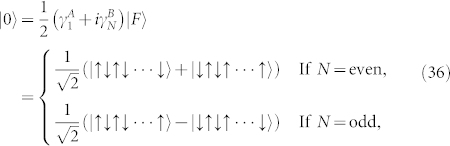

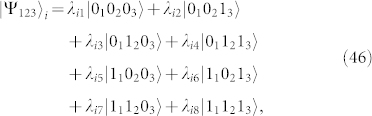

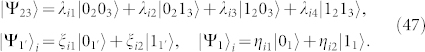

Finally, we focus on probing Majorana fermions. The initial state  given in Figure 3(b) is a ground state of the system with qubit 1′ decoupled from the horizontal array of superconducting qubits. When expressed in the basis states of qubits, this initial state can be written as |Ψ〉i = |Ψ123〉i ⊗ |Ψ1′〉i, where

given in Figure 3(b) is a ground state of the system with qubit 1′ decoupled from the horizontal array of superconducting qubits. When expressed in the basis states of qubits, this initial state can be written as |Ψ〉i = |Ψ123〉i ⊗ |Ψ1′〉i, where

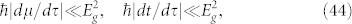

|

and |Ψ1′〉i = ξi1|01′〉 + ξi2|11′〉. Also, the final state  is another degenerate ground state of the same system and can be expressed as |Ψ〉f = |Ψ123〉f ⊗ |Ψ1′〉f, where |Ψ1′〉f = ξf1|01′〉 + ξf2|11′〉, and |Ψ123〉f has the same form as |Ψ123〉i, but the λil are replaced by λfl, with l = 1 to 8. The states |Ψ〉i and |Ψ〉f can be distinguished using experimentally available state-tomography techniques for superconducting qubits (see, e.g., Refs. 44,45), which involve reconstructing an unknown quantum state from a complete set of measurements of the system observables. For the initial state in Figure 3(b) and the final state in Figure 3(h), the qubit 1′ is decoupled from the array consisting of the three coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3. Thus, only one-qubit tomography for qubit 1′ and three-qubit tomography for coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3 are required for distinguishing the initial and final states.

is another degenerate ground state of the same system and can be expressed as |Ψ〉f = |Ψ123〉f ⊗ |Ψ1′〉f, where |Ψ1′〉f = ξf1|01′〉 + ξf2|11′〉, and |Ψ123〉f has the same form as |Ψ123〉i, but the λil are replaced by λfl, with l = 1 to 8. The states |Ψ〉i and |Ψ〉f can be distinguished using experimentally available state-tomography techniques for superconducting qubits (see, e.g., Refs. 44,45), which involve reconstructing an unknown quantum state from a complete set of measurements of the system observables. For the initial state in Figure 3(b) and the final state in Figure 3(h), the qubit 1′ is decoupled from the array consisting of the three coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3. Thus, only one-qubit tomography for qubit 1′ and three-qubit tomography for coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3 are required for distinguishing the initial and final states.

Note that the initial and final states after braiding  and

and  can be written as

can be written as  and

and  , which have different relative phases between

, which have different relative phases between  and

and  . Because the qubit 1′ is decoupled from the horizontal array consisting of the three coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3, the states |Ψ1′〉i and |Ψ1′〉f are the same, in addition to a global phase between them. Thus, when performing quantum-state tomography, the different relative phases between

. Because the qubit 1′ is decoupled from the horizontal array consisting of the three coupled qubits 1, 2 and 3, the states |Ψ1′〉i and |Ψ1′〉f are the same, in addition to a global phase between them. Thus, when performing quantum-state tomography, the different relative phases between  and

and  will give rise to the difference between |Ψ123〉i and |Ψ123〉f.

will give rise to the difference between |Ψ123〉i and |Ψ123〉f.

Experimentally, it is more complicated to use state-tomography techniques to determine the quantum state of three qubits other than two qubits. Therefore, we can consider the state  in Figure 3(c) as the initial state. This state is a ground state of the system with qubits 1′ and 1 decoupled from other qubits and can be decomposed as

in Figure 3(c) as the initial state. This state is a ground state of the system with qubits 1′ and 1 decoupled from other qubits and can be decomposed as  , where

, where

|

From the state in Figure 3(h), further proceeding with one step analogous to that from Figure 3(b) to Figure 3(c), we achieve the final state with the originally unpaired Majoranas  and

and  braided. This final state can also be decomposed as

braided. This final state can also be decomposed as  , where |Ψ1′〉f = ξf1|01′〉 + ξf2|11′〉, |Ψ1〉f = ηf1|01〉 + ηf2|11〉, and |Ψ23〉f has the same form as |Ψ23〉i, but the λil are replaced by λfl, with l = 1 to 4. Similarly, the states

, where |Ψ1′〉f = ξf1|01′〉 + ξf2|11′〉, |Ψ1〉f = ηf1|01〉 + ηf2|11〉, and |Ψ23〉f has the same form as |Ψ23〉i, but the λil are replaced by λfl, with l = 1 to 4. Similarly, the states  and

and  can also be discriminated using state-tomography techniques. Here, because qubits 1 and 1′ are decoupled from the two coupled qubits 2 and 3, only two-qubit tomography for coupled qubits 2 and 3 as well as one-qubit tomography for qubits 1 and 1′ are needed for distinguishing the initial and final states.

can also be discriminated using state-tomography techniques. Here, because qubits 1 and 1′ are decoupled from the two coupled qubits 2 and 3, only two-qubit tomography for coupled qubits 2 and 3 as well as one-qubit tomography for qubits 1 and 1′ are needed for distinguishing the initial and final states.

Experimentally, in addition to one-qubit tomography, two-qubit tomography is also implementable for superconducting qubits (see, e.g., Refs. 44,45). Thus, it is feasible to measure  and

and  because the two-qubit tomography can be used to determine |Ψ23〉i and |Ψ23〉f. Moreover, quantum-state tomography has been performed on three46 or even five47 superconducting qubits, so it also becomes feasible to measure |Ψ〉i and |Ψ〉f by determining |Ψ123〉i and |Ψ123〉f via quantum-state tomography. This is important here since information might be lost by only performing two-qubit tomography, particularly in the case of poor gate fidelity or decoherence.

because the two-qubit tomography can be used to determine |Ψ23〉i and |Ψ23〉f. Moreover, quantum-state tomography has been performed on three46 or even five47 superconducting qubits, so it also becomes feasible to measure |Ψ〉i and |Ψ〉f by determining |Ψ123〉i and |Ψ123〉f via quantum-state tomography. This is important here since information might be lost by only performing two-qubit tomography, particularly in the case of poor gate fidelity or decoherence.

Discussion

When fabricating superconducting circuits, parameter variations unavoidably occur, as in any solid-state system. For the charge-qubit array, ν = 0 can be achieved by having  , irrespective of the parameter variations. Also, μ can be tuned, via the gate voltage Vg, to the required value, even if Ech varies for different qubits. For varying EJ0 among qubits, the interqubit couplings also vary [see equation (2)]. One can replace the large Josephson junction by a dc SQUID and tune the SQUID, i.e., the effective EJc, to obtain the desired value t for the interqubit coupling. For a symmetric SQUID with Josephson coupling energy

, irrespective of the parameter variations. Also, μ can be tuned, via the gate voltage Vg, to the required value, even if Ech varies for different qubits. For varying EJ0 among qubits, the interqubit couplings also vary [see equation (2)]. One can replace the large Josephson junction by a dc SQUID and tune the SQUID, i.e., the effective EJc, to obtain the desired value t for the interqubit coupling. For a symmetric SQUID with Josephson coupling energy  , the effective EJc is given by

, the effective EJc is given by  , where Φc is the magnetic flux in the SQUID loop. In equation (2), EJc is now replaced by EJc(Φc); in both equation (2) and ν, Φq is replaced by

, where Φc is the magnetic flux in the SQUID loop. In equation (2), EJc is now replaced by EJc(Φc); in both equation (2) and ν, Φq is replaced by  . Therefore, the tunability of

. Therefore, the tunability of  with ν = 0 can be implemented by changing both Φc and Φq.

with ν = 0 can be implemented by changing both Φc and Φq.

As for the flux-qubit array, ν = 0 can be achieved by having  . Also, μ can be tuned to the given value by changing the flux fs applied to the SQUID in each qubit. Moreover, even if the parameters of couplers vary, one can tune the flux fc in each coupler to achieve the required value of t for the interqubit coupling [see equation (8)].

. Also, μ can be tuned to the given value by changing the flux fs applied to the SQUID in each qubit. Moreover, even if the parameters of couplers vary, one can tune the flux fc in each coupler to achieve the required value of t for the interqubit coupling [see equation (8)].

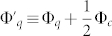

Furthermore, note that even if ν = 0 cannot be experimentally reached very accurately, our proposal still works for the states in the unpaired-Majorana region of the system if  . Experimentally, this can be achieved by designing a relatively strong interqubit coupling for the qubit array. For instance, because Ip ~ 2πEJ/Φ0, one has

. Experimentally, this can be achieved by designing a relatively strong interqubit coupling for the qubit array. For instance, because Ip ~ 2πEJ/Φ0, one has  . When β = 0.1, EJc = 5EJ, and f ∈ [0.499, 0.501],

. When β = 0.1, EJc = 5EJ, and f ∈ [0.499, 0.501],  .

.

In conclusion, we propose superconducting circuits to construct two superconducting-qubit arrays where Majorana modes can occur. The unpaired zero-energy Majorana modes, which emerge at the left and right ends of the chain in the Majorana-fermion representation, can be used to encode a qubit called the Majorana qubit. Also, we express this Majorana qubit in the spin representation and show its advantage, over a single superconducting qubit, for quantum coherence. Moreover, we suggest using four superconducting qubits as the smallest circuit to demonstrate the braiding of Majorana modes, and show how to distinguish the states before and after braiding Majorana modes. These superconducting-qubit arrays can, in principle, be extended to wire networks, similar to the semiconducting wire networks in Ref. 16, to demonstrate the non-Abelian statistics of Majorana modes.

Author Contributions

J.Q.Y. carried out the calculations. Z.D.W., W.Z. and F.N. participated in the discussions. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the work and the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the KITPC for hospitality during the early stage of this work. J.Q.Y. is supported by the NSFC Grant No. 91121015, the MOST 973 Program Grant No. 2014CB921401 and the NSAF Grant No. U1330201. Z.D.W. is supported by the GRF (HKU7045/13P) and the CRF (HKU8/11G) of Hong Kong. F.N. is partially supported by the RIKEN iTHES Project, MURI Center for Dynamic Magneto-Optics, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S).

References

- Wilczek F. Majorana returns. Nat. Phys. 5, 614–618 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Stern A. Non-Abelian states of matter. Nature 464, 187–193 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read N. & Green D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267–10297 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D. A. Non-Abelian statistics of half-quantum vortices in p-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268–271 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaev A. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. Usp 44, 131–136 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. & Kane C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Takahashi Y. & Fujimoto S. Non-Abelian topological order in s-wave superfluids of ultracold fermionic atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 020401 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau J. D., Lutchyn R. M., Tewari S. & Das Sarma S. Generic new platform for topological quantum computation using semiconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 040502 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicea J. Majorana fermions in a tunable semiconductor device. Phys. Rev. B 81, 125318 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Potter A. C. & Lee P. A. Multichannel generalization of Kitaev's Majorana end states and a practical route to realize them in thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 227003 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhmanov A. L., Rozhkov A. V. & Nori F. Majorana fermions in pinned vortices. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075141 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Lutchyn R. M., Sau J. D. & Das Sarma S. Majorana fermions and a topological phase transition in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 077001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oreg Y., Refael G. & von Oppen F. Helical liquids and Majorana bound states in quantum wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 177002 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutchyn R. M., Stanescu T. D. & Das Sarma S. Search for Majorana fermions in multiband semiconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 127001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourik V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicea J., Oreg Y., Refael G., von Oppen F. & Fisher M. P. A. Non-Abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1D wire networks. Nat. Phys. 7, 412–417 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Kitaev A. & Laumann C. Topological phases and quantum computation. arXiv: 0904.2771.

- Lieb E., Schultz T. & Mattis D. Two soluble models of an antiferromagnetic chain. Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 16, 407–466 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- You J. Q. & Nori F. Atomic physics and quantum optics using superconducting circuits. Nature 474, 589–597 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J. Q. & Nori F. Superconducting circuits and quantum information. Phys. Today 58, (No. 11) 42–47 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. & Wilhelm F. K. Superconducting quantum bits. Nature 453, 1031–1042 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg S. H. W. et al. Controllable coupling of superconducting flux qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 057004 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hime H. et al. Solid-state qubits with current-controlled coupling. Science 314, 1427–1429 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen A. O. et al. Quantum coherent tunable coupling of superconducting qubits. Science 316, 723–726 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu I. M., Ashhab S. & Nori F. Quantum Simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–186 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- You J. Q., Tsai J. S. & Nori F. Controllable manipulation and entanglement of macroscopic quantum states in coupled charge qubits. Phys. Rev. B 68, 024510 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Grajcar M., Liu Y. X., Nori F. & Zagoskin A. M. Switchable resonant coupling of flux qubits. Phys. Rev. B 74, 172505 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- You J. Q., Liu Y. X., Sun C. P. & Nori F. Persistent single-photon production by tunable on-chip micromaser with a superconducting quantum circuit. Phys. Rev. B 75, 104516 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg Y. S. et al. Low-frequency characterization of quantum tunneling in flux qubits. Phys. Rev. B 66, 214525 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Levitov L. S., Orlando T. P., Majer J. B. & Mooij J. E. Quantum spin chains and Majorana states in arrays of coupled qubits. arXiv: cond-mat/0108266.

- DeGottardi W., Sen D. & Vishveshwara S. Topological phases, Majorana modes and quench dynamics in a spin ladder system. New J. Phys. 13, 065028 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Budich J. C., Walter S. & Trauzettel B. Failure of protection of Majorana based qubits against decoherence. Phys. Rev. B 85, 121405 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gangadharaiah S., Braunecker B., Simon P. & Loss D. Majorana edge states in interacting one-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 036801 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoudenmire E. M., Alicea J., Starykh O. A. & Fisher M. P. A. Interaction effects in topological superconducting wires supporting Majorana fermions. Phys. Rev. B 84, 014503 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sela E., Altland A. & Rosch A. Majorana fermions in strongly interacting helical liquids. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085114 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tserkovnyak Y. & Loss D. Universal quantum computation with ordered spin-chain networks. Phys. Rev. A 84, 032333 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zaretskey V., Suri B., Novikov S., Wellstood F. C. & Palmer B. S. Spectroscopy of a Cooper-pair box coupled to a two-level system via charge and critical current. Phys. Rev. B 87, 174522 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Khveshchenko D. V. Entanglement and decoherence in near-critical qubit chains. Phys. Rev. B 68, 193307 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Pedrocchi F. L., Chesi S., Gangadharaiah S. & Loss D. Majorana states in inhomogeneous spin ladders. Phys. Rev. B 86, 205412 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Kitaev A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Koch J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- You J. Q., Hu X., Ashhab A. & Nori F. Low-decoherence flux qubit. Phys. Rev. B 75, 140515 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Steffen M. et al. High-coherence hybrid superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 100502 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen M. et al. Measurement of the Entanglement of Two Superconducting Qubits via State Tomography. Science 313, 1423–1425 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipp S. et al. Two-qubit state tomography using a joint dispersive readout. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 200402 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo L. et al. Preparation and measurement of three-qubit entanglement in a superconducting circuit. Nature 467, 574–578 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barends R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500–503 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]