Abstract

Colon cancer (CRC) is a serious health problem through worldwide. Development of novel drug without side effect for this cancer was crucial. Luteolin (LUT), a bioflavonoid has many beneficial effects such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative properties. Azoxymethane (AOM), a derivative of 1, 2-Dimethyl hydrazine (DMH) was used for the induction of CRC in Balb/C mice. CRC was induced by intraperitoneal injection of AOM to mice at the dose of 15 mg/body kg weight for 3 weeks. Mouse was treated with LUT at the dose of 1.2 mg/body kg weight orally until end of the experiment. The expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygense (COX)-2 were analyzed by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. The expressions of iNOS and COX-2 were increased in the case of AOM induction. Administration of LUT effectively reduced the expressions of iNOS and COX-2. The present study revealed that, LUT suppresses both iNOS and COX-2 expressions and act as an anti-inflammatory role against CRC.

Keywords: Azoxymethane, colon cancer, COX-2, iNOS, Luteolin

INTRODUCTION

Colon cancer (CRC), a complex multi-step process involving progressive disruption of homeostatic mechanisms[1] controlling intestinal epithelial proliferation/inflammation, differentiation and programmed cell death, is the third most common malignant neoplasm worldwide.[2] Several epidemiological studies have indicated the influence of lifestyle factors, particularly nutritional factors, on the development of certain forms of cancers, including the colon carcinomas.[3,4] AOM, a metabolite of DMH, has been used extensively to induce CRC in rodents.[5] AOM-induces cancer to both rat and mouse models were the main animal models used to study the effect of dietary agents.[6,7] It is necessary to measure the ability of certain natural product or pharmaceutical agent to hinder the carcinogenesis process.[8]

Luteolin, a 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone, is usually found in a glycosylated form in celery, green pepper, perilla leaf and seed, chamomile tea and Lonicera japonica. Luteolin possesses anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant[9] and phytoestrogen like activities.[10] Several researchers had found that LUT possess anti-neoplastic activities against several human cancers.[11,12,13]

There are two isoforms of cyclooxygenase (COX), namely COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in a number of cell types and tissues and plays a major role in homeostasis. COXs are the rate-limiting enzymes in the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins (PGs). COX-2 catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid into PGH2 and it is further converted into Prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 by prostaglandin synthase and thromboxane synthase respectively. The formation of PGH2 occurs in two steps; initially, two oxygen molecules are incorporated into arachidonate, thus generating PGG2. The synthesis of PGH2 is the second step and it involves reduction of PGG2 catalyzed by the peroxidase activity of COX-2. COX-2 is not detected in most normal tissues but is rapidly induced in response to mitogens, cytokines and tumor promoters, leading to increased accumulation of prostanoids in neoplastic and inflamed tissues.[14] Accumulated evidence suggests that COX-2 selective inhibitors such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) induce apoptosis by suppressing the COX-2.[15]

Varity of natural compounds have the potential to control the neoplasms. Our own observations revealed that Luteolin inhibit CRC in vivo.[16,17,18] Hence, our present investigation focused to study inhibitory effect of LUT against the crucial inflammatory molecules involved in CRC such as iNOS and COX-2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Balb/c mice weighing approximately 25 to 30gm were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Maintenance Unit, Tamilnadu Animal Science and Veterinary University (TANUVAS), Madavaram, India. The animals were acclimatized to the laboratory conditions for a period of two weeks. They were maintained at an ambient temperature of 25 ± 2°C and 12/12h of light-dark cycle and given a standard rat feed (Hindustan Lever Ltd., Bangalore) and water ad libitum. The experiments involved with animals were conducted according to the ethical norms approved by Ministry of Social Justices and Empowerment, Government of India and Institutional Animal Ethics Committee Guidelines.

Experimental procedure

The animals were divided into four groups (n = 6 per group). Group 1 - Control animals received intra peritoneal injections (i.p.) of physiological saline. Group 2 animals were administered with AOM (15mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally (i.p.) once in week for three weeks. Group 3 animals (AOM + LUT) were treated with a single dose with 1.2mg/kg body weight of LUT orally until end of the experiment, after AOM administration as mentioned in group 2.[9] Group 4 received the same dose of LUT alone as mentioned in group 3.

Assay of Alkaline Phosphatase and Lactate Dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase was assayed according to the method described by King (1965a).[19] Alkaline phosphatase was assayed by the method described by King (1965b).[20]

Immunohistochemical analysis of iNOS and COX-2

Immunohistochemical analysis of iNOS and COX-2 were analyzed by the method Ashokkumar and Sudhandiran, (2011).[21] The stained slides were visualized under a light microscope (Nikon XDS-1B). To measure the relative intensity, scoring was done as arbitrary units 4 as intensely stained, 3 as moderately stained, 2 as mild staining, 1 as poorly stained in control and experimental groups.

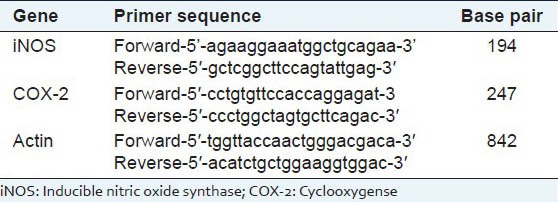

RNA Isolation and PCR analysis

Isolation of RNA and RT-PCR analysis of iNOS and COX-2 were followed by the method Ashokkumar and Sudhandiran, (2011).[21] Total cellular RNA was extracted from colon tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Bangalore Genei, Bangalore, India). cDNA was synthesized from 2μg of total RNA using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Bangalore Genei, India). The cDNA for iNOS, COX-2 and actin were amplified by PCR with gene specific primers [Table 1]. PCR products were analyzed in an agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Table 1.

Primer sequence of iNOS and COX-2

Statistical analysis

All the data were statistically evaluated with SPSS/10.0 software. Hypothesis testing methods included one-way analysis of variance followed by least significant difference (LSD) test *P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All the results were expressed as mean ± S.D.

RESULTS

Luteolin reduces the levels of Alkaline phosphatase and Lactate Dehydrogenase

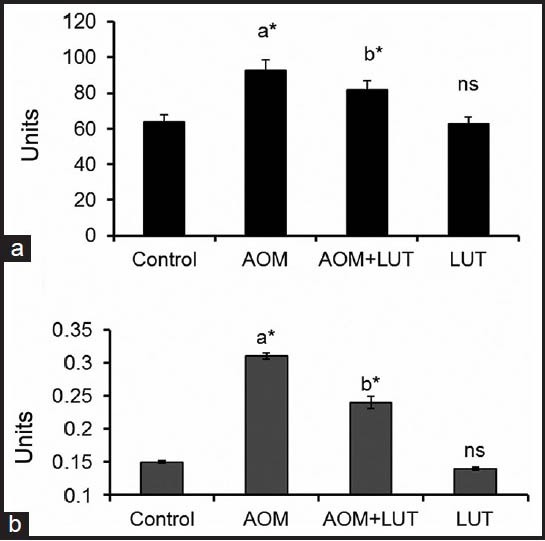

ALP is a non-specific phosphomonoester hydrolase that catalyses the hydrolysis of wide variety of organic monophosphatases and it is a useful marker for the determination of differentiation in colon cancer cells. LDH is recognized as a potential tumor marker enzyme in assessing the proliferation of malignant cells. The possible reason for elevated levels of LDH may be due to higher glycolysis in cancerous conditions, which is the only energy producing pathway for the uncontrolled proliferating malignant cells. Figure 1 shows the levels of ALP and LDH in control and experimental groups of mice. Administration of AOM (Group 2) facilitates the increase in the levels of ALP and LDH. LUT (group 3) treatment substantially reduced the levels of ALP and LDH. In control (Group 1) and LUT (Group 4) state no such alteration in the levels of ALP and LDH enzyme were observed.

Figure 1.

Luteolin reduced the levels of ALP and LDH Units: (A): Activity of ALP (mU/mg protein), (B): activity of LDH (μM of pyruvate liberated/min/mg protein). Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. for 6 mice in each group. aControl Vs AOM, bAOM Vs AOM+LUT, ns-non significant P <0.05

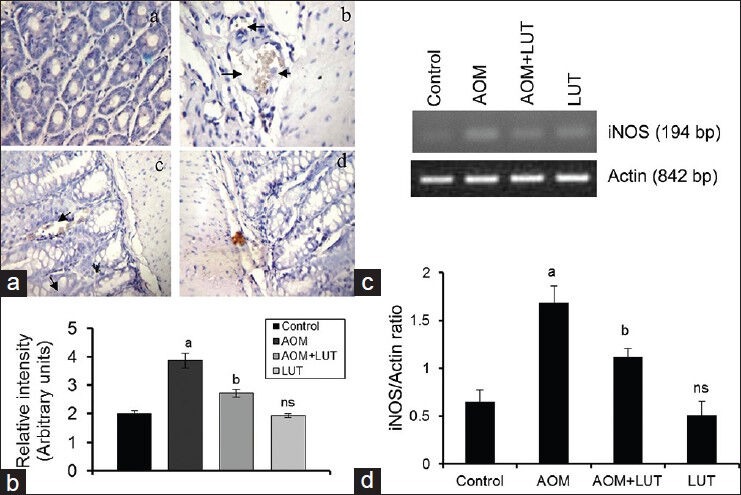

Luteolin decreased the expression of iNOS

Figure 2a shows expression of iNOS in colon tissue. Colon tissue section from control (a) and drug control (d) mouse showed a small level of immunostaining for iNOS. AOM produced an increased expression of iNOS in colon tissues, as shown in (b). The LUT treatment reduced the AOM-induced expression of this iNOS (c). The immunohistochemical staining of iNOS was quantified and the result of the same is represented in Figure 2b. Similar results were observed in RT-PCR analysis of iNOS [Figure 2c]. The imageJ analysis of PCR bands were quantified and illustrated in Figure 2d.

Figure 2.

Luteolin decreases the expression of iNOS (a): (Control) Normal expression of iNOS, (b): (AOM) high expression of iNOS (brown color) was observed, (c): (AOM+LUT) lesser degree of expression of iNOS was noticed, (d): (LUT) Expression was similar to that of control. -> shows the expression of iNOS. (2B), Quantification of the expressions of iNOS. Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. Comparisons: aControl Vs AOM, bAOM Vs AOM+LUT, ns-non significant *P < 0.05. (2C): RT-PCR analysis of iNOS. The band was detected at the 194 bp and Actin was at 842 bp. The quantification of iNOS was normalized with Actin shown in 2D

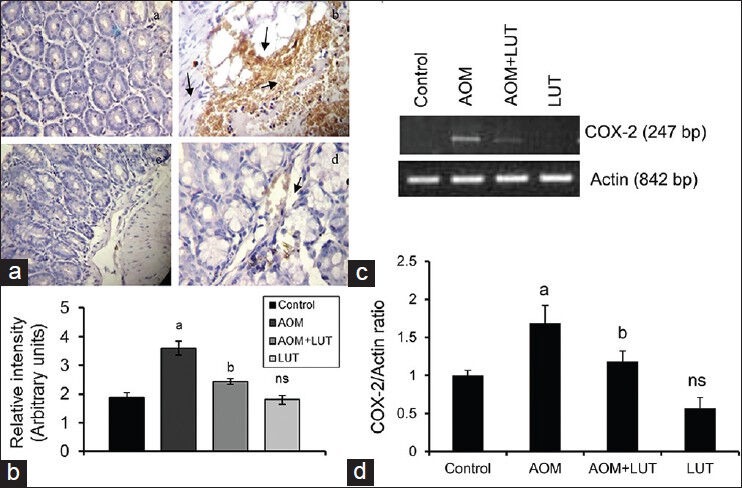

Luteolin decreased the expression of COX-2

An elevated level of COX-2 has been reported in CRC and selective inhibitors of COX-2 could greatly reduce the tumor burden. Control mouse colon tissue section showed a small degree of immunostaining for COX-2 [Figure 3a]. AOM induction increased the levels of COX-2 protein in the colon tissues, as evident from intense and wide spread brown staining in colon tissues (b). However treatment with LUT significantly reduced the expression of COX-2 (c), when compared to AOM induced group. The immunohistochemical staining of COX-2 was quantified and the result of the same is represented in Figure 3b. Similar results were observed in RT-PCR analysis of COX-2 [Figure 3c]. The ImageJ software analysis of PCR bands were quantified and illustrated in Figure 3d. The results of this study exhibited that LUT could reduce the expressions of these inflammatory markers during CRC.

Figure 3.

Luteolin decreases the expression of COX-2 (a): (Control) Normal expression of COX-2, (b): (AOM) high expression of COX-2 (brown color) was observed, (c): (AOM+LUT) lesser degree of expression of COX-2 was noticed, (d): (LUT) Expression was similar to that of control. -> indicates the expression of COX-2 protein. (3B): Quantification of the expression of COX-2. Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. Comparisons: aControl Vs AOM, bAOM Vs AOM+LUT, ns-non significant *P < 0.05. (2C): RT-PCR analysis of COX-2. The band was detected at the 247 bp and Actin was at 842 bp. The quantification of COX-2 was normalized with Actin shown in 3D

DISCUSSION

Flavonoids constitute the largest and most important group of polyphenolic compounds in plants. They are widely distributed in many frequently consumed beverages and food products of plant origin such as fruit, vegetables, wine, tea and cocoa.[22,23] Intake of beverages or food products containing flavonoids has been frequently associated with a reduced risk for developing various cancers.[22,24]

Several studies showed increased expression and activity of iNOS in human colon adenomas.[25,26,27] In the present investigation, the expression of iNOS was increased in AOM-induced mice. The expression of iNOS and nitrotyrosine accumulation (marker of peroxynitrite, the product of NO and superoxide) in inflamed mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis and gastritis demonstrate the production of NO and its potential involvement in the pathogenesis of these diseases.[28] Studies in experimental models of CRC indicate that AOM-induced colon tumors have higher expression and/or activity of iNOS compared to levels found in adjacent colonic tissue.[29,30] But, LUT have a strong ability to suppress iNOS and indirectly prevent the production of NO in disease conditions,[31,32,33] which was concordant with our present study.

The role of COX-2 as an enhancer of carcinogenesis in many organs including the colon is receiving increasing attention. Hence, assays of COX-2 expression may be used to monitor the process of carcinogenesis, and the suppression of COX-2 expression has become an important target for treatment and prevention of CRC.[34,35,36] COX-2 is induced by inflammatory cells, by various stimuli including cytokines, growth factors and tumor inducing factors. Overexpression of COX-2 results in dedifferentiation, adhesion to extra-cellular matrices and inhibition of programmed cell death in untransformed rat intestinal epithelial cells.[37] Inducibility of COX-2 in response to mitogenic stimuli, oncogenes and tumor promoters link it to cell proliferation.[38] Increased COX-2 expression leads to the elevated levels of PGE2, that is correlated with increased MDA, which forms an adduct with DNA in human colon leads to carcinogenesis[39] or inhibit apoptosis in epithelial tumor cells.[40] In the present study, the expression of COX-2 protein in colon tumors was higher than that of normal colonic mucosa. Abundant evidences supports, the role of COX-2 is involved in CRC[37,41,42] and provides the basis for the development of COX-2 selective inhibitors for CRC prevention and treatment.[43] Many reports stating that, LUT selectively inhibits COX-2 in various disease conditions.[33,44] Administration of LUT directly suppresses the expression of COX-2 and thereby reduced the inflammation in colon. Recently we reported that LUT modulates the status of ATPases in AOM-induced CRC[45] and inhibits wnt/β-catenin signaling in vitro.[46]

Our own observations indicated that the LUT, potentially inhibit CRC in rodents. The results obtained from the above findings clearly indicated that, Luteolin inhibits the expression both iNOS and COX-2 in AOM-induced colon carcinogenesis. These two proteins are important mediator of inflammation associated cancer. Hence, LUT act as a novel chemotherapeutic agent to treat CRC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We sincerely thank Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India for funding this project.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pandurangan AK. Potential targets for the prevention of colorectal cancer: A focus on PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Wnt pathways. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2201–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shike M, Winawer SJ, Greenwald PH, Bloch A, Hill MJ, Swaroop SV. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer: WHO collaborating center for prevention of colorectal cancer. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:377–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Heath CW., Jr Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;1325:1593–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112053252301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannucci E, Egan KM, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, et al. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:609–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509073331001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macejová D, Brtko J. Chemically induced carcinogenesis: A comparison of 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea, 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene, diethylnitrosoamine and azoxymethane models. Endocr Regul. 2001;35:53–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy BS. Studies with the azoxymethane-rat preclinical model for assessing colon tumor development and chemoprevention. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:26–35. doi: 10.1002/em.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corpet DE, Pierre F. Point: From animal models to prevention of colon cancer. Systematic review of chemoprevention in min mice and choice of the model system. Cancer Epidemol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:391–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsao AS, Kim ES, Hong WK. Chemoprevention of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:150–80. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashokkumar P, Sudhandiran G. Protective role of Luteolin on the status of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defense against Azoxymethane-induced experimental colon carcinogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:590–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dall’Acqua S, Innocenti G. Antioxidant compounds from Chaerophyllum hirsutum extracts. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:592–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettit GR, Hoard MS, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Petit RK, Tackett LP, et al. Antineoplastic agents 338. The cancer cell growth inhibitory constituents of Terminalia Arjuna (Combretaceae) J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;53:57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Post JF, Varma RS. Growth inhibitory effects of bioflavonoids and related compounds on human leukemic CEM-C1 and CEM-C7 cells. Cancer Lett. 1992;24:207–13. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90145-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin F, Giuliano AE, Van Herle AJ. Growth inhibitory effects of flavonoids in human thyroid cancer cell lines. Thyroid. 1999;19:369–76. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subbaramiah K, Telang N, Ramonetti JT, Araki R, DeVito B, Weksler BB, et al. Transcription of cyclooxygenase-2 is enhanced in transformed mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4424–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang DS, Shen KZ, Wei JF, Liang TB, Zheng SS, Xie HY. Specific COX-2 inhibitor NS398 induces apoptosis in human liver cancer cell line HepG2 through BCL-2. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:204–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandurangan AK, Dharmalingam P, Anandasadagopan AK, Sudhandiran G. Effect of Luteolin on the levels of glycoproteins duringAzoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in mice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1569–73. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandurangan AK, Ganapasam S. Luteolin modulates cellular thiols on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis. Asian J Exp Biol Sci. 2013;4:245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandurangan AK, Ganapsam S. Luteolin induces apoptosis in azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis through the involvement of Bcl-2, Bax, and Caspase-3. J Chem Pharm Res. 2013;5:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.King J. The hydrolases-acid and alkaline phosphatases. In: Van D, editor. Practical Clinical Enzymology. London: Nostrand Co; 1965a. pp. 99–208. [Google Scholar]

- 20.King J. The dehydrogenase of oxido-reductase-lactate dehydrogenase. In: Van D, editor. Practical Clinical Enzymology. London: Nostrand; 1965b. pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashokkumar P, Sudhandiran G. Luteolin inhibits cell proliferation during Azoxymethane-induced experimental colon carcinogenesis via Wnt/?-catenin pathway. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:273–84. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross JA, Kasum CM. Dietary flavonoids: Bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:19–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beecher GR. Overview of dietary flavonoids: Nomenclature, occurrence and intake. J Nutr. 2003;133:3248–54. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3248S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knekt P, Kumpulainen J, Jarvinen R, Rissanen H, Heliovaara M, Reunanen A, et al. Flavonoid intake and risk of chronic diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:560–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambs S, Merriam WG, Bennett WP, Felley-Bosco E, Oqunfusika MO, Oser SM, et al. Frequent nitric oxide synthase-2 expression in human colon adenomas: Implication for tumor angiogenesis and colon cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:334–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lala PK, Chekraborty C. Role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Lancet Oncol. 2001;3:149–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cianchi F, Cortesini C, Fantappiè O, Messerini L, Schiavone N, Vannacci A, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human colorectal cancer: Correlation with tumor angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:793–801. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63876-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleton SJ, Shorthouse MJ, Hunter JO. Increased nitric oxide synthesis in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1993;341:465–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi M, Fukuda K, Ohata T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Increased expression of inducible and endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthases in rat colon tumors induced by azoxymethane. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao CV, Kawamori T, Hamid R, Simi B, Gambrell B, Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of aberrant crypt foci by inducible nitric oxide synthase-selective inhibitors: A safer colon cancer chemopreventive strategy. Carcinogenesis. 1998;20:641–4. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comalada M, Ballester I, Bailón E, Sierra S, Xaus J, Galvez J, et al. Inhibition of pro-inflammatory markers in primary bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages by naturally occurring flavonoids: Analysis of the structure-activity relationship. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1010–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutiérrez-Venegas G, Kawasaki-Cárdenas P, Arroyo-Cruz SR, Maldonado-Frías S. Luteolin inhibits lipopolysaccharide actions on human gingival fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;541:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CY, Peng WH, Tsai KD, Hsu SL. Luteolin suppresses inflammation associated gene expression by blocking NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation pathway in mouse alveolar macrophages. Life Sci. 2007;81:1602–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma RA, Gescher A, Plastaras JP. Cyclooxygenase-2, malondialdehyde and pyrimidopurinone adducts of deoxyguanosine in human colon cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1557–60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, Shimizu M, Kohno H, Yoshitani S, Tsukio Y, Murakami A, et al. Chemoprevention of azoxymethane-induced rat aberrant crypt foci by dietary zerumbone isolated from Zingiber zerumbet. Life Sci. 2001;69:1935–45. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turini ME, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2:A therapeutic target. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:35–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsujii M, DuBois RN. Alteration in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell. 1995;83:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh J, Hamid R, Reddy BS. Dietary fat and colon cancer: Modulation of cyclooxygenase-2 by types and amount of dietary fat during the post initiation stage of colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3465–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanif R, Pittas A, Feng Y, Koutsos MI, Qiao L, Staiano-Coico L, et al. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on proliferation and on induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells by a prostaglandin-independent pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:237–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, Beauchamp RD, DuBois RN. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taketo MM. Cycloxygense-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis (part I) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.20.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao CV, Reddy BS. NASIDs and chemoprevention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:29–43. doi: 10.2174/1568009043481632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy BS, Hirose Y, Lubet R, Steele V, Kelloff G, Paulson S, et al. Chemoprevention of colon cancer by specific cycloxygenase-2 inhibitor, celeoxib, administrated during different stages of carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziyan L, Yongmei Z, Nan Z, Ning T, Baolin L. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin in experimental animal models. Planta Med. 2007;73:221–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandurangan AK, Dharmalingam P, Anandasadagopan SK, Ganapasam S. Inhibitory effect of Luteolin on the status of membrane bound ATPases against Azoxymethane-induced colorectal cancer. J Chem Pharm Res. 2013;5:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandurangan AK, Dharmalingam P, Ananda Sadagopan SK, Ramar M, Munusamy A, Ganapasam S. Luteolin induces growth arrest in colon cancer cells via Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediated through GSK-3β. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2013;32:10. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2013007522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]