Abstract

We present a case of clinically relevant and probable interaction between warfarin and scuppernongs in a 73-year-old woman where ingestion of scuppernongs, a variety of quercetin-containing muscadine grapes, over a period of 2 months was associated with elevations in the International Normalised Ratio to supratherapeutic levels. While muscadine grapes and specifically scuppernongs are found primarily in Southeastern USA, the flavonoid in questionand quercetin is found worldwide as a dietary supplement.

Background

This case highlights a probable drug interaction between warfarin and scuppernongs, a muscadine grape. The muscadine grape family contains large quantities of flavonoids, including quercetin, suggesting the possibility of a flavonoid-induced drug interaction with warfarin. This interaction may have implications for other patients consuming muscadine grapes and even those taking quercetin supplements.

Case presentation

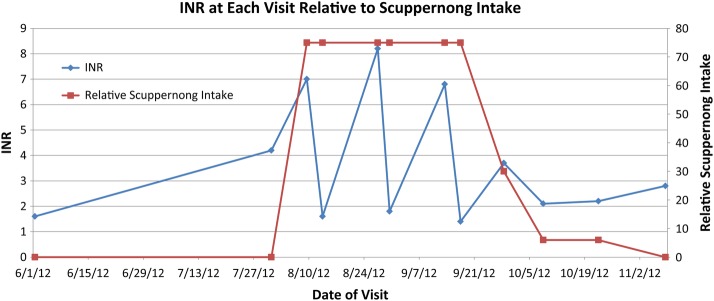

A 73-year-old woman presented to an academic institution's pharmacist-run anticoagulation clinic with a supratherapeutic International Normalised Ratio (INR) of 7.0 (target range 2–3). Her medical history included systolic and diastolic heart failure, pulmonary and cutaneous sarcoidosis, chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis. At this visit, the patient reported taking warfarin 10 mg on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and 12 mg on all other days with no clear reason identified for the supratherapeutic INR on the day of the appointment. During the months prior, the patient had multiple subtherapeutic INRs at doses ranging from 61 to 74 mg weekly. The patient was instructed to take no warfarin on 9, 10 and 11 August and 10 mg on 12 August. Her INR on 13 August declined to 1.6 and she was instructed to decrease her weekly dose by 18%. At the follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she presented with another elevated INR (8.2). A thorough patient history addressing changes in her diet, health and medications was obtained. The patient shared that she had been consuming approximately 75 scuppernongs on a daily basis since the beginning of August. After with-holding warfarin for 3 days, the patient's INR decreased to 1.8 and her weekly warfarin dose was reduced by another 14%. The patient was advised to stop or significantly decrease her consumption of scuppernongs. On her next visit 14 days later, the patient was again found to have a supratherapeutic INR (6.8) and explained that she had continued to eat large daily quantities of scuppernongs. Once again, the patient was instructed to with-hold warfarin for 3 days which resulted in a subtherapeutic INR (1.4). At this visit, the patient explained that scuppernongs were her favourite food and she was unwilling to completely stop consumption. However, she agreed to begin decreasing her daily scuppernong intake. On re-check 2 weeks later, her INR was supratherapeutic but only elevated to 3.7 and she reported a significant reduction in her scuppernong intake from approximately 75 to 30 daily. Her weekly warfarin dose was decreased by another 12%, to a final daily dose of 6 mg. The patient was again educated to reduce her daily scuppernong consumption. Two weeks later, the patient presented with her first therapeutic INR (2.1) since the beginning of the fruit's season and stated she had markedly decreased her scuppernong intake to six daily. Table 1 provides a record of the patient's anticoagulation visits and figure 1 displays the INR trend in relation to reported scuppernong intake.

Table 1.

International Normalised Ratios (INR), action taken, and reported scuppernong intake at each anticoagulation clinic visit

| Clinic visit date | 1 June 2012 | 31 July 2012 | 9 August 2012 | 13 August 2012 | 27 August 2012 | 30 August 2012 | 13 September 2012 | 17 September 2012 | 28 September 2012 | 8 October 2012 | 22 October 2012 | 8 November 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INR | 1.6 | 4.2 | 7 | 1.6 | 8.2 | 1.8 | 6.8 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Action taken at visit | Increase dose to 12 mg daily, except 10 mg Monday, Wednesday and Friday | No warfarin for 1 day, then 12 mg daily, except 10 mg Monday, Wednesday and Friday | No warfarin for 3 days, then 10 mg on day 4 | Take 9 mg daily, except 12 mg every Monday | No warfarin for 3 days | Take 9 mg daily, except 6 mg every Tuesday and Friday | No warfarin for 3 days, then 6 mg on day 4 | Take 6 mg daily, except 9 mg every Monday and Friday | Take 6 mg daily | Continue 6 mg daily | Continue 6 mg daily | Continue 6 mg daily |

| Patient endorses scuppernongs ingested week prior to visit? | No | Likely | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited | Limited | No |

| Relative patient-reported daily quantity of scuppernongs | 0 | Unknown | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 30 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

Figure 1.

International Normalised Ratios (INRs) relative to scuppernong intake.

Outcome and follow-up

During the following 2 weeks, her INR remained therapeutic as she continued to eat minimal to no scuppernongs. Since discontinuation of scuppernong consumption, the patient has had no supratherapeutic INR values.

Discussion

Warfarin is a widely used oral anticoagulant that requires close monitoring and has the potential to interact with flavonoid-containing foods and juices such as cranberry juice.1 However, there are no available case reports regarding warfarin and flavonoid-containing muscadine grapes.

Scuppernongs, a bronze variety of muscadine grapes, are readily available throughout Southeastern USA from August to October, which also coincides with the patient's supratherapeutic INRs reported in this case.2 These grapes are commonly made into different recipes, wines and juices, and are considered a health food by many consumers, primarily due to the flavonoid and antioxidant content.3 The major flavonoid components of muscadine grapes are quercetin, ellagic acid and reservatrol.1 The seeds, skin and pulp of the muscadine grapes contain high concentration of quercetin.2 Our patient explained that she does not eat the skin, but consumes the pulp and seeds indicating a potentially significant amount of quercetin. Quercetin is marketed worldwide as a dietary supplement, antioxidant and nutraceutical to help prevent cancer, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease and even the effects of ageing.4 The proposed mechanism of action of quercetin is by inhibiting oxidative haemolysis.5

Literature suggests that quercetin displaces warfarin from human serum albumin binding sites; specifically there is an overlap of warfarin and quercetin at adjacent albumin binding sites. This creates competitive inhibition that has the ability to displace warfarin and potentially result in higher concentrations of free warfarin in the blood.6 Scuppernongs contain other flavonoids and therefore other mechanisms of interactions such as cytochrome P450 (CYP450), organic anion transport, or absorption interference interactions cannot be ruled out. In fact, flavonoids have been shown in vitro to inhibit CYP450 either by competitively interacting with the substrate binding site of CYP2C9 accessed by flurbiprofen or by non-competitively binding beside Phe100, which is similar to the reported allosteric binding site of warfarin.7

This case illustrates a likely and clinically relevant interaction between scuppernongs, a quercetin-containing muscadine grape, and warfarin. Using the Naranjo scoring system, a method to determine the relative probability of an adverse event associated with drug administration, the interaction was classified as ‘probable’ based on a total score of 5 (table 2).

Table 2.

Naranjo scoring for probability of warfarin-muscadine grape interaction

| Naranjo questionnaire8 | Yes | No | Do not know | Case score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Are there previous conclusive reports on this reaction? | 1 | 0 | NA | 0 |

| 2. Did the adverse event appear after suspected drug was administered? | 2 | −1 | NA | 2 |

| 3. Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued or a specific antagonist was administered? | 1 | 0 | NA | 1 |

| 4. Did the adverse reaction reappear when the drug was readministered? | 2 | −1 | NA | NA |

| 5. Are there alternative causes (other than the drug) that could on their own have caused the reaction? | −1 | 2 | NA | −1 |

| 6. Did the reaction reappear when a placebo was given? | −1 | 1 | NA | NA |

| 7. Was the drug detected in blood (or other fluids) in concentrations known to be toxic? | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| 8. Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased, or less severe when the dose was decreased? | 1 | 0 | NA | 1 |

| 9. Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drug in any previous exposure? | 1 | 0 | NA | 1 |

| 10. Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence? | 1 | 0 | NA | 1 |

| Total score | 5 |

NA, not applicable.

The Naranjo scoring system categories adverse reactions as follows: 9 is definite, 5–8 is probable, 1–4 is possible and 0 is doubtful.8 When scuppernong intake was significantly limited, the patient's INR declined and then remained therapeutic. This interaction has the potential to have implications on warfarin management in patients consuming muscadine grapes in Southeastern USA and those consuming quercetin-containing foods or quercetin supplements worldwide.

The patient has been on long term warfarin therapy and prior to scuppernong season had multiple labile INRs, primarily subtherapeutic, at doses ranging from 61 to 74 mg weekly. The patient had historically required higher doses of warfarin to achieve therapeutic INRs (target range 2–3). In the previous scuppernong season, the patient did have a supratherapeutic INR (5.7), but the intake of scuppernongs was not identified at that time. Therefore, the volume of fruit consumed during that time is not known as well. The fact that scuppernong intake and warfarin dose were simultaneously decreased producing numerous therapeutic INRs is an important confounding variable. However, the patient had several consecutive subtherapeutic INRs when taking warfarin 61–74 mg weekly prior to scuppernong season. In addition, the anticoagulation provider adjusted the warfarin dose by small percentages on evidence-based algorithm in order to avoid large INR fluctuations. It is noteworthy that the patient's INR stabilised and was less erratic as the consumption of scuppernongs was controlled and decreased.

Owing to the widespread availability of quercetin, and at least in Southeastern USA the consumption of muscadine grapes such as scuppernongs, there is a reasonable need for caution and monitoring as more literature becomes available regarding the potential for flavonoid-induced drug interactions with warfarin.

Learning points.

In patients that continue to have erratic International Normalised Ratios (INRs), a history of dietary intake including foods that do not contain vitamin K may help identify a possible cause.

Patients should be made aware of the potential for warfarin interactions with quercetin-containing products and patients should be encouraged to speak with healthcare providers before starting any herbal or dietary supplement.

Frequent INR monitoring in patients on warfarin, a medication with a narrow therapeutic index, is essential due to the potential for various interactions with foods and other drugs.

More research is needed to determine the clinical relevance of the quercetin-warfarin interaction and to evaluate the impact of quercetin consumption at different quantities on warfarin monitoring.

Footnotes

Contributors: CW, ZD, KD, AD and EH provided substantial contribution to manuscript design, data interpretation, drafting as well as revising the manuscript and final approval of the version submitted.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Aston JL, Lodolce AE, Shapiro NL. Interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice. Pharmacotherapy 2006;26:1314–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastrana-Bonilla E, Akoh CC, Sellappan S, et al. Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of muscadine grapes. J Agric Food Chem 2003;51:5497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talcott ST, Lee J. Ellagic acid and flavonoid antioxidant content of muscadine wine and juice. J Agric Food Chem 2002;50:3186–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boots AW, Haenen GRMM, Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur J Pharmacol 2008;585:325–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hapner CD, Deuster P, Chen Y. Inhibition of oxidative hemolysis by quercetin, but not other antioxidants. Chem Biol Interact 2010;186:275–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Bari L, Ripoli S, Pradhan S, et al. Interactions between quercetin and warfarin for albumin binding: a new eye on food/drug interference. Chirality 2010;22:593–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Si D, Wang Y, Zhou YH, et al. Mechanism of CYP2C9 inhibition by flavones and flavonols. Drug Metab Dispos 2009;37:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]