Abstract

Context:

Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad and Wendl (Kaṇṭakāri) is a diffuse herb with prickly stem, traditionally used for the treatment of inflammation and one in the group of daśamūla (group of ten herbs) herbs commonly used drug in Ayurveda.

Aims:

In continuation of search for potent natural anti-inflammatory agents, the present research work was planned to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extract of S. xanthocarpum whole plant.

Settings and Design:

The ethanol extract was evaluated at dose 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg p.o. in rats.

Materials and Methods:

Using pharmacological screening models carrageenan induced rat paw edema, histamine induced rat paw edema and cotton pellet granuloma in rats.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data obtained was analyzed statistically using analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Dunnett test, P < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Results:

Acute treatment didn’t show anti-inflammatory activity against carrageenan and histamine induced paw edema. However, administration of 100 mg/kg p.o for 7 day reduced the granuloma formation in cotton pellet granuloma model.

Conclusions:

Present results support the traditional use of plant for anti-inflammatory activity. In brief, the results provide scientific pharmacological basis for the therapeutic use of S. xanthocarpum.

KEY WORDS: Anti-inflammatory, carrageenan, cotton pellet granuloma, histamine, Solanum xanthocarpum

INTRODUCTION

Disease, decay and death have always co-existed with life, study of diseases and their treatment must also have been contemporaneous with the dawn of the human intellect.[1] Inflammation is a complex set of interactions between soluble factors and cells that can arise in any tissue in response to traumatic, infectious, post-ischemic, toxic or autoimmune injuries.[2] Inflammation is widely recognized to be at the root of a host of serious human diseases from heart disease to diabetes and cancer.[3] Inflammation can be treated with steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[4] NSAIDs are the most widely used classes of medications, accounting for 3% (~70 million/year) of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. Some are available as over the counter drugs. All NSAIDs can cause serious side-effects, including stomach ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney failure, heart attacks and strokes. Adverse effects of NSAIDs are responsible for more than 100,000 hospitalizations and more than 16,000 deaths each year.[5]

Indeed, nearly 25% of today's conventional drugs originated directly or indirectly from plants.[6,7,8] Traditional medicinal plants are also rich sources of new potential drugs for treatment of inflammation.[9] Since plants have provided many drugs in the past and they remain a rich sources of novel compounds based on nature's combinatorial natural products chemistry over millions of years of evolution, they should be continued to be investigated as the source of novel therapeutic agents.[10]

Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad and Wendl. (Solanaceae) is a prickly diffuse bright green perennial herb, commonly known as Yellow Berried Nightshade (Kaṇṭakāri), woody at the base, 2-3 m height, found throughout India,[11,12] mostly in dry places as a weed on roadsides and waste lands.[13]

It is one of the daśamūla and a commonly used drug in Ayurveda. The plant is bitter, acrid, thermogenic, anthelmintic, anti-inflammatory, digestive, carminative, appetizer, stomachic, febrifuge, expectorant, laxative, stimulant, diuretic, rejuvenating, emmenagogue and aphrodisiac.[13] The plant contains alkaloids, sterols, saponins, flavonoids and their glycosides and also carbohydrates, fatty acids amino acids etc.[14]

Various activities are reported in the plant viz hepatoprotective,[15,16] anti-asthmatic,[17] antidiabetic,[18,19] antioxidant,[12,20,21] immunomodulatory,[22] wound healing,[23] diuretic,[24] antispermatogenic,[25] antifertility, antipyretic, anticancer, anti-allergic,[14] anthelmintic,[12] antimicrobial.[12,26,27] Extract of dried fruits of S. xanthocarpum and its combination with extract of dried fruits of Cassia fistula are reported to possess anti-inflammatory activity.[28]

According to the literature review, there is a paucity of scientific data for anti-inflammatory activity of the whole plant. The present research work, therefore, was initiated to investigate the anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extract of S. xanthocarpum whole plant in laboratory animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The plant material was collected from the local source in Satara district in Maharashtra state. The plant material was authenticated by Botanical Survey of India (Government of India Ministry of Environment and Forests), Pune.

Chemicals and other material

Carrageenan (Thermosil, Fine Chem., India), histamine (Research Lab Fine Chemical, India), distilled water, anesthetic ether (Rachana Ether Pvt. Ltd, India), ethanol, Surgical sutures (Johnson and Honson Ltd., India), Surgical cotton (Mamta Surgical Cotton Industries, India), Soxhlet apparatus, Plethysmometer (Orchid Scientific PLM02, India).

Extracts

The collected S. xanthocarpum plant material was made into small pieces, shade-dried and coarsely powdered using a pulverizer. The coarse powders were subjected to extraction with ethanol using Soxhlet apparatus. The extracts were collected and evaporated at atmospheric pressure and the last trace of the solvents was removed in-vacuo. The prepared extract was used for screening of anti-inflammatory activity.

Experimental animals

Wistar rats required for the study were obtained from Institute's animal house facility. They were housed in polypropylene cages, six animals per cage, in an air-conditioned area at 25 ± 2°C with 10:14 h light and dark cycle at relative humidity of 45-55%. They were given Nutrimix Std. 1020, laboratory animal diet (Nutrivet Life Sciences, Pune) animal feed and Aquaguard-purified water ad libitum. The food, but not water was withdrawn 3 h before the experiment.

Approval of the research protocol

The animal experiment was carried out after obtaining the approval of animal experimental protocol by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of Jayawantrao Sawant College of Pharmacy and Research, Hadapsar, Pune, constituted as per guidelines of “Committee for Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experimental Animals,” India.

Selection of dose and preparation of dosage form for pharmacological screening

The preliminary doses were selected based on the literature review and results of acute toxicity study. If the literature is devoid of any such reference then the 10 times less dose of lethal dose 50% (LD50) was the maximum dose and subsequent two more ½-log doses below the maximum dose level was selected for the preliminary study. Suitable dosage forms of extract were prepared on the day of the experiment.

Methods

Acute toxicity study

The acute oral toxicity (AOT) study of the extract was performed as per the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines 425 at a limit dose of 2000 mg/kg. Animals were observed individually at least once during the first 30 min after dosing, periodically during the first 24 h (with special attention given during the first 4 h) and daily thereafter, for total 14 days for sign of toxicity and/or mortality if any. The LD50 was calculated by using OECD 425 (AOT) software.

Carrageenan induced paw edema in rats

Male Wistar rats (225-250 g) were not fed food for 12 h with water ad libitum before the administration of drugs. Sixty min after the oral administration of a test drug (10, 30 and 100 mg/kg p.o.) vehicle or diclofenac sodium (10 mg/kg p.o.) and each rat was injected with freshly prepared suspension of 0.1 ml of 1% carrageenan into subplantar tissue of the right hind paw. Inflammation was measured plethysmographically using Plethysmometer (Orchid Scientific PLM02), at an interval of ½, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 24 h after carrageenan injection. Change in paw volume was calculated.[29]

Histamine induced paw edema in rats

Histamine, 0.1 ml of 1% was injected in the sub-plantar region for induction of inflammation in rat paw 1 h after the oral treatment with vehicle, test drug or diclofenac sodium. Inflammation was measured plethysmographically using plethysmometer (Orchid Scientific PLM02), at an interval of 0, ½ and 1 h after histamine injection.[30,31]

Cotton pellet induced granuloma in rats

Male Wistar rat (225-250 g) were selected and divided into five groups. Food was withheld 12 h before the experiment, with free access to water. The animals were treated with vehicle, test drug (100 mg/kg p.o.) or diclofenac sodium. Anesthesia was induced in animal with anesthetic ether 1 h after giving the first dose. A sterile cotton pellet weighing 20 mg was inserted one in each scapula region of rats by making small subcutaneous incision. The drug administration was continued for 7 days. On 8th day, animals were killed by giving excess anesthesia. The cotton pellets were removed, weighed and kept in a hot air oven at 60°C until the constant weight is achieved. The net dry weight of pellet and the percent change of the granuloma weight were calculated by applying statistical test.[29] The level of inhibition of granuloma tissue development was calculated using the formula:

[Tc − Tt/Tc] × 100

where Tc = weight of granuloma tissue of the control group; Tt = weight of granuloma tissue of treated group.[32]

Statistical analysis

The interpretation of the results was performed by applying statistical analysis, which included one-way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Dunnett test, P < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

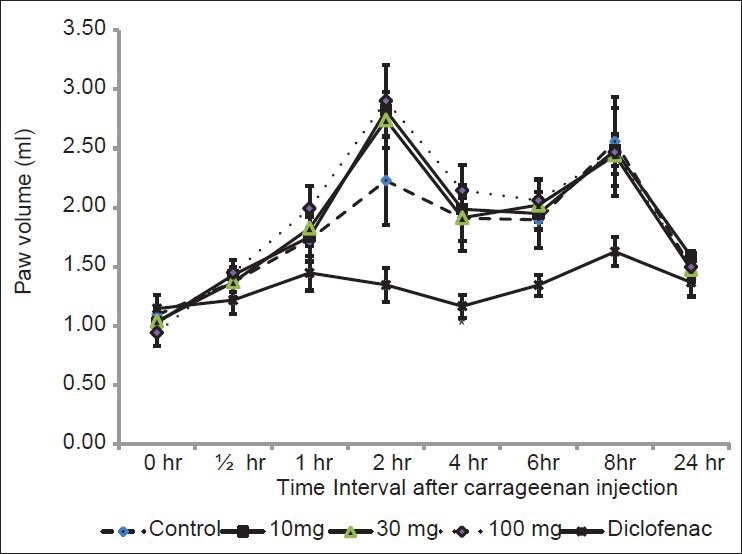

Carrageenan induced edema in rat paw

Subcutaneous injection of carrageenan 0.1 ml of 1% solution in the sub-plantar region induced edema in rat paw in the control group. The administration of S. xanthocarpum extract (SxE) 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg p.o 1 h before carrageenan didn’t show anti-inflammatory activity at any time interval.

Diclofenac sodium showed a decrease in inflammation at all intervals, but significant (P < 0.05) decrease was observed only at 4 h [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Effect of ethanol extract of Solanum xanthocarpum on carrageenan induced paw edema in rats

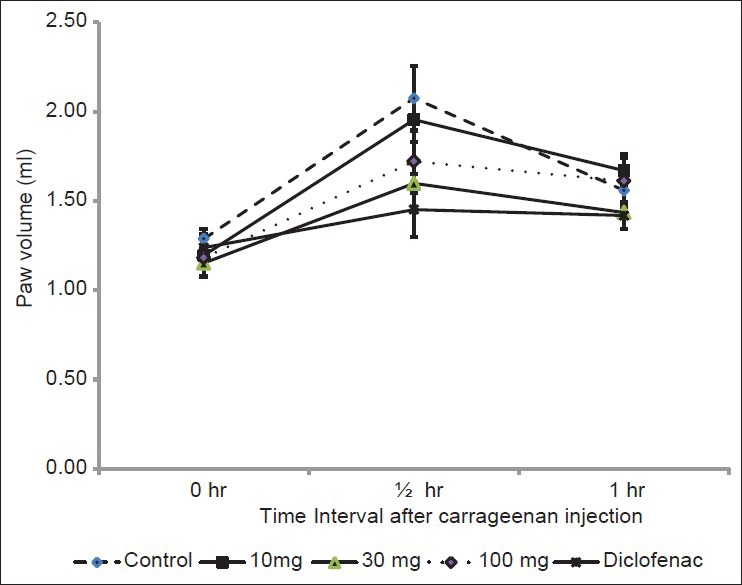

Histamine induced paw edema in rats

Administration of histamine subcutaneously in rat paw induced inflammation of paw in the control group. Administration SxE 10, 30 or 100 mg/kg p.o didn’t show significant changes in paw volume [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Effect of ethanol extract of Solanum xanthocarpum on histamine induced paw edema in rats

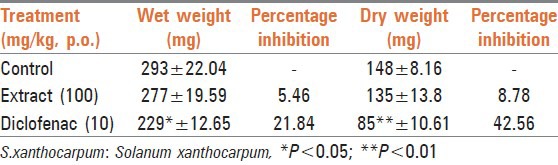

Cotton pellet granuloma in rats

The drug SxE at 100 mg/kg p.o. was able to reduce the inflammatory process of granuloma formation in rats after the treatment period of 7 days in comparison with vehicle [Table 1]; this was evident from the reduction of both wet and dry weights of the cotton pellets. However, reduction in weight of pallet in both cases was not significant. Treatment with diclofenac sodium (10 mg/kg p.o.) also significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the granuloma.

Table 1.

Effect of ethanol extract of S.xanthocarpum on cotton pellet granuloma in rats

DISCUSSION

The methods employed to screen these compounds for anti-inflammatory activity may involve transudative, exudative or proliferative phases of the inflammatory reactions.[33]

The most widely used primary test for screening of anti-inflammatory agents is carrageenan induced edema in the rat hind paw. Vinegar et al. (1969)[34] described carrageenan induced edema in the paw of the rat as a biphasic event, early or first phase and late or second phase. Early phase results from histamine, serotonin and bradykinin liberation while the late phase is associated with the formation of prostaglandins. In addition, neutrophil infiltration, release of free radicals viz hydrogen peroxide, superoxide and hydroxyl radicals from neutrophils play a role in the late phase of carrageenan-induced inflammation. Cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes also play roles in the formation of carrageenan-induced edema. The suppression of the first phase may be attributed to inhibition of the release of early mediators, such as histamine and serotonin and action in the second phase may be explained by an inhibition of cyclooxygenase.[35]

The result of the present study indicates that SxE at 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg was unable to reduce inflammation induced by carrageenan. Diclofenac sodium at 4 h showed a significant decrease in inflammation supporting its well-proven cyclooxygenase pathway inhibition mechanism. Histamine is one of the important inflammation mediators because of its potent vasodilation and vascular permeability actions. Histamine H1 receptors are involved in mediating the inflammation induced by various inflammatory agents.[36] Histamine induced paw edema is a well-established model to study inflammation and neutrophil infiltration in paw tissue. Several reports have confirmed that histamine alone and in association with chemo-attractants such as platelet activating factor, interleukin 8 and leukotriene B4 is involved in the regulation of neutrophil recruitment.[37]

In the present study, ethanolic extract of S. xanthocarpum showed non-significant changes in the histamine induced paw edema.

Cotton pellet implantation is the most suitable method for studying the efficacy of drugs against proliferative phase of inflammation.[33] The cotton pellet granuloma method has been widely employed to assess the transudative, exudative and proliferative components of chronic inflammation and is a typical feature of established chronic inflammatory reaction. The fluid absorbed by the pellet greatly influences the wet weight of the granuloma and the dry weight correlates well with the amount of granulomatous tissue formed. In chronic inflammation, monocyte infiltration and fibroblast proliferation take place. This proliferation becomes widespread by the proliferation of small vessels or granuloma. NSAIDs decrease the size of granuloma, which results from cellular reaction by inhibiting granulocyte infiltration/inflammation, preventing generation of collagen fibers and suppressing mucopolysaccharides.[38] In the present investigation, the SxE 100 mg/kg showed a non-significant decrease in the wet weight and dry weight of the cotton palette granuloma indicating that chronic administration of the drug reduces the proliferation of fibroblast as well as fluid accumulation in chronic inflammation in a weak manner.

In conclusion, ethanol extract of S. xanthocarpum on acute oral administration was unable to reduce inflammation induced by carrageenan and histamine; however, on chronic administration it exhibits weak reduction of the granuloma formation suggesting its role in the inhibition of proliferative phase of the inflammation. In Ayurvedic text S. xanthocarpum fruits are recommended for the anti-inflammatory activity. It is also scientifically proved that extract of dried fruits of S. xanthocarpum possess anti-inflammatory activity at 500 mg/kg p.o.[28] In the present study whole plant extract was used at the maximum dose 100 mg/kg p.o. which may not be sufficient to produce the anti-inflammatory effect in the acute phase; however in chronic administration, it reduced the proliferative phase of inflammation. The anti-inflammatory activity after chronic administration of SxE is found non-significant, which may be due to the less quantity of chemical constituent present in whole plant as compare to fruits alone. Thus, present study supports the recommendation of fruits instead of whole plant for the treatment of inflammation in traditional medicinal system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are thankful to Professor T. J. Sawant JSPM, Pune Maharashtra for providing necessary facilities to conduct the research work. Authors are also thankful to assistant professors Ms. Farhin Khan and Ms. Ramya Murthy for their contribution in this research work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Dehradun: International Book Distributors; 2008. Indian medicinal plants; p. 1760. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–52. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolattukudy PE, Niu J. Inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CCR2 pathway. Circ Res. 2012;110:174–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunton LL, Parker KL, editors. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. Goodman and gilman's manual of pharmacology and therapeutics; pp. 434–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.101 Truman Avenue Yonkers, NY: Consumers Union of United States, Inc; 2011. Consumer Reports Health Best Buy Drugs. The Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Treating Osteoarthritis and Pain; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Smet PA. The role of plant-derived drugs and herbal medicines in healthcare. Drugs. 1997;54:801–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlini EA. Plants and the central nervous system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:501–12. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton PJ, Seth P. Plants and the central nervous system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:497–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calixto JB, Otuki MF, Santos AR. Anti-inflammatory compounds of plant origin. Part I. Action on arachidonic acid pathway, nitric oxide and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB) Planta Med. 2003;69:973–83. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillipson JD. 50 years of medicinal plant research-Every progress in methodology is a progress in science. Planta Med. 2003;69:491–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma PC, Yelne MB, Dennis TJ. Vol. 4. New Delhi: C.C.R.A.S., Dept of ISM and H, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India; 2001. Database on medicinal plants used in Ayurveda; pp. 269–87. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardhi P, Jain PA, Ganeshpurkar A, Rai G. Anti-microbial, anti-oxidant and anthelmintic activity of crude extract of Solanum xanthocarpum. Pharmacogn J. 2010;2:400–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roshy JC, Ilanchezhian R, Patgiri BJ. Therapeutic potentials of kantakari (Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad. and Wendl.) Ayurpharm Int J Ayur Alli Sci. 2012;1:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh OM, Singh TP. Phytochemistry of Solanum xanthocarpum: An amazing traditional healer. J Sci Ind Res. 2010;69:732–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R, Sharma AK, Sharma MC, Dobhal MP, Gupta RS. Evaluation of antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of lupeol in experimental hyperglycaemia. Nat Prod Res. 2012;26:1125–9. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.560845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain T, Gupta RK, Sweety K, Khan MS, Hussain MS, Arif M, et al. Evaluation of antihepatotoxic potential of Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract against antitubercular drugs induced hepatopathy in experimental rodents. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:454–60. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60075-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindan S, Viswanathan S, Vijayasekaran V, Alagappan R. A pilot study on the clinical efficacy of Solanum xanthocarpum and Solanum trilobatum in bronchial asthma. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;66:205–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kar DM, Maharana L, Pattnaik S, Dash GK. Studies on hypoglycaemic activity of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad. and Wendl. fruit extract in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;108:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poongothai K, Ponmurugan P, Ahmed KS, Kumar BS, Sheriff SA. Antihyperglycemic and antioxidant effects of Solanum xanthocarpum leaves (field grown and in vitro raised) extracts on alloxan induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:778–85. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain T, Gupta RK, Sweety K, Eswaran B, Vijayakumar M, Rao CV. Nephroprotective activity of Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and renal dysfunction in experimental rodents. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:686–91. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S, Sharma UK, Sharma AK, Pandey AK. Protective efficacy of Solanum xanthocarpum root extracts against free radical damage: Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant effect. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2012;58:174–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sultana R, Khanam S, Devi K. Immunomodulatory effect of methanol extract of Solanum xanthocarpum fruits. Int J Pharma Sci Res. 2011;2:93–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar N, Prakash D, Kumar P. Wound healing activity of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad. and Wendl. fruits. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:470–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel P, Patel M, Saralai M, Gandhi T. Antiurolithiatic effects of Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract on ethylene-glycol-induced nephrolithiasis in rats. J Young Pharm. 2012;4:164–70. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.100022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purohit A. Contraceptive efficacy of Solanum xanthocarpum berry in male rats. Anc Sci Life. 1992;12:264–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salar RK, Suchitra Evaluation of antimicrobial potential of different extracts of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad. and Wendl. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2009;3:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavimath CC, Kulkarni SM, Raorane CJ, Kalsekar DP, Gavade BG, Ravishankar BE, et al. Antibacterial potentials of Solanum indicum, Solanum xanthocarpum and Physalis minima. Int J Pharma Appl. 2012;3:414–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anwikar S, Bhitre M. Study of the synergistic anti-inflammatory activity of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad and Wendl and Cassia fistula Linn. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:167–71. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.72489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel HG, editor. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. Drug discovery and evaluation: Pharmacological assays; pp. 670–1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arulmozhi DK, Veeranjaneyulu A, Bodhankar SL, Arora SK. Pharmacological investigations of Sapindus trifoliatus in various in-vitro and in-vivo models of inflammation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005;37:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kale M, Misar AV, Dave V, Joshi M, Mujumdar AM. Anti-inflammatory activity of Dalbergia lanceolaria bark ethanol extract in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang QM, Zhang H, Cao Y, Wang C. Anti-inflammatory and free radical scavenging activities of ethanol extracts of three seeds used as “Bolengguazi”. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radhika P, Rao PR, Archana J, Rao NK. Anti-inflammatory activity of a new sphingosine derivative and cembrenoid diterpene (lobohedleolide) isolated from marine soft corals of Sinularia crassa TIXIER-DURIVAULT and Lobophytum species of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1311–3. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vinegar R, Schreiber W, Hugo R. Biphasic development of carrageenin edema in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969;166:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suleyman H, Gul HI, Gul M, Alkan M, Gocer F. Anti-inflammatory activity of bis (3-aryl-3-oxo-propyl) methylamine hydrochloride in rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:63–7. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arya S, Kumar VL. Antiinflammatory efficacy of extracts of latex of Calotropis procera against different mediators of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:228–32. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamaddonfard E, Farshid AA, Hosseini L. Crocin alleviates the local paw edema induced by histamine in rats. Avicenna J Phytomedicine. 2012;2:97–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramprasath VR, Shanthi P, Sachdanandam P. Anti-inflammatory effect of Semecarpus anacardium Linn. nut extract in acute and chronic inflammatory conditions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:2028–31. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]