Abstract

The challenges faced in delivering lifesaving vaccines to the targeted beneficiaries need to be addressed from the existing knowledge and learning from the past. This review documents the history of vaccines and vaccination in India with an objective to derive lessons for policy direction to expand the benefits of vaccination in the country. A brief historical perspective on smallpox disease and preventive efforts since antiquity is followed by an overview of 19th century efforts to replace variolation by vaccination, setting up of a few vaccine institutes, cholera vaccine trial and the discovery of plague vaccine. The early twentieth century witnessed the challenges in expansion of smallpox vaccination, typhoid vaccine trial in Indian army personnel, and setting up of vaccine institutes in almost each of the then Indian States. In the post-independence period, the BCG vaccine laboratory and other national institutes were established; a number of private vaccine manufacturers came up, besides the continuation of smallpox eradication effort till the country became smallpox free in 1977. The Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) (1978) and then Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) (1985) were launched in India. The intervening events since UIP till India being declared non-endemic for poliomyelitis in 2012 have been described. Though the preventive efforts from diseases were practiced in India, the reluctance, opposition and a slow acceptance of vaccination have been the characteristic of vaccination history in the country. The operational challenges keep the coverage inequitable in the country. The lessons from the past events have been analysed and interpreted to guide immunization efforts.

Keywords: Eradication, India, smallpox, vaccination, vaccines

Introduction

Vaccination is a proven and one of the most cost-effective child survival interventions1. All countries in the world have an immunization programme to deliver selected vaccines to the targeted beneficiaries, specially focusing on pregnant women, infants and children, who are at a high risk of diseases preventable by vaccines. There are at least 27 causative agents against which vaccines are available and many more agents are targeted for development of vaccines1,2. The number of antigens in the immunization programmes varies from country to country; however, there are a few selected antigens against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, poliomyelitis, measles, hepatitis B which are part of immunization programmes in most of the countries in the world. The first vaccine (small pox) was discovered in 1798. The most striking success of these efforts has been the eradication of smallpox disease from the planet1,2,3. Though a proven cost-effective preventive intervention, the benefits of immunization is not reaching to many children who are at the maximum risk of the diseases preventable by these vaccines. Majority of the children who do not receive these vaccines live in developing countries. As per the recent nation-wide survey data, of the targeted annual cohort of 26 million infants in India, only 61 per cent had received all due vaccines4. Understandably, the implementation of vaccination programme and ensuring that the benefits of vaccines reach to each and every possible beneficiary is a challenging task. This review documents the history of vaccines and vaccination in India and analyses the events of past to provide policy direction for the vaccination efforts in the country. The focuses is on broader events and it does not address detailed operational aspects of immunization programme in the country; however, the selected global timelines and events have been referred to provide a context and perspective.

Ancient times till first documented smallpox vaccination in India in 1802

The history of vaccines and vaccination starts with the first effort to prevent disease in the society3,5,6. Smallpox (like many other infectious diseases including measles) was well known since ancient times and believed to have originated in India or Egypt, over 3,000 years ago7,8,9,10. This was subject of observation for many learned minds and physicians such as Thucydides in 430 BC and Rhazes (also known as Abu Bakr) in 910 AD who reported that people affected by smallpox were protected from the future infections14. Abu Bakr also gave the initial (and probably the first) account of distinguishing measles and smallpox in 900 AD. From India, there are a few descriptions of occurrence of disease; however, one of the best recorded smallpox epidemics was reported from Goa in 1545 AD, when an estimated 8,000 children died14. Historians and physicians have sometimes referred smallpox as ‘Indian Plague’, which suggests that the disease might be widely prevalent in India in the earlier times.

The evidence indicates that smallpox inoculation was practiced in China in around 1000 AD and in India, Turkey, and probably Africa as well3,9,10,11,12. The inoculation, ‘the process of injecting an infective agent in a healthy person, which leads to often mild disease and preventing that individual from future serious disease’ was common in India12. Inoculation with smallpox virus material called variolation preceded smallpox vaccination and was one of the accepted approaches to protect from the disease. Inoculation was widely practiced in India (and later on, even a ban by Bengal Presidency in 1804 had limited effect on the practice)12. A detailed description of the practice of inoculation in India was given by Dr JZ Holwell in 1767 to the President and other members of Royal College of Physicians in London13. (The inoculation practice has been documented from different parts of India, especially in Bengal and Bombay presidencies6) however, there is a limited record of how many people were annually inoculated from smallpox matter in India during that period.

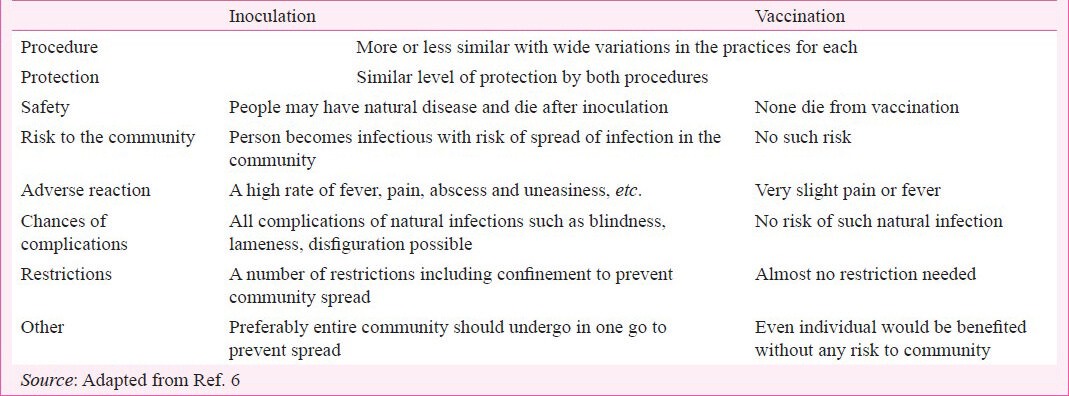

Smallpox affected all races and all regions of the world, with frequent epidemics and inoculation was practiced in a number of countries in East; however, the practice reached Europe especially in the United Kingdom not before early 18th century12. Knowing the severity of disease, various approaches were tried to prevent the scourge. Benjamin Jesty, an English farmer and cattle-breeder, in 1774 conducted an experiment with cowpox matter inoculation on his wife and two children and had almost discovered the first smallpox vaccine8. Twenty two years later, Edward Jenner made similar observation in milk-maids and noticed that a person inoculated with cow-pox virus, would develop a mild cowpox disease, with no serious risks and would be protected from future smallpox infections. Jenner's observation was his discovery of smallpox vaccine. Jenner published his observation in his seminal work titled ‘An enquiry into the causes and effects of Variolae Vaccinae’ in 1798. Soon after Jenner's publication, the smallpox vaccination spread to many parts of the world, especially Europe and America. The smallpox vaccine reached India in 1802 (within 4 years)12,13,14. The smallpox vaccination had some significant differences and advantages over variolation (Table I) which made smallpox vaccination immediately and widely accepted4,5,6.

Table I.

Difference in inoculation and vaccination

Vaccination in India (1802-1899)

The first doses of smallpox vaccine lymph in India arrived in May 1802. Anna Dusthall, a three year old child from Bombay (now Mumbai) became the first person in India to receive smallpox vaccine on June 14, 18026. From Bombay, through human chain of vaccinees, the smallpox vaccine as lymph was sent to Madras, Poona (Pune), Hyderabad and Surat14. The proven benefits of smallpox vaccination had such impact that variolation was outlawed in many European countries and also in some provinces of India as early as 1804. There were special efforts done by officials of Indian Medical Services to popularise smallpox vaccination. The uptake in the general public was low due to several reasons including need to pay a small fee for vaccination, belief in the practice of inoculation and that the disease was a wrath of goddess and many other misconceptions. Another major factor was organized oppositions by erstwhile ‘Tikadaars’ (who were involved in variolation) to smallpox vaccination fearing that they might lose their jobs. In fact, the variolation continued to be practiced in India even after ban and till early and mid-Twentieth century6,13,14. In the initial years, all the lymph required for vaccination was coming from England and then kept alive through chain of volunteers for further vaccination in India. By 1850 AD, as vaccine coverage increased, the challenges such some post-vaccination deaths, post-operative complications and unsuccessful vaccine take raised programmatic difficulties. This was complicated by resistance from some Hindus on pretext of vaccine coming from cow, which is considered a sacred animal6,13,14,15.

The vaccination was conducted by identified limited numbers of ‘trained vaccinators’, who would travel from one place to another and often termed as ‘travelling vaccinators’. These vaccinators were licensed to conduct vaccination (thus also called “Licensed vaccinators’) and not paid by government, thus would charge a small fee for vaccination from beneficiaries. This fee became a major reason for low coverage in rural areas and by the poor people. Later on, to address this challenge the concept of ‘Paid vaccinators’ came, who were hired as salaried employees by provincial governments to administer vaccination in rural areas and were paid by the government. The system of ‘Paid vaccinators’ was started in the second half of the 19th century15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

The vaccination in the 19th century was implemented through ‘vaccination and sanitary departments’ and the Sanitary Commissioners were in-charge of these efforts. However, the structure and approaches adopted in each province varied slightly. The vaccination would be offered through ‘dispensaries’ in urban areas, which would also act as a store for vaccine lymph. There were a few variations i.e. Bombay system of vaccination, started in 1827, was largely reliant on touring/travelling vaccinators, responsible for vaccination circles or subdivisions. Later on, Bombay system became most widely used approach in other provinces of India. Nearly two third of vaccination used to be done by touring vaccinators and rest at the dispensary system in India13,14,15.

The Compulsory Vaccination Act was passed in India in 1892 to ensure higher coverage with smallpox and reduce the epidemic. The ‘Act’ largely remained on the papers except at the times of epidemics. On records, the law was in force in approximately 80 per cent of the districts of British India in 19386.

Vaccine availability and manufacturing in India (1802-1899)

Smallpox matter was used for inoculation and the material used for smallpox vaccination was lymph from cowpox matter. The early vaccines (or vaccine matters, as called often) were not made in manufacturing units. It was lymph collected from cows after vaccinating them with cowpox matter. Subsequently, there were a few improvisations in form of vaccine farms and cow farms for production of vaccine lymph in different parts of the world.

In India, till 1850, the vaccine was imported from Great Britain. However, there were real logistic challenges in transport of vaccine to India. The increased demand in later years led to the shortage of vaccine or lymph in the country and mandated the Government of India to find alternatives for increasing sustained vaccine supply. There are records of a few research efforts in Bombay (Mumbai) as early as 1832 and the animal experiments for lymph started in Madras (now Chennai) in 1879, with initial success in 18806,15,16,17,18,19. In later part of the 19th century, with increased vaccine material supply, the research focus shifted to an effective preservation technique to ensure transport of vaccine material to the rural and difficult to access areas. As early as in 1895, glycerine was used in India for efficient transport of vaccine material as glycerinated lymph paste. Lanoline and Vaseline were other preservatives used in India. Vaccine with boric acid, which was also reported to be effective, was developed in 19257,8.

Another important event of this period was a cholera epidemic in Bengal and other parts of India. Following a recommendation of British Government, the Government of India accepted a request of Dr Haffkine to come and conduct Cholera vaccine trial in India. In 1893, Dr Haffkine conducted vaccine trials in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, and showed the efficacy of his vaccine in the effective control of the disease. Though Haffkine knew the process for the development of cholera vaccine, he had proven its efficacy here in India21 (and Personal Communication: Dr Abhay Choudhury, Director, Haffkine Institute, 2012). A plague epidemic started in India in 1896 (which led to the enactment of Epidemic Act of 1896, which is still applicable in the country). The Government of India requested him to work on the development of plague vaccine and provided him a two-room set in Grant Medical College, Mumbai, to set up his Laboratory. Dr Haffkine developed plague vaccine in 1897 and it is arguably, the first vaccine developed in India. This laboratory was called Plague Laboratory since 1899, renamed as Bombay Bacteriological Lab in 1905 and then finally named as Haffkine Institute in 1925, as it is known today22,23.

Vaccination in India (1900-1947)

The beginning of twentieth century witnessed a few socio-scientific-geopolitical events, which had lasting effect on vaccination efforts in the country. These changes were:

(i) Outbreak of cholera and plague in India (1896-1907) and the services of already limited number of vaccinators were diverted to epidemic control efforts,

(ii) The First World War (1914-1918) started and with coinciding Influenza Pandemic (which reportedly killed around 17 million Indians) became a priority for the Government,

(iii) New scientific understanding that two doses of smallpox vaccine would be needed for long lasting protection. It was a challenge considering that it meant convincing people to get vaccinated twice with perceived inconvenient and painful procedure6.

(iv) Most significantly, the Government of India Act of 1919, which devolved a number of administrative powers from Centre to Provinces, by which the local self-governments were assigned the responsibilities of providing health services, including smallpox vaccination. (The health service delivery being a State subject in India has an origin in this Act).

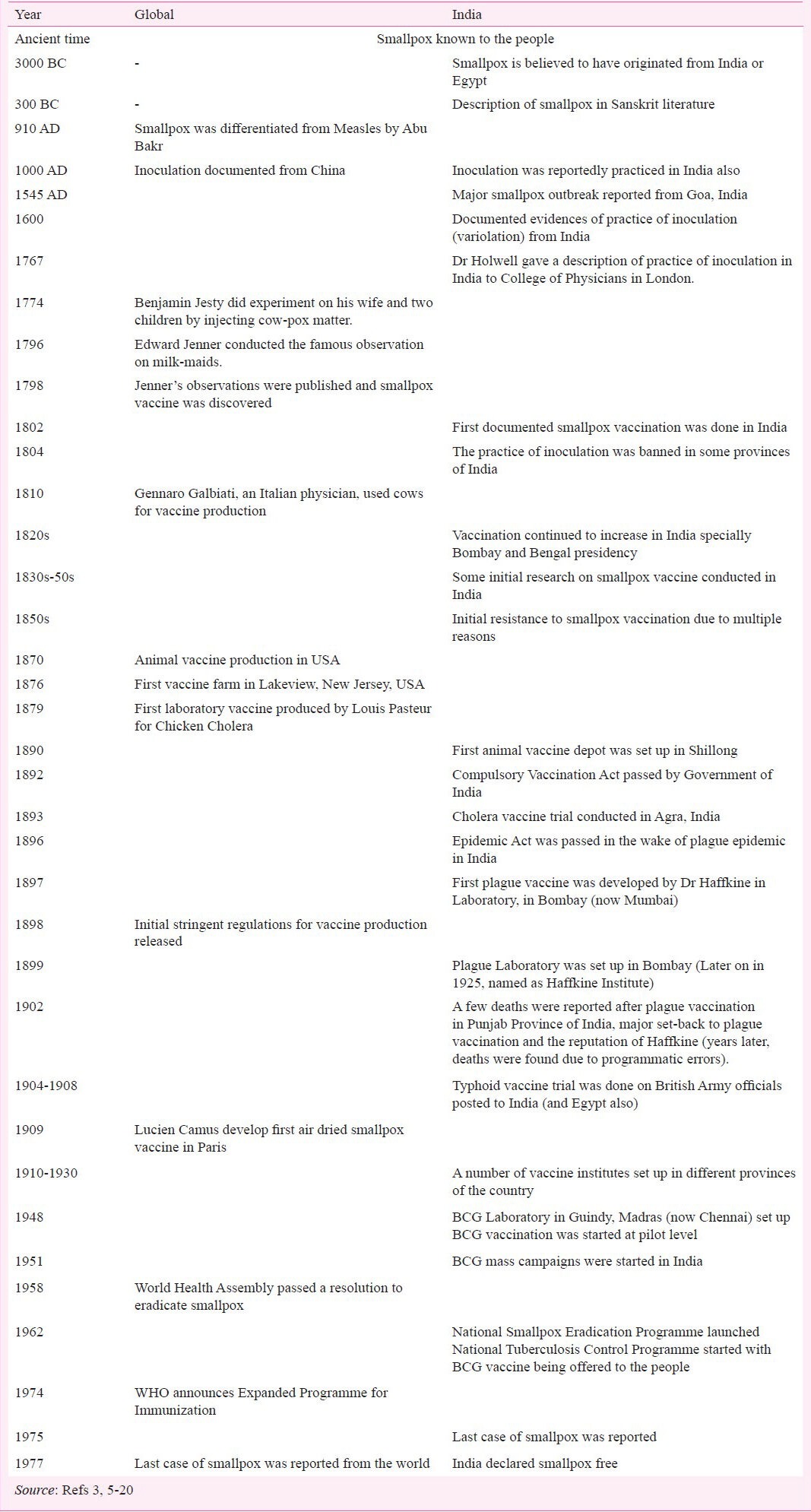

This period provides an insight as to how socio-political situation can adversely affect health of the people. Specially, ‘The 1919 Act’ originated with good intentions but the local government had limited financial capacities to fund vaccinators and often led to the variable efforts and progress on smallpox vaccination. The vaccination efforts continued with variable progress till 1939, when World War II was started. Vaccination efforts, though still a focus of local administration, became a casualty of the war. The vaccination coverage went down and in 1944-1945 in India, the highest numbers of smallpox cases in the last two decades were reported. As soon as the World War II ended, the focus was brought back on smallpox vaccination and cases decreased suddenly4,6,14,15,16. Another important milestone of this period was the typhoid vaccine trials in India between 1904-1908. The Anti-typhoid Committee of British Army Medical Department carried out extensive trial of vaccine in 24 units of British Army, joining their operations in India and Egypt24,25. The Committee compared the attack rate of typhoid amongst volunteers for vaccination and amongst non-volunteers in Army (and thus non-vaccinated) individuals and reported six-fold decrease in attack rate amongst vaccinated. Though the methods were not strictly scientific and received adverse criticism, the trial had decisive influence on the decision making on typhoid vaccination24,25,26. The important milestones related to vaccination in India are summarised in Table II.

Table II.

Timeline of vaccination efforts in India (Ancient time - till 1977)

Vaccine availability and manufacturing in India (1900-1947)

There were many units manufacturing smallpox lymph for vaccination at the beginning of this century. Additionally, cholera and plague vaccines were being produced in the country. One major event of this time was death of a few people in Punjab province after plague vaccination in 1902. Officials blamed Dr Haffkine for poor quality of vaccine and he was relieved from his position. Later on, the matter was investigated by eminent scientist such as Sir Ronald Ross and it was found that the same batch of plague vaccine was safely administered to many other places and these deaths were due to a contamination of vaccine vial. Dr Haffkine was exonerated and offered to be the Director of Haffkine institute, which he declined22,23. The deaths following vaccination were also reported after smallpox vaccination in all these years of vaccination; however, this event of death after plague vaccine in Punjab can arguably be called the first systematically documented Adverse Event Following Immunization (AEFI) investigation in India. The plague vaccination suffered major setback after this event. This event highlights the risk as to how AEFI can adversely affect the vaccination programme. It also highlights the need for a more robust and detailed procedure for investigation of deaths following vaccination which has become crucial platform for a functioning immunization programme in the recent times.

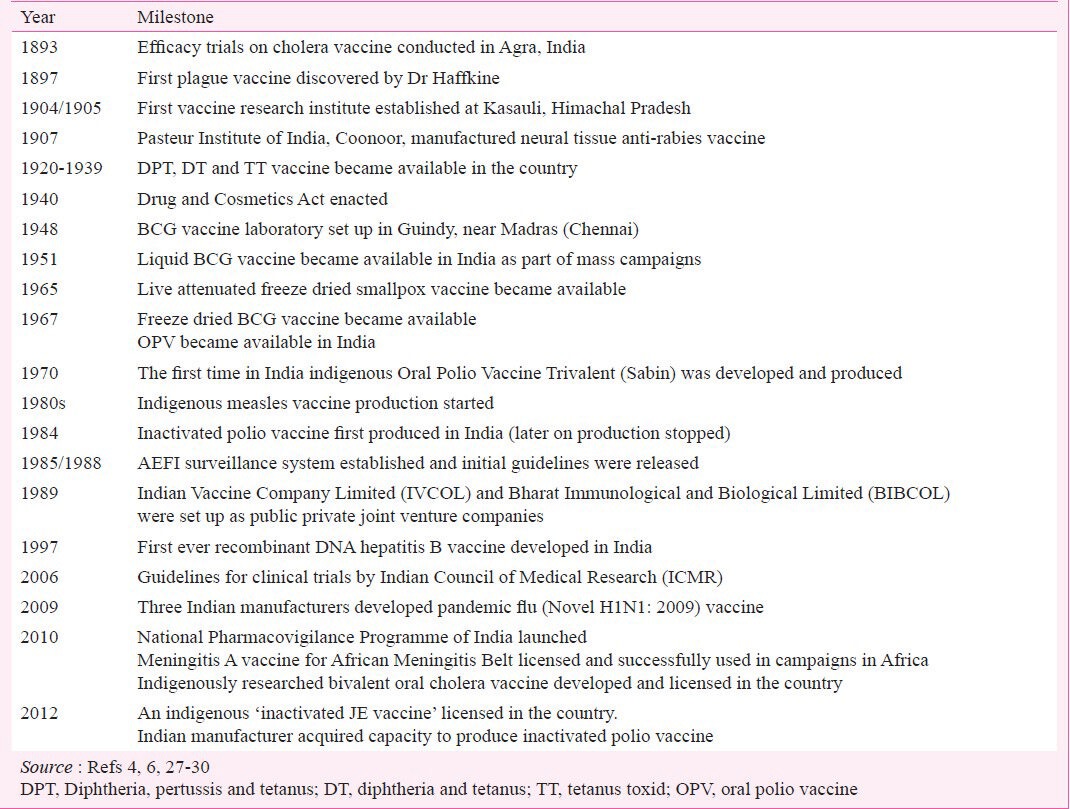

In early twentieth century, at least four vaccines (smallpox, cholera, plague, and typhoid) were available in the country. However, the major challenge was the shift of smallpox vaccination to two dose schedule. This had an important implication in the form of additional vaccine requirement. Considering this, the Government of India decided to set up new vaccine institutes. The initial vaccine research unit was Haffkine Institute for plague vaccine. The smallpox vaccine lymph was being produced in Shillong and a few other places since 18906. In 1904/1905, Central Research Institute was set up in Kasauli, Himachal Pradesh and then Pasteur Institute of Sothern India (as it was known then) in Coonoor in 1907 (Table III)4,6,27,28,29,30,31. The Pasteur Institute of India (PII) produced neural tissue Anti-rabies vaccine in 190728. The PII in due course of years, developed influenza vaccines, trivalent oral polio vaccines conducted landmark research and production of tissue culture and then Vero cell derived DNA purified rabies vaccine for human use28.

Table III.

Major milestones in vaccine developments and licensing in India

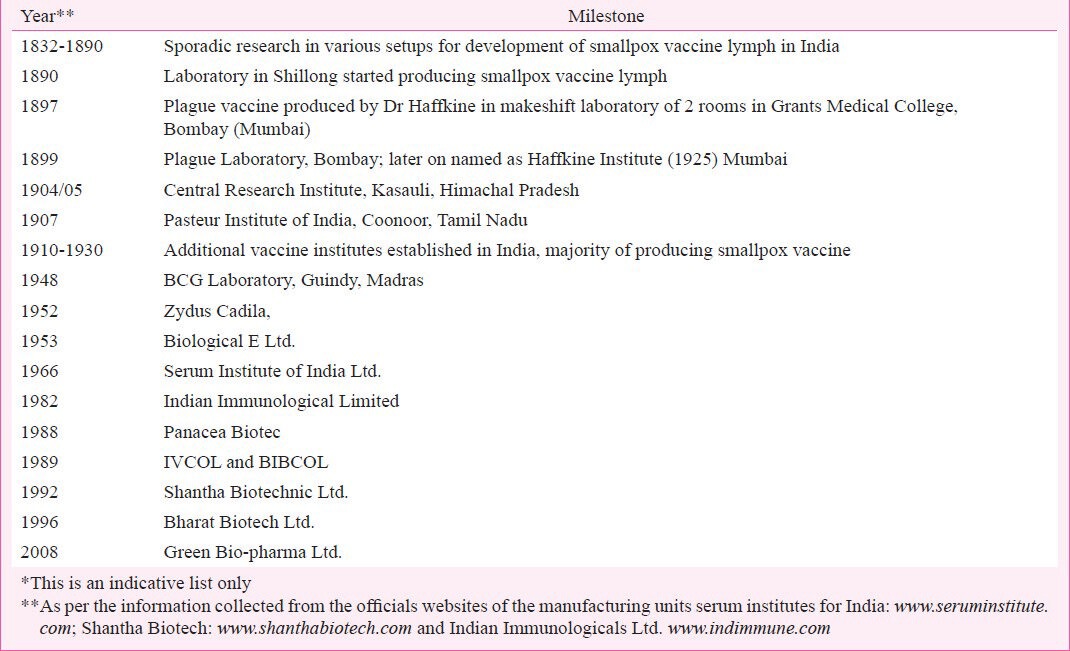

In the next few years, then Government set up an institute for smallpox vaccine lymph production in each of the then provinces of the country. These institutes emerged as centre for vaccine and serum production and were also involved in quality research6 (Table IV). The research conducted in these institutes was focused on improving the quality of vaccines and also on the preservative to ensure long term stability of the vaccine material.

Table IV.

Year of start of vaccine manufacturing units in India*

Vaccination in post-independence India (1947-1977)

At the time of independence, India was reporting maximum number of smallpox cases in the world. The cholera and plague epidemics were occurring but focus on control of these diseases was restricted and discussions were on about overall health development. Sir Joseph Bhore committee report was just out. Limited budgetary availability had curtailed majority of the efforts.

Tuberculosis was perceived as a major cause of morbidity and mortality. In May 1948, the Government of India issued a press note stating that tuberculosis was “assuming epidemic proportions” in the country, and that it had “after careful consideration” decided to introduce BCG vaccination on a limited scale and under strict supervision as a measure to control the disease31. A BCG Vaccine Laboratory at King Institute, Guindy, Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, was set up in 194832. In August 1948, the first BCG vaccinations were conducted in India. The work on BCG had started in India as a pilot project in two centres in 1948. In 1949, the BCG vaccination was extended to schools in almost all States of India. The International Tuberculosis Campaign (ITC) supported Government of India in expansion and scale up of BCG vaccination. From February 1949, five ITC teams demonstrated BCG vaccination in various urban centres with the start of a small scale pilot in Madanapalle. In a Conference in the summer of 1951 attended by representatives of the State Government, a proposal for the extension of mass BCG Vaccination Campaign throughout India was endorsed. The Government of India prepared a Plan of Operations laying down the organizational set-up required in each State to cover the total young population during a five to seven year period. The BCG vaccination was expanded through mass campaigns in 1951. The ITC support ended in June 1951 and from July 1951, BCG vaccination was conducted by the Indian authorities in close cooperation with UNICEF, which continued to provide financial support, and WHO, which gave technical advice31,32,33,34. In 1955-1956, the BCG vaccination mass campaign covered all the States of the Indian Union35. BCG vaccination became a part of the National Tuberculosis Control Programme (NTCP), which was started in 196232. The related events of this period were establishment of Tuberculosis Chemotherapy Center, later known as Tuberculosis Research Center (TRC) in Madras (Chennai) (now renamed as National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis) in 1956 and that of National Tuberculosis Institute (NTI) in 195932.

There were targeted efforts to control TB and the efficacy of BCG vaccine in prevention of pulmonary TB was in questions, since the very beginning. However, BCG vaccination was the only available protective measure against TB. A large BCG trial named ‘Feasibility Study for TB Prevention Trial’ was conducted in Chingelput, Tamil Nadu. This trial was started in 1968, recruitment and fifteen year follow up for all cases was completed by 1987. The trial showed that BCG vaccination did not offer significant protection against TB of the lung which occurs mostly in adults. After that, in India BCG vaccination policy was revised and it was recommended to be given at an early age preferably before the end of the first year after birth by integrating under UIP. BCG vaccination policies in many other countries were also revised as a consequence of the Chingelput trial findings36. This could be termed as a big success story of Indian research institutes in conducting large scale vaccine efficacy trial.

During this period and since early 1950s, globally the expert started discussion on the possibility of the eradication of smallpox. After much deliberation in 1958, the World Health Assembly (WHA) passed a resolution to eradicate smallpox, an event which changed the entire public health in the years to come. Following this resolution, India started National Smallpox Eradication Programme (NSEP) in 1962, with an objective of successfully vaccinating entire population in the next three years4,17. The target in ‘attack phase’ was 80 per cent coverage and in ‘maintenance phase’ all newborns, infants and children at the age of 5, 10 and 15 yr were to be vaccinated. However, after five years of implementation, the coverage remained low and outbreaks were still being reported. This was because the difficult to access population was not being reached and many a times the same individuals were being vaccinated for inflating coverage17,18,19.

In 1967-1968, the smallpox eradication strategy was reformulated with increased focus on surveillance, epidemiological investigation of outbreaks and rapid containment drives. In 1969, the vaccination technique changed from antiquated ‘rotary lancet’ to a new ‘bifurcated needle technique’. Another major change was availability of a more potent, heat stable and freeze dried vaccine in 1971, replacing old liquid vaccine. Both these steps simplified the process and increased the vaccine uptake significantly17,18,19,20.

By mid 1973, efforts were successful in many parts and smallpox was largely restricted to Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar, West Bengal and a few other States. In the same year, a national mobilization of health workforce was done and intensive campaign started. In the first phase (July-August 1973) search and containment efforts were done. In the second phase, UP, Bihar, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh States were targeted between October to December 1973. Every village, every household in these States was visited to detect any suspected case within a period of one week. The next three weeks were spent in case investigation and doing containment operations by health staff. In 1974, following massive efforts, 188,000 cases and 31,000 deaths were reported due to smallpox. The Government of India intensified the search and containment and vaccination efforts. The last case was reported in 1975 and efforts to maintain surveillance continued thereafter also. The details of the events of during this period are provided in Table V. The world was declared free from smallpox on May 8, 1980 by the World Health Assembly4,17,18,19,20.

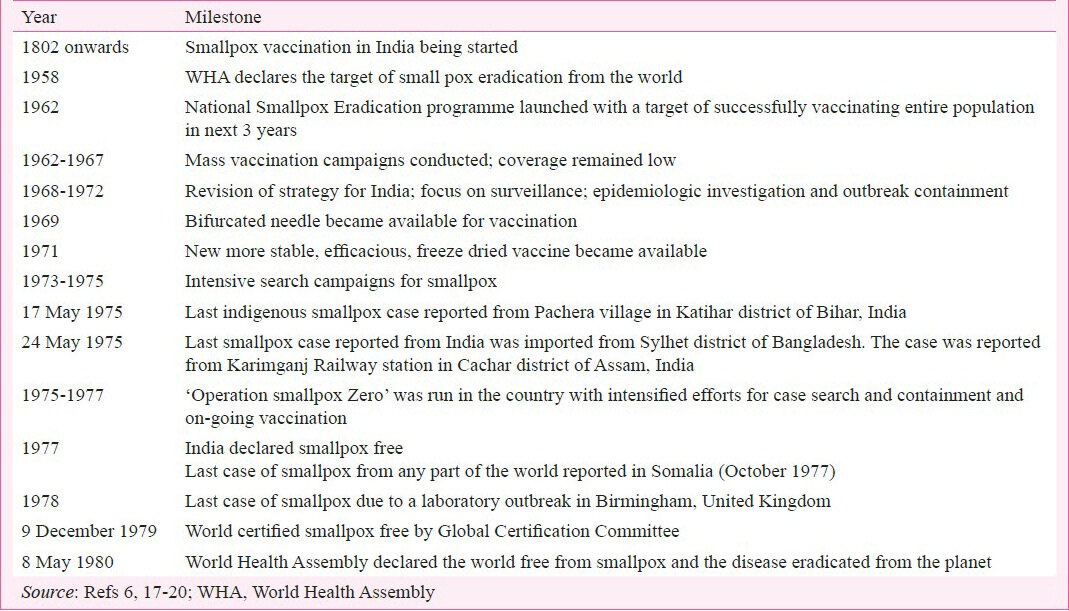

Table V.

Timeline of smallpox eradication

Vaccines availability and manufacturing in India (1947-1977)

India was self-sufficient in the production of smallpox vaccine at the time of independence. BCG vaccine laboratory was set up in Guindy in 1948 with the intention of sufficient BCG vaccine production for the requirement in the country32. The important development in vaccine manufacturing was setting up of vaccine manufacturing units in private sector also (Tables III–V). These units were involved in the production of vaccines other than smallpox also. The Pasteur Institute of India developed influenza vaccine in 1957 and an BPL inactivated rabies vaccine in 1970. This institute developed and produced, for the first time in India, indigenous trivalent oral polio vaccine (OPV) in 197030. According to an official statistics, there were nearly 19 vaccine manufacturing units in public sector and 12 in private sector in 197137. Majority of vaccines available in global market had become available in Indian market also. The vaccine manufacturing units in India were producing not only smallpox vaccines but a few of these were also producing diptheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT), diptheria and tetanus (DT), tetanus toxoid (TT), oral polio vaccine (OPV) and other vaccines except measles vaccine.

National Immunization Programme in India (1978 onwards)

Smallpox eradication left a legacy of improved health system, trained vaccinator, cold chain equipment and system and a network for surveillance of vaccine preventable diseases. Experts globally agreed to utilize this opportunity of trained workforce for better health and reduce child morbidities and mortality from other vaccine preventable diseases. The World Health Organization launched Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in 1974.

As soon as India was declared smallpox free in 1977, the country decided to launch National Immunization programme called Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) in 1978 with the introduction BCG, OPV, DPT and typhoid-paratyphoid vaccines29,30. The target in EPI was at least 80 per cent coverage in infancy, the vaccination was offered through major hospitals and largely restricted to the urban areas and thus understandably, the coverage remained low38. Typhoid-paratyphoid vaccine was dropped from EPI in 1981, reportedly due to considered higher reactogenecity and low efficacy of the vaccines and also due to perceived reduced burden of typhoid disease in the country. Tetanus toxoid vaccine for pregnant women was added in EPI in 198329,30,38. The EPI was rechristened with some major change in focus by the launch of Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) on November 19, 198531,32,40. The measles vaccine was added to the existing schedule. The objectives and major focus in UIP were: (i) rapidly increasing immunization coverage and reduction of mortality and morbidity due to six vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs), (ii) improve the quality of service, (iii), establish a reliable cold chain system till health facility level, (iv) phased implementation - all districts to be covered by 1989-1990, (v) introduce a district-wise system for monitoring and evaluation, and (vi) achieve self-sufficiency in vaccine production and manufacturing of cold chain equipment.

The immunization received additional importance when it was added to the Prime Minister's 20 point programme. Immunization was given the status of one of the five National Technology Missions launched in 198638. The Technology Mission on Immunization had the objectives of improving coverage with existing antigens, and developing self-sustainability in vaccine production. Both considered important for effective vaccination programme in the country38. The Child Summit of 1990 also brought attention on increasing immunization coverage and focus on a few interventions such as polio eradication, increasing coverage with the existing agents and maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination39,40.

The UIP started in 31 districts in 1985 with plan of scale up to additional districts. The coverage target was all pregnant women and 85 per cent of all infants against six VPDs by March 1990. With effect from 1990-1991, the vaccination programme became universalized in geographical coverage and the target of UIP was increased to cover 100 per cent of the infants41. In the beginning of UIP in 1985, the measles vaccine was being imported in India. The National Technology Mission on immunization helped in modernization and upgradation of vaccine facilities and by 1990-1991, the country became self-sufficient for all vaccines (including measles) except for OPV. Till March 1991, maintenance of cold chain was under contract between UNICEF and commercial agencies. From April 1991 onwards, states/union territories had taken responsibility of the maintenance of cold chain43. A detailed timeline of EPI and UIP in India is given in Table VI.

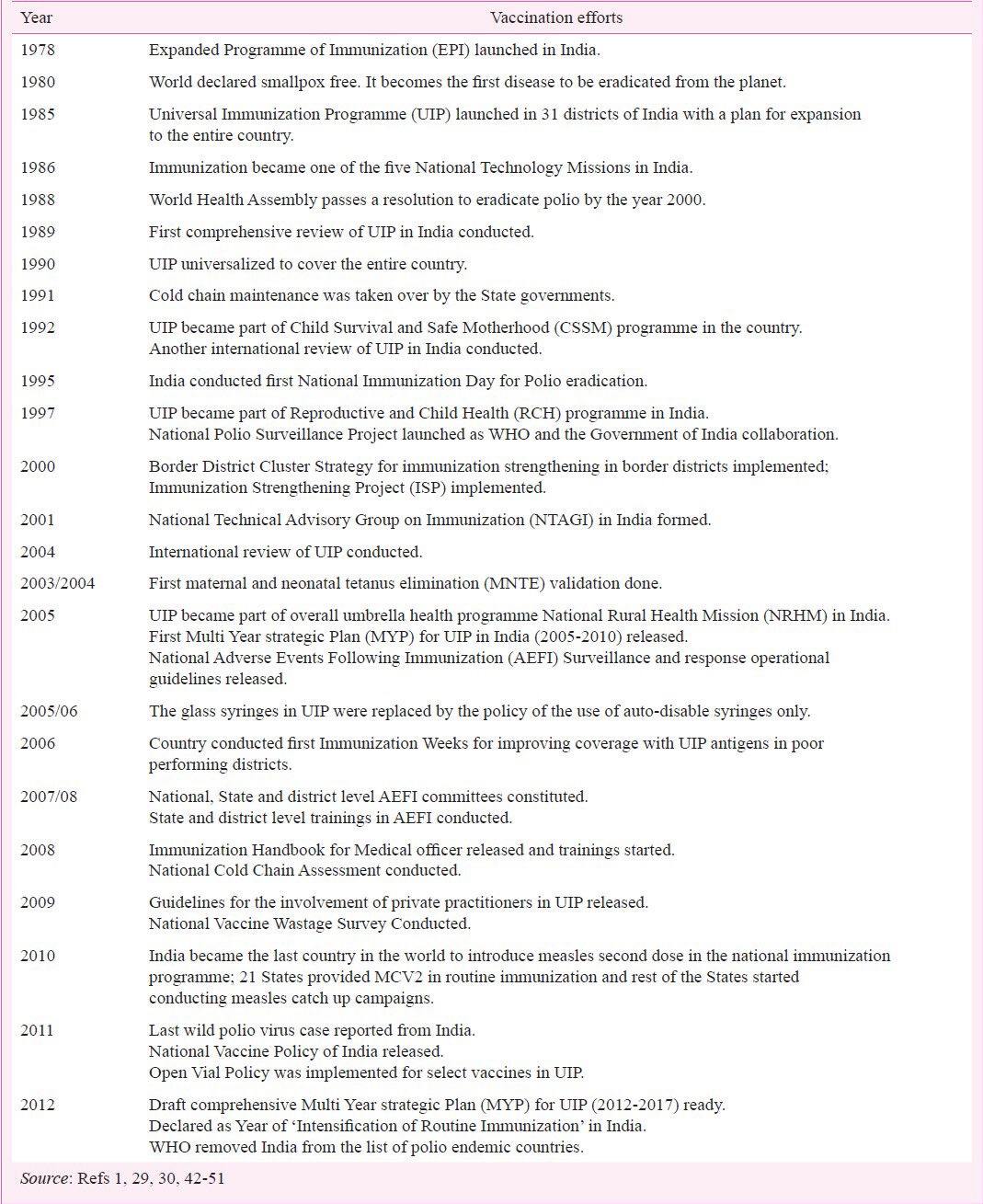

Table VI.

Major milestone since launch of EPI in India (1978- till 2012)

In 1988, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution for polio eradication by 200052. There were special state-specific efforts for control of poliomyelitis in India. Tamil Nadu state had conducted polio vaccination campaigns as part of rotary supported ‘Polio Plus’ campaign in 1985. Similarly, following WHA resolution, Tamil Nadu and Kerala states conducted State-wise polio vaccination campaigns in 1993/1994 also. Delhi state of India, conducted first state-wide polio vaccination campaign on October 2, 1994, followed by another round in December 1994. The Government of India joined global polio eradication efforts and the first two National Immunization Days (NIDs) for poliomyelitis eradication in India were conducted on December 9, 1995 and January 20, 1996. Children up to 3 yr of age were targeted in these NIDs and about 87 million children were covered. The target age group was increased to 5 years in the next year and about 125 million children were vaccinated. The government was supported by multiple international organizations and donor agencies in polio eradication efforts55.

An organized surveillance mechanism was established as National Polio Surveillance Project (NPSP) in 1997, which was a collaboration between the Government of India and the World Health Organization. The NPSP over the period of time built an institutional mechanism for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance53,54. India reported the last case of wild polio virus (type 1) on January 13, 2011 from Howrah district in West Bengal. On February 25, 2012, the World Health Organization had removed India from polio endemic countries55. In early 2014, WHO Southeast Asia Region is expected to become 4th WHO region to be certified polio free. The major milestones in India becoming Polio free are outlined in Table VII.

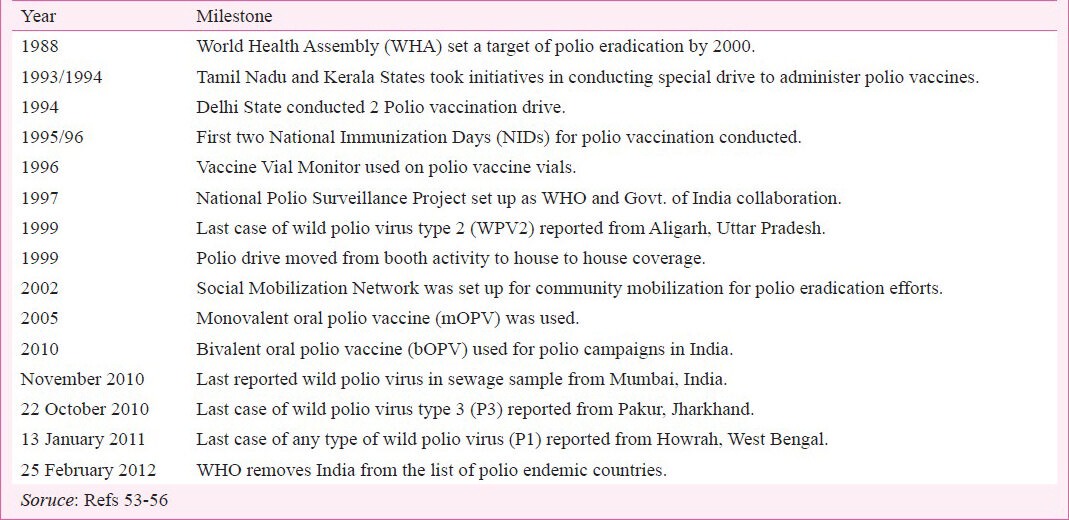

Table VII.

Timeline of polio eradication efforts in India

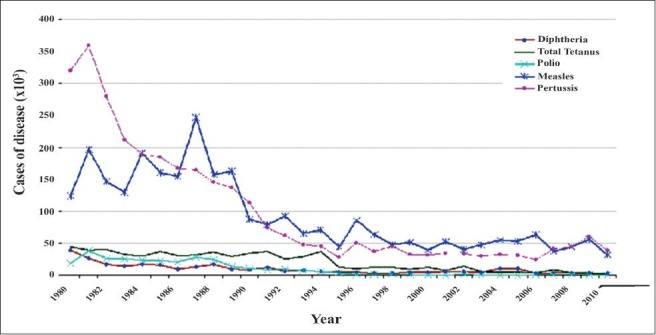

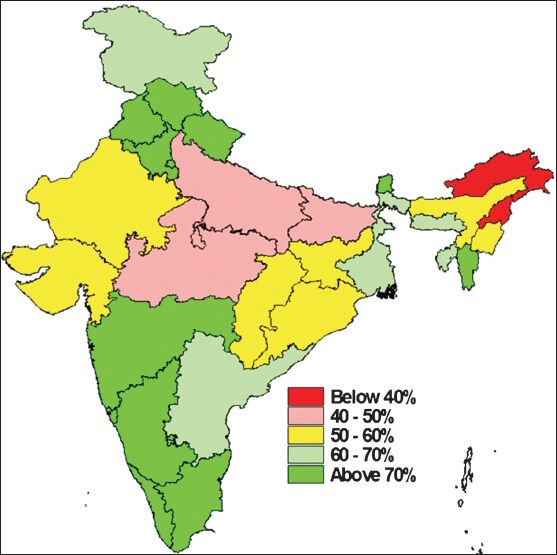

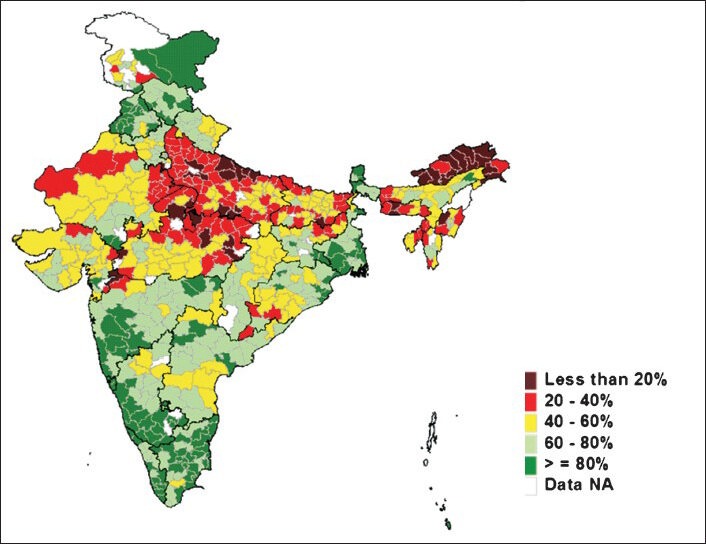

Immunization programme in India started with the aim to reduce VPDs, completed three decades in 2008. It has partially succeeded in reducing the burden of vaccine preventable diseases; however, significant proportion of VPDs still exists for the reason of suboptimal coverage with the UIP antigens. Though reported vaccination coverage is always higher, there is a wide gap in reported and evaluated coverage in India. Though the antigen wise coverage is suboptimal, the existing coverage has helped in noticeable reduction of the reported cases of VPDs in India, even with an increasingly sensitive surveillance system (Fig. 1)45,57,58. The evaluated coverage has been low, with the proportion of fully immunized children in India is still at 61 per cent, with wide state-wise, geographical, religion, rural urban and gender variations (Fig. 2)4. The situation seemed to have improved only slightly in the last few years and the district-wise coverage also showed wide variations and poor performing districts within good performing states also (Fig. 3)59.

Fig. 1.

Reported cases of major vaccine preventable diseases in India (1980-2010).

Fig. 2.

Evaluated State-wise proportion of fully immunized children in India.

Source : Ref. 4.

Fig. 3.

Evaluated full immunization coverage by district in India.

Source: Ref. 61.

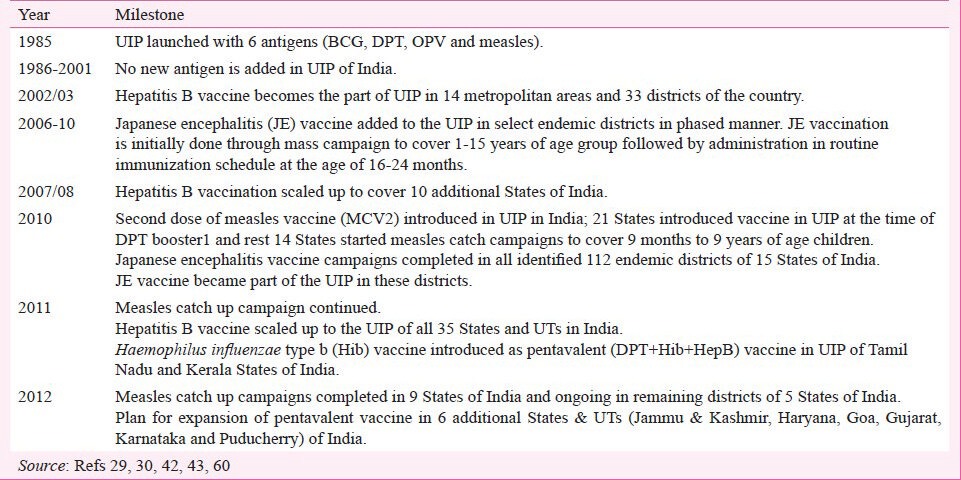

In 1985, UIP started with six antigens (BCG, OPV, DPT and measles) in the programme and no new antigen was added to the programme for the next 16 years. During this period, globally and in India, a number of new vaccines became licensed and available in the market. The first new antigen added since the beginning of UIP was hepatitis B vaccine when in the year 2002/2003, it was introduced as a pilot in selected 33 districts and 14 metropolitan areas of India42. In 2011, HepB vaccine became the 7th antigen to be introduced in the UIP across the country. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine has been introduced in Kerala and Tamil Nadu states starting December 201160. The major milestones in the introduction of new antigens in UIP in India are summarised in Table VIII.

Table VIII.

Introduction of new antigens in UIP in India

In 2010, India became the last country in the world to introduce second dose of measles vaccine in the national immunization programme. A few states have introduced vaccine in UIP at the time of second booster and the remaining 14 states through supplementary Immunization Activities (SIAs). By end of 2012, measles campaigns have been completed in 137 districts of nine states namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Jharkhand, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Tripura targeting nearly 27 million children. In five states Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat where nearly 110 million children were targeted in 230 districts, a total of 61 districts had completed campaigns vaccinating about 26 million children43 (Personal Communication: Dr Pradeep Haldar; Deputy Commissioner, Immunization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi 2012).

There have been additional national efforts to improve coverage, which include launch of Immunization Strengthening Project (ISP), Urban Measles Campaigns and that of Border Districts Cluster Strategy (BDCS), etc.30,38. Similarly, in the low performing districts the Immunization weeks were celebrated. Other important developments of this period include:

(i) The National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI) in India was constituted in 2001, and was reconstituted in 201044.

(ii) The Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI) reporting has been a part of UIP since 1985. The first documented AEFI report and guidelines were published in 1988. The reporting of AEFI in India remained poor till early 2005. The AEFI guidelines were revised and widely disseminated in 2005/2006. The reporting has slightly improved since then and now there is additional focus on conducting causality assessment for serious AEFIs61,62. There is an ongoing discussion to include private practitioners in AEFI reporting specially for post-marketing surveillance for new vaccines in India.

(iii) The efforts have been made to strengthen the post-marketing surveillance for vaccines in India. As part of licensing process and as post-marketing surveillance the manufacturers are required to submit Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) for all newly licensed vaccines to Central Drug Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), initially every six months in the first two years and then annually for next two years62. The National Pharmacovigilance Programme in India has been launched in July 201063. India has joined the WHO Global Network of Post Marketing Surveillance (PMS) for new vaccines in Maharashtra state represents India, this PMS network of 12 countries from six different regions. This network aims to provide useful data for global vaccine safety assurance43.

(iv) India adopted the policy of use of auto disable syringes only for UIP in the country starting 2005/2006. The glass syringes have been phased out from immunization programme.

(v) India adopted a policy for procuring all vaccines in UIP with Vaccine vial Monitor (VVM) to monitor potency of the vaccines in field situation. The multi dose vial policy or open vial policy (which allows the use of opened multi dose vaccine vial in subsequent sessions) in India was not applicable for routine immunization programme and was practiced in Polio campaigns only. The Government of India extended open vial policy for fixed sessions for hepatitis B birth dose and oral polio vaccine zero doses in May 2011. Subsequently, October 2011 onwards, the Open Vial Policy was extended to Hib containing pentavalent (DPT+HepBB+Hib) vaccine for outreach sessions also64.

(vi) The immunization programmes aim to achieve the goals envisaged in National Health Policy and National Population Policy of India. The first Multi Year strategic Plan (MYP) for UIP in India (2005-2010) was launched in 200529. A new ‘comprehensive Multi Year strategic Plan (MYP) for UIP in India for the period of 2012-2017 has also been drafted58.

(vii) India released the first National Vaccine Policy in 2011. The policy provides guiding principles for functioning of immunization programme in the country65.

The year 2012-2013 was declared as ‘Year of intensification of Routine Immunization (IRI) in India. There was increased focus on improving coverage in identified 239 poor performing districts in India. The government intends to focus attention and priority on conducting immunization week in these states and districts, conducting more regular review and monitoring and supervisions, improving cold chain status, and improving IEC efforts for increasing coverage for all the antigens43.

Vaccine availability and manufacturing in India (1978- till now)

There were systematic efforts to achieve self-sustainability for all vaccines in UIP in India. As part of these efforts and under the mandate of National Technology Mission on Immunization, in March 1989, two companies: The Indian Vaccines Corporation Limited (IVCOL) started in Gurgaon, Haryana, and Bharat Immunologicals and Biologicals Corporation Limited, (BIBCOL) in Bulandshahar, Uttar Pradesh, were incorporated. However, The IVCOL which was incorporated as a joint venture company to undertake research and development and manufacture of the viral vaccines, stopped functioning a few years later due to some problems and with change in product mix and technology transfer65.

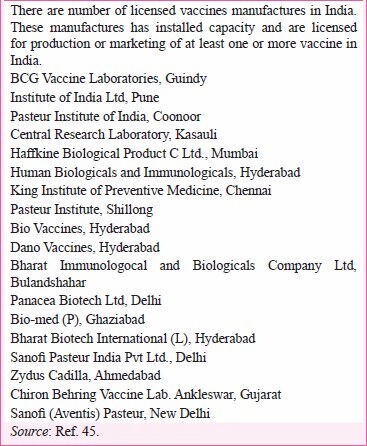

The list of manufacturers either having installed capacity or producing at least one or more vaccines is provided in the Box 145.

Box 1.

List of licensed vaccine manufacturing units in India

The setting up of vaccine manufacturing units and grant of permission of clinical trials and final licensing and marketing authorization for vaccines in India is provided by the Central Drug Standards Control Organization (CDSCO), which is a National Regulatory Authority (NRA) in the country. The regulatory control over quality of drugs in the country is exercised through the Drug and Cosmetics Act, 1940. The schedule Y of this act regulates clinical and pre-clinical testing of the products. As per the Act, vaccines and other biological products are considered to be a ‘new drug’ and thus are governed by all rules and regulations applicable to a new drug66. India is major global vaccine manufacturer and supplies vaccines to many developing countries. The World Health Organization has standard mechanism for assessing the quality of vaccines and that of manufacturing units and provides prequalification of vaccines for procurement for United Nation supply67. This WHO prequalification is considered a standard for vaccine quality. Several vaccine products from Indian vaccine manufacturers have received WHO prequalification.

The vaccine manufacturing and procedures for clinical trials have become systematic in India in recent years. In 2006, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, India released a new set of guidelines for conduct of research on human subjects46. There is a section on vaccine research and clinical trials in these guidelines and all the vaccine related trials now need to be registered in clinical trial registry and to be done in accordance with these guidelines. The capacity of Indian vaccine manufactures was put on the test when the need for vaccine against Novel H1N1:2009 arose in the wake of Pandemic alert. Three manufacturers developed pandemic flu vaccine in a short period of time47.

The last three years have brought many achievements for the Indian vaccine industry. A new bivalent oral cholera vaccine, a meningitis-A vaccine, and an indigenous Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccine were developed by Indian manufacturers in collaboration with international partners and are now licensed in India48,49,50. An injectable cholera vaccine was available and licensed in the country till 1973; however, that vaccine had efficacy of nearly 30 per cent and provided protective immunity for only 8 months48. Thus, the use of this vaccine was stopped in the country. In 2009, a new bivalent (O1 and O139) killed whole cell oral cholera vaccine was licensed for two dose schedule in India. The vaccine available at low price received WHO prequalification procurement by UN agencies48,49,50,51. The highly effective meningitis A vaccines, available at a very low cost (50 Cents per dose or ₹ 30 per dose) is one of the cheapest new vaccines available and used in nearly 100 million doses in the countries of African meningitis belt49,51.

Till 2012, the JE vaccine used in India was imported from outside country. In recent years, the Department of Biotechnology, Department of Science and Technology (DST), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and Institutes such as National Institute of Immunology, All India Institute of Cholera and other Enteric Diseases, and All India Institute of Medical Sciences have started playing crucial, complimentary and collaborative role in vaccine research and providing the needful impetus to the indigenous vaccine development65.

For long, only available typhoid vaccine in India was Vi Polysaccharide vaccine. A new conjugate typhoid vaccine produced by Indian manufacturer was licensed in the country in 2008/200968. However, a few questions about the efficacy trials of this vaccines and usage have been raised and it is not recommended by many professional bodies. The Government of India had suspended the license of a few vaccine manufacturing units in public sector in 2008. The suspension of licences of the three public sector vaccine manufacturing units viz. Central Research Institute (CRI), Kasauli, Pasteur Institute of India, Coonoor and BCG Vaccine Laboratory, Guindy, was revoked in February 2010 enabling them to resume production in the larger public interest of vaccine security in the country56.

There is indigenous production capacity for all (except JE) vaccines in National Immunization programme in India. The production capacity for other licensed vaccines is also available except a few such as Rotavirus vaccines, Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccines, which are not produced in the country. Live attenuated Oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a and (WC-rBS) and whole cell Oral cholera (O1 with recombinant cholera toxin B subunit) vaccine are amongst a few vaccines which are not licensed for use in India63.

An indigenous rotavirus vaccine was undergoing research and trial in India69 and in May, 2013 the findings of phase III clinical trial of an indigenously researched rotavirus vaccine, based on an indigenous strain called 116E were announced. The vaccine, named ROTAVAC, trial covered nearly 6800 infants, the ratio of vaccine to placebo being 2:1 (4532 were administered the vaccine and 2267 placebo). The assessed efficacy and safety profile of the vaccine were reported to be comparable to those of other licensed and available rotavirus vaccines. The findings of this trial were subsequently published in 201470. The development and successful completion of clinical trial of ROTAVAC is being considered a major milestone, and an example of successful ‘public–private partnership’ and a ‘unique social innovation model’71. The indigenous production of a new vaccine in India has always had an effect on the availability of the vaccine, not only in the country but globally as well. The Indian rotavirus vaccine is likely to be made available at a cost of US$ 1 per dose (comparing to currently available rotavirus vaccines cost around US$ 4 to upto 50 per dose) and can be stored at freezing temperature, factors which contribute to further lowering the costs of the immunization programme.

In August 2013, a typhoid conjugate vaccine, Typbar-TCV (a fourth-generation vaccine against typhoid disease), was launched in India72. In September 2013, the indigenous Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccine, JENVAV, was licensed in India. This JE vaccine was jointly developed by the scientists from the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune, (Indian Council of Medical Research) and Bharat Biotech Ltd73.

Vaccination programme and vaccines in India: Years ahead

The science of vaccine evolved across the globe in late 19th century and India was amongst a few countries to have been involved in these efforts. The cholera and typhoid vaccine trials and research and discovery of plague vaccine took place in the country. Vaccine institutes were set up in early and whole of twentieth century. Though the pattern moved from public to private vaccine manufacturing units but the country has retained self-sufficiency through indigenous production. Smallpox has been eradicated and the country has become poliomyelitis free since January 2011.

In spite of all positive changes, there are ongoing challenges and shortcoming in the programme. The coverage with vaccines in National Immunization Programme is suboptimal and only 3/5th children receive all due vaccines and only 3/4th receive 3 doses of DPT vaccine4. There are inter- and intra-state variations in the coverage59. Data recording and reporting is sub-optimal and disease surveillance system desires a lot for improvement. The lack of supervision and monitoring is often cited and communication for increasing immunization coverage is limited. The system for AEFI surveillance is improving but still need to be strengthened58. There have been systematic efforts in the last decade to show a hope that immunization coverage would be improved in coming months and years.

The history of vaccination efforts suggests that the systematic methodological rigour is required to improve coverage with all antigens in a diverse country like India, with health being state subject. The methodological rigour of past and focus on research has a lot to guide immunization programme in India. Some of the key common areas in early vaccination efforts and current times are as follows : (i) Smallpox control efforts focused both on hygiene and sanitation measures and vaccination. This approach has to be followed for many new antigens such as Rotavirus diarrhoea etc.; (ii) There was strong opposition of vaccination by a section of experts and society. These groups derived strength from similar groups in other countries. Though time has changed, the similar groups exist in the present times, (iii) Limited and incomplete reporting of smallpox cases and deaths (disease surveillance) failed the programme managers to prove that vaccination is making any significant change. The disease surveillance scenario poses similar challenges in the current times.

The programme has become more complicated with addition of new antigens and disappearing diseases (as a result of improved coverage) has raised people's expectations on the safety standards of the vaccines. During this period, stringent safety regulation has made vaccine research costly with more sophisticated technique. These factors have led to reduction in the number of vaccine manufacturers in both public and private sectors.

A major challenge in vaccine production in India is sub-optimal investment by public sector for vaccine research. The vaccine manufacturing units set in India are still producing some of the traditional vaccines and there appears to be a need for more funding and research on newer antigens. Indian manufacturers are participating in the development and clinical trials of a number of other candidate vaccines which would ensure that these vaccines are accessible to Indian population, as and when these become available56. The national vaccine policy of India has suggested that ‘a number of linkages need to be explored between academia, industry and international institutions such as National Institute of Health (NIH), Gates Foundation, the GAVI Alliance, PATH, World Health Organization and the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), etc65.

Immunization programme needs better support and funding for conducting operational research to address programmatic issues and to improve coverage with all antigens in UIP of India. There is increasing demand for additional antigens such as mumps, rubella, and typhoid vaccine in India. The immunization programme in India is a centrally funded programme. A good proportion of children are vaccinated with available and licensed non UIP antigens. Increasing proportion of immunization is being provided by private sector and the proportion is likely to increase over coming years. The benefits of vaccination need to be extended beyond traditional childhood period and new approach of ‘life-course immunization’ for including larger age groups such as adolescent and elderly is being contemplated globally, with an argument that not offering the benefits of available safe and effective vaccines is an ethical issue14. The national technical bodies need to deliberate and come up with its advice and opinion. This would change the dynamics and government may not be able to finance all vaccination efforts and there would be increasing role of professional association in supporting vaccination efforts of the country. This highlights the futuristic need for better and regular interactions in government programme managers and professional bodies to shape the vaccination efforts in the country.

The systematic efforts are needed to generate evidence for making a decision to (or not to) introduce new antigens in the programme and to prove the impact of vaccine introduction on disease, once the vaccine is introduced. There have been discussions for strengthening VPD surveillance in the country since the beginning of UIP; however, surveillance for VPDs is far from optimal. The discussion should be moved from implementation and a robust VPD surveillance system, encompassing all existing and upcoming antigens, should be developed with ability to provide sufficiently representative data from all parts of the country.

Implementing immunization programme cannot be segregated from the ‘knowledge-base’ in immunology. The number of trained people in vaccinology and immunology in India is less than what country of this size requires. Globally, the practice of immunology has slowly become part of vaccinology; however, in India there is still limited focus on training in vaccinology and immunology. The technologies for ensuring efficient and potent vaccines to the beneficiaries are becoming available and should be optimally utilized.

Conclusions

The evolution of vaccination efforts in India is far more complex than presented in this review and every single event merits a detailed analysis. Though preventive efforts from diseases were practiced in India, the reluctance, opposition and slow acceptance of vaccination have been the characteristic of vaccination history. The operational challenges keep the coverage inequitable in the country. The lessons from the past events have been analysed and interpreted to guide immunization efforts. There are many lessons learnt from the history from extending the benefits of immunization to every possible beneficiary in the country to achieve the stated policy goals.

Acknowledgment

A part of this work was done when the author was a faculty member at GR Medical College, Gwalior, India. The work was completed when he was a trainee fellow at immunology and vaccinology course at Institute Pasteur, Paris, France.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this paper are solely attributable to the author and should not be attributed to any institution/organization he has been affiliated in the past or at present.

References

- 1.3nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2009. World Health Organization ganization (WHO) Unicef, World Bank. State of the world's vaccines and immunization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: WHO; 2012. Mar, [accessed on May 30, 2012]. World Health Organization. Global immunization data 2011. Available from: www.who.int/hpvcentre/Global_Immunization_Data.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi ID. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1988. Smallpox and its eradication; pp. 369–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Delhi: Government of India and UNICEF; 2010. United Nations International Children's Fund. Coverage evaluation survey: all India report 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu RN, Jezek Z, Ward NA. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization, South-East Asia Regional Office; 1979. The eradication of smallpox from India. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharya S, Harrison M, Worboys M. Hyderabad: Orient Longman; 2006. Fractured states: Smallpox, public health and vaccination policy in British India, 1800-1947. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazin H. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. The eradication of smallpox: Edward Jenner and the first and only eradication of a human infectious disease. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brimnes N. Variolation, vaccination and popular resistance in early colonial south India. Med Hist. 2004;48:199–228. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowdle WR. The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(Suppl 2):22–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitchett JR, Heymann DL. Smallpox vaccination and opposition by anti-vaccination societies in 19 th century Britain. Hist Med. 1995;2:E17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of small pox and vaccination. BUMC Proc. 2005;18:21–5. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The history of vaccines. [accessed on March 16, 2012]. Available from: http://www.historyofvaccines.org .

- 13.Holwell JZ. London: Printed for T Becket and PA de Hondt; 1767. An account of the manner of inoculating for the smallpox in the East Indies: with some observations on the prctice and mode of treating that disease in those parts. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wujastyk D. A pious fraud: the Indian claims for pre-Jennerian smallpox vaccination. In: Jan Meulenbeld G, Wujastyk D, editors. Studies on Indian medical history. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers; 2001. pp. 121–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharya S, Jackson M. London: Wellcome Institute; 2005. Vaccination against smallpox in India. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A. New Delhi (India): Sage Publications; 1998. Medicine and the Raj: British medical policy in India, 1835-1911. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu RN. Smallpox eradication: lessons learnt from a success story. Natl Med J India. 2006;19:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smallpox eradication. Swasth Hind. 1963;7:249–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smallpox zero. Swasth Hind. 1976;20:198–226. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattacharya S. New Delhi: Orient Longman; 2006. Expunging variola: the control and eradication of smallpox in India, 1947-77; pp. 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazin H. Paris, France: John Libbey Eurotext; 2011. Vaccination: history from Lady Montagu to genetic engineering; pp. 110–245. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haffkine Institute webpage. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: www.haffkineinstitute.org/

- 23.Wikipedia Haffkine Institute. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haffkine-Institute .

- 24.Greenwood M, Yule GU. The statistics of anti-typhoid and anti-cholera inoculations, and the interpretation of such statistics in general. Proc R Soc Med. 1915;8:113–94. doi: 10.1177/003591571500801433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cockburn WC. Large-scale field trials of active immunizing agents, with special reference to vaccination against pertussis. Bull World Health Organ. 1955;13:395–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cvjetanovic BB. Field trials of typhoid vaccines. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1955;47:578–81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.47.5.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.New Delhi: The Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 1996. Annual report of MoHFW 1995-96. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasteur Institute of India, Coonoor, Nilgiris. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.pasteurinstituteindia.com .

- 29.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2005. Government of India. Multi Year Strategic Plan for Universal Immunization Program in India (2005-2010) [Google Scholar]

- 30.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. Government of India. Report of National Universal Immunization Program review 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madras: Tamil Nadu State Archive, Health Department, no. 809; 1950. Undated press note (but the note is accompanied by a covering letter dated 28 May 1948) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Central TB Division. Tuberculosis Control India. Directorate General of Health Services. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.tbcindia.nic.in/history.html .

- 33.Brimnes N. Vikings against tuberculosis: the International Tuberculosis Campaign in India 1948-1951. Bull Hist Med. 2007;81:407–30. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahler HT, Mohamed Ali P. Review of mass B.C.G. project in India. Indian J Tuberc. 1955;2:108–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhushan K. Assessment of BCG vaccination in India: third report. Indian J Med Res. 1960;48:407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.No authors listed. Tuberculosis Research Centre. Fifteen year follow up of trial of BCG vaccines in south India for tuberculosis prevention. Indian J Med Res. 1999;110:56–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.New Delhi: The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 1965-2010. Government of India. Annual reports of Government of India 1965-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 1986. Government of India. Circular of Government of India on National Technology Mission. [Google Scholar]

- 39.UNICEF. Child health. Goals for children and development in the 1990s. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/wsc/goals.htm#Child .

- 40.UNICEF. World declaration on the Survival production and development of children: the challenge. World summit for Children. 1990. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/wsc/declare.htm#Thechallenge .

- 41.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 1992. Annual Report of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 1991-92. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lahariya C, Subramanya BP, Sosler S. An assessment of hepatitis B vaccine introduction in India: lessons for roll out and scale up of new vaccines in immunization programmes. Indian J Public Health. 2013;57:8–14. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.111357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2012. Jul, Government of India. National Review meeting of State Immunization officers. [Google Scholar]

- 44.John TJ. India's National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization. Vaccine. 2010;28(Suppl 1):A88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.New Delhi: CBHI, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2012. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. National Health Profile of India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.New Delhi: ICMR: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2006. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants; pp. 11–90. Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goel MK, Goel M, Khanna P, Mittal K. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccine: an update. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:13–8. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.76517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. Inactivated oral cholera. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/pq_250_cholera_1dose_shantha/en/index.html .

- 49.Meningitis Vaccine Project. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.meningvax.org/

- 50.Somasekhar M. Hyderabad: 2012. [accessed on October 30, 2012]. Biological E launch vaccine to treat Japanese encephalitis. September 13. Available from: http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/article3892518.ece . [Google Scholar]

- 51.Program for Appropriate Technology for Health (PATH). 100 millionth person receives life saving meningitis. A vaccine. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://www.path.org/news/pr121203-menafrivac.php .

- 52.Lahariya C. Global eradication of polio: case for “finishing the job”. Bull World Helath Organ. 2007;85:487–92. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.037457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.New Delhi: MoHFW; 2012. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Polio eradication in India. [Google Scholar]

- 54.The National Polio Surveillance Project. A Government of India-WHO Colloboration. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: www.npspindia.org .

- 55.World Health Organization. India records one 55. year without polio cases. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2012/polio_20120113/en/index.html .

- 56.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2010. Sep, Government of India. Annual Report to the People on Health 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Annual reported vaccine preventable disease data. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and family Welfare, Government of India; 2011. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- 58.New Delhi: MoHFW; 2012. Government of India. Comprehensive Multi Year Plan for immunization in India (2012-2017) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Government of India, New Delhi: IIPS, Mumbai and ORC Macro and MoHFW; 2009. International Institute for Population Studies. District Level Household Survey (2007-08)- 3. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gupta SK, Sosler S, Lahariya C. Introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) as pentavalent (DPT-HepB-Hib) vaccine in two States of India. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:707–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2010. Govt. of India. Adverse Events following Immunization surveillance and response operational guidelines, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chitkara AJ, Thacker N, Vashishtha VM, Bansal CP, Gupta SG. Adverse event following immunization (AEFI) surveillance in India, position paper of Indian Academy of Pediatrics, 2013. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:739–41. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. National Pharmacovigilance Programme of India. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/pharmacovigilance_intro.htm .

- 64.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2011. Government of India. The guidelines for use of open vial policy in Universal Immunization Program of India. May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2011. Government of India. National vaccine policy. [Google Scholar]

- 66.New Delhi: Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Central Drugs Standards Control Organization. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/ [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geneva: WHO; 2012. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. World Health Organization. A system for the prequalification of vaccines for UN supply. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/pq_system/en/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 68.BioMed India. Vi conjugate typhoid vaccine. [accessed on May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/article3892518.ece .

- 69.New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2008. National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (NTAGI). Subcommittee on Rotavirus vaccine. Minutes of meeting of August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhandari N, Rongsen-Chandola T, Bavdekar A, John J, Antony K, Taneja S, et al. for the India Rotavirus Vaccine Group. Efficacy of a monovalent human-bovine (116E) rotavirus vaccine in Indian infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 Mar 11; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62630-6. pii: S0140-6736(13)62630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhan MK, Glass RI, Ella KM, Bhandari N, Boslego J, Greenberg HB, et al. Team science and the creation of a novel rotavirus vaccine in India: a new framework for vaccine development. Lancet. 2014. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/101016/S0140-6736(14)60191-4 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Pilla V. Delhi: Mint; 2013. Aug 27, Typhoid vaccine with longer immunity launched; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 73.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2014. Oct 4, [accessed on April 10, 2014]. Govt. of India. Press release from Press Information Bureau: Shri Ghulam Nabi Azad launches JE Vaccine (JENVAC) produced by NIV, ICMR and Bharat Biotech. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=99873 . [Google Scholar]