Abstract

Background & objectives:

After menopause in women, loss of bone density increases rapidly with estrogen deficiency. Evidence has revealed that this deficiency may be directly correlated with growth hormone (GH) level declining with age. The present study was designed to evaluate the age dependant patterns of GH, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1-1) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) endogenous secretion in postmenopausal women.

Methods:

During this prospective study in a 12-month period, 150 postmenopausal women were enrolled who were referred to the densitometry unit of bone research centre of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for assessing bone mineral density. Serum levels of basal and clonidine stimulated GH were measured using radioimmunoassay while IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 were measured by ELISA. Post stimulation over 3 to 6 fold increase in GH over the baseline level was considered normal response and less increase was considered abnormal.

Results:

There were no significant differences in the mean levels of GH0, GH60 and GH90 in different age groups of postmenopausal women. No significant difference in the mean IGFBP-3 and IGF-1 levels was seen in different age groups of postmenopausal women. The number of postmenopausal women with abnormal response to stimulation by clonidine in 61-70 and > 70 yr age groups was higher than in other groups (P< 0.05).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Despite the higher rate of abnormal response to stimulation by clonidine in women aged more than 60 yr, the current study showed no significant correlation between age, and the basal and stimulated GH secretion rate and serum levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in postmenopausal women.

Keywords: Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, postmenopausal women

During menopausal period, gradual loss of function occurs in hormone secretion and metabolism. The periodic secretion of estrogen and progesterone by ovaries decreases, and finally, ovaries lose their periodic activity1,2,3. Most of the postmenopausal women sustain some symptoms which are related to estrogen insufficiency independent of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels. These symptoms might not be directly associated with estrogen insufficiency, but might be multi-factorial or related to senile process4,5. These symptoms vary from short-term simple irritations to long-term serious problems. Before menopause, the reduction rate of bone mineral mass is less than 1 per cent but it reaches to 5 per cent per year after this period. According to the previous reports, this reduction might be related to a gradual decrease of growth hormone (GH), which is age-dependent6,7,8. Menopause causes a cascade of events in the physiology of body which is not well recognized, so investigating the relation between GH, IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in post menopausal women may clarify this process.

The present study was designed to evaluate the pattern of GH, IGF1-1 and IGFBP-3 endogenous secretion in postmenopausal women, based on women's age.

Material & Methods

The present prospective study was conducted at Tabriz Sina Medical-Educational Center, Tabriz, Iran, from February 2008 to February 2009. One hundred and fifty postmenopausal women fulfilling the inclusion criteria were enrolled consecutively into the study from 1243 women who referred for bone densitometry during this period.

Women were included based on densitometry results and World Health Organization's criteria9,10. To study age dependant patterns of GH, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3, women were divided into ≤ 50, 51-60, 61-70, and ≥ 71 yr old groups.

All participants signed a written consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran.

Age, weight, and height were measured and formal physical examination was performed. Demographic details and information on nutritional condition and medical history were collected from these women. These women had their menopause at least two years before and had not used any kind of estrogen derived products for the last six months. These women were healthy, did not smoke, were not alcohol consumer or in any medical procedure, and had normal renal, hepatic and thyroidal functions.

Women who had a positive history of drug use with effects on bone mineral density (BMD), GH, IGF-I, or IGFBP3, were excluded. These drugs include corticosteroids, heparin, levothyroxine, lithium, anticonvulsants, long acting growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) analogues, cyclosporine, chemotherapeutic agents, aluminum containing antacids, (continuous use for over 1 year) and estrogen (as medications affecting BMD); levodopa, clonidine, bromocriptine, propranolol, H2 receptor antagonists, and cholinergic agonists (as GH stimulating agents); somatostatin, phentolamine, yohimbine, phenothiazines, cyproheptadine, methysergide, isoproterenol and glucocorticoids (as GH suppressing agents).

Venous blood samples (5 ml) were obtained following an overnight fasting state and were collected in empty sterile tubes, and immediately stored in ice at 4°C. The serum was separated and was divided in two parts. One part was stored as such and another was stored in EDTA microtube at -25°C until analysis.

The basal fasting levels of GH, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 level were measured in all enrolled subjects. Clonidine stimulation test was carried out after consumption of 0.04 μg/kg clonidine and measuring repeated GH levels at 60 and 90 min. Post stimulation 3 to 6 fold increase over base-line level in GH was considered normal response and less than 3 fold increase was considered abnormal11.

GH was measured by radioimmunoassay method12 (Kavoshyar TM, Iran). The inter- and intra-observational coefficients of variation were 2.8 and 4.2 per cent, respectively. IGF-I and IGFBP-3 were measured by ELISA (Biosource TM, Belgium). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients for variations of the measurements were 5.5-10.1 and 6.2-9.7 per cent, respectively. All laboratory studies were performed at the Plasma Medical Laboratory, Tabriz, Iran.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software package version 16.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while qualitative data are given as frequency and per cent. Normal distribution of data was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since height, weight, GH-90, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels distributions were normal, one way ANOVA test was used to compare groups. However, repeated measurements of ANOVA was used to compare the basal GH (GH-0) and GH-60 levels in difference groups. Linear correlations were evaluated by Pearson's correlation coefficient and linear regression model. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

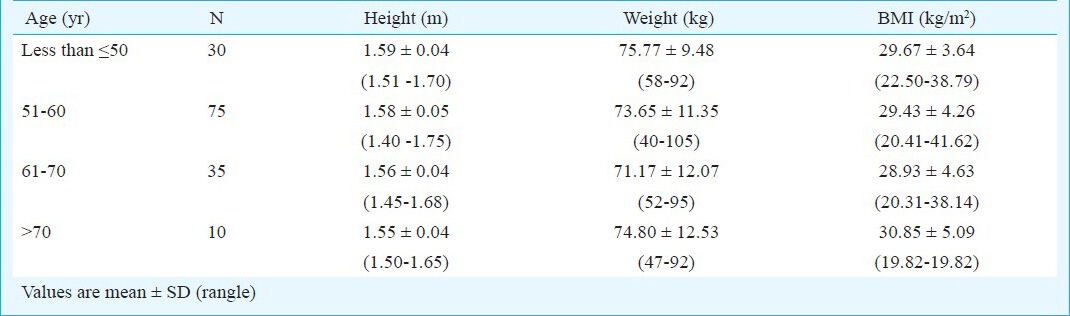

The women had mean age 57.7±7.5 yr, mean weight 73.6±11.3 kg. The mean and mean height 1.58±0.05m. BMI was 29.5±19.8 kg/m2 (range 49.8 – 41.6). In this study, 75 women (50%) were 50-60 yr old. According to the WHO classification, only 25 women (17%) had normal weight and BMI (18-24.9 kg/m2)13. Mean height, weight and BMI in different age groups were not significantly (Table I).

Table I.

Height, weight and BMI of women in different age groups

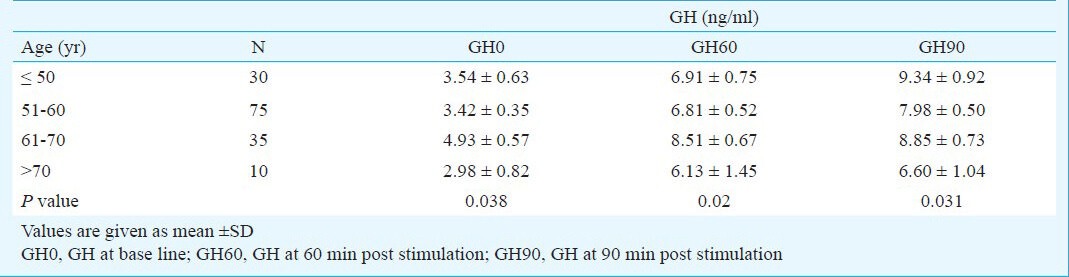

GH concentration increased post stimulation at 60 and 90 min (P< 0.05), but the increase was not significant between groups (Table II).

Table II.

Grows hormone concentration changes in base of age groups

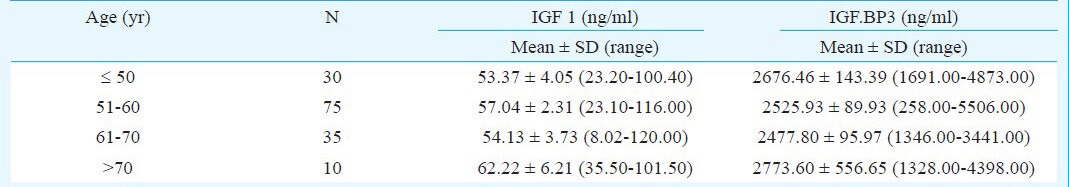

Pearson's correlation coefficient failed to show any significant correlation between IGF1 and IGF BP3 with age (r=0.09, P=0.25 and r=0.21, P=0.21, respectively). Mean IGF1 and IGF BP3 concentrations in > 70 yr age group were the highest among other age groups. Comparison of mean IGF1 and IGF BP3 concentrations in different age groups did not show significant difference (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison of mean insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) concentrations in post menopausal women in different age groups

In order to control the confounding factors, variables which were significantly related to patients’ age were entered into linear regression model. After controlling effect of confounding factors, linear regression model indicated that patients’ age as a predicting factor did not correlate with IGF1 and IGFBP3. There was no significant correlation between IGF level in different age groups according to the stratified analysis.

In group ≤ 50 yr, 43 per cent of responses of growth hormone to the stimulation by clonidine were abnormal and 56 per cent were normal. In 51-60 yr age group 53 per cent women had abnormal responses. In 61-70 yr age group 74 per cent women had abnormal responses, while in women aged more than 70 yr, 60 per cent of responses were abnormal. Frequency of abnormal GH responses after stimulating by clonidine in 61-70 yr old group and group of > 70 yr old, was significantly higher than in other groups (P< 0.05).

Discussion

The results of the present study did not show a significant relationship between age, the basal stimulated GH secretion rate, and the serum levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in postmenopausal women. However, the frequency of abnormal response to stimulation by clonidine was higher in women aged 61-70 yr and older than 70 yr.

The relation of bone density with the levels of GH, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 has been reported earlier14,15. Changes occurred in body structures with ageing. GH secretary rate was inversely correlated with age. Various studies14,15 have shown that the reduction in adults bone mineral content correlated with GH deficiency. At the same time prescription of this hormone reverses the trend16,17,18. Estrogen plays an important role in regulating the GH secretion. It has been reported that these steroid hormones have various effects on the ratios of GH and IGF-1 and depends on the administering pathways of estrogens that probably affect the secretion of hepatic IGF-119.

Prescription of oral estrogens to postmenopausal women decreases IGF-1 and increases GH level but transdermal prescription increases level of IGF-1 without significant changes in the level of GH20,21. Sexual steroid hormones may be an important biological signal for the onset of puberty and the changes in GH situation and body fat distribution22,23.

In this study, the number of abnormal responses to clonidine stimulation in 61-70 and over 70 yr old groups was significantly more than in patients who were in 51-60 and under 50 yr age groups. It may be possible that the level of GH secretion is reduced by ageing as shown in other studies24.

In this study, we compared the levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in postmenopausal women. There was no significant difference between the mean levels of these two variables in various age groups. Karasik et al25 achieved similar results in his study. Martini et al24 showed no significant correlation between serum IGFBP-3 levels in postmenopausal women. Several studies showed that the IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels decreased significantly with age26,27,28.

In the present study, there was no significant difference between the mean levels of GH 0 (basal GH), GH-60 (GH level 60 min after stimulation with clonidine), GH 90 (GH level 90 min after stimulation with clonidine), IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1), and IGFBP-3 (insulin-like growth factor binding protein) in postmenopausal women of various age groups. The reason for the different results of this study in comparison with other studies was the less number of patients over 70 yr old.

In conclusion, the present study showed no significant correlation between age, and the bosal and clonidine stimulated GH secretion rate and serum levels of IGF-1 and IGF BP-3 in postmenopausal women.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Medical Philosophy and History Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

References

- 1.Burger HG, Dudley EC, Robertson DM, Dennerstein L. Hormonal changes in the menopause transition. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:257–75. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale GE, Burger HG. Hormonal changes and biomarkers in late reproductive age, menopausal transition and menopause. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:7–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harinarayan CV. Thyroid bone disease. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:9–11. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.93417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnet E, Lacut K, Roudaut N, Mottier D, Kerlan V, Oger E. Effects of the route of oestrogen administration on IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in healthy postmenopausal women: results from a randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:626–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subramani T, Sakkarai A, Senthilkumar K, Periasamy S, Abraham G, Rao S. Expression of insulin like growth factor binding protein-5 in drug induced human gingival overgrowth. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durica S. Use of estrogen-replacement therapy in menopause- secondary prevention of osteoporosis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2007;64:37–44. doi: 10.2298/vsp0701037d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higuchi T, Mizunuma H. Daily practice using the guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Recent evidence of estrogen therapy for osteoporosis. Clin Calcium. 2008;18:1141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho KK, Weissberger AJ. Impact of short-term estrogen administration on growth hormone secretion and action: distinct route-dependent effects on connective and bone tissue metabolism. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:821–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1137–41. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, Kendler DL, Hans DB, Lewiecki EM, et al. Official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muster L, Zangen DH, Nesher R, Hirsch HJ, Muster Z, Gillis D. Arginine and clonidine stimulation tests for growth hormone deficiency revisited--do we really need so many samples? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:215–23. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohkam M, Shamsian BS, Gharib A, Nariman S, Arzanian MT. Early markers of renal dysfunction in patients with beta-thalassemia major. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:971–6. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0753-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO EC. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aliasgharzadeh A, Bahrami A, Najafipoor F, Astanei A, Niafar M, Aghamohammadzadeh N, et al. Relation between secretory status of growth hormone, serum concentration of insulin-like growth factor I, and insulin-like growth gactor binding protein 3 with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2008;2:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pass C, MacRae VE, Ahmed SF, Farquharson C. Inflammatory cytokines and the GH/IGF-I axis: novel actions on bone growth. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:119–27. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bing-You RG, Denis MC, Rosen CJ. Low bone mineral density in adults with previous hypothalamic-pituitary tumors: correlations with serum growth hormone responses to GH-releasing hormone, insulin-like growth factor I, and IGF binding protein 3. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:183–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00298715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Froesch ER, Hussain MA, Schmid C, Zapf J. Insulin-like growth factor I: physiology, metabolic effects and clinical uses. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1996;12:195–215. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0895(199610)12:3<195::AID-DMR164>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valimaki MJ, Salmela PI, Salmi J, Viikari J, Kataja M, Turunen H, et al. Effects of 42 months of GH treatment on bone mineral density and bone turnover in GH-deficient adults. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;140:545–54. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1400545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt RI, Crossey PA, Jones JS, Baker AJ, Portmann B, Miell JP. Hepatic growth hormone receptor, insulin-like growth factor I, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein messenger RNA expression in pediatric liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1600–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho KK, O’Sullivan AJ, Wolthers T, Leung KC. Metabolic effects of oestrogens: impact of the route of administration. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2003;64:170–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly JJ, Rajkovic IA, O’Sullivan AJ, Sernia C, Ho KK. Effects of different oral oestrogen formulations on insulin-like growth factor-I, growth hormone and growth hormone binding protein in post-menopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;39:561–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roemmich JN, Clark PA, Lusk M, Friel A, Weltman A, Epstein LH, et al. Pubertal alterations in growth and body composition. VI. Pubertal insulin resistance: relation to adiposity, body fat distribution and hormone release. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:701–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roemmich JN, Rogol AD. Hormonal changes during puberty and their relationship to fat distribution. Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11:209–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1999)11:2<209::AID-AJHB9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martini G, Valenti R, Giovani S, Franci B, Campagna S, Nuti R. Influence of insulin-like growth factor-1 and leptin on bone mass in healthy postmenopausal women. Bone. 2001;28:113–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karasik D, Rosen CJ, Hannan MT, Broe KE, Dawson-Hughes B, Gagnon DR, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 4 and 5 and bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71:323–8. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin S, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Khosla S. A potentially deleterious role of IGFBP-2 on bone density in aging men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1075–83. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillberg P, Olofsson H, Mallmin H, Blum WF, Ljunghall S, Nilsson AG. Bone mineral density in femoral neck is positively correlated to circulating insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-3 in Swedish men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;70:22–9. doi: 10.1007/s002230020048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimoto T, Nakaoka D, Nasu M, Kanzawa M, Sugishita T, Chihara K. Age-dependent changes in body composition in postmenopausal Japanese women: relationship to growth hormone secretion as well as serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:633–9. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]