Abstract

Background & objectives:

Information on predictors of quitting behaviour in adult tobacco users is scarce in Indian context. Hence, this study was undertaken to assess the intention of tobacco-users towards quitting and its predictors with reference to nicotine dependence.

Methods:

A community-based observational, cross-sectional study was conducted on 128 adult tobacco-users (89.8% male) with mean age of 41.1 ± 15.7 yr selected by complete enumeration method. Data were collected by interview using pre-designed, pre-tested schedule. Nicotine dependence was assessed by Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) questionnaire.

Result:

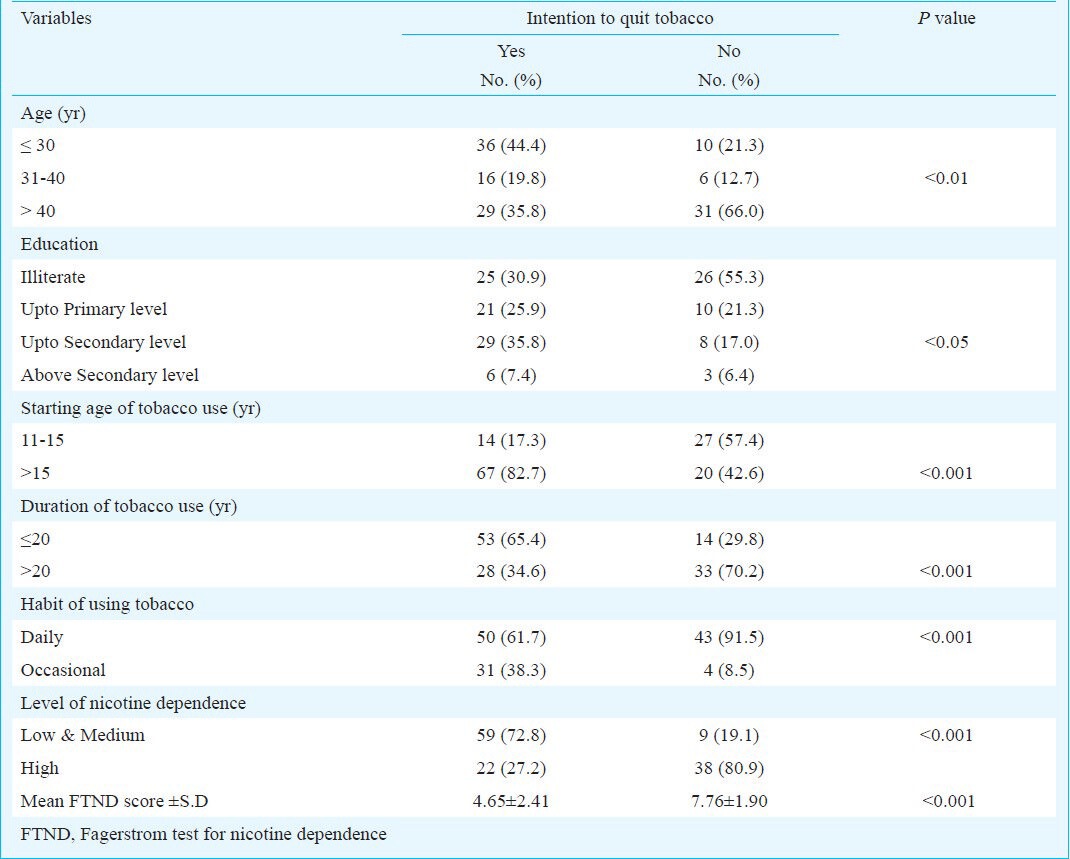

Of the 128 users, 63.3 per cent had intention to quit. Majority of the tobacco users who did not intend to quit belonged to the age group of >40 yr (66.0%), were illiterate (55.3%), started tobacco use at 11 – 15 yr of age (57.4%), had been using tobacco for 20 yr or more (70.2%), were daily tobacco users (91.5%), and highly dependent on nicotine (80.9%). Tobacco users having high FTND score and who started tobacco use early in life were 1.83 and 3.30 times more unintended to quit, respectively.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Suitable plan for quitting should be developed depending on the FTND score of an individual, the most important determinant of quitting that would be beneficial for categorization of the treatment leading to successful quitting.

Keywords: Fagerström test, FTND score, nicotine dependence, quitting tobacco

Excessive use of tobacco, also known as “the brown plague” is an example of modern epidemic1. Tobacco is the single most preventable cause of death and disability. The World Health Organization estimates that every 6 seconds somebody dies from a tobacco related disease globally2. Tobacco will cause one billion deaths in the 21st century, 80 per cent of which will occur in developing countries3. Different studies identified age, sex, ethnicity, education age at initiation of smoking and nicotine dependence as important predictors of quitting4,5,6,7. Nicotine dependence (tobacco dependence) is an addiction to tobacco products caused by the nicotine altering the mesolimbic pathway and causing temporarily mood-altering effects in brain8. Fagerström test for nicotine dependence questionnaire is an instrument that can determine the level of nicotine dependence9,10.

Though many studies have been carried out in our country on prevalence of tobacco use and its different correlates, but detailed information on the predictors of quitting habit among the users and specially the relationship of nicotine dependence with intention to quit is relatively scarce. This cross-sectional study was conducted to find out the intention of adult tobacco users (18 yr and above) towards quitting and its predictors especially in relation to nicotine dependence in an urban slum of Burdwan District, West Bengal, India.

Material & Methods

A community-based, observational, cross-sectional study was conducted in a slum - Alamganj, urban field practice area of the department of Community Medicine, Burdwan Medical College, Burdwan, West Bengal, India, during January to October 2012. Of the total 572 total population of the study area 315 were adults (≥ 18 years) (Source - Register of Urban Slum11). According to Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2010, 35 per cent of adult Indians are tobacco users12. Thus it was expected that of the 315 adults, 111 will be tobacco users. The intention was to take all current adult tobacco users in this study. The total current adult tobacco users (both smokers and smokeless) of the slum constituted our study population and this came out to be 132; thus complete enumeration method was employed. Four tobacco users were excluded from the study (one had stage IV bronchogenic carcinoma, one denied consent and two were absent despite three home-visits). Ultimately 128 current tobacco users were studied. Data were collected by interview using a pre-designed, pre-tested, semi-structured schedule, after obtaining necessary clearance from institutional Ethics Review Board (ERB). Nicotine dependence was assessed by Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND) questionnaire. This questionnaire has been extensively used in various countries, and its reliability has also been confirmed in different settings and populations9,10.

Operational definition: Current smokers were defined as who were smoking at the time of survey and had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime13. Cigarettes, beedi, smoking pipes, cigars were considered as smoked products. Current smokeless tobacco users were defined as persons either chewing tobacco or snuff at present and had chewed tobacco 20 or more times in their lifetime14. Smokeless tobacco products consist of chewing tobacco, moist snuff and dry snuff. Score less than 4, 4 to 6 and more than 6 in Fagerström test for nicotine dependence was interpreted as low, medium and high level of nicotine dependence, respectively9,10.

Statistical analysis: Categorical data were expressed in proportions, while continuous data were expressed in mean values. In contingency tables, significance of association between the two attributes was analyzed using chi-square (χ2) test. Difference between two mean values was tested by unpaired Student's t test. Degree and direction of relationship between two variables was computed by Pearson's product moment correlation co-efficient (r). Scores were assigned for categorical variables. A logistic regression model (forward stepwise conditional method) was also generated using intention to quit [yes(0) / no(1)], as the outcome / dependent variable. P< 0.05 was considered significant. All the statistical analysis was done in SPSS software, version 19.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results & Discussion

Mean age of the study population (n=128) was 41.1 ± 15.7 (range 18-77) years. Males were 89.8 per cent (n=115). Majority (n=57, 44.5%) used exclusively smokeless tobacco, 21.9 per cent (28) were smokers and 33.6 per cent (43) used both. Eighty one (63.3%) study subjects wanted to quit tobacco.

Majority of the tobacco users who did not want to quit belonged to the age group of more than 40 years (66.0%), were illiterate (55.3%), started using tobacco at 11 – 15 years of age (57.4%), had been using tobacco for 20 years or more (70.2%), were daily tobacco users (91.5%), and highly dependent on nicotine (80.9%). While majority of the users who wanted to quit were comparatively younger (≤ 30 years) (44.4%), more educated, started use after 15 years (82.7%), had been using tobacco for ≤ 20 years(65.4%), and had low and medium level of nicotine dependence(72.8%). All these association were significant. Mean FTND score was significantly higher among those who did not intent to quit (Table I). Majority of the people (n=49/60, 81.7%) who were highly dependent to nicotine never tried to quit tobacco, while most of the low nicotine dependents (n=22/31, 71.0%) tried to quit, though ultimately failed. 69.2 per cent of females want to quit while 62.6 per cent of males want to quit tobacco.

Table I.

Distribution of study population according to intention to quit tobacco and different variables (n=128)

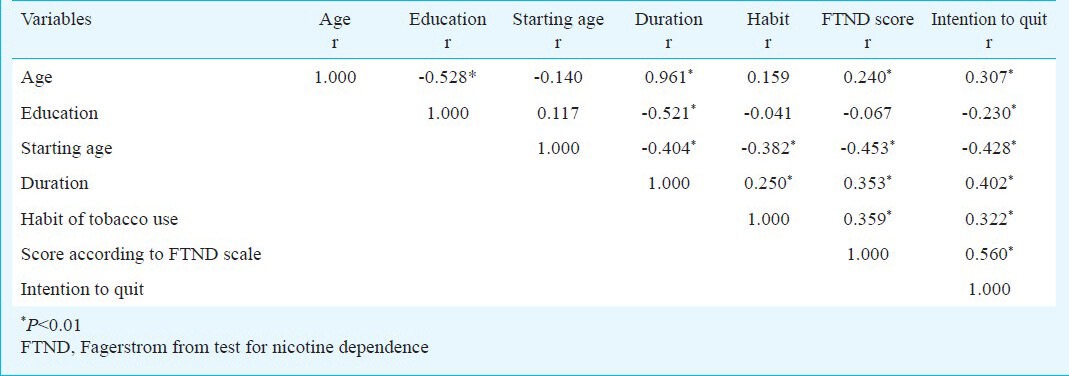

Intention to quit was more among more educated person (r = - 0.230) and occasional tobacco users (r = 0.322). In contrast, intention of quitting was difficult with an increase in age (r = 0.307), who initiated tobacco at an early age (r = − 0.428), using tobacco for a longer duration (r = 0.402), and an increase in nicotine dependence score (r=0.560) (Table II).

Table II.

Seven variables correlation matrix showing relationship between the dependent and the independent variables (n=128)

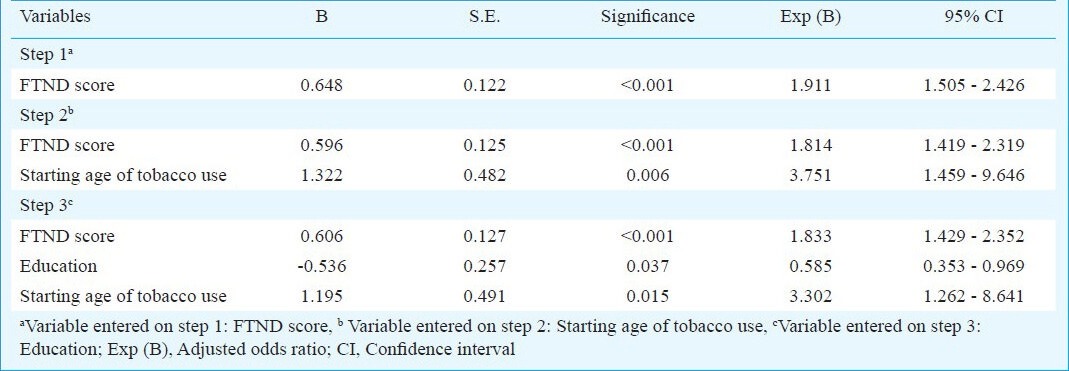

FTND score, starting age of tobacco use and education of the subjects combined explained 37.8 to 51.7 per cent variation of intention of quitting, while FTND score alone was responsible for 31.6 to 43.2 per cent variation. FTND score and starting age of tobacco use came out to be the significant predictors of quitting intention from the regression model. Tobacco users having high FTND score and those who started tobacco use early in life were 1.83 and 3.30 times more unintended to quit, respectively (Table III).

Table III.

Binary logistic regression model for predictors of intention of quitting among the adult tobacco users (n=128)

More than 60 per cent subjects (63.3%) were intended to quit tobacco; the value was higher than that reported in other studies from India15,16. Our study showed that quitting became difficult with an increase in age, and that less education was associated with difficulty in quitting as shown by Rosenthal et al4. But, in contrast, Rafful et al5 found that less education was associated with successful quitting, and initiation at younger age was associated with difficulty in quitting. Abdolahinia et al6 also reported that mean age of initiation of tobacco use was higher among the quitters. Similar findings observed in the present study were probably due to higher level of nicotine dependence associated with younger age of initiation. People with low FTND score were found to be more interested to quit as shown by Bernstein et al17.

A logistic regression model was constructed which explained 37.8 to 51.7 per cent variation of quitting behaviour was due to independent variables. This model was able to predict correctly 84.4 per cent of quitting behaviour; while John et al18 could predict 72.1 per cent. Abdolahinia et al6 found age at initiation of smoking as the most important predictors of quitting; in the present study also age, habit of use and FTND score were seen as important predictors of quitting. However, it was the FNTD score alone that was significant in the present study.

Suitable plan for quitting should be developed depending on the FTND score of an individual, the most important determinant of quitting. Multicentric studies need to be undertaken to find out other predictors of quitting behaviour.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research ICMR, New Delhi, for providing Short Term Studentship (STS) to the first author (KI).

References

- 1.Wallace RB, editor. 15th ed. New York, USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008. Maxcy-Rosenau-Last. Public health and preventive medicine; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace RB, editor. World Health Organization; 2013. [accessed on May 13, 2014]. Tobacco. Fact Sheet N 339. July. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008. The MPOWER Package. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal L, Carroll-Scott A, Earnshaw VA, Sackey N, O’Malley SS, Santilli A, et al. Targeting cessation: understanding barriers and motivations to quitting among urban adult daily tobacco smokers. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1639–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rafful C, García-Rodríguez O, Wang S, Secades-Villa R, Martínez-Ortega JM, Blanco C. Predictors of quit attempts and successful quit attempts in a nationally representative sample of smokers. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1920–3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdolahinia A, Sadr M, Hessami Z. Correlation between the age of smoking initiation and maintaining continuous abstinence for 5 years after quitting. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:755–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg A, Singh MM, Gupta VK, Garg S, Daga MK, Saha R. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco smoking, awareness of hazards, and quitting behavior among persons aged 30 years or above in a resettlement colony of Delhi, India. Lung India. 2012;29:336–40. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.102812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur J, Sinha SK, Srivastava RK. Integration of tobacco cessation in general medical practice: need of the hour. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109:925–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebbert JO, Patten CA, Schroeder DR. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence – smokeless tobacco (FTND-ST) Addict Behav. 2006;31:1716–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bengal, India: Department of Community Medicine, Burdwan Medical Collge; 2013. Department of Community Medicine, Burdwan Medical College, Burdwan Register of urban slum, Burdwan, W. [Google Scholar]

- 12.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2010. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), India 2009-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha I, Paul B, Dey TK. An epidemiological study of smoking among adult males in a rural area of Hooghly district, West Bengal, India. J Smok Cessat. 2008;3:47–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson DE, Mowery P, Tomar S, Marcus S, Giovino G, Zhao L. Trends in smokeless tobacco use among adults and adolescents in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:897–905. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surani NS, Gupta PC, Fong TG, Pednekar MS, Quah AC, Bansal-Travers M. Intention to quit among Indian tobacco users: findings from International Tobacco Control Policy evaluation India pilot survey. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:431–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raute LJ, Sansone G, Pednekar MS, Fong GT, Gupta PC, Quah AC, et al. Knowledge of health effects and intentions to quit among smokeless tobacco users in India: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) India Pilot Survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cabral L, Cydulka RK, Schwegman D, Larkin GL, et al. Nicotine dependence, motivation to quit, and diagnosis among adult emergency department patients who smoke: a national survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1277–82. doi: 10.1080/14622200802239272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John U, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf HJ, Schumann A. Nicotine dependence, quit attempts, and quitting among smokers in a regional population sample from a country with a high prevalence of tobacco smoking. Prev Med. 2004;38:350–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]