Abstract

Cholestatic liver injury appears to result from the induction of hepatocyte apoptosis by toxic bile salts such as glycochenodeoxycholate (GCDC). Previous studies from this laboratory indicate that cathepsin B is a downstream effector protease during the hepatocyte apoptotic process. Because caspases can initiate apoptosis, the present studies were undertaken to determine the role of caspases in cathepsin B activation. Immunoblotting of GCDC-treated McNtcp.24 hepatoma cells demonstrated cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and lamin B1 to fragments that indicate activation of effector caspases. Transfection with CrmA, an inhibitor of caspase 8, prevented GCDC-induced cathepsin B activation and apoptosis. Consistent with these results, an increase in caspase 8–like activity was observed in GCDC-treated cells. Examination of the mechanism of GCDC-induced caspase 8 activation revealed that dominant-negative FADD inhibited apoptosis and that hepatocytes isolated from Fas-deficient lymphoproliferative mice were resistant to GCDC-induced apoptosis. After GCDC treatment, immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated Fas oligomerization, and confocal microscopy demonstrated ΔFADD-GFP (Fas-associated death domain–green fluorescent protein, aggregation in the absence of detectable Fas ligand mRNA. Collectively, these data suggest that GCDC-induced hepatocyte apoptosis involves ligand-independent oligomerization of Fas, recruitment of FADD, activation of caspase 8, and subsequent activation of effector proteases, including downstream caspases and cathepsin B.

Introduction

Cholestasis is a feature of many chronic human liver diseases. Although bile ducts receive the initial insult in many of these disorders, progression of the liver disease ultimately results from damage of hepatocytes by toxic hydrophobic bile salts (1). Earlier studies have demonstrated that (a) failure of bile salt excretion in cholestasis leads to high concentrations of toxic bile salts within hepatocytes (2, 3) and (b) these toxic bile salts induce hepatocellular death by apoptosis (4, 5). However, the mechanism(s) by which bile salts induce hepatocyte apoptosis remain unclear.

Over the past few years, proteases have been shown to play multiple roles in apoptotic biochemical and morphological changes (6). One classification scheme distinguishes between initiator, amplifier, and machinery (effector) proteases (7). We have recently demonstrated that cathepsin B is activated and translocated to the nucleus during bile salt–induced apoptosis (8). Inhibition of cathepsin B with highly selective protease inhibitors, expression of the cystatin A transgene, or antisense approaches attenuates bile salt–induced apoptosis (9). However, cathepsin B would appear to be an effector protease, based on its nondiscriminatory endopeptidase activity and late activation in apoptosis (9). Thus, its activation is likely dependent on upstream initiator or amplifier proteases.

Caspase proteases have been widely implicated in many models of apoptosis (10). At least 13 (11 human and 2 murine) mammalian members of the caspase family have been cloned and characterized to date (11, 12). Caspases 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 13 have been implicated in apoptosis, whereas caspases 1, 4, and 5 likely participate in modulation of cytokines (13). Caspases 2, 8, 9, and 10, which have long prodomains, are thought to be involved in the signaling cascades initiating apoptosis (13, 14). In particular, caspase 8 has been found to be a prominent signaling caspase involved in initiation of apoptosis by the Fas, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) type I, and DR3 receptors (15, 16). Caspase 8 is also abundant in the liver (15, 16), making this caspase an attractive candidate to function as an initiator protease upstream of cathepsin B in bile salt–mediated hepatocyte apoptosis.

Caspase 8 can be activated by several potential mechanisms. Although the most widely studied mechanism involves procaspase 8 activation at the level of the plasma membrane after ligation of the death receptors Fas, TNFR 1, and DR3 (15–17), caspase 8 can also be activated at the level of the endoplasmic reticulum by a process involving a protein complex containing p28 Bap31, and Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL (18). In addition, Scaffidi et al (19) have also demonstrated enhanced activation of caspase 8 during apoptosis after mitochondrial dysfunction in specific cell types.

The overall objectives of the present study were to examine the role of caspases in bile salt–induced apoptosis and to explore the possibility of a mechanistic link between cathepsin B and caspases, particularly caspase 8. To address these objectives, hepatocytes were treated with glycochenodeoxycholate (GCDC), a bile salt that accumulates intrahepatically during cholestasis and induces hepatocyte apoptosis at pathophysiological concentrations (3, 5).

Methods

Culture of McNtcp.24 cells and mouse hepatocytes.

The rat McNtcp.24 cell line, which transports bile salts and undergoes bile salt–mediated apoptosis in a manner similar to primary rat hepatocytes, was cultured as described previously (9). Mouse hepatocytes were isolated from lymphoproliferative (lpr) and wild-type (MRLMPJ+/+) male mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA), purified by Percoll gradient centrifugation, and cultured as described for rat hepatocytes (20). Viability of isolated hepatocytes was always >95%.

Quantification of cathepsin B activity and apoptosis.

Single-cell intracellular cathepsin B–like activity was measured using the fluorogenic protease substrate Z-Val-Leu-Lys-CMAC (VLK-CMAC) and digitized fluorescence microscopy as described previously (9). Apoptosis was quantitated by assessing nuclear changes using the nuclear binding dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dihydrochloride and fluorescence microscopy (21).

In vitro enzyme assays.

Protease inhibitor studies were performed as described by Thornberry and coworkers (22). Briefly, cathepsin B assays were initiated by adding purified enzyme to cuvettes containing 20 mM MOPS buffer, pH 6.0, 20 μM Z-Arg-Arg-AMC, and the desired concentration of the protease inhibitor. Fluorescence was continuously monitored using a Perkin-Elmer model LS 50 fluorometer (Norwalk, Connecticut, USA). For those inhibitors in which the inhibition was rapid, leading to linear rates of reaction product generation, the Ki was determined as described by Zhou et al and coworkers (23). For those inhibitors with curvilinear rates of reaction product generation, the second-order rate constant was determined as described by Morrison (24).

After cytosolic extracts were prepared as described (25), caspase 8–like activity was assayed by adding 50 μl of cytosol to 450 μl of buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM DTT, 0.1% 3-([3-cholamidopropyl]-dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 0.5 mM PMSF, 100 U/ml aprotinin (Trasylol), and 20 μM IETD-AFC. Fluorescence was monitored as described above.

Kinetic analysis of IETD-AMC and DEVD-AFC hydrolysis by recombinant caspases 3, 6, 7, and 8 was performed in 20 mM PIPES buffer (pH 7.2) containing 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose (26), and concentrations of substrate ranging from 1 to 100 μM. After addition of recombinant protease (100 ng/ml), fluorescence was continuously monitored. Km and Vmax maximum velocity were calculated using the program Enzfitter (Erithacus Software, London, United Kingdom).

Transient transfection of McNtcp.24 cells.

The coding sequence for CrmA was cloned into the pCl neomammalian expression vector (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). An expression vector for the MCV 159 protein, pCl-MC159, was obtained from J. I. Cohen (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) (27). pEGFP-Cl (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, California, USA) contains the coding sequence of green fluorescent protein (GFP). The expression vector pcDNA3-GFP-ΔFADD, obtained from H. Wajant (Stuttgart, Germany), encodes a polypeptide that contains GFP fused to the COOH-terminal death domain of Fas-associated death domain (FADD) (28). This construct binds to Fas but acts as a dominant-negative (DN) inhibitor because it lacks the NH2-terminal death effector domain of FADD.

McNtcp.24 cells (1.5 × 105 cells/ml) were transfected using lipofectamine (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) as described previously by us in detail (8). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the viability of transfected cells by trypan blue exclusion was always >95%. The transfection efficiency was determined by transfecting the cells with pEGFP-Cl and assessing the percentage of GFP-expressing cells by flow cytometry (FACStar Plus; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, California, USA).

Confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy of pcDNA3-GFP-ΔFADD–transfected cells was performed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Axiovert 100M-LSM 310, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, New York, USA). GFP fluorescence was imaged using excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm and 505 nm, respectively.

Immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis for lamin B1 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) was performed using whole-cell lysates as described by Martins et al. (29), except that polyvinylidine fluoride membrane was substituted for nitrocellulose. Immunoblot analysis for CrmA was performed on McNtcp.24 cells lysed in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail; Boehringer- Mannheim Biochemica, Mannheim, Germany). After electrophoresis in gels containing 10% polyacrylamide, polypeptides were transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was blocked with 1% wt/vol skim milk in 20 mM Tris, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.0, for 30 min, and then incubated for 45 min with a 1:500 dilution of mouse anti-CrmA (PharMingen, San Diego, California, USA). After washing, membranes were incubated for 30 min with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, Santa Cruz, California, USA) and washed again. Bound antibody was visualized using chemiluminescent substrate (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA) and exposed to Kodak XAR5 film.

Fas cross-linking and immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation of cross-linked Fas receptor was performed as described in the literature (30, 31). Briefly, cells were treated with 2 mM 3,3′-dithio-bis(sulfosuccinimidyl proprionate) (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Illinois, USA), a cleavable cross-linker, in PBS for 10 min at 4°C. After the reaction was quenched with 10 mM NH4 acetate for 5 min at 4°C, cells were washed with PBS, scraped into 1 ml PBS containing 50 μM leupeptin, 25 μM pepstatin A, 2 mM PMSF, and 1 mM benzamidine, and lysed by sonication. After removal of cellular debris by centrifugation, immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating 0.5 mg of supernatant protein in 1 ml of PBS containing the desired concentration of hamster anti–mouse Fas antibody (PharMingen) and 100 μl protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biochemicals) at 4°C overnight with agitation. Polypeptides eluted by boiling for 5 min in 5× Laemmli sample buffer were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blotted with rabbit polyclonal anti–mouse Fas (Santa Cruz Biochemicals) followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG (BioSource International, Camarillo, California, USA).

Reverse transcriptase PCR for Fas and Fas ligand.

Primers for Fas were: sense, 5′ TGA TGA GCA CAC CTT TGA TGA C; antisense, 5′ ATT CTT CCC AGG ACA AAC CAA C. Primers for Fas ligand (FasL) were: sense, 5′ACC TTT AAA CTC ACC TTC C; antisense, 5′ AAC ACC CCT CTT ATT TCT C. Total cellular RNA was isolated using the Trizol reagent (GIBCO BRL). After reverse transcription (32), the cDNA product was amplified by PCR. Samples were heated to 94°C for 2 min and then amplified for 35 cycles with the following cycle times: 94°C for 1 min, 59.7°C (Fas) or 52.6°C (FasL) for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. PCR for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was performed as described previously (32). The amplified products (15 μl) were separated on 1% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed using ultraviolet (UV) illumination. PCR products were sequenced using dye terminator technology.

Statistical analysis.

All data represent at least three independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Differences between groups were compared using ANOVA for repeated measures and a post hoc Bonferroni test to correct for multiple comparisons.

Materials and reagents.

DEVD-AMC and the tetrapeptide caspase inhibitors Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-aspartic acid aldehyde (DEVD-CHO), Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-aspartic acid fluoromethylketone (DEVD-fmk), Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-aspartic acid aldehyde (YVAD-CHO), and Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-aspartic acid fluoromethylketone (YVAD-fmk) were from Bachem Biosciences (King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, USA). GCDC (>96% pure by thin-layer chromatography), cathepsin B, and DAPI were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). IETD-AFC and FA-fmk were obtained from Enzyme Systems Products (Dublin, California, USA). CA-074-Me was obtained from Peptides International (Louisville, Kentucky, USA). VLK-CMAC was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon, USA). Recombinant caspases 3, 6, 7, and 8 were obtained from PharMingen.

Results

Is cathepsin B activated during treatment of McNtcp.24 cells with GCDC, and does inhibition of cathepsin B reduce apoptosis?

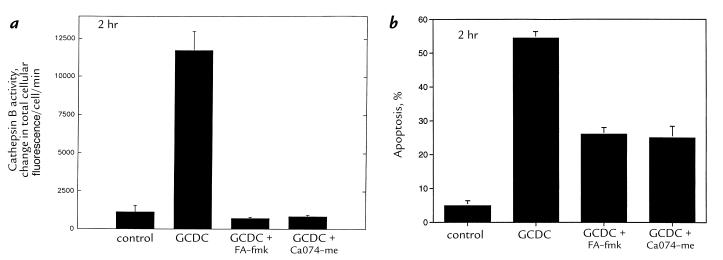

When cathepsin B activity was monitored in cultured cells using digitized video microscopy, a fivefold increase in intracellular VLK-CMAC hydrolysis was observed after treatment with 50 μM GCDC for two hours (Fig. 1). The cathepsin B inhibitors FA-fmk and CA-074-Me reduced the GCDC-mediated increase in cathepsin B activity and apoptosis in McNtcp.24 cells (Fig. 1). These data using the McNtcp.24 cells confirm and extend our previous observations that cathepsin B activity increases and contributes to bile salt–mediated apoptosis in primary rat hepatocytes (8).

Figure 1.

Cathepsin B activity increases during GCDC-induced apoptosis of McNtcp.24 cells, and cathepsin B inhibitors reduce apoptosis. Cells were incubated in medium alone or with 50 μM GCDC in the absence or presence of 100 μM FA-fmk (throughout the experiment) or 0.1 μM CA-074-Me (pretreatment for 10 min before adding GCDC). Cathepsin B activity (a) was measured in cells after 2 h of incubation using the fluorogenic substrate VLK-CMAC as described in Methods. P < 0.01 for GCDC vs. control, GCDC plus FA-fmk, or GCDC plus CA-074-Me by ANOVA. Apoptosis (b) was quantitated after 2 h of incubation as described in Methods. P < 0.01 for GCDC vs. control, GCDC plus FA-fmk, or GCDC plus CA-074-Me by ANOVA. GCDC, glycochenodeoxycholate.

Are caspases activated in bile salt–mediated apoptosis, and does caspase inhibition reduce apoptosis?

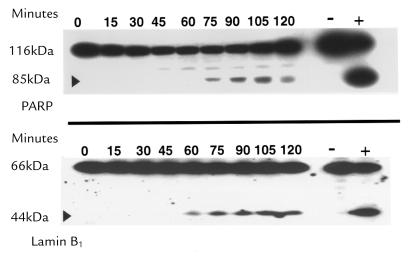

Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that PARP and lamin B1, two substrates cleaved by caspases in many models of apoptosis, were also cleaved in GCDC-treated McNtep.24 cells (Fig. 2). These results suggested that, in addition to cathepsin B, caspases are activated in GCDC-induced hepatocyte apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Immunoblot analysis shows PARP and lamin B1 cleavage. McNtpc.24 cells were treated with GCDC for the indicated length of time. HL-60 cells with and without etoposide appear on the right as positive and negative controls, respectively. The appearance of 89-kDa and 45-kDa cleavage products of PARP (top) and lamin B1 (bottom), respectively, are characteristic of caspase-mediated cleavage. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

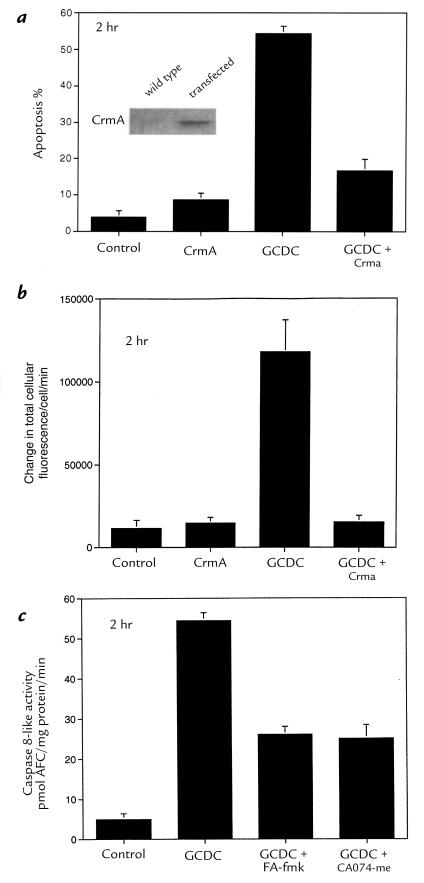

To assess the contribution of caspase activation to bile salt–induced apoptosis, we initially sought to determine the effect of caspase inhibitors on GCDC-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis. Unexpectedly, we found that the commercially available tetrapeptide caspase inhibitors DEVD-CHO, DEVD-fmk, YVAD-CHO, and YVAD-fmk all inhibited cathepsin B (Table 1). The fluoromethylketone inhibitors (fmk) inhibited cathepsin B with curvilinear rates, indicating a slow initial reaction between the enzyme and the inhibitor followed by a fast transformation step. In contrast, the peptide aldehydes (CHO) inhibited cathepsin B with linear rates, indicating a rapid reaction between the inhibitor and the enzyme. Although DEVD-fmk and DEVD-CHO have similar potency for cathepsin B inhibition (micromolar concentrations), YVAD-fmk (nanomolar concentration) was more potent than YVAD-CHO (micromolar concentration) in inhibiting cathepsin B. Because these compounds inhibited cathepsin B, we were unable to use them to determine whether caspases contributed to bile salt–mediated apoptosis.

Table 1.

Inhibition of cathepsin B by synthetic tetrapeptide-based caspase inhibitors

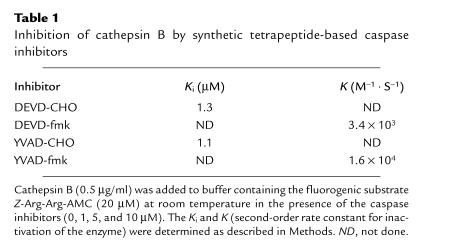

As an alternative approach, the CrmA protein was used to inhibit caspases. After verifying that CrmA did not inhibit cathepsin B activity in vitro (data not shown), we demonstrated that CrmA could be expressed in McNtcp.24 cells (Fig. 3). To ascertain the feasibility of performing cell population studies, the transfection efficiency of McNtcp.24 cells was determined using a GFP construct. As assessed by flow cytometry, >80% of McNtcp.24 cells could be transiently transfected using lipofectamine (data not shown). Because of this high transfection efficiency, we were able to determine the effect of CrmA on apoptosis without isolating the transfected cells. We observed that GCDC-mediated apoptosis was inhibited in McNtcp.24 cells transfected with CrmA (Fig. 3). These data support the interpretation that, in addition to cathepsin B, caspases also contribute to GCDC-induced apoptosis of McNtcp.24 cells.

Figure 3.

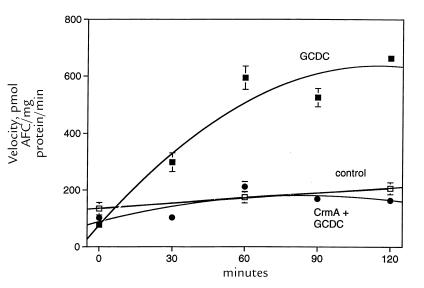

CrmA expression prevents cathepsin B activation and apoptosis in McNtcp.24 cells treated with GCDC. In contrast, inhibition of cathepsin B activity does not prevent the increase in caspase 8 activity. Forty-eight hours after transfection with an expression vector for CrmA or the empty vector, McNtcp.24 cells were treated with 50 μM GCDC or the diluent. After 2 h of incubation, apoptosis (a) was quantitated as described in Fig. 1. P < 0.01 for GCDC vs. control, CrmA, or GCDC plus CrmA. The inset shows an immunoblot demonstrating CrmA expression in transfected cells. Cathepsin B activity (b) was measured after 2 h of incubation using the fluorogenic substrate VLK-CMAC. P < 0.01 for GCDC vs. control, CrmA, or GCDC plus CrmA by ANOVA. Caspase 8 activity (c) was assessed in lysates prepared from McNtcp.24 cells incubated in medium alone or with 50 μM GCDC at 37°C in the presence of 100 μM FA-fmk or 0.1 μM CA-074-Me as described in Fig. 1. P = NS for GCDC vs. GCDC plus FA-fmk or GCDC plus CA-074-Me. P < 0.01 for all GCDC-treated cells compared with control. NS, not significant.

Are caspase and cathepsin B activity mechanistically linked in GCDC-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis?

If caspases and cathepsin B were activated in independent parallel pathways, then inhibition of either protease would not reduce apoptosis. The observation that CrmA and the cathepsin B inhibitors both reduced apoptosis suggested that caspases and cathepsin B are linked in a linear apoptotic pathway. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effect of CrmA on cathepsin B activity (Fig. 3). CrmA prevented cathepsin B activation. In contrast, cathepsin B inhibitors did not abrogate cleavage of PARP and lamin B1 in GCDC-treated cells (data not shown). Furthermore, cathepsin B inhibitors did not prevent cleavage of the fluorogenic caspase substrate IETD-AFC (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that caspases and cathepsin B are linked mechanistically in bile salt–mediated apoptosis, with cathepsin B activation occurring “downstream” of the caspase(s) cleaving IETD-AFC.

Is caspase 8 activated during treatment of McNtcp.24 cells with GCDC?

The observation that CrmA, which has a high affinity for caspase 8 (23), inhibits GCDC-mediated apoptosis of McNtcp.24 cells raises the possibility that caspase 8 is activated during treatment with GCDC. The observation that cytosol from GCDC-treated cells cleaves IETD-AFC (Fig. 3) provides additional support for this view.

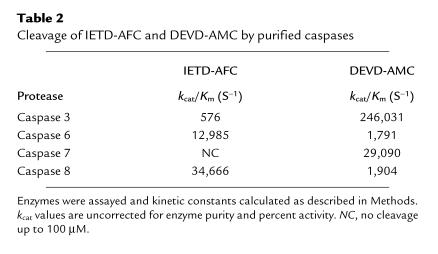

To see whether IETD-AFC is selective for caspase 8, we monitored the cleavage of substrates IETD-AFC and DEVD-AMC by four recombinant caspases: 3, 6, 7, and 8. DEVD-AMC cleavage was assessed to assure that the enzymes were active and because the catalytic rate (kcat)/Km values for caspases 3, 6, and 7 with this substrate are known (33). Indeed, our kcat/Km values for DEVD-AMC cleavage by caspases 3, 6, and 7 were comparable to published values (33). Caspase 8 hydrolyzed IETD-AFC more efficiently than the other caspases, confirming that this substrate is a somewhat selective caspase 8 substrate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cleavage of IETD-AFC and DEVD-AMC by purified caspases

We next determined the time course for activation of IETD-AFC hydrolytic activity in cytosolic extracts from GCDC-treated McNtcp.24 cells (Fig. 4). IETD-AFC cleavage activity increased fourfold within two hours of treatment with GCDC (P < 0.01). The magnitude of IETD-AFC cleavage observed after treatment of McNtcp.24 cells with GCDC was virtually identical to that observed after treatment with TNF-α (28 ng/ml) plus actinomycin D (325 nM) (data not shown), a combination that is known to induce apoptosis by a caspase 8–dependent pathway (34). Thus, the magnitude of IETD-AFC hydrolytic activity observed in GCDC-mediated apoptosis was comparable to an established caspase 8–dependent model of apoptosis. No increase in IETD-AFC hydrolytic activity was observed in untreated or CrmA-transfected cells (Fig. 4). Furthermore, after treatment with GCDC, the 55- and 53-kDa isoforms of procaspase 8 detected by immunoblot analysis decreased by ∼40% after two hours, consistent with processing of part of the available procaspase 8 to active subunits (data not shown). These data demonstrate an increase in CrmA-suppressible caspase 8–like protease activity during GCDC-induced hepatocyte apoptosis.

Figure 4.

The increased cleavage of IETD-AFC in cytosol from GCDC-treated McNtcp.24 cells is diminished by prior transfection with CrmA. Untransfected McNtcp.24 cells were incubated in the absence (control; open squares) or presence of 50 μM GCDC (solid squares and solid circles). Cells were transfected with CrmA for 48 h before incubation in the presence of GCDC (solid circles). Cytosol was prepared at selected time points and assayed for caspase 8–like protease activity using the fluorogenic substrate IETD-AFC.

How is caspase 8 activated during GCDC-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis?

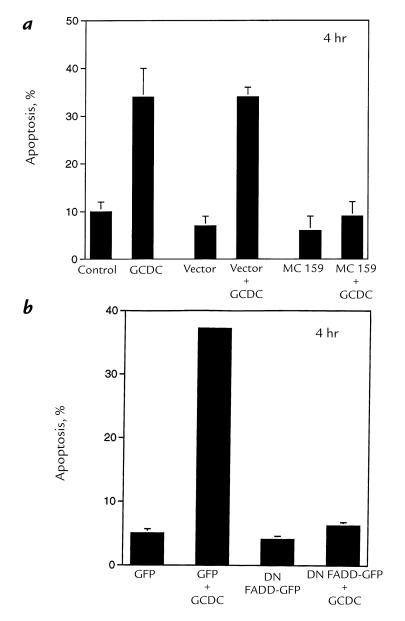

Because caspase 8 can be activated by binding to FADD in the death-induced signaling complex (DISC) in many models of apoptosis, we next tested the hypothesis that bile salt–mediated apoptosis is dependent on a DISC interaction. We used the molluscum contagiosum virus protein MC159, which competes with procaspase 8 for binding to FADD and thereby disrupts the DISC (27), to examine this possibility. Transient expression of MC159 reduced the number of apoptotic GCDC-treated McNtcp.24 cells from 46% ± 4.5% to 8% ± 1.5% (P < 0.01, Fig. 5). These data suggest that bile salt–induced apoptosis involves a FADD/caspase 8–dependent interaction. In further support of this hypothesis, we observed that transient transfection with a dominant negative FADD (DN-FADD) construct also inhibited GCDC-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

MC159 or DN FADD–GFP inhibits apoptosis in GCDC-treated McNtcp.24 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection with plasmid encoding MC159 (a) or DN FADD–GFP (b), McNtcp.24 cells were treated with 50 μM GCDC or diluent. At the indicated time points, cells were stained with DAPI and examined by microscopy. In the top panel, P < 0.01 for GCDC vs. control, vector (empty plasmid), MC159, or MC159 plus GCDC by ANOVA; P = NS between GCDC vs. vector plus GCDC. In the bottom panel, P < 0.01 for GFP plus GCDC vs. GFP, DN FADD–GFP, or DN FADD–GFP plus GCDC by ANOVA. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DN, dominant negative; FADD, Fas-associated death domain; GFP, green flourescent protein.

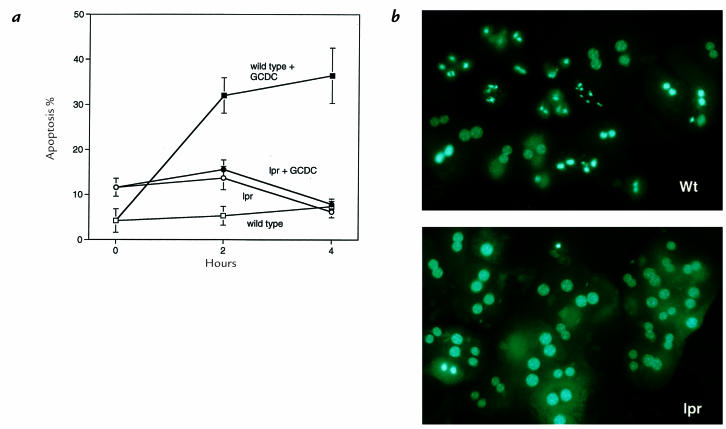

Because Fas receptor activation is a common mechanism for FADD/caspase 8–dependent apoptosis in the liver, we determined whether GCDC could induce apoptosis in hepatocytes isolated from the lpr mouse. The lpr mouse has minimal Fas expression, and its hepatocytes are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis (35, 36). Mouse hepatocytes isolated from the lpr mouse were highly resistant to GCDC-mediated apoptosis compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6). These data strongly suggested that GCDC-induced apoptosis occurs via a Fas-dependent mechanism.

Figure 6.

Hepatocytes isolated from the Fas-deficient lpr mouse are resistant to GCDC-induced apoptosis. Hepatocytes isolated from lpr and wild-type (Wt; MRLMPJ+/+) mice were cultured in medium for 8 h before addition of diluent or 50 μM GCDC for another 4 h. At 0, 2, and 4 h of incubation, apoptosis was quantitated morphologically (a) as described in Fig. 1. Representative photomicrographs of MRL and lpr mouse hepatocytes treated with 50 μM GCDC for 2 h before DAPI staining (b). Note the chromatin margination/condensation and nuclear fragmentation in MRL hepatocytes and their relative absence in the lpr hepatocytes.

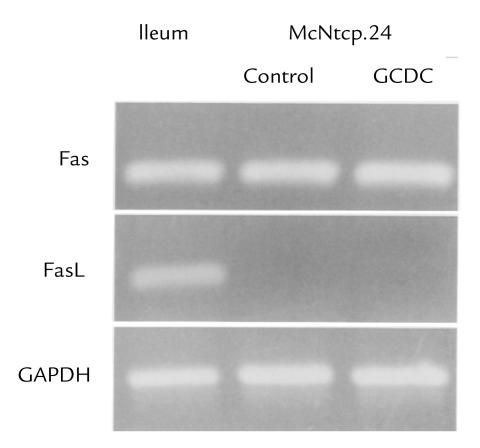

To further examine the role of the Fas pathway in bile salt–induced apoptosis, we examined the expression of Fas and FasL in the McNtcp.24 cells used for the caspase 8 measurements. Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR demonstrated expression of Fas mRNA in McNtcp.24 cells (Fig. 7). Furthermore, these cells underwent apoptosis in the presence of exogenously added FasL (data not shown), demonstrating that the Fas signaling pathway is intact in these cells. Although McNtcp.24 cells express Fas, they do not express FasL mRNA, even after exposure to GCDC (Fig. 7), raising the possibility that bile salt–induced Fas activation might occur in a FasL-independent manner.

Figure 7.

McNtcp.24 cells express Fas receptor but not FasL mRNA. After McNtcp.24 cells were cultured for 2 h in the presence or absence of 50 μM GCDC, total RNA was isolated for subsequent RT-PCR using Fas, FasL, and GAPDH. RNA from ileum served as a positive control for both Fas receptor and FasL. The identities of the PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing. FasL, Fas ligand; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; RT, reverse transcriptase.

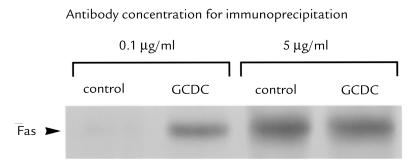

Do toxic bile salts cause Fas oligomerization and the corresponding intracellular aggregation of FADD?

Recent studies have demonstrated that UV light can induce oligomerization in a FasL-independent manner (30, 31). This oligomerization can be demonstrated by performing immunoprecipitation with limiting amounts of anti-Fas antibodies (30, 31). Under such conditions, oligomerized Fas is precipitated more efficiently than Fas monomer (30, 31), possibly because Fas is oligomerized into macromolecular aggregates larger than trimers (37). When this approach was applied to primary mouse hepatocytes McNtcp.24, limiting amounts of antibody precipitated more Fas after GCDC treatment than before (Fig. 8). Performance of the immunoprecipitation using excess amounts of antibody confirmed that equal amounts of Fas protein were present before and after GCDC treatment (Fig. 8). Coupled with the observation that FasL mRNA is undetectable in these cells, these results are consistent with the view that GCDC induces a ligand-independent oligomerization of Fas.

Figure 8.

GCDC treatment of primary mouse hepatocytes cells results in Fas receptor oligomerization. Untreated and GCDC (50 μM)-treated cells were incubated with the cleavable cross-linking reagent 3,3′-dithio-bis(sulfosuccinimidyl proprionate) and lysed for immunoprecipitation using limiting (0.5 μg/ml) or excess (5 μg/ml) amounts of anti-Fas antibody. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitate was performed as described in Methods.

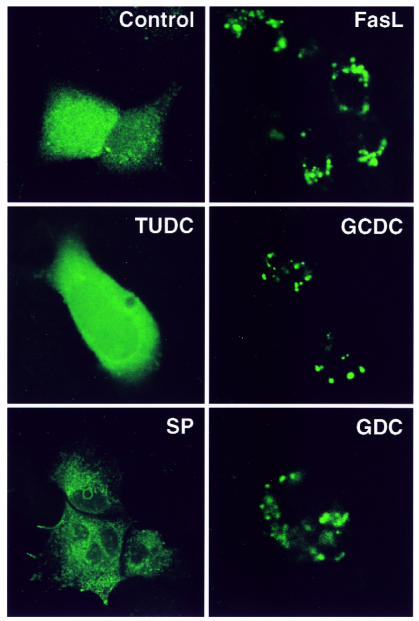

To confirm independently the apparent GCDC-induced Fas oligomerization, cells were transfected with DN FADD–GFP and examined after various treatments (Fig. 9). This construct encodes GFP fused to DN FADD, a truncated signaling molecule that binds to Fas but is unable to propagate death signals. In control cells, DN FADD–GFP had a diffuse cytosolic localization as by confocal microscopy reported previously (28). Treatment with FasL induced readily detectable DN FADD aggregation. Likewise, GCDC or glycodeoxycholate, another toxic bile salt, induced DN FADD aggregation. In contrast, ursodeoxycholate, a nontoxic hydrophilic bile salt, and staurosporine, a compound that induces apoptosis independent of Fas or caspase 8, did not cause DN FADD aggregation (38). These results indicate that multiple toxic bile salts induce Fas/FADD signaling, whereas nontoxic hydrophilic bile salts do not.

Figure 9.

Intracellular localization of DN FADD–GFP in McNtcp.24 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection with DN FADD–GFP, cells were either untreated (control) or treated with 10 ng/ml FasL, 50 μM tauro ursodeoxycholate (TUDC), 50 μM GCDC, 1 μM staurosporine (SP), or 50 μM glycodeoxycholate (GDC) for 4 h. GFP fluorescence was imaged by laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that (a) inhibition of either cathepsin B or caspases attenuates GCDC-induced apoptosis; (b) inhibition of caspases prevents the increase in cathepsin B activity, but cathepsin B inhibition does not prevent caspase activation; (c) increased caspase 8 hydrolytic activity accompanies treatment of McNtcp.24 cells with GCDC; (d) hepatocytes from Fas-deficient lpr mice are resistant to GCDC-induced apoptosis; and (e) GCDC induces Fas oligomerization, FADD aggregation, and apoptosis in the apparent absence of FasL. These novel observations not only place cathepsin B downstream of caspase 8 in bile salt–induced apoptosis but also suggest that caspase 8 activation occurs by a Fas-dependent, FasL-independent pathway. Each of these observations is discussed in greater detail below.

Cleavage of PARP and lamin B1 to signature fragments suggested activation of caspases 3 and 6 after GCDC treatment. These caspases are currently thought to be activated by upstream signaling caspases (13). Therefore, we sought to identify the upstream protease responsible for initiating the GCDC-induced apoptotic cascade. Our results suggest that caspase 8 might play this role. This conclusion is based on the observed increase in IETD-AFC cleavage activity and on inhibition of GCDC-induced apoptosis by CrmA, a cowpox viral serpin that potently inhibits caspases 1, 4, and 8, but not caspases 3, 6, 7, and 10 (23, 39). In previous experiments, we were unable to find an increase in caspase 1 activity during GCDC-mediated apoptosis using the fluorogenic substrate YVAD-AMC (5), thus eliminating caspases 1 and 4 as the CrmA-inhibitable protease causing apoptosis in our system. Caspase 10, another signaling caspase with NH2-terminal death effector domains, is not inhibited by CrmA (39). Thus, caspase 8 is likely to be the key target of CrmA during bile salt–induced apoptosis.

In addition to caspase 8, cathepsin B also appeared to be activated during GCDC-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. When we attempted to perform experiments to determine whether cathepsin B was downstream of caspase 8, we observed unexpected inhibition of cathepsin B with tetrapeptide fluoromethylketones and aldehydes designed to selectively inhibit caspases. Although the Ki for these inhibitors is over 1,000-fold lower for caspase 3 than for cathepsin B (the Ki for DEVD-CHO is 0.35 nM vs. 1.3 μM for cathepsin B), these inhibitors are frequently used in the 50–100 μM range in experiments using intact cells. Until the intracellular concentrations of the inhibitors are known, our results suggest that data relying solely on the use of high concentrations of these inhibitors need to be interpreted with caution, because the inhibitors might not be as selective as presumed.

As a result of these observations, we used CrmA to examine the relationship between caspases and cathepsin B. Inhibition of caspases with CrmA blocked the increase of cathepsin B activity, whereas inhibition of cathepsin B with FA-fmk or CA-074-Me did not block caspase activation. These data suggest that cathepsin B is downstream of and perhaps dependent on caspase 8 for activation. Consistent with this model, additional experiments using hepatocytes from a cathepsin B knockout mouse have confirmed that caspase 8 activation does not require cathepsin B, but cathepsin B does contribute to bile salt–induced apoptosis (Gores, G.J., unpublished observations).

The mechanism by which caspase 8 results in enhanced cathepsin B activity is currently unknown. Because cathepsin B is predominantly within acidic vesicles, a direct pathway might involve internalization of the Fas receptor/FADD/caspase 8 complex and fusion with cathepsin B–containing vesicles. Monney and coworkers (40) have previously suggested this pathway for death-receptor signaling to explain their observation that alkalinization of acidic vesicles reduces apoptosis. The internalization of the Fas receptor signaling complex may be facilitated by activation of the Fas receptor in a ligand-independent manner as observed in our studies. Internalization of the DISC and fusion with acidic vesicles may also explain how ceramide generation by acidic sphingomyelinase (also present in vesicles) occurs in apoptosis (40). Alternatively, caspase 8 could modulate vesicular function via an indirect, currently unidentified, cytosolic signaling pathway. Although further data are needed to elucidate the potential interactions between caspase 8 and acidic vesicles, the published data, along with the present observations on cathepsin B, suggest that acidic vesicles and their constituents may contribute to the execution of the apoptosis program.

Three additional observations suggest that bile salt–induced caspase 8 activation involves the Fas receptor and the adapter protein FADD. First, hepatocytes from Fas-deficient lpr mice are resistant to GCDC-induced apoptosis. Second, overexpression of the viral death-effector domain–containing protein MC159, which competitively inhibits the binding of caspase 8 to FADD, attenuates bile salt–induced apoptosis. Third, overexpression of DN-FADD inhibits GCDC-mediated apoptosis.

Despite the data implicating Fas and FADD in GCDC-induced apoptosis, FasL expression could not be detected by PCR even in GCDC-treated cells. Induction of Fas receptor–mediated cell death in the absence of FasL has been observed previously in Fas receptor overexpression systems (41) and UV-treated cells (30, 31). Using a cross-linking approach described in the latter study, we have demonstrated GCDC-induced Fas oligomerization despite the apparent absence of FasL. Studies with GFP–DN FADD likewise demonstrate Fas aggregation in cells treated with toxic bile salts. The potential mechanisms by which toxic bile salts directly induce these interactions are unknown but likely relate to the hydrophobicity of the bile salts and their ability to intercalate in membranes or bind to proteins (42). A better understanding of the precise mechanisms by which bile activates the Fas/FADD system may provide insight into Fas receptor dynamics as well as potential therapeutic strategies for cholestatic liver disease. These data do not, of course, rule out the possibility that bile salts might also promote oligomerization of other death-domain–containing receptors, such as the TRAIL receptor, which could also contribute to bile salt–mediated apoptosis in vivo.

In summary, data in the current study suggest that toxic bile salts cause cell death, in part by activating a protease cascade. The proximal signaling protease caspase 8 appears to be activated by toxic bile salts in a Fas receptor–dependent but FasL-independent manner. After caspase 8 activation, cathepsin B activity also increases. Inhibition of either protease attenuates apoptosis in vitro, suggesting that they both play a critical role in bile salt–induced apoptosis. The implications of these results for potential therapy of cholestatic liver disease are currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

The secretarial assistance of Sara Erickson and Deb Strauss is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Harald Wajant for generously providing pcDNA3-GFP-ΔFADD, and Jeffery Cohen and John Bertin (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) for furnishing pCl-MC159. We also are indebted to Anu Srinivasan (IDUN Pharmaceuticals, La Jolla, California, USA) for providing the anti–caspase 8 antisera. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK-41876 to G.J. Gores and CA-69008 to S.H. Kaufmann), the Gainey Foundation (to G.J. Gores), and the Mayo Foundation.

References

- 1.Schmucker DL, Ohta M, Kanai S, Sato Y, Kitani K. Hepatic injury induced by bile salts: correlation between biochemical and morphological events. Hepatology. 1990;12:1216–1221. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greim H, et al. Mechanism of cholestasis. 5. Bile acids in normal rat livers and in those after bile duct ligation. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greim H, et al. Mechanism of cholestasis. 6. Bile acids in human livers with or without biliary obstruction. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:846–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel T, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Increases of intracellular magnesium promote glycochenodeoxycholate-induced apoptosis in rat hepatocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2183–2192. doi: 10.1172/JCI117579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwo P, Patel T, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Nuclear serine protease activity contributes to bile acid-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes. Am J Physiol (Lond) 1995;268:G613–G621. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.4.G613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel T, Gores GJ, Kaufmann SH. The role of proteases during apoptosis. FASEB J. 1996;10:587–597. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.5.8621058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser A, Evan G. A license to kill. Cell. 1996;85:781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts LR, et al. Cathepsin B contributes to bile salt–induced apoptosis of rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 1997;12:1–10. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones BA, Roberts PJ, Faubion WA, Kominami E, Gores GJ. Cystatin A expression reduces bile salt–induced apoptosis in a rat hepatoma cell line. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G723–G730. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faleiro L, Kobayashi R, Fearnhead H, Lazebnik Y. Multiple species of CPP32 and Mch2 are the major active caspases present in apoptotic cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:2271–2281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alnemri ES, et al. Human ICE/CED-3 protease nomenclature. Cell. 1996;87:171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humke EW, Ni J, Dixit VM. ERICE, a novel FLICE-activatable caspase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15702–15707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvesen G, Dixit VM. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad M, et al. CRADD, a novel human apoptotic adaptor molecule for caspase-2, and FasL/tumor necrosis factor receptor-interacting protein RIP. Cancer Res. 1997;57:615–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85:803–815. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muzio M, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95(APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Signal transduction by DR3, a death domain-containing receptor related to TNFR-1 and CD95. Science. 1996;274:990–992. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng F, et al. p28 Bap31, a Bcl-2/Bcl-XL- and procaspase-8-associated protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:327–338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scaffidi C, et al. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klaunig J, et al. Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro. 1981;17:913–925. doi: 10.1007/BF02618288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Que FG, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF. Development and initial application of an in vitro model of apoptosis in rodent cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G106–G115. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.1.G106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornberry NA, et al. Inactivation of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme by peptide (acyloxy)methyl ketones. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3934–3940. doi: 10.1021/bi00179a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Q, et al. Target protease specificity of the viral serpin CrmA: analysis of five caspases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7797–7800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison JF. The slow-binding and slow, tight-binding inhibition of enzyme-catalysed reactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1982;7:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adjei P, Kaufmann SH, Leung W, Mao F, Gores GJ. Selective induction of apoptosis in Hep 3B cells by topoisomerase I inhibitors: evidence for a protease-dependent pathway that does not activate cysteine protease P32. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2588–2595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvesen G, Stennicke H. Biochemical characteristics of caspases-3, -6, -7, and -8. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25719–25723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertin J, et al. Death effector domain-containing herpesvirus and poxvirus proteins inhibit both Fas- and TNFR1-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1172–1176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wajant H, et al. Dominant-negative FADD inhibits TNFR60-, Fas/Apo1- and TRAIL-R/Apo2-mediated cell death but not gene induction. Curr Biol. 1998;8:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins LM, et al. Activation of multiple interleukin-1beta converting enzyme homologues in cytosol and nuclei of HL-60 cells during etoposide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7421–7430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aragane Y, et al. Ultraviolet light induces apoptosis via direct activation of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) independently of its ligand CD95L. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:171–182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehemtulla A, Hamilton C, Chinnaiyan AM, Dixit VM. Ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis is mediated by activation of CD-95 (Fas/APO-1) J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25783–25786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurosawa H, Que FG, Roberts LR, Fesmier PJ, Gores GJ. Hepatocytes in the bile duct-ligated rat express Bcl-2. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1587–G1593. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.6.G1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talanian RV, et al. Substrate specificities of caspase family proteases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasan A, et al. Bcl-xL functions downstream of caspase-8 to inhibit Fas- and tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-induced apoptosis of MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4523–4529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagata S. Mutations in the Fas antigen gene in lpr mice. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:3–8. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogasawara J, et al. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider P, et al. Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1205–1213. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varfolomeev EE, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, FAS/APO1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen G. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J. 1997;326:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monney L, et al. Role of an acidic compartment in tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha-induced production of ceramide, activation of caspase-3 and apoptosis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;251:295–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heuman D, Bajaj R. Ursodeoxycholate conjugates protect against disruption of cholesterol-rich membranes by bile salts. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]