Abstract

Background

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of deep brain stimulation (DBS) has potentials to reveal neuroanatomical connectivity of a specific brain region in vivo.

Objective

This study aimed to demonstrate frequency and amplitude tunings of the thalamocortical tract using DBS fMRI at the rat ventral posteromedial thalamus.

Methods

Blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) fMRI (n=12) data were acquired in rats at a high-field 11.7T MRI scanner with modulation of nine stimulus frequencies (1–40 Hz) and seven stimulus amplitudes (0.2–3.6 mA).

Results

BOLD response in the barrel cortex peaked at 25 Hz. The response increased with stimulus amplitude and reached a plateau at 1 mA. Cortical spreading depolarization (CSD) was observed occasionally after DBS that carries >10% BOLD waves spanning the entire ipsilateral cortex.

Conclusion

fMRI of DBS has potential to explore and validate functional connectivity in the brain, study DBS treatment effect, and investigate the spatiotemporal characteristics of the CSD.

Keywords: striatum, Deep brain stimulation, fMRI, thalamus, rat, isoflurane

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is clinically used to treat several neurological symptoms such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia (1, 2). The underlying mechanisms remain however largely unexplored. DBS efficacy in the brain has been studied primarily by electrophysiology recording, which does not provide depth-resolved mapping of DBS responses on a whole brain scale. Blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides noninvasive, in vivo measurement of cerebral neurovascular function and has potentials to study whole brain responses to real-time DBS.

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate thalamocortical connectivity under different frequency and amplitude tunings in rats and establish a DBS fMRI protocol under isoflurane anesthesia that allows longitudinal study. BOLD fMRI (n = 12) data were acquired on an 11.7T MRI scanner with modulation of nine stimulus frequencies (1, 3, 7, 11, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 40 Hz fixed at 1 mA and corresponding pulse widths of 1/frequency ms) and seven stimulus amplitudes. (0.2, 0.6, 1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.8, and 3.6 mA fixed at 7 Hz and 1/7 ms pulse width). Ventral posteromedial (VPM) thalamus was selected due to its rich innervation to the cortex. We hypothesized that the barrel cortex can be reliably activated by DBS and the responses exhibit frequency and amplitude-dependent properties. This approach has potential to explore/validate functional connectivity in the brain and study DBS treatment effect in normal and diseased animal models.

Material and Methods

Subjects

A total of 12 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (weighing 250–300 g; Charles River Laboratories) were studied. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional of Animal Care and Utilization Committee, UT Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Animal preparation

Rats were initially anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and orotracheally intubated for mechanical ventilation (Model 683, Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA). After the animal was secured in a MRI compatible rat stereotaxic headset, isoflurane was reduced to 1–1.2%. End-tidal CO2 was continuously monitored via a capnometer (Surgivet, Smith Medical, Waukesha, WI). Non-invasive end-tidal CO2 values were previously calibrated against invasive blood-gas samplings under identical conditions (3, 4). Rectal temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5 °C with warm-water circulating pad. Heart rate and blood oxygen saturation level were continuously monitored by a MouseOx system (STARR Life Science Corp., Oakmont, PA). All recorded physiologic parameters were maintained within normal ranges. A two-channel twisted platinum microelectrode (MS303/9C-B, PlasticsOne, Roanoke, VA) with 156 µm wire diameter was implanted into the VPM thalamusa at 3 mm posterior to the bregma, 3 mm lateral to the midline, 6 mm below the cortical surface (5), and fixed with dental cement.

Stimulation

Stimulation pulses were generated by a custom-written software with a multifunctional USB module (USB-1208HS-2AO, Measurement Computing, Norton, MA) offering a digital-to-analog conversion rate of 1 MS/s to trigger an isolated current stimulator (A365, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Stimulus current was carried by a 2 channel twisted cable (305–491/2 with mesh, PlasticsOne, Roanoke, VA) with a home-made silver wire extension to the DBS electrode. In the first study, modulation of nine stimulus frequencies (1, 3, 7, 11, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 40 Hz fixed at 1 mA and corresponding pulse widths of 1/frequency ms) were studied (number of subjects = 12). The pulse-width was calibrated to ensure the total amount of charge delivered into the brain tissue per second was identical across different frequencies. In the second study, modulation of seven stimulus amplitudes (0.2, 0.6, 1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.8, and 3.6 mA fixed at 7 Hz and 1/7 ms pulse width) were studied (number of subjects = 7). These parameters were chosen based on a pilot study designed by the authors that explored potential frequency and amplitude dependent responses, by which apparent modulation of fMRI signal can be observed. Frequency of 20–30 Hz has been widely used for whisker stimuli experiments [ref]. The stimulus parameters were randomized for both studies. Stimulation paradigm was OFF-ON-OFF-ON-OFF, where OFF = 100 s and ON = 50 s.

fMRI experiments

fMRI data were acquired on a 11.7 T, 16 cm bore magnet and a 74 G/cm gradient insert (Bruker, Billerica, MA). A custom-made circular surface coil (ID~2 cm) was placed on the rat head. Magnetic field homogeneity was optimized using standard FASTMAP shimming on an isotropic voxel of 7×7×7 mm. A T2-weighted pilot image was taken in the mid-sagittal plane to localize the anatomical position by identifying the anterior commissure (bregma −0.8 mm). BOLD fMRI was acquired with 4-shot gradient-echo EPI sequence using spectral width = 200 kHz, TR/TE = 1250/12 ms, FOV = 2.56×2.56 cm, slice thickness = 1 mm, matrix = 128×128, and temporal resolution = 5 s. Repeated scans were performed when CSD occurred.

Data analysis

Image analysis was performed using a custom-written graphic user interface (6, 7) in Matlab (Math-Works, Natick, MA) and Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM). Time series MRI data were co-registered to align image drift overtime using the spatial realignment function in SPM5 when needed. Percent BOLD activation map was generated by comparing the signal before and during stimulation with a significant threshold of P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected). Region of interests (ROIs) were placed on the barrel cortex to extract fMRI time-course data. Dynamic cine analysis was used to delineate CSD propagation. The color-coded pixel values at each time frame were formed by subtracting the mean map of the pre-stimulus period, and the threshold was set as a 3% BOLD signal increase from the baseline. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Repeated-measures ANOVA with LSD post-hoc test was used to compare stimulus-evoked BOLD signal changes at different stimulus conditions. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

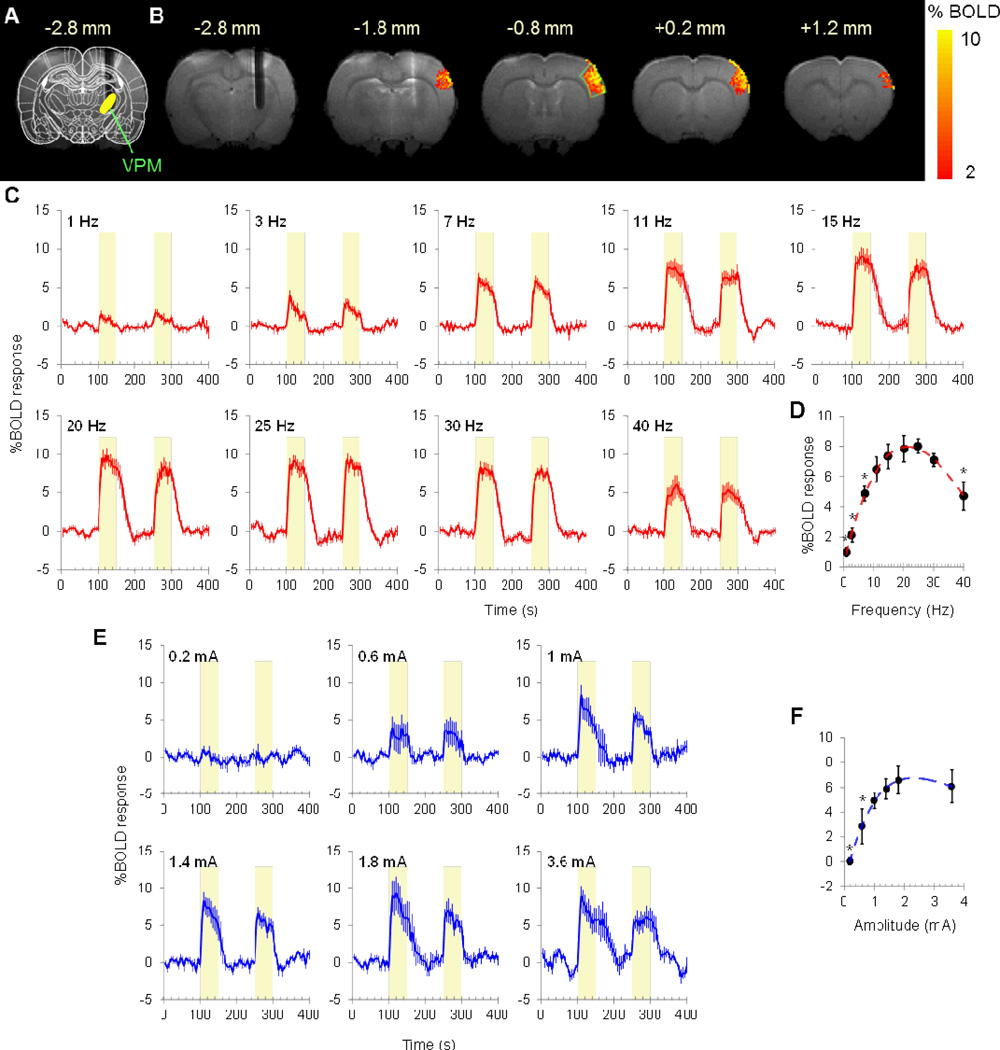

MR image with an overlaid of a brain atlas showed the electrode tract. The size of electrode artifactually appeared larger due to susceptibility effect (Figure 1A). Representative BOLD fMRI maps evoked by 20 Hz DBS are shown in Figure 1B. The activations are mainly located in the S1 barrel field and the upper lip region, which are known to be highly innervated by VPM neurons. No apparent spatial shift was observed at different stimulus parameters throughout the study. In the first study (modulation of nine frequencies), averaged BOLD fMRI time courses at 1–40 Hz stimuli are shown in Figure 1C. BOLD responses in the barrel cortex exhibited a bell-shaped tuning curve peaked at 25 Hz (Figure 1D). Compared to the 25 Hz data, significantly lower BOLD responses were observed at 1, 3, 7, and 40 Hz (P < 0.05), and no significant differences were detected at 11, 15, 20, and 30 Hz (P > 0.05). BOLD responses showed robust activation with high contrast-to-noise ratio (up to 8% BOLD at 11.7 T). In the second study (modulation of six amplitudes), averaged BOLD fMRI time courses at 0.2–3.6 mA stimuli are shown in Figure 1E. BOLD responses increased with stimulus amplitude and reached a plateau at 1 mA.

Figure 1.

DBS fMRI with stimulus frequency modulation. (A) Rat brain atlas overlaid on an anatomy (Bregma −2.8 mm), showing the position of the microelectrode. (B) BOLD activation maps of a representative subject. Responses were mainly located in the S1 barrel field/upper lip region. ROI was placed at −0.8 mm. (C) Grand-averaged BOLD responses to 9 stimulus frequencies. Yellow-shaded area indicates stimulus epoch. (D) BOLD responses exhibited a frequency-dependent pattern peaked round 25 Hz. *P<0.05, different from peak value.

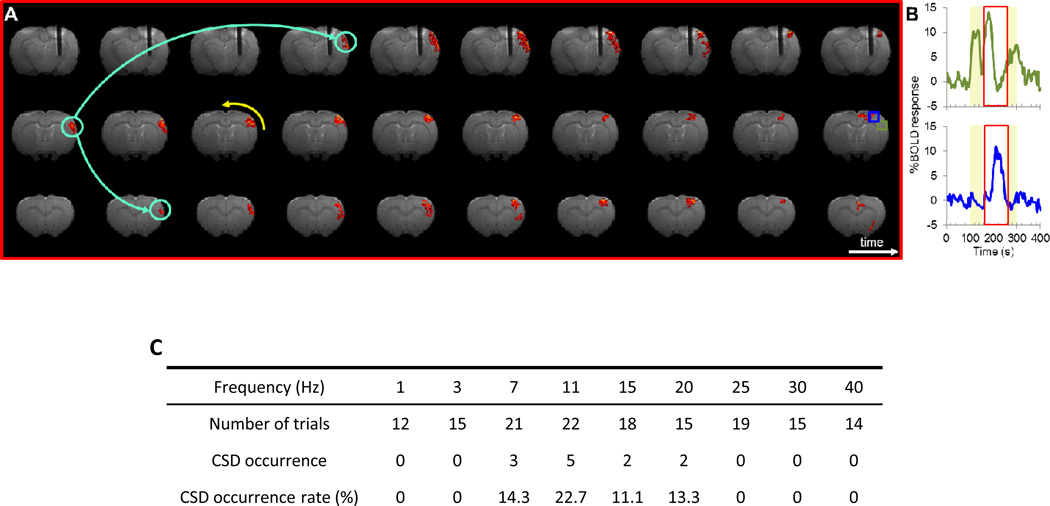

Cortical spreading depolarization was observed occasionally after the DBS (12 times out of 151 trials) that carries >10% BOLD waves spanning the entire ipsilateral cortex (Figure 2). The CSD usually initiated 1 min after the stimulus onset, propagated toward the midline, anterior, and posterior part of the cortex with an estimated speed at ~4 mm/min. Among all trials, the depolarization waves never crossed the hemisphere and only stayed in the cortex.

Figure 2.

DBS induced spreading depolarization. (A) The CSD initiated in the barrel cortex, propagated toward the midline and spread in both anterior and posterior directions. (B) fMRI time-course data from two ROIs from (A). The red window between two timulus epochs indicates the temporal span of (A).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that fMRI of DBS evoking robust functional response in the rat barrel cortex under isoflurane anesthesia. BOLD response in the barrel cortex exhibited a tuning curve that peaked at 25 Hz. Modulation of amplitude showed that the signals reached a plateau at 1 mA.

By systemically evaluating 9 frequencies and 7 pulse widths, we showed that up to 8% BOLD signal changes can be detected at 11.7T. No obvious lesion was observed in the T2*-weighted images up to 3.6 mA. The subsequent trials also evoked robust and repeatable fMRI responses, indicating the VPM neurons were not damaged at this current amplitude when a short pulse width (1/7 ms) was applied. However, a single pulse of 0.1 mA with 5 s pulse width produced observable lesion in the T2*-weighted images (data not shown), suggesting cautions on using DBS with long pulse width and highlighting the importance of DBS parameter calibration. BOLD response in VPM was not observed because of the susceptibility artifact induced by the commercial electrode. With proper selection of electrode materials, local BOLD responses may be seen [Lai]. Of note, the cortical BOLD response could originate from stimulating thalamocortical cells, or antidromically stimulating corticalthalamic afferent terminals [Grill]. Further elucidation using c-fos or optogenetics is warranted.

One potential limitation of the present study is that animals were anesthetized during DBS sessions. Anesthesia is known to alter peak frequency when peripheral sensory stimulus was performed [ref]; however, recent pilot study showed that animals under α-chloralose and isoflurane anesthesia exhibit similar frequency-dependence and location of BOLD response, indicaiting that anesthesia may have less impact on DBS fMRI. A possible explanation is that DBS bypassed the anesthetic confounds on the peripheral nervous system and ascending neurons in the spinal cord.

In summary, the present study demonstrated thalamacortical connectivity by stimulating VPM thalamus in rats. This fMRI response was highly frequency-dependent. We also demonstrated that DBS can induce CSD-like signals. This study demonstrates the feasibility of measuring DBS frequency-dependent response during fMRI. The procedure established herein could serve as the basis of a wide variety of system neuroscience applications, such as mapping DBS treatment effect in Parkinsonian animal models or evaluating plasticity changes of thalamocortical tract following injury [ref]. This work also provides important information regarding the selection of DBS parameter for future fMRI studies in animal models.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported in part by the American Heart Association (10POST4290091), Clinical Translational Science Awards (CTSA, parent grant UL1RR025767), and San Antonio Area Foundation to Dr. Yen-Yu Ian Shih and the NIH/NINDS R01 NS45879 and VA MERIT to Dr. Timothy Q Duong.

References

- 1.McIntyre CC, Savasta M, Kerkerian-Le Goff L, Vitek JL. Uncovering the mechanism(s) of action of deep brain stimulation: activation, inhibition, or both. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(6):1239–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano Andres M, Lipsman N. Probing and Regulating Dysfunctional Circuits Using Deep Brain Stimulation. Neuron. 2013;77(3):406–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih YY, Wang L, De La Garza BH, Li G, Cull G, Kiel JW, et al. Quantitative retinal and choroidal blood flow during light, dark adaptation and flicker light stimulation in rats using fluorescent microspheres. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38(2):292–298. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.756526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih YY, Li G, Muir ER, De La Garza BH, Kiel JW, Duong TQ. Pharmacological MRI of the choroid and retina: Blood flow and BOLD responses during nitroprusside infusion. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(4):1273–1278. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih YY, Chen YY, Chen JC, Chang C, Jaw FS. ISPMER: Integrated System for Combined PET, MRI, and Electrophysiological Recording in Somatosensory Studies in Rats. Nucl Instrum Meth A. 2007;580(2):938–943. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih YY, Chen YY, Chen CC, Chen JC, Chang C, Jaw FS. Whole-brain functional magnetic resonance imaging mapping of acute nociceptive responses induced by formalin in rats using atlas registration-based event-related analysis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(8):1801–1811. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim T, Masamoto K, Fukuda M, Vazquez A, Kim SG. Frequency-dependent neural activity, CBF, and BOLD fMRI to somatosensory stimuli in isoflurane-anesthetized rats. NeuroImage. 2010;52(1):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masamoto K, Kim T, Fukuda M, Wang P, Kim SG. Relationship between neural, vascular, and BOLD signals in isoflurane-anesthetized rat somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(4):942–950. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanganahalli BG, Herman P, Hyder F. Frequency-dependent tactile responses in rat brain measured by functional MRI. NMR Biomed. 2008;21(4):410–416. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreier JP. The role of spreading depression, spreading depolarization and spreading ischemia in neurological disease. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]