Abstract

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are battery-powered nicotine delivery devices that have become popular among smokers. We conducted an experiment to understand adult smokers’ responses to e-cigarette advertisements and investigate the impact of ads’ arguments and imagery.

Methods

A US national sample of smokers who had never tried e-cigarettes (n=3253) participated in a between-subjects experiment. Smokers viewed an online advertisement promoting e-cigarettes using one of three comparison types (emphasising similarity to regular cigarettes, differences or neither) with one of three images, for nine conditions total. Smokers then indicated their interest in trying e-cigarettes.

Results

Ads that emphasised differences between e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes elicited more interest than ads without comparisons (p<0.01), primarily due to claims about e-cigarettes’ lower cost, greater healthfulness and utility for smoking cessation. However, ads that emphasised the similarities of the products did not differ from ads without comparisons. Ads showing a person using an e-cigarette created more interest than ads showing a person without an e-cigarette (p<0.01).

Conclusions

Interest in trying e-cigarettes was highest after viewing ads with messages about differences between regular and electronic cigarettes and ads showing product use. If e-cigarettes prove to be harmful or ineffective cessation devices, regulators might restrict images of e-cigarette use in advertising, and public health messages should not emphasise differences between regular and electronic cigarettes. To inform additional regulations, future research should seek to identify what advertising messages and features appeal to youth.

Keywords: Electronic nicotine delivery devices, Non-cigarette tobacco products, Advertising and Promotion

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes, also called e-cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems, are battery-powered devices that heat cartridges, which typically contain nicotine and humectants, to create a vapour that the user inhales. There are many varieties: disposable versus refillable, with or without nicotine, and flavoured (eg, menthol or chocolate) versus unflavoured. E-cigarettes are controversial. The scientific community is concerned about safety,1–3 the product's use as a ‘gateway’ to other tobacco products4 and the possibility of renormalising smoking.5 At the same time, e-cigarettes are a non-combustible product that could meet some of the needs of nicotine-addicted smokers and thus hold the potential to be a valuable harm reduction tool for smokers who switch.6 Many e-cigarette users also claim that e-cigarettes helped them quit smoking.7 8 Longitudinal studies and large surveys are inconsistent in supporting this claim.9–11 The one randomised controlled trial that compared e-cigarettes with another nicotine replacement therapy did not find a difference between cessation rates for e-cigarettes versus the nicotine patch.12

Despite the controversy, e-cigarettes are increasingly popular. Use is particularly high among smokers,13–15 with 32% of smokers in 2012 and 50% of smokers in 2013 reporting having ever tried e-cigarettes.15 16 The glut of e-cigarette advertising could be contributing to e-cigarettes’ rise in popularity. Greater exposure to cigarette advertising predicts greater likelihood of smoking initiation.17 18 By extension, exposure to e-cigarette advertising may prompt people to start using e-cigarettes. Smokers appear to respond positively to such ads. In a recent study, two-thirds of smokers who watched a television ad for Blu e-cigarettes indicated interest in trying e-cigarettes after watching the ad, although this study did not use an experimental protocol or measure interest prior to exposure.19 While we cannot draw a causal inference, rates of use of e-cigarettes have risen13 15 20 in tandem with increases in e-cigarette advertising.21–23

Television, radio and print ads and other forms of e-cigarette marketing aimed at smokers often compare e-cigarettes with regular cigarettes.21 22 24 Ads describe e-cigarettes as newer, healthier, cheaper and easier to use in smoke-free situations, all reasons that e-cigarette users claim motivate their use.15 20 Advertisers also promote e-cigarettes as a cessation tool, although they often use indirect methods like affiliate marketing25 26 in order to avoid violating a 2010 US district court decision that blocked such claims.27 Some ads also highlight how e-cigarette use mimics the positive aspects of smoking regular cigarettes, that is, the social experience or satisfaction.21

Smokers’ responses to different ads may depend on how they view the comparison between the novel or innovative product (ie, e-cigarettes) and the traditional one (ie, regular cigarettes). Unique features of new nicotine products might be attractive in ways that will encourage use.28 Commentary and theory regarding the diffusion of innovation is useful in this regard as it suggests that adoption of a new technology is faster when the innovation embodies certain key characteristics.29 First, innovations that spread quickly have a relative advantage over the object they are replacing (eg, e-cigarettes cost less than cigarettes). Second, popular innovations are compatible with the values, experiences and needs of the adopter (eg, using e-cigarettes feels the same as smoking).

Our study sought to better understand the potential for advertising to facilitate diffusion of e-cigarettes to current cigarette smokers. We conducted an experiment testing advertising messages that focus on differences between e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes (ie, relative advantage) and similarities of the two products (ie, compatibility). The specific messages we chose to include in these ads are typical messages found in e-cigarette advertising, as shown in recent content reviews.21–23 Based on our observation that many e-cigarette ads depicted a person using an e-cigarette, we also aimed to understand why such ads might be particularly persuasive. We chose three images (a woman using an e-cigarette, a man not using an e-cigarette and an e-cigarette kit) to determine which feature of the ad (that it showed a person, the product or a person interacting with the product) produced the greatest interest.

We predicted that ads emphasising the differences (ie, relative advantages) between e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes would elicit more interest in trying e-cigarettes than control ads, as many smokers view cigarettes as unhealthy,30 are aware of the substantial stigma attached to smoking31 32 and want to quit.33 We expected less benefit of ads emphasising their similarities (ie, compatibility), as smoking is a stigmatised activity even among smokers.32 We also predicted that smokers would be more interested in trying e-cigarettes when shown an ad depicting a person using an e-cigarette compared with ads with other images. Images of smoking cause cravings among smokers,34 35 so seeing someone use a similar-looking product could elicit desire to use the product.

Methods

Sample

In March 2013, 17 522 US adult (age 18 or older) smokers and non-smokers completed an online survey as part of the Tobacco Control in a Rapidly Changing Media Environment study. Seventy-five per cent of respondents came from KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative online survey panel constructed using random digit dialling supplemented by address-based sampling to account for cell phone-only households. A convenience sample of adults who responded to online ads comprised the remaining 25%; the survey company screened their names and addresses, removed duplicates and quota matched to the probability sample based on demographics and tobacco use characteristics. Of the 34 097 KnowledgePanel members sampled, 61% completed the screening, and 97% of those who were eligible completed the online survey. Response rate data for the convenience samples are not available because there is no known sampling frame. For this study, we report data from current smokers (those who reported smoking every day or some days) who had never tried e-cigarettes (n=3253). All participants provided consent online before beginning the survey. Institutional review boards at the National Cancer Institute and the University of Illinois at Chicago approved the study.

Procedures

We randomly assigned participants to one of nine conditions in a 3 (image in ad)×3 (type of comparison) between-subjects factorial experiment. An advertising agency designed the ads (see sample ads in the online supplementary material) with a mock e-cigarette brand, ‘Evermist e-cigs’. The ad image showed a person using an e-cigarette (a woman using an e-cigarette with a red glowing tip), a rechargeable e-cigarette kit or no e-cigarette (a man looking at a laptop computer screen). Each ad had one of three headlines, which indicated a comparison type (difference, similarity or neither (ie, control)). The difference ads had the headline, “Better than a cigarette”, accompanied by one of four ad messages (costs less, use anywhere, healthier and helps to quit smoking) that emphasised the differences between the products. The similarity ads had the headline, “Just like a cigarette”, accompanied by one of three ad messages (feels the same as smoking, relieves your cravings and still smoke with friends) that emphasised the similarities between e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes. The control ads (no comparison) had the headline, “E-cigarettes”, accompanied by a message (great to use) that did not emphasise differences similarities or differences.

Measures

While viewing the ad, participants responded to the item, “How much does seeing this ad make you want to try e-cigarettes?” using a five-point scale (‘not at all’ (coded as 1), ‘a little bit’ (2), ‘a moderate amount’ (3), ‘quite a bit’ (4) and ‘a great deal’ (5)).

Data analysis

To check whether random assignment created demographically equivalent groups by comparison type (similarity, difference and control), we used χ2 tests for categorical demographic variables (gender, education, race/ethnicity, employment status and income) and linear regression for the continuous demographic variable (age). We repeated these tests for ad message and for the other experimental manipulation, ad image.

We examined the effects of the experimental manipulations on interest in trying e-cigarettes using a 3×3 ANOVA. The factors were comparison type and ad image. As the interaction was not statistically significant (p=0.20), we repeated the ANOVA model without the interaction term. We used a Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. We also used ANOVA to confirm that there was no interaction between the experimental manipulations and the sampling method (ie, whether the experimental findings differed for respondents recruited through convenience vs probability sampling) (p>0.05 for both interactions). For descriptive purposes, we conducted a linear regression to determine if interest in trying e-cigarettes varied by the specific ad message (relieves cravings, costs less, etc) using the control message (great to use) as the reference category. We also conducted an ANOVA testing a possible interaction between specific ad message and image on interest in trying e-cigarettes. The interaction was not significant (p=0.36), so we do not report it here.

Data are not weighted because of the experimental design. Analyses with Stata V.12 used two-tailed statistical tests and a critical α of 0.025 for the ANOVA and 0.05 for the linear regression.

Results

The majority of participants were female (59%) and non-Hispanic white (77%) and had at least some college education (67%) and an annual household income less than $50 000 (62%) (table 1). About half (48%) were currently working, and the mean age was 50 years (SD 15 years). Fifty-one per cent intended to quit smoking in the next year and 14% more than 1 year from now, while 35% did not intend to quit smoking. Demographic characteristics of participants were equivalent across experimental conditions (all p>0.05, see online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n=3253)

| n | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1347 | 41.4 |

| Female | 1906 | 58.6 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 49.6 (14.7) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 174 | 5.3 |

| High school | 897 | 27.6 |

| Some college | 1363 | 41.9 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 819 | 25.2 |

| Intention to quit smoking | ||

| In the next year | 1668 | 51.3 |

| More than 1 year from now | 440 | 13.5 |

| Do not plan to quit | 1145 | 35.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2506 | 77.0 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 315 | 9.7 |

| Non-Hispanic, other or multiple races | 199 | 6.1 |

| Hispanic | 233 | 7.2 |

| Employment | ||

| Working | 1563 | 48.0 |

| Not working: laid off or looking for work | 393 | 12.1 |

| Not working: retired, disabled, or other | 1297 | 39.9 |

| Household | ||

| Annual household income | ||

| Less than $25 000 | 1035 | 31.8 |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 982 | 30.2 |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 618 | 19.0 |

| $75 000–$99 999 | 341 | 10.5 |

| $100 000 or more | 277 | 8.5 |

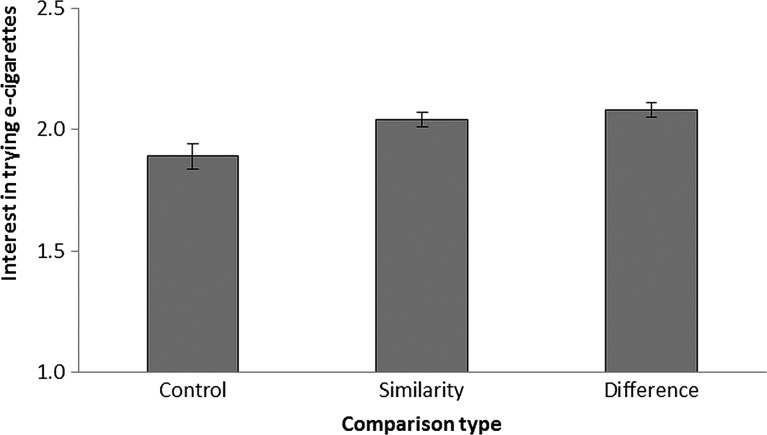

Interest in trying e-cigarettes varied by comparison type (F (2, 3248)=3.94, p<0.025). One type of comparison ad generated effects on viewer interest: ads that emphasised the differences between cigarettes and e-cigarettes (mean interest 2.08) created more interest than control ads (mean 1.89, p<0.05) (table 2; figure 1). The other type of comparison ad did not generate such differences: smokers reported similar interest in trying e-cigarettes after viewing control ads and ads that emphasised similarity (mean 2.04, p=0.06).

Table 2.

Interest in trying e-cigarettes, by ad characteristics

| Comparison type | Ad headline | Mean (SD) | Ad message | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | E-cigarettes | 1.89 (1.10) | ||

| Great to use | 1.89 (1.10) | |||

| Similarity | Just like a cigarette | 2.04 (1.17) | ||

| Feels like smoking | 1.99 (1.14) | |||

| Relieves cravings | 2.05 (1.14) | |||

| Use with friends | 2.09 (1.23)* | |||

| Difference | Better than a cigarette | 2.08 (1.19)** | ||

| Use anywhere | 2.04 (1.22) | |||

| Helps you quit | 2.06 (1.12)* | |||

| Costs less | 2.09 (1.20)** | |||

| Healthier | 2.12 (1.23)** |

Note: Higher means indicate greater interest in trying e-cigarettes (1=not at all—5=a great deal).

Comparison to control headline/message *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Figure 1.

Effect of comparison type on interest in trying e-cigarettes. Error bars show standard errors.

As for the specific comparison claims, advertisements elicited greater interest in trying e-cigarettes when they had messages stating that e-cigarettes differed from regular cigarettes because they were healthier than cigarettes (mean 2.12, p<0.01), were less expensive than cigarettes (2.09, p<0.05) or were helpful to quit smoking (2.06, p<0.05) as compared with the control message (1.89) (table 2). Interest in trying e-cigarettes was also higher when the ad stated that e-cigarettes were similar to cigarettes because they could be used with friends (2.09, p<0.05) compared with an advertisement with a control message. The other three experimental messages elicited equivalent interest as the control message.

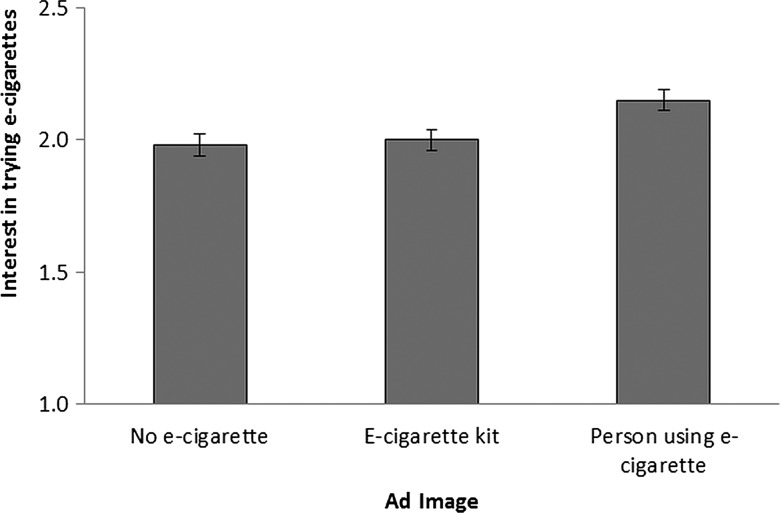

Interest in trying e-cigarettes also varied by ad image (F (2, 3248)=6.95, p<0.01). Ads showing a person using an e-cigarette (mean 2.15) created more interest than ads not showing an e-cigarette (mean 1.98, p<0.01), but there was no difference between ads showing an e-cigarette kit (mean 2.00) and ads not showing an e-cigarette (p>0.99) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of advertisement image on interest in trying e-cigarettes. Error bars show standard errors.

Discussion

Smokers expressed moderate interest in trying e-cigarettes after viewing the advertisements, but their level of interest varied as a function of comparison type, message and image. The type of promotional strategy used made a significant difference as to whether an e-cigarette ad generated interest among smokers. The depiction of people actually using the new product and comparisons that emphasised differences between e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes appeared to have important effects.

Consistent with our prediction, interest was higher among respondents who viewed difference-focused ads compared with the control ad. As a relatively new entry to the US market, e-cigarettes are innovative tobacco products. Although both relative advantage and compatibility enhance the likelihood that an innovation will be adopted,29 the old product in this instance, namely, regular cigarettes, is stigmatised and unattractive.31 32 Indeed, most smokers want to quit.33 Thus, the innovative tobacco product was more attractive when framed as different from the original, while similarity messages had little or no impact.

The specific ad messages associated with the greatest amount of interest described e-cigarettes’ healthfulness, cost, use as a quit tool and the social experience of use. That responses to messages about health and cessation were more positive than responses to other messages is consistent with the literature, as e-cigarette users frequently report these as reasons for use.20 In prior survey research, e-cigarettes’ cost relative to cigarettes appears to motivate trying the product, although some users find the product to be more expensive than anticipated and may even discontinue use for this reason.20 36 37 Although the social experience of using with friends is not as frequently mentioned by current e-cigarette users, it may be that this factor created some of their initial interest in trying the product, as was found here, but did not impact their continued use.

That the message ‘relieves your cravings’ was unrelated to interest is not surprising as research on smokers’ subjective and objective experiences show large variability in e-cigarettes’ ability to deliver a satisfactory amount of nicotine.7 38–40 Smokers may be aware of this issue if they have discussed e-cigarettes with other smokers who have tried them. Indeed, smokers say that e-cigarette users are their most frequent source of information about the product.41 The message that e-cigarettes can be used anywhere was also not particularly attractive to smokers. This result could reflect a social desirability bias: perhaps smokers did not want to admit that they wish to skirt popular restrictions on smoking.42 43 It could also reflect that smokers did not believe the e-cigarettes could indeed be used in this way because of new laws or restrictions or complaints from other people.44 45 Unlike the claim ‘use with friends’, which smokers may have actually experienced in their personal lives, the claim ‘use anywhere’ (emphasis ours) is something that they likely know is not objectively true.

The ads that depicted a woman using an e-cigarette were more popular than the ads showing an e-cigarette kit or a man with a laptop. Although we cannot rule out that the increased interest was because of the attractive woman, we suspect that it reflects a type of cross-cue reactivity. As described in the cue reactivity literature, smokers experience cravings when they see images of smoking.34 35 In this case, viewing the image of e-cigarette use may also have served as a subliminal cue for craving, which thus increased interest in trying a cigarette-like product. Smokers did not respond this way to the image of the e-cigarette kit not in use, possibly because this image showed a battery charger and tray of cartridges, which make the e-cigarette look less like a regular cigarette. Social learning theory46 also suggests that seeing someone use an e-cigarette models the behaviour, which could motive interest and, later, use.

Our findings have implications for both regulation and public health messaging. If ongoing research finds that e-cigarette use causes health problems or deters significant numbers of smokers from quitting, the public health community will need to discourage e-cigarette use among adult smokers. Future public health campaigns likely would need to use materials that do not show the product being used as this appears to be related to increased interest. One editorial recently suggested banning television ads that show smoking behaviour, regardless of what product is being smoked.47

The potential effects of advertising on e-cigarette use are concerning. While e-cigarettes produce fewer harmful emissions than regular cigarettes,48 they are not harm free. Moreover, if non-smokers or youth begin using e-cigarettes or if smokers use e-cigarettes in lieu of quitting, there may be a net harm at the population level even if there is a benefit for an individual smoker. Brazil and other countries have banned e-cigarette advertising and the European Union will follow suit beginning in mid-2016.49 50 If specific claims are unproven (eg, e-cigarettes help smokers quit or e-cigarettes have zero toxins), they should not be allowed in advertising even if e-cigarette advertising as a whole is not banned.

Regulations restricting e-cigarette advertising features that appeal to youth are also critical, particularly given the history of marketing regular cigarettes. Camel's Old Joe campaign successfully promoted that brand to youth in the USA,51 and in 1991, the same proportion (over 90%) of 6-year-old children recognised the Old Joe logo as recognised the Disney logo.52 The 1997 Master Settlement Agreement prevented tobacco companies from using cartoon characters or otherwise targeting youth under age 18 in their advertising. We do not yet know what e-cigarette advertising features or logos will be compelling to young people or the extent to which those features will motivate e-cigarette experimentation. Should future studies like this one find that certain ad design features (eg, cartoons) appeal to youth, regulations should limit those features. Research in this area is particularly important given the potentially strong appeal of candy-flavoured and fruit-flavoured e-cigarettes to children.

Limitations to this study include the use of a psychosocial but not behavioural outcome measure. In addition, the majority of experiment participants were recruited through online convenience sampling, which limits the generalisability of the findings to the entire US adult population, although we confirmed that our findings did not differ by sampling method. The experiment elicited relatively small effects; however, given that there were 42 million adult smokers in the USA in 2012,53 small effects could still result in meaningful real-world changes.54

We chose to design new ads, instead of modifying existing ads, because we sought to exert greater experimental control than existing ads would permit. By working with an ad agency to design new ads, we were able to maintain the maximum amount of control when varying characteristics (eg, the ability to change the image without impacting other aspects of the layout). However, these new ads may not have matched the ‘feel’ or effectiveness of real-world ads. Future studies might incorporate real ads to increase the external validity of findings and also use ads with several images, including males using e-cigarettes. In our study, we could not conclude whether smokers were more interested in trying e-cigarettes when shown an image of a woman using an e-cigarette because they thought the specific woman depicted was attractive or because she was engaging in a smoking-like behaviour. We also did not explore non-smokers’ responses to the ads and did not include a ‘no ad’ condition to establish interest in trying e-cigarettes in the absence of an advertisement.

Finally, one critique of much work in research on communication is that intention to perform a behaviour does not necessarily lead to that behaviour. While the intention-behaviour gap is well documented in many areas, intentions remain a strong predictor of behaviour.55 Of course, we believe that this gap should not deter regulatory authorities from instituting appropriate restrictions on e-cigarette advertising. Despite these limitations, the data are compelling and useful for future investigations of new e-cigarette marketing. The randomised design and large national sample are key strengths of the study.

E-cigarettes are a big—and rapidly growing—business. In 2013, sales of e-cigarettes were nearly $2 billion, and sales are likely to rise to $10 billion by 2017.56 Multinational tobacco companies are entering the e-cigarette market by buying existing companies or developing their own products. The involvement of these companies will likely increase the amount, reach and sophistication of e-cigarette advertising,21 22 24 and recent research suggests that exposure to e-cigarette advertising is associated with interest in trying the product.19 57 With the new evidence presented in this paper, it is clear that specific types of messages used to promote e-cigarettes are more effective in soliciting interest among current smokers who have yet to try e-cigarettes. Armed with such evidence, public health professionals can monitor e-cigarette marketing across a variety of channels and consider what claims and imagery regulations should address.

What this paper adds.

Although e-cigarette advertising is increasingly prevalent, little research has examined the impact of ads on interest in trying e-cigarettes.

This experiment, based on the diffusion of innovations framework, found that ads depicting the use of e-cigarettes or including messages that emphasised the differences between regular and electronic cigarettes were associated with greater interest among adult smokers in trying e-cigarettes.

Regulatory agencies may wish to restrict advertisements with features that elicit smokers’ interest in order to discourage e-cigarette use.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceptualised the design of the experiment. JKP and SLE collected the data. JKP analysed the data and wrote the initial manuscript with assistance from NTB. All authors provided substantive edits and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (UO1CA154254) and the UNC Lineberger Cancer Control Education Program (R25 CA57726).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: IRB at University of Illinois at Chicago and at the National Caner Institute.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Evaluation of e-cigarettes , 2009. Contract No.: DPATR-FY-09-23.

- 2.Bahl V, Lin S, Xu N, et al. Comparison of electronic cigarette refill fluid cytotoxicity using embryonic and adult models. Reprod Toxicol 2012;34:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HJ, Shin HS. Determination of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in replacement liquids of electronic cigarettes by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr 2013;1291:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: a new nicotine gateway? J Adolesc Health 2013;52:135–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell K, Keane H. Nicotine control: e-cigarettes, smoking and addiction. Int J Drug Policy 2012;23:242–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams DB. Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete?. JAMA 2014;311:135–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction 2011;106:2017–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbeau AM, Burda J, Siegel M. Perceived efficacy of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy among successful e-cigarette users: a qualitative approach. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2013;8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasza KA, Bansal-Travers M, O'Connor RJ, et al. Cigarette smokers’ use of unconventional tobacco products and associations with quitting activity: findings from the ITC-4, U.S. cohort. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:672–81.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: a national study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etter JF, Bullen C. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette users. Addict Behav 2014;39:491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control 2013;22:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, et al. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu SH, Gamst A, Lee M, et al. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the U.S. population. PloS one 2013;8:e79332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emery S. It's not just message exposure anymore: a new paradigm for health media research. Presented at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Baltimore, MD, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capella ML, Webster C, Kinard BR. A review of the effect of cigarette advertising. Int J Res Mark 2011;28:269–79. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Insititute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19 Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, et al. Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions, and beliefs: a systematic review. Tob Control 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K, et al. The marketing of electronic cigarettes in the UK. A report commissioned by Cancer Research UK. London, UK: Cancer Research UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson A, Ganz O, Stalgaitis C, et al. Noncombustible tobacco product advertising: how companies are selling the new face of tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K. Promotion of electronic cigarettes: tobacco marketing reinvented? BMJ 2013;347:f7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobb NK, Brookover J, Cobb CO. Forensic analysis of online marketing for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paek HJ, Kim S, Hove T, et al. Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? Source, message, and information characteristics of e-cigarette videos on YouTube. J Health Commun 2014;19:545–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smoking Everywhere, Inc., Plaintiff, and Sottera, Inc., d/b/a NJOY, Intervenor-Plaintiff v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, et al., Defendents: United States District Court for the District of Columbia, 2010.

- 28.Southwell BG, Kim AE, Tessman GK, et al. The marketing of dissolvable tobacco: social science and public policy research needs. Am J Health Promot 2012;26:331–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th edn. New York, NY: Free Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstein ND. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perceptions. Ann Behav Med 1998;20:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SH, Shanahan J. Stigmatizing smokers: public sentiment toward cigarette smoking and its relationship to smoking behaviors. J Health Commun 2003;8:343–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie D, Amos A, Martin C. “But it just has that sort of feel about it, a leper”—stigma, smoke-free legislation and public health. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:622–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR 2011;60:1513–19.22071589 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders-Jackson AN, Cappella JN, Linebarger DL, et al. Visual attention to antismoking PSAs: smoking cues versus other attention-grabbing features. Hum Commun Res 2011;37:275–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S, Cappella JN. Distraction effects of smoking cues in antismoking messages: examining resource allocation to message processing as a function of smoking cues and argument strength. Media Psychol 2011;13:282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQueen A, Tower S, Sumner W. Interviews with “vapers”: implications for future research with electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kralikova E, Kubatova S, Truneckova K, et al. The electronic cigarette: what proportion of smokers have tried it and how many use it regularly? Addiction 2012;107:1528–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eissenberg T. Electronic nicotine delivery devices: ineffective nicotine delivery and craving suppression after acute administration. Tob Control 2010;19:87–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vansickel AR, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawkins L, Turner J, Hasna S, et al. The electronic-cigarette: effects on desire to smoke, withdrawal symptoms and cognition. Addict Behav 2012;37:970–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, et al. How do U.S. adults find out about electronic cigarettes? Implications for public health messages. Nicotine Tob Res Published Online First: 22 Apr 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borland R, Yong HH, Siahpush M, et al. Support for and reported compliance with smoke-free restaurants and bars by smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3) FDA E-Cigarettes: Impact on Individual and Population Health:iii34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult tobacco survey—19 states, 2003–2007. MMWR 2010;59:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gay M, Jackson J, Esterl M. New York City extends smoking ban to e-cigarettes. Wall Street J 2013 December 19. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303773704579268892537996818. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies A. Sorry smokers, you can't use electronic cigarettes on airplanes. 2013. http://www.businessinsider.com/you-cant-smoke-e-cigarettes-in-planes-2013-2.

- 46.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hodge JG, Jr, Collmer V, Orenstein DG, et al. Reconsidering the legality of cigarette smoking advertisements on television public health and the law. J Law Med Ethics 2013;41:369–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014;23:133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization. Electronic nicotine delivery systems, including electronic cigarettes. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jolly D. European parliament approves tough rules on electronic cigarettes. The New York Times 26 February 2014.

- 51.DiFranza JR, Richards JW, Paulman PM, et al. RJR Nabisco's cartoon camel promotes Camel cigarettes to children. JAMA 1991;266:3149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fischer PM, Schwartz MP, Richards JW, Jr, et al. Brand logo recognition by children aged 3 to 6 years. Mickey Mouse and Old Joe the Camel. JAMA 1991;266:3145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2012. MMWR 2014;63:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fishbein M. Great expectations, or do we ask too much from community-level interventions? Am J Public Health 1996;86:1075–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheeran P. Intention—behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2002;12:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopes M. E-cigarettes: a burning question for U.S. regulators. Reuters 2013. December 11.http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/12/11/us-usa-ecigarettes-idUSBRE9BA0ZT20131211 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith D, Bansal-Travers M, O'Connor RJ, et al. Perceptions about e-cigarette advertising and interest in product trial among US adults: results from a pilot study. Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; 5–8 February, Seattle, WA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.