Abstract

Endothelial cells forming the blood-brain barrier limit drug access into the brain, due to tight junctions, membrane drug transporters, and unique lipid composition. Passive permeability, thought to mediate drug access, is typically tested using porcine whole brain lipid. However human endothelial cell lipid composition differs. This investigation evaluated the influence of lipid composition on passive permeability across artificial membranes. Permeability of CNS-active drugs across an immobilized lipid membrane was determined using three lipid models: crude extract from whole pig brain, human brain microvessel lipid, and microvessel lipid plus cholesterol. Lipids were immobilized on polyvinylidene difluoride, forming donor and receiver chambers, in which drug concentration were measured after 2 hr. The log of effective permeability was then calculated using the measured concentrations. Permeability of small, neutral compounds was unaffected by lipid composition. Several structurally diverse drugs were highly permeable in porcine whole brain lipid but 1–2 orders of magnitude less permeable across human brain endothelial cell lipid. Inclusion of cholesterol had the greatest influence on bulky amphipathic compounds such as glucuronide conjugates. Lipid composition markedly influences passive permeability. This was most apparent for charged or bulky compounds. These results demonstrate the importance of using species-specific lipid models in passive permeability assays.

Keywords: PAMPA, lipid composition, passive permeability, blood brain barrier, central nervous system

Introduction

One major challenge hampering the success of neurotherapeutics is the difficulty in delivering drugs and diagnostic agents to the brain.1 This is due, in part, to the complexity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the site of molecular exchange between the blood and the brain. The BBB is formed by endothelial cells that line cerebral microvessels, and consists of both physical and metabolic barriers that work in tandem to maintain tight control of the brain microenvironment. The physical barrier consists of restrictive intercellular tight junctions between endothelial cells, greatly reduced vesicular transport, and a unique suite of proteins that transport nutrients, proteins, hormones, and drugs from the blood to the brain, as well as proteins that mediate the clearance of metabolic waste products and drugs in the opposite direction from the brain to the blood. The metabolic barrier, consisting of phase I and phase II drug metabolizing enzymes, functions to prevent lipophilic compounds from crossing the BBB by increasing their hydrophilicity.2–4 In order for a drug-like molecule to enter into the brain, it must pass through the plasma membrane of endothelial cells, transcellularly rather than paracellularly. Thus, vascular capillary endothelial cells are the “gatekeepers” of the brain, restricting the entry of toxic as well as potentially therapeutic compounds.

Many potential drugs have failed to succeed therapeutically, however, because they are either too bulky or lack the necessary lipophilicity, to cross the BBB, and thus unable to reach their therapeutic target. Therefore, it is important to understand endothelial cell membrane permeability potential when developing drugs for central nervous system (CNS) diseases. Several in vitro and computational models have been used as putatively physiologically relevant models in the drug discovery process to predict the BBB penetration potential of drug candidates. Computational models of drug permeability are typically based on molecular descriptors and range in complexity from simple multiple linear regression to machine-learning methods, and have varying degrees of prediction performance.5–7 Similarly, in vitro BBB models have a range of complexity, throughput and performance. The simplest models utilize lipid immobilized on a bead or solid support.8–10 In contrast, more complex, cell-based models use brain microvessel endothelial cells cultured either alone or co-cultured with astrocytes and/or pericytes.11

The parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) is an immobilized lipid model for measuring passive membrane permeability of small molecules. It was originally developed as a simple method for prediction of transcellular drug absorption and utilized a synthetic lipid immobilized on a filter support to mimic passive permeability across a cellular membrane.12 The assay has since been modified to mimic specific BBB,8 intestinal,13 and skin14 permeability barriers. The BBB-PAMPA assay as originally developed uses a lipid extract from whole pig brains (polar brain lipids).8 The assay was able to discriminate between BBB permeable or non-permeable compounds.8 However, when the assay was used in a separate study to predict in vivo brain penetration, the correlation between the effective permeability (Peff) for the porcine polar brain lipids model compared to the log BB (logarithm of the brain to plasma concentration ratio) after oral administration in rats of fourteen structurally diverse compounds was less than that determined using the synthetic lipid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine alone.15 This demonstrates the importance of using a model membrane that closely resembles the tissue or cells of interest, to ensure that the behavior seen with lipid model membrane reflects the behavior of cells in vitro and/or in vivo.16

The lipid composition of human BBB endothelial cell membranes (Table 1) differs from that of porcine polar whole brain lipid (PBL), traditionally used for PAMPA-BBB assays (Table 2). Such differences could potentially result in model misspecification when using pig brain lipid to predict human central nervous system drug disposition.

Table 1.

Lipid composition of human endothelial cell membranes

| Lipid | Human brain endothelial cell (%)29 | Human brain endothelial cell (%)31 | Human umbilical artery endothelial cell (%)30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylinositol | 5.5 | 4.8 | 6.0 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 22.8 | 25.2 | 28.1 |

| Phosphatidylinositol + phosphatidic acid | 4.8 | ||

| Phosphatidylcholine | 28.7 | 33.2 | 49.0 |

| Phosphatidylserine | 6.8 | 10.7 | 9.0 |

| Sphingomyelin | 33.4 | 17 | 5.9 |

| Cholesterol | 20.8 |

Table 2.

Lipid composition of PAMPA modelsa

| Porcine polar brain lipid (PBL) (%)* | Microvessel lipid (MVL) (%) | Microvessel lipid + cholesterol (MVLC) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylinositol | 6.0 | 4.8 | 5.5 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 28.1 | 25.2 | 22.8 |

| Phosphatidylinositol + phosphatidic acid | 4.8 | ||

| Phosphatidylcholine | 49.0 | 33.2 | 28.7 |

| Phosphatidylserine | 9.0 | 10.7 | 6.8 |

| Sphingomyelin | 5.9 | 17 | 33.4 |

| Cholesterol | 20.8 | ||

| Other | 30.9 |

Expressed as per cent of total mass

Avanti Polar Lipids (http://avantilipids.com)

The objective of the present study was to compare the effect of membrane lipid composition on the passive permeability of eighteen compounds and metabolites active in the central nervous system using the PAMPA assay. In addition to traditional porcine polar whole brain lipid, one model system was designed to reflect the lipid composition of human brain endothelial cells (microvessel lipid model, MVL), and the other model to reflect human brain endothelial cell lipid and cholesterol content (microvessel lipid plus cholesterol, MVLC). The hypothesis was that lipid and cholesterol composition in model lipid systems would influence passive permeability.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Multiscreen polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) 96-well plates and Transporter Receiver Plates were obtained from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA). Lipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) with the exception of sphingomyelin, cholesterol, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine which were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Verapamil, loperamide, theophylline, (±) methadone HCl, fentanyl citrate, codeine, diazepam, hydromorphone HCl, alprazolam, caffeine, atenolol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Alfentanil, norbuprenorphine, buprenorphine, buprenorphine-3-β-D-glucuronide, morphine-3-glucuronide, morphine-6-glucuronide and oxycodone were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Resources Drug Supply Program. Oxazepam was obtained from Hoffman-La Roche. Sufentanil and dihydromorphine were obtained from Cerillant (Round Rock, TX) and morphine sulfate from Mallinckrodt (St. Louis, MO). Tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Company (Santa Cruz, CA). Norbuprenorphine-3-β-D-glucuronide was synthesized from norbuprenorphine using dog liver microsomes.17 Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS), pH 7.4 was obtained from MediaTech (Manassas, VA).

Methods

With the exception of the polar brain lipid, which was solubilized as received from the manufacturer, the individual components for each lipid preparation were solubilized in anhydrous dodecane (Sigma). All lipid preparations had a total lipid concentration of 20 mg/mL and were prepared fresh prior to each assay. Each of the test compounds was diluted to 2mM in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma) and further diluted prior to testing to 2 μM in HBSS, pH 7.4. The assay was performed using a 96-well Multiscreen-IP PAMPA plate (Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA). Each well was prepared by first adding 4 μL of the lipid suspension to the PVDF membrane of the filter plate, as described previously.8 Immediately following the addition of the lipid to the membrane, the donor (upper) chamber was filled with HBSS solution containing the compound to be tested (200 μL). HBSS was also added to the receiver plate (300 μL) and the filter and receiver plates were then assembled and incubated for 2 hr at room temperature in a moistened sealed bag to prevent evaporation. At the end of the incubation period, 100 μL was removed from the receiver plate, and the concentration was determined by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry. An additional equilibrium plate was used, that represents a theoretical, partition-free sample. The equilibrium plate was prepared by adding 300 μL of HBSS and 200 μL of HBSS plus 2 μM drug to a 96-well deep well plate, mixing and transferring 100 μL of the diluted drug to a new plate for analysis. Analysis of each compound was performed in triplicate on three different days.

Analytes were quantified by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry. Samples were diluted 1:1 with purified water (MilliQ, Millipore) containing 0.1μg/mL norfentanyl d5 (Cerilliant) as the internal standard and mixed thoroughly. LC/MS/MS analysis was performed on an ultra-fast liquid chromatography system from Shimadzu Scientific Instruments (Columbia, MD) consisting of a CMB-20A system controller, two LC-20ADXR pumps, a DGU-20A3 degasser, a SIL-20AC autosampler, and a CTO-20A column oven. An external switching valve was installed between the chromatography system and the mass spectrometer. The chromatography system was coupled to an API 4000 QTrap LC/MS/MS linear ion trap triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer from Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex (Foster City, CA). The mass spectrometer was equipped with a Turbo Ion Spray ionization source operating in positive ionization mode. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Sunfire C18 HPLC column (50 × 2.1mm, 3.5 μm) (Waters Corp, Milford, MA). The injection volume was 10 μL, the autosampler temperature was 15°C, and the oven temperature was 40°C. The HPLC mobile phase (0.3 mL/min) was (A) 4.5 mM ammonium acetate in water, pH 4.5 and (B) 4.5mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile. The gradient program was as follows: 0 to 0.5 min 5% B, increased linearly to 95% B at 1 min, held at 95% B until 2.5 min, linearly decreased to 5% B over 0.01 min and re-equilibrated at 5% B until 4 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive-ion mode with an ion spray voltage of 5500 V. The source temperature was 450°C, entrance potential was 10V for all compounds, and curtain gas, ion source gas 1, ion source gas 2, and collision gas (all ultrahigh purity nitrogen) were 20 psig, 30 psig, 40 psig, and medium setting, respectively. Both Q1 and Q3 quadrupoles were optimized to unit mass resolution, and the mass spectrometer conditions were optimized for each analyte. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for each analyte and internal standard, as well as other mass spectrometric parameters, are provided in the Supplemental Table. Standard curves were prepared by spiking blank media with pure compound over a concentration range of 1–1000ng/mL. Quantitation was performed by using area ratios of parent to internal standard with all calibrations and calculations performed in Analyst software version 1.5.2.

Canonical SMILES strings for each compound were obtained from the PubChem web site (pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and molecular descriptors (Table 3) were calculated using ACD/I-Lab (Advanced Chemistry Development Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada).

Table 3.

Structural features and molecular descriptorsa

| Drug | LogP | pKa | PSAb (Å2) | Fraction unionized or ionized at pH 7.4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Substituents | +1 charge (%) | 0 charge (%) | −1 charge (%) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

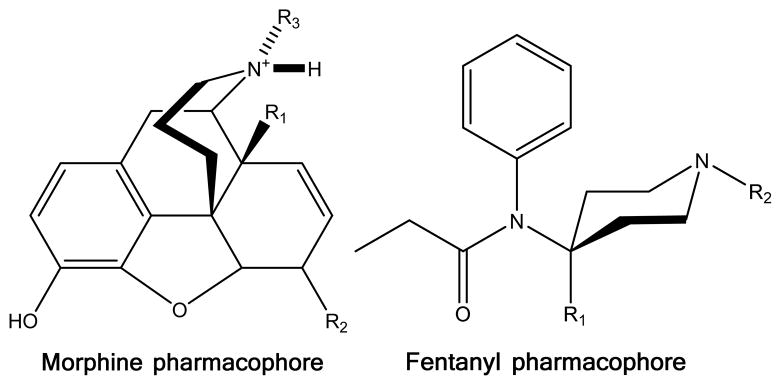

| Morphine-like | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | C7-C8 double bond | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Morphine | -H | -OH | -CH3 | -H | Yes | 0.87 | 8.2 | 52.93 | 85 | 13 | 0.1 |

| Codeine | -CH3 | -OH | -CH3 | -H | Yes | 1.09 | 8.2 | 41.93 | 87 | 14 | |

| Oxycodone | -CH3 | =O | -CH3 | -OH | No | 0.50 | 8.1 | 59.00 | 82 | 18 | |

| Hydromorphone | -H | =O | -CH3 | -H | No | 1.25 | 8 | 49.77 | 81 | 18 | 0.1 |

| Dihydromorphine | -OH | -OH | -CH3 | -H | No | 1.48 | 8.2 | 52.93 | 85 | 13 | 1 |

| Morphine 3-Glucuronide | -OH | -CH3 | -H | Yes | −2.07 | 8.2 | 149.15 | 14 | |||

| Morphine 6-Glucuonide | -OH | -CH3 | -H | Yes | −1.32 | 8.1 | 149.15 | 16 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

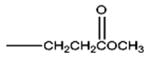

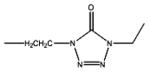

| Fentanyl-like | R1 | R2 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Fentanyl | -OH |

|

4.2 | 23.55 | 83 | 17 | |||||

| Sufentanil | -OCH3 |

|

4.15 | 8.2 | 61.02 | 86 | 14 | ||||

| Remifentanil | -OCH3 |

|

1.98 | 6.7 | 76.15 | 17 | 83 | ||||

| Alfentanil | -OCH3 |

|

2.47 | 6.5 | 81.05 | 12 | 88 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Buprenorphine | 4.81 | 0.86 | 62.16 | 88 | 11 | ||||||

| Buprenorphine Glucuronide | 2.23 | 2.9 | 158.38 | 90.8 | |||||||

| Norbuprenorphine | 3.56 | 8.7 | 70.95 | 95 | 4 | 0.9 | |||||

| Atenolol | 0.09 | 13.8 | 84.58 | 99.2 | 0.8 | ||||||

| Verapamil | 4.22 | 63.95 | 95.5 | 4.6 | |||||||

| Loperamide | 5.65 | 13.7 | 43.78 | 90.9 | 9.1 | ||||||

| Methadone | 4.23 | 20.31 | 95.2 | 4.8 | |||||||

| Tramadol | 2.65 | 14.2 | 32.70 | 98.6 | 1.4 | ||||||

| O-desmethyl tramadol | 2.14 | 10.3 | 43.70 | 97.8 | 0.3 | 1.9 | |||||

| Alprazolam | 2.45 | 42.55 | 2 | 98 | |||||||

| Oxazepam | 2.04 | 11.5 | 61.69 | 99.99 | |||||||

| Diazepam | 2.87 | 32.67 | 0.01 | 99.99 | |||||||

| Theophylline | 0.02 | 8.74 | 69.30 | 95.2 | |||||||

| Caffeine | 0.11 | 58.44 | |||||||||

Calculations

The log of the effective permeability was calculated using equation 1:18

| (equation 1) |

Each data point represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate determinations performed on the same day.

Results and Discussion

The polar brain lipid-based PAMPA assay was developed to measure the passive permeability of compounds in a brain lipid environment.8 However, the lipid typically used for this assay is from pig brain, rather than human brain, and more specifically, is extracted from the whole pig brain, rather than from brain microvessel endothelial cells. These considerations confer substantial differences in the abundance of several component phospholipids in the brain (Table 1). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of using a more physiologically-relevant phospholipid composition (human, and microvessel endothelial lipid) on the effective permeability of CNS active drugs. Representative compounds from several drug classes were selected, including morphine- and fentanyl-like opioids, other opioids, benzodiazepines, and drugs commonly used to benchmark brain permeability.

Control experiments were performed to determine if permeability was due to interactions with the phospholipids/sphingomyelin/cholesterol or with the nonpolar solvent dodecane. Thus, the PAMPA assay was performed using the lipid solvent dodecane alone, without lipid, between the donor and receiver chambers (Table 4). Comparison of results to permeability with the lipid models reflects the role of the lipid membrane per se. With dodecane alone, morphine, oxycodone, dihydromorphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, and the glucuronide conjugates of both morphine and buprenorphine were unable to cross the barrier, indicating the obligate necessity of lipid interaction for membrane permeability. The effective permeability in the dodecane-only model for hydromorphone, norbuprenorphine, tramadol, alprazolam, oxazepam, and diazepam was generally greater in the three lipid-containing models than with dodecane alone. For the remaining compounds, alfentanil, sufentanil, and O-desmethyl tramadol, the logPe values were equivalent in the presence or absence of lipid. The differences between these three groups of compounds are likely due to two separate properties. Compounds that were unable to cross the dodecane barrier, such as the glucuronide conjugates of buprenorphine and morphine, are likely too charged. These compounds have 5 H-donor and 10 (or 11) H-acceptor sites. In contrast, for compounds such as fentanyl and buprenorphine, which are highly lipophilic (as measured by their logP values), the rate-limiting step may be rapid uptake into the lipid membrane, but slow desorption off the membrane surface into the receiving buffer.

Table 4.

Permeability results

| Drug | Permeability (Log Pe, cm/sec)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine polar brain lipid (PBL) | Microvessel lipid (MVL) | Microvessel lipid + cholesterol (MVLC) | Dodecane | |

| Morphine | −1.49 ± 0.07 | −2.76 ± 0.21 | −2.86 ± 0.26 | ND |

| Oxycodone | −0.83 ± 0.17 | −2.54 ± 0.2 | −2.40 ± 0.17 | ND |

| Hydromorphone | −0.24 ± 0.02 | −2.37 ± 0.29 | −2.57 ± 0.04 | −3.82 ± 0.06 |

| Dihydromorphine | −1.76 ± 0.09 | −2.82 ± 0.32 | ND | ND |

| Morphine-3-glucuronide | ND | ND | −3.03 ± 0.11 | ND |

| Morphine 6-glucuonide | ND | ND | −3.54 ± 0.22 | ND |

| Fentanyl | −2.13 ± 0.11 | −2.48 ± 0.2 | −3.60 ± 0.2 | ND |

| Sufentanil | −3.15 ± 1.06 | −2.69 ± 0.29 | −2.78 ± 0.16 | −3.57 ± 0.06 |

| Remifentanil | −0.33 ± 0.03 | −2.49 ± 0.68 | −2.40 ± 0.19 | −3.76 ± 0.16 |

| Alfentanil | −0.06 ± 0.01 | −2.11 ± 0.25 | −2.88 ± 0.23 | −1.75 ± 0.45 |

| Buprenorphine | −3.92 ± 0.43 | −1.59 ± 0.13 | −3.03 ± 0.28 | ND |

| Buprenorphine glucuronide | ND | ND | −3.27 ± 0.21 | ND |

| Norbuprenorphine | −4.52 ± 0.17 | −2.31 ± 0.35 | −1.91 ± 0.1 | −4.15 ± 0.02 |

| Atenolol | −6.44 ± 0.7 | −3.49 ± 0.07 | −3.51 ± 0.09 | |

| Verapamil | −2.88 ± 0.16 | −2.67 ± 0.05 | −2.38 ± 0.05 | −3.99 ± 0.06 |

| Loperamide | −2.29 ± 0.33 | −2.94 ± 0.53 | −1.97 ± 0.08 | −3.69 ± 0.03 |

| Methadone | −0.37 ± 0.07 | −2.50 ± 0.26 | ND | −1.54 ± 0.05 |

| Tramadol | −2.34 ± 0.04 | ND | −2.67 ± 0.02 | −3.93 ± 0.02 |

| O-desmethyl tramadol | −0.97 ± 0.04 | −2.19 ± 0.32 | −2.25 ± 0.32 | −2.09 ± 0.02 |

| Alprazolam | −0.12 ± 0.06 | −1.18 ± 0.12 | −1.12 ± 0.14 | −2.68 ± 0.15 |

| Oxazepam | −0.65 ± 0.21 | −0.78 ± 0.18 | −1.03 ± 0.05 | −3.42 ± 0.15 |

| Diazepam | −1.08 ± 0.23 | −0.65 ± 0.06 | −0.78 ± 0.18 | −1.31 ± 0.02 |

| Theophylline | ND | ND | ND | −3.99 ± 0.03 |

| Caffeine | −2.48 ± 0.19 | −3.14 ± 0.2 | ND | ND |

ND – Not detectable in the receiver compartment

Subsequent evaluations compared the influence of membrane lipid composition in permeability of the representative compounds (Table 4). Oxazepam, diazepam and alprazolam were highly permeability in all three lipid models. All three compounds are uncharged (>98%) at pH 7.4, and, they may cross the membrane without the need for hydrogen bonding with the lipids. Another possibility is that these compounds cross the artificial membrane through paramembrane water channels that are thought to exist.19 However, the lipid compositions in the three MVL and MVLC models did influence the movement of these benzodiazepines across the lipid membrane, with differences between the human and porcine lipids, and between the human lipid with and without cholesterol. This may be affected by tighter packing of the phospholipid/sphingomyelin molecules in the MVL and MVLC models. In contrast, compounds such as alfentanil, remifentanil, hydromorphone, and norbuprenorphine were highly permeable in the PBL model, but one to two orders of magnitude less permeable in either the MVLC or MVL models, and, in addition, the absence or presence of cholesterol in the MVL model had little influence on their permeability. These results are not readily be explained by molecular charge, polar surface area, or logP.

For most compounds, the PBL model appears to be less restrictive than either of the models using species-relevant lipid compositions. The only exceptions were sufentanil, diazepam, and the glucuronide conjugates, which had greater permeability in both the human MVLC and MVL models than the PBL model. One possible explanation for the generally greater permeability of the porcine polar brain lipid monolayer, compared with human brain lipid, may be the lower content of sphingomyelin. Since, however, the lipid content of the PBL model is not fully characterized, with approximately 30% of the lipid undefined, additional explanations may exist.

For the two cholesterol-free models, porcine PBL and human MVL, the greatest difference in permeability between models appears to be for those compounds (i.e., remifentanil, alfentanil) that have extensive hydrogen bond acceptor potential but are primarily (>80%) uncharged at pH 7.4. In contrast, opioids that are structurally similar to remifentanil and alfentanil (i.e., fentanyl and sufentanil) but have a limited capacity to form hydrogen bonds and are charged at pH 7.4, have log Pe values which are much more similar in the porcine and human lipid models. These differences may be reflective of lower sphingomyelin content in the PBL compared to MVL models. Sphingomyelins, because of their amide bond at position 2 and hydroxyl at position 3 of the sphingoid base, are capable of acting as both a hydrogen donor and acceptor. In contrast, phosphatidylcholine can act only as a hydrogen acceptor due to the two ester carbonyl groups.20

The presence of cholesterol in the artificial human membrane appears to have the greatest influence on bulky amphipathic compounds such as the glucuronide conjugates of buprenorphine and morphine. These compounds have extensive hydrogen bonding potential and primarily exist as a zwitterion (±1) at pH 7.4. However, the presence of cholesterol also influenced the permeability of highly lipophilic compounds such as fentanyl. Cholesterol has been shown to interact with sphingomylin forming ‘rafts’ which influence phospholipid packing, membrane fluidity and the pharmacological effect of some drugs.21–24 The lower permeability of fentanyl in the cholesterol- containing MVL model is surprising and may represent a high level of lipid retention.

The unique barrier properties of brain microvessel endothelial cells function to maintain a defined environment for the central nervous system by allowing specific nutrients to enter, eliminating waste products, and excluding substances potentially toxic to neuronal tissue. Among those substances with variable entre are drugs for treating neurological disorders and pain. The relative roles of carrier-mediated uptake and passive diffusion in brain access and bioavailability of drugs remains under active discussion.25–27 The standard model for assessing passive permeability is the PAMPA assay. PAMPA studies designed to model the blood-brain permeability of therapeutic drugs and metabolites, and to predict the permeability of compounds in development, are increasingly evaluating larger families of compounds, yet continue to use porcine whole brain polar lipid.15,19,28 Nevertheless, two considerations prevail, specifically, the relevance of whole brain lipid and species differences.

The lipid composition of brain microvessel endothelial cells, which are the primary determinant of the blood-brain barrier, is unique, such that the amount of sphingomyelin is approximately 3-fold higher, and phosphatidylcholine content is decreased by approximately one-third, compared with other endothelial cells.29,30 The relative abundance of these two structurally similar, but functionally dissimilar phospholipids, has the potential to alter phospholipid packing within the membranes and phospholipid-cholesterol interactions. These in turn can influence the ability of compounds to interact with the lipids of the BBB, as well as their ability to form hydrogen bonds, thereby affecting the permeability of (potential) therapeutic compounds.

The lipid composition of porcine whole brain extracts differs from human brain endothelial cell lipid. The permeability of drugs in rodent in situ brain perfusion studies correlates well with PAMPA studies based on porcine brain lipid extract.15,19,28 However the ability of porcine whole brain PAMPA assays to predict human brain drug access in vivo remains unknown.

These considerations are validated by the results and conclusions of the present investigation, which demonstrate that in a small series of drugs, there are significant differences in the passive permeability of various compounds, between porcine and human lipid, and between the porcine whole-brain lipid model and those reflecting human endothelial cell lipid composition. This highlights the need to reevaluate the current BBB-PAMPA assay using porcine polar brain lipid, in order to better model human brain biodistribution, in order to identify compounds having the greatest likelihood of reach their brain targets.

Supplementary Material

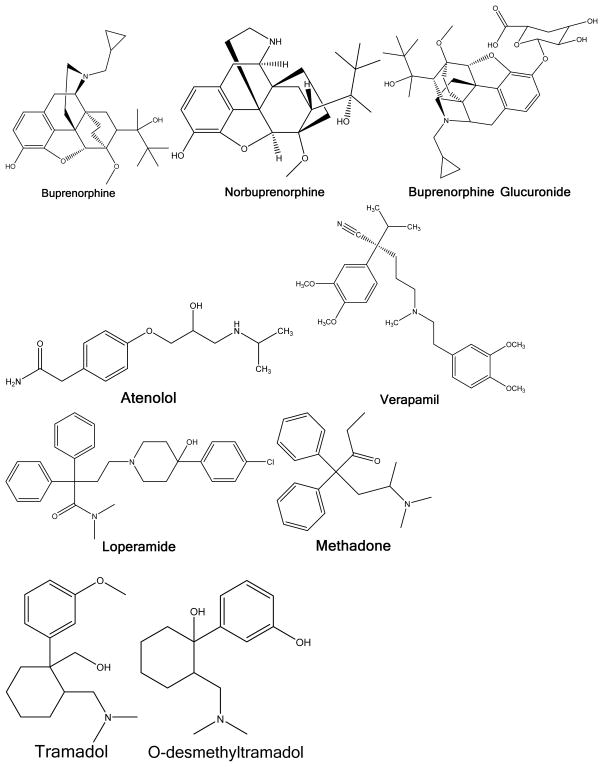

Figure 1.

Morphine and fentanyl pharmacophores. Specific compounds and substituents are described in table 3.

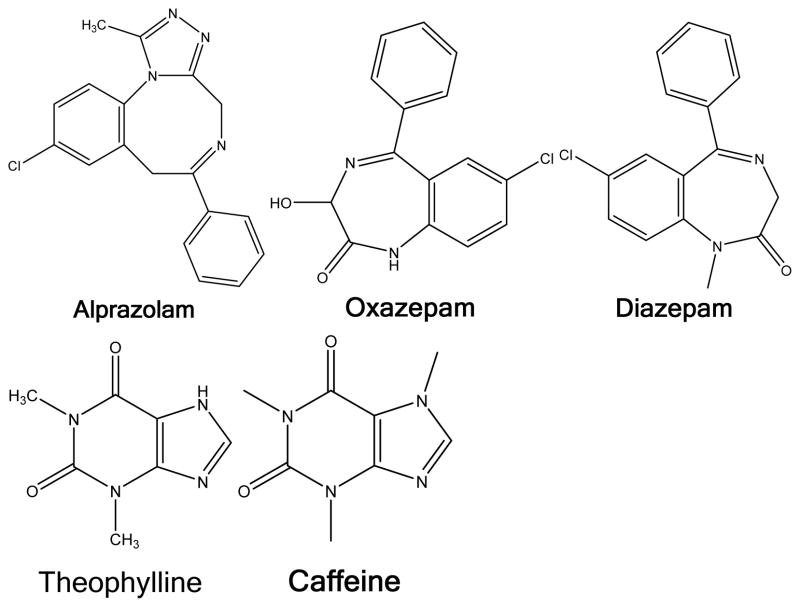

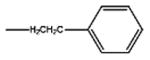

Figure 2.

Structures of individual compounds

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institutes of Health grants R01-GM63674, R01-DA14211, R01-DA025931 and K24-DA00417 (to EDK)

Footnotes

- Title: Research Instructor

- Affiliation: Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO

- campbels@anest.wustl.edu

- Contribution: study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation

- Conflicts of Interest: none

- Title: Research Lab Manager

- Affiliation: Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO

- reginak@wustl.edu

- Contribution: study design, conduct of the study, data collection, manuscript preparation

- Conflicts of Interest: none

- Title: Vice Chancellor for Research, Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Professor of Anesthesiology, Director, Division of Clinical and Translational Research, Department of Anesthesiology, Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics

- Affiliation: Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

- kharasch@wustl.edu

- Contribution: study design, manuscript preparation

- Attestation: reviewed the original study data and data analysis, attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript, approved the final manuscript

- Conflicts of Interest: none

References

- 1.Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier drug targeting: the future of brain drug development. Mol Interv. 2003;3:90–105. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minn A, Ghersi-Egea JF, Perrin R, Leininger B, Siest G. Drug metabolizing enzymes in the brain and cerebral microvessels. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1991;16:65–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghersi-Egea JF, Leininger-Muller B, Suleman G, Siest G, Minn A. Localization of drug-metabolizing enzyme activities to blood-brain interfaces and circumventricular organs. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1089–1096. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutheil F, Dauchy S, Diry M, Sazdovitch V, Cloarec O, Mellottee L, Bieche I, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Flinois JP, de Waziers I, Beaune P, Decleves X, Duyckaerts C, Loriot MA. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in the normal human brain: regional and cellular mapping as a basis for putative roles in cerebral function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1528–1538. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou T, Wang J, Zhang W, Wang W, Xu X. Recent advances in computational prediction of drug absorption and permeability in drug discovery. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:2653–2667. doi: 10.2174/092986706778201558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dauchy S, Miller F, Couraud PO, Weaver RJ, Weksler B, Romero IA, Scherrmann JM, De Waziers I, Decleves X. Expression and transcriptional regulation of ABC transporters and cytochromes P450 in hCMEC/D3 human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh C, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Hossain M, Cucullo L, Fazio V, Janigro D, Marchi N. Pattern of P450 expression at the human blood-brain barrier: roles of epileptic condition and laminar flow. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1408–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di L, Kerns EH, Fan K, McConnell OJ, Carter GT. High throughput artificial membrane permeability assay for blood-brain barrier. Eur J Med Chem. 2003;38:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichel A, Begley DJ. Potential of immobilized artificial membranes for predicting drug penetration across the blood-brain barrier. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1270–1274. doi: 10.1023/a:1011904311149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loidl-Stahlhofen A, Hartmann T, Schottner M, Rohring C, Brodowsky H, Schmitt J, Keldenich J. Multilamellar liposomes and solid-supported lipid membranes (TRANSIL): screening of lipid-water partitioning toward a high-throughput scale. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1782–1788. doi: 10.1023/a:1013343117979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deli MA, Abraham CS, Kataoka Y, Niwa M. Permeability studies on in vitro blood-brain barrier models: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:59–127. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kansy M, Senner F, Gubernator K. Physicochemical high throughput screening: parallel artificial membrane permeation assay in the description of passive absorption processes. J Med Chem. 1998;41:1007–1010. doi: 10.1021/jm970530e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugano K, Nabuchi Y, Machida M, Aso Y. Prediction of human intestinal permeability using artificial membrane permeability. Int J Pharm. 2003;257:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinkó B, Garrigues TM, Balogh GT, Nagy ZK, Tsinman O, Avdeef A, Takacs-Novak K. Skin-PAMPA: a new method for fast prediction of skin penetration. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;45:698–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mensch J, Melis A, Mackie C, Verreck G, Brewster ME, Augustijns P. Evaluation of various PAMPA models to identify the most discriminating method for the prediction of BBB permeability. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2010;74:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peetla C, Stine A, Labhasetwar V. Biophysical interactions with model lipid membranes: applications in drug discovery and drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1264–1276. doi: 10.1021/mp9000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan J, Brown SM, Tu Z, Kharasch ED. Chemical and enzyme-assisted syntheses of norbuprenorphine-3-β-D-glucuronide. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:752–758. doi: 10.1021/bc100550u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wohnsland F, Faller B. High-throughput permeability pH profile and high-throughput alkane/water log P with artificial membranes. J Med Chem. 2001;44:923–930. doi: 10.1021/jm001020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsinman O, Tsinman K, Sun N, Avdeef A. Physicochemical selectivity of the BBB microenvironment governing passive diffusion--matching with a porcine brain lipid extract artificial membrane permeability model. Pharm Res. 2011;28:337–363. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hertz R, Barenholz Y. Permeability and integrity properties of lecithin-sphingomyelin liposomes. Chem Phys Lipids. 1975;15:138–156. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(75)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohvo-Rekila H, Ramstedt B, Leppimaki P, Slotte JP. Cholesterol interactions with phospholipids in membranes. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41:66–97. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomae AV, Koch T, Panse C, Wunderli-Allenspach H, Kramer SD. Comparing the lipid membrane affinity and permeation of drug-like acids: the intriguing effects of cholesterol and charged lipids. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1457–1472. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9263-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Meyer F, Smit B. Effect of cholesterol on the structure of a phospholipid bilayer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3654–3658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809959106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons K, Sampaio JL. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004697. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobson PD, Kell DB. Carrier-mediated cellular uptake of pharmaceutical drugs: an exception or the rule? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:205–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugano K, Kansy M, Artursson P, Avdeef A, Bendels S, Di L, Ecker GF, Faller B, Fischer H, Gerebtzoff G, Lennernaes H, Senner F. Coexistence of passive and carrier-mediated processes in drug transport. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:597–614. doi: 10.1038/nrd3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di L, Artursson P, Avdeef A, Ecker GF, Faller B, Fischer H, Houston JB, Kansy M, Kerns EH, Kramer SD, Lennernas H, Sugano K. Evidence-based approach to assess passive diffusion and carrier-mediated drug transport. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mensch J, Jaroskova L, Sanderson W, Melis A, Mackie C, Verreck G, Brewster ME, Augustijns P. Application of PAMPA-models to predict BBB permeability including efflux ratio, plasma protein binding and physicochemical parameters. Int J Pharm. 2010;395:182–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siakotos AN, Rouser G. Isolation of highly purified human and bovine brain endothelial cells and nuclei and their phospholipid composition. Lipids. 1969;4:234–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02532638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takamura H, Kasai H, Arita H, Kito M. Phospholipid molecular species in human umbilical artery and vein endothelial cells. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:709–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tewes BJ, Galla HJ. Lipid polarity in brain capillary endothelial cells. Endothelium. 2001;8:207–220. doi: 10.1080/10623320109051566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.