Abstract

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended as postoperative analgesia by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. Recent studies have raised concerns that NSAID administration following colorectal anastomosis may be associated with increased risk of anastomotic leak. This multicentre study aims to determine NSAIDs’ safety profile following gastrointestinal resection.

Methods and analysis

This prospective, multicentre cohort study will be performed over a 2-week period utilising a collaborative methodology. Consecutive adults undergoing open or laparoscopic, elective or emergency gastrointestinal resection will be included. The primary end point will be the 30-day morbidity, assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification. This study will be disseminated through medical student networks, with an anticipated recruitment of at least 900 patients. The study will be powered to detect a 10% increase in complication rates with NSAID use.

Ethics and dissemination

Following the Research Ethics Committee Chairperson's review, a formal waiver was received. This study will be registered as a clinical audit or service evaluation at each participating hospital. Dissemination will take place through previously described novel research collaborative networks.

Keywords: Surgery

Background

The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society recommends the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as part of postoperative analgesia protocols.1 The routine use of NSAIDs is also endorsed by the WHO's Pain Relief Ladder. NSAIDs have been shown to be generally effective and safe as postoperative analgesia, with an opioid-sparing effect.2 3

Recent evidence has questioned the safety of NSAIDs following major gastrointestinal (GI) surgery. Two retrospective analyses of different prospective databases of patients undergoing primary colorectal anastomosis found that specific NSAIDs may increase the risk of anastomotic leak. The first showed that among 2800 patients postoperative diclofenac use was independently associated with increased risk.4 The second studied 500 patients, finding that the introduction of protocolised use of celecoxib brought a significant increase in the anastomotic leak rate from around 3% to 15%.5 A further retrospective study of 800 patients also suggested that non-selective NSAIDs may increase anastomotic leak rates.6

These clinical findings are supported by animal studies that have demonstrated that NSAID use following bowel anastomosis may be associated with decreased anastomotic strength and increased leak rates.7 8 NSAIDs are implicated in reducing collagen synthesis and hydroxyproline deposition during the healing process. Downregulation of prostaglandin expression may also increase microthrombus and microembolus formation, further contributing to postoperative adverse effects.

The need for further evidence

Concerns have been raised about the safety of NSAIDs following bowel anastomosis; however, the majority of the evidence until now is reliant on secondary analyses or retrospective series. Most studies concern colorectal surgery, with very little evidence available for oesophageal and gastric surgery. Furthermore, most studies focus on anastomotic leaks, providing no evidence on the broader side effect profiles of NSAIDs, which may include increased risk of GI bleeding, cardiac ischaemia and renal failure.

Primary aim

The primary aim of this study was to determine the safety profile of postoperative NSAIDs after GI resection in current practice across the UK.

Hypothesis

The 30-day adverse event rate, following risk adjustment, should be equivalent in patients taking and not taking NSAIDs.

Methods

Study design

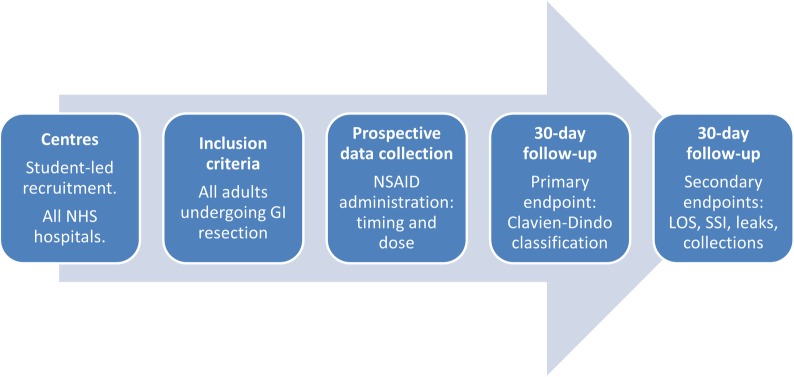

We plan to undertake a national multicentre prospective audit which will be disseminated through university medical school and student networks (figure 1). The generic collaborative methodology has been described previously.9

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study design. GI, gastrointestinal; LOS, length of stay; SSI, surgical site infection.

Study setting

This study will take place in general surgical units in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals. Any of the NHS hospitals performing elective or emergency GI resection may participate. Each centre will contribute 2 weeks of consecutive patient data from up to two study periods.

Inclusion criteria

Consecutive adult patients undergoing upper or lower GI bowel resection.

Patients undergoing either elective or emergency, and open, laparoscopic, laparoscopic-assisted or laparoscopic-converted procedures may be included.

Bowel resection is defined as complete transection and removal of a segment of the rectum, colon, small bowel, stomach or oesophagus.

Exclusion criteria

Patients under 18 years of age.

Appendicectomy for acute appendicitis. Patients who undergo incidental appendicectomy as part of another procedure may be included.

Any procedure with bowel repair, but without resection.

Wedge resection without complete bowel transaction.

Trauma indication.

Gynaecological primary indication.

Urological primary indication.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure will be the 30-day adverse event rate, measured by the Clavien-Dindo classification. This is an internationally standardised and validated scoring system for postoperative complications (table 1).10

Table 1.

The Clavien-Dindo classification of postoperative complications

| Grade | Definition (examples listed in italics) |

|---|---|

| I | Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment other than the “allowed therapeutic regimens”, or surgical, endoscopic and radiological interventions Allowed therapeutic regimens are: drugs as antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics and electrolytes. This grade also includes physiotherapy and wound infections opened at the bedside but not treated with antibiotics Examples: Ileus, thrombophlebitis |

| II | Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs beyond those allowed for grade I complications. Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition are also included Examples: Surgical site infection treated with antibiotics, myocardial infarction treated medically, deep venous thrombosis treated with low-molecular weight heparin, pneumonia or urinary tract infection treated with antibiotics |

| III | Requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention Examples: return to theatre for any reason, endoscopic therapy, interventional radiology |

| IV | Life-threatening complication requiring critical care management; CNS complications including brain haemorrhage and ischaemic stroke (excluding TIA), subarachnoidal bleeding Examples: Single or multiorgan dysfunction requiring critical care management, for example, pneumonia with ventilator support, renal failure with filtration |

| V | Death of a patient |

CNS, central nervous system; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures will be anastomotic leak, wound infection and cardiovascular events (table 2).

Table 2.

Secondary outcome measures

| Outcome measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Length of stay | Day of admission counts as day 1, and the day of discharge as a whole day |

| Anastomotic leak | Anastomotic leak detected clinically/symptomatically, radiologically and/or intraoperatively |

| Intra-abdominal/intrapelvic collection | Abscess/collection leak detected clinically/symptomatically, radiologically and/or intraoperatively |

| Wound infection | Based on the Centre for Disease Control's definition of surgical site infection,11 which is any one of: (1) Purulent drainage from the incision (2) At least two of: pain or tenderness; localised swelling; redness; heat; fever; AND the incision is opened deliberately to manage infection or the clinician diagnoses a surgical site infection (3) Wound organisms AND pus cells from the aspirate/swab |

| Cardiac event | Includes myocardial infarction, unstable angina, sudden death from cardiac causes, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, peripheral arterial thrombosis, peripheral venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus |

Explanatory variables

Administration of NSAIDs from day 1 (day of surgery) through to the third postoperative day is the main explanatory variable. Patients will be stratified into high (recommended daily dose or above) or low (below the recommended daily dose, including once only) NSAID dose groups. Data will be collected on the specific NSAID administered in order to allow analysis by NSAID type. Aspirin will not be considered as an NSAID for this analysis, although data on its administration will be collected. The Revised Cardiac Risk Index will be calculated for each patient to adjust for pre-existing cardiovascular risk (box 1).12 Data will be collected on the operation type (colorectal or upper GI/hepatobiliary) to facilitate analysis of homogeneous operative groups.

Box 1. The Revised Cardiac Risk Index.

Revised Cardiac Risk Index

History of ischaemic heart disease

History of congestive heart failure

History of cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischaemic attack)

History of diabetes requiring preoperative insulin use

Chronic kidney disease (creatinine >177 mmol/L)

Undergoing suprainguinal vascular, intraperitoneal or intrathoracic surgery

Quality assurance

Although many collaborators participating in the study will be medical students, each local team must include at least one qualified doctor to closely supervise the students. The study will additionally be registered with a sponsoring consultant surgeon at each site.

A detailed protocol describing how to register the study and an in-depth description of data fields and how to collect them will be made available to collaborators. This protocol will be interactively presented and explained in detail at a national collaborators meeting. Regional leads for the study will also be encouraged to hold meetings with local collaborating teams to debrief them on the protocol. Feedback from these meetings will be used to clarify any ambiguities in the protocol.

To ensure that collaborators understand the inclusion criteria and application of the Clavien-Dindo classification, they will be asked to complete a case-based online e-learning module prior to starting data collection.

In order to overcome a learning curve in identifying patients and relevant data, all participating centres will be asked to pilot completing patient identification and the initial stages of the data collection form for 1 day in the week leading up to the main study starting date.

Throughout the data collection period, the trial management group will hold weekly Twitter question and answer sessions (http://www.twitter.com/STARSurgUK), giving an opportunity for collaborators to clarify any uncertainties regarding the protocol. A summary of frequently asked questions will be distributed to all collaborators following each Twitter session, providing real-time feedback to collaborators.

Validation

Following data collection, only data sets with >95% data completeness will be accepted for pooled national analysis. An independent assessor will validate 5% of all data points, with a target of >98% accuracy.

Data management

A standardised Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Excel 2010; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) with preset fields will be used to collect data at each centre. Data protection regulations at each centre will be complied with. Patient identifiable data will not be transmitted to the trial management group. The required anonymous data fields are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Required data fields

| 1 | Patient age (whole years) | Years |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Patient gender | Male, female |

| 3 | ASA score | I, II, III, IV, V |

| 4 | History of ischaemic heart disease | Yes, no |

| 5 | History of congestive heart failure | Yes, no |

| 6 | History of cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischaemic attack) | Yes, no |

| 7 | History of diabetes | No, diet, controlled, tablet controlled, insulin controlled |

| 8 | Chronic kidney disease (creatinine >177 μmol/L) | Yes, no |

| 9 | Was the patient taking regular aspirin? | Yes, and restarted in the first 7 postoperative days; yes, but did not restart in the first 7 postoperative days; no |

| 10 | Was the patient taking a perioperative statin? | Yes, high dose (40 mg OD simvastatin or equivalent), Yes, low dose (5–20 mg OD simvastatin or equivalent), No |

| 11 | Date of operation | DD/MM/YY |

| 12 | Time of operation | 24 h clock |

| 13 | Operative approach | Laparoscopy, laparoscopy converted to open, open |

| 14 | Primary operation performed | Hartmann’s, left hemicolectomy, right hemicolectomy, subtotal colectomy, panproctocolectomy, anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, small bowel resection, complete gastrectomy, partial gastrectomy, oesophagectomy, Whipple’s, other (free text) |

| 15 | Elective or emergency | Elective, emergency |

| 16 | Anastomosis performed | Handsewn, stapled, stoma |

| 17 | Stoma formation | Planned temporary, permanent, none |

| 18 | Underlying pathology/indication | Diverticular disease, hernia, malignancy, polyp, ischaemic bowel, adhesional obstruction, faecal perforation, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, postoperative complication, other |

| 19 | Highest postoperative glycaemic reading within 72 h of surgery using finger prick, blood gas or laboratory value (mmol/L) | Value (mmol/L) |

| 20 | Postoperative critical care admission? | Planned from the theatre, unplanned from the theatre, unplanned from the ward, none |

| 21 | Postoperative ERAS pathway used? | Yes, no |

| 22 | Was an NSAID used postoperatively? | Yes—ibuprofen, yes—diclofenac, yes—naproxen, yes—celecoxib, yes—rofecoxib, yes—other, no |

| 23 | What day was the first dose of NSAID given? | Day 1–7 (day 1 is day of surgery), none given |

| 24 | What dose of NSAID was given? | Low, high, none given |

| 25 | Total length of stay (days) | Days |

| 26 | 30-day readmission? | Yes, no |

| 27 | Surgical complication grade (Clavien-Dindo classification, list most severe grades I–V) | None, I, II, III, IV, V |

| 28 | Anastomotic leak | Yes, no |

| 29 | Wound infection | Yes, no |

| 30 | Intra-abdominal/pelvic abscess | Yes, no |

| 31 | Cardiovascular event | Yes, no |

ASA, American society of anesthesiologists; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Anticipated minimum recruitment

It is estimated that an average centre performs approximately 15 GI resections in a 14-day period. A minimum of 60 centres will be recruited, with at least two centres participating at each of the 30 medical schools. Overall, we anticipate recruiting at least 900 patients.

Power calculation

The study will have at least 80% power to detect an increase in the 30-day adverse event rate from 15% to 25% with NSAID use. It is anticipated that a third of the patients will receive NSAIDS.4 A baseline complication rate of 15% was used to determine the sample size, acting as a midpoint between high and low rates from various subgroups undergoing bowel resection. This rate was based on a recent audit of emergency appendicectomy in the UK, a combination of elective and emergency surgery, and known morbidity profiling.10 13 By recruiting 300 patients receiving NSAIDs and 600 control patients, this study will have 93.5% power to detect an increase in the complication rate from 15% to 25% (α=0.05).

Statistical analysis

Differences between demographic groups will be tested with the χ2 test. Multivariable binary logistic regression will be used to test the influence of clinically plausible variables on the outcome measures, to produce adjusted OR and bootstrapped 95% CI. These tests will be performed firstly on the whole dataset and then on a matched group of 2:1 control : experimental (NSAID administration), using propensity scoring. Data handling will be performed in SPSS V.21.0 and statistical modelling in the R Foundation Statistical Programme 3.0.0.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval

Following the Research Ethics Committee Chairperson's review, a formal waiver was received. The study will be undertaken as a clinical audit. This was further supported by written advice from a University NHS Trust Research & Development Office Director and the National Research Ethics Service (NRES). This study will be registered as a clinical audit or service evaluation at each participating hospital.

Protocol dissemination

The generic collaborative methodology underlying protocol dissemination and collaborator recruitment has been described previously.9 The protocol will be disseminated primarily through medical student networks, including student surgical and medical societies. The Association of Surgeons in Training (http://www.asit.org) will also disseminate the protocol to its members. A student local lead will be designated at each medical school to facilitate local dissemination. The protocol document will be made available online and will also be disseminated through social media, including Twitter (https://twitter.com/STARSurgUK) and Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/STARSurgUK).

Discussion

This paper describes the protocol for a novel study, addressing an important clinical question using rapid-delivery, snapshot methodology. The development of the national network, formed by the natural geographical locations of medical schools within the UK, is also novel. The observational nature of this study means it is classified as an audit. Within the confines of this, a detailed and protocolised approach is warranted to ensure maximum quality.

The multicentre nature of this study means that the approaches taken for its design are pragmatic. In particular, the definitions used and the number of data points are designed to aid local investigators to ensure simplicity of delivery, while containing enough detail to answer the relevant clinical question.

A randomised controlled trial would provide the highest level of evidence to guide patients and clinicians towards optimal postoperative analgesic regimes. In order to power these trials, and to justify funding applications, a multicentre observational study is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (http://www.rcseng.ac.uk) is providing complimentary meeting facilities for the training day.

Footnotes

Collaborators : STARSurg Collaborative. The STARSurg Steering Committee prepared this protocol manuscript: DN, SJC, JCDG, MK, CK, JEF, AB.

Contributors: DN and JEF participated in the conception, design, writing and editing of the protocol. SJC, JCDG, MK and CK participated in the design and writing of the protocol. AB participated in the statistical analysis and is the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: A regional meeting grant has been received from the Association of Surgeons in Training (http://www.asit.org) towards the costs of the national collaborator training day.

Competing interests: DN, MBChB, is an academic foundation trainee (year 2) at the Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital. SJC, BSc, is a final year medical student at the University of Leeds Medical School. JCDG, BSc, is a final year medical student at the Cardiff University Medical School. MK, BSc, is a final year medical student at the University of Liverpool Medical School. CK, BSc, is a fifth year medical student at the Imperial College London Medical School. JEF, BA MBChB MRCS, is a general surgery registrar at Barnet Hospital and studying at University College London. AB, MBChB MRCS, is an academic general surgery registrar in the West Midlands Deanery General Surgery Rotation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nygren J, Thacker J, Carli FF, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2012;31:801–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Miranda N, et al. Comparison of morphine, ketorolac, and their combination for postoperative pain: results from a large, randomized, double-blind trial. Anesthesiology 2005;103:1225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauta M, Landsmeer ML, Koren G. Codeine-acetaminophen versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of post-abdominal surgery pain: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Surg 2009;198:256–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein M, Gogenur I, Rosenberg J. Postoperative use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with anastomotic leakage requiring reoperation after colorectal resection: cohort study based on prospective data. BMJ 2012;345:e6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holte K, Andersen J, Jakobsen DH, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitors and the risk of anastomotic leakage after fast-track colonic surgery. Br J Surg 2009;96:650–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorissen KJ, Benning D, Berghmans T, et al. Risk of anastomotic leakage with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2012;99:721–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein M, Krarup PM, Kongsbak MB, et al. Effect of postoperative diclofenac on anastomotic healing, skin wounds and subcutaneous collagen accumulation: a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, experimental study. Eur Surg Res 2012;48:73–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein M. Postoperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colorectal anastomotic leakage. NSAIDs and anastomotic leakage. Dan Med J 2012;59:B4420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhangu A, Kolias AG, Pinkney T, et al. Surgical research collaboratives in the UK. Lancet 2013;382:1091–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horan TC, Andrus A, Dudeck MA, et al. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999;100:1043–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Surgical Research Collaborative. Multicentre observational study of performance variation in provision and outcome of emergency appendicectomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:1240–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.