Abstract

Objective

This study estimated the health impact, cost and cost-effectiveness of an integrated prevention campaign (IPC) focused on diarrhoea, malaria and HIV in 70 countries ranked by per capita disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) burden for the three diseases.

Methods

We constructed a deterministic cost-effectiveness model portraying an IPC combining counselling and testing, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, referral to treatment and condom distribution for HIV prevention; bed nets for malaria prevention; and provision of household water filters for diarrhoea prevention. We developed a mix of empirical and modelled cost and health impact estimates applied to all 70 countries. One-way, multiway and scenario sensitivity analyses were conducted to document the strength of our findings. We used a healthcare payer's perspective, discounted costs and DALYs at 3% per year and denominated cost in 2012 US dollars.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was cost-effectiveness expressed as net cost per DALY averted. Other outcomes included cost of the IPC; net IPC costs adjusted for averted and additional medical costs and DALYs averted.

Results

Implementation of the IPC in the 10 most cost-effective countries at 15% population coverage would cost US$583 million over 3 years (adjusted costs of US$398 million), averting 8.0 million DALYs. Extending IPC programmes to all 70 of the identified high-burden countries at 15% coverage would cost an adjusted US$51.3 billion and avert 78.7 million DALYs. Incremental cost-effectiveness ranged from US$49 per DALY averted for the 10 countries with the most favourable cost-effectiveness to US$119, US$181, US$335, US$1692 and US$8340 per DALY averted as each successive group of 10 countries is added ordered by decreasing cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

IPC appears cost-effective in many settings, and has the potential to substantially reduce the burden of disease in resource-poor countries. This study increases confidence that IPC can be an important new approach for enhancing global health.

Keywords: Health Economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Synthesises a large volume of epidemiological data from disparate sources into a unified method for projecting the consequence of integrated prevention campaign (IPC) implementation in 70 countries.

Links the ‘opportunity index’ concept with cost-effectiveness.

Provides a more comprehensive assessment of intervention potential than assessment of cost-effectiveness alone.

Methods presented here may be applied to other disease areas and facilitate more objective resource allocation decision-making for global health.

Incomplete availability of data relevant to the large number of countries analysed.

Infeasible to develop cost-effectiveness thresholds that reflected the full array of local public health options against which IPC could be considered.

Regions or urban areas within countries may have costs and health benefits that depart from the overall country assessments.

Background

For many years, vertical (disease-specific) programming has dominated the sphere of global health funding in an effort to tackle the areas of greatest need.1 However, there is increasing recognition that, among diseases with complementary prevention strategies and overlapping populations, single-disease approaches to population health improvement create duplication of effort and miss important opportunities for synergies in health benefits and economies of scope.2 Recent initiatives have therefore sought to integrate programmes for multiple diseases, and many have demonstrated feasibility, efficiencies and success.3 4

A particularly promising example of integrated programming was a prevention campaign in Western Province, Kenya that targeted diarrhoea, malaria and HIV,5 three diseases that account for a substantial portion of the total disease burden in many parts of the developing world.6 Over the course of 1 week, the campaign provided general health education, condoms, insecticide-treated bed nets, point-of-use water filters and HIV testing and counselling to more than 80% of the target population.5 Those testing positive for HIV were offered on-site CD4 count determination, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and referral to comprehensive HIV care and treatment. The campaign yielded large health benefits and net economic savings.7 8 Large-scale expansion of this integrated prevention campaign (IPC) has the potential to deliver substantial health benefits and cost savings. In a separate study, we reviewed country-specific data for 70 low-income and middle-income countries, finding that the opportunity for a diarrhoea, malaria and HIV IPC is not limited to Kenya.9 It is plausible that IPCs can have a large impact on health in many resource-limited settings.

While the cost-effectiveness of this IPC in Western Kenya has been established8 the economic and health effects of a multicountry IPC initiative are unknown. Using data appropriate for providing an initial indication of the conditions under which IPC is likely to be cost-effective, we estimated the costs, health outcomes and cost-effectiveness of IPC implementation in the same 70 low-income and middle-income countries. To support decision-making for IPC implementation, we also estimate the increases in budgets that would be required to cover increasing numbers of countries.

Methods

Overview

We modelled the health impact, cost and cost-effectiveness of a diarrhoea, malaria and HIV IPC in 70 countries by adapting a previously published spreadsheet-based model that was applied to the original IPC in Western Kenya.8 Countries were chosen for inclusion in the analysis based on two factors: they were classified as low-income or middle-income as defined by the World Bank10; and they had a total disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) burden for the three diseases addressed by the IPC in the highest tertile of the 214 World Bank-defined economies (ie, ≥87 000 DALYs); as described in a companion paper.9 We refer to this ordering of countries by the combined disease burden as the ‘opportunity index’. For a break-down of the relative contribution by disease to each country's total burden see Jiwani 2014 and table S4 of the online technical supplement. We derived incidence and case death rates for each country from published reports, using regional averages and other approximations when country-specific estimates were missing. We developed a mix of empirical (where available) and modelled (projected from empirical data) cost estimates applied to all 70 countries. Key outcomes examined included the cost of the IPC; net IPC costs adjusting for averted and additional medical costs; deaths and disease episodes averted; DALYs averted due to prevention, and to earlier and more HIV care; and finally, cost-effectiveness expressed as net cost per DALY averted. We used a healthcare payer's perspective, and discounted long-term costs and DALYs at 3% per year.11 Costs were denominated in 2012 US dollars. The time frame of the analysis is 3 years for the empirical data. Modelled results depend on the age-dependent life expectancy at the time death would otherwise have occurred in Kenya. This is 61 years for diarrhoeal diseases and malaria, and 37 years for HIV.

Detailed model features

We adapted a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that we had previously constructed to analyse the cost-effectiveness of the Kenya IPC. Details of the model have been published elsewhere.8 The model estimates the health and cost benefits of prevention for malaria, diarrhoea and HIV separately. For HIV, it also estimates the DALYs averted and costs incurred due to earlier diagnosis and treatment arising from HIV testing. Cost-effectiveness of the IPC was compared to the cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in each of the 70 countries. This metric was selected since, with the current aspiration of universal access to ART,12 provision of ART is on the active policy agenda for most HIV-affected countries.

Cost estimates and projection methods

Campaign costs for the Kenya IPC were obtained from published empirical data supplemented by filter repair and replacement costs.7 8 We estimated campaign costs for each country using the Kenya IPC as a benchmark, translating to other countries according to type of cost, as follows. Programme costs were classified as commodity, personnel and other costs. Commodities were further categorised as tradable and non-tradable. Tradable commodities are those purchased on the international market and include bed nets, filters and condoms, and required no adjustment from the dollar-denominated costs incurred by the Kenya IPC.7 The cost of non-tradable items, primarily personnel, were adjusted according to the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) ratio, in International dollars, between Kenya and each study country.13 For each country, we estimated the costs of averted medical care due to the IPC by adjusting the costs for healthcare incurred per fatal and non-fatal case in the Kenya campaign by the ratio of GDP per capita in the target country versus Kenya. We selected per capita GDP rather than per capita healthcare spending as the basis for these adjustments, because the latter reflects overall access to care and our model accounts for access separately. (For a comparison of 3 cost adjustment methods and evidence of similar resulting cost estimates, see online technical supplement.)

There are few country-specific data on access to care for malaria except for some of the more-affected countries, mostly in Africa. We therefore used global average rates of treatment access, estimated at 68.4% based on published literature.14–19 (See online technical appendix for the country-specific figures underlying this value.) As noted in table 2, the value of 68.4% was varied from 51.3% to 85.5% in sensitivity analyses. For access to care for diarrhoea, we used country-specific estimates based on demographic and health survey data on the percentage of children under 5 years of age with diarrhoea in the 2 weeks preceding the survey who received any kind of treatment for diarrhoea.20 We used an average rate of access to ART of 70%. This is considerably higher than the 56% access reported for sub-Saharan Africa21 and reflects likely increases in the context of the global commitment to access.12

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis variables, base case, minimum and maximum values

| Input parameter | Nigeria |

Kenya |

Bangladesh |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | Min | Max | Base case | Min | Max | Base case | Min | Max | |

| Campaign cost | US$40 479 | US$20 239 | US$60 718 | US$34 280 | US$17 140 | US$51 420 | US$35 658 | US$17 829 | US$53 486 |

| Cost per death malaria | US$97.50 | US$48.75 | US$146.25 | US$65.00 | US$32.50 | US$97.50 | US$72.22 | US$36.11 | US$108.33 |

| Cost per death diarrhoea | US$156.00 | US$78.00 | US$234.00 | US$104.00 | US$52.00 | US$156.00 | US$115.56 | US$57.78 | US$173.34 |

| Cost per non-fatal case malaria | US$11.70 | US$5.85 | US$17.55 | US$7.80 | US$3.90 | US$11.70 | US$8.67 | US$4.33 | US$13.00 |

| Cost per non-fatal case diarrhoea | US$10.50 | US$5.25 | US$15.75 | US$7.00 | US$3.50 | US$10.50 | US$7.78 | US$3.89 | US$11.67 |

| Annual cost ART | US$938 | US$469 | US$1407 | US$766 | US$383 | US$1150 | US$766 | US$383 | US$1150 |

| Discount rate | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.045 |

| Access to care diarrhoea | 0.565 | 0.424 | 0.706 | 0.678 | 0.509 | 0.848 | 0.663 | 0.497 | 0.829 |

| Access to care malaria | 0.684 | 0.583 | 0.855 | 0.684 | 0.583 | 0.855 | 0.684 | 0.583 | 0.855 |

| Access to ART | 0.7 | 0.42 | 0.98 | 0.7 | 0.42 | 0.98 | 0.7 | 0.42 | 0.98 |

| Years on ART | 22 | 11 | 33 | 22 | 11 | 33 | 22 | 11 | 33 |

| HIV prevalence | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.095 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.0009 |

| Baseline cases p1000py Malaria | 351.6 | 175.8 | 527.5 | 57.0 | 28.5 | 85.5 | 6.13 | 3.06 | 9.19 |

| Baseline cases p1000py diarrhoea | 765.3 | 382.7 | 1148.0 | 542.0 | 271.0 | 813.0 | 299.81 | 149.91 | 449.72 |

| Propor fatal malaria | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| Propor fatal diarrhoea | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0011 |

| Participants per HH | 2.5 | 1.25 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 3.75 |

| DALYs fatal malaria | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 |

| DALYs fatal diarrhoea | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 | 27.8 | 13.9 | 41.7 |

| DALYs non-fatal malaria | 0.366 | 0.183 | 0.549 | 0.366 | 0.183 | 0.549 | 0.366 | 0.183 | 0.549 |

| DALYs non-fatal diarrhoea | 0.127 | 0.064 | 0.191 | 0.127 | 0.064 | 0.191 | 0.127 | 0.064 | 0.191 |

| Protect. mortality malaria | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 |

| Protect. mortality diarrhoea | 0.630 | 0.315 | 0.945 | 0.630 | 0.315 | 0.945 | 0.630 | 0.315 | 0.945 |

| Protect. non-fatal malaria | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 |

| Protect. non-fatal diarrhoea | 0.628 | 0.314 | 0.941 | 0.628 | 0.314 | 0.941 | 0.628 | 0.314 | 0.941 |

| Protect. mortality HIV transmission | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.750 |

| Protect. mortality HIV acquisition | 0.255 | 0.128 | 0.383 | 0.255 | 0.128 | 0.383 | 0.255 | 0.128 | 0.383 |

| Multiplier: secondary effects HIV | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Duration of benefit malaria | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| Duration of benefit diarrhoea | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 3 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| Duration of benefit HIV | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

All variables have β distributions with α and β parameters of 2. Minimum and maximum values are 0.5 and 1.5 of base case values, respectively, except for access to diarrhoea disease care and malaria care which have minimum and maximums of 0.6 and 1.4, and access to HIV ART which has a minimum and maximum of 0.75 and 1.25. Bold figures represent values that change with each country.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year.

We calculated the per person-year cost of ART for each country by using published estimates for countries where available.22–42 The non-drug portion of each published unit cost figure was inflated to 2012 US dollars using the USA Consumer Price Index.43 We then derived from the set of published figures an average figure for low income, lower middle income excluding India and upper middle income countries as defined by the World Bank.44 We applied these country income-category averages to the larger set of countries for which published ART unit cost estimates were unavailable, according to their respective income categories. ART cost-effectiveness for each country was estimated by adjusting US$883 per DALY averted which is the average for 45 sites studied in Zambia.26 To arrive at country-specific estimates we calculated the ratio of per capita income between each country and Zambia and applied this factor to the average portion of overall ART costs for low-income countries which is non-tradable, 36.9%. This figure was derived from the ART unit cost studies described above which includes the breakdown of costs by major component.

First versus second campaign health benefits

The health benefits of a second campaign are likely to be lower than that of the initial campaign. For malaria this is due to residual benefits from nets, beyond their average functional life of 3 years. In the absence of a second campaign, we assume a malaria risk in years 4–6 equal to 75% of the risk at baseline (before the first campaign). For diarrhoeal disease the filters themselves are not expected to confer benefit after 3 years, though there may be residual benefit from the behavioural component; we assume that the risk is 87.5% of baseline. New nets and filters in a second campaign reduce disease risks to the levels expected after the first campaign. Thus the second campaign reduces the incidence of malaria from 75% to 50% of baseline (a 1/3 relative reduction). Similarly, diarrhoea decreases from 87.5% to 37% of baseline (a relative drop of 58%; details in online technical supplement).

Disease-specific data and projection methods

We obtained country estimates of the prevalence of HIV in the adult (15−49 years) population.42 45 46 For each country, we derived estimates of the baseline cases of malaria per person-year by dividing WHO-adjusted estimates of the annual number of cases47 by the total country population.48 For diarrhoea, we estimated the average number of cases per person-year in the overall population using DHS data on the number of cases per year in children under 549 (details in online technical supplement).50 51 Multiplying each estimate by the total population48 yields the estimated number of cases in each country.

We calculated country-specific case death rates for malaria and diarrhoea as the number of deaths due to the disease52 53 divided by the number of cases. We set an upper-bound malaria case death rate of 15% based on published findings of a Delphi survey of malaria experts.54 We assumed a case death rate for HIV of 100%.

Using a discount rate of 3%55 we estimated the DALYs incurred with each fatal case of malaria and diarrhoea at 28 based on life expectancy at age 25 in Kenya (the estimated average age of death from malaria and diarrhoea) of 61 years.56 We derived estimates of the DALYs incurred per non-fatal case of each disease as the product of the disability weight (0.191 for malaria and 0.105 for diarrhoea)57 and the average duration of each case (7 days for malaria58; 4.43 days for diarrhoea, a severity weighted duration for children and adults59; or 0.0037 and 0.0013 DALYs for each non-fatal case of malaria and diarrhoea, respectively. Assuming 70% access to ART, we estimated 10.6 DALYs incurred per HIV infection, and 8.8 discounted DALYs averted per treated case of HIV, an assumption based on 22 years of ART, average age of ART initiation of 35 years, and a life expectancy at age 35 in Kenya of 37 years.56 Each untreated HIV case incurs 15.1 discounted DALYs.

Household size and beneficiaries per household

Using country-specific data of rural household size as reported in the most recent Demographic and Health Survey, divided by the number of participants per household as observed in the Kenya IPC campaign, we obtained the number of beneficiaries per campaign participant. For bednets, we assumed fewer incremental beneficiaries per participant on the assumption that there was some prior access to bednets, 15.1% on average, as observed in the Kenya campaign. For HIV we assumed the same number of adult participants on average, 2.5, as the basis for calculating the number of beneficiaries per campaign participant.

For the remaining health inputs, we assumed values equal to those used in the Kenya analysis for all countries.8 See table 1 for base case values and sources for data inputs.

Table 1.

Base case values and sources for data inputs

| Malaria | Diarrhoea | HIV |

Source(s) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLIN | Filters | VCT | Condoms | LLIN | Filters | VCT/condoms | |

| Health in61puts | |||||||

| Campaign participant per household | 2.5 | Postcampaign survey | |||||

| Number benefiting per campaign participant | 1.563 | 1.840 | 0.950 | 0.361 | Postcampaign survey | ||

| Baseline cases per year per individual benefiting | 0.057 | 0.542 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 47, 48 | 49–51 |

8,

62–64 Postcampaign survey (see text) |

| Proportion of cases that are fatal | 0.012 | 0.001 | 1 | 1 | 47, 52, 54 | 48, 49, 51, 59, 62 | Assumption |

| DALYs incurred with each fatal case | 28.0 | 28.0 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 56 | 56 | 56 |

| DALYs incurred with each non-fatal case | 0.0037 | 0.0012 | NA | NA | 57, 58 | 57, 59 | NA |

| Protective effect against mortality | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.26 | Expert opinion65 | 66 | 67, 68 |

| Protective effect against non-fatal cases | 0.5 | 0.63 | NA | NA | 65 | 66 | NA |

| Multiplier to capture secondary benefits | NA bit | NA | 2 | 2 | 69 | NA | 70 (see text) |

| Years of benefit | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Adjusted to 3 years per postcampaign evaluation71 72 | Adjusted to 3 years per postcampaign evaluation73 | 68 |

| Access to care | 0.684 | 0.678 | 0.700 | 0.700 | 14–19 | 20 | Assumption |

| Cost inputs | |||||||

| Campaign cost | US$34 280 | US$31 980 plus additional US$2300 in revised filter maintenance costs7 | |||||

| Discount rate | 3.0% | 10 | |||||

| Healthcare incurred with each death | US$65 | US$104 | US$12 213 | US$12 213 | 64, 74 | 75 | Authors’ construction based on 22 years on ART at US$766 per person-year discounted at 3% per annum. |

| Healthcare incurred with each non-fatal case | US$7.80 | US$7.00 | NA | NA | 76 | 75 | NA |

Bold figures represent values that change with each country.

DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; NA, not applicable.

Relationship of opportunity to cost-effectiveness

In a companion article, we identified the countries in which scale-up of a diarrhoea, malaria and HIV IPC would be most beneficial, by summarising country-specific epidemiological data related to the disease burden and shortfall in current intervention coverage (Jiwani et al, under review, 2013). We created three ‘opportunity indices,’ ranking countries by (1) DALYs per capita across the three diseases of the IPC, (2) a sum of burden ranks for each disease and (3) a composite of burden and intervention opportunity. We extend this opportunity analysis by examining the relationship between a country's opportunity rank (in DALYs per capita) and its cost-effectiveness for IPC implementation.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess the effect of uncertainty in inputs, we conducted one-way and multiway Monte Carlo sensitivity analyses for three countries: Kenya, a low-income country where the IPC trial was performed and is at the 44th centile for cost-effectiveness of the 70 countries analysed; Nigeria, a lower-middle income country at the 75th centile (relatively favourable); and Bangladesh, a low-income country at the 25th centile. Each of the 31 model inputs examined in the sensitivity analyses (table 2) was assigned a β distribution with α and β parameters of 2, in order to ensure symmetry around the mean. Maximum and minimum values were set as 1.5 and 0.5 times the base case, except for access to malaria and diarrhoea treatment (0.75–1.25 of base case) and access to HIV treatment (0.6–1.4 times base case). Figures in bold font reflect parameter values that vary by country. Finally, we examined the effect of variations in important inputs on the cost-effectiveness of IPC in all 70 countries grouped in order of cost-effectiveness.

Results

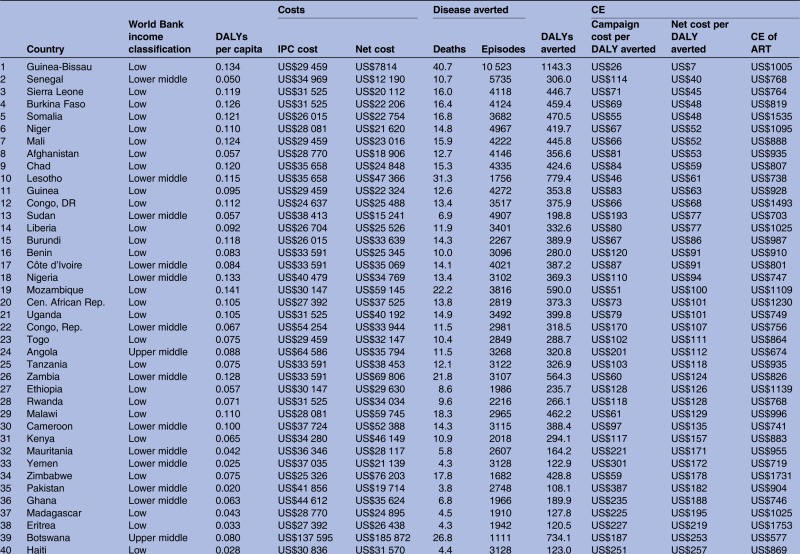

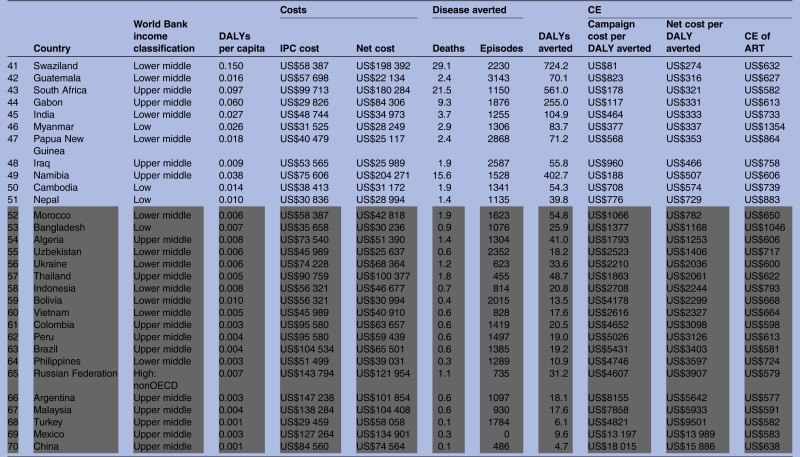

Across the 70 high-opportunity countries, the cost-effectiveness of the first campaign ranges from US$7 (Guinea-Bissau) to US$15 886 (China) per DALY averted (IQR US$96–US$1071 per DALY averted; table 3). At US$182 per DALY averted, Pakistan is at the 50th centile for cost-effectiveness. With the exception of Afghanistan, the 30 counties with the most favourable cost-effectiveness are in sub-Saharan Africa. The cost-effectiveness of IPC compares favourably to the cost-effectiveness of ART in 51 countries. The 30 countries with the lowest cost-effectiveness estimates are geographically more diverse and include only three in sub-Saharan Africa (Swaziland, South Africa and Namibia).

Table 3.

Summary costs and cost-effectiveness results per 1000 IPC participants for 70 countries ordered from most favourable to least favourable cost-effectiveness (net cost per DALY averted)

|

|

The grey highlighted cells indicate CE ratio is less favourable than investment in ART. Results shown are for the first 3-year campaign.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CE, cost-effectiveness; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; IPC, integrated prevention campaign.

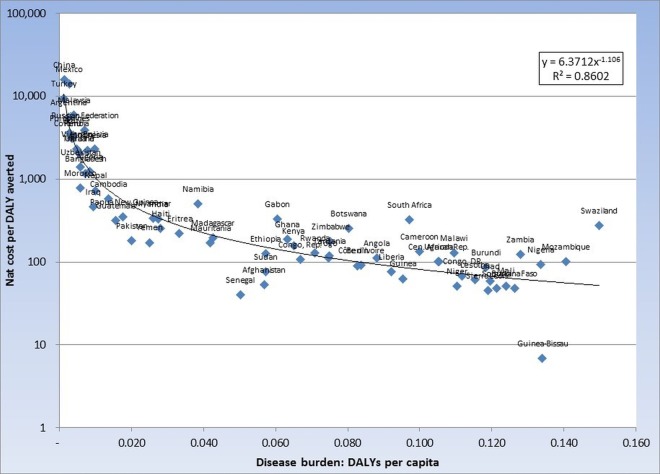

As shown in figure 1, per capita disease burden as measured by the opportunity index is highly correlated with cost-effectiveness. See figure 1 of the online technical supplement for relationship between opportunity index and cost-effectiveness for campaign 2.

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness (net integrated prevention campaign (IPC) cost per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) averted) and Opportunity Index (DALYs per capita; Campaign 1, n=70).

Table 4 displays the cumulative results, grouped in 10-country increments, assuming 15% population coverage and moving from most to least attractive cost-effectiveness. IPC in the top 10 countries would cost US$583 million for the 3-year campaign, with a net cost after adjusting for effects on healthcare spending of US$398 million for the first 3-year campaign and US$468 million for the second and subsequent campaigns. The first and second campaigns would avert 8.0 and 5.7 million DALYs, respectively, with an average cost-effectiveness of US$49 and US$82 per DALY averted, respectively. As shown in the right-hand two columns, the incremental cost-effectiveness rises rapidly (becomes less favourable) after coverage of the top 50 countries. In particular, if expanding from the top 50 to 60 countries and from 60 to all 70 countries, large net incremental costs are associated with relatively modest increases in health benefits. The cost per DALY averted in expanding from 60 to 70 countries is US$8340 and US$19 728 for campaigns 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 4.

IPC costs, DALYs averted and cost-effectiveness compared with no intervention, and incremental cost-effectiveness for 70 countries in increments of 10, ranked by cost-effectiveness US$

| Countries | Campaign cost | Net cost |

DALYs averted |

Cost-effectiveness (compared with no intervention) |

Incremental cost-effectiveness (compared with previous row) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign 1 | Campaign 2 | Campaign 1 | Campaign 2 | Campaign 1 | Campaign 2 | Campaign 1 | Campaign 2 | ||

| Top 10 | 5.832E+08 | 3.979E+08 | 4.685E+08 | 8.048E+06 | 5.708E+06 | US$49 | US$82 | NA | NA |

| Top 20 | 2.387E+09 | 2.054E+09 | 2.068E+09 | 2.706E+07 | 1.629E+07 | US$76 | US$127 | US$87 | US$151 |

| Top 30 | 3.715E+09 | 3.554E+09 | 3.338E+09 | 3.961E+07 | 2.382E+07 | US$90 | US$140 | US$119 | US$169 |

| Top 40 | 5.614E+09 | 4.943E+09 | 4.858E+09 | 4.731E+07 | 2.916E+07 | US$104 | US$167 | US$181 | US$284 |

| Top 50 | 1.624E+10 | 1.342E+10 | 1.395E+10 | 7.265E+07 | 4.983E+07 | US$185 | US$280 | US$335 | US$440 |

| Top 60 | 2.226E+10 | 1.863E+10 | 1.941E+10 | 7.573E+07 | 5.186E+07 | US$246 | US$374 | US$1692 | US$2699 |

| Top 70 | 5.129E+10 | 4.350E+10 | 4.629E+10 | 7.871E+07 | 5.322E+07 | US$553 | US$870 | US$8340 | US$19 728 |

‘Net costs’ consist of IPC campaign costs adjusted for medical costs averted or added due to the campaign. Results assume 15% of population covered by IPC in each country. Costs in 2012 US dollars.

DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; IPC, integrated prevention campaign; NA, not applicable.

For each stratum of 10 countries ranked from most to least cost-effective, table 5 displays the median cost-effectiveness for the first 3-year campaigns, for possible second campaigns, and for ART. The cost-effectiveness of the first campaign compares more favourably to ART by a wide margin for each of the 10-country strata. For the second campaign ART is more cost-effective than IPC for the 51st–60th and for the 61st–70th country, as ranked by IPC cost-effectiveness.

Table 5.

Median cost-effectiveness (net cost per DALY averted) by 10-country increments in order of cost-effectiveness

| Countries ranked by IPC cost-effectiveness | Campaign 1 | Campaign 2 | Antiretroviral therapy for HIV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10 | US$50 | US$102 | US$854 |

| 11–20 | US$88 | US$141 | US$958 |

| 11–30 | US$121 | US$197 | US$797 |

| 31–40 | US$185 | US$318 | US$894 |

| 41–50 | US$335 | US$591 | US$683 |

| 51–60 | US$1721 | US$3514 | US$666 |

| 61–70 | US$4774 | US$17 068 | US$587 |

DALY, disability-adjusted life-year.

Results for Kenya, Bangladesh and Nigeria illustrate reasons for variation across countries.

In Nigeria, the IPC cost-effectiveness ratio is US$94 per DALY averted, 18th of 70 countries ranked by cost-effectiveness. This result represents high health benefits for malaria and diarrhoea, and modest benefits for HIV. For every 1000 IPC participants, the first campaign averts an estimated 13.4 deaths: 6.0 due to malaria, 3.4 due to diarrhoea and 4.0 due to HIV. The campaign costs are US$40 479, with net costs of US$34 769 after offsetting savings from averted care needs.

In Kenya, cost-effectiveness is somewhat less attractive, at US$157 per DALY averted, 31st of 70 countries. This is due to lower malaria and diarrhoea benefits than in Nigeria, and more discovered HIV. For every 1000 IPC participants, the campaign averts an estimated 10.9 deaths: 1.6 due to malaria, 2.4 to diarrhoea and 7.0 to HIV. The campaign costs US$34 280. Although reduced disease creates offsetting savings in care needs, there are US$81 000 in added HIV costs due to earlier and additional detection of HIV. The net cost of the campaign is US$46 149, or US$157 per DALY averted. This is less than the US$883 per DALY averted for ART in Kenya.

In Bangladesh, the IPC cost-effectiveness ratio is US$1168 per DALY averted, 53rd of 70 countries. This is due to lower health benefits overall. For every 1000 IPC participants, the campaign averts an estimated 0.9 deaths: 0.1 due to malaria, 0.8 due to diarrhoea, and only 0.1 due to HIV. The campaign costs are US$35 658. When adjusted for modest offsetting savings from averted care, the net cost of the campaign is US$30 236. Cost-effectiveness is comparable with the estimated US$1046 per DALY averted for ART for HIV. See table 5 of the online technical supplement for detailed results for all three countries.

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analysis

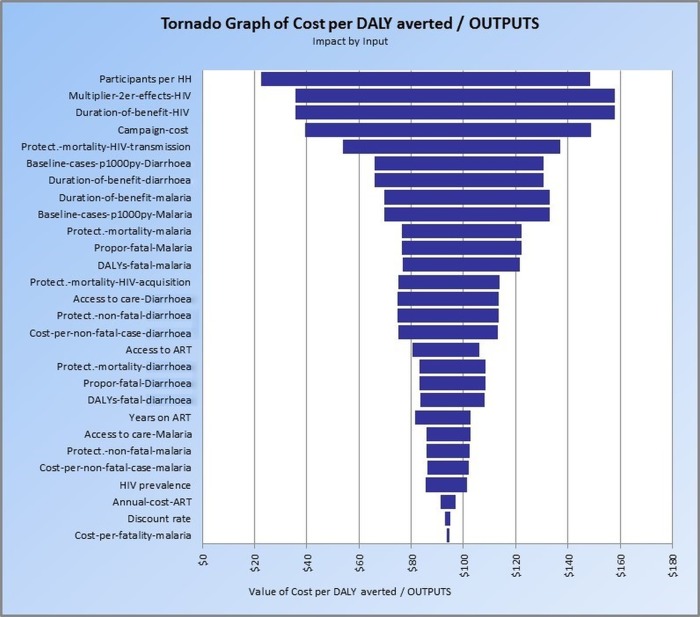

Figure 2 is a tornado graph of the sensitivity of IPC cost-effectiveness to the model inputs displayed in table 2 for Nigeria. IPC participants per household had the greatest effect on IPC cost-effectiveness (range, US$126 per DALY averted), followed by the multiplier that reflects prevention of secondary HIV transmission, the duration of the prevention benefits of HIV interventions (range, US$122 per DALY averted each), cost of the IPC campaign (range, US$110 per DALY averted), and the reduction in mortality due to reduced HIV transmission (range, US$83 per DALY averted).

Figure 2.

Tornado graph of Cost per DALY averted—Nigeria: impact by input (ART, antiretroviral therapy; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year).

For Bangladesh, the inputs with the greatest effect on cost-effectiveness are duration of benefits for diarrhoea prevention and the baseline cases of diarrhoea per 1000 person-years (range, US$1506 per DALY averted for both), campaign cost (range, US$1377 per DALY averted), IPC participants per household (range, US$1305 per DALY averted) and protective benefit against diarrhoea mortality (range, US$1140 per DALY averted). For Kenya, the variables with the most influence on cost-effectiveness are the multiplier that reflects prevention of secondary HIV transmission and the duration of the prevention benefits of HIV interventions (range, US$236 per DALY averted each), the reduction in mortality due to reduced HIV transmission (range, US$161 per DALY averted), cost of the IPC campaign (range, US$117 per DALY averted) and the number of participants per household (range, US$103 per DALY averted). See online technical supplementary figures S2 and S3 for one-way sensitivity analysis tornado graphs for Bangladesh and Kenya, respectively.

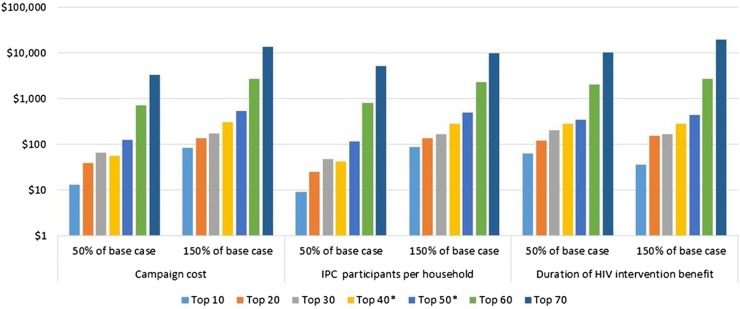

Figure 3 shows how variation in three inputs affects incremental cost-effectiveness as each successive 10 countries are added to a scaled-up IPC programme. Up to 50 countries, IPC remains cost-effective compared with ART even if the least favourable end of the input estimate range is used.

Figure 3.

One-way sensitivity analysis of incremental cost-effectiveness by three key variables in 10-country increments ranked by integrated prevention campaign (IPC) cost-effectiveness.

Multivariate Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis

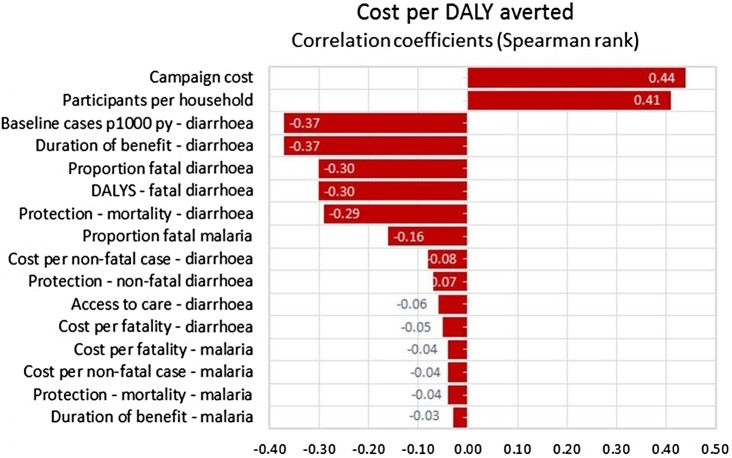

Table 6 displays the 80% CI for a 20 000-trial simulation for three outcomes: DALYs averted, net costs and net cost per DALY averted (cost-effectiveness). For Kenya and Nigeria the least favourable end of the cost-effectiveness range is more favourable than the cost-effectiveness of ART for HIV, US$304 vs US$883 per DALY averted for Kenya and US$208 vs US$747 per DALY averted for Nigeria. For Bangladesh, the least favourable end of the cost-effectiveness range, US$2547 is less favourable than the estimated US$1046 per DALY averted for ART. For Nigeria the five most important variables in order of their correlation with cost-effectiveness (net cost per DALY averted) are, the duration of the HIV prevention benefits (r=−0.51); prevention of secondary HIV transmission (r=−0.50), the number of IPC participants per household (r=0.33), cost of the IPC campaign (r=0.31), and the reduction in mortality due to reduced HIV transmission (r=−0.24; figure 4). See online technical supplementary figures S4 and S5 for multivariate sensitivity analyses correlations coefficients for Kenya and Bangladesh, for projection of IPC costs and benefits in Kenya for 30 years (see online technical supplementary figure S6).

Table 6.

Multiway sensitivity analysis; 20 000-trial Monte Carlo simulation, 80% CI for three IPC outcomes and cost per DALY averted by ART for HIV in Kenya, Bangladesh and Nigeria

| Outcomes | Kenya | Bangladesh | Nigeria |

|---|---|---|---|

| DALYs averted | 206–407 | 13.1–45.8 | 228–564 |

| Net costs | US$7810–US$79 885 | US$18 566–US$41 473 | US$2241–US$61 448 |

| Net cost per DALY averted (cost-effectiveness) | US$23–US$304 | US$519–US$2547 | US$5–US$208 |

| Cost per DALY averted by ART for HIV | US$883 | US$1046 | US$747 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; IPC, integrated prevention campaign.

Figure 4.

Result of 20 000-trial Monte Carlo simulation: correlation between input values and cost per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) averted—Nigeria.

Scenario analysis

IPC cost-effectiveness with HIV costs and outcomes omitted. Finally, we report on the cost and cost-effectiveness of the IPC programme if HIV programme costs and health benefits are ignored. These results reflect the perspective of a payer who assumes responsibility for the diarrhoea and malaria components only. When future HIV-related costs and benefits are disregarded, including both additional care costs due to more and earlier detection and reductions in care costs due to prevention, the cost per DALY averted decreases from US$157 to US$129 in Kenya; from US$94 to US$31 in Nigeria and increases from US$1168 to US$819 in Bangladesh.

Discussion

We examined the costs and health benefits of IPC for 70 countries with a high combined burden of diarrhoea, malaria and HIV. Together these countries comprise 76% of the world population48 50 and 98% of its disease burden.9 If implemented with 15% population coverage in the top 40 of the 70 countries as ordered by cost-effectiveness, 47.3 million DALYs could be averted at a net cost of US$4.9 billion, or US$104 per DALY averted. As shown in table 3, this compares favourably with the cost-effectiveness of ART in each of those 40 countries. The DALYs averted constitute 58% of the disease burden due to HIV, malaria and diarrhoeal disease in these countries. US$4.9 billion is considerably less than the President's request to the USA Congress for FY 2013 for US$6.4 billion for the PEPFAR programme60 and thus might be affordable from a donor's perspective, especially if the current trend of greater host country financial contribution to HIV programmes continues. With the exception of Afghanistan, all 30 of the countries in which IPC was most cost-effective are in sub-Saharan Africa and in 51 countries, the cost-effectiveness of IPC compared favourably to ART.

The cost-effectiveness of IPCs varies greatly among the 70 countries we examined. This wide divergence is due primarily to differences in disease burden and therefore to the higher levels of incremental health benefit generated per incremental dollar spent for prevention. For example, Nigeria ranks 4th of the 70 countries based on DALYs per capita in the three diseases of the IPC, and Bangladesh ranks 55th. As shown in figure 1, per capita disease burden as measured by the opportunity index is highly correlated with cost-effectiveness. In the case of a single disease-intervention pair such a finding would be unsurprising since the cost-effectiveness of most prevention interventions depend importantly on incidence. It is more noteworthy here since the relative prevalence of the three diseases varies greatly between the countries we studied, and the effect on medical care costs of intervening also varies substantially among the three diseases. In spite of this variability, the opportunity index is a reasonably good guide to cost-effectiveness.

Costs of programme delivery also matter. Swaziland, Botswana and South Africa have relatively unfavourable cost-effectiveness in relation to their disease burden. This is due primarily to their high per capita GDP and thus the higher estimated non-commodity (mainly personnel) portion of their campaign costs. However, IPC cost-effectiveness still compares favourably to that of ART in all three countries.

Sensitivity of findings within each country reflects how the IPC interacts with local disease burden. Diarrhoea is the largest contributor to the disease burden in Bangladesh, accounting for 87% of the DALYs averted by the IPC campaign. Not surprisingly, the most important determinant of cost-effectiveness was the estimated duration of the benefits of the water filter and the baseline incidence of diarrhoea. Kenya has a far larger HIV epidemic, with a prevalence of 6.3% rather than 0.06% of adults as in Bangladesh. Accordingly, the largest determinants of IPC cost-effectiveness in Kenya were HIV-related in both one-way and multivariate sensitivity analyses. Nigeria's HIV prevalence of 3.6% is close to the average of 3.5% of the 70 countries examined. Nigeria's high IPC cost-effectiveness ranking is due to its high incidence of malaria and diarrhoea, 252 and 765 cases per 1000 person-years, respectively, compared with median values of 52 and 521 for malaria and diarrhoea respectively for the 70 countries studied.

Among the strengths of the current study are its synthesis of a large volume of epidemiological data from disparate sources into a unified method for projecting the consequence of IPC implementation in 70 countries, and the linking of the ‘opportunity index’ concept with cost-effectiveness. This provides a more comprehensive assessment of intervention potential than assessment of cost-effectiveness alone. This data-driven process may be applied to other disease areas and facilitate more objective resource allocation decision-making.

Limitations of our approach include incomplete availability of data relevant to the large number of countries analysed. Methods for approximation were therefore necessary. For example, the costs of the campaigns themselves were extrapolated from empirical Kenya-specific data using per capita GDP ratios between Kenya and the other countries to estimate the non-tradable commodity portion of costs. For other variables such as the protective effects of HIV prevention, bed nets and water filters where country-specific information was absent we employed wide ranges in the sensitivity analyses to ensure that we accounted for uncertainty, and this produced wide CIs around the model outcomes.

This study provides substantial evidence that IPC campaigns can be cost-effective in a large number of low-income and middle-income countries epidemic settings. However, it leaves unanswered important questions that need to be addressed when these broad findings are translated into programmes and policies. For example, in settings with high prevalence of both HIV and malaria, as community HIV prevalence is reduced, malaria susceptibility may decline, thus reducing the benefits associated with malaria prevention. Such interactions are not accounted for in our analysis. In some countries the relative contributions of each disease to the total burden imposed by all three diseases is uneven9 (see table S4 of the online technical supplement for a breakdown of the contribution of each disease to the total for all three diseases). Swaziland, for example, has a high burden of HIV and a low burden of malaria. In Swaziland and similar settings, it may be sensible to focus the IPC campaign in areas of relatively high malaria endemicity, by other means to target the malaria prevention component. Our cost projections posit relatively low IPC coverage of 15%. At this level it is reasonable to assume that in most countries, many high-prevalence areas would not be fully covered and planners need not be concerned that a point of diminishing returns would be met in which it becomes more costly to cover the next community, while the benefit of covering that community might decline. However, prior to implementation, country-specific analyses would be required to determine for which subset of countries it would be more cost-effective to scale up to higher coverage levels even if it means that some countries are excluded from implementation altogether. The current study also was not designed to consider how programme costs and effectiveness might vary according to whether a more vertical or more integrated approach is adopted, or depending on the level of prior scale of existing diarrhoeal disease, malaria or HIV programmes. These important programme design considerations will depend on the organisation of the healthcare system in each of the countries considering an IPC programme.

Since we looked at a large number of countries, we could not explore specific countries in detail. It was infeasible to develop cost-effectiveness thresholds that reflected the full array of local public health options against which IPC could be considered. Comparing IPC with the estimated cost-effectiveness of ART for HIV does not account for the potential intervention options that are more efficient than both IPC and ART. In addition, there may be substantial regions or urban areas within countries that have costs, health benefits that depart from the overall country assessments to which our analysis is confined. Finally, we were not able to evaluate the cost to patients of seeking care and were thus unable to adopt a full societal perspective. Since disease prevention averts the need for these expenditures, our results may underestimate net costs and thus cost-effectiveness. The current analysis should not displace investigation of potential opportunities for efficient IPC implementation in high disease burden areas within countries.

This study increases confidence that IPC can be an important new approach for enhancing global health. IPC appears to be cost-effective compared to ART for HIV in many settings, and has the potential to substantially reduce the burden of disease in poor countries. If implemented with 15% population coverage in the top 40 of the 70 countries as ordered by cost-effectiveness, 47.3 million DALYs could be averted at a net cost of US$4.9 billion, or US$104 per DALY averted. The specific countries, or number of countries, a donor may want to fund will depend on resource availability, and this analysis provides substantial guidance to decision makers aiming to predict the costs and benefits of various levels of investments in IPC programmes. If taken to scale, IPC can be a highly efficient strategy for improving global health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EM conceived and designed the study, conducted the analyses and drafted and revised the paper. AJ provided data for the study, helped with the analyses and drafting and revision. AR provided data for the study and revised the draft paper. SV and JW critiqued the analysis helped with specifying data inputs, and revised the draft paper. JGK helped guide design and implementation of the study, helped with specifying data inputs and edited the paper.

Funding: Vestegaard Frandsen.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.De Maeseneer J, van Weel C, Egilman D, et al. Strengthening primary care: addressing the disparity between vertical and horizontal investment. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:3–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady MA, Hooper PJ, Ottesen EA. Projected benefits from integrating NTD programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Trends Parasitol 2006;22:285–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linehan M, Hanson C, Weaver A, et al. Integrated implementation of programs targeting neglected tropical diseases through preventive chemotherapy: proving the feasibility at national scale. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;84:5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desormeaux J, Johnson MP, Coberly JS, et al. Widespread HIV counseling and testing linked to a community-based tuberculosis control program in a high-risk population. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 1996;30:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugada E, Millar D, Haskew J, et al. Rapid implementation of an integrated large-scale HIV counseling and testing, malaria, and diarrhea prevention campaign in rural Kenya. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn JG, Harris B, Mermin JH, et al. Cost of community integrated prevention campaign for malaria, HIV, and diarrhea in rural Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn JG, Muraguri N, Harris B, et al. Integrated HIV testing, malaria, and diarrhea prevention campaign in Kenya: modeled health impact and cost-effectiveness. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e31316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiwani A, Matheson A, Kahn JG, et al. Integrated disease prevention campaigns: assessing country opportunity for implementation via an index approach. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The World Bank. How we classify countries 2012. [cited 4 Sep 2012]. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications

- 11.World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 65/1. Keeping the promise: united to achieve the Millenium Development Goals, 2010

- 13.Central Intelligence Agency. Country comparison: GDP per capita (PPP), 2012

- 14.Mbonye AK. Prevalence of childhood illnesses and care-seeking practices in rural Uganda. Sci World J 2003;3:721–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetzel MW, Obrist B, Lengeler C, et al. Obstacles to prompt and effective malaria treatment lead to low community-coverage in two rural districts of Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2008;8:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alba S, Dillip A, Hetzel MW, et al. Improvements in access to malaria treatment in Tanzania following community, retail sector and health facility interventions—a user perspective. Malar J 2010;9:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das A, Ravindran TS. Factors affecting treatment-seeking for febrile illness in a malaria endemic block in Boudh district, Orissa, India: policy implications for malaria control. Malar J 2010;9:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith LA, Bruce J, Gueye L, et al. From fever to anti-malarial: the treatment-seeking process in rural Senegal. Malar J 2010;9:333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littrell M, Gatakaa H, Evance I, et al. Monitoring fever treatment behaviour and equitable access to effective medicines in the context of initiatives to improve ACT access: baseline results and implications for programming in six African countries. Malar J 2011;10:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICF International. STATcompiler—% of children under 5 with diarrhea in 2 wks preceding survey who received any kind of treatment: Measure DHS, 2012

- 21.UNAIDS. Sub-Saharan Africa, Regional fact sheet 2012

- 22.Galarraga O, Wirtz VJ, Figueroa-Lara A, et al. Unit costs for delivery of antiretroviral treatment and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a systematic review for low- and middle-income countries. Pharmaco Econ 2011;29:579–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitajima T, Kobayashi Y, Chaipah W, et al. Costs of medical services for patients with HIV/AIDS in Khon Kaen, Thailand. AIDS 2003;17:2375–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menzies NA, Berruti AA, Berzon R, et al. The cost of providing comprehensive HIV treatment in PEPFAR-supported programs. AIDS 2011;25:1753–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marseille E, Kahn JG, Pitter C, et al. The cost effectiveness of home-based provision of antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2009;7:229–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051993. Marseille E, Giganti MJ, Mwango A, et al. Taking ART to scale: determinants of the cost and cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in 45 clinical sites in Zambia. PloS one 2012;7:e51993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hounton SH, Akonde A, Zannou DM, et al. Costing universal access of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Benin. AIDS Care 2008;20:582–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bikilla AD, Jerene D, Robberstad B, et al. Cost estimates of HIV care and treatment with and without anti-retroviral therapy at Arba Minch Hospital in southern Ethiopia. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2009;7:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig SP, Riviere C, Leger P, et al. The cost of antiretroviral therapy in Haiti. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2008;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet 2009;374:2080–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta I, Trivedi M, Kandamuthan S. Recurrent costs of India's free ART program, in HIV and AIDS in South Asia: an economic development risk. In: Haacker M, Claeson M, eds Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009:244 [Google Scholar]

- 32.John KR, Rajagopalan N, Madhuri KV. Brief communication: economic comparison of opportunistic infection management with antiretroviral treatment in people living with HIV/AIDS presenting at an NGO clinic in Bangalore, India. MedGenMed 2006;8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kombe G, Smith O, Nwagbara C. Scaling up antiretroviral treatment in the public sector in Nigeria: a comprehensive analysis of resource requirements: report issued by PHRplus and Abt associates, 2004

- 34.Aracena-Genao B, Navarro JO, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, et al. Costs and benefits of HAART for patients with HIV in a public hospital in Mexico. AIDS 2008;22(Suppl 1):S141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bautista-Arredondo S, Dmytraczenko T, Kombe G, et al. Costing of scaling up HIV/AIDS treatment in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2008;50(Suppl 4):S437–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleary SM, McIntyre D, Boulle AM. The cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa—a primary data analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinson N, Mohapi L, Bakos D, et al. Costs of providing care for HIV-infected adults in an urban HIV clinic in Soweto, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:327–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen S, Long L, Sanne I. The outcomes and outpatient costs of different models of antiretroviral treatment delivery in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:1005–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deghaye N, Pawinski RA, Desmond C. Financial and economic costs of scaling up the provision of HAART to HIV-infected health care workers in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J 2006;96:140–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harling G, Wood R. The evolving cost of HIV in South Africa: changes in health care cost with duration on antiretroviral therapy for public sector patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;45:348–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kevany S, Meintjes G, Rebe K, et al. Clinical and financial burdens of secondary level care in a public sector antiretroviral roll-out setting (G. F. Jooste Hospital). S Afr Med J 2009;99:320–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gapminder. Data in Gapminder World. Estimated HIV prevalence % (ages 15–49)

- 43.US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index—All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Washington, DC, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 44.The World Bank. How we classify countries, 2012

- 45.Ethiopia Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office. Country Progress Report on HIV/AIDS Response: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2012

- 46.Republique Democratique Du Congo—Programme National Multisectoriel de Lutte Contre le Sida (PNMLS). Rapport d'Activite Sure la Riposte au VIH/SIDA en R.D.Congo 2012

- 47.Cibulskis RE, Aregawi M, Williams R, et al. Worldwide incidence of malaria in 2009: estimates, time trends, and a critique of methods. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The World Bank. Population, total: the World Bank, 2010

- 49.Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, et al. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. World population prospects, 2010 revision, 2010

- 51.UNICEF. The State of the World's Children 2011. Table 6: demographic indicators: under 5 population (2010), 2011

- 52.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Malaria mortality estimates by country 1980–2010, 2009

- 53.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository. Global burden of disease. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lubell Y, Staedke SG, Greenwood BM, et al. Likely health outcomes for untreated acute febrile illness in the tropics in decision and economic models; a Delphi survey. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The World Bank. World Development Report 1993: investing in Health. 1993

- 56.World Health Statistics 2012. Life tables for WHO Member States. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods, and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, eds Global burden of disease and risk factors. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snow R, Newton C, Craig M, et al. The public health burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Africa: deriving the numbers. Disease control priorities project working paper No. 11. Bethesda, MD: Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamberti LM, Fischer Walker CL, Black RE. Systematic review of diarrhea duration and severity in children and adults in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health 2012;12:276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaiser Family Foundation. The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), 2013

- 61.World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease. Table 1: Estimated total deaths ('000), by cause, sex and WHO Member State, 2008, 2011

- 62.Walensky RP, Wolf LL, Wood R, et al. When to start antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:157–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet 2004;364:1428–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ayieko P, Akumu AO, Griffiths UK, et al. The economic burden of inpatient paediatric care in Kenya: household and provider costs for treatment of pneumonia, malaria and meningitis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2009;7:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;2:CD000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clasen T, Haller L, Walker D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries. J Water Health 2007;5:599–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Denison JA, O'Reilly KR, Schmid GP, et al. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDS Behav 2008;12:363–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weller S, Davis K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;1:CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith DL, Cohen JM, Moonen B, et al. Infectious disease. Solving the Sisyphean problem of malaria in Zanzibar. Science 2011;332:1384–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kahn JG, Marseille E, Auvert B. Cost-effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention in a South African setting. PLoS Med 2006;3:e517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mulligan JA, Yukich J, Hanson K. Costs and effects of the Tanzanian national voucher scheme for insecticide-treated nets. Malar J 2008;7:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kilian A, Byamukama W, Pigeon O, et al. Long-term field performance of a polyester-based long-lasting insecticidal mosquito net in rural Uganda. Malar J 2008;7:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clasen T, Naranjo J, Frauchiger D, et al. Laboratory assessment of a gravity-fed ultrafiltration water treatment device designed for household use in low-income settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009;80:819–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lubell Y, Riewpaiboon A, Dondorp AM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of parenteral artesunate for treating children with severe malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:504–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tate JE, Rheingans RD, O'Reilly CE, et al. Rotavirus disease burden and impact and cost-effectiveness of a rotavirus vaccination program in Kenya. J Infect Dis 2009;200(Suppl 1):S76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shillcutt S, Morel C, Goodman C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of malaria diagnostic methods in sub-Saharan Africa in an era of combination therapy. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:101–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.