Abstract

Clathrin-coated vesicles are vehicles for intracellular trafficking in all nucleated cells, from yeasts to humans. Many studies have demonstrated their essential roles in endocytosis and cellular signalling processes at the plasma membrane. By contrast, very few of their non-endocytic trafficking roles are known, the best characterized being the transport of hydrolases from the Golgi complex to the lysosome. Here we show that clathrin is required for polarity of the basolateral plasma membrane proteins in the epithelial cell line MDCK. Clathrin knockdown depolarized most basolateral proteins, by interfering with their biosynthetic delivery and recycling, but did not affect the polarity of apical proteins. Quantitative live imaging showed that chronic and acute clathrin knockdown selectively slowed down the exit of basolateral proteins from the Golgi complex, and promoted their mis-sorting into apical carrier vesicles. Our results demonstrate a broad requirement for clathrin in basolateral protein trafficking in epithelial cells.

Epithelial cells require a polarized distribution of their plasma membrane (PM) proteins to perform a variety of vectorial functions in absorption and secretion1–3. Generation of polarity requires mechanisms to sort the PM proteins into apical and basolateral domains, separated by tight junctions. Sorting is directed by sorting signals in the PM protein. Basolateral sorting signals are distinct determinants in the cytoplasmic domain; in some cases they resemble tyrosine and dileucine motifs similar to those used at the cell surface for clathrin-mediated receptor endocytosis4–7. An epithelial-specific adaptor, AP1B8,9, localizes to recycling endosomes and mediates biosynthetic and/or post-endocytic sorting of basolateral PM proteins with tyrosine motifs (for example vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G protein (VSVG) and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)) and non-tyrosine motifs (for example transferrin receptor (TfR))10–12. AP1B is a tetrameric adaptor with clathrin-interacting domains in its γ subunit that co-localizes with clathrin-coated vesicles near the Golgi13.

All of the above is compatible with a possible function of clathrin in the biosynthetic sorting and recycling of PM proteins. Indeed, an early cell-fractionation study detected a newly synthesized PM protein in clathrin-coated vesicles14. However, a requirement for clathrin in the biosynthetic route of PM proteins has never been shown. Acute cross-linking experiments failed to detect the involvement of clathrin in recycling of TfR to the PM of non-polarized cells15, although more recent in vitro reconstitution experiments16 and an RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) study17 support the involvement of clathrin in non-polarized PM protein recycling. Here we study the involvement of clathrin in PM protein trafficking in polarized MDCK cells by using RNAi and crosslinking approaches to suppress clathrin expression or function, together with a battery of biochemical and live-imaging trafficking assays. Our experiments demonstrate a fundamental role of clathrin in PM protein transport to the basolateral membrane.

Knockdown of clathrin heavy chain in MDCK cells

In the epithelial cell line MDCK, as in other nucleated cells, clathrin localizes prominently to the Golgi region (Fig. 1a). Treatment of MDCK cells with two consecutive cycles (three days each) of siRNA against clathrin heavy chain (CHC) drastically decreased clathrin immunofluorescence in both perinuclear and PM pools (Fig. 1a). The Golgi apparatus had an overall normal shape and localization in clathrin-depleted cells. Western blot analysis (Fig. 1b) showed that the treatment depleted CHC (more than 90%) and clathrin light chains (CLCb, 45%; CLCa, 72%), the latter as a result of decreased stability on depletion of CHC, relative to control MDCK cells treated with siRNA against luciferase, as shown previously in non-polarized cells18,19. Clathrin-depleted MDCK cells grew more slowly than control cells (not shown), as reported previously for fibroblastic cells20. Clathrin depletion slowed the exit of the lysosomal hydrolase cathepsin D from the trans-Golgi network (TGN), as indicated by a delay in the processing of its TGN precursor procathepsin D (51 kDa) to endosomal (48 kDa) and lysosomal (34 kDa) forms of the enzyme21 (Fig. 1c, d). Thus, clathrin depletion by siRNA was effective in abrogating the best-known non-endocytic trafficking function of clathrin, namely lysosomal hydrolase transport, in MDCK cells.

Figure 1. Clathrin knockdown in MDCK cells.

MDCK cells were electroporated twice with CHC or luciferase (LF) siRNAs and used three days later. a, Confocal fluorescence microscopy of monolayers stained with CHC antibody TD1 and Golgi marker giantin. CHC siRNA caused drastic depletion of perinuclear and PM clathrin pools (green); the Golgi complex (red) appeared slightly swollen but normal overall. Scale bar, 10 μm. b, Western blot of cells treated with CHC siRNA, demonstrating strong depletion of CHC (90%), CLCa (72%) and CLCb (45%). β-COP, β-coat protein. c, Impairment of maturation of procathepsin D into lower-molecular-weight forms by clathrin depletion (arrows, arrowheads). Pulse–chase and SDS–PAGE. d, Maturation of cathepsin D quantified by normalizing mature cathepsin D levels at t =4 h over procathepsin D levels at t =0. Mean and s.e.m. are shown (P <0.005, n =3).

The development of epithelial polarity and most of our polarity assays depend crucially on the assembly of functional tight junctions and adherent junctions, which separate apical and basolateral PM domains2,22. Clathrin depletion did not prevent the formation of functional tight junctions. After three days of plating the cells at confluence, the transepithelial electrical resistance reached similar levels, about 100 Ω cm2, in both control and clathrin-depleted cells (Fig. 2a). The [3H]inulin flux across the monolayer was similar in control and clathrin-depleted cells (Fig. 2b). Tight junctions had a normal morphology in clathrin-depleted cells, as determined by immunostaining of the tight-junction marker ZO1 (Fig. 2c). Par6, a polarity protein that localizes at tight junctions23, was also found in its normal localization in clathrin-depleted cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). These experiments showed that clathrin-depleted MDCK cells develop normal tight junctions after three days at confluence.

Figure 2. Clathrin-depleted cells develop normal tight junctions.

a, Development of normal transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) in MDCK cells treated with luciferase (LF) or CHC siRNAs, after three days at confluence. Means and s.e.m. are shown (P =0.45, n =5). b, Normal permeability to [3H]inulin in clathrin-depleted MDCK cells. Means ± s.e.m. are shown for two experiments, with n =3 for each experiment. c, Morphologically normal tight junctions in clathrin-depleted cells. Immunofluorescence with ZO1 antibody. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Clathrin siRNA disrupts basolateral PM polarity

Next we studied the effect of clathrin depletion on the steady-state surface polarity of apical and basolateral PM markers in MDCK cells in control and clathrin-depleted MDCK cells that had been confluent for at least three days. Confocal microscopy (Fig. 3a) and domain-selective biotinylation (Fig. 3b) demonstrated a loss of polarity of most (five out of six) basolateral PM proteins tested, covering a broad range of basolateral signals. These include TfR (tyrosine-independent signal24); VSVG (tyrosine signal25); E-cadherin (dileucine motif26); neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM; tyrosine-independent signal27) and CD147 (single leucine plus acidic cluster signal28). The polarity of Na+, K+-ATPase was not significantly affected, possibly reflecting a clathrin-independent sorting mechanism or its stabilization at the lateral PM by the ankyrin cytoskeleton29. The polarity of the apical PM markers gp135 (ref. 30) (Fig. 3a, b) and p75 (ref. 31) (Supplementary Fig. 2) was not affected by clathrin depletion.

Figure 3. Clathrin knockdown depolarizes basolateral proteins at steady state.

a, Confocal microscopy of control and clathrin-depleted cells. b, Domain-selective biotinylation of control and clathrin-depleted cells. MDCK cells were confluent on filters for at least three days after treatment with luciferase (LF) or CHC siRNAs. Some markers were endogenous (TfR (b), E-cadherin, Na+, K+-ATPase β subunit (ATPase) and gp135). NCAM and CD147 were permanently transfected. VSVG and human TfR (a) were expressed by adenoviral infection. Bl, basolateral; Ap, apical.

Clathrin-depleted cells overexpressed basolateral PM proteins, which is consistent with clathrin’s role in promoting trafficking of PM proteins to the degradative pathway32. However, quantification of the polarity of NCAM tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in individual cells over a broad range of expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 3) showed that the disruption of its basolateral polarity could not be attributed to saturation of the basolateral sorting machinery5.

Clathrin depletion disrupted the recycling of TfR and LDLR from recycling endosomes to the basolateral membrane, as expected from the involvement of AP1B in this route10,12, and promoted the incorporation of both receptors into the apical recycling (transcytotic) route (Fig. 4a). Pulse–chase surface capture assays11,28 demonstrated a large delay in the delivery of newly synthesized TfR, VSVG and CD147 to the basolateral PM and mis-sorting of the proteins to the apical PM (Fig. 4b). These experiments showed that clathrin depletion causes a specific defect in the transport and sorting of basolateral PM proteins in the biosynthetic and recycling routes.

Figure 4. Clathrin knockdown depolarizes surface delivery of basolateral proteins.

a, Clathrin depletion decreases recycling accuracy of basolateral PM proteins. MDCK-cell monolayers on transwells expressing human TfR or LDLR fused to α-bungarotoxin (BTX) binding site (see Methods) were incubated for 2 h in the presence of 125I-transferrin (Tf) (added basolaterally) or 125I-BTX (added to both sides). Basolaterally released or apically released (transcytosed) 125I-Tf was plotted as a fraction of the total endocytosed pool. Basolaterally or apically released 125I-BTX was plotted as a fraction of the total endocytosed pool. Bl, basolateral; Ap, apical. Means ± s.e.m. are shown. b, Clathrin depletion causes retention and promotes depolarized delivery of newly synthesized basolateral PM proteins. TfR and VSVG were introduced by means of adenoviruses, whereas CD147 was permanently expressed. Cells were radiolabelled for 15 min and chased for different durations. Surface delivery of TfR at each time point is plotted as a percentage of total surface delivery at t =75 min. Surface delivery of CD147 and VSVG is plotted as a percentage of total radioactively pulsed protein.

Clathrin depletion slows Golgi exit of basolateral proteins

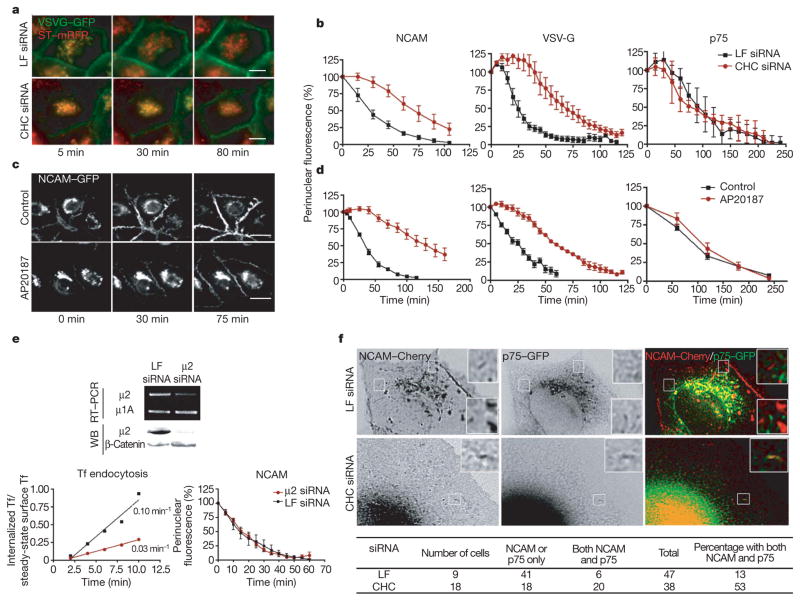

Sorting of PM proteins in epithelial cells takes place at a Golgi or post-Golgi level (see above). To determine whether clathrin knockdown disrupted the trafficking of PM proteins at the Golgi complex, we introduced GFP-tagged basolateral (VSVG–GFP and NCAM–GFP) or apical (p75–GFP) PM proteins by adenovirus transduction (VSVG) or nuclear microinjection of their complementary DNAs (NCAM or p75) into subconfluent MDCK cells, promoted their accumulation at the TGN by incubation for 1–2 h at 20 °C, and then recorded, by live imaging, their exit from the TGN after transfer to 32 °C (refs 31, 33) (Fig. 5a–d). For VSVG–GFP, we used an MDCK cell line permanently expressing sialyl transferase tagged with monomeric red fluorescent protein (ST–RFP) to identify the position of the TGN and quantify the TGN-associated GFP (Fig. 5a). Clathrin knockdown markedly decreased the exit kinetics of both basolateral PM proteins, VSVG–GFP and NCAM–GFP (t1/2 increased from 20–25 min to 70–75 min) but not the exit kinetics of apical PM protein p75 (Fig. 5b, right panel). VSVG–GFP remained strictly co-localized with ST–RFP in clathrin-depleted cells, suggesting that the transport block was at the TGN.

Figure 5. Clathrin suppression disrupts exit and sorting of basolateral proteins at the TGN.

a, Clathrin depletion by siRNA inhibits the exit of VSVG–GFP from the TGN. Experiments were performed in subconfluent MDCK cells expressing ST–RFP after a shift from 20 °C to 32 °C. b, Quantification of the exit of NCAM–GFP, VSVG–GFP and p75–GFP in control and clathrin-depleted cells. Perinuclear GFP was quantified as a fraction of the total cell GFP. Means ± s.e.m. are shown (n >10; two experiments per condition). Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Clathrin crosslinking in MDCK cells expressing clathrin light chain linked to FKBP and haemagglutinin (HA). NCAM–GFP accumulated in the TGN after a 20 °C block moved to PM in control cells, but was blocked at the Golgi in cells treated with crosslinker AP20187 (see also Supplementary Movie 1). d, The exit of NCAM–GFP, VSVG–GFP and p75–GFP from the TGN was quantified from live recordings of MDCK cells expressing HA–FKBP-CLC, in the presence or absence of crosslinker. Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. (n >10 with at least two experiments per condition). e, Inhibition of endocytosis by AP2 knockdown does not delay the exit of NCAM–GFP from the TGN. Treatment of MDCK cells with μ2 siRNA reduced the Tf internalization rate by about 70% compared with control siRNA (0.047 ± 0.015 min−1 versus 0.137 ± 0.019 min−1, n =4) but did not affect NCAM–GFP exit from the TGN, quantified as in b and d. Means ± s.e.m. are shown. WB, western blot. f, Clathrin depletion promotes incorporation of basolateral protein into apical carriers. Cells were co-microinjected with cDNA encoding NCAM–Cherry (basolateral cargo) and p75–GFP (apical cargo). Post-Golgi carriers for p75–GFP, identified by their characteristic speed, contained NCAM–Cherry more often in clathrin-depleted cells than in control cells (represented in the boxed areas). See also Supplementary Movies 2 and 3.

In yeast, knockdown of the CHC gene may be compensated for by the overexpression of a variety of genes34, illustrating the marked ability of cells to develop compensatory mechanisms. We wished to test whether the apparent resistance of apical PM protein sorting to chronic clathrin depletion in MDCK cells might be due to selective compensation of clathrin function by mechanisms only available to apical proteins. To this end, we studied the effect of acutely blocking clathrin function on the exit of PM proteins from the TGN, by using a clathrin crosslinking approach previously shown to inhibit clathrin-mediated receptor endocytosis of TfR in non-polarized cells15. In brief, we generated an MDCK cell line in which CLC tagged with FK-506 binding protein (FKBP) and a haemagglutinin antigen (F-LC) replaced most of endogenous CLC (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Immunofluorescence showed that F-LC co-localized with CHC (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Addition of the membrane-permeant crosslinker of FKBP, AP20187, at 100 nM resulted in maximum clathrin clustering, as reported by a fluorescence titration assay (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). Acute clathrin crosslinking did not cause a delay in the exit of apical protein p75 but caused a selective delay in the exit of basolateral proteins from the TGN, exactly as observed with chronic clathrin depletion by means of siRNA (Fig. 5c, d). Supplementary Movie 1 documents the delayed exit of NCAM–GFP in clathrin-crosslinked cells. Thus, these clathrin knockdown experiments show that clathrin is selectively required for the exit of newly synthesized basolateral PM proteins with tyrosine-dependent (VSVG25) and tyrosine-independent (NCAM27) sorting signals from the TGN, but not for the exit of an apical PM protein, p75 (refs 31, 33).

Basolateral proteins are mis-sorted into apical vesicles

The inhibitory effect of clathrin depletion on the exit of basolateral PM proteins from the Golgi apparatus could be explained by an indirect effect of the block of endocytosis and/or by the incorporation of the PM proteins into apical carrier vesicles that leave the Golgi complex with slower kinetics. To test the first hypothesis, we knocked down the PM clathrin adaptor AP2 in MDCK cells and conducted Golgi exit experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 5a–d. AP2 knockdown drastically inhibited the PM uptake of TfR but did not affect the exit of the basolateral marker NCAM–GFP from the TGN (Fig. 5e). These experiments showed that the inhibitory effect of clathrin depletion at the Golgi is not a result of inhibited endocytosis at the PM. To test the second hypothesis, we performed high-resolution live imaging experiments. These experiments showed that clathrin depletion promoted the incorporation of NCAM–Cherry into apical carrier vesicles containing the apical marker p75–GFP (53% of these vesicles showed the presence of NCAM–Cherry, in contrast with 13% in control cells) (Fig. 5f). Because p75–GFP leaves the Golgi complex with slower kinetics than that of NCAM (see Figs 1 and 2), our experiments show that clathrin depletion causes mis-sorting of basolateral proteins into a slower Golgi exit route normally used by apical proteins.

Clathrin is required for basolateral protein sorting

We have demonstrated a broad and selective requirement for clathrin in the biosynthetic sorting of basolateral PM proteins in epithelial cells. Accurate biosynthetic sorting is probably the main determinant of the polarity of basolateral PM proteins that are endocytosed slowly relative to their recycling rates. Fast endocytic and recycling baso-lateral receptors, such as TfR and LDLR, also require clathrin in their basolateral recycling routes (Fig. 4a), in agreement with their dependence on AP1B for basolateral recycling10,11. These proteins are depolarized to a larger extent by clathrin depletion (Fig. 3), probably as a result of their dependence on this protein in both biosynthetic and recycling routes. The clathrin requirement of TfR in its biosynthetic route (Fig. 4b) is particularly interesting, because this receptor develops an AP1B-independent biosynthetic route in MDCK cells after two days in confluent culture11. Our observation predicts that a clathrin adaptor different from AP1B participates in the biosynthetic sorting of this receptor.

Clathrin-coated vesicles with specificity for different cargoes are produced at the plasma membrane, Golgi apparatus and endosomes through a cooperative process that requires clathrin and about 20 adaptors35–39. Besides AP1B, only one other AP-family adaptor, AP4, has been postulated to participate in basolateral PM protein delivery40, but this adaptor does not seem to interact with clathrin35–37. Our finding that basolateral proteins that do not depend on AP1B for their basolateral polarity, for example CD147 and E-cadherin11,28, require clathrin for their basolateral localization (Fig. 3a, b), also predicts the participation of other clathrin adaptors in basolateral polarity.

METHODS

cDNA constructs and adenoviruses

Plasmids encoding NCAM–GFP, p75–GFP and ST–RFP were described previously41,42. NCAM–Cherry plasmid was generated by subcloning NCAM in pCherry vector into the SalI and KpnI site. pCherry vector was generated by excising GFP from pEGFP-N1 vector with BamH1 and NotI enzymes and replacing it with Cherry. This vector was a gift from A. Müsch. Adenoviruses encoding the human TfR and VSVGtsO45–GFP were provided by I. Mellman and K. Simons, respectively. An MDCK cell line permanently expressing hPar6a–GFP was obtained from A. Müsch.

Antibodies

CHC was detected with the monoclonal antibody X22 (Affinity BioReagents) for immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence experiments, and the monoclonal antibody TD1 (Covance) for immunofluorescence and western blot experiments. Clathrin light chains a and b were detected with the monoclonal antibody CON.1 (Covance). Mouse monoclonal antibody against haemagglutinin (HA) epitope and rabbit polyclonal antibody against giantin were purchased from Covance. Monoclonal antibody against ZO1 was purchased from Chemicon. Monoclonal anti-chicken NCAM antibody (clone 5e) was obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. Monoclonal antibody against the ectodomain of p75 (hybridoma ME 20.4) was provided by M. Chao. Monoclonal antibody against the ectodomain of VSVG (hybridoma 5FαG) was provided by J. Lewis. Monoclonal antibody against E-cadherin was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories. Monoclonal antibody against Na+, K+-ATPase β subunit was purchased from Upstate.

Mouse anti-(human TfR) antibodies were purchased from Zymed (now Invitrogen) and from Chemicon. Goat antibody against human cathepsin D was purchased from R&D Systems. Antibody against β-coat protein was obtained from J. Rothman. Monoclonal antibody against the ectodomain of rat CD147 (RET-PE2 hybridoma) was provided by C. Barnstable. Rabbit anti-GFP antibody and chicken polyclonal anti-μ2 antibody were purchased from Abcam and rabbit anti-β-catenin antibody was purchased from Sigma.

Cathepsin D maturation assay

Cells grown in six-well plates were incubated with methionine-free DMEM for 30 min before labelling. After washes, the cells were pulse labelled with [35S]methionine/cysteine in methionine/cysteine-free DMEM and then chased with normal DMEM supplemented with 5 mM methio-nine and 1 mM cysteine for different periods. After the chase, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed. Cathepsin D was immunoprecipitated with a goat anti-(human cathepsin D) antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analysed by SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography. The band intensities were quantified with a phosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Unidirectional flux of inulin

Inulin permeability was measured by incubating cell monolayers in the presence of 0.5 μCi of [3H]inulin in the apical chamber. At various times, 50-μl aliquots of basal medium were withdrawn and radioactivity was measured with a Wallac Beta Counter (Perkin Elmer). Flux of [3H]inulin into the basal well was calculated as the percentage of total radioactivity administered into the apical well.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Three-day-old filter-grown monolayers of MDCK cells were fixed for 15–20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence by using primary and secondary antibodies tagged with Alexa568 or Alexa-488. Monolayers were stained intact (NCAM, VSVG, p75, CD147) or after permeabilization with 0.075% saponin (E-cadherin, clathrin X22, ZO1). Methanol fixation was used to stain the Na+, K+-ATPase β subunit and clathrin (with TD1 antibody). Confocal images were obtained with a laser-scanning confocal microscope TLS SP2 (Leica) with a 63× oil-immersion objective. Images were acquired with laser excitation bands at 488 and 543 nm.

Biotinylation assay to measure steady-state localization of PM proteins

To determine the steady-state surface polarity of PM proteins, MDCK-cell monolayers, confluent on Transwell chambers for three days, were biotinylated with sulpho-NHS-SS-biotin twice for 15 min at 4 °C, either apically or basolaterally. After biotinylation, the filters were excised and the cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% BSA, and protease inhibitors). Biotinylated proteins were then incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads (Pierce) for 1 h. After washing of the beads, the biotinylated proteins were eluted in SDS-containing sample buffer (Laemmli) and analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting with specific antibodies.

Biotin targeting assays

Quantification of polarized delivery of TfR to apical and basolateral surfaces of MDCK cells was performed as described previously11. MDCK cells confluent on filters for two days were infected with adenovirus encoding human TfR for 28–32 h and were subsequently pulse-labelled for 13 min with 0.5 mCi ml−1 [35S]methionine/cysteine. The excess radioactivity was quickly rinsed off with serum-free DMEM supplemented with 3 mM unlabelled methionine and cysteine. Cells were then chased for the indicated times at 37 °C with serum-free DMEM supplemented with 50 mg ml−1 biotinylated human transferrin (B-Tf) added to either the apical or basolateral sides. At the end of the chase period, excess B-Tf was removed by three consecutive rinses with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 0.5% BSA. The cells were then lysed for 30 min at 4 °C in TfR lysis buffer (TfR-LB/5.5) containing 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM KCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1.5% Triton-X100 and 1% albumin in 40 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 5.5 and supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail that included 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 15 μg ml−1 leupeptin/pepstatin/antipain and 75 μg ml−1 benzamidine-ClH. The B-Tf–TfR complex was then retrieved from the lysate with avidin-Sepharose, boiled in Laemmli sample buffer and resolved on 9% SDS–PAGE. The roughly 90-kDa band corresponding to TfR was detected by phosphorImager and quantified.

To examine the polarized delivery of VSVG to the cell surface, MDCK cells grown for three days on Transwell chambers were infected with adenovirus encoding VSVGtsO45–GFP. After 24 h, the monolayers were pulse-labelled for 15 min with 0.5 mCi ml−1 [35S]methionine/cysteine. At various chase times, filters were chilled to 4 °C and biotinylated from the apical or basolateral sides; the lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies against VSVG protein. Samples were subsequently re-precipitated with streptavidin-agarose, and the biotin-labelled immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS–PAGE, revealed with a phosphorImager and quantified. For CD147 we used a cell line expressing CD147–GFP, and immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-GFP antibody.

125I-Tf internalization assay

One day before the experiment, MDCK cells were infected with adenovirus encoding human TfR. MDCK cells were incubated for 2, 4, 6, 8 or 10 min with 5 μg ml−1 125I-labelled human Tf at 37 °C. After incubation, cells were placed on ice, washed twice with cold neutral pH buffer (Ca/Mg HBSS buffer; Gemini) and incubated for 5 min at 4 °C in pH 2 buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M acetic acid pH 2) to remove surface Tf. After a quick wash with neutral pH buffer, the cells were solubilized and radioactivity was measured. A parallel plate was incubated for 2 h in neutral pH buffer with 5 μg ml−1 125I-labelled human Tf at 4 °C to determine the total surface amount of receptors. The cells were washed six times with neutral pH buffer and solubilized (1% Triton X-100, 0.1 M NaOH), and radioactivity was measured with a Wallac Gamma Counter (Perkin Elmer). Non-specific binding was measured in the presence of a 200-fold excess of unlabelled human Tf and subtracted. The slope of a plot of the ratio of internal human Tf to surface human Tf (4 °C binding) against time was used to measure the internalization time constant.

Recycling of TfR and LDLR

Recycling of TfR was measured with 125I-labelled human Tf (125I-Tf) as a ligand in MDCK cells transduced with an adenovirus encoding human TfR, as described previously11. For these experiments, MDCK cells confluent on Transwell filters for four days were exposed to 125I-Tf from the basolateral side for 2 h, washed at low pH to remove surface 125I-Tf and incubated for different durations at 37 °C in the presence of unlabelled Tf and desferroxamine to follow the release of 125I-Tf into basal medium (basolateral recycling) and apical medium (transcytosis). Recycling of LDLR was studied in MDCK cells permanently expressing BBS-LDLR (α-bungarotoxin (BTX) binding site fused to LDLR), a fusion protein in which part of the luminal domain of human LDLR was replaced by a peptide-binding sequence for bungarotoxin (BBS), thus allowing the use of 125I-BTX as a high-affinity ligand. Cells confluent on filters for four days were incubated for 3 h with 5 μCi ml−1 (0.29 μg ml−1) [125I]Tyr54-BTX (PerkinElmer) at 37 °C to achieve steady-state occupancy of the tagged LDL receptors. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold Hanks buffer with calcium and magnesium. The surface pool of 125I-BTX bound to the BBS-LDLR was cleaved off with 25 μg ml−1 trypsin in Hanks buffer at 4 °C for 30 min. After being washed, the filters were placed at 37 °C in the presence of 25 μg ml−1 trypsin added apically and basolaterally. The medium was collected at 7, 15, 27, 42, 60, 80 or 100 min from apical and basolateral chambers, and radioactivity was measured with a Wallac Gamma Counter. Each time point was performed in triplicate.

Microinjection, live imaging of exit from the TGN and quantification of fluorescence

Expression and accumulation in the TGN of p75–GFP and NCAM–GFP were performed as described previously31. MDCK cells grown on glass coverslips were microinjected in their nuclei with 1–20 μg ml−1 cDNA encoding the GFP-tagged proteins, diluted in HKCl injection buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM KCl pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for 1–2 h and at 20 °C with 100 μg ml−1 cycloheximide for accumulation in the TGN. After release of the temperature block by incubation at 32 °C, cells were imaged as described31. Expression of VSVG–GFP was obtained by transduction with an adenovirus encoding VSVGtsO45–GFP 24 h before the experiment. The cells were incubated overnight at 39 °C for synthesis and accumulation of the protein at the endoplasmic reticulum and incubated for 2 h at 20 °C in the presence of 100 μg ml−1 cycloheximide. The Golgi block was released by transfer to 32 °C and perinuclear and total GFP fluorescence were quantified as described31, to assess the exit of NCAM–GFP, p75–GFP or VSVG–GFP from the TGN. Imaging was conducted with a temperature-controlled stage and a TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon) with a 40× (1.04 numerical aperture) objective. Time-lapse movies were acquired with an ORCA II ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics).

For dual-colour movies, cells were co-microinjected with p75–GFP (1 μg ml−1) and NCAM–Cherry (20 μg ml−1). The co-localization analysis of NCAM and p75 exocytic cargoes was performed manually by tracking single-positive and double-positive structures in the acquired time sequences with the use of Metamorph software (Molecular Devices).

Clathrin crosslinking

The fusion protein construct HA–FKBP-LC was prepared from a plasmid encoding GFP–FKBP-LC, obtained from T. Ryan15. The FKBP portion of this construct is modified to specifically bind the crosslinker AP20187 (Ariad Pharmaceuticals; http://www.ariad.com/regulationkits). To fit our experimental design, the GFP tag was replaced by an HA tag. The sequence encoding GFP was removed with NheI and BglII and the sequence encoding HA was added by ligating the following insert phosphorylated at the 5′ end:

5′-CTAGCTCGCCACCATGTACCCATATGACGTCCCCGACTACGCGA-3′

3′-GAGCGGTGGTACATGGGTATACTGCAGGGGCTGATGCGCTCTAG-5′

The resulting plasmid, pHA–FKBP-LC, was stably transfected in MDCK cells with the use of the Amaxa nucleofection technique (Amaxa). MDCK clones were selected after 1–2 weeks of culture in the presence of G418 and assayed for expression of HA–FKBP-LC by immunofluorescence and western blotting with anti-HA and anti-CLC antibodies.

The ideal concentration of crosslinker (AP20187), added for 30–60 min at 37 °C, to obtain maximal clustering of perinuclear clathrin, was titrated using a Metamorph-based assay that involved measuring the intensity of a thresholded region in each cell, with the threshold set at 50% of the total intensity for one condition and then applied to other conditions.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences between samples were determined by a paired two-tailed t-test analysis using Prism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Müsch, T. McGraw and T. Ryan for comments on the manuscript. This work received support from NIH grants to E.R.-B., from the Dyson Foundation and from the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation. E.P. was supported by a fellowship from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer during the initial stages of this work. R.S. was supported by a training predoctoral grant from the NIH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.D. designed research; S.D., E.P., D.G., R.S., S.B.S. and A.D. performed research; S.D. and E.R.-B. analysed data and wrote the paper.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Mostov K, Su T, ter Beest M. Polarized epithelial membrane traffic: conservation and plasticity. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:287–293. doi: 10.1038/ncb0403-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Musch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeaman C, Grindstaff KK, Nelson WJ. New perspectives on mechanisms involved in generating epithelial cell polarity. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:73–98. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer CB, Roth MG. A single amino acid change in the cytoplasmic domain alters the polarized delivery of influenza viral hemagglutin. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:413–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matter K, Hunziker W, Mellman I. Basolateral sorting of LDL receptor in MDCK cells: the cytoplasmic domain contains two tyrosine-dependent targeting determinants. Cell. 1992;71:741–753. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90551-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Bivic A, et al. An internal deletion in the cytoplasmic tail reverses the apical localization of human NGF receptor in transfected MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:607–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunziker W, Fumey C. A di-leucine motif mediates endocytosis and basolateral sorting of macrophage IgG Fc receptors in MDCK cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:2963–2967. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohno H, et al. Mu1B, a novel adaptor medium chain expressed in polarized epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;449:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folsch H, Ohno H, Bonifacino JS, Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan Y, McGraw TE, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial-specific adaptor AP1B mediates post-endocytic recycling to the basolateral membrane. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:605–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravotta D, et al. AP1B sorts basolateral proteins in recycling and biosynthetic routes of MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1564–1569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancino J, et al. Antibody to AP1B adaptor blocks biosynthetic and recycling routes of basolateral proteins at recycling endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4872–4884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folsch H, Pypaert M, Schu P, Mellman I. Distribution and function of AP-1 clathrin adaptor complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:595–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman JE, Fine RE. Coated vesicles transport newly synthesized membrane glycoproteins from endoplasmic reticulum to plasma membrane in two successive stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:780–784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskowitz HS, Heuser J, McGraw TE, Ryan TA. Targeted chemical disruption of clathrin function in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4437–4447. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagano A, Crottet P, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Spiess M. In vitro formation of recycling vesicles from endosomes requires adaptor protein-1/clathrin and is regulated by rab4 and the connector rabaptin-5. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4990–5000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, et al. An ACAP1-containing clathrin coat complex for endocytic recycling. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:453–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinrichsen L, Harborth J, Andrees L, Weber K, Ungewickell EJ. Effect of clathrin heavy chain- and α-adaptin-specific small inhibitory RNAs on endocytic accessory proteins and receptor trafficking in HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45160–45170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motley A, Bright NA, Seaman MN, Robinson MS. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in AP-2-depleted cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:909–918. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royle SJ, Bright NA, Lagnado L. Clathrin is required for the function of the mitotic spindle. Nature. 2005;434:1152–1157. doi: 10.1038/nature03502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iversen TG, Skretting G, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Clathrin-coated pits with long, dynamin-wrapped necks upon expression of a clathrin antisense RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5175–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0534231100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cereijido M, Robbins ES, Dolan WJ, Rotunno CA, Sabatini DD. Polarized monolayers formed by epithelial cells on a permeable and translucent support. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:853–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson W. Adaptation of core mechanisms to generate cell polarity. Nature. 2003;422:766–774. doi: 10.1038/nature01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odorizzi G, Trowbridge IS. Structural requirements for basolateral sorting of the human transferrin receptor in the biosynthetic and endocytic pathways of Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1255–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas DC, Brewer CB, Roth MG. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein contains a dominant cytoplasmic basolateral sorting signal critically dependent upon a tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3313–3320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda KC, et al. A dileucine motif targets E-cadherin to the basolateral cell surface in Madin–Darby canine kidney and LLC-PK1 epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22565–22572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Gall AH, Powell SK, Yeaman CA, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The neural cell adhesion molecule expresses a tyrosine-independent basolateral sorting signal. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4559–4567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deora AA, et al. The basolateral targeting signal of CD147 (EMMPRIN) consists of a single leucine and is not recognized by retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4148–4165. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson WJ, Veshnock PJ. Ankyrin binding to (Na+, K+)ATPase and implications for the organization of membrane domains in polarized cells. Nature. 1987;328:533–536. doi: 10.1038/328533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herzlinger DA, Ojakian GK. Studies on the development and maintenance of epithelial cell surface polarity with monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1777–1787. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreitzer G, Marmorstein A, Okamoto P, Vallee R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Kinesin and dynamin are required for post-Golgi transport of a plasma-membrane protein. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:125–127. doi: 10.1038/35000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raiborg C, Wesche J, Malerod L, Stenmark H. Flat clathrin coats on endosomes mediate degradative protein sorting by scaffolding Hrs in dynamic microdomains. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2414–2424. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreitzer G, et al. Three-dimensional analysis of post-Golgi carrier exocytosis in epithelial cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:126–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemmon SK, Jones EW. Clathrin requirement for normal growth of yeast. Science. 1987;238:504–509. doi: 10.1126/science.3116672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen DJ, Collins BM, Evans PR. Adaptors for clathrin coats: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:153–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirchhausen T. Clathrin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:699–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearse BM, Smith CJ, Owen DJ. Clathrin coat construction in endocytosis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:220–228. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmen T, Honing S, Icking A, Tikkanen R, Hunziker W. AP-4 binds basolateral signals and participates in basolateral sorting in epithelial MDCK cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:154–159. doi: 10.1038/ncb745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deora AA, Diaz F, Schreiner R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Efficient electroporation of DNA and protein into confluent and differentiated epithelial cells in culture. Traffic. 2007;8:1304–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musch A, Cohen D, Kreitzer G, Rodriguez-Boulan E. cdc42 regulates the exit of apical and basolateral proteins from the trans-Golgi network. EMBO J. 2001;20:2171–2179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.